Writing about Ultima earlier, I described that game as the first to really feel like a CRPG as we would come to know the genre over the course of the rest of the 1980s. Yet now I find myself wanting to say the same thing about Wizardry, which was released just a few months after Ultima. That’s because these two games stand as the archetypes for two broad approaches to the CRPG that would mark the genre over the next decade and, arguably, even right up to the present. The Ultima approach emphasizes the fictional context: exploration, discovery, setting, and, eventually, story. Combat, although never far from center stage, is relatively deemphasized, at least in comparison with the Wizardry approach, which focuses on the process of adventuring above all else. Like their forefather, Wizardry-inspired games often take place in a single dungeon, seldom feature more than the stub of a story, and largely replace the charms of exploration, discovery, and setting with those of tactics and strategy. The Ultima strand is often mechanically a bit loose — or more than a bit, if we take Ultima itself, with its hit points as a purchasable commodity and its concept of character level as a function of time served, as an example. The Wizardry strand is largely about its mechanics, so it had better get them right. (As I wrote in my last post about Wizardry, Richard Garriott refined and balanced Ultima by playing it a bit himself and soliciting the opinions of a few buddies; Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead put Wizardry through rigorous balancing and playtesting that consumed almost a year.) These bifurcated approaches parallel the dueling approaches to tabletop Dungeons and Dragons, as either a system for interactive storytelling enjoyed by “artful thespians” or a single-unit tactical wargame.

Wizardry, then, isn’t much concerned with niceties of setting or story. The manual, unusually lengthy and professional as it is, says nothing about where we are or just why we choose to spend our time delving deeper and deeper into the game’s 10-level dungeon. If a dungeon exists in a fantasy world, it must be delved, right? That’s simply a matter of faith. Only when we reach the 4th level of the dungeon do we learn the real purpose of it all, when we fight our way through a gauntlet of monsters to enter a special room.

CONGRATULATIONS, MY LOYAL AND WORTHY SUBJECTS. TODAY YOU HAVE SERVED ME WELL AND TRULY PROVEN YOURSELF WORTHY OF THE QUEST YOU ARE NOW TO UNDERTAKE. SEVERAL YEARS AGO, AN AMULET WAS STOLEN FROM THE TREASURY BY AN EVIL WIZARD WHO IS PURPORTED TO BE IN THE DUNGEON IMMEDIATELY BELOW WHERE YOU NOW STAND. THIS AMULET HAS POWERS WHICH WE ARE NOW IN DIRE NEED OF. IT IS YOUR QUEST TO FIND THIS AMULET AND RETRIEVE IT FROM THIS WIZARD. IN RECOGNITION OF YOUR GREAT DEEDS TODAY, I WILL GIVE YOU A BLUE RIBBON, WHICH MAY BE USED TO ACCESS THE LEVEL TRANSPORTER [otherwise known as an “elevator”] ON THIS FLOOR. WITHOUT IT, THE PARTY WOULD BE UNABLE TO ENTER THE ROOM IN WHICH IT LIES. GO NOW, AND GOD SPEED IN YOUR QUEST!

And that’s the last we hear about that, until we make it to the 10th dungeon level and the climax.

What Wizardry lacks in fictional context, it makes up for in mechanical depth. Nothing that predates it on microcomputers offers a shadow of its complexity. Like Ultima, Wizardry features the standard, archetypical D&D attributes, races, and classes, renamed a bit here and there for protection from Mr. Gygax’s legal team. Wizardry, however, lets us build a proper adventuring party with up to six members in lieu of the single adventurer of Ultima, with all the added tactical possibilities managing a team of adventurers implies. Also on offer here are four special classes in addition to the basic four, to which we can change characters when they become skilled enough at their basic professions. (In other words, Wizardry is already offering what the kids today call “prestige classes.”) Most impressive of all is the aspect that gave Wizardry its name: priests eventually have 29 separate spells to call upon, mages 21, each divided into 7 spell levels to be learned slowly as the character advances. Ultima‘s handful of purchasable scrolls, which had previously marked the state of the art in CRPG magic systems, pales in comparison. Most of the depth of Wizardry arises one way or another from its magic system. It’s not just a matter of learning which spells are most effective against which monsters, but also of husbanding one’s magic resources: deciding when one’s spell casters are depleted enough that it’s time to leave the dungeon, deciding whether the powerful spell is good enough against that demon or whether it’s time to use the really powerful one, etc. It’s been said that a good game is one that confronts players with interesting, non-obvious — read, difficult — decisions. By that metric, magic is largely what makes Wizardry a good game.

