I apologize for liking German generals. I suppose I ought not to.

— Desmond Young

When I attempted to play the SSI computer game Panzer General as part of this ongoing journey through gaming history, I could recognize objectively that it was a fine game, perfectly in my wheelhouse in many ways, with its interesting but not overly fiddly mechanics, its clean and attractive aesthetic presentation, and the sense of unfolding narrative and personal identification that comes with embodying the role of a German general leading an army through the campaigns of World War II. But for all that, I just couldn’t enjoy it. When I conquered Poland, I didn’t feel any sense of martial pride; all I could see in my mind’s eye were the Warsaw ghettos and Auschwitz. I found I could take no pleasure in invading countries that had done nothing to my own — invasions that were preludes, as I knew all too well, to committing concerted genocide on a substantial portion of their populations. Simply put, I could take no pleasure from playing a Nazi.

So, Panzer General prompted me to ask a host of questions about the way that we process the events of history, as well as the boundaries — inevitably different for each of us — between acceptable and unacceptable content in games. At the core of this inquiry lies a pair of bizarrely contradictory factoids. The Nazi regime of 1933 to 1945 is widely considered to be the ultimate exemplar of Evil on a national scale, its Führer such a profoundly malevolent figure as to defy comparison with literally anyone else, such that to evoke him in an argument on any other subject is, so Godwin’s Law tells us, so histrionic as to represent an immediate forfeiture of one’s right to be taken seriously. And yet in Panzer General we have a mass-market American computer game in which you play a willing tool of Adolf Hitler’s evil, complete with all the flag-waving enthusiasm we might expect to see bestowed upon an American general in the same conflict. If the paradoxical attitudes toward World War II which these factoids epitomize weren’t so deeply embedded in our culture, we would be left utterly baffled. For my part, I felt that I needed to understand better where those selfsame attitudes had come from.

I should note here that my intention isn’t to condemn those people whose tolerance for moral ambiguity allows them to enjoy Panzer General in the spirit which SSI no doubt intended. Still less do I want this article to come across as anti-German rather than anti-Nazi. The present-day population of Germany is still reckoning with those twelve terrible years in their country’s long and oft-inspiring history, and for the most part they’re doing a decent job of it. As an American, I’m certainly in no position to cast aspersions; if a different game had crossed my radar, this article might have been about the legacy of the American Civil War and the ongoing adulation in many American cultural corners of Confederate generals who fought for the privilege of continuing to enslave their fellow humans. As always here, my objective is to offer some food for thought and perchance to enlighten just a bit. It’s definitely not to hector anyone.

The occasional reports which reached the Allied countries of the horrors of the Holocaust during the early and middle years of World War II were widely dismissed, unfortunately but perhaps understandably, as gross exaggerations. But when American and British armies finally began to liberate the first of the concentration camps in late 1944, those reports’ veracity could no longer be denied. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied forces attacking Germany from the west, made it a point to bear witness to what had taken place in the camps. He ordered that all of his men should pass through one or more of them: “We are told the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, we know what he is fighting against.” Eisenhower also made special provisions for bringing journalists to the camps to record the “evidence of atrocity” for readers back home and for posterity.

After the war, the hastily convened Nuremberg trials brought much more evidence of the Holocaust to light, not just for the assembled panel of judges but for ordinary people all over the world; the proceedings were covered in great detail by journalists. But after the trials concluded in late 1946, with eleven defendants having been sentenced to death and a further seven sentenced to prison terms of various lengths, the Western political establishment seemed to believe the matter was settled, evincing a devout wish just to move on that was out of all keeping with the crimes against humanity which had been uncovered. To understand why, we need look no further than the looming Cold War, that next titanic ideological struggle, which had started taking shape well before the previous war had ended. Now that the Cold War was becoming an undeniable reality, the United States and its allies needed the new West Germany to join their cause wholeheartedly. There was no time for retribution.

A pernicious myth took hold at this juncture, one which has yet to be entirely vanquished in some circles. It lived then, as it still does to some extent today, because it served the purposes of the people who chose to believe in it. The historian Harold Marcuse names “ignorance, resistance, and victimization” as the myth’s core components. It claims that the crimes of the Holocaust were entirely the work of an evil inner cabal that was close to Hitler personally, that the vast majority of Germans — the so-called “good Germans” — never even realized any of it was happening, and that most of those who did stumble across the truth were appropriately horrified and outraged. But in the end, as the reasoning goes, they were Hitler’s victims as well, unable to do much of anything about it if they didn’t want to suffer the same fate as the people already in the concentration camps.

There were grains of truth to the argument; certainly the Gestapo was a much-feared presence in daily German life. But the fact remains that German resistance to Hitler was never as widespread as the apologists would like it to have been; every metric we have at our disposal would seem to indicate that the Nazi regime enjoyed broad popular support at least until the final disastrous year or two of the war.

The claim of widespread public ignorance of Hitler’s crimes, meanwhile, was patently absurd on the face of it. The Holocaust wasn’t a plot hatched in secret by shadowy conspirators; it was a massive bureaucratic effort which marshaled the resources of the entire state, from the secretaries who requisitioned the stocks of Zyklon B poison gas to the thousands of guards who tortured and killed the prisoners in the camps. Could the “good Germans” really not have seen the trains lumbering through their villages with their emaciated human cargoes? Could they really not have smelled the stench of death which rose over the concentration camps day after day? In order not to know, one would have had to willfully closed one’s eyes, nose, and ears if not one’s heart — which may very well have been the case for some, but is hardly a compelling defense.

Nevertheless, the myth of the ignorant, resistant, and victimized “good” Germans was widely accepted by the beginning of the 1950s. The Germans who had actually lived through the war had every motivation to minimize their complicity in the abominations of Nazism, while the political establishment of the West had no desire to rock the boat by asking difficult questions of their new allies against communism. The Holocaust was treated as vaguely gauche — a disreputable topic, inappropriate for discussion in polite company. To confront people with it was regarded as an act of irresponsible political agitation. In 1956, for example, when the French director Alain Resnais announced Night and Fog, a chilling 32-minute film which juxtaposed images of the concentration camps as they looked in that year with archival footage from the war years, the West German government lodged an immediate complaint with the French government, which in turned pressured the Cannes Film Festival into rejecting the movie as anti-German agitprop. The attitudes inculcated during this period begin to explain the existence of Panzer General so many years later, casting you cheerfully and with no expressed reservations whatsoever in the role of a German general of the Second World War.

The ugly truth behind Panzer General‘s glorification of Nazi aggression: a group of Polish prisoners are lined up against a wall and shot in the fall of 1939. Images like this one run through my mind constantly whenever I attempt to play the game.

But they aren’t a complete explanation, given that it would seem to be even harder to believe in the guiltlessness of German soldiers than civilians. The former were, after all, the ones who actually pointed the guns and pulled the trigger; their crimes would seem to be active ones, as opposed to the passive acquiescence of the latter. Even if they wished to claim that they personally had only pointed their rifles at enemy combatants, they couldn’t possibly plead ignorance of the horrifying crimes against noncombatants that were committed right under their noses by those all around them, right from the first weeks of the war. But, remarkably, a defense was mounted on their behalf, one that was similar in the broad strokes at least to that of the “good” German civilians.

The myth of the “clean Wehrmacht” held that the vast majority of German officers and soldiers were in fact no more guilty than the soldiers of the Allied armies. Most or all of the German war crimes, so the reasoning went, were the work of the dreaded SS Einsatzgruppen who traveled just behind the regular army units, maiming, torturing, raping, and massacring civilians in staggering numbers. Anecdotes abounded — some of them probably even true — telling how the ordinary German soldiers and their “professional” leadership had regarded their SS comrades with disgust, had considered them no better than butchers — cowards who preferred enemies that couldn’t fight back — and had shunned their company completely.

