We approached games as immersive simulations. We wanted to build game environments that reacted to player’s decisions, that behaved in natural ways, and where players had more verbs than simply “shoot.” DOOM was not an influence on System Shock. We were trying something more difficult and nuanced, [although] we still had a lot of respect for the simplicity and focus of [the id] games. There was, to my recollection, a vague sense of fatalism about the parallel tracks the two companies were taking, since it was clear early on that id’s approach, which needed much less player education and which ran on adrenaline rather than planning and immersion, was more likely to be commercially successful. But we all believed very strongly in Looking Glass’s direction, and were proud that we were taking games to a more cerebral and story-rich place.

— Dorian Hart

We hope that our toiling now to make things work when it is still very hard to do effectively will mean that when it is easier to do, we can concentrate on the parts of the game that are less ephemeral than polygons per second, and distinguish ourselves by designing detailed and immersive environments which are about more than just the technology.

— Doug Church

In late 1992, two separate studios began working on two separate games whose descriptions sound weirdly identical to one another. Each was to make you the last human survivor on a besieged space station. You would roam its corridors in real time in an embodied first-person view; both studios prided themselves on their cutting-edge 3D graphics technology. As you explored, you would have to kill or be killed by the monsters swarming the complex. Yet wresting back control of the station would demand more than raw firepower: in the end, you would have to outwit the malevolent intelligence behind it all. Both games were envisioned as unprecedentedly rich interactive experiences, as a visceral new way of living through an interactive story.

But in the months that followed, these two projects that had started out so conceptually similar diverged dramatically. The team that was working on DOOM at id Software down in Dallas, Texas, decided that all of the elaborate plotting and puzzles were just getting in the way of the simpler, purer joys of blowing away demons with a shotgun. Lead programmer John Carmack summed up id’s attitude: “Story in a game is like story in a porn movie. It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” id discovered that they weren’t really interested in making an immersive virtual world; they were interested in making an exciting game, one whose “gameyness” they felt no shame in foregrounding.

Meanwhile the folks at the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based studio Looking Glass Technologies stuck obstinately to their original vision. They made exactly the uncompromising experience they had first discussed, refusing to trade psychological horror in for cheaper thrills. System Shock would demand far more of its players than DOOM, but would prove in its way an even more rewarding game for those willing to follow it down the moody, disturbing path it unfolded.

It was in this moment, then, that the differences between id and Looking Glass, the yin and the yang of 1990s 3D-graphics pioneers, became abundantly clear.

Looking Glass arrived at their crossroads moment just as they were completing their second game, Ultima Underworld II. Both it and its predecessor were first-person fantasy dungeon crawls set in and around Britannia, the venerable world of the Ultima CRPG series to which their games served as spinoffs. And both were very successful, so much so that they almost overshadowed Ultima VII, the latest entry in the mainline series. Looking Glass’s publisher Origin Systems would have been happy to let them continue making games in this vein for as long as their customers kept buying them.

But Looking Glass, evincing the creative restlessness that would define them throughout their existence, was ready to move on to other challenges. In the months immediately after Ultima Underworld II was completed, the studio’s head Paul Neurath allowed his charges to start three wildly diverse projects on the back of the proceeds from the Underworld games, projects which were unified only by their heavy reliance on 3D graphics. One was a game of squad-level tactical combat called Terra Nova, another a civilian flight simulator called Flight Unlimited. And the third — actually, the first of the trio to be officially initiated — was System Shock.

Doug Church, the driving creative force behind Ultima Underworld, longed to create seamless interactive experiences, where you didn’t so much play a game as enter into its world. The Underworld games had been a big step in that direction within the constraints of the CRPG form, thanks to their first-person, free-scrolling perspective, their real-time gameplay, and, not least, the way they cast you in the role of a single embodied dungeon delver rather than that of the disembodied manager of a whole party of them. But Church believed that there was still too much that pulled you out of their worlds. Although the games were played entirely from a single screen, which itself put them far ahead of most CRPGs in terms of immediacy, you were still switching constantly from mode to mode within that screen. “I felt that Underworld was sort of [four] different games that you played in parallel,” says Church. “There was the stats-based game with the experience points, the inventory-collecting-and-managing game, the 3D-moving-around game, and there was the talking game — the conversation-branch game.” What had seemed so fresh and innovative a couple of years earlier now struck Church as clunky.

Ironically, much of what he was objecting to is inherent to the CRPG form itself. Aficionados of the genre find it endlessly enjoyable to pore over their characters’ statistics at level-up time, to min-max their equipment and skills. And this is fine: the genre is as legitimate as any other. Yet Church himself found its cool intellectual appeal, derived from its antecedents on the tabletop which had no choice but to reveal all of their numbers to their players, to be antithetical to the sort of game that he wanted to make next:

In Underworld, there was all this dice rolling going on off-screen basically, and I’ve always felt it was kind of silly. Dice were invented as a way to simulate swinging your sword to see if you hit or miss. So everyone builds computer games where you move around in 3D and swing your sword and hit or miss, and then if you hit you roll some dice to simulate swinging a sword to decide if you hit or miss. How is anyone supposed to understand unless you print the numbers? Which is why, I think, most of the games that really try to be hardcore RPGs actually print out, “You rolled a 17!” In [the tabletop game of] Warhammer when you get a five-percent increase and the next time you roll your attack you make it by three percent, you’re all excited because you know that five-percent increase is why you hit. In a computer game you have absolutely no idea. And so we really wanted to get rid of all that super opaque, “I have no idea what’s going on” stuff. We wanted to make it so you can watch and play and it’s all happening.

So, there would be no numbers in his next game — no character levels, no character statistics, not even quantifiable hit points. There would just be you, right there in the world, without any intervening layers of abstraction.

Over the course of extensive discussions involving Doug Church himself, Paul Neurath, Looking Glass designer and writer Austin Grossman, and their Origin Systems producer Warren Spector, it was decided to make a first-person science-fiction game with distinct cyberpunk overtones, pitting you against an insane computer known as SHODAN. Cyberpunk was anything but a novelty in the games of the 1990s, a time when authors like William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Neal Stephenson all occupied prominent places on the genre-fiction bestseller charts and the game developers who read their novels rushed to bring their visions to life on monitor screens. Still, cyberpunk would suit Looking Glass’s purposes unusually perfectly by presenting a credible explanation for the diegetic interface Church was envisioning. You would play a character with a neural implant that let you “see” a heads-up display sporting a life bar for yourself, an energy bar for your weapons and other hardware, etc. — all of it a part of the virtual world rather than external to it. When you switched between “modes,” such as when bringing up the auto-map or your inventory display, it would be the embodied you who did so in the virtual world, not that other you who sat in front of the computer telling a puppet what to do next.