Of course, Wizardry‘s mechanics, from its selection of classes and races to its attribute scores that max out at 18 to its armor-class score that starts at 10 and moves downward for no apparent reason, are steeped in D&D. There’s even a suggestion in the manual that one could play Wizardry with one’s D&D group, with each player controlling a single character — not that that sounds very compelling or practical. The game also tries, not very successfully, to shoehorn in D&D‘s mechanic of alignment, a silly concept even on the tabletop. On the computer, good, evil, and neutral are just a set of arbitrary restrictions: good and evil cannot be in the same party, thieves cannot be good.

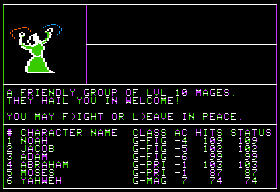

Sometimes you meet “friendly” monsters in the dungeon. If good characters kill them anyway, or evil characters let them go, there’s a chance that their alignments will change — which can in turn play the obvious havoc with party composition. (In an amusing example of unintended emergent behavior, it’s also possible for the “evil” mage at the end of the game to be… friendly. Now doesn’t that present a dilemma for a “good” adventurer, particularly since not killing him means not getting the amulet that the party needs to get out of his lair.)

So, Greenberg and Woodhead were to some extent just porting an experience that had already proven compelling as hell to many players to the computer, albeit doing a much more complete job of it than anyone had managed before. But there’s also much that’s original here. Indeed, so much that would become standard in later CRPGs has its origin here that it’s hard to know where to begin to describe it all. Wizardry is almost comparable to Adventure in defining a whole mode of play that would persist for many years and countless games. For those few of you who haven’t played an early Wizardry game, or one of its spiritual successors (read: slavish imitators) like The Bard’s Tale or Might and Magic, I’ll take you on a very brief guided tour of a few highlights. Sorry about my blasphemous adventurer names; I’ve been reading the Old Testament lately, and it seems I got somewhat carried away with it all.

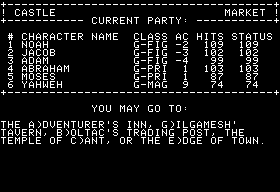

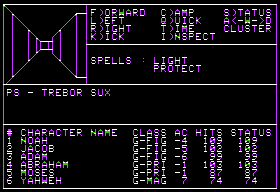

Wizardry is divided into two sections: the castle (shown below), where we do all of the housekeeping chores like making characters, leveling up, putting together our party, shopping for equipment, etc.; and the dungeon, where the meat of the game takes place.

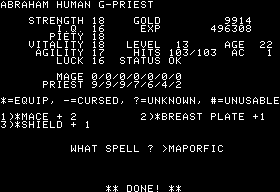

When we enter the dungeon, we start in “camp.” We are free to camp again at any time in the dungeon, as long as we aren’t in the middle of a fight. Camping gives us an opportunity to tinker with our characters and the party as a whole without needing to worry about monsters. We can also cast spells. Here I’ve just cast MAPORFIC, a very useful spell which reduces the armor class of the entire party by two for the duration of our stay in the dungeon. All spells have similar made-up names; casting one requires looking it up in the manual and entering its name.

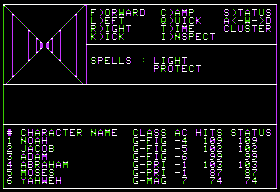

Once we leave camp, we’re greeted with the standard traveling view: a first-person wireframe-3D view of our surroundings occupies the top left, with the rest of the screen given over to various textual status information and a command menu that’s really rather wasteful of screen space. (I suspect Greenberg and Woodhead use it because it gives them something with which to fill up some space that they don’t have to spend computing resources dynamically updating.)

