The microcomputer had a well-nigh revolutionary impact on the way that business was done over the first twenty years after its invention: the arrival of a computer on every desk made the workplace more efficient in countless ways. But the gadget’s impact on our personal lives during this period was less all-encompassing. Yes, many youngsters and adults learned the advantages of word processing over typewriting, and a substantial minority of both learned the advantages of computer over console gaming. Meanwhile smaller minorities learned of the pleasures of programming, and some even ventured online to meet others of their ilk. Yet the wide-angle social transformation promised by the most starry-eyed pundits during the would-be Home Computer Revolution of the early 1980s didn’t materialize on the timetable we were promised. For a good decade after the heyday of such predictions, one could get on perfectly well as an informed, aware, plugged-in member of society without owning a computer or caring a whit about them. The question of what a home computer was really good for, beyond word processing, entertainment, and accessing fairly primitive online services at usually exorbitant prices, was difficult to answer for the average person. Most of the other usage scenarios proposed during the early 1980s, from storing recipes to balancing one’s checkbook, remained easier and cheaper on the whole to do the old-fashioned way. The personal computer seemed a useful invention in its realm, to be sure, but not a society-reshaping one.

All of that changed in the mid-1990s, when the Internet entered the public consciousness. By the turn of the millennium, those unable or unwilling to buy a computer and enter cyberspace were well and truly left behind, having no seat at the table where our most important cultural dialogs were suddenly taking place. It’s almost impossible to exaggerate the impact the Internet has had on us: on the way we access information, on the way we communicate and socialize with one another, on the way we entertain ourselves, on the very way we think. The claim that the Internet is the most important advance in the technologies of information and communication since Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, which once seemed so expansive, now seems almost picayune in relation to the change we’ve witnessed. Coming at the end of a century of wondrous inventions, the Internet was the most wondrous of them all. We may still be waiting for our flying cars and cheap tickets to Mars, but the world we live in today would nevertheless have seemed thoroughly science-fictional just 30 years ago. Seen in this light, the computer itself seems merely a comparatively plebeian bit of infrastructure that needed to be laid down for the really earth-shattering technology to build upon. Or perhaps we were just seeing computers the wrong way before the Internet: what seemed most significant as a tool for, well, computation was actually a revolution in communication just waiting to happen. In this formulation, a computer without the Internet is like a car without any roads.

When I talk about the Internet in this context, of course, I really mean the combination of a globe-spanning network of computers — one which was already a couple of decades old by the beginning of the 1990s — with the much younger World Wide Web, which applied to the network a new paradigm of effortless navigation based on associative hyperlinks. This serves as a useful reminder that no human invention since the first stone tools has ever been monolithic; inventions are always amalgamations of existing technologies, iterations on what came before. In A Brief History of the Future, his classic millennial history of and philosophical meditation on the Internet, John Naughton noted that “it’s always earlier than you think. Whenever you go looking for the origins of any significant technological development, you find that the more you learn about it, the deeper its roots seem to tunnel into the past.”

I thought about those words a lot as I considered how best to tell the story of the Internet and the World Wide Web here. And as I did so, I kept coming back to this word “Web.” In the strict terms by which Tim Berners-Lee meant the word when he invented the World Wide Web, it refers to a logical web of links. But the prerequisite for that logical web is the physical web of cables that allows computers to talk to one another over long distances in the first place. This infrastructure was not originally designed for computers; it is in fact much, much older than they are. Still, this network — the physical network — strikes me as the most logical place to start this series of articles about the Internet, that ultimate expression of instantaneous worldwide communication.

Aeschylus’s tragedy Agamemnon of the fifth century BC deals, like so much classical Greek literature, with the Trojan War, an event historians now believe to have occurred in approximately 1000 BC. In the play, we’re told how the Greek soldiers abroad sent news of their victory over the Trojans back to their homeland far more quickly than any ship- or horse-borne messenger could possibly have delivered it. This ecstatic paean to modern communication issues from the mouth of Clytemnestra, the wife of the Greek commander Agamemnon, who has been waiting on her husband for ten years at home in the Peloponnesian city of Argos:

Hephaestus, who sent the blazing light from Ida;

then beacon after beacon’s courier flame:

from Ida first, to Hermes’ crag at Lemnos.

Third came the Athos summit, which belongs

to Zeus: it, too, received the massive firebrand.

Ascending now to shoot across the sea’s back,

the journeying torch in all its power and joy.

The pine wood, like a second sun, conveyed

the gold-gleam to the watchtower on Macistus.

Prompt and triumphant over feckless sleep,

unslacking in its task as courier,

passing Euripus’s streams, the beacon’s light

signaled far off to watchmen on Messapion.

They sent out light in turn, sent on the message,

setting alight a rick of graying heather.

Potent against the dimming murk, the light

went leaping high across Asopus’ plain

like the beaming moon, and at Cathaeron’s scarp

roused missive fire still another relay.

The lookout there did not defy the light

sent from far off; the new blaze shot up stronger.

The glow shot past the lake called Gorgon’s Face;

arriving at the mountains where the goats roam,

it urged the fire-ordnance on.