To be sure, the Einsatzgruppen were real, and did fill precisely the grisly role ascribed to them. But they were hardly the only German soldiers who murdered in cold blood. And, even if they had been, the fact that the ordinary soldiers found them unappealing doesn’t absolve them of blame for facilitating their activities. Note that the “ignorance” part of the “ignorance, resistance, victimization” defense has fallen away uncontested in the case of the German soldiers — as has, for that matter, the claim of resistance. All that’s left to shield them from blame is the claim of victimhood. Their country ordered them to carry out ethnic cleansing, we are told, and so they had no choice but to do so.

For all its patent weaknesses as an argument, the clean Wehrmacht would become a bedrock of a new strand of historical writing as well as a culture of wargaming that would be tightly coupled to it — the same culture that would eventually yield Panzer General. We can perhaps best understand the myth and its ramifications through the career of its archetypal exemplar, not coincidentally a wargaming perennial: Field Marshall Erwin Rommel.

Like Hitler, Rommel fought in the trenches during World War I, albeit as a junior officer rather than an enlisted man. He remained in the army between the wars, although his progress through the ranks wasn’t meteoric by any means; by 1937, when he published an influential book on infantry tactics, he had risen no higher than colonel. Having expressed no strong political beliefs prior to the ascension of Hitler, he became by all indications a great admirer of the dictator and his ideology thereafter. Although he never formally joined the Nazi party, he became close friends with Joseph Goebbels, its propaganda minister. “Yesterday the Führer spoke,” he wrote in a letter to his wife in 1938. “Today’s soldier must be political because he must always be ready to take action for the new politics. The German military is the sword of the new German worldview.”

That year Rommel was assigned personal responsibility for Hitler’s security. The Fūhrer, who had read his book and felt the kinship of their front-line service in the previous war, took as much of a shine to Rommel as Rommel did to him. On March 15, 1939, in the final act of German aggression prior to the one which would spark a world war, Rommel entered what was left of an independent Czechoslovakia at Hitler’s side; he would later take proud credit for having urged Hitler to push aggressively forward and occupy Prague Castle with a minimum of delay. He was promoted to major general shortly thereafter.

Rommel played a part in the invasions of Poland and then France and the Low Countries in the early years of World War II, winning the Knight’s Cross for his bold leadership of an armored division in the latter campaign. Then, on February 12, 1941, the newly promoted lieutenant general was sent to command the German forces in North Africa. It was here that his legend would be made.

Over the course of the next twenty months, Rommel led his outnumbered army through a series of improbably successful actions, punctuated by only occasional, generally more modest setbacks. Hitler promoted him to field marshal after one of his more dramatic victories, his capture of Tobruk, Libya, in June of 1942.

The North African front was a clean one by the standards of almost any other theater of World War II; it was largely a war of army against army, with civilians pushed to the sidelines. Thus it would go down in legend as “the war without hate,” a term coined by Rommel himself. This was war as wargamers would later wish it could always be: mobile armies duking it out in unobstructed desert terrain, a situation with room for all kinds of tactical give-and-take and noble derring-do, far removed from all that messiness of the Holocaust and the savagery of the Eastern Front. North Africa was never more than a secondary theater, the merest sideshow in comparison to the existential struggle going on in the Soviet Union — but it was precisely this fact that gave it its unique qualities.

Rommel’s men came to love him. They loved his flair for the unexpected, his concern for their well-being, and the way he stood right there with them on the front line when they engaged the enemy. More surprisingly, the soldiers he fought against came to respect him just as much. By early 1942, they had given him his eternal nickname: “The Desert Fox.” They respected him the way an athlete might respect a worthy and honorable player for the opposing team, respected not just his real or alleged tactical genius but the fact that he waged war with a scrupulous adherence to the rules that seemed a relic of a long-gone age of gentlemen soldiers.

The growing weight of Allied manpower and equipment following the entry of the United States into the war finally brought Rommel up short at the Second Battle of El Alamein in northern Egypt in October and November of 1942, forcing him to make a months-long retreat all the way to Tunisia. (Winston Churchill famously wrote about this battle that “before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein, we never had a defeat.”) Rommel was recalled to Germany in March of 1943, by which time North Africa had become a lost cause despite all of his efforts. The last German forces left there would surrender two months later.

In November of 1943, Rommel was placed in charge of the armies defending the coastline of France against the Allied counter-invasion that must inevitably come. By now, he was apparently beginning to entertain some doubts about the Führer. He flirted with a cabal of officers who were considering, as they put it, “extra-military solutions” to bring an end to a war which they now believed to be hopeless. Some of these officers’ discussions evolved into an attempted assassination of Hitler on July 20, 1944. The attempt failed; the bomb which Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg planted within the Führer’s headquarters caused much chaos and killed three men, but only slightly injured its real target.

There has been heated debate ever since about Rommel’s precise role in the conspiracy and assassination attempt. We know that he wasn’t present at the scene, but surprisingly little beyond that. Did he give the plan his tacit or explicit blessing? Was he an active co-conspirator, possibly even the man slated to take the reins of the German state after Hitler’s death? Or did he have nothing whatsoever to do with it? The temptations here are obvious for those who wish to see Rommel as an exemplar of moral virtue in uniform. And yet, as we’ll shortly see, not even his most unabashed admirers are in agreement about his involvement — or lack thereof — in the plot. There’s enough evidence to pick and choose from to support almost any point of view.

At any rate, Rommel had much else to occupy him at that time; the D-Day invasion had come on June 6, 1944. Three days before the assassination attempt, while he was out doing what he could to rally his overstretched, outnumbered army of defenders, his staff car was strafed by Allied fighters, and he was seriously wounded. Thus he was lying in hospital on the fateful day. Although he was not suspected of having been one of the conspirators for quite some time thereafter, Hitler had been none too pleased with his decision to fall back from the beaches of Normandy, ignoring express orders to fight to the death there. For this reason, Rommel would never return to his command.

Three months after these events, after having conducted dozens of interrogations, the Gestapo had come to suspect if not know that Rommel had been involved in the assassination plot at one level or another — and such a suspicion was, of course, more than enough to get a person condemned in Nazi Germany. Two officers visited him in his home and offered him a choice. He could commit suicide using the cyanide tablets they had helpfully brought along, whereupon his death would be announced as having come as a result of his recent battle injuries and he would be buried with full military honors. Or he could be dragged before the People’s Court on charges of treason, which would not only mean certain death for him but quite probably death or imprisonment for his wife and two children as well. Rommel chose suicide, thus putting the crowning touch on his legend: the noble warrior who makes the supreme sacrifice with wide-open eyes in order to spare his family — a fate not out of keeping with, say, a hero of the Iliad.

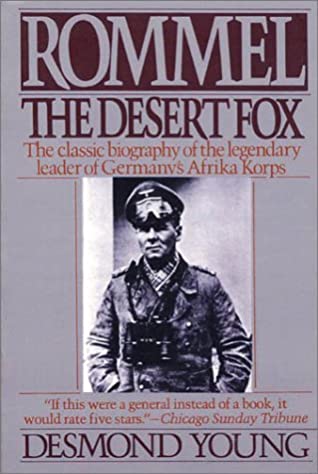

The book which, more than any other, is responsible for cementing the vision of an heroic, noble Rommel in the popular imagination.

For all that Rommel’s story perhaps always had some of the stuff of myth about it, his canonization as the face of the clean Wehrmacht was by no means always assured. It is true that, during his period of greatest success in North Africa, a mystique had begun to attach itself to him among Allied journalists as well as Allied soldiers. After his defeat at the Second Battle of El Alamein, however, the mystique faded. Few to none among the Allied brass were losing sleep over Rommel before the D-Day landings, and The New York Times mentioned his eventual death only in passing, referring to him only as a “Hitler favorite,” making no use of his “Desert Fox” sobriquet. At war’s end, he was far from the best known of the German generals.

