Why does the sinking of the Titanic have such a stranglehold on our imaginations? The death of more than 1500 people is tragic by any standard, but worse things have happened on the world’s waters, even if we set aside deliberate acts of war. In 1822, for example, the Chinese junk Tek Sing ran into a reef in the South China Sea, drowning all 1600 of the would-be immigrants to Indonesia who were packed cheek-by-jowl onto its sagging deck. In 1948, the Chinese passenger ship Kiangya struck a leftover World War II mine shortly after departing Shanghai, killing as many as 4000 supporters of Chiang Kai-shek’s government who were attempting to flee the approaching Communist armies. In 1987, the Philippine ferry Doña Paz collided with an oil tanker near Manila, killing some 4300 people who were just trying to get home for Christmas.

But, you may object, these were all East Asian disasters, involving people for whom we in the West tend to have less immediate empathy, for a variety of good, bad, and ugly reasons. It’s a fair point. And yet what of the American paddle-wheel steamer Sultana, whose boiler exploded as it plied the Mississippi River in 1865, killing about 1200 people, or only 300 fewer than died on the Titanic?

I’m comfortable assuming that, unless you happen to be a dedicated student of maritime lore or of Civil War-era Americana, you probably don’t know much about any of these disasters. But everyone — absolutely everyone — seems to know at least the basic outline of what happened to the Titanic. Why?

It seems to me that the sinking of the Titanic is one of those rare occasions when History stops being just a succession of one damn thing after another, to paraphrase Arnold Toynbee, and shows some real dramatic flair. The event has enough thematic heft to curl the toes of William Shakespeare: the pride that goeth before a fall (no one will ever dare to call a ship “unsinkable” again); the cruelty of fate (experts have estimated that, if the Titanic somehow could have been raised and put into service once again, it could have made a million more Atlantic crossings without bumping into any more icebergs); the artificiality of money and social status (a form of communism far purer than anything ever implemented in the Soviet Union or China reigned in the Titanic‘s lifeboats); the crucible of character in the breach (some people displayed tremendous, selfless bravery when faced with the ultimate existential impasse of their lives, while others behaved… less well). Unlike the aforementioned shipwrecks, all of which were short, sharp shocks, the sinking of the Titanic was a slow-motion tragedy that took place over the course of two and a half hours. This gave ample space for all of the aforementioned themes to play out. The end result was almost irresistibly dramatic, if you’ll excuse my callousness in writing about it like a film prospectus.

And then, of course, there is the power of the Titanic as a symbol of changing times, as an almost tangible way point in history. The spirit of a century doesn’t always line up neatly with the numbers in our calendars; the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were actually unusual in setting the tone for our muddled, complicated 21st-century existences so soon after we were all cheering our escape from the Y2K crisis and drinking toasts to The End of History on January 1, 2000. By way of contrast, one might say that the nineteenth century didn’t really get going in earnest until Napoleon was defeated once and for all at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Similarly, one could say that the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 makes for a much more satisfying fin de siècle than anything that occurred in 1900. On that cold April night in the North Atlantic, an entire worldview sank beneath the waves, a glittering vision of progress as an inevitability, of industry and finance and social refinement as a guarantee against any and all forms of unpleasantness, of war — at least war between the proverbial great powers — as a quaint relic of the past. Less than two and a half years after the Titanic went down, the world was plunged into the bloodiest war it had ever known.

That, anyway, is how we see the sinking of the Titanic today. Many people of our own era are surprised, even though they probably shouldn’t be, that the event’s near-mythic qualities went completely unrecognized at the time; the larger currents of history tend to make sense only in retrospect. While the event was certainly recognized as an appalling tragedy, it was not seen as anything more than that. Rather than trying to interrogate the consciousness of the age, the governments of both Britain and the United States took a more practical tack, endeavoring to get to the bottom of just what had gone wrong, who had been responsible, and how they could prevent anything like this from ever happening again. There followed interminable hearings in the Houses of Parliament and the Capitol Building, while journalists gathered the stories of the 700-odd survivors and wrote them up for a rapt public. But no one wrote or spoke of the event as any sea change in history, and in due course the world moved on. By the time the British luxury liner Lusitania, the queen of the Atlantic-crossing trade prior to the construction of the Titanic and its two sister ships, was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915 — loss of life: 1200 — the Titanic was fading fast from the public consciousness, just another of those damn things that had happened before the present ones.