System Shock‘s commitment to its diegetic presentation is complete. As you discover new software and gadgets, they’re added to the heads-up display provided by your in-world neural implant. This serves the same purpose that leveling up did in Ultima Underworld, but in a more natural, realistic way.

Dissatisfied with what he saw as the immersion-killing conversation trees of Ultima Underworld, Church decided to get rid of two-way conversation altogether. When the game began, there would be enticing signs that other humans were still alive somewhere on the space station, but you would be consistently too late to reach them; you would encounter them only as the zombies SHODAN turned them into after death. Of course, all of this too was highly derivative, and on multiple levels at that. Science-fiction fans had been watching their heroes take down out-of-control computers since the original Star Trek television series if not before; “I don’t think if you wrote the novel [of System Shock] it would fly off the shelves,” admits Church. Likewise, computer games had been contriving ways to place you in deserted worlds, or in worlds inhabited only by simple-minded creatures out for your blood, for as long as said games had existed, always in order to avoid the complications of character interaction; the stately isolation of the mega-hit adventure game Myst was only the most recent notable example of the longstanding tradition at the time System Shock was in development.

But often it’s not what you do in any form of media, it’s how well you do it. And System Shock does what it sets out to do very, very well indeed. It tells a story of considerable complexity and nuance through the artifacts you find lying about as you explore the station and the emails you receive from time to time, allowing you to piece it all together for yourself in nonlinear fashion. “We wanted to make the plot and story development of System Shock be an exploration as well,” says Church, “and that’s why it’s all in the logs and data, so then it’s very tied into movement through the spaces.”

Reading a log entry. The story is conveyed entirely through epistolary means like these, along with occasional direct addresses from SHODAN herself that come booming through the station’s public-address system.

Moving through said spaces, picking up bits and pieces of the horrible events which have unfolded there, quickly becomes highly unnerving. The sense of embodied realism that clings to every aspect of the game is key to the sense of genuine, oppressive fear it creates in its player. Tellingly, Looking Glass liked to call System Shock a “simulation,” even though it simulates nothing that has ever existed in the real world. The word is rather shorthand for its absolute commitment to the truth — fictional truth, yes, but truth nevertheless — of the world it drops you into.

Story is very important to System Shock — and yet, in marked contrast to works in the more traditionally narrative-oriented genre of the adventure game, its engine also offers heaps and heaps of emergent possibility as you move through the station discovering what has gone wrong here and, finally, how you might be able to fix it. “It wasn’t just, ‘Go do this sequence of four things,'” says Church. “It was, ‘Well, there are going to be twelve cameras here and you gotta take out eight of them. Figure it out.’ We [also] gave you the option [of saying], ‘I don’t want to fight that guy. Okay, maybe I can find another way…'”

Thus System Shock manages the neat trick of combining a compelling narrative with a completely coherent environment that never reduces you to choosing from a menu of options, one where just about any solution for any given problem that seems like it ought to work really does work. Just how did Looking Glass achieve this when so many others before and since have failed, or been so daunted by the challenges involved that they never even bothered to try? They did so by combining technical excellence with an aesthetic sophistication to which few of their peers could even imagine aspiring.

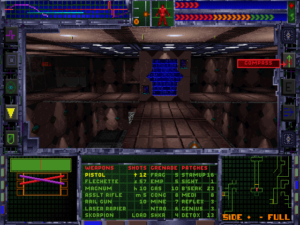

Just as the 3D engine that powers Ultima Underworld is more advanced than the pseudo-3D of id’s contemporaneous Wolfenstein 3D, the System Shock engine outdoes DOOM in a number of important respects. The enormous environments of System Shock curve over and under and around one another, complete with sloping floors everywhere; lighting is realistically simulated; you can jump and crouch and look up and down and lean around corners; you can take advantage of its surprisingly advanced level of physics simulation in countless ingenious ways. System Shock even boasts perspective-correct texture mapping, a huge advance over Ultima Underworld, and no easy thing to combine with the aforementioned slopes.

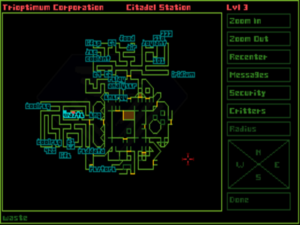

Each of the ten “levels” of System Shock is really multiple levels in the physical sense, as the corridors often curve over and under one another. Just as in Ultima Underworld, you can annotate the auto-map for yourself. But even with this aid, just finding your way around in these huge, confusing spaces can be a challenge in itself.

That said, it’s also abundantly true that a more advanced engine doesn’t automatically make for a better game. Any such comparison must always carry an implied addendum: better for whom? Certainly DOOM succeeded beautifully in realizing its makers’ ambitions, even as its more streamlined engine could run well on many more of the typical computers of the mid-1990s than System Shock‘s could. By no means do the engines’ respective advantages all run one way: in addition to being much faster than the System Shock engine, the DOOM engine allows rooms of arbitrary sizes and non-orthogonal walls, neither of which is true of its counterpart from Looking Glass.

In the end, System Shock wants to be a very different experience than DOOM, catering to a different style of play, and its own engine is designed to allow it to realize its own ambitions. It demands a more careful approach from its player, where you must constantly use light and shadow, walls and obstacles, to aid you in your desperate struggle. For you are not a superhuman outer-space marine in System Shock; you’re just, well, you, scared and alone in a space station filled with rampaging monsters.

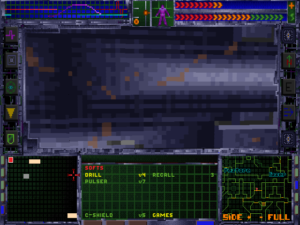

A fine example of the lengths to which Looking Glass’s technologists were willing to go in the service of immersion is provided by the mini-games you can play. Inspired by, of all things, the similarly plot-irrelevant mini-games found in the LucasArts graphic adventure Sam and Max Hit the Road, they contribute much more to the fiction in this case than in that other one. As with everything in System Shock, the mini-games are not external to the world of the main game. It’s rather you playing them through your neural implant right there in the world; it’s you who cowers in a safe corner somewhere, trying to soothe your soul with a quick session of Breakout or Missile Command. You get the chance to collect more and better games as you infiltrate the station’s computer network using the cyberspace jacks you find scattered about — a reward of sorts for a forlorn hacker trying to survive against an all-powerful entity and her horrifying minions.