The man responsible more than any other for elevating Rommel to belated stardom was a Briton named Desmond Young, a journalist by trade who saw combat in both world wars and somehow still managed to retain the notion that war can be a stirring adventure for sporting gentlemen. In June of 1942, while serving as a brigadier in charge of public relations for the Indian divisions fighting for the Allies in North Africa, he was captured by the Germans, and had a passing encounter with Rommel himself that left an indelible stamp on him. Ordered by his captors to drive over with them and negotiate the surrender of another Allied encampment which was continuing the fight, he refused, and the situation began to grow tense. Then Rommel appeared on the scene. Young:

At this moment a Volkswagen drove up. Out of it jumped a short, stocky but wiry figure, correctly dressed, unlike the rest of us, in jacket and breeches. I noticed that he had a bright blue eye, a firm jaw, and an air of command. One did not need to understand German to realize that he was asking, “What goes on here?” They talked together for a few seconds. Then the officer who spoke English turned to me. “The general rules,” he said sourly, “that if you do not choose to obey the order I have just given you, you cannot be compelled to do so.” I looked at the general and saw, as I thought, the ghost of a smile. At any rate, his intervention seemed to be worth a salute. I cut him one before I stepped back into the ranks to be driven into captivity.

From that one brief, real or imagined glance of shared understanding and respect stemmed the posthumous legend of Erwin Rommel. For in 1950, Young published a book entitled simply Rommel, a fawningly uncritical biography of its subject in 250 breezy pages. Even as he emphasized Rommel’s chivalry, courage, and tactical genius at every turn, Young bent over backward to justify his willingness to serve the epitome of twentieth-century evil. One passage is particularly amusing for the way it anachronistically places Rommel’s avowed support for Hitler into a Cold War, anti-communist context, revealing in the process perhaps more than its author intended.

Like ninety percent of Germans who had no direct contact with Hitler or his movement, he [Rommel] regarded him as an idealist, a patriot with some sound ideas who might pull Germany together and save her from Communism. This may have seemed a naïve estimate; it was no more naïve than that of many people in England who saw him as a ridiculous little man with a silly mustache. Both views were founded in wishful thinking. But the Germans, having had a bellyful of defeat and a good taste of Communism, at least had some excuse for believing what they wished to believe.

Only one component of the full legend of Rommel as it is known today is missing from Young’s hagiography: Rommel, said Young, “had never been a party to the [attempted] killing of Hitler, nor would he have agreed to it.” He had rather been the loyal soldier to the end, right down to his swallowing of the final poison pill.

Rommel became a success out of all keeping with any normal military biography upon its publication in Britain, then an equally big bestseller in the United States upon its publication there one year later. Some historians and thoughtful reviewers pointed out the problematic aspects of Desmond Young’s unabashed hero worship, but their voices were drowned out in the general acclaim for what truly was an entertaining, well-written, even oddly endearing little book. In the end, it sold at least 1 million copies.

Its initial success in Britain was such that Hollywood rushed a movie into production before the book had even made it across the Atlantic. Wanting to get the film out quickly, before the Rommel craze had run its course, 20th Century Fox didn’t have time to stage much in the way of battle scenes; the filmmakers would later admit that a closing battlefield montage of old newsreel footage was inserted in the hope that viewers would leave the theater thinking that “they have seen a lot more action and battle stuff than they actually have.” Rommel was played by stolid leading man James Mason; he and all of the other German characters spoke American English with the flat Midwestern enunciation so typical of the Hollywood of that period.

Although it hewed closely to Desmond Young’s book for the most part, the movie did make one critical alteration: it postulated that Rommel had turned definitively against Hitler late in the war and, after a long internal struggle over whether it was honorable to do so, had joined the assassination plot. This change was made not least because, even in this period of reconciliation and letting bygones be bygones, studio executives were nervous to release a film that made a hero out of a man who had died an unrepentant Nazi. But on the other hand, a repentant Nazi who saw the light, took action against evil, and died for having done so was, as the film’s screenwriter put it, a downright “Shakespearean” protagonist. From now on, then, this generous interpretation too became an integral part of Rommel’s legend.

Desmond Young, who served as an advisor for the film, didn’t seem overly bothered by its departures from what he believed to be the real circumstances surrounding the death of Rommel. In fact, to capitalize on what future generations would have called the marketing synergy between his book and the film, later editions of the former picked up a new subtitle: The Desert Fox.

The film proved a big hit, on much the same terms as the book: widespread popular acclaim, accompanied by the merest undercurrent of concern that a Nazi general might be less than entirely worthy of such full-throated approbation. Among the most strident of the critical voices was the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council:

We regard this film as a cruel distortion of history, an affront to the memory of the brave soldiers of all allied nations, a gratuitous insult to the free peoples who spent their strength and their substance to save a world from engulfment by Nazism. There is only one major villain in this picture: Hitler. The audience is asked to believe that only he was both a buffoon and an evil man; that the soldier Rommel — and other German generals — were military men, without “political” aims or motivations, carrying out orders. The world knows that totalitarianism infects the whole body politic of a nation, that neither fascism nor communism can be sustained except with the active collaboration in its depravity of politicians, diplomats, and generals — especially generals. To depict Rommel as less than such an active collaborator in Nazism is to twist history beyond recognition.

In 1953, the final building block of the legendary Rommel fell into place when the British historian and military theorist B.H. Liddell Hart published a book called The Rommel Papers. Hart was himself a complicated, vaguely pathetic character. At the end of the Second World War, he had been in nearly complete disgrace, having been one of the primary architects of the Allies’ disastrous would-be defense of France against the German invasion of 1940, a classic example of trying to fight the last war — in this case, imagining a repeat of the static trench battles of the First World War — rather than reckoning with the realities of the current one. But in the years that followed, he rehabilitated his reputation by latching onto some of his old writings from the 1920s, when he had been at least occasionally an advocate for a more mobile approach to warfare. Hart befriended many of the surviving German generals — often by visiting them in their prison cells — and bolstered his case via a tacit quid pro quo that would have gone something like this if anyone had dared to speak it aloud: “Say that you developed Blitzkrieg warfare by reading my old texts, and I’ll use my influence to promote the position that you were only a soldier following orders and don’t deserve to die in prison.” Being friendly with Desmond Young, Hart convinced the latter to include another assertion of his influence in his biography of Rommel: Rommel, wrote Young, had before the war “studied the writings of Captain Liddell Hart with more attention than they received from most British senior officers.” This was completely untrue; Rommel probably never even heard of Hart during his lifetime.

Be that as it may, Hart definitely did ingratiate himself with the general’s widow Lucia and his son Manfred after the war was over, and enlisted their aid for his own book about Rommel. The Rommel Papers proved a shaggy, unwieldy beast, combining together the following, presented here in order of historical worthiness: 1) what existed of a memoir which Rommel had been writing during the months of limbo that preceded the demand that he commit suicide; 2) a selection of Rommel’s wartime letters to Lucia; 3) Manfred Rommel’s recollections of the circumstances of his father’s death; and 4) Hart’s own oft-extended footnotes, “clarifying” and embellishing the other texts. Hart wrote of Rommel that “he was a military genius — more so than any other soldier who succeeded in rising to high command in the war.” He then went on to make the cheeky claim — writing of himself in the third person, no less! — that Rommel “could in many respects be termed Liddell Hart’s pupil” in the science of mobile, mechanized warfare. Meanwhile Manfred Rommel, who would go on to a long and fruitful political career, was almost as transparently self-serving in writing that his father had definitively “broken” with Nazism by 1943 and “brought himself, from his knowledge of the Führer’s crimes, to act against him.”

