Bill von Meister’s rude expulsion from The Source didn’t mark the end of his schemes to invent the world’s online future. In 1981, with his erstwhile partner Jack Taub’s $1 million settlement check burning a hole in his pocket, he launched into a plan as visionary as anything he had ever come up with. Almost two decades before Napster would rock the music industry by providing listeners with a convenient application for finding and downloading music online for free, almost a quarter of a century before Apple would legitimize digital music delivery via the iTunes Store, von Meister proposed to create The Home Music Store.

Courtesy of the singing Osmond family, he had secured the use of a satellite-transmitting station near Salt Lake City, Utah. He wanted to use the station to send music to cable-television operators all over the country, who would then send it on to their customers. If they paid a fee, said customers would be allowed to use the cassette recorders that had become so ubiquitous in recent years to make a permanent copy for themselves — a sort of “pay-per-listen” system similar to the pay-per-view systems cable television was already using for big-name boxing matches and other live sporting events.

Von Meister won the tentative support of no less a pillar of the music industry than Warner Bros., and the scheme seemed destined to move forward. But the music industry is, as anyone who has studied its uniformly antagonistic responses to new technologies over the years will attest, an inherently conservative, even reactionary institution. When news of the plan leaked into Billboard magazine, Warner Bros. heard from record stores and record pressing plants alike that The Home Music Store would ruin them. The brick-and-mortar stores promised Warner Bros. a boycott if they continued with the plan. It just wasn’t worth it, the latter decided, especially not when the pivotal figure had as checkered a reputation as Bill von Meister. So, he was duly summoned to a Manhattan high rise to be given the bad news.

Warner Bros. did, however, mention a potential consolation prize. They happened to own Atari, currently the hottest company in consumer electronics. Could von Meister make his delivery system work for Atari VCS games instead of music? If he could prove that he could, they should all talk again. He walked out of the high rise incensed at what he saw as Warner Bros.’s betrayal of his music scheme, but excited about this new bauble they had dangled before him. Such was the life of Bill von Meister.

He formed yet another in his long line of startups in Vienna, Virginia, calling it Control Video Corporation. (Perhaps not inadvertently, the name echoed that of Control Data Corporation, a long-established maker of supercomputers that was making a push into the consumer marketplace at just that time via a big investment in The Source.) Then, with the help of a handful of hand-picked confidantes, he set about refining his new plan to offer downloadable Atari VCS games. The service was to be known as GameLine.

Would-be videogame downloaders would have to purchase, for about $60, a “Master Module” which plugged into the Atari VCS’s cartridge slot. It contained 8 K of volatile memory and a 1600-baud modem. After paying an additional $15 signup fee, customers would be able to download games using the Master Module for $1 apiece. At that price, the subscriber would actually be renting the games for a single session rather than purchasing them; only one game at a time could live in the Master Module’s memory, from whence it could be played only five to ten times before its lease expired. Thus the same subscriber might wind up downloading a game she really liked many times over. For the benefit of skeptical parents, von Meister noted pointedly that playing videogames in the home using his system should be far cheaper than dumping quarters into a standup-arcade machine. He even promised parental controls, allowing parents to set a cap on their children’s weekly usage.

As it happened, Warner Bros., the company that had guided von Meister’s thinking in this direction in the first place, never did come back to the table, nixing any hopes he might have had to make GameLine an official Atari add-on. In compensation, though, lots of venture capitalists who probably ought to have known better by now fell to his sheer passion and charisma — and to the fact that anything to do with videogames was so white-hot among their ranks in the early 1980s.

GameLine made its public bow in typically flamboyant von Meister fashion. For the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January of 1983, he bought an enormous hot-air balloon, which he flew above the Las Vegas Strip with “GAMELINE” written on it in proud capitals. He invited selected show attendees to his suite at the Tropicana Hotel, where there awaited a chorus line of dancing showgirls and a drawing for a one-ounce bar of gold. “It was a lot of schmaltz,” admitted Control Video’s head salesman of the time, but it served the purpose. Everyone thought GameLine a smashing idea. Control Video surfed out of Vegas on a wave of good press, with pre-orders for 150,000 Master Modules from several major retailers. And yet the really significant result of that week in Vegas would only slowly reveal itself over the course of years.