Sean Barret, a programmer who came to Looking Glass and to the System Shock project well into the game’s development, implemented the most elaborate by far of the mini-games, a gentle satire of Origin Systems’s Wing Commander that goes under the name of Wing 0. The story of its creation is a classic tale of Looking Glass, a demonstration both of the employees’ technical brilliance and their insane levels of commitment to the premises of their games. Newly arrived on the team and wishing to make a good impression, Barrett saw a list of mini-game ideas on a whiteboard; a “Wing Commander clone” was among them. So, he set to work, and some days later presented his creation to his colleagues. They were as shocked as they were delighted; it turned out that the Wing Commander clone had been a joke rather than a serious proposal. In the end, however, System Shock got its very own Wing Commander after all.

Still, there were many other technically excellent and crazily dedicated games studios in the 1990s, just as there are today. What truly set Looking Glass apart was their interest in combining the one sort of intelligence with another kind that has not always been in quite so great a supply in the games industry.

As Looking Glass grew, Paul Neurath brought some very atypical characters into the fold. Already in late 1991, he placed an advertisement in the Boston Globe for a writer with an English degree. He eventually hired Austin Grossman, who would do a masterful job of scattering the puzzle pieces of Doug Church’s story outline around the System Shock space station. There soon followed another writer with an English degree, this one by the name of Dorian Hart, who would construct some of the station’s more devious internal spaces using the flair for drama which he had picked up from all of the books he had read. He was, as he puts it, “a liberal-arts nobody with no coding skills or direct industry experience, thrown onto arguably the most accomplished and leading-edge videogame production team ever assembled. It’s hard to explain how unlikely that was, and how fish-out-of-water I felt.” Nevertheless, there he was — and System Shock was all the better for his presence.

Another, even more unlikely set of game developers arrived in the persons of Greg LoPiccolo and Eric and Terri Brosius, all members of a popular Boston rock band known as Tribe, who had been signed to a major label amidst the Nirvana-fueled indie-rock boom of the early 1990s, only to see the two albums they recorded fail to duplicate their local success on a national scale. They were facing a decidedly uncertain future when Doug Church and Dan Schmidt — the latter being another Looking Glass programmer, designer, and writer — showed up in the audience at a Tribe show. They loved the band’s angular, foreboding songs and arrangements, they explained afterward, and wanted to know if they’d be interested in doing the music for a science-fiction computer game that would have much the same atmosphere. Three members of the band quickly agreed, despite knowing next to nothing about computers or the games they played. “Being young, not knowing what would happen next, that was part of the magic,” remembers Eric Brosius. “We were willing to learn because it was just an exciting time.”

Terri Brosius became the voice of SHODAN, a role that fell to her by default: artificial intelligences in science fiction typically spoke in a female voice, and she was the only woman to be found among the Looking Glass creative staff. But however she got the part, she most definitely made it her own. She laughs that “people tend to get freaked out” when they hear her speak today in real life. And small wonder: her glitchy voice ringing through the empty corridors of the station, dripping with sarcastic malice, is one of the indelible memories that every player of System Shock takes away with her. Simply put, SHODAN creeps you the hell out. “You had a recurring, consistent, palpable enemy who mattered to you,” notes Doug Church — all thanks to Austin Grossman’s SHODAN script and Terri Brosius’s unforgettable portrayal of her.

As I think about the combination of technical excellence and aesthetic sophistication that was Looking Glass, I find one metaphor all but unavoidable: that of Looking Glass as the Infocom of the 1990s. Certainly Infocom, their predecessors of the previous decade on the Boston-area game-development scene, evinced much the same combination — the same thoroughgoing commitment to excellence and innovation in all of their forms — during their own heyday. If the 3D-graphics engines of Looking Glass seem a long way from the text and parsers of Infocom, let that merely be a sign of just how much gaming itself had changed in a short span of time. Even when we turn to more plebeian matters, there are connections to be found beyond a shared zip code. Both studios were intimately bound up with MIT, sharing in the ideas, personnel, and, perhaps most of all, the culture of the university; both had their offices on the same block of CambridgePark Drive; two of Looking Glass’s programmers, Dan Schmidt and Sean Barrett, later wrote well-received textual interactive fictions of their own. The metaphor isn’t ironclad by any means; Legend Entertainment, founded as it was by former Infocom author Bob Bates and employing the talents of Steve Meretzky, is another, more traditionalist answer to the question of the Infocom of the 1990s. Still, the metaphor does do much to highlight the nature of Looking Glass’s achievements, and their importance to the emerging art form of interactive narrative. Few if any studios were as determined to advance that art form as these two were.

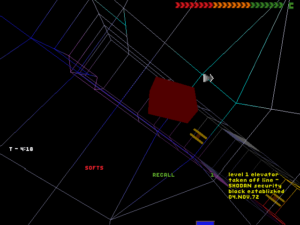

But Looking Glass’s ambitions could occasionally outrun even their impressive abilities to implement them, just as could Infocom’s at times. In System Shock, this overreach comes in the form of the sequences that begin when you utilize one of those aforementioned cyberspace jacks that you find scattered about the station. System Shock‘s cyberspace is an unattractive, unwelcoming place — and not in a good way. It’s plagued by clunky controls and graphics that manage to be both too minimalist and too garish, that are in fact almost impossible to make head or tail of. The whole thing is more frustrating than fun, not a patch on the cyberspace sequences to be found in Interplay’s much earlier computer-game adaption of William Gibson’s breakthrough novel Neuromancer. So, it turns out that even the collection of brilliant talent that was assembled at Looking Glass could have one idea too many. Doug Church:

We thought [that] it fit from a conceptual standpoint. You’re a hacker; shouldn’t you hack something? We thought it would be fun to throw in a different movement mode that was more free-form, more action. In retrospect, we probably should have either cut it or spent more time on it. There is some fun stuff in it, but it’s not as polished as it should be. But even so, it was nice because it at least reinforced the idea that you were the hacker, in a totally random, arcadey, broken kind of way. But at least it suggested that you’re something other than a guy with a gun. We were looking at ourselves and saying, “Oh, of course we should have cyberspace! We’re a cyberpunk game, we gotta have cyberspace! Well, what can we do without too much time? What if we do this crazy thing?” Off we went…

By way of compounding the problem, the final confrontation with SHODAN takes place… in cyberspace. This tortuously difficult and thoroughly unfun finale has proven to be too much for many a player, leaving her to walk away on the verge of victory with a terrible last taste of the game lingering in her mouth.

