On a beautiful May day in 1987, Epyx held a party behind their offices to celebrate the completion of California Games, the fifth and latest in their hugely popular Games line of sports titles. To whatever extent their skills allowed, employees and their families tried to imitate the athletes portrayed in the new game, riding skateboards, throwing Frisbees, or kicking around a Hacky Sack. Meanwhile a professional BMX freestyler and a professional skateboarder did tricks to show them how it was really done. The partiers dressed in the most outrageous beachwear they could muster — typically for this hyper-competitive company, their outfits were judged for prizes — while the sound of the Beach Boys and the smell of grilling hamburgers and hotdogs filled the air. Folks from the other offices around Epyx’s came out to look on a little wistfully, doubtless wishing their company was as fun as this one. A good time was had by all, a memory made of one of those special golden days which come along from time to time to be carried along with us for the rest of our lives.

Although no one realized it at the time, that day marked the high-water point of Epyx. By 1990, their story would for all practical purposes be over, the company having gone from a leading light of its industry to a bankrupt shell at the speed of business.

In the spring of 1987, Epyx was the American games industry’s great survivor, the oldest company still standing this side of Atari and the one which had gone through the most changes over its long — by the standards of a very young industry, that is — lifespan. Epyx had been founded by John Connelly and Jon Freeman, a couple of tabletop role-players and wargaming grognards interested in computerizing their hobbies, way back in 1978 under the considerably less exciting name of Automated Simulations. They hit paydirt the following year with Temple of Apshai, the most popular CRPG of the genre’s primordial period. Automated Simulations did well for a while on the back of that game and a bevy of spinoffs and sequels created using the same engine, but after the arrival of the more advanced Wizardry and Ultima their cruder games found it difficult to compete. In 1983, a major management shakeup came to the moribund company at the behest of a consortium of investors, who put in charge the hard-driving Michael Katz, a veteran of the cutthroat business of toys. Katz acquired a company called Starpath, populated by young and highly skilled assembly-language programmers, to complete the transformation of the stodgy Automated Simulations into the commercially aggressive Epyx. In 1984, with the release of the huge hits Summer Games and Impossible Mission, the company’s new identity as purveyors of slick action-based entertainments for the Commodore 64, the most popular gaming platform of the time, was cemented. One Gilbert Freeman (no relation to Jon Freeman) replaced Katz as Epyx’s president and CEO shortly thereafter, but the successful template his predecessor had established remained unchanged right through 1987.

By 1987, however, Freeman was beginning to view his company’s future with some trepidation despite the commercial success they were still enjoying. The new California Games, destined for yet more commercial success though it was, was ironically emblematic of the long-term problems with Epyx’s current business model. California Games pushed the five-year-old Commodore 64’s audiovisual hardware farther than had any previous Epyx game — which is to say, given Epyx’s reputation as the absolute masters of Commodore 64 graphics and sound, farther than virtually any other game ever released for the platform, period. This was of course wonderful in terms of this particular game’s commercial prospects, but it carried with it the implicit question of what Epyx could do next, for even their most technically creative programmers were increasingly of the opinion that they were reaching an end point where they had used every possible trick and simply couldn’t find any new ways to dazzle. For a company so dependent on audiovisual dazzle as Epyx, this was a potentially deadly endgame.

Very much in tandem with the question of how much longer it would be possible to continue pushing the audiovisual envelope on the Commodore 64 ran concerns about the longevity of the platform in general. Jack Tramiel’s little computer for the masses had sold more and longer than anyone could ever have predicted, but the ride couldn’t go on forever. While Epyx released their games for other platforms as well, they remained as closely identified with the Commodore 64 as, say, Cinemaware was with the Commodore Amiga, with the 64 accounting for well over half of their sales most quarters. When that market finally took the dive many had been predicting for it for years now, where would that leave Epyx?