“Had the Titanic been a mud scow with the same number of useful workingmen on board and had it gone down while engaged in some useful social work,” wrote a muckraking left-wing Kansan newspaper, “the whole country would not have gasped with horror, nor would all the capitalist papers have given pages for weeks to reciting the terrible details.” This was harsh, but undeniably true. The only comfort for our Kansan polemicists, if it was comfort, was that the Titanic looked likely to be forgotten just as completely as that hypothetical mud scow would have been in the fullness of time.

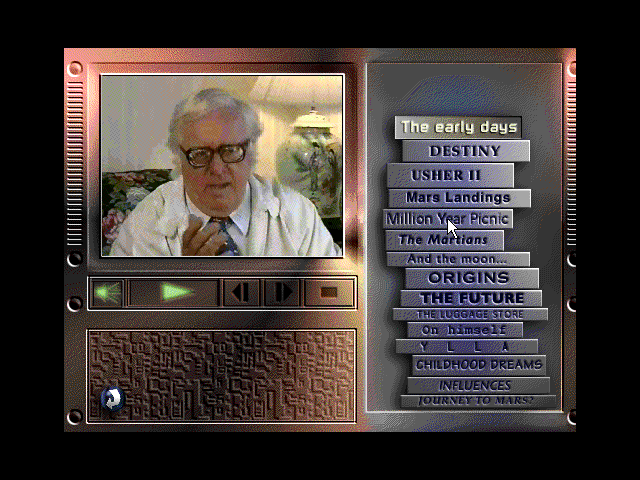

But then, in the 1950s, the Titanic was scooped out of the dustbin of history and turned into an icon for the ages by a 30-something American advertising executive and part-time author named Walter Lord, who had crossed the Atlantic as a boy aboard the Titanic‘s sister the Olympic and been fascinated by the ships’ stories ever since. Lord’s editor was unenthusiastic when he proposed writing the first-ever book-length chronicle of that fateful night, but grudgingly agreed to the project at last, as long as Lord wrote “in terms of the people involved instead of the ship.” Accordingly, Lord interviewed as many of the living survivors and their progeny as he could, then wove their stories together into A Night to Remember, a vividly novelistic minute-by-minute account of the night in question that has remained to this day the classic book about the Titanic, a timeless wellspring of lore and legend. It was Lord, for example, who first told the story of the ship’s band bravely playing on in the hope of comforting their fellow passengers, until the musicians and their music were swallowed by the ocean along with their audience. Ditto the story of the ship’s stoic Captain Edward Smith, who directed his crew to save as many passengers as they could and then to save themselves if possible, while he followed the unwritten law of the sea and went down with his ship. Published in November of 1955, A Night to Remember became an instant bestseller and a veritable cultural sensation. Walter Lord became Homer to the Titanic‘s Trojan War, pumping tragedy full of enough heroism, romance, and melodrama to almost — almost, mind you — make us wish we could have been there.

The book was soon turned into an American teleplay that was reportedly seen by an astonishing 28 million people. “Millions, perhaps, learned about the disaster for the first time,” mused Lord later about the evening it was broadcast. “More people probably thought about the Titanic that night than at any time since 1912.” (Sadly, every trace of this extraordinary cultural landmark has been lost to us because it was shot and broadcast live without ever touching film or videotape, as was the norm in those days). The book then became a lavish British feature film in 1958. Surprisingly, the movie was a failure in the United States. Walter Lord blamed this on poor Stateside distribution on the part of the British producers and a newspaper strike in New York. A more convincing set of causes might begin with its lack of big-name stars, continue with the decision to shoot it in stately black and white rather than garish Technicolor, and conclude with the way it echoed the book in weaving together a tapestry of experiences rather than giving the audience just one or two focal points whom they could get to know well and root for.