Luckily, it’s possible to work around even this weakness to a large extent, thanks to another of the generous affordances which Looking Glass built into the game. You can decide for yourself how complex and thus how difficult you wish the game to be along four different axes: Combat (the part of the game that is most like DOOM); Mission (the non-combat tasks you have to accomplish to free the station from SHODAN’s grip); Puzzle (the occasional spatial puzzles that crop up when you try to jigger a lock or the like); and Cyber (the cyberspace implementation). All of these can be set to a value between zero and three, allowing you to play System Shock as anything from a straight-up shooter where all you have to do is run and gun to an unusually immersive and emergent pure adventure game populated only by “feeble” enemies who “never attack first.” The default experience sees all of these values set at two, and this is indeed the optimal choice in my opinion for those who don’t have a complete aversion to any one of the game’s aspects — with one exception: I would recommend setting Cyber to one or even zero in order to save yourself at lot of pain, especially at the very end. (The ultimate challenge for System Shock veterans, on the other hand, comes by setting the Mission value to three; this imposes a time limit on the whole game of about seven hours.)

System Shock was released in late 1994, almost two full years after Ultima Underworld II, Looking Glass’s last game. It sold acceptably but not spectacularly well for a studio that was already becoming well-acquainted with the financial worries that would continue to dog them for the rest of their existence. Reviews were quite positive, yet many of the authors of same seemed barely to have noticed the game’s subtler qualities, choosing to lump it in instead with the so-called “DOOM clones” that were beginning to flood the market by this point, almost a year after the original DOOM‘s release. (One advantage of id Software’s more limited ambitions for their game was the fact that it was finished much, much quicker than System Shock; in fact, a DOOM II was already on store shelves by the time System Shock made it there.)

Although everyone at Looking Glass took the high road when asked about the DOOM connection, the press and public’s tendency to diminish their own accomplishment in 3D virtual-world-building had to rankle at some level; former employees insist to this day that DOOM had no influence whatsoever on their own creation, that System Shock would have turned out the same even had DOOM never existed. The fact is, Looking Glass’s own claim to the title of 3D-graphics pioneers is every bit as valid as that of id, and their System Shock engine actually was, as we’ve seen, more advanced than that of DOOM in a number of ways. No games studio in history has ever deserved less to be treated as imitators rather than innovators.

Alas, mainstream appreciation would be tough to come by throughout the remaining years of Looking Glass’s existence, just as it had sometimes been for Infocom before them. A market that favored the direct, visceral pleasures of id’s DOOM and, soon, Quake didn’t seem to know quite what to do with Looking Glass’s more nuanced 3D worlds. And so, yet again as with Infocom, it would not be until after Looking Glass was no more that the world of gaming would come to fully appreciate everything they had achieved. When asked pointedly about the sales charts which his games so consistently failed to top, Doug Church showed wisdom beyond his years in insisting that the important thing was just to earn enough back to make the next game.

id did a great job with [DOOM]. And more power to them. I think you want to do things that connect with the market and you want to do things that people like and you want to do things that get seen. But you also want to do things you actually believe in and you personally want to do. Hey, if you’re going to work twenty hours a day and not get paid much money, you might as well do something you like. We were building the games we were interested in; we had that luxury. We didn’t have spectacular success and a huge win, but we had enough success that we got to do some more. And at some level, at least for me, sure, I’d love to have huge, huge success. But if I get to do another game, that’s pretty hard to complain about.

Today, free of the vicissitudes of an inhospitable marketplace, System Shock more than speaks for itself. Few games, past or present, combine so many diverse ideas into such a worthy whole, and few demonstrate such uncompromising commitment to their premise and their fiction. In a catalog filled with remarkable achievements, System Shock still stands out as one of Looking Glass’s most remarkable games of all, an example of what magical things can happen when technical wizardry is placed in the service of real aesthetic sophistication. By all means, go play it now if you haven’t already. Or, perhaps better said, go live it now.

(Sources: the books Game Design Theory and Practice, second edition, by Richard Rouse III and System Shock: Strategies and Secrets by Bernie Yee; Origin’s official System Shock hint book; Origin’s internal newsletter Point of Origin from June 3 1994, November 23 1994, January 13 1995, February 10 1995, March 14 1995, and May 5 1995; Electronic Entertainment of December 1994; Computer Gaming World of December 1994; Next Generation of February 1995; Game Developer of April/May 1995. Online sources include “Ahead of Its Time: The History of Looking Glass” and “From Looking Glass to Harmonix: The Tribe,” both by Mike Mahardy of Polygon. Most of all, huge thanks to Dorian Hart, Sean Barrett, and Dan Schmidt for talking with me about their time at Looking Glass.

System Shock is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)

Steve McCrea

March 19, 2021 at 7:30 pm

I loved this game when it came out on floppy disk, even the cyberspace parts!

There are countless insights to be found in these fascinating interviews too:

http://gambit.mit.edu/updates/audio/looking_glass_studios_podcast/

(For example, just how much work it was to make Shodan sound like Shodan)

Joshua Barrett

March 19, 2021 at 8:08 pm

I love System Shock. But man, it can be hard to go back and replay, even by the standards of the era. The interface is clumsier than it really needs to be, although numerous people have patched in mouselook support in various ways over the years. This is a game that gave you eyes in the back of your head as an upgrade for a reason. Many a time, I looked down and struggled to look back up in time to react to what was going on aroind me. At the time, the speed also leaves much to be desired, and I think that’s a more important factor than you imply here: System Shock, as much as it is the “thinking man’s shooter” counterpart to Doom’s more action-driven gameplay, is still an action game. When you die because your computer isn’t good enough to run the game, the game ceases to be fun. Thankfully, on a modern system this is a non-issue.

Another big obstacle people don’t discuss in System Shock’s way was that Looking Glass were made to launch the floppy disk version of System Shock before the CD version. This seems innocuous enough, but the floppy disk version left notable omissions—most notably, voice acting. If you bought System Shock on launch from your local game store in 1994, you would barely hear SHODAN’s voice. The music was also downgraded. Given how much that adds to the game’s atmosphere, I can imagine it may have effected early evaluations of the game.

I still love it, but I know a few people who have found it utterly unplayable.

