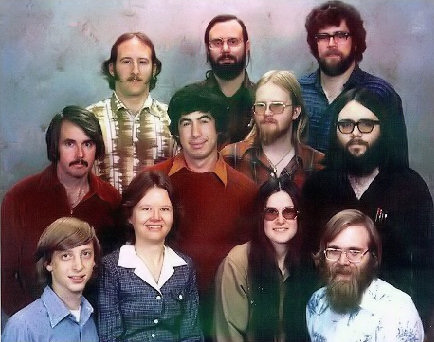

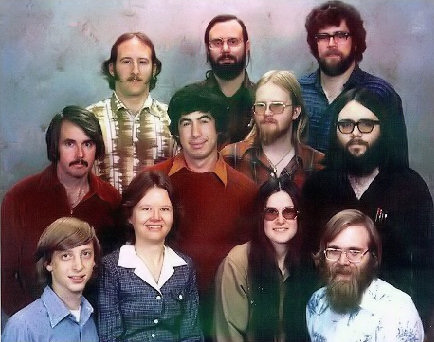

There’s a good chance that you’ve received a forwarded email at least once or twice during the past ten years or so with the photograph above and a snarky caption such as, “Would you have invested?” The picture shows eleven of the thirteen Microsoft employees as of December 7, 1978, just before the company decamped from its first home in Albuquerque, New Mexico (initially chosen because it was the home of Microsoft’s first customer, the now increasingly irrelevant MITS) for the big time in Seattle. The twelve-year-old at the bottom left is of course Bill Gates himself… and, believe it or not, he’s actually already 23 there.

Ah, what can I say about Bill? I suppose you don’t become a multi-billionaire without leaving some bruised egos in your wake, but old Bill has always had a special knack for pissing people off and generally coming off like the computer industry’s own version of Darth Vader. In the abstract, I’m not sure that he was really so much more evil than most of his peers. Even by the time this photo was taken, the digital utopianism of the People’s Computer Company and Creative Computing was beginning to take a beating from a whole lot of would-be titans of industry looking to get a piece of the new microcomputer action — people like Commodore head Jack Tramiel, who announced that “business is war” and then wondered why all of his business partners and employees were so surprised when he lied to them and betrayed them; or like Steve Jobs, who even before co-founding Apple swindled his best friend out of a $5000 bonus he had earned doing his job for him, disingenuously prattling on about hippie togetherness and Eastern philosophy all the while. Perhaps the closest to moral in this lot was the management of Tandy, who were so unimaginative and so out of touch with their competitors that they couldn’t really be bothered to actively try to wrong them.

The big difference with Gates was that he was so damned good at being evil. While everyone else wound up to one degree or another hoisted from their own petards for their misdeeds, Gates just prospered. He wasn’t so much immoral as amoral. Unlike Tramiel, who seemed to positively revel in his evil, or Jobs, who desperately wanted to be seen as the good guy whatever dirty tricks he was pulling behind the scenes, Gates seemed utterly indifferent to his image and utterly disinterested in the niceties of right and wrong. On a personal level, he seems to have inspired something between ambivalence and out-and-out dislike in everyone who wasn’t directly depending on him for their salary (or, perhaps, the latter group just couldn’t speak up about it). It wasn’t just that his personal hygiene left as much to be desired as his interpersonal skills. Nor was it just that he displayed all the arrogance of both a brilliant programmer and the Harvard scion of a prosperous family; that was to be expected, considering that he was both of these things. No, it was the sheer magnitude of Gates’s need to win and to dominate those around him that made him downright disturbing to be around for so many people. If Gates couldn’t win at something fairly, one never doubted that he would cheat. Hell, if he could win at something fairly but it was just easier to cheat, he’d probably choose the latter course there as well. But, here’s the thing: Gates always cheated smart. If ethics didn’t mean much to him, he was very aware of legalities, and always careful to make sure that even at his shadiest he stayed on the right side of that line. (Of course, he became increasingly less good at that in the 1990s, but that’s a story for another time…) Remember the blinkered MIT nerds that Joseph Weizenbaum railed against in Computers and Human Reason? Well, the young Gates fit that stereotype perfectly, with an added heaping measure of cold-blooded ruthlessness. His wasn’t a personality likely to win a lot of friends. As an investment opportunity, however…