Nevertheless, by the end of the 1950s the Titanic had been firmly lodged in the public’s imagination as mythology and metaphor, and it would never show any sign of coming unstuck. The first Titanic fan club — for lack of a better term — was founded in Massachusetts in 1960, whence chapters quickly spread around the country and the world. Initially called the Titanic Enthusiasts Society, the name was changed to the Titanic Historical Society after it was pointed out that being an “enthusiast” of a disaster like this one was perhaps not quite appropriate. But whatever the name under which they traveled, these were obsessive fans in the classic sense, who could sit around for hours debating the minutiae of their favorite ship’s brief but glamorous life in the same way that others of their ilk were dissecting every detail of the starship Enterprise. (Doug Woolley, the first person to propose finding the wreck and raising it back to the surface, was every inch a product of this milieu.)

“The story of the Titanic is a curious one because it rolled on and on,” said Walter Lord decades after writing his seminal book, “becoming more newsworthy as time went by.” Needless to say, A Night to Remember has never come close to going out of print. Even as the 83 survivors who were still around in 1960 died off one by one and the mass-media spotlight shifted from them to the prospects of finding the wreck of the ship on which they had sailed all those years ago, it was always the stories of that one horrible night, with all of their pathos and their bizarre sort of glamour, that undergirded the interest. If there had been no Walter Lord to turn a disaster into a mythology, it would never have occurred to Jack Grimm and Robert Ballard to go in search of the real ship. It was thanks to 30 years of tellings and retellings of the Titanic story that those first pictures of the ship sent up from the depths by Ballard felt like coming face to face with Leviathan. For by the 1980s, you could use the Titanic as a simile, a metaphor, a parable, or just a trope in conversation with absolutely anyone, whether aged 9 or 90, and be certain that they would know what you were talking about. That kind of cultural ubiquity is extremely rare.

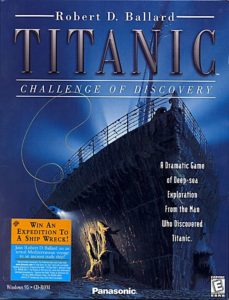

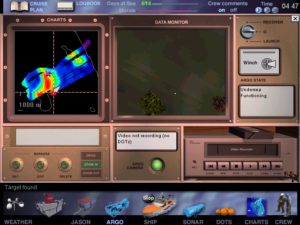

Thus we shouldn’t be stunned to learn that this totem of modern culture also inspired the people who made computer games. Even as some of their peers were casting their players as would-be Robert Ballards out to find and explore the wreck, others were taking them all the way back to the night of April 14, 1912, and asking them to make the best of a no-win situation.

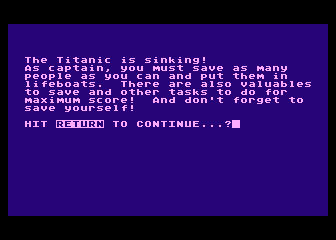

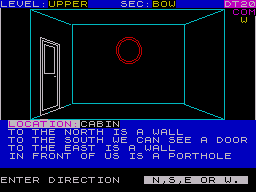

The very first Titanic computer game of any stripe that I know of was written by an American named Peter Kirsch, the mastermind of SoftSide magazine’s “Adventure of the Month” club, whose members were sent a new text adventure on tape or disk every single month. Dateline Titanic was the game for May of 1982. Casting you as the ship’s captain, it begins with one of the cruelest fake-outs in any game ever. It seems to let you spot and dodge the deadly iceberg and change the course of history — until the message, “Oh, my God! You hit another one!” pops up. Simple soul that I am, I find this kind of hilarious.

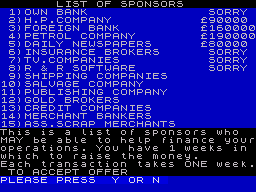

Anyway, we’re back in the same old boat, so to speak. The game does permit you to be a bit less of a romantic old sea dog than the real Captain Smith and to save yourself, although you’re expected to rescue as many passengers as you can first. In an article he wrote for SoftSide a few months after making the game, Kirsch noted that “the days of simply finding treasure and returning it to a storage location are gone forever.” But, stuck as he was with an adventure engine oriented toward exactly this “points for treasures” model, he faced a dilemma when it came time to make his Titanic game. He ended up with a design where, instead of scarfing up treasures and putting them in your display case for safe keeping, you have to grab as many passengers as possible and chunk them into lifeboats.