Jimmy Maher

March 19, 2021 at 9:53 pm

System Shock was developed at a time when the world hadn’t yet settled on a standard way of controlling these types of games. I’m not sure to what extent it’s truly clumsy and to what extent it can just *feel* that way to folks who have had the One True Modern Interface ingrained on their brains. I sometimes think I have an easier time with these old FPS-style games because I’ve never spent much time playing newer ones; I’m sure it will surprise exactly no regular readers if I reveal that it’s never been my favorite genre. I played the original System Shock for this article without any mouse-look patches or the like, so I can’t speak to how they change the experience. However, I would be slightly concerned that making such radical changes could wind up breaking the game Looking Glass intended. Again, though, I have no direct experience.

In my opinion, the best way to play the unpatched System Shock is with a flight-style joystick — a rather endangered gaming peripheral these days, I know. Set up your hat control to make you lean left and right and crouch up and down, and you’re getting somewhere. I suspect — I probably should have asked one of interviewees directly, but I never thought of it — that Looking Glass primarily envisioned joystick control.

System Shock definitely moves at a slower pace than DOOM, and to some extent this is due to programming limitations, but I do think there’s an element of design in there as well. I tend to play very slowly and tactically: sneaking my way to advantageous positions, leaning and crouching like crazy, etc., playing like a sniper. I’m not at all good at most action games, but I find that System Shock works pretty well for my play style. I’m certainly better at it than I am at DOOM. (Of course, there’s also the fact that I find the premise and aesthetics of System Shock more interesting and appealing, which could make me more willing to persevere with it…)

Steve McCrea

March 19, 2021 at 11:22 pm

There’s some discussion of the controls in the podcasts I linked to above. For example, explaining that mouse look only works when the framerate is above a threshold that these games don’t reach on contemporary hardware. Also, that the game auto-levels your view when you start moving to increase the framerate, since the texture mapping is faster when you are looking straight ahead, and mouse look would eliminate that speedup.

Nate Owens

March 20, 2021 at 1:02 am

The Enhanced Edition from a few years ago has a toggle between mouselook and mouse-interact that, while not exactly what a modern player would want, got the job done for me.

Joshua Barrett

March 20, 2021 at 3:10 pm

I’m a bit dubious about the game being designed with joystick in mind, simply because of the mouse dependency. However, while the controls are clunky, in that they make common rapid reactions (adjusting view, turning) laborious, I should also note that for 1994 they were actually quite innovative. SZXC functions as System Shock’s wasd, A and D turn, qwe leans, rfv adjusts your view, and tgb adjusts height. This is much, much closer to a modern control scheme than any other game of the time. It’s a clean, logical, memorable set of keyboard bindings which ensures keys for controlling every vital function are within two keys of movement, which is more than I can say for the keyboard controls that would arrive with the Build Engine games (ugh…) that popularized vertical look on the FPS side of things.

But while the interface does have its merits, the fact is that making turning and looking so difficult can make the game much more frustrating, even though the game very deliberately used that fact to build tension. Mouse look patches (which add a mouselook toggle, usually on e or f) don’t ruin the experience, in my opinion (I’ve played both with and without), but they do make thimgs different: The rear camera mod because useless, and combat is a little easier. On the whole, I’m glad it exists, because it makes a game that most modern players would balk at attempting infinitely more accessible.

wds

June 30, 2021 at 8:08 pm

Settled or not, System Shock had the worst interface of any game I’ve ever played. Looking Glass failed to understand that interface is a fundamental part of game design and gameplay, and that, if push comes to shove, the rest of the game design should be adjusted to fit an efficient and intuitive interface. SS was a pile of great ideas all thrown together with no regard for how the player would interact with any of those ideas, or how they would fit with each other, and the interface seems to have been a half-baked afterthought at best. The result is a downright unplayable mess. The Enhanced Edition is only barely playable.

I think where System Shock failed, though, Marathon succeeded. Unfortunately, those of us who weren’t on Macs had no idea what we were missing at the time.

minusf

March 19, 2021 at 11:24 pm

i am one of the few that always preferred the “mouse aim” instead of “mouse look” and i wish more companies experimented with this style of controls, after all we move our heads only when “turning”, not when aiming at something in front of us.

but of course having keys to move the head is slow, so maybe by having an “inner region” and an “outer region” of the viewport, where moving the mouse only in the “inner region” wouldn’t move the head only the crosshair and moving the mouse further out into the “outer region” would start turning the head :]

the first game to introduce to modern mouse look AFAIK was bethesda’s Terminator Future Shock one year later.

TM

April 2, 2021 at 8:06 am

“the first game to introduce to modern mouse look AFAIK was bethesda’s Terminator Future Shock one year later.”

In fact, Marathon already included mouse-look before that (it was released in December 94).

But mouse-look in FPS is even older, since it was found in The Colony in 1988 — however in that game it was only used on the horizontal axis; the vertical axis of the mouse was used to move forward/backward IIRC.

I guess in a way it made sense for mouse-look to first appear in Mac games. :-)

For those who have never heard of The Colony: it was an FPS in which you played a lone marshall exploring a space colony that was invaded (what a surprise!) by alien monsters — I don’t know how many times this idea was used and reused in the FPS world. :-D

Peter Olausson

March 19, 2021 at 9:22 pm

I love the way the “shock” in the name was resurrected in what’s been called it’s spiritual successor, Bioshock (2007). Especially because it was way more successful. Guess that story will be told here, eventually. :-)

Cheshire Noir

March 20, 2021 at 1:46 am

The game that made me fall in love with PC gaming. I’d had an Amiga up to this point (And quite a kickass one at that) so the PC was always a “work” system for me. Then I got System Shock on a system more than capable of playing it and that was it for me. Within 6 months I’d packed up the Amiga and gave it away.

I still play it regularly and kickstarted the (not so) recent reboot effort.

Fondest memory was playing it in a darkened room with my brother, creeping through a robot infested level, conserving ammo and being super-careful, when the wind blew the door closed behind us. We both screamed and I burned through a precious clip of slag rounds spraying in a 360 degree arc.

Also a game where the sequel was as good, if not better, but that’s a story for another day.

Tom

March 28, 2021 at 3:05 am

Yes! One of the scariest moments I experienced in System Shock was very similar. A stupid elevator door closing unexpectedly had me jumping out of my skin.

Andrew Pam

March 20, 2021 at 3:33 am

“at the every end” is a typo for “at the very end”.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that System Shock is sufficiently well remembered that it is now being remade with release due this year: https://store.steampowered.com/app/482400/System_Shock/

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/System_Shock_(upcoming_video_game)

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 8:01 am

Thanks!

Jon

March 20, 2021 at 3:56 am

“the System Shock engine outdoes DOOM in every sense but the admittedly important one of raw speed … None of this is true of DOOM; it’s peculiarly flat and regular spaces were designed to avoid many of the complications which System Shock tackles head-on.”