With all their strength, men raised a giant flame,

beard-shaped, to overshoot and pass beyond

the headland fronting the Saronic strait —

so bright the blaze. Darting again, it reached

Arachne’s lookout peak, this city’s neighbor;

then it fell here, on the Atreides’ mansion.

The light we see descends from Ida’s fire.

Tourchbearers served me in this regimen,

with every handoff perfectly performed.

The runners who came first and last both win.

This is my proof, the pledge of what I tell you.

My husband passed the news to me from Troy.

In this fascinating passage, then, we learn of what may have been the first near-instantaneous long-distance communications network ever conceived, dating back more than 3000 years. The signal began with a burning pyre atop Mount Ida near Troy itself, then flashed onward like a torch being passed between the members of a relay team: to the highlands of the island of Lemnos, to Mount Athos on a northeastern peninsula of the Greek mainland, to the northern tip of the island of Euboea, to finally reach the mainland city of Aulas, whence the Greek fleet had sailed for Troy so long before. From there, the signal fires spread across Greece. Historians and geographers are skeptical whether such a signal system might truly have been practicable, even given the mountainous landscape of the region with its many rarefied peaks. But even if it never existed in reality, Aeschylus — or some other, anonymous earlier Greek who created the legend before him — deserves a great deal of credit for imagining that such a thing might exist.

Others after Aeschylus refined the idea further, into something that would function over shorter distances in places without mountain peaks in useful proximity to one another, something that might be used to send a message at least slightly more complicated than word of a war won. During the Second Punic War of the late second century BC, both Rome and its enemy Carthage are believed to have built networks of signal towers for purposes of battlefield communication. Very simple messages — signals to attack or withdraw, etc. — could be passed from tower to tower by waving torches in distinctive patterns. Many more short-range optical-signal systems followed: the Chinese used fireworks on their border walls to raise the alarm if one section was attacked by the “barbarians” on the other side; harbors raised flags to inform ships of the height and movement of the tides.

But all such systems were sharply limited in the types of information they could transmit and the distances over which they could send it. On any broader, more flexible scale, the speed of communication was still the same as that of messengers on horseback, or of sailors in ships at the mercy of the wind and waves. The impact this had on commerce, on diplomacy, and on warfare is difficult for us children of the mass-media age to appreciate; there are repeated instances in history of such follies as bloody battles fought after the wars that spawned them had already ended, because word of the ceasefire couldn’t be gotten to the front lines in time. The people of the past, for their part, had equally little conception of any alternative speed of communication; for them, the weeks that were required to, say, get a message from the Americas to Europe were as natural as a transatlantic telephone call is to us.

But in 1789, one Claude Chappe, a French seminary student whose studies had been interrupted by his country’s political revolution, began to envision something else. He became obsessed with the idea of a fast long-range communications network that could transmit messages as arbitrary as the content of any given written letter. He first thought of using electricity, a phenomenon which scientists and inventors were just starting to consider how to turn to practical purposes. But it was still a dangerous, untamed beast at this juncture, and Chappe quickly — and probably wisely — set it aside. Next he turned to sound. He and his four brothers discovered that a cast-iron pot could be heard up to a quarter of a mile away if hit hard enough with a steel mallet. Thus by beating out patterns they could pass messages across reasonably long distances, a quarter-mile at a time. But the method had some obvious problems: its range was highly dependent on the vagaries of wind and weather, and the brothers’ experiments certainly didn’t make them very popular with their neighbors. So, Chappe went back to the drawing board again — went back, in fact, to the ancient solution of optical signalling.

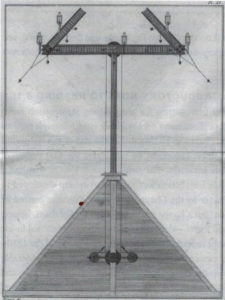

After much experimentation, he arrived at a system based on semaphores mounted atop towers. Each semaphore consisted of three separate, jointed pieces which could be positioned in multiple ways, enough so that there were fully 98 possible distinct configurations of the apparatus as a whole. Six of the configurations were reserved for special purposes, the equivalent of what a digital-network engineer would call “control blocks”: stop and start signals, requests for re-transmission, etc. The other 92 stood for numbers. Chappe provided a code dictionary consisting of 8464 words, divided into 92 pages of 92 words each. The transmission of each word was a two-step procedure: first a number pointing to the page, then another pointing to the word on that page. The system even boasted a form of error correction: since the operator of the next tower in the chain would need to configure his semaphores to match those of the tower before his in order to transmit the message further, the operator in the previous tower got a chance to confirm that his message had been received correctly, and was expected to send a hasty “Belay that!” signal in the case of a mistake.

Optical engineering had by now progressed to the point that Chappe’s towers could be placed much farther apart than any of the signal towers of old, for they could now be viewed through a telescope rather than with the naked eye. Chappe envisioned a vast network of towers, separated from one another by 10 to 20 miles (15 to 30 kilometers) depending on the terrain, the whole extending across the country of France or even eventually across the whole continent of Europe.

The system was labor-intensive, requiring as it did a pair of attendants in every tower. It was also slow — at best, it was good for about one word per minute — and at the mercy of the hours of daylight and to some extent the weather. But when the conditions were right it worked. Appropriately given how the germ of the concept stemmed from Aeschylus, Chappe turned to Greek for a name for his invention. He first wanted to call it the tachygraphe, combining two Greek cognates meaning “fast” and “writing.” But a friend in the government suggested télégraphe — “distant writing” — instead.