That January of 1983, Steve Case was a 24-year-old marketing manager for Pizza Hut. His older brother, Daniel Case III, worked for Hambrecht & Quist, a Silicon Valley venture-capital firm that had invested majorly in Control Video. Forced by his own job to live in Wichita, Kansas, a place he loathed, Steve Case came to Vegas simply to enjoy the nightlife and to ride his brother’s coattails into places where ordinary members of the public weren’t invited. Among these was Control Video’s private suite at the Tropicana. He was immediately taken with GameLine and with the whirling dervish of charisma that was Bill von Meister, doubly so given that he had recently subscribed to The Source, von Meister’s earlier creation. (“When I finally logged in and found myself linked to people all over the country from this sorry little apartment, it was just exhilarating.”) Desperate to get out of Pizza Hut, where his job as a “marketing manager” largely entailed traveling to pizza shops all over the country and scoring their output on five criteria — the only thing he liked about these trips was that they got him out of Wichita — he asked his big brother for yet another favor.

Shortly after Winter CES, Daniel Case III called Bill von Meister, pointedly touting the merits of his little brother, who would very much like a contract to work with Control Video as a marketing consultant. With millions in actual and potential investments on the line from Hambrecht & Quist, von Meister had little choice but to hire this unknown kid whom he had apparently met but couldn’t actually remember at all.

Indeed, a certain unmemorability had been the curse of Steve Case’s life to date, especially given the shadow cast by his hugely successful older brother. Nothing on his blandly handsome all-American face gave memory any hooks to hang itself on, and nothing of much notability ever seemed to emerge from his mouth either. The product of an affluent family and a privileged upbringing, his record as an undergraduate at Williams College had been undistinguished enough that he hadn’t been accepted by any of the MBA programs to which he had applied, leading him to enter the workforce as a low-level marketing functionary with the dry-goods giant Procter & Gamble. There he’d been assigned to something called Abound, a moist towelette for the hair and scalp; “Towelette, you bet!” had been his best attempt at a tagline. When Abound flopped, he’d wound up at Pizza Hut as a glorified pizza taster.

If you’d told anyone in or around Control Video that one among their ranks was destined to become one of the most prominent online moguls of the 1990s, then asked them exactly who they thought that person was, it seems safe to say that Steve Case wouldn’t have topped anyone’s list. Von Meister took to calling him “Lower Case”; his big brother, whom von Meister judged to be far more critical to Control Video’s success, was of course “Upper Case.” Michael Schrage, the Washington Post‘s technology reporter, would later describe him as “the least quotable human at the company.” If a time traveler from the year 2000 had indeed told him that “Steve Case was chairman of AOL Time Warner,” Schrage would later muse, “you would have to hospitalize me for internal hemorrhaging. Silly beyond belief — Steve Case??”

Slowly, though, this gawky kid that had been foisted on him began to win von Meister’s grudging respect. Still a non-presence in meetings, Case started turning in written reports demonstrating a vision that dovetailed nicely with von Meister’s own, including a strong Machiavellian streak. “Erect barriers to entry (lock up category),” he wrote in one. “Concentrate on the perceptions of the product, not the realities of the product,” he wrote in another. Most of all, he pushed the idea that GameLine could eventually deliver far more than videogames into American homes. The long-term goal should be to “turn your game console into a home computer.” He proposed email, news, and online banking as possible applications; much the same applications, in other words, that were already being tried out on services like CompuServe and The Source. In fact, his ideas hewed very close to von Meister’s original 1979 vision of The Source, since watered down somewhat by various realities, as the “information utility of the future.” The difference was that GameLine’s technology would allow Control Video a measure of — appropriately enough, in light of their name — control over every aspect of the subscriber’s experience.

So, over the course of the spring of 1983 Control Video began to talk about GameLine in a new way. Von Meister, coming full circle back to those heady days of 1979, took to saying that it would “turn today’s video jock into tomorrow’s information genius.” Never a man of small dreams, his plans for GameLine seemed to grow with every telling.

In effect, we are turning those dedicated game units into multi-purpose communications terminals and bringing the benefits of sophisticated computers within the reach of the average household. A videogame console can now be a real teaching machine.

Several videogame manufacturers have announced their intentions to develop add-on equipment which will turn game units into small computers. Our system leaps ahead of those add-ons to tie VCS and compatible units into a national telecommunications network fed by the power of a large central computer’s database.