It’s difficult to take anything you say seriously when you write nonsense like this. Having worked directly with both, I know that System Shock’s environments are far more constrained than Doom’s in significant ways. System Shock’s engine, like Ultima Underworld’s, is based on a tile system, something patently obvious if you look at the map screenshot you’ve included in this article. This limits the levels to arrangements of these 64×64 unit tiles, and means that, unlike in the Doom engine, you cannot have walls at arbitrary angles, or spaces of arbitrary shape and size. Walls can only be perfectly straight or at a 45 degree angle. You cannot, for example, have a curved wall, or a spiked one, or really any kind of the kind of complex, large-scale and dynamic architecture you see in many Doom levels.

That’s not to say that the System Shock engine was primitive. It was not. It was a great technical achievement and did have numerous advantages over the Doom engine. But to claim it outdid id’s engines in every respect except performance is a deliberate, ahistorical lie. Doom, and the rest of Id’s output is not to your taste, that is something you’d made abundantly clear. But to allow that distaste to so warp your presentation of basic technical information is a total betrayal of your claim to be a digital historian.

System Shock was and is a great game. It doesn’t need someone trying to clumsily diminish the achievements of its contemporaries in order to be so.

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 7:59 am

Thanks! My understanding of the DOOM engine from The DOOM Black Book has obviously failed me somewhat, or my memory has. I’ve softened the wording of the comparison and acknowledged some of the affordances of the DOOM engine which I’d neglected. If you have any more suggestions of how to highlight the differences between the engines without getting too far down into the weeds, I would certainly appreciate it. I’m not a 3D-engine programmer, so these things can sometimes be a challenge for me.

Martin

March 20, 2021 at 6:09 pm

While not an engine design, really just a design feature, did System Shock implement the level files external from the code files (as in WAD files)? That extendability was something that took Doom to another level and the reason there are people still playing it now.

dmdr

March 23, 2021 at 4:26 am

“non-vertical walls”

presumably by this you mean something like ‘non-orthogonal walls’, since Doom’s walls are always vertical (no slopes, as you noted yourself). ‘Arbitrarily angled walls’ might be better.

Did Shock have lowering/raising floors or anything like that? I honestly don’t remember anymore, might be worth mentioning if it doesn’t (manipulating Doom’s floor actions is how you get the ‘dynamic architecture’ Jon mentioned above).

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2021 at 7:23 am

That is better. Thanks!

System Shock does have raising and lowering floors, assuming I’m understanding you correctly. Within the individual levels, there are freight-style “elevators” where you push a button to move them up and down whilst standing on top.

Aula

March 20, 2021 at 6:30 am

“but it in a more natural”

but in

“it’s peculiarly flat and regular spaces”

its

“the every end”

very

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 8:03 am

Thanks!

Mark Williams

March 20, 2021 at 11:23 am

I was never a great fan of the System Shock games, partly because they scared me! However I loved playing Terra Nova, despite its low resolution, and was disappointed it was never upgraded visually.

I also loved the Thief games, which in many ways perfected the approach to environmental problem solving you describe in this article.

Martin

March 20, 2021 at 2:48 pm

So can someone compare System Shock with Marathon (which only ran on the Mac)? I would have imagined that few would have experienced both together back in the 90’s but now they could be compared side by side.

Sounds like both that exploritory component in uncovering the real story that is taking place around you though I would guess that Marathon has more of a fighting component.

Owen C.

March 20, 2021 at 4:58 pm

Not sure if you are asking this as someone familiar with System Shock or as someone familiar with Marathon.

It’s true that both System Shock and Marathon have a lot of pieces of story found throughout the environment; mostly audio logs found on corpses in System Shock and computer terminals found throughout the levels in Marathon. Of particular note are the more cryptic terminals in out-of-the-way areas of Marathon whose meanings are still being debated by fans decades after the game’s release. Marathon arguably has a more complicated story than System Shock, especially the later games like Marathon Infinity with its bizarre narrative structure that hops between alternate realities. Also in spite of SHODAN’s memorable voice acting I think that Durandal is a more interesting rogue AI since he’s a bit more morally nuanced and you spend most of the series working for him.

Though outside of the greater emphasis on story and atmosphere, in terms of both game mechanics and engine Marathon is a traditional linear first-person shooter similar to Doom. System Shock was an early attempt at the immersive sim genre so you have a wider range of options like drugs and cyborg implants rather than only guns, and you have more variety in objectives like destroying cameras/computer cores and the hacking and cyberspace minigames. The exploration is also more open-ended where you can move freely between levels of the station rather than a strictly linear series of levels. It also uses a pretty different engine than both Doom and Marathon in terms of being tile based with sloping walls and floors.

While they are both interested in story and atmosphere, Marathon is mechanically similar to Doom so I feel like it’s the same as the System Shock/Doom comparison in the article, where they don’t really belong to the same genre so it’s comparing apples and oranges.

(For the record I was a fan of Marathon growing up but could never really get into System Shock 1 or 2. I love Thief and Deus Ex though)

Also quick correction in the article, it’s Terri Brosius not Terry

Martin

March 20, 2021 at 6:12 pm

I see Warren Specter was the game producer. So a game leading up to Deus Ex, huh. Interesting. Deus Ex is my favorite game ever BTW.

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 9:22 pm

Thanks!

Wade Clarke

March 22, 2021 at 1:32 am

The Marathon games are always pretty scary/atmospheric in the visceral sense. But I think what cements their aesthetic for me is the underlying feeling that you’re never entirely sure why you’re doing what you’re doing. Which is really interesting for a game with lots of intense action (interspersed with wandering creepy abandoned spaceships) and where, mechanically, you have concrete goals on each level. And this uneasiness is all down to the pure text dispensed by the AIs through the terminals. In feeling, it’s actually a pretty similar to how parser adventure games create unease with unreliable narrators, which is what the AIs are.

Durandal doesn’t present as rogue straight off, so you start in a relationship of trust, and potentially think of him along the lines of: ‘This is just the game telling me what to do on this level’. When he does start getting strange, you still have no choice but to fulfil his goals, and feel uneasy. Then other AIs start stepping in and saying ‘This AI is rogue, do what we say instead.’ At first this is experienced as a relief, or rescue. But having been shown you can’t accept what’s being dispensed by these terminals at face value, you never really do again, especially when the plot starts feeling abstract / hard-to-follow and you’re given conflicting orders. e.g. You’re now asked to help creatures you were told to shoot in earlier levels because a particular AI has aligned with them.