Living in revolutionary times tends to bring challenges along with benefits: Chappe and his brothers had to run for their lives during at least one of their tests, when a mob decided they must be Royalist sympathizers passing secret messages of sedition. On the other hand, the new leaders of France were as eager as any have ever been to throw out the old ways of doing things and to embrace modernity in all its aspects. Some of the innovations they enacted, such as the metric system of measurement, have remained with us to this day; others, such as a new calendar that used ten-day weeks (Revolutionary France had a positive mania for decimals), would prove less enduring. Chappe’s telegraph would fall somewhere in between the two extremes, adding a word and an idea to our culture that would long outlive this first practical implementation of it.

On July 26, 1793, following a series of proof-of-concept demonstrations, the National Convention gave Claude Chappe the title of “Telegraph Engineer” in the Committee of Public Safety. And so, while other branches of the same Committee were carrying out the Reign of Terror with the assistance of Madame la Guillotine, Chappe was building a chain of signal towers stretching from Lille to Paris; the terminus in the capital stood on the dome of the Louvre Palace, newly re-purposed as a public art museum.

On August 15, 1794, shortly after the telegraph went officially into service, it brought news of a major French victory in the war with the old, conservative order of Europe that was going on on the country’s northern border. A National Convention delegate named Lazare Carnot ascended to the podium in the Salles des Machines in Paris. “Quesnoy is restored to the Republic,” he read out from the scrap of paper in his hands. “Its surrender took place at six o’clock this morning.” A wave of jubilation swept the hall, prompted not only by the military victory thus reported but by the timeliness with which the news had arrived, which seemed an equally potent validation of the whole forward-looking revolutionary project. A delegate to the Convention named Joseph Lakanal summed up the mood: “What brilliant destiny do science and the arts not reserve to a republic which, by the genius of its inhabitants, is called to instruct the nations of Europe!”

In the end, the republic in question had a shorter career than Lakanal might have hoped for it, but Chappe’s telegraph survived its demise. By the time Napoleon seized power from the corrupt and dysfunctional remnants of the Revolution in 1799, most of France had been bound together in a web of towers and semaphores. Napoleon supported the construction of many more stations as part of his mission to make France the world’s unrivaled leader in science and technology. But Chappe found himself increasingly sidelined by the French bureaucracy, even as he apparently suffered from a debilitating bladder disease. On January 25, 1805, at the age of 42, he either cut his own throat while standing beneath a telegraph tower on the Rue de Saint Germain in Paris, or deliberately threw himself into a well, or stumbled accidentally into one. (Reports of the death of Claude Chappe, like many of those pertaining to his life, are confused and contradictory, a byproduct of the chaotic times in which he lived.)

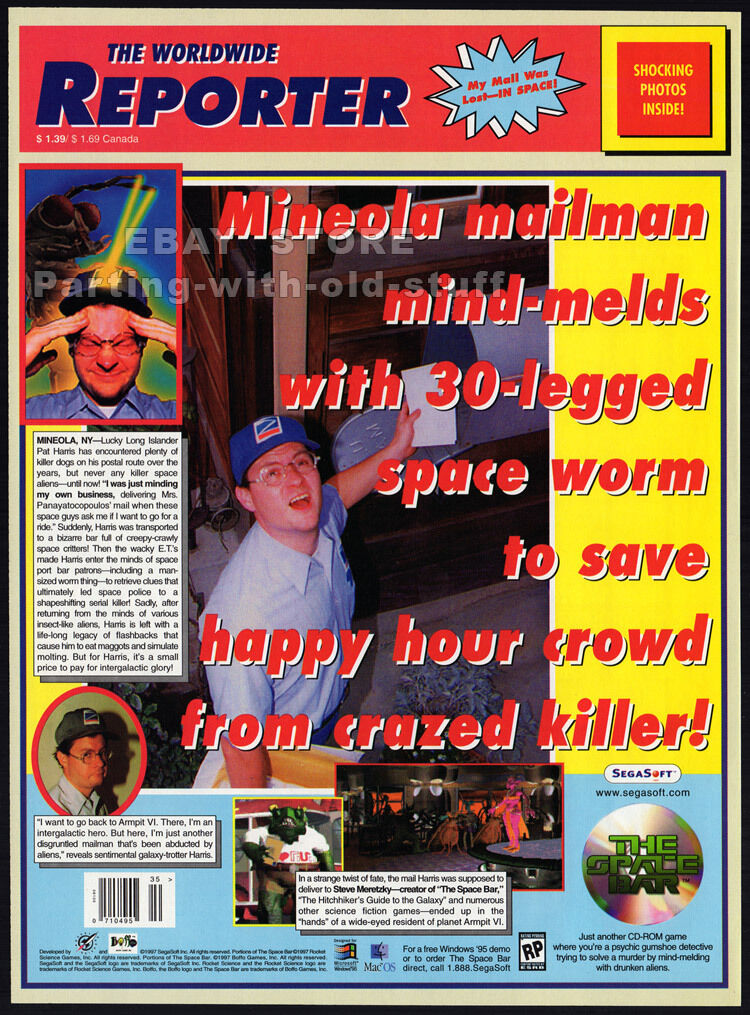

This statue of Claude Chappe used to stand in central Paris on the site where some say he committed suicide, just next to one of his preserved telegraph towers. It was removed and melted down by the Nazis during World War II.

