When we left Ken and Roberta they were flush with more money than they’d ever had thanks to the huge success of Mystery House and especially The Wizard and the Princess, and they’d decided to go all-in on a new industry. They pulled up stakes and moved with their two young sons from smoggy Los Angeles to a town of perhaps 1300 called Coarsegold, situated on the periphery of Yosemite National Park, close to the home of Roberta’s parents. They purchased on the outskirts of Coarsegold a wooden mountain cabin connected via a dirt driveway to a twisting mountain road and pronounced it the new “headquarters” of On-Line Systems. It’s about the unlikeliest location imaginable for a major software publisher; neither Coarsegold nor its only slightly less sleepy neighbor Oakhurst had a proper supermarket, restaurant, or even a traffic light when the Williams moved there.

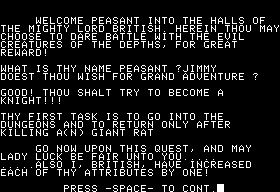

In December of 1980 Ken and Roberta leased their first office space, a 10 foot by 10 foot room above a print shop in Oakhurst’s tiny downtown. They hired Ken’s little brother John as their first official employee to come work with them in it. Some of that work was the sort of thing you might expect. Ken helped Roberta to implement a third entry in the flagship line of “Hi-Res Adventures.” Mission Asteroid, a science-fiction scenario, was numbered Hi-Res Adventure #0 because it was for “beginners”; in other words, its puzzles were somewhat less flagrantly ridiculous than the norm. It hit the market just as the new year began, and turned into yet another solid hit.

Profitable as his and Roberta’s own programming efforts were, however, Ken had bigger ambitions. He saw an industry emerging, and he intended to grab a share of it. On-Line Systems began advertising almost as heavily to game programmers as it did to game players, as Ken worked to put together a stable of programmers to provide more, more, more for the company — more games, more software in general — to feed a rapidly growing microcomputer market that was positively starving for it. These advertisements promoted On-Line Systems as an alternative to the hassles of doing what Ken and Roberta had decided to do, going it alone. From the company’s first newsletter:

Should On-Line Systems market your product we will provide a tech-writer for the documentation, provide all packaging materials, copy protect the software, advertise the product, and help you find any hidden bugs. After you turn over a product to us you do nothing but wait for royalty checks.

Best of all, On-Line Systems offered what it claimed were the “highest royalties in the industry,” 16% of list price, and the chance for “financial independence! No need to ever work anyone else’s hours again…”

Ken also foraged around the trade-show circuit. At the West Coast Computer Faire in April of 1981, he found one of his stars, a gawky 19-year-old named John Harris with a love for Atari’s line of 8-bit machines equaled only by his loathing of all things Apple. (Platform jingoism was an even bigger deal in those days than it is today.) Ken may have had a burgeoning reputation as an Apple II wizard, but he was also a pragmatist. Eager to expand beyond the Apple II market, Ken asked John, “How would you like to program amongst the trees?” A few months later John delivered On-Line Systems’s first big hit on a platform other than the Apple II, Jawbreaker for the Atari 400 and 800. (Jawbreaker will also figure significantly in the story of On-Line Systems for another reason, but we’ll get to that down the road a bit.)

Ken tried to lure the best of his stable of freelancers out to Oakhurst to work for On-Line Systems full-time, even going so far as to purchase houses around the area which he rented out at cost to his programmers, who were often still in their teens, away from home for the first time, and not exactly savvy about basic life skills like negotiating a lease. A snowball effect began. As more money came in each month Ken signed more freelancers and hired more employees, whose work in turn brought in more revenue; only the real epics like Ultima, Zork, or Wizardry generally took more than a single programmer and two or three months in those days. This new revenue allowed him to sign yet more contracts. With the always aggressive Ken pushing hard all the time, On-Line Systems grew rapidly indeed. They absorbed the other offices on their floor one by one, then moved into a brand new building that the owner of the print shop built just for them. Oddly, the company retained Ken and Roberta’s house on Mudge Ranch Road as their official mailing address throughout these changes. The address had become synonymous with On-Line Systems, and in John Williams’s words created a certain image of the company as “a bunch of artisans living up in the woods — kind of a high tech artists commune — and in many ways that wasn’t far from wrong.”