The story of Microsoft Adventure provides a good early illustration of both the very real technical and marketing acumen of Gates’s company and its genius for ignoring ethical considerations while still staying on the right side of the law. It provides an early example of what was already becoming the company’s modus operandi, one guaranteed to piss off idealistic hackers as much as it would delight its financial backers. And, not incidentally, it also represents a very important moment in the continuing evolution of adventure games.

In 1979, fully two years before Gates’s genius stroke in partnering with IBM on the original IBM PC, Microsoft was already a very big fish in the still relatively small pond that was the microcomputer industry of the era, having built a strong business upon the solid foundation of that initial Altair BASIC. In fact, Microsoft was simply the company to go to for a microcomputer BASIC implementation; it provided not only the TRS-80 Level 2 BASIC, but also the BASICs in the Commodore PET and the just-released Apple II Plus. It had also already expanded into other high-level programming languages, producing the first implementations of FORTRAN and COBOL to appear on microcomputers. Microsoft Adventure was part of a new initiative for 1979, the Microsoft Consumer Products Division, which aimed to market games and less esoteric applications to everyday consumers. The division as a whole was arguably somewhat ahead of its time, and would not be a rousing success in the long term. (Microsoft gave up on it within a few years to focus almost exclusively on technical and business products, and, the long-lived oddity Flight Simulator aside, would not begin marketing games and applications directly to home users once again until the 1990s.) For now, though, Consumer Products was big at Microsoft. With adventure games becoming so big on the TRS-80, when an employee named Gordon Letwin said he could port the original Crowther and Woods Adventure, something of a semi-legendary holy grail to microcomputer adventurers, onto the little machine, the go-ahead wasn’t long in coming.

Gordon Letwin is the bearded, black-haired fellow at the far right of the second row in the picture above. Born in 1952 and thus three years older than Bill Gates himself, his character and background is not too far removed from that of other hackers we’ve already met on this blog. A withdrawn, almost disturbingly nonverbal personality, Letwin read non-fiction books by the dozen throughout his childhood and teen years. Upon entering Purdue University as a physics major (the same major Will Crowther had chosen a decade earlier), Letwin found his real calling in the university’s computer center. After university, he got a job with Heath Company, who were well known among electronics hobbyists of the time for their “Heathkits,” do-it-yourself kits that let hobbyists build test equipment, amplifiers, radios, even televisions. In 1977 the line was expanded to include a computer, the H8, for which Letwin designed a simple operating system called H-DOS. He also designed a BASIC of his own, but a young and aggressive Gates, much to Letwin’s chagrin, dropped in on Heath while making the rounds of microcomputer manufacturers to try to convince them to buy Microsoft’s version. Letwin did something interesting, something that few others would ever do: he stood up to Gates. In Gates’s own words:

“There are different ways to do this stuff. His had some advantages which he was pointing out to me. We ended up in this argument between two technical guys. There were about 15 people in the room and no one else could follow along. We’re talking all in terms of data structure, single representations, double scan, stuff like that… Like if you typed a bad line, his would immediately check the syntax, and mine wouldn’t. Which is one of the negative points of our design. Anyway, he was being very sarcastic about that, telling me how dumb that was.”

Deciding perhaps that the adage that no one ever got fired for buying Microsoft was true even in 1977, Heath’s management elected to replace Letwin’s in-house design with Microsoft’s BASIC. This left them with one very angry Letwin. Gates, who whatever his other failings knew talent when he saw it, poached him for Microsoft about nine months later, not too terribly long before the above photograph was taken.