His optical telegraph would live on for another half-century after him, growing to fully 556 towers, concentrated in France but stretching as far as Amsterdam, Brussels, Mainz, Milan, Turin, and Venice. According to folk history, it was used for the last time in 1855, to bring news of the victory of France and its allies in the siege of Sevastopol — a fitting bookend for a system which had announced its arrival with word of another military victory more than 60 years before.

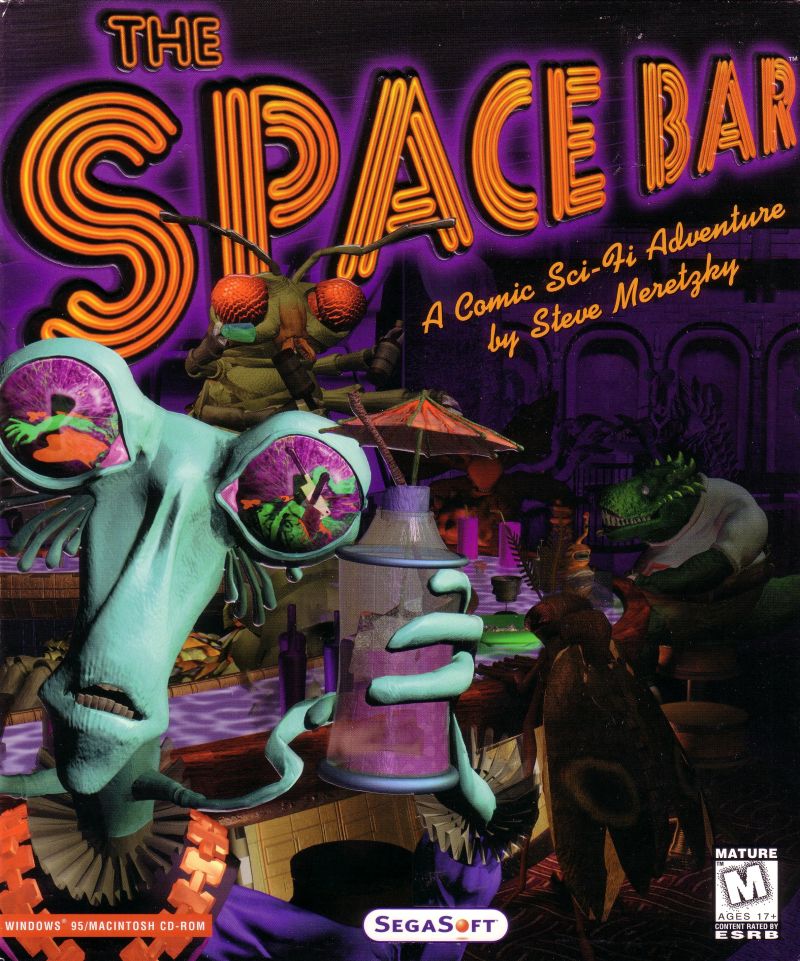

Remnants of Chappe’s telegraph network can still be seen in many places in France. This semaphore tower stands in the commune of Saverne in the northeastern part of the country.

One morning he made him a slender wire,

As an artist’s vision took life and form,

While he drew from heaven the strange, fierce fire

That reddens the edge of the midnight storm;

And he carried it over the Mountain’s crest,

And dropped it into the Ocean’s breast;

And Science proclaimed, from shore to shore,

That Time and Space ruled man no more.

“We are one!” said the nations, and hand met hand,

In a thrill electric from land to land.— “The Victory,” written anonymously in honor of Samuel Morse upon his death in 1872

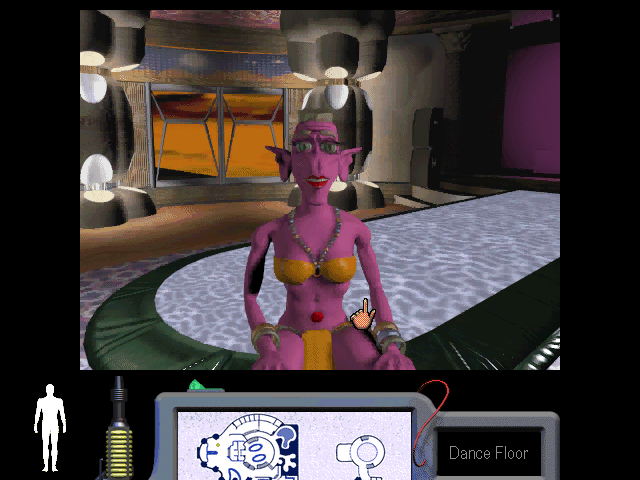

This photograph of Samuel Morse was taken in 1840, in the midst of his struggle to interest the world in his electric telegraph.