So you’re definitely a pawn in Marathon, and you’re given a rather mysterious view of what’s going on in the world framing yours, and I don’t think you ever feel certain about what’s going on out there. I certainly never felt particularly good or clear about what I’d done in Marathon after each level, plot-wise, as I never knew if it was really for the greater good. All I knew was that I survived.

Joshua Barrett

March 20, 2021 at 5:05 pm

Marathon did have a PC port…

Anyways, Marathon and System Shock are very, very different beasts. System Shock, for all its lack of a levelling system and its comparatively action-oriented personality, is still a successor to Ultima Underworld and firmly entrenched in the Looking Glass tradition of building environments that feel more like living places than game levels: Theme informs design, not the other way around. Citadel Station feels like a real station: it’s cramped because every inch is being utilized for something: space is limited, and can’t be wasted. At the same time, each level is lined with passages and interconnections to ensure that humans can quickly and easily navigate between locations. Shodan can’t move walls, so she prevents your free movement through passive means: locking doors, manipulating the ship security system. No matter how badly something is needed for gameplay reasons, I always *believe* that there’s a narrative reason for it because Looking Glass has made me trust that there will always be one.

Marathon is constructed more like a traditional FPS of the era. Levels do more to simulate real places than Doom, but they are still “game-ey.” Ultimately, Marathon’s plot happens to “people” who aren’t you. You serve as an incidental agent for the more important parties and occasionally getting glimpses of the bigger picture. System Shock’s narrative actually centers on you. Marathon is also more action-oriented than System Shock, which is a slower, more methodical, almost horror-inspired game. Although it is hampered by weapon design I’d characterize as suboptimal (Marathon, I mean).

Martin

March 20, 2021 at 6:21 pm

I thought on Marathon 2 was ported to the PC. Sure all three can be played on a pc now, but back in the 1990’s, …

Take the point about you not being in the middle of the events in Marathon though. That would provide a different playing experience.

Brian

March 21, 2021 at 2:49 pm

Thanks—came here to raise that. Durandal’s messages still echo in my memory. And boy do I remember the first time I was walking a bridge through a big room, chasms on both sides, when a Compiler drifted up next to me. I just about had a heart attack.

Oded

March 20, 2021 at 3:27 pm

Typo – “from Look Glass” should be “from Looking Glass”

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 4:53 pm

Thanks!

Iffy Bonzoolie

March 20, 2021 at 6:03 pm

Another random Infocom link to Looking Glass: Meretzky worked at Floodgate for a time, Neurath’s later studio. This was after the 90’s, so I guess a bit retroactive.

Who was the Infocom of the aughts?

Jimmy Maher

March 20, 2021 at 9:24 pm

I’m afraid I don’t know anywhere near enough about that era to say. Ask me again in fifteen years. ;)

Kevin Butler

March 23, 2021 at 4:49 pm

Well then, I stand corrected. My apologies on this one.

John

March 20, 2021 at 11:06 pm

Huh. I knew that Austin Grossman had written for various games, but I did not know that System Shock was one of them. His novel Soon I Will Be Invincible is one of my favorite books. I’m also quite fond of his second novel, You, which is about, among other things, game development and the history of the games industry. As you read along, it’s fun to speculate about which characters might correspond to which actual industry figures.

Alas, this is still not quite enough to get me to play System Shock. I played the demo once on the family PC back in the late 90s and, uh, let’s say it didn’t click with me.

Kai

March 21, 2021 at 4:21 pm

“So, there would no numbers in his next game” – missing a ‘be’, but I guess the duplicate ‘in’ in “the System Shock engine outdoes DOOM in in a number of” kinda evens it out.

Jimmy Maher

March 21, 2021 at 8:29 pm

Thanks!

Bmp

March 21, 2021 at 9:44 pm

When games have sophisticated writing, critics who prefer cerebral entertainment tend to overlook their gameplay weaknesses and overemphasize their strengths. Even given this, I think this article is a bit too unbalanced.

A reader who didn’t play any of these games would get the impression that System Shock is a flawless masterpiece that was not as successful as its rival Doom mostly because, due to its complexity, it was necessarily too demanding for the audience.

I’d argue against this. First, there are several weaknesses in System Shock’s gameplay that should be mentioned, and secondly, the comparison with Doom is rather biased.

I played and completed System Shock sometime in 2000-2010, after completing System Shock 2, and I enjoyed the game. But if I wanted to play a similar game today, I sure would like the level design and combat to be improved.

– If I remember correctly, the combat is boring a lot of the time because the player is able to control the situation too easily. You usually don’t need to engage more than 1 or 2 enemies at the same time. The different enemy types don’t force the player to use sufficiently different tactics – they can almost always be sniped around the corner. This is in contrast to Doom and especially Doom 2 with their huge variety of combat situations, due to the far more diverse level design and large monster variety.

– The level design in System Shock is rather monotonous both from a gameplay as well as from a visual perspective. It’s mostly cramped labyrinths. The game would have benefited a lot from Doom’s level design variety, which, in my opinion, far exceeded that of any other action game so far, due to the possibilities Doom’s engine gave its level designers. But even Ultima Underworld had more varied locations, in my opinion, not least due to the rivers and lakes.

– Player movement and controls are needlessly complex and fiddly and don’t feel half as good as Doom’s default controls and not one tenth as good as Doom’s mouse-look and keyboard combination. This can’t simply be excused due the game’s higher complexity – the user interface is just overloaded and poorly designed. It almost seems like Looking Glass’s more cerebral developers just didn’t have the intuition for smooth and intuitive movement controls, in a similar way as Ultima 8’s designers didn’t reach half of the movement feel as its inspiration Prince of Persia.

– System Shock has some advanced engine features, but I question how much benefit they actually bring to the game. The way the levels use slopes, to me they don’t seem to make much difference compared to stairs – and if as a level designer I could only choose one, I’d certainly choose stairs. System Shock has bridges (and Ultima Underworld already had them too – they’re sprite objects the player can stand on), which, granted, Doom would have benefited from. The lighting may be realistically simulated, but the level designer-controlled lighting in Doom sure seems to be used in far more impressive situations.

– Anyway, these advanced engine features are unimportant in light of the fact that System Shocks’s levels suffer enormously from the fact that they are rigidly tile-based, which Jon above already explained and which wasn’t even mentioned in the article despite its importance. This alone makes Doom’s levels so much more versatile and visually interesting that it’s really no contest.