That said, it’s a not a bad little game at all, given the almost unimaginable technological constraints under which it was created. The engine is written in BASIC, and it combined with the actual game it enables have to be small enough to fit into as little as 16 K of memory. You can finish the game the first time whilst rescuing no one other than yourself, if necessary, then optimize your path on subsequent playthroughs until you’ve solved all of the puzzles in the right order, collected everyone, and gotten the maximum score; the whole experience is short enough to support this style of try-and-try-again gameplay without becoming too annoying. Whether it’s in good taste to treat a tragedy in this cavalier way is a more fraught question, but then again, it’s hard to imagine any other programmer doing much better under this set of constraints. It’s hard to pay proper tribute to the dead when you have to sweat every word of text you include as if you’re writing a haiku.

(Although Dateline Titanic was made in versions for the Radio Shack TRS-80, Apple II, and Atari 8-bit line, only the last appears to have survived. Feel free to download it from here. Note that you’ll need an Atari emulator such as the one called simply Atari800. And you’ll also need Atari’s BASIC cartridge. Unfortunately, the emulator is not a particularly user-friendly piece of software, with an interface that is entirely keyboard-driven. You access the menu by hitting the F1 key. From here, you want to first mount the BASIC cartridge: “Cartridge Management -> Cartridge.” Press the Escape key until you return to the emulator’s main screen. You should see a “READY” prompt. Now you can run the “.atr” file by pressing F1 again, then choosing “Run Atari Program.” Be patient; it will take the game a moment to start up fully.)

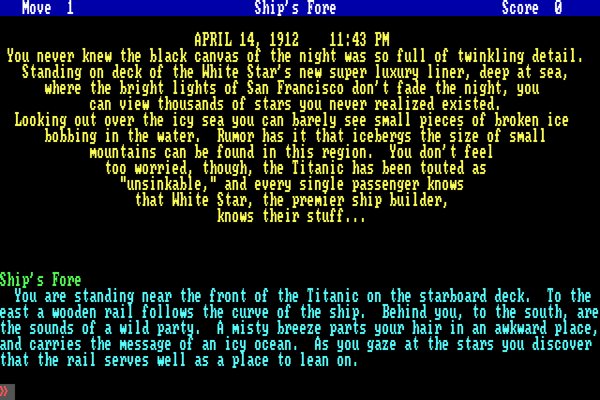

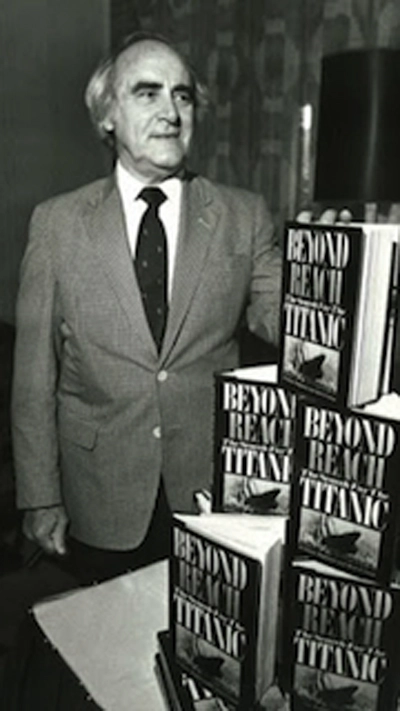

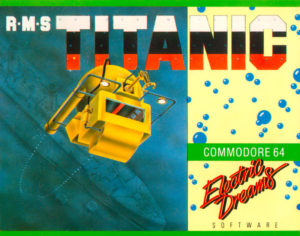

Four years later, in the midst of the full-blown Titanic mania ignited by Robert Ballard’s discovery of the wreck, another Titanic text adventure appeared, again as something other than a standard boxed game. Beyond the Titanic by Scott Miller is interesting today mostly as a case of humble beginnings. After releasing this game and a follow-up text adventure as shareware to little notice and less profit, Miller switched his focus to action games. He and his company Apogee Entertainment then became the primary impetus behind an underground movement which bypassed the traditional publishers and changed the character of gaming dramatically in the early 1990s by providing a more rough-and-ready alternative to said publishers’ obsession with high-concept “interactive movies.” For all that it belongs to a genre whose commercial potential was already on the wane by 1986, Beyond the Titanic does display the keen instinct for branding that would serve Miller so well in later years. The Titanic was a hot topic in 1986, and it was a name in the public domain, so why not make a game about it?