In 1824, a 33-year-old American painter named Samuel Morse traveled to Washington, D.C. An artist of real talent with a not unimpressive track record — he had once been commissioned to paint President James Monroe — he had previously been in the habit of prioritizing his muse over his earnings. But now he was determined to change that: he went to the capital in the hope of becoming one of a small circle of painters who earned a steady living by making flattering official portraits of prominent men.

On February 10, 1825, Morse sent a letter back home to his wife in New Haven, Connecticut, with some exciting news: he had won a lucrative contract to paint the Marquis de Lafayette, a famous hero of both the American and French Revolutions. But his wife never got to read the letter: she had died on February 7. The day after Morse had posted his missive, word of her death finally reached him. He immediately left for home, but by the time he arrived she had already been buried. The episode was a painful lesson in the shortcomings of current communications methods in the United States, a country which had not embraced even the optical telegraph.

In addition to his more well-known accomplishments as an inventor, Samuel Morse was a painter of no small talent and not inconsiderable importance. He painted his rather magnificent Grand Gallery of the Louvre on his trip to Europe of 1829 to 1832.

Seven years later, Morse found himself aboard a packet ship called the Sully, returning to his homeland from France after an extended sojourn in Europe during which he had combined the profitable business of making miniature copies of European masterpieces with the more artistically satisfying one of trying to create new masterpieces of his own. One of his fellow passengers enjoyed dabbling with electricity, and showed him a battery and some other toys he had brought onboard. Morse was not, as is sometimes claimed, a complete neophyte to the wonders of electricity at this point; a man of astonishingly diverse interests and aptitudes, he had attended a series of lectures on the subject a few years earlier, and had even befriended the instructor. Nevertheless, he clearly had a eureka moment aboard the Sully. “It occurred to me,” he would later write, “that by means of electricity, signs representing figures, letters, or words might be legibly written down [emphasis original] at any distance.” He chattered almost manically about it to anyone who would listen throughout the four-week passage home. His brother Sidney, who met him at the dock upon the Sully‘s arrival in New York City, would later recall that he was still “full of the subject of the [electric] telegraph during the walk from the ship, and for some days afterward could scarcely speak about anything else.”

His surprise and excitement at the thought were in some ways a measure of his ignorance: the idea of an electric telegraph that would not be subject to all of the multitudinous drawbacks of optical systems was practically old hat by now in engineering and invention circles. Still, no one had ever quite managed to get one to work well enough to be useful. This may strike us as odd today; as Tom Standage has noted in his book The Victorian Internet, any clever child of today can construct a working one-way electric telegraph in the course of an afternoon. All you need is a length of wire, a breaker switch, an electric lamp of some sort, and a battery. Run the wire between the breaker switch and the lamp, connect the whole circuit to the battery, and you can sit at one end of the wire making the bulb at the other end flash on and off to your heart’s content. All that’s left to do is to decide upon some sort of code to give meaning to the flashes.

But for electrical experimenters at the turn of the nineteenth century, the devil was in the details. One serious problem was that of detecting the presence or absence of electric current at all, many decades before reasonably reliable incandescent light bulbs became available. By 1800, it had been discovered that immersing the end of a live wire into water would generate telltale bubbles; we now understand that these are the result of a process known as electrolysis, in which an electric current breaks water molecules down into their component hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Experiments were conducted which attempted to apply this phenomenon to telegraphy, but it was difficult, to say the least, to read a coherent message from bubbles floating in a pot of water.

A breakthrough came in 1820, when a Danish scientist named Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric current pulls the needle of a compass toward itself. Electricity, in other words, generates its own magnetic field. By winding together a coil of wire, one can make an electromagnet, which affects a compass or anything else containing ferromagnetic materials just like an ordinary magnet, with one important difference: this magnet functions only when electric current is flowing through the coil. The implications for telegraphy were enormous: an electromagnet should finally make it possible to instantly and precisely detect the presence or absence of current in a wire.

But there was still another problem: it didn’t seem to be possible to transmit currents over really long wires. Over such distances as those which separated two typical towers in Claude Chappe’s optical-telegraph system — much less that which separated, say, Lille from Paris — the signal just seemed to peter out and disappear. In 1825, a Briton named Peter Barlow, one of the eminent mathematical and scientific luminaries of his day, conducted a series of experiments to determine the scale of the problem. His conclusions gave little room for optimism. A current’s strength on a wire, he wrote, was inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the battery that had spawned it. As for the telegraph: “I found such a sensible diminution with only 200 feet [60 meters] of wire as at once to convince me of the impracticality of the scheme.”

Luckily for the world, not everyone was ready to defer to Barlow’s reputation. An American named Joseph Henry, a teacher of teenage boys at The Albany Academy in New York who was possessed at the time of neither a university degree nor an international reputation, conducted experiments of his own, and found that Barlow had been mistaken in one of his key conclusions: he found that the strength of a current was inversely proportional to its distance from the battery, full stop — i.e., not from the distance squared. In the course of further experimenting, Henry discovered that higher voltages lost proportionally even less of their strength over distance than weaker ones. Fortunately, the state of the art in batteries was steadily improving. Henry found that a cutting-edge 25-cell battery had enough “projectile force” to push a current a fairly long distance; it was able to ring a bell at the end of a wire more than a mile (1.6 kilometers) long. He published his findings in 1831, while a blissfully unaware Samuel Morse was painting pictures in Europe. But the world of science and invention did take notice; suddenly a workable electric telegraph seemed like a practical possibility once again.