In keeping with Case’s exhortation to concentrate on perceptions rather than realities — certainly not advice von Meister needed to be given twice — plenty of reasons to wonder how all of this would work in the real world were swept under the carpet. Delivering VCS games via GameLine made a measure of sense in that the Master Module’s internal modem was merely a delivery mechanism for code which then resided locally on the console; estimates were that any extant game, thanks not least to the extreme limitation imposed on a game’s potential size by the architecture of the VCS itself, could be downloaded within one minute. But other forms of information couldn’t, as an executive with potential competitor The Source put it, “be quantified into units as games can.” For that matter, how on earth would you enter text on a “computer” equipped only with a joystick? Control Video’s plan to have the user select letters one by one from an onscreen list certainly didn’t sound like much fun. Trying to build an online service around the Atari VCS felt rather like trying to start a transcontinental airline flying Sopwith Camels.

Other difficult realities dogged even the part of the plan that did sound relatively feasible, the downloadable Atari VCS games. While von Meister had inked deals with an impressive-sounding nine VCS game publishers, conspicuously absent from the list were the two biggest publishers of all, Atari’s own software division and Activision, with the former adopting a wait-and-see attitude, the latter flatly rejecting having anything to do with GameLine under any circumstances. Von Meister tried to persuade reluctant publishers by offering up the idea of GameLine as a sort of try-before-you-buy service that could actually lead to increased sales of their physical cartridges, but his audience was plainly skeptical of the notion. It seemed that Activision in particular, whose games were widely regarded as the best you could buy for the Atari VCS and therefore sold at a premium, thought that their brand could only be diminished by the association. Von Meister hired programmers to create thinly veiled clones of some of the hit games that were unavailable to him, but in doing so he was entering some legally dangerous waters.

Still, all of those issues might conceivably have been overcome; the buzz that would have followed a successful GameLine launch might have convinced even Activision to come around. It was rather the launch date of July 1983 that truly killed any chance Gameline might have had. This was the summer of the Great Videogame Crash, when cracks that had been spreading through the foundation of the House Atari Built for at least a year suddenly brought the whole edifice down around everyone’s heads. Almost overnight, videogames went from being the hottest trend in business to an anathema. Control Video couldn’t have picked a worse instant for GameLine’s launch if they had tried.

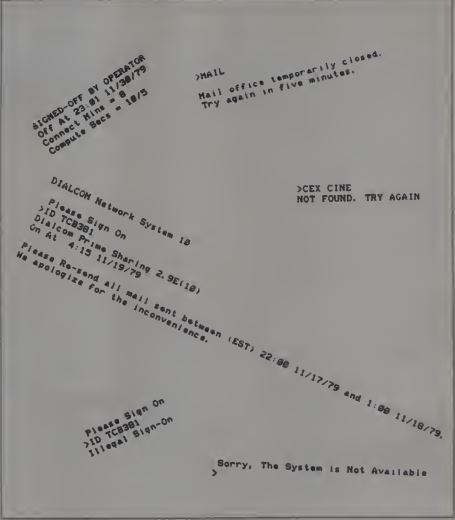

Launch they did, though, trying to make the best of a bad situation. Whatever else you could say about the whole enterprise, the technology that brought it off was a virtuoso hacking feat. It was largely the work of a longtime von Meister compatriot named Mark Seriff, who had previously designed much of the original incarnation of The Source. The video below gives a rare glimpse of his GameLine work in action. Note that Control Video had a policy of offering unlimited free downloads on a subscriber’s birthday, one of a number of canny loyalty-building touches that might have turned the service into a success despite it all if the timing had been a bit better.

But the timing was just far, far too atrocious to be overcome; GameLine never had a chance. By a few months after the launch, it had managed to attract no more than 5000 subscribers, and new signups had fallen to just one or two per day — hardly enough to justify the complicated telecommunications infrastructure into which Control Video had had to invest heavily just to get the service started. In October, they slashed their predicted sales of 250,000 Master Modules by the end of 1983 to 100,000, and it was hard to imagine how they hoped to make even that figure when they had more boxes coming back from retailers than they were shipping out.

The venture capitalists, who had invested some $9 million in Control Video to date, were, to say the least, growing concerned. Von Meister may have been beset by market circumstances that were out of his control, but that didn’t keep them from pointing fingers. They noted wryly that the most profitable single transaction he had managed to date had been to resell the hot-air balloon he had flown over Vegas for $15,000, three times what he had paid for it. The jokes practically wrote themselves: von Meister may not be much good at selling videogames, but he sure can sell hot air. Now, he was telling them he needed another $3 million to execute the pivot from provider of videogames to general-purpose information service well before they had originally planned to make it. It was the only chance they had, he claimed. The venture capitalists couldn’t really disagree, but they did decide to attach some strings to this latest capital injection. Bill von Meister, they decided, needed some adult supervision. Luckily, one of them had an old army buddy who he thought would be just the man for the job.