While there were some stereotypically nerdy sorts to be found at On-Line Systems, not least among them the aforementioned John Harris, the company as a whole hewed to the standard set by its garrulous work-hard-play-hard founder Ken. Like any growing company On-Line Systems had to employ plenty of support personnel in addition to the technical staff: secretaries, warehouse workers, couriers, call-center personnel, etc. And anyway, this was the California of the early 1980s, a place where the embers of the hippie era were still being stoked by dedicated diehards who were rather disproportionately represented in the technology sector. There were plenty of parties (many hosted by Ken himself, and held in the On-Line Systems offices), and plenty of drinking and other forms of chemical indulgence. From Steven Levy’s Hackers:

Tuesday night was “Men’s Night,” with Ken out on a drinking excursion. Every Wednesday, most of the staff would take the day off to go skiing at Badger Pass in Yosemite. On Fridays at noon, On-Line would enact a ritual entitled “Breaking Out the Steel.” “Steel” was the clear but potent Steel’s peppermint schnapps which was On-Line Systems’s beverage of choice. In company vernacular, a lot of steel would get you “sledged.”

The townsfolk around them were not always so pleased by such carryings on. John Williams:

Our neighbors in this small town were not always so enthralled with us. We were young in a town of mostly retirees, and we were pretty prosperous in a town of fixed incomes. We drove sports cars not pick-up trucks, and didn’t have “real jobs like real people.” (Someone actually said that to me once.) Amongst the families that did live in town, we were seen as a corrupting influence.

With ever growing numbers of young employees of both sexes and few outside social opportunities, fraternization was not just permitted but the norm. At one point it was determined during a staff meeting that over 50% of the workforce was in a relationship with someone else at the company, a situation that could cause complications when the time came to let someone go. Even those inept in the ways of love were given hope; Hackers records in amusing detail the lengths Ken went to to get the shy and awkward John Harris laid, lengths that included arranging blind dates, taking him on a trip to Club Med, and finally, out of desperation, just paying a stripper to have sex with him already. (None of it — not even paying the stripper — worked). Levy calls this period of On-Line Systems’s history “summer camp,” a time when everyone loved what they were doing on and off the job and when the money just kept rolling in, in ever bigger amounts with each passing month.

At the head of it all, Ken seemed like he had been born for this moment. With the boundless energy and ambition that had always characterized him, he seemed to be involved in everything. In addition to all the day-to-day decisions involved in running a company, he continued to do much of the programming on the Hi-Res Adventure line that remained the company’s biggest moneymakers, while, as one of the most respected Apple II hackers in the industry, also serving as teacher and technical consultant to any and all of his stable of employees and freelancers. When advertising to prospective programmers, On-Line Systems even listed privileged access to Ken as one of its best perks: “I (Ken) will personally be available at any time for technical discussions, helping to debug, brainstorming, etc.”

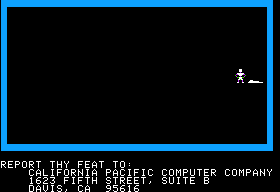

Despite the reservations of the more conservative residents, Ken, head of a company that was becoming a bigger and bigger part of the economies of Coarsegold and Oakhurst, became an increasingly big man about town — soon enough, the big man. Ken threw himself into the role of “town father” with his usual abandon, splashing money liberally around town for causes such as the rebuilding of the needy local fire brigade. He also hired frequently from the local population, partly for the most practical of reasons: personnel like phone operators could be had for a third of what it would have cost in a big city. Still, he also offered ambitious locals the opportunity to build genuine careers for themselves. A boat sander eventually became a vice president in charge of product development; a hotel maid head of the accounting department; a plumber head of product acquisition. Ken hired Bob Davis out of a local liquor store. Soon Bob, a 27-year-old frustrated musician who had spent all of his previous working life as a cook or a cashier, had a Hi-Res Adventure of his own in stores, Ulysses and the Golden Fleece, built using the tools Ken had developed for Roberta’s early efforts.

Yet for all that, Ken made his most significant contributions outside of his own company and outside of the tiny society of Coarsegold and Oakhurst, to the industry at large. In fact, this figure, so known to a whole generation of gamers as the yin to Roberta’s adventure-gaming yang, is paradoxically under-credited for the role he played in shaping the software industry. Amongst the software industry at large, his contribution is perhaps exceeded only by that of Bill Gates, and when we talk about games… well, I’m not sure he has an equal. Faced with an emerging market of well-nigh limitless potential, this die-hard capitalist decided that a rising tide lifts all boats, and did much that aided his competitors as much as it did On-Line Systems.