Meanwhile Morse spent the years after his eureka moment aboard the Sully as busily and diversely as ever: teaching art at New York University, teaching private pupils how to paint, painting more pictures of his own, serving on the American Academy of Fine Arts, writing feverish anti-Catholic screeds, even running for mayor of New York City under the auspices of the anti-immigration Native American Democratic Association. (Like too many men of his era, Morse was a thoroughgoing racist and bigot in addition to his more positive qualities.) In light of all this activity, it would be a stretch to say he was consistently consumed with the possibility of an electric telegraph, but he clearly did tinker with the project intermittently, and may very well have followed the latest advancements in the field of electrical transmission closely as part of his interest.

But while people like Joseph Henry were asking whether and how an electrical signal might be sent over a long distance in the abstract, Morse was asking how an electric telegraph might actually function as a tool. How could you get messages into it, and how could you get them out of it?

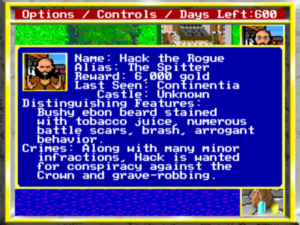

Morse’s first solution to the problem of sending a message is a classic example of how old paradigms of thought can be hard to escape when inventing brand-new technology. He designed his electric telegraph to work essentially like a long-distance printing press. The operator arranged along a groove cut into a three-foot (1-meter) beam of wood small pieces of metal “movable type,” each having from one to ten teeth cut into it to represent a single-digit number; ten teeth meant zero. He then slotted the beam into a sending apparatus Morse called a “port-rule,” attached to one end of the telegraph wire. The operator turned a hand crank on the port-rule’s side to move the beam through the contraption. As he did so, the teeth on the metal type caused a breaker connected to the telegraph wire to close and open, producing a pattern of electrical pulses.

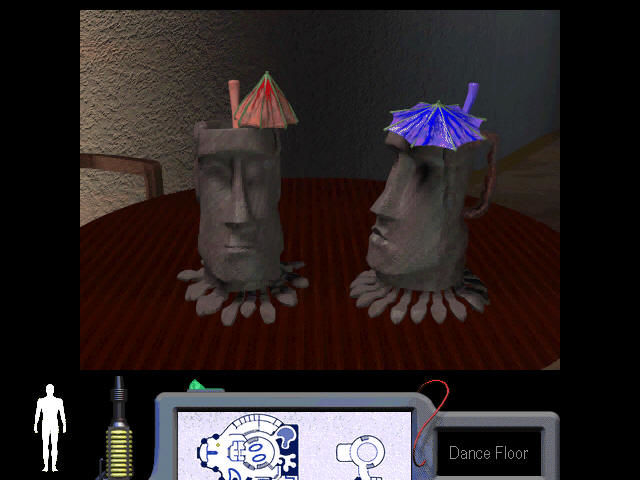

Morse’s movable type. We see here two pieces representing the number two, and one representing each of three, four, and five.

At the other end of the wire was an electromagnet, to which was mounted a pencil on the end of a spring-loaded arm made from a ferromagnetic metal. The nib of the pencil rested on a band of paper, which could be set in motion by means of a clockwork mechanism driven by a counterweight. When a message came down the wire, the electrical pulses caused the electromagnet to switch on and off, pulling the pencil up and down as the paper scrolled beneath it. The resulting pattern on the paper could then be translated into a series of digits, which could then be further decoded into readable text using a code dictionary not dissimilar to the one employed by Claude Chappe’s optical telegraph.

It was all quite fiddly and complicated, but by 1837 — i.e., fully five years after Morse’s eureka moment — it more or less worked on a good day. Range was his biggest problem; not having access to the cutting-edge batteries that were available to Joseph Henry, Morse found that his first versions of his telegraph could only transmit a message 40 feet (12 meters). Pondering this, he came up with a rather brilliant stopgap solution, in the form of what is now called a “repeater”: an additional battery partway down the wire, activated by an electromagnet that responded to the current coming down the prior section of wire. “By the same operation the same results may again be repeated,” Morse wrote in his patent application, “extending and breaking at pleasure such current through yet another and another circuit, ad infinitum.” If you had enough batteries and electromagnets, in other words, you could extend the telegraph to a theoretically infinite length.

With his invention looking more and more promising, Morse befriended a younger man named Alfred Vail, the scion of a wealthy family with many industrial and political connections. Vail became an important collaborator in ironing out the design of the telegraph, while his family signed on as backers, giving Morse access to much more advanced batteries among other benefits. In January of 1838, he sent a “pretty full letter” down a wire 10 miles (16 kilometers) long. “The success is complete,” he exalted.

“Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to rest it, and I will move the world,” the ancient engineer Archimedes had once (apocryphally) said. Now, Morse paraphrased him with an aphorism of his own: “If [the signal] will go ten miles without stopping, I can make it go around the globe.”