It was for these big-picture reasons that Freeman brought a man with a reputation for big-picture vision onto Epyx’s board in January of 1987. All but unknown though he was to the general public, among those working in the field of home computers Dave Morse had the reputation of a veritable miracle worker. Just a few years before, he had found ways to let the brilliant engineering team at Amiga, Incorporated, create a computer as revolutionary in its way as the Apple Macintosh on a budget that would barely have paid Steve Jobs’s annual salary. And then, in a coup worthy of The Sting, he’d proceeded to fleece Atari of the prize and sail the ship of Amiga into the (comparatively) safe harbor of Commodore Business Machines. If, as Freeman was starting to suspect, it was going to become necessary to completely remake and remodel Epyx for a second time in the near future, Morse ought to be a darn good man to have on his team.

And indeed, Morse didn’t fail to impress at his first Epyx board meetings. In fact, he impressed so much that Freeman soon decided to cede much of his own power to him. He brought Morse on full-time as CEO to help run the company as an equal partner in May of 1987, the very month of the California Games cookout. But California Games on the Commodore 64 was the present, likely all too soon to be the past. For Freeman, Morse represented Epyx’s future.

Morse had a vision for that future that was as audacious as Freeman could possibly have wished. In the months before coming to Epyx, he had been talking a lot with RJ Mical and Dave Needle, two of his star engineers from Amiga, Incorporated, in the fields of software and hardware respectively. Specifically, they’d been discussing the prospects for a handheld videogame console. Handheld videogames of a sort had enjoyed a brief bloom of popularity in the very early 1980s, at the height of the first great videogame boom when anything that beeped or squawked was en vogue with the country’s youth. Those gadgets, however, had been single-purpose devices capable of playing only one game — and, because it was difficult to pack much oomph into such a small form factor, said game usually wasn’t all that compelling anyway. But chip design and fabrication had come a long way in the past five years or so. Mical and Needle believed that the time was ripe for a handheld device that would be a gaming platform in its own right, capable of playing many titles published on cartridges, just like the living-room-based consoles that had boomed and then busted so spectacularly in 1983. For that reason alone, Morse faced an uphill climb with the venture capitalists; this was still the pre-Nintendo era when the conventional wisdom held videogame consoles to be dead. Yet when he joined the Epyx board he found a very sympathetic ear for his scheme in none other than Epyx President Gilbert Freeman.

In fact, Freeman was so excited by the idea that he was willing to bet the company on it; thus Morse’s elevation to CEO. The plan was to continue to sell traditional computer games while Mical and Needle, both of whom Morse hired immediately after his own appointment, got down to the business of making what everybody hoped would be their second revolutionary machine of the decade. It would all happen in secret, while Morse dropped only the vaguest public hints that “it is important to be able to think in new directions.” This was by any measure a very new direction for Epyx. Unlike most game publishers, they weren’t totally inexperienced making hardware: a line of high-end joysticks, advertised as the perfect complement to their games, had done well for them. Still, it was a long way from making joysticks to making an entirely new game console in such a radically new form factor. They would have to lean very heavily on Morse’s two star engineers, who couldn’t help but notice a certain ironic convergence about their latest situation: Amiga, Incorporated, had also sold joysticks among other gaming peripherals in an effort to fund the development of the Amiga computer.

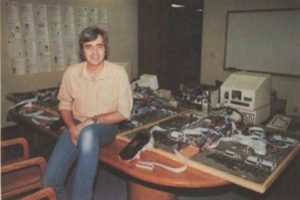

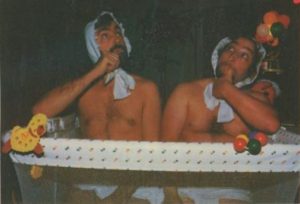

RJ Mical and Dave Needle in a very… disturbing picture. Really, perhaps it’s best if we don’t know any more about what’s going on here.