Beyond the Titanic itself is a strange beast, a game which is soundly designed and competently coded but still manages to leave a laughably bad final impression. Miller obviously didn’t bother to do much if any research for his game. Playing the role of a sort of anti-Captain Smith, you escape from the sinking ship all by yourself in one of its lifeboats and leave everyone else to their fate. Luckily for you, in Miller’s world a lifeboat is apparently about the size of a canoe and just as easy for one person to paddle. (In reality, the lifeboats were larger than many ocean-going pleasure boats, being 30 feet long and 9 feet wide.)

Your escape doesn’t mark the end of the game but its real beginning. Now aliens enter the picture, sucking you into a cave complex hidden below the ocean. From this point on, the game lives up to its title by having nothing else to do with the Titanic; the plot eventually sends you into outer space and finally on a trip through time. “Overstuffed” is as kind a descriptor as I can find for both the plot and the writing. This one is best approached in the spirit of an Ed Wood film; Miller tries valiantly to grab hold of the right verbs and adjectives, but they’re forever flitting out of his grasp like fireflies on a summer night. Suffice to say that Beyond the Titanic won’t leave anyone regretting that he abandoned text adventures for greener pastures so quickly.

(Beyond the Titanic has been available for free from Scott Miller’s company 3D Realms since 1998. In light of that, I’ve taken the liberty of hosting a version here that’s almost ready to run on modern computers; just add your platform’s version of DOSBox.)

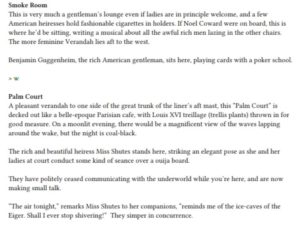

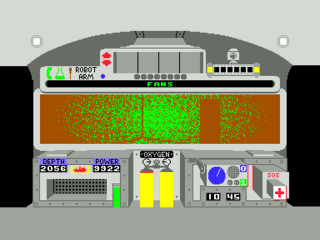

A relatively more grounded take on the Titanic‘s one and only voyage appeared in 1995 as one of the vignettes in Jigsaw, Graham Nelson’s epic time-travel text adventure, which does have the heft to support its breadth. Indeed, Nelson’s game was the first ever to deliver a reasonably well-researched facsimile of what it was actually like to be aboard the doomed ship before and after it struck the iceberg. A fine writer by any standard, he describes the scenes with the appropriate gravity as you wander a small subsection of the ship’s promenades, staterooms, lounges, and crew areas.

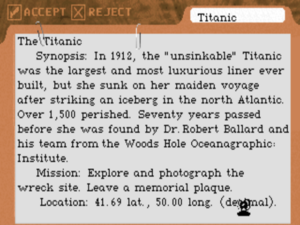

Making a satisfying game out of the sinking of the Titanic presents a challenge for a designer not least in that really is the very definition of a no-win scenario: to allow the player to somehow avert the disaster would undercut the whole reason we find the ship so fascinating, yet to make a game simply about escaping doesn’t feel all that appropriate either. Many designers, including Scott Miller and now Graham Nelson in a far more effective way, therefore use the sinking ship and all of the associated drama as a springboard for other, original plots. (Because you’re a time traveler in Jigsaw, escape isn’t even an issue for you; you can ride the time stream out of Dodge whenever you feel like it.) Nelson imagines that the fabulously wealthy Benjamin Guggenheim, one of the glitterati who went down with the ship, is also a spy carrying a vital dispatch meant for Washington, D.C. Because Guggenheim, honorable gentleman that he is, would never think of getting into a lifeboat as long as women and children are still aboard the ship, he entrusts you with getting the message into the hands of a co-conspirator whose gender gives her a better chance of surviving: the “rich and beautiful heiress Miss Shutes.”

It must be emphasized that the Titanic is only a vignette in Jigsaw, one of fifteen in the complete game. Thus it comes as no surprise that the espionage plot isn’t all that well developed, or even explained. In addition, there are also a few places where Nelson’s background research falls down. The Titanic was not the first vessel ever to send an “SOS” distress signal at sea, as he claims. And, while there was an Elizabeth Shutes aboard the ship, she was a 40-year-old governess employed by a wealthy family, not a twenty-something socialite. On the more amusing side, Jigsaw walkthrough author Bonni Mierzejewska has pointed out that the compass directions aboard the ship would seem to indicate that it’s sailing due east — a good idea perhaps in light of what awaits it on its westward progress, but a decidedly ahistorical one nonetheless.

