The company that would eventually become Commodore International was formed in 1958 as an importer and assembler of Czechoslovakian portable typewriters for Canada and the northeastern United States. Its founder was a Polish immigrant and Auschwitz survivor named Jack Tramiel. Commodore first made the news as a part of the Atlantic Acceptance scandal of 1965, in which one of Canada’s largest savings and loans suddenly and unexpectedly collapsed. When the corpse was dissected, a rotten core of financial malfeasance, much of it involving its client Commodore, was revealed. It seems that Tramiel had become friends with the head of Atlantic, one C.P. Morgan, and the two had set up some mutually beneficial financial arrangements that were not, alas, so good for Atlantic Acceptance as a whole. Additionally, it appears that Tramiel likely lied under oath and altered documents to try to obscure the trail. (The complicated details of all this are frankly beyond me; Zube dissects it all at greater length on his home page, for those with better financial minds than mine.) The Canadian courts were plainly convinced of Tramiel’s culpability in the whole sorry affair, but ultimately decided they didn’t have enough hard evidence to prosecute him. A financier named Irving Gould rescued Tramiel and his scandal-wracked company from a richly deserved oblivion. Commodore remained alive and Tramiel remained in day-to-day control, but thanks to his controlling investment Gould now had him by the short hairs.

Tramiel and Gould would spend almost two decades locked in an embrace of loathing codependency. Tramiel worked like a demon, seldom taking a day off, fueled more by pride and spite than greed. Working under his famous mantra “Business is War,” he seemed to delight in destroying not only the competition but also suppliers, retailers, and often even his own employees when they lost favor in his eyes. Gould was a more easygoing sort. He put the money Tramiel earned him to good use, maintaining three huge homes in three countries, a private yacht, a private jet, and lots of private girlfriends. His only other big passion was tax law, which he studied with great gusto in devising schemes to keep the tax liability of himself and his company as close to zero as possible. (His biggest coup in that department was his incorporation of Commodore in the Bahamas, even though they had no factories, no employees, and no product for sale there.) Some of his favorite days were those in which Tramiel would come to him needing him to release some capital from his private stash to help him actually, you know, run a proper business, with a growth strategy and research and development and all that sort of thing. Gould would toy with him a bit on those occasions, and sometimes even give him what he wanted. But usually not. Better for Tramiel to pay for it out of his operating budget; Gould needed his pocket money, after all.

Commodore’s business over the next decade changed its focus from the manufacturing of typewriters and mechanical adding machines to a new invention, the electronic calculator, with an occasional sideline in, of all things, office furniture. They also built up an impressive distribution network for their products around the world, particularly in Europe. Indeed, Europe, thanks to well-run semi-independent spinoffs in Britain and West Germany, became the company’s strongest market. Commodore remained a niche player in the U.S. calculator market, but in Europe they became almost a household name. Through it all Commodore’s U.S. operation, the branch that ultimately called the shots and developed the product line, retained an everpresent whiff of the disreputable. One could quickly sense that this company just wasn’t quite respectable, that in most decisions quick and dirty was likely to win out over responsible and ethical. Which is not, I need to carefully emphasize, to cast aspersions on the many fine engineers who worked for Commodore over the years, who often achieved heroic results in spite of management’s shortsightedness or, eventually, outright incompetence.

Tramiel and Commodore stumbled into a key role in both the PC revolution and the videogame revolution. In 1976 the company was, not for the first nor the last time, struggling mightily. Texas Instruments had virtually destroyed their calculator business by introducing machines priced cheaper than Commodore could possibly match. The reason: TI owned its own chip-fabrication plants rather than having to source its chips from other suppliers. It was a matter of vertical integration, as they say in the business world. Desperate for some integration of his own, Tramiel bought a chip company of his own, MOS Technologies. With MOS came a new microprocessor, one that had been causing quite a lot of excitement amongst homebrew microcomputer hackers like Steve Wozniak: the 6502. Commodore also ended up with the creator of the 6502, MOS’s erstwhile head of engineering Chuck Peddle. For his next trick, Peddle was keen to build a computer around his CPU. Tramiel wasn’t so sure about the idea, but reluctantly agreed to let Peddle have a shot. The Commodore PET became the first of the trinity of 1977 to be announced, but the last to actually ship. Tramiel, you see, was having cash-flow problems as usual, and Gould was as usual quite unforthcoming.