RJ Mical and Dave Needle were a pair of willfully eccentric peas in a pod; one journalist called them the Laurel and Hardy of Silicon Valley. While they had worked together at Amiga for quite some time by June of 1984, the two dated the real genesis of their bond to that relatively late date. When Amiga was showing their Lorraine prototype that month at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, they found themselves working together really closely for the first time, doing some jerry-rigging to get everything working for the demonstrations. They discovered that they understood each other in a way that “software guys” and “hardware guys” usually do not. “He was the first software guy I ever met,” remembered Needle in a joint 1989 interview, “who had more than an inkling of the real purpose of my work, which is building hardware platforms that you can launch software from.” “I could never get hardware guys to understand what I was doing,” interrupted Mical at this point in the same interview. “Dave couldn’t get software guys to understand what the guts could handle. We found ourselves a great match.” From that point forward, they were inseparable, as noted for their practical jokes and wacky antics as for their engineering brilliance. It was a true meeting of the minds, the funny bones, and, one might even say, the hearts. As illustrated by the exchange I’ve just quoted, they became the kind of friends who freely complete each other’s thoughts without pissing each other off.

The design they sketched for what they liked to call the “Potato” — for that was envisioned as its rough size and shape — bore much the same philosophical stamp as their work with Amiga. To keep the size and power consumption down, the Potato was to be built around the aged 8-bit 6502, the chip at the heart of the Commodore 64, rather than a newer CPU like the Amiga’s 68000. But, as in the Amiga, the chip at the Potato’s core was surrounded with custom hardware designed to alleviate as much of the processing burden as possible, including a blitter for fast animation and a four-channel sound chip that came complete with digital-to-analog converters for playing back sampled sounds and voices. (In the old Amiga tradition, the two custom chips were given the names “Suzy” and “Mikey.”) The 3.5-inch LCD display, with a palette of 4096 colors (the same as the Amiga) and a resolution of 160 X 102, was the most technologically cutting-edge and thus for many months the most problematic feature of the design; Epyx would wind up buying the technology to make it from the Japanese watchmaker Citizen, who had created it as the basis for a handheld television but had yet to use it in one of their own products. Still, perhaps the Potato’s most innovative and impressive feature of all was the port that let you link it up with your mates’ machines for multiplayer gaming. (Another visionary proposed feature was an accelerometer that would have let you play games by tilting the entire unit rather than manipulating the controls, but it would ultimately prove just too costly to include. Ditto a port to let you connect the Potato to your television.)

While few would question the raw talent of Mical and Needle and the small team they assembled to help them make the Potato, this sort of high-wire engineering is always expensive. Freeman and Morse estimated that they would need about two years and $4 million to bring the Potato from a sketch to a finished product ready to market in consumer-electronics stores. Investing this much in the project, it seemed to Freeman and Morse, should be manageable based on Epyx’s current revenue stream, and should be a very wise investment at that. Licking their chops over the anticipated worldwide mobile-gaming domination to come, they publicly declared that Epyx, whose total sales had amounted to $27 million in 1987, would be a $100 million company by 1990.

At first, everything went according to plan. Upon its release in the early summer of 1987, California Games became the hit everyone had been so confidently anticipating. Indeed, it sold more than 300,000 copies in its first nine months and then just kept on selling, becoming Epyx’s biggest hit ever. But after that nothing else ever went quite right for Epyx’s core business. Few inside or outside of the company could have guessed that California Games, Epyx’s biggest hit, would also mark the end of the company’s golden age.

From the time of their name change and associated remaking up through California Games, Epyx had been almost uniquely in touch with the teenage boys who bought the vast majority of Commodore 64 games. “We don’t simply invent games that we like and hope for the best,” said Morse, parroting Epyx’s official company line shortly after his arrival there. “Instead, we pay attention to current trends that are of interest to teenagers. It’s similar to consumer research carried out by other companies, except we’re aiming for a very specific group.” After California Games, though — in fact, even as Morse was making this statement — Epyx lost the plot of what had made the Games line so successful. Like an aging rock star grown fat and complacent, they decided to join the Establishment.

When they had come up with the idea of making Summer Games to capitalize on the 1984 Summer Olympics, Epyx had been in no position to pay for an official Olympic license, even had Atari not already scooped that up. Instead they winged it, producing what amounted to an Olympics with the serial numbers filed away. Summer Games had all the trappings — opening and closing ceremonies; torches; national anthems; medals of gold, silver, and bronze — alongside the Olympic events themselves. What very few players likely noticed, though, was that it had all these things without ever actually using the word “Olympics” or the famous (and zealously guarded) five-ring Olympic logo.