One month after their ten-mile success, Morse and Alfred Vail traveled to Washington, D.C., to demonstrate the telegraph to members of Congress and even to President Martin Van Buren himself. The demonstration was not a success; it’s doubtful whether most of the audience, the president among them, really understood what they were being shown at all. This was not least because Morse was forced to set up his sending and receiving stations right next to one another in the same room, then to try to explain that the unruly tangle of wire lying piled up between them meant that they could just as well have been ten miles apart. As it was, his telegraph looked like little more than a pointless parlor trick to busy men who believed they had more important things to worry about.

So, Morse decided to try his luck in Europe. Upon arriving there, he learned to his discomfiture that various Europeans were already working on the same project he was. In particular, a pair of Britons named William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone, building upon the ideas and experiments of a Russian nobleman named Pavel Lvovitch Schilling, had made considerable progress on a system which transmitted signals over a set of ten wires to a set of five needles, causing them to tilt in different directions and thereby to signify different letters of the alphabet.

Morse pointed out to anyone who would listen that this system’s need for so many wires made it far more complicated, expensive, and delicate than his own system, which required just one.Yet few of the Europeans Morse met showed much interest in yet another electric-telegraph project, much less one from the other side of the Atlantic. He grew almost frantic with worry that one of the European projects would pan out before he could get his own telegraph into service. Against all rhyme and reason, he began claiming that Cooke and Wheatstone had stolen from him the very idea for an electric telegraph; it had, he said, probably reached them through one of the other passengers who had sailed on the Sully back in 1832. This was of course absurd on the face of it; the idea of an electric telegraph in the broad strokes had been batted about for decades by that point. Morse’s invention was a practical innovation, not a conceptual one. Yet he heatedly insisted that he alone was the father of the electric telegraph in every sense. Europeans didn’t hesitate to express their own opinion to the contrary. The argument quickly got personal. One French author, for example, took exception with Morse’s habit of calling himself a “professor.” “It may be well to state here,” he sniffed, “that he [is] merely professor of literature and drawing, by an honorary title conferred upon him by the University of New York.”

Morse returned to the United States in early 1839 a very angry man. He now enlisted the nativist American press in his cause. “The electric telegraph, that wonder of our time, is an American discovery,” wrote one broadsheet. “Professor Morse invented it immediately after his return from France to America.” To back up his claim of being the victim of intellectual theft, Morse even tracked down the Sully‘s captain and got him to testify that Morse had indeed spoken of his stroke of genius freely to everyone onboard.

But even Morse had to recognize eventually that such pettiness availed him little. There came a point, not that long after his return to American shores, when he seemed ready to give up on his telegraph and all the bickering that had come to surround it in favor of a new passion. While visiting Paris, he had seen some of the first photographs taken by Louis Daguerre, had even visited the artist and inventor personally in his studio. He had brought one of Daguerre’s cameras back with him, and now, indefatigable as ever, he set up his own little studio; the erstwhile portrait painter became New York City’s first portrait photographer, as well as a teacher of the new art form. His knack for rubbing shoulders with Important Men of History hadn’t deserted him: among his students was one Mathew Brady, whose images of death and destruction from the battlefields of the American Civil War would later bring home the real horrors of war to civilians all over the world for the first time. Morse also plunged back into reactionary politics with a passion; he ran again, still unsuccessfully, for mayor of New York on an anti-immigration, anti-Catholic, pro-slavery platform.

So, Morse might have retired quietly from telegraphy, if not for an insult which he simply couldn’t endure. Over in Britain, Cooke and Wheatstone had been making somewhat more headway. They had found that the men behind the new railroads that were then being built showed some interest in their telegraph as a means of keeping tabs on the progress of trains and avoiding that ultimate disaster of a collision. In 1839, Cooke and Wheatstone installed the first electric telegraph ever to be put into everyday service, connecting the 13 miles (21 kilometers) that separated Paddington from West Drayton along Britain’s Great Western Railway. Several more were installed over the next few years on other densely trafficked stretches. One story has it that, when three of the five indicator needles on the complex system conked out on one of the lines, the operators in the stations improvised a code for passing all the information they needed to using only the remaining two needles. The lesson thus imparted would only slowly dawn on our would-be electric-telegraph entrepreneurs on both sides of the Atlantic: that both of their systems were actually more complicated than they needed to be, that a simpler system would be cheaper and more reliable while still doing everything it needed to.

But first, the insult: flush with their relative success, Cooke and Wheatstone wrote to Morse in early 1842 to ask whether, in light of all his experience with electric telegraphy in general, he might be interested in peddling their system to the railroads in his country — in becoming, in other words, a mere salesman for their telegraph. It may have been intended as an honest conciliatory overture, a straightforward attempt to bury the hatchet. But that wasn’t how Morse took it. Livid at this affront to his inventor’s pride, he jumped back into the telegraphy game with a vengeance; he soon extended his system’s maximum range to 33 miles (53 kilometers).

He wrote a deferential letter to Joseph Henry, whose experiments had by now won him a position on the faculty of Princeton University and the reputation of the leading authority in the country on long-distance applications of electricity. Morse knew that, if he could get Henry to throw his weight behind his telegraph, it might make all the difference. “Have you met with any facts in your experiments thus far that would lead you to think that my mode of telegraphic communication will prove impracticable?” he asked in his letter. Not only did Henry reply in the negative, but he invited Morse up to Princeton to talk in person. This was, needless to say, exactly what Morse had been hoping for. Henry agreed to support Morse’s telegraph, even to publicly declare it to be a better design than its competitor from Britain.