After graduating from West Point, Jim Kimsey had served two tours of duty in Vietnam as an airborne ranger. Upon returning to civilian life, he became a wealthy man by opening a chain of bars across the Washington Beltway. Like von Meister, he lived fast — one acquaintance remembers him as a “skirt-chasing, hell-raising restaurant owner” — but West Point had instilled a sense of responsibility in his professional life which his peer manifestly lacked. More than anything else, he hated excuses. “If you are a platoon leader, and one of your men dies, there is no excuse,” he once said. “If you are a CEO, and thousands of your employees are laid off, there is no excuse.” His friend picked him for the task of saving Control Video not least because he regarded the very idea of any company with which he was associated going bankrupt as such a personal affront. He knew nothing about computer technology, and didn’t much care to learn, but he knew a lot about whipping any organization, whether a platoon or a corporation, into disciplined fighting trim. Which is not to say that he accepted the role of taskmaster at Control Video with any relish; he took the office next to von Meister’s strictly as a favor to his investor friend, announcing loudly that he was only there for as long as it took to right the ship. He would actually remain for twelve years.

Von Meister couldn’t have been happy about this intrusion on his authority, but if he wanted the venture capitalists’ money he would have to accept Jim Kimsey, just as he had earlier accepted Steve Case. Speaking of whom: one of the first decisions von Meister and Kimsey made together was to elevate Case from his part-time consultant’s gig to that of a full-time marketer. “What do you think about Steve?” von Meister had asked Kimsey. “He seems bright, he won’t cost you much,” the latter had replied. But once again there was an ulterior motive as well: Daniel Case III would be extra committed and extra patient with them all if Control Video became his little brother’s permanent employer.

Von Meister, Kimsey, and Case did their level best to make a success of the pivot from games to information. After all, those 15 million or so Ataris that remained in American homes post-Crash ought to be ripe for re-purposing now. Already in September of 1983, StockLine had gone up alongside GameLine, allowing subscribers to track prices on the New York Stock Exchange, the money markets, currency exchanges, and metal exchanges, and even to store a permanent personal portfolio of up to ten stocks, thanks to a few hundred bytes of non-volatile memory a forward-looking Control Video had quietly stashed away inside the Master Module. Control Video claimed that SportsLine was coming soon with all the latest scores and up-to-the-minute Vegas odds, and that MailLine, featuring email and a real-time chat system like CompuServe’s CB Simulator, would follow thereafter. “We’re not in trouble,” insisted von Meister (like a politician telling people he isn’t a crook, the very fact that he was being forced to make such an insistence was of course proof of the opposite in the minds of his interlocutors from the business press). “But we have changed our emphasis. We had always wanted to add a BankLine and SportsLine and StockLine to the original GameLine, but there was always the question of whether the adults in the family would want to access that kind of information from their kids’ games system.” Out of that concern, which was still very valid, Control Video planned to develop a Master Module for home computers.

But doing so was going to take time which they might not have. After a dismal Christmas, they had racked up $10 million in debt to go along with the $12 million in venture capital they had burned through. It was a glum group of investors who assembled one gray January morning to go over the state of the company. “Goddamn,” said Kimsey after an accountant had run through the painful litany, “we could have sold more of these things selling them off the back of a pickup truck on U.S. 1!” Another person in the room noted that “you’d have thought kids would have shoplifted more than that.” Kimsey sensed that the investors were looking more and more to him alone, swashbuckling war hero that he was, to rescue them from this mess of their own creation. Well, then, he’d do what he could.

In May of 1984, Control Video suddenly recalled all of the Master Modules that were still on store shelves. Far from an ending, everyone hoped this event would mark a new beginning. Von Meister’s silvery tongue had seemingly come through for them, winning them a tentative deal with Bell South, a regional telephone service. The plan was now to reboot and re-brand GameLine, which would henceforward be known as InterLink. They would rent the Master Module for the Atari VCS for $10 per month instead of selling it. More importantly, a new $5 million investment from Bell South would let them start in earnest on a Master Module for home computers.