– The claim about Looking Glass’s “aesthetic sophistication” is a bit vague, but regarding the visuals I’d say that System Shock is a bit drab and artistically merely decent. (Whereas, again, Doom established an iconic art style that can carry a whole subgenre.) And aside from the excellent voice acting, the sound effects pale to Doom’s growling demons searching for the player.

– What does “you must constantly use light and shadow” mean? Is there actually a practical way to sneak past enemies in the dark? I doubt it, as this claim was bandied about related to Ultima Underworld already, and it didn’t make much of a difference there either as far as I could tell. Generally, I don’t remember that I had to play in any kind of clever way to win System Shock, but maybe I’ve forgotten those parts.

– I always love it when gameplay is so good that it makes me want to re-play in a higher difficulty level (forcing me to play more tactically and more skillfully), or that it makes me want to continue playing with level expansion sets. That is very much the case with Doom, as anyone can see due to the sheer number of fan-made custom level sets on doomworld.com, proving the huge appetite for playing and for creating more levels. In contrast, the percentage of players who finish System Shock 1 or 2 and hunt for fan-made levels is far lower, I’d bet. There’s not this feeling that the official levels have merely scratched the surface of what is possible with the game features. The Thief games are two games where Looking Glass achieved this, though.

System Shock is still a great game (the sequel more so, IMO) and I’d like to play more well-made games in this genre. But if immersive sims are to be sufficiently commercially successful that they justify their development, it wouldn’t hurt to take a page out of Doom’s playbook.

A “vague sense of fatalism” because Doom “needed much less player education” and “was more likely to be commercially successful” is not exactly a suitable approach to make immersive sims competitive. Don’t underestimate the audience. But immersive sim developers shouldn’t limit themselves by bowing out of the competition with pure action titles when it comes to controls, combat, level design and fun gameplay flow.

For example, why the heck did the recent Prey limit its audience from the start by merely featuring fuzzy black shapes as enemies?

On a different note, for anyone who has completed System Shock I wholeheartedly recommend Shamus Young’s fan fiction book “Free Radical”, which is online here: http://www.shamusyoung.com/shocked/index.php

If you’re sceptical of the quality of a fan fiction work, maybe reconsider, as this book starts from the game’s premise and weaves a gripping story from start to finish, with a very cool ending. It’s worth it.

Mike B.

March 22, 2021 at 12:31 am

I could never get into System Shock. System Shock 2, on the other hand, was a masterpiece. Still a pretty decent game today with mods. Highly looking forward to the System Shock remake coming this summer.

Lars

March 22, 2021 at 11:23 am

The source code for the Mac/PPC version has officially been published on GitHub: https://github.com/NightDive-Studio

Unfortunately, It requires the Mac data specifically.

Petter Sjölund

March 25, 2021 at 12:28 am

The re-write for modern systems and PC assets is here: https://github.com/Interrupt/systemshock

Kevin Butler

March 23, 2021 at 3:40 pm

“…Three members of the band quickly agreed,…” Makes it sound like there are more members then three. To make it a better read, it probably should be “…The three members of the band quickly agreed,…”

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2021 at 4:25 pm

But there were more members than three. ;)

Nate

March 24, 2021 at 4:17 am

Is there a word missing in this quote? I don’t know how to parse it.

“We hope that our toiling now to make things work when it is still very hard to do effectively…”

Maybe “to do so effectively”?

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2021 at 7:47 am

That’s a direct quote from a published interview. It reads clearly enough to me, but mileages may vary…

Jonathan O

March 25, 2021 at 9:14 pm

“… is more advanced than the psuedo-3D of …” should be “… is more advanced than the pseudo-3D of …”

Jimmy Maher

March 26, 2021 at 7:53 am

Thanks!

Anton

March 26, 2021 at 1:19 pm

Well, it looks like you have triggered some sensitive Doom fans here. Personally I am extremely sad that everybody nowadays thinks id software and Doom were pioneers of FPS genre and overlook the fact that Ultima Underworld came earlier and had a lot of innovations that we take for granted today. But history has proven that, although Doom has better publicity, it is obvious that its path led nowhere – Half Life has practically killed Doom-style FPS, as developers try to incorporate better plots and immersion features nowadays, which is great IMHO.

stepped pyramids

March 30, 2021 at 3:16 pm

I think that’s overstated. Half-Life was built on a modified Quake engine, and the designers credit Doom as an inspiration. Quake multiplayer was massively influential on later games. The major non-Doom influence on modern FPS is Halo, anyway.

EG

April 9, 2021 at 9:54 pm

CS-GO is the most-played PC game on Steam; that would speak against the claim here, not to mention the entire genres based on death-match type online play. If you limit it to single-player experiences, sure.

McTrinsic

August 3, 2021 at 2:47 pm

System Shock was at least as revolutionary as it comes across in terms of immersion. I remember leaning in my chair to the left to look around a corner.

Of course the comparison to Doom is inevitable due to the release dates of both games an the initial similarity.

The best example for me that shows the difference is the skateboard-Stunt. Probably has a different name officially, but that’s what is for me. The situation is that you have some shoes with hover abilities. You can then use a slope to run down, gain speed and then jump over a chasm. You had tondo it like that. Standing on the edge of the chasm wouldn’t get you across. It’s this kind of pseudo-free exploration that leftist impression.

I also played Doom. And had fun with it. Was I impressed like that by Doom? No, I remember having fun going on a virtual rampage. That’s it. And the first real multiplayer-FPS. Seeing my colleague from the other PC on screen was impressive. Technically.

The complete package of System Shock still impressed me today. Level design is a Minor issue here for me.

Overall I would say both games target a different audience. Would you complain that there too much uninteresting dialogues and too much action if you decide to watch ‚Rambo 2’ ? You get what you expect and that’s well executed (for back then). Don’t compare it to ‚The Last Mohican‘ or whatever.

Wolfeye Mox

August 13, 2021 at 10:37 am

System Shock is one of those legendary games I never had the pleasure of playing when it first came out. I heard of it mainly because people mentioned it partly inspired BioShock, and that it’s an amazing game in it’s own right.

Now, I own it on GOG, both the original version and the enhanced edition, as well as the sequel… But, I’ve yet to play it. What?! I’ve got a huge backlog!

But, your article did make me bump it up a more than a few spaces to be near the top.

Game still looks good and playable, even after all these years. Guess that’s what made it a legendary classic. Shame it got called a Doom clone, and overshadowed, did those folks even play it? It’s got a whole different vibe, even with the first person POV. Oy vey.