Far from being a detriment, the lack of an official license had a freeing effect on Epyx. Whilst hewing to the basic templates of the sports in question, they produced more rough-and-ready versions of same — more the way the teenage boys who dominated among their customers would have liked the events to be than the somewhat more staid Olympic realities. Even that original Summer Games, which looked itself a little staid and graphically crude in contrast to what would follow, found room for flashes of wit and whimsy. Players soon learned to delight in an athlete — hopefully not the one they were controlling — landing on her head after a gymnastics vault, or falling backward and cracking up spectacularly instead of clearing the pole vault. Atari, who had the official Olympic license, produced more respectful — read, boring — implementations of the Olympics that didn’t sell particularly well, while Summer Games blew up huge.

Seeing how positively their players responded to this sort of thing, Epyx pushed ever further into the realm of the fanciful in their later Games iterations. World Games and California Games, the fourth and fifth title in the line respectively, abandoned the Olympics conceit entirely in favor of gathering up a bunch of weird and wild sports that the designers just thought would be fun to try on a computer. In a final act of Olympics sacrilege, California Games even dropped the national anthems in favor of having you play for the likes of Ocean Pacific or Kawasaki. As California Games so amply demonstrated, the Games series as a whole had never had as much to do with the Olympics or even sports in general as it did with contemporary teenage culture.

But now Epyx saw another Olympics year fast approaching (during this period, the Winter and Summer Olympics were still held during the same year rather than being staggered two years apart as they are today) and decided to come full circle and then some, to make a pair of Games games shrouded in the legitimacy that the original Summer Games had lacked. Epyx, in other words, would become the 1988 Olympics’s version of Atari. In October of 1987, they signed a final contract of over 40 pages with the United States Olympic Committee (if ever a gold medal were to be awarded in legalese and bureaucratic nitpicking, the Olympic Games themselves would have to be prime contenders). Not only would Epyx have to pay a 10 percent royalty to the Olympic Committee for every copy of The Games: Winter Edition and The Games: Summer Edition that they sold, but the same Committee would have veto rights over every aspect of the finished product. Giving such authority to such a famously non-whimsical body inevitably spelled the death of the series’s heretofore trademark sense of whimsy. While working on the luge event a developer came up with the idea of sending the luger hurling out of the trough and into outer space after a major crash. The old Epyx would have been all over it with gusto. But no, said the stubbornly humorless Committee in their usual literal-minded fashion, lugers don’t ever exit the trough when they crash, they only spill over inside it, and that’s how the computer game has to be as well.

When The Games: Winter Edition appeared right on schedule along with the Winter Olympics themselves in February of 1988, it did very well out of the gate, just like any other Games game. Yet in time the word spread through the adolescent grapevine that this latest Games just wasn’t as much fun as the older ones. In addition to the stifling effect of the Olympic Committee’s bureaucracy, its development had been rushed; because of the need to release the Winter Edition to coincide with the real Winter Olympics, it had had to go from nothing to boxed finished product in just five months. The Summer Edition, which appeared later in the year to coincide with the Summer Olympics, was in some ways a better outing, what with Epyx having had a bit more time to work on it. But something was still missing. California Games, a title Epyx’s core teenage demographic loved for all the reasons they didn’t love the two stodgy new officially licensed Games, easily outsold both of them despite being in its second year on the market. That was, of course, good in its way. But would the same buyers turn out to buy the next big Games title in the wake of the betrayal so many of them had come to see the two most recent efforts to represent? It wasn’t clear that they would.