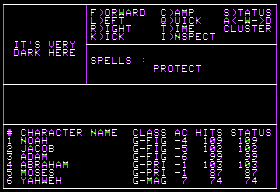

I was just saying that Wizardry manages to be its own thing, separate from D&D. That becomes clear when we consider the player’s biggest challenge: mapping. It’s absolutely essential that she keep a meticulous map of her explorations. Getting lost and not knowing how to return to the stairs or elevator is almost invariably fatal. While tabletop D&D players are often also expected to keep rough maps of their journeys, few dungeon masters are as unforgiving as Wizardry. In addition to all the challenges of keeping track of lots of samey-looking corridors and rooms, the game soon begins to throw other mapping challenges at the player: teleporters that suddenly throw the party somewhere else entirely; spinners that spin them in place so quickly it’s easy to not realize it’s happened; passages that wrap around from one side of the dungeon to the other; dark areas that force one to map by trial and error, literally by bashing one’s head against the walls.

On the player’s side are an essential mage spell, DUMAPIC, that tells her exactly where she is in relation to the bottom-left corner of the dungeon level; and the knowledge that all dungeon levels are exactly 20 spaces by 20 spaces in size. Mapping is such a key part of Wizardry that Sir-tech even provided a special pad of graph paper for the purpose in the box, sized 20 X 20.

The necessity to map for yourself is easily the most immediately off-putting aspect of a game like Wizardry for a modern player. While games before Wizardry certainly had dungeons, it was the first to really require such methodical mapping. The dungeons in Akalabeth and Ultima, for instance, don’t contain anything other than randomized monsters to fight with randomized treasure. The general approach in those games becomes to use “Ladder Down” spells to quickly move down to a level with monsters of about the right strength for one’s character, to wander around at random fighting monsters until satisfied and/or exhausted, then to use “Ladder Up” spells to make an escape. There’s nothing unique to really be found down there. Wizardry changed all that; its dungeon levels may be 99% empty rooms, corridors, and randomized monster encounters, but there’s just enough unique content to make exploring and mapping every nook and cranny feel essential. If that’s not motivation enough, there’s also the lack of a magic equivalent to “Ladder Up” and “Ladder Down” until one’s mage has reached level 13 or higher. Map-making is essential to survival in Wizardry, and for many years to follow laborious map-making would be a standard part of the CRPG experience. It’s an odd thing: I have little patience for mazes in text adventures, yet find something almost soothing about slowly building up a picture of a Wizardry dungeon on graph paper. Your milage, inevitably, will vary.

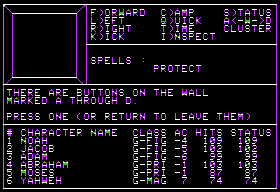

In general Wizardry is all too happy to kill you, but it does offer some kindnesses here and there in addition to DUMAPIC and dungeon levels guaranteed to be 20 X 20 spaces. These proving grounds are, for example, one of the few fantasy dungeons to be equipped with a system of elevators. They let us bypass most of the levels to quickly get to the one we want. Here we’re about to go from level 1 to level 4.

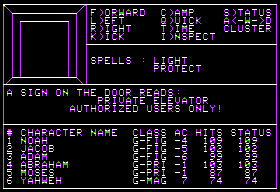

From level 4 we can take another elevator all the way down to level 9. But, as you can see below, entering that second elevator is allowed for “authorized users only.”

Wizardry doesn’t have the ability to save any real world state at all. Only characters can be saved, and only from the castle. Each dungeon level is reset entirely the moment we enter it again (or, more accurately, reset when we leave it, when it gets dumped from memory to be replaced by whatever comes next). Amongst other things, this makes it possible to kill Werdna, the evil mage of level 10, and thus “win the game” over and over again. One way the game does manage to work around this state of affairs is through checks like what you see illustrated above. We can only enter the second elevator if we have the blue ribbon — and we can only get that through the fellow who enlisted our services in another part of level 4 (see the quotation above). By tying progress through the plot (such as it is) to objects in this way, Greenberg and Woodhead manage to preserve at least a semblance of game state. The blue ribbon is of course an object which we carry around with us, and that is preserved when we save our characters back at the castle. Therefore it gives the game a way of “knowing” whether we’ve completed the first stage of our quest, and thus whether it should allow us into the lower levels. It’s quite clever in its way, and, again, would become standard operating procedure in many other RPGs for years to come. The mimesis breaker is that, just as we can kill Werdna over and over, we can also acquire an infinite number of these blue ribbons by reentering that special room on level 4 again and again.