The PET wasn’t a bad little machine at all. It wasn’t quite as advanced in some areas as the Apple II, but it was also considerably cheaper. Still, it was hard to articulate just where it fit in the North American market. Hobbyists on a budget favored the TRS-80, easily available from Radio Shack stores all over the country, while those who wanted the very best settled on the more impressive Apple II. Business users, meanwhile, fixated early on the variety of CP/M machines from boutique manufacturers, and later, in the wake of VisiCalc, also started buying Apple IIs. The PET therefore became something of an also-ran in North America in spite of the stir of excitement its first announcement had generated.

Europe, however, was a different story. Neither Apple nor Radio Shack had any proper distribution network there in the beginning. The PET therefore became the first significant microcomputer in Europe. With effectively no competition, Commodore was free to hike its prices in Europe to Apple II levels and beyond. This meant that PETs were most commonly purchased by businesses and installed in offices. Only France, where Apple set up distribution quite early on, remained resistant, while West Germany became a particularly strong market, with the Commodore name accorded respect in business equivalent to what CP/M received in the U.S. And when a PET version of VisiCalc was introduced to Europe in 1980, it caused almost as big a sensation as the Apple II version had the year before in America. Within a year or two, Commodore stopped even seriously trying to sell PETs in North America, but rather shipped most of the output of their U.S. factory to Europe, where they could charge more and where the competition was virtually nonexistent.

In North America Commodore’s role in the early microcomputer and game-console industries was also huge, but mostly behind the scenes, and all centered around the Commodore Semiconductor Group — what had once been MOS Technologies. In an oft-repeated scenario that Dave Haynie has dubbed the “Commodore Curse,” most of the innovative engineers who had created the 6502 fled soon after the Commodore purchase, driven away by Tramiel’s instinct for degradation and his refusal to properly fund their research-and-development efforts. For this reason, MOS, poised at the top of the microcomputer industry for a time, would never even come close to developing a viable successor to the 6502. Nevertheless, Commodore inherited a very advanced chipmaking operation — one of the best in the country in fact. It would take some years for inertia and neglect to break down the house that Peddle and company had built. In the meantime, they delivered the 6502s and variants found not only in the PET but also in the Apple II, the Atari VCS, the Atari 400 and 800, and plenty of other more short-lived systems. They also built many or most of the cartridges on which Atari VCS games shipped. All of which put Commodore in the enviable position of making money every time many of their ostensible competitors built something. Thanks to MOS and Europe, Commodore went from near bankruptcy to multiple stock splits, while Tramiel himself was worth $50 million by 1980. That year he rewarded Peddle, the technical architect of virtually all of this success, with termination and a dubious lawsuit that managed to wrangle away the $3 million in Commodore stock he had earned.

Commodore’s transformation from a business-computer manufacturer and behind-the-scenes industry player to the king of home computing also began in 1980, when Tramiel visited London for a meeting. He saw there for the first time an odd little machine called the Sinclair ZX-80. Peddled by an eccentric English inventor named Clive Sinclair, the ZX-80 was something of a throwback to the earliest U.S.-made microcomputers. It was sold as a semi-assembled kit, and, with just 1 K of memory and a display system so primitive that the screen went blank every time you typed on the keyboard, pretty much the bare-minimum machine that could still meet some reasonable definition of “computer.” For British enthusiasts, however, it was revelatory. Previously the only microcomputers for sale in Britain had been the Commodore PET line and a few equally business-oriented competitors. These machines cost thousands of pounds, putting them well out of reach of most private individuals in this country where average personal income lagged considerably behind that of the U.S. The ZX-80, though, sold for just under £100. For a generation of would-be hackers who, like the ones who had birthed the microcomputer industry in the U.S. five years before, simply wanted to get their hands on a computer — any computer — it was a dream come true. Sinclair sold 50,000 ZX-80s before coming out with something more refined the next year.