The Rommel Papers was another big success, its sales figures more than sufficient to drown out anyone who voiced concern about its editor’s patent lack of objectivity. The man who had for a time been Hitler’s favorite general was now firmly ensconced as an odd sort of folk hero in the postwar democratic West.

We’ll return to our examination of how this romantic figure paved the way for the likes of Panzer General momentarily. Before we do that, though, it might be worthwhile to examine the sustainability of this version of Rommel’s life story. We can boil our skepticism down to two questions. Was Rommel really all that as a general? And what is his true moral culpability for the role he played in the Second World War?

The first question is, if not exactly straightforward to answer, at least somewhat less fraught than the second. Rommel’s primary asset, many students of military strategy now agree, was his sheer boldness rather than any genius for the intricate details of war. Throughout his career, he had the reputation of a maverick, born of a willingness to disobey orders when it suited him. And as often as not, his seemingly reckless gambits caught his enemies off-guard and wound up succeeding.

But Rommel certainly had his weaknesses as a battlefield tactician, as even many of his biggest fans will reluctantly acknowledge. The greatest of them was probably his complete disinterest in the logistics of war. Rommel made a regular habit of outrunning his supply chains in North Africa. “The desert,” he said, “is a tactician’s paradise and a quartermaster’s hell” — but he did nothing to make his quartermaster’s job easier. When his army ran out of fuel or bullets, he started by blaming his subordinates, then moved on to blaming the Italian navy, which was in fact delivering more supplies than his army actually required most days, only to watch them pile up on the wharves of the Middle East’s port cities for want of a way to transport them inland to an army that had burrowed too deeply too quickly into the enemy’s territory.

Rommel’s men may have loved him, but his peers in the hierarchy of the Wehrmacht had little use for him for the most part, considering him a glory hound whose high-profile commands were mostly down to his friendship with Joseph Goebbels. They pointed out that his much-vaunted habit of standing with his men on the front lines during battles, pistol in hand like a latter-day Napoleon, made it impossible for him to observe the bigger tactical picture. There was a reason that most other generals of the war stayed in their headquarters tents well back from the front, right next to a junction box of telephone cables — and this reason had nothing to do with personal cowardice, as some Rommel boosters would have you believe.

Len Deighton, a well-known author of military fiction and nonfiction, writes bluntly in Blood, Tears and Folly, his recent revisionist history of World War II, that “Rommel was not one of the war’s great generals,” calling him “more adept at self-publicity than skillful in the conduct of warfare.” He credits much of Rommel’s success in North Africa to the German signals-intelligence service, which tapped into most of the principal Allied communication networks. (To be fair, Rommel’s opponents would be given an even more complete picture of his own plans and movements before the North African war was over, once the Enigma code breakers fully came into their own.)

In the end, then, we can say that Rommel possessed a remarkable ability to inspire his men combined with no small measure of battlefield audacity, but that these strengths were offset by a congenital unwillingness to sweat the details of war and an inability to play well with others as part of a joint military operation. The degree to which his strengths outweighed his weaknesses, or vice versa, must inevitably be in the eye of the beholder. We can say with certainty only that the North African theater, which gave his audacity such a sprawling blank canvas to paint upon and which allowed him nearly absolute authority to do whatever he liked, was the perfect place to make a legend out of him. Fair enough. What of the other, still thornier question of Rommel’s moral culpability?

The linchpin of the absolution which Desmond Young, Liddell Hart, and so many others since them have given Rommel is that he was simply a professional soldier obeying orders as he had sworn to do, all while remaining studiously apolitical. As we’ve already seen, this doesn’t quite jibe with the facts of the case: prior to 1943 at least, Rommel was a personal friend of Goebbels and an enthusiastic follower of Hitler, and plainly stated before the war that he considered it a good soldier’s duty to be political. But let’s accept the premise on its own terms for the moment at least, and see what else we can make of it.

On a strictly legal basis, “I was just following orders” is far from a cut-and-dried defense. Most codes of military justice state explicitly that a soldier is obligated not to follow an order which violates international laws to which his country is a signatory, such as the Geneva Convention. When Rommel led an armored division into France in 1940, the Einsatzgruppen traveled behind it. The fact that Rommel may have been made personally uncomfortable by their actions, may have made a conscious or unconscious decision not to witness them, may even have managed to avoid having similar units attached to his army in North Africa, doesn’t absolve him of guilt any more than it does any other German soldier who was a knowing accomplice to atrocity.

But then, legalistic arguments are inadequate if we really want to get to the heart of the matter. Rommel’s actions in Czechoslovakia, in Poland, in France, and elsewhere in Europe led directly to the murder of millions of Jews. And had the “war without hate” in North Africa ended in German victory, the ethnic hatred of his Nazi masters would have made its presence felt there too soon enough. I believe that a human being has a higher moral duty that transcends jurisprudence and the military chain of command alike. Surely it ought to be eminently noncontroversial to say that being a party to genocide is categorically wrong. I don’t pretend to know what I would have done in Rommel’s situation, but I do know what would have been the right thing to do. Leading genocidal armies of conquest with the excuse that such is one’s “duty” as a soldier strikes me as moral cowardice rather than its opposite. I hope that we can someday live in a world free of the sort of didactic thinking that is still used far too often to excuse Rommel for doing so.

But you are of course free to make your own judgments on these questions; these are merely my opinions, which I present by way of explaining why I don’t wish to deify Erwin Rommel and why Panzer General‘s glorification of his ilk makes me feel so queasy.

“It is well that war is so terrible,” said Robert E. Lee, famously if apocryphally. “Otherwise we would grow too fond of it.” New Yorker profile writer Larissa MacFarquhar struck a similar note from the opposite direction in a recent interview:

People who are pacifists always talk about how terrible war is because it is so bloody and violent and wasteful. What they’re not getting is that people who like war — or don’t dislike war — admit all that; they know all that. It’s very obvious, but for them it’s worth it because of the stimulation, as they see it, to human greatness.

I cannot hope to solve the puzzle of humanity’s eternal attraction to war despite the suffering and death it brings. I can note, however, that one way to enjoy the good aspects of war without all that pesky suffering and dying is to wage it in the imagination rather than in physical reality. Once the political questions which wars decide have been settled and the casualties have been tallied and mourned, we can fight the conflicts of yore all over again in our imaginations, milking them for all of the drama, heroism, and adventure that may have been obscured in the moment by their other horrifying realities. Desmond Young, Liddell Hart, and their fellow travelers embraced this idea enthusiastically during the middle of the twentieth century, and in doing so founded what amounted to a whole new genre of books: the popular military history.

Many more broad-minded historians came to hate this new class of writers for their willingness to wave away the truly important aspects of history. Military historians, they complained, insisted on viewing war as a sport (American football and cricket were common metaphors) or a game (chess tended to be the point of comparison here), all whilst ignoring their causes and effects on the broader scale of human civilization — not to mention the many pivotal changes in the course of human history that have had nothing to do with wars and battles. Some went so far as to claim that the military historians weren’t writing proper histories at all, but merely escapist entertainments, the equivalent of romance novels for the middle-aged men who consumed them.

Personally, I wouldn’t put it quite so strongly, any more than I generally rush to criticize anyone for his choice of reading materials. It seems to me that military history can be educational and, yes, enjoyable, but one does have to be aware of its limitations. It provides a window into only a single, very specific area of human experience. Its obsessive interest in how wars were fought at a granular level leaves unanswered more important questions about why they were fought and how the world changed in their aftermath.