I’ve already mentioned the most important of these initiatives: the founding of the first true software distributor, which Ken spun off to his friend Robert Leff for just $1300. Without a distribution network to get software easily and efficiently into stores across the country, publishers like On-Line Systems and its competitors could not have thrived as they did; nor, for that matter, could the computer industry as a whole. Distribution was in fact a constant obsession with Ken. During that hectic year of 1981 when he was building his own company from virtually nothing, he also found time to co-found Calsoft with an old colleague from his previous life as a computer consultant, Jay Sullivan. Calsoft was a mail-order software store, the first of its kind. While many early publishers, among them Adventure International and California Pacific, did much of their business via mail order, Calsoft became the first to offer a full selection of software from many different publishers, all sales-tax-free thanks to the peculiarities of interstate commerce in the U.S. and usually generously discounted from typical in-store prices. Calsoft was largely run by Sullivan out of Agoura, California, but On-Line Systems’s phone operators helped with order fulfillment and its art department with the design of the catalog and advertising materials. It was another way of giving buyers, especially those in rural areas or otherwise unable to make it into a brick-and-mortar store, easy access to the products of not only On-Line Systems but also their competitors. Soon the magazines were full of other mail-order firms that sprung up in Calsoft’s wake.

Moves like these were prompted by contrary currents moving through the computer industry in general. VisiCalc, along with other early business applications such as WordStar, had finally managed to establish microcomputers as tools possessed of real, practical usefulness. In general, that was of course a good thing, driving sales of both software and hardware and growing the industry. Problem was, most of the people buying Apple IIs and CP/M machines for their offices were not interested in superficial amusements like playing games or even hacking code. Many, in fact, wanted a machine of serious intent, one that did not want to play; being No Fun was an essential feature. Therefore many dealers, even of the Apple II, the machine that Steve Wozniak had partially designed around the features that would let it play a good game of Breakout, began to shy sharply away from any association with the gaming industry. ComputerLand, the largest computer retail chain and the place where Richard Garriott had begun his career by selling Akalabeth, tried to institute for a time a policy of not stocking games on its shelves. Even Apple themselves were ambivalent about games; they didn’t go out of their way to discourage them, and certainly played plenty of them internally, but preferred to promote the Apple II as a serious tool of business and education. (Ironically, and more foolishly, other manufacturers went in the opposite direction; Atari told companies that proposed developing business applications for its really very impressive computers that these machines were fundamentally “game machines,” and not a suitable market for such products.) Ken felt genuine fear that a new generation of be-suited bandwagon jumpers would succeed in squeezing games off of the Apple II and other machines, relegating them to much less capable game consoles like the Atari 2600. Thus initiatives like Calsoft, to bring his message directly to the people, as it were. He began another project, Softline magazine, for similar reasons.

In an effort to build customer loyalty as well as “build a base of gamers” in general, On-Line Systems had sent its first newsletter to every registered purchaser of their games in June of 1981. However, Ken, feeling far more threatened by those interests that would turn the Apple II into a boring business machine than by his own competitors in the games industry, dreamed of a way of reaching all gamers via a more generalized gaming and “casual computing” magazine. The need for such an organ seemed clear enough to Ken; even traditional hacker’s favorite Byte magazine was starting to focus more and more on business by this point. (I trust I need not belabor the irony of Ken, a guy who had founded On-Line Systems to create a FORTRAN compiler and who had been as dismissive of games as those ComputerLand executives barely a year before, becoming a computer-games evangelist.) Ken had already established a relationship with Margot and Al Tommervik, publishers of the most beloved of the early Apple II magazines, Softalk. Margot in particular was quite enamored with games. Even before founding Softalk, she had come to the attention of the Williams when she won a contest to become the first to solve Mystery House. Once Softalk had begun, Ken had supported it with generous ad buys, and encouraged others in the industry to do the same.

It was to Margot and Al that Ken turned with his idea for a new magazine that would concern itself mostly with games, that hidden driver of computer sales and dirty little secret of countless folks who ostensibly bought their machines for word processing or accounting. He felt the need for such a magazine so intensely that he was willing to underwrite it at a loss; the magazine would be entirely free, with the audacious if forlorn hope that it would at some point become self-sustaining through ad buys. Softline did not openly proclaim its association with On-Line Systems, appearing by all obvious evidence to be a spinoff of Softalk. Yet, and while Margot and Al served as editors and handled most of the day-to-day business, Ken’s fingerprints were everywhere. Ten of the 18 ads in the first issue — dated September 1981 — were from On-Line Systems, while the initial subscription roll consisted of the mailing list to which On-Line had been sending their in-house newsletter. On-Line Systems often penned reviews for the magazine, and Ken himself wrote a series of in-depth articles on graphics programming for the Apple II, the content of which was not too far removed from the lessons he gave inside On-Line Systems. Of course, even by the rather lackadaisical professional standards of modern videogame journalism it would be considered an outrage for a publisher to get so involved financially and editorially with an avowedly independent magazine today. However, as John Williams says: “Like a lot of things we did in the beginning, we did them because they needed to be done and stopped doing them when the industry grew up enough to develop the business.”