The disappointing reception of these latest Games, then, was a big cause of concern for Epyx as 1988 wore on. Their other major cause for worry was more generalized, more typical of their industry as a whole. As we’ve seen in an earlier article, 1988 was the year that the Nintendo Entertainment System went from being a gathering storm on the horizon to a full-blown cyclone sweeping across the American gaming landscape. Epyx was hardly alone among publishers in feeling the Nintendo’s effect, but they were all too well positioned to get the absolute worst of it. While they had, generally with mixed results, made occasional forays into other genres, the bulk of their sales since the name change had always come from their action-oriented games for the Commodore 64 — the industry’s low-end platform, one whose demographics skewed even younger than the norm. The sorts of teenage and pre-teen boys who had once played on the Commodore 64 were exactly the ones who now flocked to the Nintendo in droves. The Christmas of 1988 marked the tipping point; it was at this point that the Nintendo essentially destroyed the Commodore 64 as a viable platform. “Games can be done better on the 64 than on a Nintendo,” insisted Morse, but fewer and fewer people were buying his argument. By this point, many American publishers and developers had begun to come to Nintendo, hat in hand, asking for permission to publish on the platform, but this Epyx refused to do, being determined to hold out for their own handheld console.

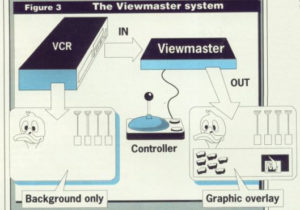

It’s not as if the Commodore 64’s collapse entirely sneaked up on Epyx. As I noted earlier, Gilbert Freeman had been aware it might be in the offing even before he had hired Dave Morse as CEO. Over the course of 1987 and 1988, Epyx had set up a bulwark of sorts on the higher-end platforms with a so-called “Masters Collection” of more high-toned and cerebral titles, similar to the ones that were continuing to sell quite well for some other publishers despite the Nintendo onslaught. (The line included a submarine simulator, an elaborate CRPG, etc.) They also started a line of personal-creativity software similar to Electronic Arts’s “Deluxe” line, and began importing ever more European action games to sell as budget titles to low-end customers. All told, their total revenues for 1988 actually increased robustly over that of the year before, from $27 million to $36 million. Yet such figures can be deceiving. Because this total was generated from many more products, with all the extra expenses that implied, the ultimate arbiter of net profits on computer software plunged instead of rising commensurately. Other ventures were truly misguided by any standard. Like a number of other publishers, Epyx launched forays into the interactive VCR-based systems that were briefly all the rage as substitutes for Philips’s long-promised but still undelivered CD-I system. They might as well have just set fire to that money. The Epyx of earlier years had had a recognizable identity, which the Epyx of 1988 had somehow lost. There was no thematic glue binding their latest products together.

Meanwhile Epyx was investing hugely in games for the Potato — investing just about as much money in Potato software, in fact, as they were pouring into the hardware. Accounts of just how much the Potato’s development ended up costing Epyx vary, ranging from $4 million to $8 million and up. I suspect that, when viewed in terms of both hardware and software development, the figure quite likely skews into the double digits.

Whatever the exact numbers, as the curtain came up on 1989 Dave Morse, RJ Mical, and Dave Needle found themselves in a position all too familiar from the old days with Amiga, Incorporated. They had another nascent revolution in silicon in the form of the Potato, which had reached the prototype stage and was to be publicly known as the Epyx Handy. Yet their company’s finances were hopelessly askew. If the Handy was to become an actual product, it looked like Morse would need to pull off another miracle.

So, he did what he had done for the Amiga Lorraine. In a tiny private auditorium behind Epyx’s public booth at the January 1989 Winter Consumer Electronics Show, the inventors of the Handy showed it off to a select group of representatives from other companies, all of whom were required to sign a strict non-disclosure agreement before seeing what was still officially a top-secret project, even though rumors of the Handy’s existence had been spreading like wildfire for months now. The objective was to find a partner to help manufacture and market the Handy — or, perhaps better, a buyer for the entire troubled company. Nintendo had a look, but passed; they had a handheld console of their own in the works which would emerge later in the year as the Nintendo Game Boy. Sega also passed. In fact, just about everyone passed, as they had on the Amiga Lorraine, until Morse was left with just one suitor. And, incredibly, it was the very same suitor as last time: Atari. Déjà vu all over again.