Nevertheless, military history has been the dominant face of popular history in the West ever since Desmond Young and Liddell Hart wrote about Erwin Rommel. By the 1990s, the “Military History” shelf of the typical bookstore was twice as large as all the rest of its history section put together. Authors like Stephen Ambrose sold millions of books with their vivid depictions of combat on land, in the air, and at sea, even as cable-television stations like The History Channel reran the greatest battles of World War II on an endless loop. Needless to say, the legend of the noble warrior Erwin Rommel featured prominently in all of this. One particularly overwrought television documentary, for example, labeled him “the last knight,” and concluded with these words: “Erwin Rommel, soldier, was laid to rest in the village cemetery of Herrlingen. It planted back into the soil of a disgraced Germany at least one seed of honor and decency for a new flower.” (Perhaps the romance-novel charge does have some merit…)

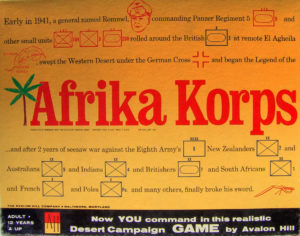

The first release of Afrika Korps. It’s telling that the game is named after Rommel’s army in North Africa, not the Allied one.

In the same year that The Rommel Papers were published, a correspondent for The Irish Times attended an odd museum exhibition in London that was devoted to Rommel’s exploits. He wrote the following afterward:

One fact was impressed upon me: that there is a strategy of warfare which, for the devotees, has little to do with blood and horror and death. The maps were being scrutinized like precious works. There was the impression that war was an enthralling game, like cricket. Viewing Rommel in this sense, I concluded that I had as much right to make a judgment as a professional footballer at a modern-art exhibition.

If military history approached war as a metaphorical game, then why not turn it into a literal game? After all, what could be better for a military-history buff than to live out the conflicts that had heretofore existed only within the pages of his books and try out alternate strategies? In 1954, Charles S. Roberts published a board game called Tactics through his new Avalon Hill Game Company. The canonical first commercial wargame ever, it depicted warfare in a somewhat abstracted, non-historical context. But six years later, Roberts and his company surfaced again with Gettysburg, the first wargame to engage with an historical conflict. Going forward, not all readers of military history would be wargamers, but all wargamers would be readers of military history.

Avalon Hill released a steady trickle of games over the next few years, most of them depictions of other battles of the American Civil War, the only conflict that even approached the popularity of the Second World War among American military-history readers. But by 1964 sales figures were trending in the wrong direction. Seeking to reverse the slide, Roberts shifted his focus to World War II, designing what would prove to be one of his company’s biggest and most iconic games of all.

As the name would imply, Afrika Korps dealt with the North African theater of the war, giving armchair generals a chance to step into the smartly shined boots of Erwin Rommel: “Now the legend of the Desert Fox is recreated!” trumpeted the box text. The game established several precedents. First, it made the North African front into a perennial favorite with wargamers for the same reasons that it was so popular with military-history authors and their readers: its wide-open terrain and the resulting room for tactical maneuvering, and its supposedly sporting, gentlemanly nature. Second, it taught many who played it that the Germans were simply cooler: they had better technology, better esprit de corps, even better uniforms than the stodgy Allies to offset their generally inferior numbers. And finally, it introduced the wargame cliché of the “Rommel unit”: a unit whose commander is such a superhero that he can break the rules that usually govern the game by sheer force of will. As a whole, notes Joseph Allen Campo in his recent PhD thesis on cultural perceptions of Rommel, “the focus on Rommel and more generally the German side (many wargames feature prominent German military motifs and use German military nomenclature) cater to a genre that customarily finds more interest in playing the underdog, relying on [the player’s] brains rather than overwhelming force, and accepting the challenge of reversing the historical result.”

Coincidentally or not, tabletop wargaming grew in popularity by leaps and bounds after the release of Afrika Korps. At its peak in 1980, the industry sold 2.2 million games.

I hope that the chain of causation and influence which brought us Panzer General thirty years after Afrika Korps is becoming clear by now. I won’t belabor it unduly, given that I’ve already told most of the story in other articles. Suffice to say that in 1979 an avid young tabletop wargamer named Joel Billings decided to found a company to bring his hobby to the personal computers that were just entering the marketplace at that time. That company, which Billings called Strategic Simulations, Incorporated, specialized in digital wargames for much of its existence, and was the very same one which brought Panzer General to store shelves in 1994.

The gallant panzer general gets his orders. (How can you argue with cool uniforms like these?) The game studiously avoids swastikas. In popular culture, the swastika has come to stand for the Gestapo, SS, and other “bad” Nazis, while the older iconography of the Iron Cross or eagle wings stands in for the “clean” Wehrmacht. But the real distinction is, as we’ve seen, less clear-cut than many would like it to be.

Erwin Rommel is never mentioned by name in Panzer General, but his larger-than-life persona of legend is stamped all over it. He is, after all, the personification of the Wehrmacht as wargamers know it — not as barbaric invaders and espousers of a loathsome racist creed which they are all too eager to use to justify genocide, but as clever, audacious, courageous warriors with great fashion sense and all the best kit. Afrika Korps: “You can re-create Field Marshall Rommel’s daring exploits at Bengasi, Tobruk, El Alamein, and points in between!” Panzer General:

Imagine that you are the Panzer General. You are the brightest and best of the new Axis generals in the Second World War. Go from triumph to triumph, invading and seizing the capitals of Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and ultimately the United States of America on your way to conquering the whole world!

In terms of the broader culture — the one that doesn’t tend to read a lot of military history or play a lot of wargames — Panzer General was already an anachronism in 1994. In 1960, the American journalist William L. Shirer had published The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, which over the course of its 1200-plus pages documented in meticulous detail exactly what the Nazi regime had done and how it had done it. Close on that book’s heels, the capture and trial of Holocaust administrator Adolf Eichmann in an Israeli court consumed the world’s attention much as the Nuremberg trials had a decade and a half previously — only now television brought the proceedings, and the atrocities they documented, to a much more visceral sort of light. In West Germany, the student activism of the hippie era, accompanied by the election of a social-democratic chancellor who was less beholden to the tradition of forgetfulness, finally pushed the country toward a proper reckoning with its past. A spate of unsparing books, films, and even museums about the Holocaust and the other crimes of the Nazi regime appeared in West Germany and elsewhere in the years that followed, fully acknowledging for the first time the complicity of those Germans who weren’t in Hitler’s inner circle. A new understanding became palpable among Germans: that they couldn’t escape from their past by denying guilt and wishing atrocities away; that the only way to ensure that something like the Third Reich never took root again was to examine how they themselves or their parents, living in a nation as civilized as any other in Europe, could have been tempted down such a sickening path.

These developments were as welcome as they were necessary, both for Germans and for all of the other citizens of the world. Yet Panzer General and the cultural milieu that had spawned it remained caught in that strange interregnum of the 1950s, as do most of the wargames of today.

So, having now a reasonable idea of how we got to this place where patriotic Americans bought a game in which they played the role of genocidal foreign conquerors of their country’s capital, it’s up to each of us to decide how we feel about it. What sorts of subject matter are appropriate for a game? Before you rush to answer, ask yourself how you would feel about, say, a version of Transport Tycoon where you have to move Jews from the cities where they live to the concentration camps where they will die. If, as I dearly hope, you would prefer not to play such a game, ask yourself what the differences between Panzer General and that other game really are. For your actions in Panzer General will also lead to the deaths of millions, at only one more degree of remove at best.

Or am I hopelessly overthinking it? Is Panzer General just a piece of harmless entertainment that happens to play with a subset of the stuff of history?

It’s a judgment call that’s personal to each of us. For my part, I can play the German side in a conventional wargame easily enough if I need to, although I would prefer to take the Allied side. But Panzer General, with its eagerness to embed me in the role of a German general goose-stepping and kowtowing to his Führer, is a bridge too far for me. I would feel more comfortable with it if it made some effort to acknowledge — even via a footnote in the manual! — the horrors of the ideology which it depicts as all stirring music and proudly waving banners.