Still, Jigsaw gets more right than wrong within the limited space it can afford to give the Titanic. I was therefore surprised to learn from Graham Nelson himself just a couple of years ago that “the Titanic sequence is the one I would now leave out.” While it’s certainly a famous event in history and an enduring sign of changing times, he argues, it wasn’t of itself a turning point in history like his other vignettes, at least absent the insertion of the fictional espionage plot: “Rich people drowned, but other rich people took their place, and history wasn’t much dented.” This is true enough, but I for one am glad the Titanic made the cut for one of my favorite text adventures of the 1990s.

(Jigsaw is available for free from the IF Archive. Note that you’ll need a Z-Machine interpreter such as Gargoyle to run it.)

Yet the most intriguing Titanic text adventure of all is undoubtedly the one that never got made. Steve Meretzky, one of Infocom’s star designers, was one of that odd species of Titanic “fan”; his colleagues remember a shelf filled with dozens of books on the subject, and a scale model of the ship he built himself that was “about as big as his office.” Shortly after his very first game for Infocom, the 1983 science-fiction comedy Planetfall, became a hit, Meretzky started pushing to make a Titanic game. Just like the previous two designers in this survey, he felt he had to add another, “winnable” plot line to accompany the ship’s dramatic sinking.

You are a passenger on the Titanic, traveling in Third Class to disguise the importance of your mission: transporting a MacGuffin from London to New York. As the [game] opens and you feel a long, drawn-out shudder pass through the ship, you must begin the process of escaping the restricted Third Class section, retrieving the MacGuffin from the purser’s safe amidst the confusion, and surviving the sinking to complete your delivery assignment. The actual events of those 160 minutes between iceberg and sinking would occur around you. I see this as a game of split-second timing that would require multiple [playthroughs] to optimize your turns in order to solve the puzzles in the shortest possible time. But you could also ignore all the puzzles and simply wander around the ship as a “tourist,” taking in the sights of this amazing event.

To his immense frustration, Meretzky never was able to drum up any enthusiasm for the idea at Infocom. In 1985, he was finally allowed to make a serious game as his reward for co-authoring the third best-selling text adventure in history, but even then his colleagues convinced him to opt for a science-fiction exercise called A Mind Forever Voyaging instead of the Titanic game. The latter remained something of a running joke at Meretzky’s expense for years. “It was almost a cliché,” says his colleague Dave Lebling. “Steve would say, ‘We should do a Titanic game!’ And we would all say, “No, no Titanic game. Go away, Steve.'”

The dream didn’t die for Meretzky even after Infocom closed up shop in 1989, and he moved on to design games for Legend Entertainment, a company co-founded by his fellow Infocom alum Bob Bates. Sadly, Bates too saw little commercial potential in a Titanic game, leaving Meretzky stuck in his comedy niche for all four of the games he made for Legend.

And still the fire burned. When Meretzky and Mike Dornbrook, another old Infocom colleague, decided to start their own studio called Boffo Games in 1994, the Titanic game was high on the agenda. The changing times meant that it had by now evolved from a text adventure into a point-and-click graphic adventure, with a fully fleshed-out plot that was to place aboard the ship the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, which really was stolen from the Louvre in 1911. (Ever since the painting was recovered from the thieves two years later, conspiracy theories claiming that the Mona Lisa which was hung once again in the Louvre is a face-saving forgery have abounded.) Meretzky and Dornbrook pitched their Titanic game to anyone and everyone who might be willing to fund it throughout Boffo’s short, frustrating existence, and even created a couple of rooms as a prototype. But they never could get anyone to bite. “We were saying, you know, there’s this new movie coming out,” says Dornbrook. “And it might do well. It will come out about the time the game will. It’s [James] Cameron. He sometimes does good stuff…” But it was to no avail. Meretzky made his very last adventure game to date in 1997, and it had nothing to do with the Titanic.