Although Letwin and his wife lived very modestly even years after Microsoft had made them wealthy, he more so than most hackers always knew the value of a buck, and always wanted to get what was coming to him. A 1988 Seattle Times profile alleges that he was a major impetus behind the decision of Gates and Paul Allen to transform Microsoft from a partnership to a corporation in 1981, and to grant him and other early employees like him the shares that would make them very rich indeed by the end of the decade. I mention this here because it may explain something odd about Microsoft Adventure: it was published by Microsoft, but allegedly developed by an entity called Softwin Associates, a company that apparently consisted of only Letwin himself. It seems that Letwin developed Adventure as something of a moonlighting project, then licensed it back to his employer. Why do it that way? Well, doing so gave Letwin the ability to collect royalties on sales as an outside contractor, above and beyond his regular employee salary. That the very finances-focused Gates let him get away with such a scheme probably says a lot about his perceived value to the company.

As Microsoft claimed in the instruction manual, “With Microsoft Adventure, you have the complete version of the original Adventure. Nothing has been left out of the original DEC version.” That stands as quite a neat trick; remember that Scott Adams, himself an experienced programmer, had not even tried to do a direct port but had instead developed Adventureland as its own, much smaller game. How did Letwin manage it?

He first of all took advantage of Radio Shack’s expansion interface, which allowed the user both to expand memory beyond 16 K and to replace cassette-based storage with floppy disks. This was a bold choice in its way, dramatically limiting the potential buyers of Adventure; in its September, 1979, issue, SoftSide reported that “only a few” of its readers had yet bought Radio Shack’s $500 disk drive. Yet Adventure would have been impossible without it.

The benefits of expanded memory were obvious in allowing longer and more complex programs, but those of the floppy disk were both obvious and more subtle. On the obvious level, the floppy was superior to the cassette in every way, allowing users to store much more data on a single piece of media and to save and retrieve it many times faster and with many times the reliability. But another attribute of the floppy would be key to the implementation of major games like Adventure given the still tiny amount of memory 32 K actually is. Unlike the cassette, the floppy was a random-access storage device, meaning the TRS-80 could be programmed to load into memory chunks of data from all over the disk as a program ran. By comparison, reading from the cassette required that the user manually position the tape in the correct position using the player’s counter, then press play… and then, of course, wait, for up to 20 minutes just to load one of Scott Adams’s simple adventures. With a disk drive, then, Letwin could leave all of that text that was stored in an external file even in Crowther and Woods’s original on the disk, loading in only the bit and pieces that he needed as they were needed. He needed only pack the core code of the game itself into his 32 K — not that that was a trivial task in itself, requiring as it did that Letwin port the original FORTRAN code into Z80 assembly language while optimizing everywhere for speed and size. Letwin’s pioneering use of the disk drive as a sort of auxilliary memory would soon enough be everywhere, refined to something of an art by companies like Infocom. Countless classic games would have been simply impossible without it.

The arrival of disk drives also brought with them another, less welcome innovation: copy protection. Every computer has a standard format in which it arranges data on its disks. To simplify rather extremely, locations on the disk are broken down into track and sector numbers, with a master directory stored in some standard location that records all of the files stored on the disk and their location by track and sector; this allows the computer to locate and retrieve files as they are requested. Most early disk copying programs assumed that the disk being copied would be laid out in this standard format, and would simply attempt to copy each file they found in the master directory over to the new disk one by one. It was, however, relatively easy for a program like Adventure to replace the standard disk format with one of its own devising — one that it knew how to read, but which would completely flummox another program expecting a standard format. By later standards, Adventure‘s copy protection was relatively simple, just rearranging the numbering scheme used to identify the different sectors on the disk. It was also relatively kind in allowing at least those with two disk drives to make a single backup copy by entering a special command within the program itself. Later protection schemes would get much more sophisticated, and much less kind.