Before I attempt to say more than that, I’d like to look at another game released the same year as Panzer General, designed by a veteran of the same wargaming culture that spawned SSI. It takes place in a very different historical milieu, but leaves us with some of the same broad questions about the ethical obligations — or lack thereof — that come attached to a game that purports to depict real historical events.

(Sources: the books Adenauer’s Germany and the Nazi Past by Norbert Frei, Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in Two Germanys by Jeffrey Herf, War Stories: The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany by Robert G. Moeller, Rommel: The Desert Fox by Desmond Young, The Rommel Papers by B.H. Liddell Hart, In Hitler’s Shadow by Richard J. Evans, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001 by Harold Marcuse, Blood, Tears, and Folly: An Objective Look at World War II by Len Deighton, War Without Hate: The Desert Campaign of 1940-43 by John Bierman and Colin Smith, The Real War (1914-1918) by B.H. Liddell Hart, Uncovering the Holocaust: The International Reception of Night and Fog by Ewout van der Knaap, and The Complete Wargames Handbook by James F. Dunnigan. But my spirit guide and crib sheet through much of this article was Joseph Campo’s superb 2019 PhD thesis for UC Santa Barbara, “Desert Fox or Hitler Favorite? Myths and Memories of Erwin Rommel: 1941-1970.”)

Alberto

November 20, 2020 at 7:02 pm

A very interesting article! Your reflections resonate with me as I found myself unable to play “Codename: Panzers” because the idea of destroying Polish and Soviet cities was too disturbing.

Somehow, however, I do not get the same feelings with Panzer General. Maybe because I played it since I was a very young kid almost unaware of history, maybe because the game is more abstract and one can delude theirselves in thinking to play, like another reader said, a sort of Napoleonic army with XX century technology. The human psyche is complicated.

I do not know if you plan to cover them, but the games by Paradox Interactive might deserve a mention in this topic. Even now there is a discussion on Reddit about why the developers chose to leave the Holocaust and the strategic bombing out of their game “Hearts of Iron”, but included other crimes like Stalin’s Great Purge inside the game mechanics.

Avian Overlord

November 22, 2020 at 7:00 pm

At least for Paradox, one factor there is that depicting the Nazi regime’s symbolism or atrocities in a game is illegal in a lot of places. The irony of course being that laws meant to avoid the glorification of horrors lead to those same horrors being whitewashed out of the record. But then, that’s pretty much always what censorship results in.

Gnoman

November 23, 2020 at 5:14 am

Strategic bombing is not left out of the Hearts Of Iron games. It is a mission type that can be assigned to any air unit with sufficient bombing capability. It doesn’t get much highlight not least because the nations with enough industry to do it well can usually steamroller any other nation.

Avian Overlord

November 24, 2020 at 4:28 am

Terror bombing is however absent. I suspect that’s more because it didn’t work though.

Alberto

November 24, 2020 at 2:58 pm

Yes, my memory was imprecise: specifically anti-civilian bombing is what Paradox did not implement. The developers prohibit even to mention it in their forums, alongside other war atrocities: s. https://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/threads/read-this-first-terror-bombing-concentration-camps-swastikas.266180/ (the same notice is repeated for the newer releases of HoI).

Avian Overlord

November 27, 2020 at 6:17 pm

As for mentioning Paradox, we’re still four years away from EU1. Still, they’ve become enough of a presence recently that I’d expect them to show up on the blog once we hit 2000.

Jason Dyer

November 20, 2020 at 7:33 pm

I tend to think back to actual wargames (as in, ones done by the military) in such situations. There was a group that figured out best tactics for taking out Nazi U-Boats, and of course, someone had to play as the Nazis. Does that mean the person in that role is actively taking on the morality and goals of the Nazis? No, the opposite: they are helping actively search for ways to defeat them.

If there’s sufficient abstraction, that’s the mode I feel like I’m playing the game in.

Have you played the follow-up, Allied General? It’s basically the same game but with Allied campaigns.

Having said all that, I general prefer just playing Starcraft and neatly evading all the historical stuff altogether.

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 8:23 pm

I have tried Allied General, but didn’t find it super-compelling. I understand from the fans of the series that it’s not that highly regarded. Perhaps the Germans really just *are* more fun to play — if you can construct the appropriate moral vacuum, of course.

Your preference for playing wargames set in worlds of space opera or fantasy does resonate with me. I generally like games that engage with the real world in some way, but I don’t really like to do so in terms of battles and wars and violence. Master of Orion and Master of Magic are just fine for that purpose.

Anonymous

November 20, 2020 at 9:04 pm

Inspired by your Master of Magic article, I found myself playing the game as a Chaos/Death wizard and found myself thinking along the same lines while the computer was playing its turns. Is it so important to be the Master of all Magic that you have to turn the world into a volcanic wasteland to get there? It seems like the Nature/Life combo has at least some moral authority. Sure, they are mercilessly slaughtering their enemies, but at least the world is a green paradise in the aftermath.

I always felt at least a little bit guilty about playing the later entries in the Civilization series because you can explicitly choose Slavery as a way to run your empire (if only temporarily) and it’s often more effective that trying to rush towards republic or democracy technologies. It’s also a little weird to play Russia as Stalin or China as Mao. I suppose that being able to play Germany as Hitler would have been too much for Sid Meier’s sensibilities?

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 9:51 pm

The portrayals of each nationality in Civilization are hilariously cliched and all too American in their view of the world. At the same time, though, they also have much to do with marketing concerns. At the time of Civilization I’s release, Germany was a big market for computer games, but Russia and China were not (yet). A game which you could play as Hitler would get banned in Germany immediately.

Alex Smith

November 20, 2020 at 11:25 pm

In fact, according his autobiography, Sid wrestled with the Hitler issue with the first Civ and was torn between using Hitler, using a different leader, or even just dodging the issue by not including the Germans at all. While he says that it was a combination of the strange moral position it would put the player in and the German legal situation, reading between the lines it seems to me that he would have used Hitler if not for the legal issues.

Matt Wigdahl

November 20, 2020 at 9:07 pm

I suspect one of the reasons the Axis and the Confederacy are more popular “sides” to play in wargames as opposed to the Allies and the Union, respectively, is because they were historically the losers.

It’s far more compelling and satisfying to convert a nation-crushing historical loss to a win than it is to move up the date of your enemy’s historical defeat from May to March. The former flatters you that you’re a better strategist than one of the most infamous figures in history. The latter just means you got the inevitable grind over with a bit more quickly.

John

November 21, 2020 at 2:05 am

I tend to agree. I know that when I play Crusader Kings, for example, one of my favorite things to do is to conquer all of the British isles as the Scots, the Irish, or especially as the Welsh. Anyone but the English. Still, it’s only one of the reasons a game about Nazis or Confederates might be popular.

It’s worth considering the others too, especially when they’re so troubling.

Keith Palmer

November 21, 2020 at 3:02 am

So far as “losers to winners” goes, the coverage of this particular wargame had me wondering all of a sudden if there’s any halfway plausible way to game out “the French and British defeat Germany in 1939-40, or at least avert the fall of France” (even leaving aside the tut-tutting about earlier appeasement and letting the Nazi-Soviet Pact be established). That the thought came to me all of a sudden seems to mean it’s not a popular subject for “alternative history” speculation, anyway.

Avian Overlord

November 22, 2020 at 7:03 pm

There’s a lot of WW2 wargames that let that happen. But it tends not to be focused on for practical reasons. If the French win, then the Soviets and Americans don’t have anything to do, which is a bit boring if you wanted to play as them. So France tends to made weaker than it was historically in order to ensure you get to all the fun stuff like the Battle of Britain, Barbarossa, and D-day.

Niccolò

November 20, 2020 at 7:56 pm

Panzer General was already an anchromism in 1994

I guess that it should read “anachronism”?

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 8:17 pm

Thanks!