As it happened, some of Softline‘s thunder was stolen by another magazine that debuted a couple of months later, Computer Gaming World. CGW had links with wargame publisher Strategic Simulations that went almost as deep as those of Softline to On-Line Systems, leading to a somewhat stodgy publication that had a profound interest in military strategy games and often gave short shrift to just about everything else. Over time, however, its editorial interests broadened, and it went on to become a 25-year institution in gaming. With the success of CGW perhaps signalling that Softline no longer “needed to be done,” On-Line Systems gradually disentangled themselves from Softline, which in late 1982 went to a more traditional paid-subscription model like that of CGW. A couple of years later Softalk and Softline went out of business, but Softline‘s pioneering role should not be forgotten — nor Ken’s having been the one who got it all started.

One remarkable aspect of the early American software industry is how geographically dispersed it was. In 1981, Scott Adams was running Adventure International from a bedroom community near Miami; Muse had established their office and storefront in downtown Baltimore; Infocom was just leasing its first office space and beginning to look like a real company in Boston; Richard Garriott was coding his games from a bedroom in Houston and a dorm room in Austin; the folks working at The Computer Emporium in Des Moines had decided to stop just selling other people’s software and start making some of their own to sell; and from a suburb of Seattle Microsoft were adopting an earlier operating system called 86-DOS to suit the needs of IBM’s new PC, the project that would make the company, make history, and make just about everyone involved millionaires or billionaires. Still, a disproportionate part of the industry was concentrated, as you might expect, in California. In addition to companies we’ve already met — On-Line Systems, Edu-Ware, Automated Simulations, California Pacific, Personal Software — there were also plenty of others, such as Sirius Software, known for its series of fast-action games churned out by resident genius Nasir Gebelli on virtually a monthly basis. With all of his industry-wide initiatives and his outsized personality, Ken became the de facto leader and social guidance counselor of the entire California entertainment-software industry. With the market growing month-by-month, alleged competitors could, at least for the time being, afford to be friends.

Ken and Roberta hosted a Western-themed coming-out party of sorts for On-Line Systems on May 16, 1981, to celebrate the one-year anniversary of Mystery House‘s release. (What a difference a year had made!) Coarsegold and Oakhurst offered only a handful of hotel rooms at the time, so — shades of the California computer industry’s hippie heritage — some guests drove up with camper vans or trailers, while others sacked out on whatever couches Ken could find for them amongst On-Line Systems’s employees. In the photo below, that’s Ken in the center, with Phil Knopp of Sirius Software to his left.

Al Remmers of California Pacific, the man who introduced Lord British and Ultima to the world, came with his wife.

As did plenty of others; Sherwin Steffin of Edu-Ware peeks out from the back right corner of the table in the photo below.

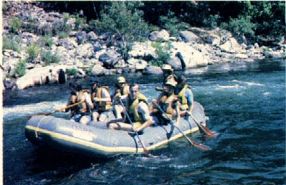

A good time was had by all, and a precedent was set. On-Line Systems’s parties became “must-attend” events for the California industry. That summer Ken’s brother John, On-Line’s marketing director at the tender age of 19, organized a river rafting trip for a big chunk of the industry, among them David Mullich, creator of The Prisoner for Edu-Ware. An article from, naturally, the first issue of Softline describes the results wrought by this combination of water, sun, camaraderie, and of course alcohol:

The party got rowdy near the trip’s end as paddlers prepared for one final brawl. Ken Williams took the last rapid standing up on the front rail of his craft, and Randy Hyde followed suit. With Ken perched on the rail’s edge like a kamikaze waterskier, his crew rammed and boarded the unsuspecting craft, throwing half of the surprised occupants overboard. Bob Christiansen (Quality Software) got a chance to test out his underwater camera when it wound up in the drink with him. Rafters who wound up in the water struggled to pull others overboard, while those still on board fended off the attackers with paddles. Water from paddles and buckets flew over the ten rafts.

Market consultant Diane Ascher was also on the trip, and spoke a bit about how it felt to be alive in this historical moment:

“This is a group of people that is always looking for an excuse to party. The river just provided us with a scenic backdrop. Basically we have a lot in common. We sort of feel like we beat the system: we got to microcomputers before IBM did.”

That last sentence reads as almost chilling today. Summer camp can’t last forever; Big Blue was in fact about to arrive on the scene at last, along with plenty of other new pressures. Most of the companies represented on the trip, so flush with cash and success, would be out of business within a few years.

But we’ll come to that soon enough. For now, let’s enjoy the halcyon days a bit more. Next time: the most controversial computer game of 1981, and one of the most successful.

(My huge thanks to John Williams, whose detailed recollections of these days informed much of this post.)