There’s a surprising amount of unique content in the first 4 levels: not only our quest-giver and the restricted elevator, but also some special rooms with their own atmospheric descriptions and a few other lock-and-key-style puzzles similar to, although less critical than, the second-elevator puzzle. In levels 5 through 9, however, such content is entirely absent. These levels hold nothing but empty corridors and rooms. I believe the reason for this is down to disk capacity. Wizardry shipped on two disks, but the first serves only to host the opening animation and some utilities. The game proper lives entirely on a second disk, as must all of the characters that players create. This disk is stuffed right to the gills, and probably would not allow for any more text or “special” areas. Presumably Greenberg and Woodhead realized this the hard way, when the first four levels were already built with quite a bit of unique detail.

We start to see more unique content again only on level 10, the lair of Werdna himself. There’s this, for instance:

From context we can conclude that Trebor must be the quest giver that we met back on level 4. “Werdna” and “Trebor” are also, of course, “Andrew” and “Robert” spelled backward. Wizardry might like to describe itself using some pretty high-minded rhetoric sometimes and might sport a very serious-looking dragon on its box cover, but Greenberg and Woodhead weren’t above indulging in some silly fun in the game proper. When mapped, level 8 spells out Woodhead’s initials; ditto level 9 for Greenberg’s.

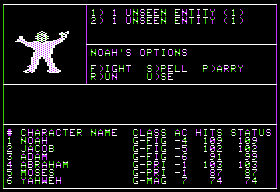

In the midst of all this exploration and mapping we’re fighting a steady stream of monsters. Some of these fights are trivial, but others are less so, particularly as our characters advance in level and learn more magic and the monsters we face also get more diverse and much more dangerous, with more special capabilities of their own.

The screenshot above illustrates a pretty typical combat dilemma. In an extra little touch of cruelty most of its successors would abandon, Wizardry often decides not to immediately tell us just what kind of monsters we’re facing. The “unseen entities” above could be Murphy’s ghosts, which are pretty much harmless, or nightstalkers, a downright sadistic addition that drains a level every time it successfully hits a character. (Exceeded in cruelty only by the vampire, which drains two levels.) So, we are left wondering whether we need to throw every piece of high-level magic we have at these things in the hopes of killing them before they can make an attack, or whether we can take it easy and preserve our precious spells. As frustrating as it can be to waste one’s best spells, it usually pays to err on the side of caution in these situations; once to level 9 or so, each experience level represents hours of grinding. Indeed, if there’s anything Wizardry in general teaches, it’s the value of caution.

I won’t belabor the details of play any more here, but rather point you to the CRPG Addict’s posts on Wizardry for an entertaining description of the experience. Do note as you read that, however, that he’s playing a somewhat later MS-DOS port of the Apple II original.

The Wizardry series today has the reputation of being the cruelest of all of the earlier CRPGs. That’s by no means unearned, but I’d still like to offer something of a defense of the Wizardry approach. In Dungeons and Desktops, Matt Barton states that “CRPGs teach players how to be good risk-takers and decision-makers, managers and leaders,” on the way to making the, shall we say, bold claim that CRPGs are “possibly the best learning tool ever designed.” I’m not going to touch the latter claim, but there is something to his earlier statements, at least in the context of an old-school game of Wizardry.