Folke

November 20, 2020 at 8:02 pm

I don’t think there’s a moral value in playing or not playing Afrika Korps or a hypothetical Holocaust Tycoon – the virtual Jews don’t exist. There may be reason to suspect the sanity or moral integrity of a person who had access to *only* that, but that’s a different question. Many highly popular games involve spurious crimes and murder for no higher motivation – take GTA, for instance. How immoral can a thing be if it doesn’t seem to hurt the moral sensibilities of the majority of people, and who is to be the judge of that *before* the moral climate has changed?

That said, one would do well to remember that its terribly easy for us to condemn Nazis, having been taught all our lives how evil they are and being surrounded by like-minded people. A German grunt in WWII has no access to Internet to connect to competing values and humanitarians. He has grown up in a world of Nazi indoctrination and has been told that “lesser races” present an existential threat to the German people. Thoughts and actions we would consider virtuous would not be judged so by his peers, but cowardly and traitorous instead. They would get him ostracized at best and killed at worst. Few have the faculties to rise above that, as history shows.

On that vein, I think it would be interesting to have a game that incentivized immoral behaviour. The game would allow moral choices, but would not reward the player for taking them, but punish him instead. It’s easy to be virtuous when there’s no benefit in not doing so.

The scariest thing about Nazis is the “banality of evil” – Nazis were not monsters but humans. Germans had no special qualities that made them special in that regard, no genocide genes or a remarkably xenophobic culture pre-WWI. So the wise thing to do is not to recreate the conditions that have promoted genocides in the past, and not rely on alleged moral superiority as an impervious moral shield against that. Most if not all of history’s genocidal leaders have firmly believed that *they* hold the moral high ground.

Simon_Jester

October 10, 2022 at 7:47 pm

Looking at this later, there are two complications.

First, when we talk about the strategy game- the discussion of the morality of a game like Panzer General doesn’t hinge on judging the players. It hinges on the game itself. Does the game do right by, or wrong by, the memory and the reality of what happened during this era or this war? It’s far too common in this sort of discussion for people to wind up deflecting discussion of the game into “well, this doesn’t make people who play the game into bad people!” And they’re right; it does not. The heart of the discussion is precisely about the effect of the game and how it potentially shapes the thought processes of a person who is not somehow intrinsically bad when they start playing and likely won’t be intrinsically bad when they stop.

Second, when we talk about the historical Nazis- remember that we are not discussing foot soldiers drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1942 after a stint in the Hitler Youth as teenagers. We are discussing generals, administrators, diplomats. Men mostly born before 1900. Men who had grown up in the constitutional monarchy of the Kaiser’s Germany. Men whose first exposure to the concepts of warfare as schoolboys would be history stretching back to Napoleon, with norms of not willfully massacring civilian populations, not indoctrination crafted by Goebbels to turn them into Nazi doom-troopers. Men with educations, in their maturity and their old age, with time to form confident beliefs of their own. Men who had experienced the First World War and the sheer appalling scale of industrialized death and conflict.

These are men who should have known better, by any reasonable standard, than to think that turning a continent and a half into a charnel-house was in any way an acceptable prize to pay for the aggrandizement of the ‘German race.’

Furthermore, these are not men who simply served passively. We are, again, talking about leaders, administrators, generals. Men who were not just following orders, but also giving them, whose explicit job within the Third Reich was to use their full ingenuity and all their waking hours to maximize the extent to which Hitler’s orders and designs could be carried out.

There are sharp limits to how much sympathy I can muster for any of them.

So there is a sharp l

Nate

November 20, 2020 at 8:50 pm

Interesting moral questions. Thanks fir raising them. A bit of a crossover to the Analog Antiquarian side.

Doubled word:

more supplies than than his army

Suggest a comma between:

too deeply too quickly

Suggest word order “fully came”:

code breakers came fully into their own

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 9:44 pm

Thanks!

Sniffnoy

November 20, 2020 at 9:35 pm

I think actual military historians would grimace at the characterization you paint of it here… although that sort of military history certainly does exist. Bret Devereaux discusses this in this recent blog post (have you seen his blog, by the way? It’s quite interesting :) ); apparently real military historians refer to this sort of thing as “drums and trumpets” history. But, y’know, there is such a thing as military history beyond that…

Also, I have to point out that your hypothetical version of Transport Tycoon sort of exists: Brenda Romero’s Train. Of course, there the whole point of the thing is as something of a social experiment, seeing whether players will keep on trying to win according to the rules once they’ve figured out just what it is they’re doing, rather than as an ordinary fun game where of course the designer intends for you to try to win as normal!

(Also, in homophone spotting: “annunciation” should be “enunciation”)

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 10:00 pm

Thanks!

I did use “popular military history” when I first introduced the idea, but that’s a bit of a mouthful to state over and over. ;) (“Military history” is bad enough.) Certainly a *form* of military history dates all the way back to Thucydides. But that’s not really what I mean here.

Markus

November 20, 2020 at 9:48 pm

The question of “how much is too much, how far is too far” of course is one of eternal presence in computer gaming in particular, and of course doesn’t end at the Strategy genre. Is it morally or ethically justifiable for a civilized human being to play a FPS where you pull a virtual trigger to blow a virtual avatar’s virtual head off? How would that question be answered for Simulation games? In Aces of the Deep (Sierra/Dynamix) you take the role of a German U-Boat captain, a field of (real) war that too is historically ripe with questions and various answers of soldiers’ knight-like honor vs. Nazi-fueled moral corruptness. The game makes no mention of enemy casualties, the score there is called “tonnage” and not lives lost even when you sink a large troop carrier with thousands of souls. Is that okay? How about a flight simulator that would put you in the pilot’s seat of the Enola Gay delivering a nuclear bomb to Japan? In B-17 Flying Fortress (Microprose) I take virtual command of an allied bomber and its crew. Me being German, this may lead to missions in the game that have me taking off in England to make a run against my actual real life birthplace and home town, where I live, knowing fully well and in great detail the utter devastation and pure carnage, the eradication of lives and livelihood of the civilian population this town (like so many others) suffered during WW2 at the hands of allied bombers. I can see the scars to this day around here, yet I do play such a game. Is that okay? I’m not going to pretend to have a definitive answer to that problem, but I totally agree that this can cause a rather uneasy feeling during gameplay.

In 1983, there was a German game on the C64 called “Imperator”, a simple management simulation type of game set in ancient Rome, the goal of which was to act as an efficient roman emperor. It didn’t take long until someone hacked this into a Nazi-era game titled “Hitler Diktator”, with the gameplay now involving elements such as efficient deportation and killing of Jews. (Not surprisingly, this hack was and still is very much illegal in Germany.) As kids back then, we probably all knew this stuff was not good at all, still the game saw significant underground circulation. And no doubt some of us did in fact play it, if only for its shock value and it being “crass” that way. And of course because it was verboten.

That said, I cannot let your idea of “the conspirators were not objecting to the Holocaust that was going on all around them” stand without comment, this is patently false. It is true that general resistance to Naziism came from various directions with various motivations, not all of which might look agreeable in retrospect. (History can be funny that way…) Just likewise, it is impossible to look into everyone’s head to know what was truly on their mind. But the fact that pretty much most of the conspirators particularly of the July 20th 1944 assassination plot (which is the context that lead to Rommel’s death), just like other resistance networks before and after, were in fact very much objecting and reacting to the inhumanity of the regime, the murders, the deportations, etc., and took this as one major if not the major motivation for their actions, is historically clear and well documented, through surviving witnesses, through their written communcation with each other, through their documented testimony after being arrested. Yes of course they did see the danger of Germany’s destruction in losing the war and tried to prevent that from happening, but this was not their primary reason for attempting to overthrow the regime by killing Hitler, and especially not their sole reason. To state these people were all cool with the Holocaust is, I’m sorry to say, quite frankly, ridiculously revisionist hogwash.