Like GameLine before it, the InterLink service would only be accessible via Control Video’s own add-on hardware. The first focus would still be games, only now they would be games for the home computers that were in the eyes of the pundits and much of the public the natural, more long-lived successors to the console fad. Von Meister called Interlink “MTV for software”: just as music fans used the music-video channel to decide which albums to buy, InterLink would let computer owners try software before they bought it. (A less strained analogy might have been made with good old radio, but von Meister apparently wanted to show he was down with the latest pop-culture trends.) The service would be tested out initially in Atlanta, Houston, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. “We’re expecting the tests will prove that there’s a broad market for this kind of service,” said von Meister. If that was indeed the case, InterLink would hopefully go nationwide in early 1985. The participation of Bell South, noted Michael Schrage dryly in the Washington Post, “gave the troubled venture some badly needed legitimacy.”

As late as September of 1984, InterLink was still ostensibly on track, although the plan to make new Master Modules for all of the various models of popular home computers had been reluctantly abandoned as impractical; the service would now function using any standard modem. On October 3, Control Video claimed that the first trials would start by the end of the month.

Alas, the trials would never actually begin. At the behest of influential newspaper moguls like Katherine Graham of the Washington Post, who were nervous about the burgeoning era of online information exchange, Congress had recently enacted a law which made it illegal for telephone companies like Bell South to become “information providers,” as opposed to mere conduits for information. Someone — quite possibly a potential competitor like CompuServe or The Source — alerted the Federal Communications Commission to the plans for InterLink, and the FCC secured a court ruling that it should not be allowed to go forward. Six years before, the same entity had foiled a von Meister scheme to use the FM radio band to transmit private data. Now, the government bureaucrats had done it to him again.

Control Video was left high and dry, with no product, no viable plans for a product, no partners, and virtually no money. They did, however, have millions in debt and tens of thousands of useless Atari VCS Master Modules. They thought about selling the latter for salvage to raise some cash, but learned that delivering them to the recycling center would cost more than they’d get paid. So, Control Video chucked the Master Modules in dumpsters to be hauled away with the trash. Any reasonable person who had witnessed that scene play out, pregnant with symbolism as it was, would have shut out the lights and called it a day. Indeed, Bill von Meister, who had already spent more time with Control Video than with most of his startups, was now muttering about doing just that.

His colleagues, though, weren’t all in agreement. Jim Kimsey was a reasonable man in most respects, but he was also an inordinately stubborn one, determined not to allow a bankruptcy to stain his reputation. And young Steve Case, frantic not to be banished back to the life of a Wichita pizza taster, was equally determined to carry on with what could be his only shot at the big time. Bad as things were at Control Video, he personally was already moving up, to heights he could never have dreamed of reaching before middle age at Pizza Hut. While neither von Meister nor Kimsey necessarily saw him as an absolutely vital cog in their machine, he retained the advantage of being cheap. As Kimsey let go of the more expensive people above him, he rose through the ranks, finally winding up as head of marketing by the simple virtue of being the only marketer left standing.

With von Meister already half checked-out mentally and most of the rest of the staff gone, Kimsey the tough old soldier and Case the preppy young yuppie began to form an unlikely bond. Their relationship was a source of constant wonder to their colleagues; it was hard to imagine two men more different in terms of background, personality, or working style. Case, who was a bit of a prude at heart, would cringe and visibly blush when Kimsey would roar into the office on a Monday morning with his war stories from the singles bars; Kimsey took to calling that reaction Case’s “Elmer Fudd” look, and took great pleasure in trying to provoke it. But underneath, despite or perhaps because of all the ribbing, a real affection was evolving. “We found ourselves sort of in a foxhole because we both had aligned ourselves more closely with this company that was kind of going nowhere fast,” Case remembers. They found that they completed one another, and Case’s role at Control Video began to extend well beyond that of a typical marketing manager. Detail-oriented to the core, he put in long hours crunching the numbers and writing the reports that are essential to a smoothly functioning business, while Kimsey, who preferred not to bother with details if he could avoid it, went white-water rafting down the Colorado River or took a bicycle tour through the south of France. “He lived, ate, and breathed this shit,” an admiring Kimsey later remembered of his younger charge. The gregarious former soldier, meanwhile, taught Case, this young man who had always seemed so profoundly uncomfortable in his own skin, a bit about how to handle the back-slapping, social side of business, where the really important relationships are forged on golf courses and in bars as often as they are in executive boardrooms.