For all its legendary difficulty, Wizardry requires no deductive or inductive brilliance or leaps of logical (or illogical) reasoning. It rewards patience, a willingness to experiment and learn from mistakes, attention to detail, and a dedication to doing things the right way. It does you no favors, but simply lays out its world before you and lets you sink or swim as you will. Once you have a feel for the game and understand what it demands from you, it’s usually only in the moment that you get sloppy, the moment you start to take shortcuts, that you die. And dying here has consequences; it’s not possible to save inside the dungeon, and if your party is killed they are dead, immediately. Do-overs exist only in the sense that you may be able to build up another party and send it down to retrieve the bodies for resurrection. This approach is probably down at least as much to the technical restrictions Greenberg and Woodhead were dealing with — saving the state of a whole dungeon is complicated — as to a deliberate design choice, but once enshrined it became one of Wizardry‘s calling cards.

Now, this is very possibly not the sort of game you want to play. (Feel free to insert your “I play games to have fun, not to…” statements here.) Unlike some “hardcore” chest-thumpers you’ll meet elsewhere on the Internet, I don’t think that makes you any stupider, more immature, or less manly than me. Hell, often I don’t want to play this sort of game either. But, you know, sometimes I do.

My wife and I played through one of the critical darlings of last year, L.A. Noire, recently. We were generally pretty disappointed with the experience. Leaving aside the sub-Law and Order plotting, the typically dodgy videogame writing, and the most uninteresting and unlikable hero I’ve seen in a long time, our prime source of frustration was that there was just no way to fuck this up. The player is reduced to stepping through endless series of rote tasks on the way to the next cut scene. The story is hard-coded as a series of death-defying cliffhangers, everything always happening at the last possible second in the most (melo-)dramatic way possible, and the game is quite happy to throw out everything you as the player have, you know, actually done to make sure it plays out that way. In the end, we were left feeling like bit players in someone else’s movie. Which might not have been too terrible, except it wasn’t even a very good movie.

In Wizardry, though, if you stagger out of the dungeon with two characters left alive with less than 10 hit points each, that experience is yours. It wasn’t scripted by a hack videogame writer; you own it. And if you slowly and methodically build up an ace party of characters, then take them down and stomp all over Werdna without any problems at all, there’s no need to bemoan the anticlimax. The satisfaction of a job well and thoroughly done is a reward of its own. After all, that’s pretty much how the good guys won World War II. To return to Barton’s thesis, it’s also the way you make a good life for yourself here in the real world; the people constantly scrambling out of metaphorical dungeons in the nick of time are usually not the happy and successful ones. If you’re in the right frame of mind, Wizardry, with its wire-frame graphics and its 10 K or so of total text, can feel more immersive and compelling than L.A. Noire, with all its polygons and voice actors, because Wizardry steps back and lets you make your own way through its world. (It also, of course, lets you fuck it up. Oh, boy, does it let you fuck it up.)

That’s one way to look at it. But then sometimes you’re surprised by six arch-mages and three dragons who proceed to blast you with spells that destroy your whole 15th-level party before anyone has a chance to do a thing in response, and you wish someone had at least thought to make sure that sort of thing couldn’t happen. Ah, well, sometimes life is like that too. Wizardry, like reality, can be a cruel mistress.

I’m making the Apple II version and its manual available for you to download, in case you’d like to live (or relive) the experience for yourself. You’ll need to remove write permissions from the first disk image before you boot with it. As part of its copy protection, Wizardry checks to see if the disk is write protected, and refuses to start if not. (If you’re using an un-write-protected disk, it assumes you must be a nasty pirate.)

Next time I’ll finish up with Wizardry by looking at what Softline magazine called the “Wizardry phenomenon” that followed its release.

David Rugge

March 23, 2012 at 7:11 pm

I’m curious: did you play through the game with a hacked party (via Wizfix or hex-editing) or were you actually able to build up the pictured characters from scratch? I remember that it took me over a year to finish Wizardry as a pre-teen in the mid 80’s, and that was greatly aided by my “ID item 9” party of cheat characters who mapped the dungeon out for my non-cheating party, rescued then when they died, etc.