It is indeed still not known how exactly Rommel was involved in that plot, even though the view of him has significantly shifted away from the post-war glorification by further research and analysis during the more recent years and decades, in Germany no less. Most historians seem to agree that the likeliest scenario is he knew of the plot in some way or another. He had close contact to many of the conspirators, and certainly may have been approached by them in search of support since the Nazi propaganda had made him to be the widely known and iconic “hero of El-Alamein”. Ultimately though, he then obviously chose not to participate, but also chose not to reveal or hinder the plan.

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 10:06 pm

It seems you know more about the assassination plot than I do. I defer to your expertise. I’ve excised the paragraph in question; the article can stand perfectly well without it. Thanks!

Markus

November 21, 2020 at 11:49 am

I don’t know if it’s safe to say I’d know more about it, this isn’t my field of expertise. Though I’ve certainly been subjected to modern German education on the matter as well as to a barrage of German documentaries, which may be somewhat more detailed and diverse than the non-german simplifications that tend to run on the likes of Histery Channel et al. Just as much as there’s a difference in, say, German movies about it versus the general Hollywood fare, which is also something that’s easily lost on people especially when they don’t speak the language (understandably). Beyond the understanding that the Nazis were evil, history in general and WW2 history in particular has the nasty habit of becoming rather complex underneath the surface the more and the longer you look at it.

It’s easy to paint an overly simplified picture of anyone within the resistance, like I said their backgrounds and motivations did differ significantly. This was evident to them as well – even when different networks knew of each other and cooperated, there were points when beyond their mutual agreement that a revolt or assassination was necessary they couldn’t necessarily agree on where to go from there in case they’d succeed. With members of the resistance from within the armed forces, it’s important to keep in mind that as officers they usually came from a very conservative, old aristocracy (remember, nobility has been officially abolished in Germany since 1919, much unlike other parts of the world), predominantly nationalistic walks of life, educated in the interwar political climate after losing WW1 or being WW1 veterans themselves, many of them originally being early Nazi supporters who initially didn’t really see anything wrong with Hitler and his ideas, instead supporting how he was “making Germany great again” so to speak (…cough…). Even granting them the benefit of not knowing history as it has unfolded to us up to now, that’s an issue. They weren’t the knights in shining armor leading a virtuous and rightous life from birth to death that they’re sometimes made out to be. They had a tendency to feel bound to their oath to Hitler with a quite Prussian sense of duty and honor (which of course was the reason why Hitler had this pledge of allegiance made to and about him personally, instead of “country” or “peoples” or “constitution” or whatever), and many of them initially were complicit in carrying out Nazi policy during the war. Even someone as glorified as Stauffenberg was known to express ideas that aren’t pleasant to consider nowadays, such as his belief that there’d be a natural order or inequality for humans, a caste system, a hierarchy (like I said, old nobility); an idea which of course the Nazis embraced in their classification of “subhumans”. But they also usually were brought up as devout Christians, and for many this was something they couldn’t disregard in light of the inhumane Nazi ideology and what that meant in practice. What we now refer to as “crimes against humanity”, which wasn’t quite a term yet back then, usually was the one unifying factor that made most of them realize that it’s necessary to stand up and oppose this evil. And quite a few of them, such as e.g. Henning von Tresckow, were known to express their belief that even if they should fail (and often they did consider their chances of success to be slim), they would still have to make this big statement of opposition to Hitler and to what the Nazis did and stood for, as a mark in history and as a message to the world. And they knew going in they’d possibly be sacrificing their lives in the process.

Back to a game like Panzer General, one aspect to consider is that its year of release is a time when there still were remnants abound of the prevailing myth of a partly “clean war” and a general lack of complicity of regular army (Wehrmacht) as opposed to the ruthless inhumanity of SS or Einsatzgruppen, thanks in no small part due to some old veterans and their tendency to deny guilt and claiming ignorance and “only following orders”, trying to whitewash their legacy in the process (while many others of course did admit guilt and fully came clean about what they saw or participated in). The decades since 1994 have mostly seen this myth getting wiped away (certainly in Germany), partly due to those old veterans slowly but surely dying out, partly due to continuous historical research still uncovering details and secrets previously condidered lost in time. Nowadays it is clear that there was widespread and coordinated cooperation and participation between Wehrmacht/SS/Police/Einsatzgruppen. While Wehrmacht units certainly were primarily tasked with “classic” warfare, advancing and defending the frontline, they were not detached from the big picture genocidal implications and actions against the civilian population and elite/politicians/officials in the hinterland, frequently being hands-on complicit in murders and deportations. The average “grunt in the trenches” may have for some time managed to remain ignorant to all that, but you could not serve as an officer on the Eastern Front without knowing what’s going on and playing your part in it. That was the reason why you were there after all. The war especially in the east was driven first and foremost by Nazi ideology of supremacy and genocide. And yeah, you’re right, it’s probably worthwhile to keep this in mind when playing a Strategy game like this, or any game in such a context.

Buck

November 20, 2020 at 11:01 pm

Aces of the Deep has a note after installation (because noone reads manuals I guess) that mentions the crimes of the Nazis, which I found notable because I haven’t seen that in any other war game so far in which you could play as Nazi Germany, including Aces over Europe. Also, the sound of sinking ships while you’re under water is very eerie…

Jimmy Maher

November 21, 2020 at 8:57 am

That’s great. As I mentioned, a note of that sort somewhere in the Panzer General manual — at least acknowledging the Holocaust amidst all the drums and trumpets — would have gone a long way to make me feel better about the game.

I think back to the first Lord of the Rings game by Interplay. There was a thoughtful footnote in that manual, saying that the traditional depiction of wolves as evil killers was not grounded in reality, and explaining more generally that the world has progressed since Tolkien wrote his novels and that his attitudes toward many subjects should be taken with a grain of salt. I’ve often wondered who at Interplay was responsible for inserting that; we don’t tend to see a lot of this sort of nuance in the games of 1980s and 1990s.

Klaus

November 20, 2020 at 10:02 pm

“Before you rush to answer, ask yourself how you would feel about, say, a version of Transport Tycoon where you have to move Jews from the cities where they live to the concentration camps where they will die.”

Are you aware of Brenda Romero’s boardgame, Train?

Jimmy Maher

November 20, 2020 at 10:07 pm

Yes. Was just being a bit cagey. ;)

Kai

November 20, 2020 at 10:52 pm

Great article. Personally I’m torn about the subject. I guess there are moral lines somewhere that games should not cross, but I would not think Panzer General anywhere near those.

OTOH I am generally baffled by how many games make war or violence their primary focus. As if anything short of digital mass murder is way too boring. One of my favorite genres, the RPG, is hardly an exception to that. And it’s not that I am feeling remorse after slaughtering NPCs for dubious claims of wrongdoing — they are a bunch of pixels after all — but it gets me thinking how these games are often more geared towards destruction than creation, and how they are lacking in nuance and all too quickly resorts to terminal measures in order to resolve conflict.

But even more abstract games give me pause at times, like using nuclear weapons in a match of Civilization. If you really think about the implications, then this should simply be a no go. But from a purely tactical consideration within the game, it may be absolutely the right thing to do.

Where I usually draw the line is when it comes to assuming the role of malevolent or criminal characters. While this can mean a sizable disadvantage in plenty of RPGs, stealing or being nasty for being nasty’s sake is something I would not stoop to in real life, and neither will I within a game.

But lobbing nukes at enemies or mowing down scores of faceless people seems so far fetched from reality that it somehow becomes an acceptable (if perhaps questionable) behavior. So why shouldn’t somebody enjoy a game of Panzer General, too? If it gets them thinking about real world history, I’d consider that a bonus.

Peter Olausson

November 20, 2020 at 11:10 pm

Thanks for a good article. Looking forward to the next.