We’ll talk more about Sinclair and his toys in later posts, but for now let’s focus on what the ZX-80 meant to Tramiel. He began to think about a similar low-cost computer for the U.S. consumer market — this idea of a “home computer” that had been frequently discussed but had yet to come to any sort of real fruition. To succeed in the U.S. mass market Commodore would obviously need to put together something more refined than the ZX-80. It would have to be a fully assembled computer that was friendly, easy to use, and that came equipped with all of the hardware needed to hook it right up to the family television. And it would need to be at least a little more capable than the Atari VCS in the games department (to please the kids) and to have BASIC built in (to please the parents, who imagined their children getting a hand up on their future by learning about computers and how to program them).

Luckily, Commodore already had most of the parts they needed just sort of lying around. All the way back in 1977 their own Al Charpentier had designed the Video Interface Chip (the VIC) for a potential game console or arcade machine. It could display 16-color graphics at resolutions of up to 176 X 184, and could also generate up to three simple sounds at one time. Commodore had peddled it around a bit, but it had ended up on the shelf. Now it was dusted off to become the heart of the new computer. Sure, it wasn’t a patch on the Atari 400 and 800’s capabilities, but it was good enough. Commodore joined it up with much of the PET architecture in its most cost-reduced form, including the BASIC they’d bought from Microsoft years before, added a cartridge port, and they had their home computer. After test marketing it in Japan as the VIC-1001, they brought it to North America as the VIC-20 in the spring of 1981, and soon after to Europe. (In the German-speaking countries it was called the VC-20 because of the unfortunate resemblance “VIC” had to the German verb “ficken” — to fuck.) In the U.S. the machine’s first list price was just under $300, in line with Tramiel’s new slogan: “Computers for the masses, not the classes.” Tramiel may have been about the last person in the world you’d expect to start advocating for the proletariat, but business sometimes makes strange bedfellows. Discounting construction kits and the like, the VIC-20 was easily the cheapest “real computer” yet sold in the U.S.

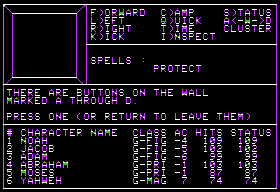

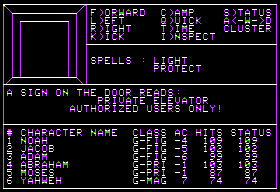

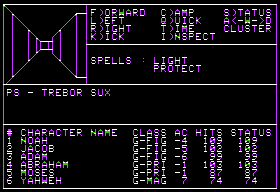

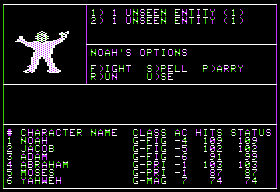

For the first time in the company’s history, Commodore created a major U.S. advertising campaign that was well-funded and smart, perhaps because it was largely the work of an import from Commodore’s much more PR-savvy British subsidiary named Kit Spencer. He hired as spokesman William Shatner, Captain Kirk himself. “Why buy just a videogame?” Shatner asked. “Invest in the wonder computer of the 1980s,” with “a real computer keyboard.” The messaging was masterful. The box copy announced that the VIC-20 was great for “household budgeting, personal improvement, student education, financial planning.” In reality, the VIC-20, with just 5 K of memory and an absurdly blocky 22-characters-per-line text display, was of limited (at best) utility for any of those things. But always Commodore snuck in a reference, seemingly as an afterthought, to the fact that the VIC-20 “plays great games too!” Commodore was effectively colluding with the kids they were really trying to reach, giving them lots of ways to convince Mom and Dad to buy them the cool new game machine they really wanted. Understanding that a good lineup of games was crucial to this strategy, they made sure that upon release a whole library of games, many of them unauthorized knockoffs of current arcade hits, was ready to go. For the more cerebral sorts, they also contracted with Scott Adams to make cartridge versions of his first five adventures available at launch.