Thus Henry was in attendance when Morse exhibited his telegraph in New York City in the summer of 1842, garnering for it the first serious publicity it had received in a couple of years. Morse continued beavering away at it, adding an important new feature: a sending and receiving station at each end of the same wire, to turn his telegraph into an effortless two-way communications medium. The British system, by contrast, required no fewer than twenty separate wires to accomplish the same thing. In December of 1842, the growing buzz won Morse another hearing in Washington, D.C. Knowing that this was almost certainly his last chance to secure government funding, he lobbied for and got access to two separate audience halls. He installed one station in each, and he and Alfred Vail then mediated a real-time conversation between two separate groups of politicians and bureaucrats who could neither see nor hear one another.

This added bit of showmanship seemed to do the trick; at last some of those assembled seemed to grasp the potential of what they were seeing. A bill was introduced to allocate $30,000 to the construction of a trial line connecting Washington, D.C., to Baltimore, a distance of 40 miles (65 kilometers). On February 23, 1843, it passed the House by a vote of 89 to 83, with 70 abstainers. On March 3, the Senate passed it unanimously as a final piece of business in the literal last minute of the current term, and President John Tyler signed it. More than a decade after the idea had come to him aboard the Sully, Morse finally had his chance to prove to the world how useful his telegraph could be.

He had no small task before him: no one in the country had ever attempted to run a permanent electrical cable over a distance of 40 miles before. Morse asked the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company for permission to use their right-of-way between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. They agreed, in return for free use of the telegraph, thus further cementing a connection between railroads and telegraphs that would persist for many years.

The project was beset with difficulties from the start. A plan to lay the cable underground, encased within custom-manufactured lead pipe, went horribly awry when the latter proved to be defective. The team had to pull it all up again, whereupon Morse decided to string the cable along on poles instead, where it would be more exposed to the elements and to vandals but also much more accessible to repair crews; thus was born the ubiquitous telegraph — later telephone — pole.

This experience may have taught Morse something of the virtues of robust simplicity. At any rate, it was during the construction of the Washington-to-Baltimore line that he finally abandoned his complicated electrical printing press in favor of a sending apparatus that was about as simplistic as it could be. It was apparently Alfred Vail rather than Morse himself who was primarily responsible for designing what would be immortalized as the “Morse key”: a single switch which the operator could use to close and open the circuit breaker manually. The receiving station, on the other hand, remained largely unchanged: a pencil or pen made marks on a paper tape turning beneath it.

The Morse key. For well over a century the principal tool and symbol of the telegraph operator’s trade, it was actually a last-minute modification of a more ambitious design.

To facilitate communication using such a crude tool, Morse and Vail created the first draft of the system that would be known forevermore as Morse code. After being further refined and simplified by the German Friedrich Clemens Gerke in 1848, Morse code became the first widely used binary communications standard, the ancestor of later computer protocols like ASCII. In lieu of the zeroes and ones of the computer age, it encoded every letter and digit as a series of dots and dashes, which the operator at the sending end produced on the roll of paper at the other end of the line by pressing and releasing the Morse key quickly (in the case of a dot) or pressing and holding it for a somewhat longer time (in the case of a dash). The system demanded training and practice, not to mention significant manual dexterity, and was far from entirely foolproof even with a seasoned operator on each end of the line. Nonetheless, plenty of people would get very, very good at it, would learn practically to think in Morse code and to transcribe any text into dots and dashes almost as fast as you or I might type it on a computer keyboard. And they would learn to turn a received sequence back into characters on the page with equal facility. The electromagnet attached to the stylus on the receiving end gave out a distinct whine when it was engaged; thanks to this, operators would soon learn to translate messages by ear alone in real time. The sublime ballet of a telegraph line being operated well would become a pleasure to watch, in that way it is always wonderful to watch competent people who take pride in their skilled work going about it.

On May 24, 1844, the Washington-to-Baltimore telegraph line was officially opened for business. Before an audience of journalists, politicians, and other luminaries, Morse himself tapped out the first message in, of all places, the chambers of the Supreme Court of the United States. At the other end of the line in Baltimore, Alfred Vail decoded it before an audience of his own. “What hath God wrought?” it read, a phrase from the Old Testament’s Book of Numbers.

For our purposes, a perhaps more appropriate question might be, “What hath the telegraph wrought?” Thanks to Samuel Morse and his fellow travelers, the first stepping stone toward a World Wide Web had fallen into place.

(Sources: the books A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet by John Naughton; The Victorian Internet by Tom Standage; From Gutenberg to the Internet: A Sourcebook on the History of Information Technology edited by Jeremy M. Norman; The Greek Plays edited by Mary Lefkowitz and James Romm; Les Télégraphes by A.L. Ternant, Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison by Michael B. Schiffer, and Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F.B. Morse by Kenneth Silverman. And the paper “The Telegraph of Claude Chappe: An Optical Communications Network for the XVIIIth Century” by J.M. Dilhac.)