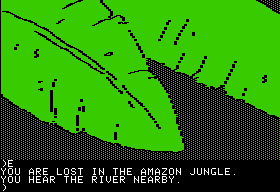

I thought we’d look at Amazon a little differently from the other Telarium games because it is, even more so than the others, very much a visual as well as textual experience. I therefore thought I could best convey the experience of playing it with lots and lots of pictures. It also marks one of the last of the classic Apple II “hi-res adventures,” which whatever their other failings had a unique aesthetic of their own. With the Commodore 64 so eclipsing other gaming platforms by 1984 — remember, Amazon with its long gestation period is in a sense much older than its eventual publication date of late that year — we won’t be seeing a whole lot more of this look. So, let this be our goodbye to one era even as it also represents a prime example of the newer, more sophisticated era of bookware. And anyway things have been kind of dry around here visually for a while now. This blog could use some pictures!

Uniquely for the Telarium line, Amazon lets you choose one of three difficulty levels. I’m playing on the highest difficulty of “Expedition Leader” here, which gives the most to see but is also pretty brutal; death lurks literally everywhere, and comes often (usually?) with no warning whatsoever.

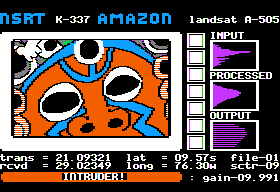

Shay Addams referred to Amazon as an “interactive movie” in his Questbusters review, one of the earlier applications of that term to a computer game. And indeed, the opening sequence is very cinematic, and suitably dramatic. After tuning a receiver to catch the satellite transmission, we watch as the camera pans around the smoking, demolished remnants of the previous Amazon expedition’s campground. It ends with a shot of a member of the cannibal tribe that replaces the killer gorillas of the novel as the architects of all this destruction.

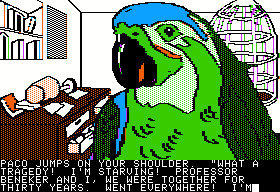

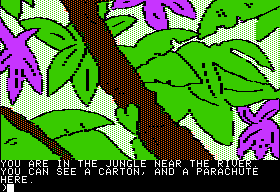

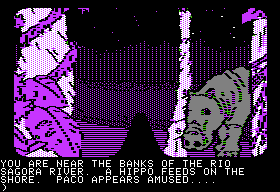

Replacing Amy the signing gorilla is Paco the talking parrot, shown here in this lovely illustration by David Durand. I find him kind of hilarious, but I’m not entirely sure if he was written that way intentionally or not; Crichton, whatever his other strengths, isn’t normally what you’d call a funny writer. Paco at first appears to be a classic adventure-game sidekick/hint system, giving advice constantly throughout the game. In a departure from the norm, however, his advice is, at least on Expedition Leader level, disastrously misguided at least 50% of the time, getting you killed or stranded in all sorts of creative ways. Crichton often stated that he wanted to make a more believable, realistic adventure game. In that spirit, I suppose taking everything said by a talking parrot as gospel might not get you very far in the real world. But then if we’re debating realism we have to also recognize that Paco is basically a cartoon character, even more so than Amy the ridiculously intelligent, loyal, and empathetic gorilla of the novel. Foghorn Leghorn’s got nothing on this guy.

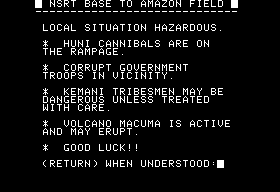

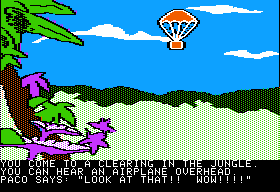

Like in the book, we can use our field computer to link up with NSRT headquarters for regular updates. The above shows the situation just after we’ve parachuted with Paco into the Amazon rain forest. Looks like other than the cannibals and the rampaging government troops and that volcano that’s about to erupt there’s nothing to worry about.

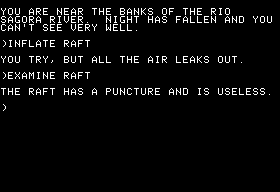

Have I mentioned that it’s easy to die at Expedition Leader level? One wrong move leads to one of a rogue’s gallery of gleefully described death scenes to rival one of the Phoenix games.

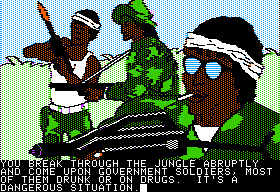

Crichton’s opinion of Peru’s military seems to be no higher than was his opinion of Zaire’s in the novel.

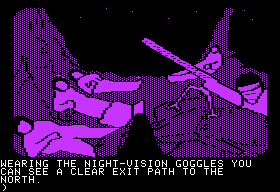

In another strikingly cinematic scene, we use our handy night-vision goggles and an assist from Paco to sneak away from the troops who captured us.

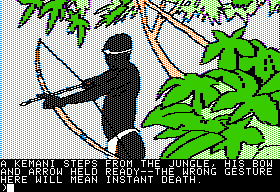

With the “corrupt government troops” behind us, we now get to deal with the Kemani tribesman. Luckily, they like cigarettes and we happen to have a pack.

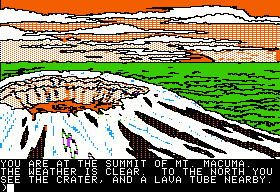

We climb the volcanic Mount Macuma, which separates us from our objective and will soon give us problems in another way.