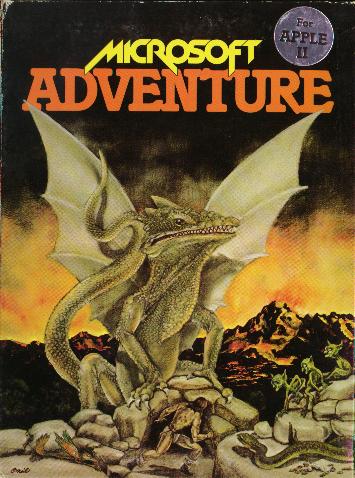

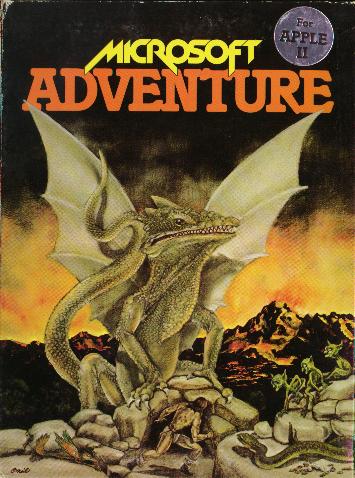

Microsoft Adventure also points toward the future in its packaging. It shipped in a real box with real, professionally produced artwork and a multi-page, glossy manual written by Dottie Hall. Contrast this with the packaging of the early Scott Adams games, constructed from a plastic sandwich bag, a business card, and a baby formula liner. In 1979, Microsoft was one of the few software companies with the resources to give its products a professional presentation. As the games industry grew more professional and profitable, however, packaging would become a huge part of the whole experience of adventuring, reaching glorious (some might say absurd) heights of lurid artwork, lengthy manuals, included novellas or even novels, elaborate maps (sometimes from cloth or parchment), and evocative physical props (“feelies”).

Microsoft Adventure also started another, related trend that became almost as prevalent: its artwork has almost nothing to do with the actual game it represents.

I certainly never imagined the jokey response to “KILL DRAGON” (“CONGRATULATIONS! YOU HAVE JUST VANQUISHED A DRAGON WITH YOUR BARE HANDS!”) playing out quite like that. Although, I guess with sufficient imagination…

Having dwelt on the original DEC versions at length, there’s not really that much to say about the actual playing experience of the version of Adventure that Letwin developed. It is exactly what Microsoft claimed it to be, a slavishly faithful port of the original, minus only such PDP-centric niceties as “cave hours.” I suspect that most of the in-game text is literally the same as that on the PDP original, being the original’s external data file simply copied over to a TRS-80 floppy. Interestingly, Letwin does make an effort to ease some of the original’s more nonsensical puzzles. In the original, for instance, one could earn the “last lousy point” only by dropping the Spelunker Today magazine at Witt’s End, a completely unmotivated action; in Letwin’s version, reading the magazine yields the vital clue that “ITS ADDRESSED TO WITTS END!” Even better, the richly described but previously useless “Breath-Taking View” now has a purpose of sorts, for Letwin adds a single line that helps out with another notorious puzzle: “WORDS OF FIRE, APPARENTLY HANGING IN AIR, SAY ‘PLOVER.'” What a guy!

Nudges like that aside, Letwin makes just one addition, the “Software Den.”

YOU ARE IN A STRANGE ROOM WHOSE ENTRANCE WAS HIDDEN BEHIND THE CURTAINS. THE FLOOR IS CARPETED, THE WALLS ARE RUBBER, THE ROOM IS STREWN WITH PAPERS, LISTINGS, BOOKS, AND HALF-EMPTY DR. PEPPER BOTTLES. THE DOOR IN THE SOUTH WALL IS ALMOST COVERED BY A LARGE COLOUR POSTER OF A NUDE CRAY-1 SUPERCOMPUTER.