On the positive side, this Atari was a very different company from the 800-pound gorilla that had tried to seize the Lorraine and carve it up into its component parts five years before. On the negative, this Atari was run by Jack Tramiel, Mr. “Business is War” himself, the man who had tied up Commodore in court for years after Atari’s would-be acquisition of the Amiga Lorraine had become Commodore’s. From Tramiel’s perspective, getting a stake in a potential winner like the Handy made a lot of sense; his Atari really didn’t have that much going for it at all at that point beyond a fairly robust market for their ST line in Europe and an ongoing trickle of nostalgia-fueled sales of their vintage game consoles in North America. Atari had missed out almost entirely on the great second wave of videogame consoles, losing the market they had once owned to Nintendo and Sega. If mobile gaming was destined to be the next big thing, this was the perfect way to get into that space without having to invest money Atari didn’t have into research and development.

For his part, Morse certainly knew even as he pulled the trigger on the deal that he was getting into bed with the most devious man in consumer electronics, but he didn’t see that he had much choice. He could only shoot from the hip, as he had five years before, and hope it would all work out in the end. The deal he struck from a position of extreme weakness — nobody could smell blood in the water quite like Jack Tramiel — would see the Handy become an Atari product in the eyes of the marketplace. Atari would buy the Handy hardware design from Epyx, put their logo on it, and would take over responsibility for its manufacturing, distribution, and marketing. Epyx would remain the “software partner” only, responsible for delivering an initial suite of launch titles and a steady stream of desirable games thereafter. No one at Epyx was thrilled at the prospect of giving away their baby this way, but, again, the situation was what it was.

At this point in our history, it becomes my sad duty as your historian to acknowledge that I simply don’t know precisely what went down next between Atari and Epyx. The source I’ve been able to find that dates closest to the events in question is the “Roomers” column of the December 1989 issue of the magazine Amazing Computing. According to it, the deal was structured at Tramiel’s demand as a series of ongoing milestone payments from Atari to Epyx as the latter met their obligations to deliver to the former the finished Handy in production-ready form. Epyx, the column claims, was unable to deliver the cable used for linking two Handys together for play in the time frame specified in the contract, whereupon Atari cancelled a desperately needed $2 million payment as well as all the ones that were to follow. The Handy, Atari said, was now theirs thanks to Epyx’s breach of contract; Epyx would just have to wait for the royalties on the Handy games they were still under contract to deliver to get more money out of Atari. In no condition to engage Atari in a protracted legal battle, Epyx felt they had no choice but to concede and continue to play along with the company that had just stolen their proudest achievement from them.

Dave Needle, who admittedly had plenty of axes to grind with Atari, told a slight variation of this tale many years later, saying that the crisis hinged on Epyx’s software rather than hardware efforts. It seems that Epyx had sixty days to fix any bugs that were discovered after the initial delivery of each game to Atari. But, according to Needle, “Atari routinely waited until the end of the time period to comment on the Epyx fixes. There was then inadequate time for Epyx to make the fixes.” Within a few months of inking the deal, Atari used a petty violation like this to withhold payment from Epyx, who, of course, needed that money now. At last, Atari offered them a classic Jack Tramiel ultimatum: accept one more lump-sum payout — Needle didn’t reveal the amount — or die on the vine.

A music programmer who went by the name of “Lx Rudis” is perhaps the closest thing to an unbiased source we can hope to find; he worked for Epyx while the Handy was under development, then accepted a job with Atari, where he says he was “close” with Jack Tramiel’s sons Sam and Leonard, both of whom played important roles within their father’s company. “The terms [of the contract] were quite strict,” he says. “Epyx was unable to meet all points, and Atari was able to withhold a desperately needed milestone payment. In the chaos that ensued, everyone got laid off and I guess Atari’s lawyers and Epyx’s lawyers worked out a ‘compromise’ where Atari got the Handy.”