NSRT airlifts some desperately needed supplies to us. (Why do I want to hear Paco saying “De plane! De plane!” when I see this screenshot?)

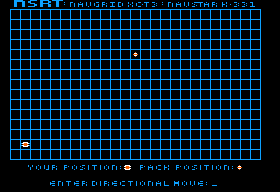

Crichton may have been trying to make a new type of adventure game, but he couldn’t resist including a very old-school maze which we have to navigate to reach the airdropped supplies. This is actually the only part of the game which requires mapping. Normally it’s much more interested in forward plot momentum than the details of geography.

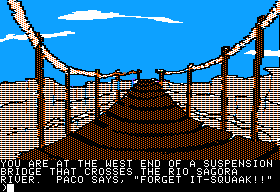

Getting across the river is even more difficult than was getting over the mountain. Once again our night-vision goggles come in handy.

Next morning we find that mischievous monkeys have stolen our supplies. A merry chase follows, implemented as one of Amazon‘s two action games. These were not likely to make arcade owners nervous, but at least they aren’t embarrassingly bad like the action games in Telarium’s other titles. They’re actually kind of engaging in their way; a nice change of pace. Indeed, Amazon‘s way of constantly throwing different stuff at you is one of the most impressive things about it. The screen is constantly changing. “Whatever works for this part of the story” seems to have been Crichton’s philosophy.

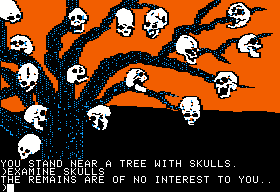

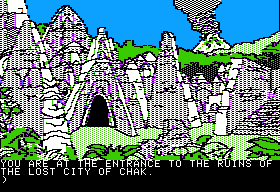

One more obstacle to cross, and we come to the outskirts of the lost city of Chak. It doesn’t exactly look welcoming.

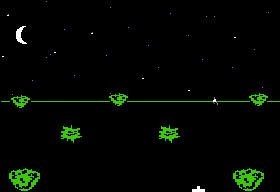

The cannibals attack that night and, in increasing numbers, every night we remain in Chak. The attack is presented as another action game, this time a Space Invaders-like affair which, while not as original or entertaining as the monkey chase, is at least competently executed.

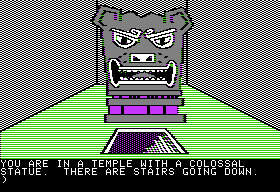

We have about five days in Chak before the volcano erupts. If that sounds generous, know that it’s really not; time passes devilishly quickly. Our main objective is to find the secret staircase that will take us to the endgame.

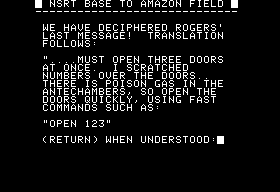

The endgame requires us to open a series of doors in the correct order using clues found onscreen — one of the few classically adventure-gamey puzzles you’ll find in Amazon. The correct sequence for the above, for example, is 1-3-2. I assume this is because there are 9 marks on the first door, 13 on the second, and 11 on the third. At any rate my first instinct was to arrange them in numerical sequence, and it worked.

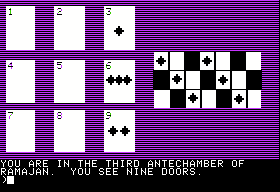

The final sequence is, to say the least, a bit more tricky. Now we have nine doors to contend with. This puzzle, which appears only at Expedition Leader level, stumped me entirely and forced me to a walkthrough. If you can solve it, or even just give the methodology for solving it given the correct answer, I’d love to hear about it. To see the answer, highlight the empty space that follows: 3-4-8-1-5-9-2-6-7.

Get past the last of the doors and we come to enough emeralds to warm any greedy adventurer’s heart. And after that, to quote Neal Stephenson, “It’s just a chase scene,” as we rush to get away from the erupting volcano.

Crichton wouldn’t return to computer games until some fifteen years after Amazon. It’s not hard to understand why. Even if Amazon sold 100,000 copies, his earnings from it would have been a drop in the bucket compared to what he earned from his books and movie licenses. Yet Amazon is good enough that it makes me wish he had done more work in interactive mediums.

Which is not to say that it doesn’t have its problems. The parser is no better than you might expect from such a one-off effort; on at least one or two occasions I knew exactly what to do but had to turn to the walkthrough to figure out how to say it to the game. And the story logic often has little to do with real-world logic. If you don’t do everything just right in the opening stages of the game, for instance, your flight to Peru will get hijacked and you’ll end up dead after the game toys with you a bit — this despite there being no logical reason why your previous failings should have led to your flight getting hijacked.

Still, Amazon is a unique experience, as I hope the pictures above convey. Especially if played on one of the less masochistic levels, it’s a fast-moving rush of a game that’s constantly throwing something new and interesting at you. And it really is relentlessly cinematic, replete with stylish little touches. Even when it’s working with just text, words often stutter onto the screen in clumps to mimic conversation, or are pecked out character by character when they’re coming through your satellite computer hookup. There’s a sense that things could go in any direction, that anything could be asked of you next, rules of computer-game genres be damned. If that sounds appealing, by all means download it, fire up your Apple II emulator, and give it a go.