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2012 at 8:18 pm

We didn’t use any character editors, but we did cheat a little bit. We rerolled our characters until we got really good ability scores, which is arguably against the spirit of the game. Then we did the old trick of rolling up a bunch of dummy characters and pooling their gold to the one we actually cared about. This let us start everyone off with the best (non-magical) equipment their class allowed. And we allowed ourselves to save state on the emulator every time we returned to the castle. That way if we got killed in the dungeon we could just restore to that point. I justified this to myself with the reasoning that an actual Apple II player COULD effectively do the same thing, if she were willing to take the time to backup her scenario disk through the utility menu after every expedition. My wife, who’s much less patient than I with these old games (probably because she didn’t grow up with them like I did), wanted to start saving after every encounter by the time we got to the bottom level, but I was strong enough to say no to that. I did, however, eventually let us start reloading when we got level-drained, the thing which I think might be the most unspeakably cruel element of the whole game.

Even with all that, it still took us a good couple of weeks of playing, and quite some total party kills, to finish.

Nathanael

March 6, 2021 at 1:56 am

For reference, the original players on both the Apple II and the IBM PC needed a special low-level disk copier program to backup the scenario disk (!!!) because of the highly unusual way the Wizardry disks were recorded.

However, lots and lots of people had such copier programs, and I absolutely played by making a copy before exploring any new area or difficult part.

Joshua Buergel

March 23, 2012 at 10:30 pm

I never played the Apple II version of this game, instead playing the MS-DOS port of the game on my PC Jr, but this was the game that turned me into a life-long computer gamer. I had certainly played on the Apples at school (notably playing a lot of Oregon Trail and Odyssey (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odyssey:_The_Compleat_Apventure)), but this was the game that got me hooked. Being a 9 year old with nothing better to do, I did manage to win the game sans cheats.

Of course, upon replying, I stumbled upon a cheat which turned into a source of great amusement. As I recall, you swapped in a different disk at some point during the character saving process on the MS-DOS version. Maybe you saved characters to a separate, specially formatted disk? At any rate, one day, I absent-mindedly stuck in a regular, unformatted disk instead of the correct one during this process, and to my surprise, the game didn’t fall over. Instead, it lost track of whether I had spent my experience or not, allowing me to infinitely level up my characters. Well then! Let me tell you, I had one heck of a powerful character going there, right up until he died of old age in his sleep. Easily my favorite computer game death of all time, right up until the time I was killed by the ball and chain attached to my ankle, which fell on my head after I fell down a pit in Nethack.

Br. Bill

January 10, 2018 at 6:27 am

My college roommate and I stumbled into the MS-DOS version’s great savior. If you pulled the save disk while you were in the dungeon, when you came back to the game later, the party was just in the dungeon waiting for you to go rescue them.

Furthermore, it didn’t save the results of your melee until it was over (either you killed them, they killed you, or you ran away). So if you stumbled into a group of Archmages before you could handle that, and all your party got killed, if you were quick enough to flip up the disk lock and pull the disk before it saved, you could go fetch everyone, and they’d be uninjured.

But yeah, it’s a cheat.

Sslaxx

April 3, 2012 at 12:08 am

Ah, good times. I remember playing Wizardry 1 on an Apple IIc back at school. Should get round to re-installing Wizardry 8 sometime.

Laroquod

April 13, 2012 at 8:02 pm

“And dying here has consequences; it’s not possible to save inside the dungeon, and if your party is killed they are dead, immediately. Do-overs exist only in the sense that you may be able to build up another party and send it down to retrieve the bodies for resurrection.”

The above quote is only technically true in that those were the rules of the game. Nobody followed those rules, however. Back in the day, every player of Wizardry knew that if your party died, all you had to do was open the disk drive before pressing a key to move on, and your party’s death would not be saved to disk. We all knew these ‘secret’ tips and shared them widely. It was common knowledge and only an idiot would spend hours getting back to where they were, when they could just press RESET at the correct tim. Anyway, don’t let anyone try to convince you that we all made brand new parties every time we died back in the old hardcore days of CRPG, because for the same reason DRM doesn’t work, nobody could prevent you from having a backup of your save.

Infinite restorability of saves has always been the rule in story games, whether the designers wanted it that way or not. In many cases, like Wizardry, the unrestrainability of technology saved the game designers from their own folly.

In an emulator, you can probably replicate the same effect by force-quitting instead of pressing a key after death.