As Kimsey and Case developed their partnership, von Meister was increasingly left out in the cold. His final separation from this, his latest visionary but poorly executed venture, came in the first days of 1985. A group of the company’s many creditors was scheduled to come in that day to listen to Kimsey’s pleadings for patience. Given the nature of the visitors, it was essential that the few people still working for Control Video all convey the appropriate sense of austerity. (Not that they would need a lot of help with that: Kimsey had long since sold off all of the office cubicles for cash, cobbling together new dividers out of masking tape and old cardboard boxes.) But then von Meister unexpectedly chose that day to visit the office, roaring up in the shiny new BMW 735i he had just leased.

“How do you like my new car?” he asked as Kimsey and Case looked on aghast.

“We have a creditors meeting!” said Kimsey. “Are you crazy bringing that car? See that tree? They’ll hang you from it!”

“What are you getting all upset about?” asked a wounded von Meister. “Don’t these people understand I have a personal life?”

Kimsey told von Meister in no uncertain terms to get in his new car and go home. This incident signaled the end of von Meister’s association with what would become one of the greatest success stories of its era in American business. Unusually, he walked away from Control Video quietly, without any of the conflict and legal drama that usually marked his exits. Perhaps it had something to do with Jim Kimsey, with whom he had formed a real friendship despite the tensions that inevitably accompanied their assigned roles of dreamer and responsible adult. Even at the end, when he had become an active liability, Kimsey found it impossible to hate von Meister. “He was like a puppy you like a lot but you have to house-train,” he later remembered.

Indeed, underneath all of von Meister’s bravado and guile there always lurked a paradoxical innocence that made it difficult for many who had good reason to hate him to actually manage to do so. At some level, he had remained a child, always chasing after his latest shiny vision. One venture capitalist whom von Meister cost a bundle over the years described him as “like that cartoon character in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. He wasn’t bad; he was just drawn that way.” That so many of his crazy schemes were in fact so visionary makes him one of the great hidden figures behind online life as we know it today. Others may have created the practical technology that allowed the Internet and the World Wide Web to arise and thrive, but Bill von Meister was second to none when it came to the vision thing: online communities, online news, online shopping, digital music delivery, digital software delivery, information as a service… you name it, von Meister was there ahead of almost everyone else. If the execution was usually weak, the core ideas were often prescient, their only drawback being that they were so often a bit too far ahead of their time.

Von Meister died in 1995 at age 53, leaving behind millions in personal debt. The official cause of death was melanoma, but his friends sensed that his body had simply had enough after a life spent burning the candle at both ends, driving race cars or racing yachts when he wasn’t founding companies, drinking and smoking and eating too much, over-indulging in everything in a seeming attempt to swallow whole everything life had to offer. He remained full of ideas until the last. His sister reported at the funeral that he had spent his final days kibitzing over the technological state of the hospital he was in: “When I get out of here alive, if I’m alive, I’m going to show how this hospital can do things better.”

His death was little remarked in the press, meriting no more than the briefest of obituaries in a handful of newspapers close to the Washington Beltway where he had spent the bulk of his career. The corporate star power at his funeral, however, belied his obscure status. Among the cast of former friends and colleagues were Steve Case and Jim Kimsey, now the darlings of Wall Street, who still stood at the helm of what Control Video had become: America Online, the business story of the year if not the decade, and a company which still bore the stamp of many of von Meister’s key insights. A very gracious Case stepped up to deliver a eulogy, saying that “without Bill von Meister there would have been no America Online.” Incredibly, even some of von Meister’s own children had no idea what Case was referring to. “He left behind a series of miserable SOBs who benefited from his ideas,” said another old colleague, rather less graciously. “And yet he was always looking forward to tomorrow’s sunshine in the middle of a monsoon.” But it was yet another who offered perhaps the most cogent eulogy: “He was the most human of human beings I ever knew, and his faults were never disguised.”

(Sources: the books On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and its Founders by Michael A. Banks, Stealing Time: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Collapse of AOL Time Warner by Alec Klein, Fools Rush In: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Unmaking of AOL Time Warner by Nina Munk, and There Must be a Pony in Here Somewhere: The AOL Time Warner Debacle by Kara Swisher; InfoWorld of May 30 1983, July 4 1983, October 31 1983, January 9 1984, April 2 1984, and May 21 1984; Antic of July 1983; Washington Post of November 1 1983 and October 3 1984; the episode of the Computer Chronicles television series entitled “Online Databases, Part 1”; the blog post “The Story of a Pathological Entrepreneur” by John M. Willis.)