No smoking gun in the form of any actual paperwork has ever surfaced to my knowledge, leaving us with only anecdotal accounts like these from people who weren’t the ones signing the contracts and making the deals. What we do know is that Epyx by the end of 1989 was bankrupt, while Atari owned the Handy outright — or at least acted as if they did. Although it’s possible that Tramiel was guilty of nothing more than driving a hard bargain, his well-earned reputation as a dirty dealer does make it rather difficult to give him the benefit of too much doubt. Certainly lots of people at Epyx were left feeling very ill-served indeed. Dave Morse had tried to tweak the tiger’s tail a second time, and this time he had gotten mauled. As should have been part of the core curriculum at every business school by this point: don’t sign any deal, ever, with Jack Tramiel.

Dave Morse, RJ Mical and Dave Needle walked away from the whole affair disgusted and disillusioned, having seen their baby kidnapped by the man they had come to regard as Evil incarnated in an ill-fitting pinstriped suit. Their one bitter consolation was that the Handy development system they’d built could run only on an Amiga. Thus Atari would have to buy dozens of specimens of the arch-rival platform for internal use, and suffer the indignity of telling their development licensees that they too would need to buy Amigas to make their games. It wasn’t much, but, hey, at least it was something to hold onto.

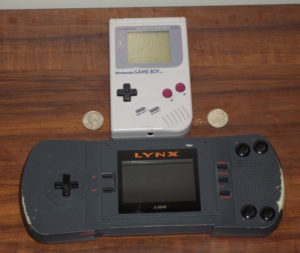

The erstwhile Epyx Handy made its public debut at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1989 as the Atari Portable Entertainment System. But when someone pointed out that that name would inevitably get abbreviated to “APES,” Atari moved on from it, finally settling on the name of “Lynx,” a sly reference to the ability to link the machines together via cable for multiplayer action. Thus christened, the handheld console shipped on September 1, 1989. Recent unpleasantness aside, Mical and Needle had good cause to be proud of their work. One far-seeing Atari executive said that the Lynx had the potential to become a revolutionary hit on the level of the Sony Walkman of 1979, the product which largely created the idea of personal portable electronics as we think of them today. Now it was up to Atari to realize that potential.

That part of the equation, alas, didn’t go as well as Atari had hoped. Just one month before the Lynx, Nintendo of America had released the Game Boy, their own handheld console. Purely as a piece of kit, the black-and-white-only Game Boy wasn’t a patch on the Lynx. But then, Nintendo has always thrived by transcending technical specifications, and the Game Boy proved no exception to that rule. Like all of their products, it was laser-targeted to the needs and desires of the burgeoning Generation Nintendo, with a price tag of just $90, battery life long enough to get you through an entire school week of illicit playing under the desk, a size small enough to slip into a coat pocket, and a selection of well-honed launch games designed to maximize its strengths. Best of all, every Game Boy came bundled with a copy of Tetris, an insanely addictive little puzzle game that became a veritable worldwide obsession, the urtext of casual mobile gaming as we’ve come to know it today; many a child’s shiny new Game Boy ended up being monopolized by a Tetris-addled parent.

The Lynx, by contrast, was twice as expensive as the Game Boy, ate its AA batteries at a prodigious rate, was bigger and chunkier than the Game Boy, and offered just three less-than-stellar games to buy beyond the rather brilliant Epyx port of California Games that came included in the box. Weirdly, its overall fit and finish also lagged far behind the cheap but rugged little Game Boy. Atari struggled mightily to find suppliers who could deliver the Lynx’s components on time and on budget with acceptable quality control. According to RJ Mical — again, not the most unbiased of sources — this was largely a case of Jack Tramiel’s chickens coming home to roost. “The new ownership of the Lynx had really bad reputations with hardware manufacturers in Asia and with software developers all over the world,” says Mical. “Suddenly all those sweet deals we’d made for low-cost parts for the Lynx dried up on them. They’d be like, ‘We remember you from five years ago. Guess what — the price just doubled!'” Mical claims that a “magnificent library” of Lynx games, the result of many deals Epyx had made with outside developers, fell by the wayside as soon as the developers in question learned that they’d have to deal from now on with Jack Tramiel instead of Dave Morse.