Instead it was left to another graphic adventure to ride the wave kicked up by the movie Dornbrook mentioned to sales that bettered the combined totals of all of the other Titanic games I’ve mentioned in these last two articles by an order of magnitude. I’ll examine that game in detail in the third and final article in this series. But first, allow me to set the table for its success via the origin story of the highest-grossing movie of the twentieth century.

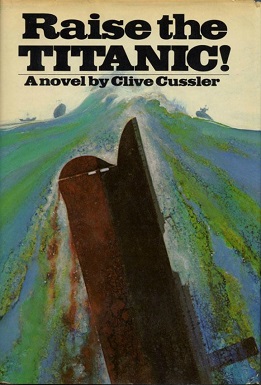

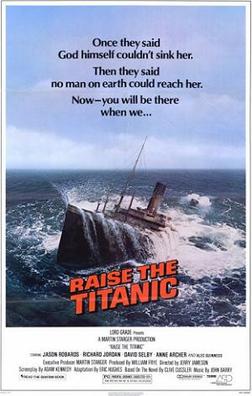

After the failures of the film versions of A Night to Remember and Raise the Titanic, the Hollywood consensus had become that nothing sank a feature film’s prospects faster than the Titanic. This was weird, given that the book A Night to Remember had spawned a cottage industry in print publishing and a whole fannish subculture to go along with it, but box-office receipts didn’t lie. The movers and shakers of Hollywood could only conclude that the public wanted a happy ending when they handed over their hard-earned money on a Friday night, which spelled doom for any film about one of the most infamously unhappy endings of all time. Even the full-fledged Titanic mania that followed Robert Ballard’s discovery of the wreck failed to sway the conventional wisdom.

But one prominent Hollywood director begged to differ. James Cameron was coming off the twin triumphs of The Terminator and Aliens in 1987, when he saw a National Geographic documentary that prominently featured Ballard’s eye-popping underwater footage of the wreck. An avid scuba diver, Cameron was entranced. He began to imagine a film that could unite the two halves of the Titanic‘s media legacy: the real sunken ship that lay beneath the waves and the glamorously cursed vessel of modern mythology. He jotted his thoughts down in his journal:

Do story with bookends of present-day scene of wreck using submersibles inter-cut with memory of a survivor and re-created scenes of the night of the sinking. A crucible of human values under stress. A certainty of slowly impending doom (metaphor). Division of men doomed and women and children saved by custom of the times. Many dramatic moments of separation, heroism, and cowardice, civility versus animal aggression. Needs a mystery or driving plot element woven through with all this as background.

The last sentence would prove key. Just like Scott Miller, Graham Nelson, and Steve Meretzky in the context of games, Cameron realized that his film couldn’t succeed as a tapestry of tragedy only. If it was to capture a wide audience’s interest, it needed the foreground plot and obvious set of protagonists that the film of A Night to Remember had so sorely lacked.

Yet Cameron’s own Titanic film would be a long time in coming. The melancholy splendor of that National Geographic documentary first did much to inform The Abyss, his moody 1989 movie about an American nuclear submarine’s close encounter with aliens. There then followed two more straightforward action vehicles starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Terminator 2 and True Lies.

Always, though, his Titanic movie stayed in the back of his mind. By 1995, he had more than a decade’s worth of zeitgeist-defining action flicks behind him, enough to make him the most bankable Hollywood crowd-pleaser this side of Steven Spielberg, with combined box-office receipts to his credit totaling more than $1.7 billion. With his reputation thus preceding him, he finally managed to convince an unusual pairing of 20th Century Fox and Paramount Pictures to share the risk of funding his dream project. Hollywood’s reluctance was by no means incomprehensible. In addition to the Titanic box-office curse, there was the fact that Cameron had never made a film quite like this one before. In fact, no one was making films like this in the 1990s; Cameron was envisioning an old-fashioned historical epic, a throwback to the likes of War and Peace, Cleopatra, and Gone with the Wind, complete with those films’ three-hour-plus running times.