A SIGN ON THE WALL SAYS, “SOFTWARE DEN.”

THE SOFTWARE WIZARD IS NOWHERE TO BE SEEN.

THERE ARE MANY COMPUTERS HERE, MICROS, MINIS, AND MAXIS.

Messing with any of the computers results in:

AS YOU REACH FOR THE ELECTRONIC GOODIES, AN ENRAGED BEARDED PROGRAMMER JUMPS OUT OF CONCEALMENT. “AHA!” HE CROWS, “I’VE FOUND THE SOB (THAT’S ‘SUBTRACT-ONE-AND-BRANCH’) THAT’S BEEN STEALING MY EQUIPMENT! HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN THAT MY WIZARDLY SPELLS HELP KEEP THIS CAVE TOGETHER? FIRST, I’LL REMOVE SOME OF THE TREASURES:

DESTROY (TREASURES);

THEN, I’LL REVOKE SOME MAGIC WORDS:

REVOKE (MAGICWORDS);

FINALLY, I’LL KICK YOU DEEP INTO THE MAZE!”

YOURLOC = DEEP.IN.MAZE;

YOU ARE IN A MAZE OF TWISTING LITTLE PASSAGES, ALL DIFFERENT.

Talk about your delusions of grandeur…

But now we come to the elephant in the room: the question of credit. At no place in the Microsoft Adventure program or its accompanying documentation do the names of Crowther and Woods appear. We are told only that “Adventure was originally written in FORTRAN for the DEC PDP-10 computer,” as if it were the result of a sort of software immaculate conception. Needless to say, Crowther and Woods were never contacted by Microsoft at all, and received no royalties whatsoever for a program that by all indications turned into quite a nice seller for the company; it was later ported to the Apple II, and was one of the programs IBM wanted available at day one for the launch of its new PC in 1981. Because Crowther and Woods, immersed in old-school hacker culture as they were, never even considered trying to assert ownership over their creation, Microsoft violated no laws in doing this. However, the ethics of cloning someone else’s game design and lifting all of their text literally verbatim, and then copy protecting it (the irony!) and selling it… well, I don’t think that calling it “ethically dubious” is going too far out on a limb. In his famous “Open Letter to Hobbyists” of 1976, Gates asserted the moral right of the creators of software to have control over their creations. How to reconcile that stance with Microsoft Adventure? Incidents of commercial co-option of free software like this one are what eventually led to the creation of licenses like the GPL, designed to make sure that free software stays free. If you’ve ever wondered why so many in the open-source communities are so obsessed with the vagaries of licenses, maybe stories like this one will give an idea.

Be that as it may, Gates now seems as dedicated to doing good in the world and giving away his money as he once was to crushing his business competition and amassing it, to which I give a big hooray. I’d say that saving a single child makes up for the dubious aspects of Microsoft Adventure many times over. Gordon Letwin, meanwhile, also stayed with Microsoft for many years, going on to head the ill-fated OS/2 project before retiring on all that stock in 1993. He now also devotes himself to charity, specifically to environmental causes. A second hooray there.

Ironically, Microsoft Adventure is such a perfect clone of the original that it is now the ideal choice of anyone who wants to experience said original in as authentic a form as possible without building a whole virtual PDP-10 of their own. I’ve made a TRS-80 disk image of it available here, which will stay up as long as Microsoft’s lawyers don’t come after me for pirating their stolen 32-year old software and talking bad about their “non-executive chairman,” but for an easier time of things you might want to hunt down the IBM PC version on an abandonware site. If you do go with the TRS-80, you’ll have to play it using the SDLTRS emulator rather than the MESS version, as, due to the on-disk copy protection mentioned earlier, the disk image has to be stored in the “DMK” format — a format that MESS unfortunately cannot read. Really sorry about that!

I’ll be looking at text adventures in 1980 — a very exciting year — soon. But next I want to make a little detour into some theory and then into another genre of story-oriented game.