In the face of these disadvantages, the Lynx wasn’t the complete failure one could so easily imagine it becoming. It remained in production for more than five years, over the course of which it sold nearly 3 million units to buyers who wanted a little more from their mobile games than what the Game Boy could offer. By most measures, the Atari Lynx was a fairly successful product. It suffers only by comparison with the Game Boy, which spent an astonishing total of almost fifteen years in production and sold an even more astonishing 118.69 million units, becoming in the process Nintendo’s biggest single success story of all; in the end, Nintendo sold nearly twice as many Game Boys as they did of the original Nintendo Entertainment System that had done such a number on Epyx’s software business. So, a handheld game console did become worthy of mention in the same breath as the Sony Walkman, but it wasn’t the Atari Lynx; it was the Nintendo Game Boy.

Needless to say, Dave Morse’s old plan to make Epyx a $100 million company by 1990 didn’t come to fruition. In addition to all their travails with Atari, the Commodore 64 market, the old heart of their strength, had imploded like a pricked balloon. After peaking at 145 employees in 1988, when work on the Handy as well as games for it was buzzing, frantic layoffs brought Epyx’s total down to less than 20 by the end of 1989, at which point the firm, vowing to soldier on in spite of it all, went through a Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Just to add insult to the mortal injury Jack Tramiel had done them, they came out of the bankruptcy still under contract to deliver games for the Lynx. Indeed, doing so offered their only realistic hope of survival, slim though it was, and so they told the world they were through developing for computers and turned what meager resources they had left entirely to the Lynx. They wouldn’t even be a publisher in their own right anymore, relying instead on Atari to sell and distribute their games for them. Tramiel had, as the kids say today, thoroughly pwned them.

This zombie version of Epyx shambled on for a disconcertingly long time, plotting always for ways to become relevant to someone again without ever quite managing it. It finally lay down for the last time in 1993, when the remnants of the company were bought up by Bridgestone Media Group, a Christian advocacy organization with ties to one of Epyx’s few remaining employees. By this time, the real “end of the Epyx era,” as Computer Gaming World editor Johnny Wilson put it, had come long ago. In 1993, the name “Epyx” felt as much like an anachronism as the Commodore 64.

What, then, shall we say in closing about Epyx? If Cinemaware, the subject of my last article, was the prototypical Amiga developer, Epyx has a solid claim to the same title in the case of the Commodore 64. As with Cinemaware, manifold and multifarious mistakes were made at Epyx that led directly to the company’s death, mistakes so obvious in hindsight that there seems little point in belaboring them any further here. (Don’t try to design, manufacture, and launch an entirely new gaming platform if you don’t have deep pockets and a rock-solid revenue stream, kids!) They bit off far more than they could chew with the Handy. Combined with their failure to create a coherent identity for themselves in the post-Commodore 64 computer-games industry, it spelled their undoing.

And yet, earnest autopsying aside, when all is said and done it does feel somehow appropriate that Epyx should have for all intents and purposes died along with their favored platform. For a generation of teenage boys, the Epyx years were those between 1984 and 1988, corresponding with the four or five dominant years which the Commodore 64 enjoyed as the most popular gaming platform in North America. It seems safe to say that as long as any of that generation remain on the planet, the name of Epyx will always bring back memories of halcyon summer days of yore spent gathered with mates around the television, joysticks in hand. Summer Games indeed.

(Sources: Questbusters of November 1989; ACE of May 1990; Retro Gamer 18 and 129; Commodore Magazine of July 1988 and August 1989; Small Business Report of February 1988; San Francisco Business Times of July 25 1988; Amazing Computing of June 1988, November 1988, March 1989, April 1989, June 1989, August 1989, November 1989, December 1989, January 1990, and February 1990; Info of November/December 1989; Games Machine of March 1989 and January 1990; Compute!’s Gazette of April 1988; Compute! of November 1987 and September 1988; Computer Gaming World of November 1989, December 1989, and November 1991; Electronic Gaming Monthly of September 1989. Online sources include articles on US Gamer, Now Gamer, Wired, and The Atari Times. My huge thanks to Alex Smith, who shared his take on Epyx’s collapse with me along with some of the sources listed above.)