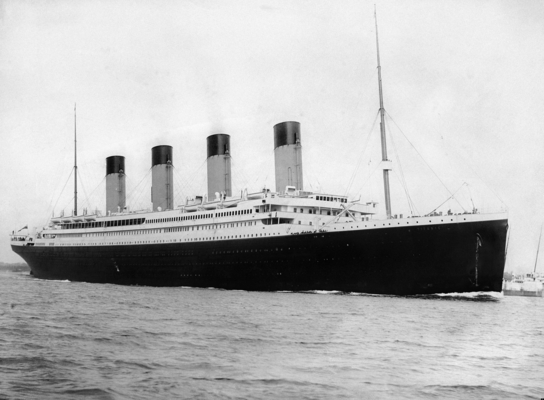

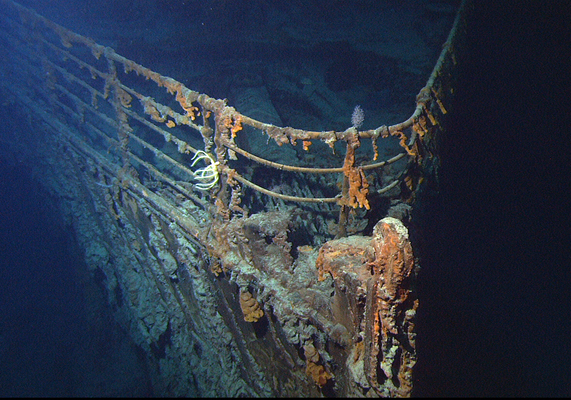

Cameron’s plan for his movie had changed remarkably little from that 1987 journal outline. He still wanted to bookend the main story with shots of the real wreck. He filmed this footage first, borrowing a Russian research vessel and deep-ocean submersible in September of 1995 in order to do so. Then it was time for the really challenging part. The production blasted out a 17-million-gallon pool on Mexico’s Baja coast and replicated the Titanic inside it at almost a one-to-one scale, working from the original builder’s blueprints. The sight of those iconic four smokestacks — the Titanic is the one ship in the world that absolutely everyone can recognize — looming up out of the desert was surreal to say the least, but it was only the beginning of the realization of Cameron’s vision. Everything that came within the view of a camera was fussed over for historical accuracy, right down to the pattern of the wainscotting on the walls.

Still hewing to the old-school formula for Hollywood epics, Cameron decided to make his foreground protagonists a pair of starstruck lovers from different sides of the economic divide: a prototypical starving artist from Steerage Class and a pampered young woman from First Class. This suited his backers very well; the stereotype-rooted but nevertheless timeless logic of their industry told them that men would come for the spectacle of seeing the ship go down, while women would come for the romance. The lead roles went to Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet, a pair of uncannily beautiful young up-and-comers. Pop diva Celine Dion was recruited to sing a big, impassioned theme song. For, if it was to have any hope of earning back its budget, this film would need to have something for everyone: action, romance, drama, a dash of comedy, and more than a little bit of sex appeal. (DiCaprio’s character painting Winslet’s in the altogether remains one of the more famous female nude scenes in film history.) But whether that would make it an entertainment spectacle for the ages or just an unwieldy monstrosity was up for debate.

The press at least knew where they were putting their money. When the project passed the $170 million mark to officially become the most expensive movie ever made, they had a field day. The previous holder of the record had been a deliriously misconceived 1995 fiasco called Waterworld, and the two films’ shared nautical theme was lost on no one. Magazines and newspapers ran headlines like “A Sinking Sensation” and “Glub! Glub! Glub!” before settling on calling Titanic — Cameron had decided that that simple, unadorned name was the only one that would suit his film — “the Waterworld of 1997.” By the time it reached theaters on December 19, 1997, six months behind schedule, its final cost had grown to $200 million.

And then? Well, then the press and public changed their tune, much to the benefit of the latest Titanic game.

(Sources: the books Sinkable: Obsession, the Deep Sea, and the Shipwreck of the Titanic by Daniel Stone, Titanic and the Making of James Cameron by Paula Parisi, A Night to Remember by Walter Lord, and The Way It Was: Walter Lord on His Life and Books edited by Jenny Lawrence; SoftSide of August 1982; the Voyager CD-ROM A Night to Remember. The information on Steve Meretzky’s would-be Titanic game is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me many years ago now, and from Jason’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents. Another online source was “7 of the World’s Deadliest Shipwrecks” at Britannica. My thanks to reader Peter Olausson for digging up a vintage newspaper headline that labels the Titanic “unsinkable” and letting me link to it.)