Within a few months of the launch, Tramiel made a deal with K-Mart, one of the largest U.S. department-store chains of the time, to sell VIC-20s right from their shelves. This was an unprecedented move. Previously department stores had been the domain of the game consoles; the Atari VCS owed much of its early success to a distribution deal that Atari struck with Sears. Computers, meanwhile, were sold from specialized dealers whose trained employees could offer information, service, and support before and after the sale. Tramiel alienated and all but destroyed Commodore’s dealer network in the U.S., such as it was, by giving preferential treatment to retailers like K-Mart, even indulging in the dubiously legal practice of charging the latter lower prices per unit than he did the loyal dealers who had sometimes been with him for years. Caught up in his drive to make Commodore the home-computer company as well as his general everyday instinct to cause as much chaos and destruction as possible, Tramiel couldn’t have cared less when they complained and dropped their contracts in droves. Eventually this betrayal, like so many others, would come back to haunt Commodore. But for now they were suddenly riding higher than ever.

The VIC-20 resoundingly confirmed at last the mutterings about the potential for a low-cost home computer. It sold 1 million units in barely a year, the first computer of any type to do so. Apple, by comparison, had after five years of steadily building momentum managed to sell about 750,000 Apple IIs by that point, and Radio Shack’s numbers were similar. The VIC-20 would go on to sell 2.5 million units before crashing back to earth almost as quickly as it had ascended; Commodore officially discontinued it in January of 1985, by which time it was generally selling for well under $100. Attractive as its price was, it was ultimately just too limited a machine to have longer legs. Still, and while the vast majority of VIC-20s were used almost exclusively for playing games (at least 98% of the software released for the machine were games), some who didn’t have access to a more advanced machine used it as their gateway to the wonders of computing. Most famously, Linus Torvalds, the Finnish creator of Linux, got his start exploring the innards of the VIC-20 installed in his bedroom. For European hackers like Torvalds, without as many options as the U.S. market afforded, the VIC-20 as well as the cheap Sinclair machines were godsends.

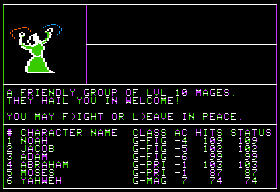

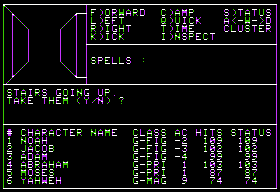

The immediate reaction to the VIC-20 from users of the Apple II and other more advanced machines was generally somewhere between a bemused shrug and a dismissive snort. With its minuscule memory and its software housed on cartridges or cassette tapes, the VIC-20 wasn’t capable of running most of the programs I’ve discussed on this blog, primitive as many of them have been. Even the Scott Adams games were possible only because they were housed on ROM cartridges rather than loaded into the VIC-20’s scant RAM. Games like Wizardry, Ultima, The Wizard and the Princess, or Zork — not to mention productivity game-changers like VisiCalc — were simply impossible here. The VIC-20’s software library, large and (briefly) profitable as it was, was built mostly of simple action games not all that far removed from the typical Atari VCS fare. Companies like On-Line Systems released a VIC-20 title here and there if someone stepped forward with something viable (why throw away easy money?), but mostly stayed with the machines that had brought them this far. To the extent that the VIC-20 was relevant to them at all, it was relevant as a stepping stone — or, if you will, a gateway drug to computing. Hopefully some of those VIC-20 buyers would get intrigued enough that they’d decide to buy a real system some day.

Yet in the long run the VIC-20 was only a proof of concept for the home computer. With the segment now shown to be viable and, indeed, firmly established, the next home computer to come from Commodore wouldn’t be so easy to ignore.

(By far the best, most unvarnished, and most complete history of Commodore is found in Brian Bagnall’s Commodore: A Company on the Edge and its predecessor On the Edge: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Commodore. Both books are in desperate need of a copy editor, making them rather exhausting to read at times, and Bagnall’s insistence on slamming Apple and IBM constantly gets downright annoying. Still, the information and stories are there.

Michael Tomczyk’s much older The Home Computer Wars was previously the only real insider account of Commodore during this period, but it’s of dubious value at best in the wake of Bagnall’s books. Tomczyk inflates his own role in the creation and marketing of the VIC-20 enormously, and insists on painting Tramiel as a sort of social visionary. He’s amazed that Tramiel is willing to do business in Germany after spending time in Auschwitz, seeing this as a sign of the man’s essential nobility and forgiving nature. News flash: unprincipled men seldom put principles — correct or misguided — above the opportunity to make a buck.)