Jimmy Maher

April 14, 2012 at 9:29 am

That tricked worked in Castle Wolfenstein, but Wizardry actually made things more complicated. When the party enters the dungeon, it marks each character as being away on expedition, and marks them as returned only when the party successfully exits. If you just pull the disk out of the drive after losing a fight, your characters are left in a sort of limbo, inaccessible. Third-party utilities could be used to recover them, of course; as mentioned in the post, cheating at Wizardry became something of a cottage industry for a while.

Like with many early games, especially The Prisoner, there’s a metagaming aspect to Wizardry, a sense that success is as much dependent on figuring out how it works as a technical system as working within the ostensible framework of the game itself. (Many early text adventures also share this trait; the player could always go BASIC source diving if she couldn’t figure out some ridiculous puzzle or verb.) A careful player, for example, will note that the “Backup” option from the utilities menu actually gives her a way to preserve her characters between dungeon crawls. This alone makes the game worlds easier, and it’s remarkable how many players still seem to miss it altogether.

Finally, yes, a slightly condescending, pedantic attitude about the way you “should” play is Wizardry’s least appealing personality trait, one that would unfortunately come more and more to the fore as the series continued. Thankfully most modern games put a bit more faith in the player to decide what is hardcore enough for herself.

Laroquod

April 14, 2012 at 4:34 pm

You make good points. I knew about the backup function — but also, of course, it was possible to backup your scenario disk using copydisk or any of the standard disk copy utilities that eveyone knew about (although the boot disk had copy protection on it, you didn’t need to copy that to copy your characters). I failed to recall about the limbo effect but you reminded me about it. But I feel it’s important to understand the way people really did play this game, whether through save backups or via cheats, so that canards about what is the nature of the classic ‘hardcore’ variation on fun won’t be perpetuated. Nobody likes having to redo tons of stuff they did before; that was not any different back then. Anyone who took Wizardry’s strictures seriously and didn’t find the ways around them, probably didn’t play for very long! 8)

P Smith

October 19, 2014 at 12:30 pm

That was a fun read.

I’m sure you’ve heard the stories about DOOM in 1994. Many workplaces had to ban it because of declining productivity in the office.

Been there, done that. That was old news by that time.

My high school had to ban Wizardry back in 1983-84 because so many students were playing Wizardry, among other games. Students booking in to do computer science homework were losing out to obsessed gaming. I was lucky to have an Apple II at home by 1984. Ah, memories.

The Wizardry versus Ultima debate is a lot like the Apple II versus Commodore 64 debate of the same time. Both were great and could be appreciated in their own way, and both changed everything that came after. One didn’t need to be declared “better” unless you’re American (the “only winning matters, no ties allowed” mentality). Wizardry’s minutiae changed gaming, as did Ultima’s “sandbox” world, and everyone’s gaming experience is better for having both. Too bad it took many more years for multiple saved games to become the norm.

And no, it was not “cheating” to repeatedly reroll characters until you got 26-29 points that you could add, that was strategy. It was no more cheating than “roll 4d6, pick the best three” in creating D&D characters.

Freddo

March 12, 2015 at 3:20 pm

But the apple emulator demands “make scenario disk” by inserting a formatted disk into the emulator.

How do I do this?

Can someone tell me? dslspeak@gmail.com

Jimmy Maher

March 13, 2015 at 7:44 am

If your emulator of choice won’t create disk images for you, you can make them using Cider Press in Windows: http://a2ciderpress.com/. I’m sure there are similar utilities for other platforms, but don’t know offhand what they are.

Andrew

October 5, 2015 at 10:34 am

There is a typo in the post. You use ‘Whitehead’ instead of Woodhead: “…but Greenberg and Whitehead weren’t above indulging in some silly fun in the game proper”

There is no need to keep this comment after you’ve fixed it.

Jimmy Maher

October 5, 2015 at 1:37 pm

Thanks!

Pedro Timóteo

March 23, 2016 at 5:41 pm

Me and my habit of re-reading articles… :) A typo:

let’s should be lets, in that context.

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2016 at 7:21 am

Glad you did. :) Thanks!

Spike

January 23, 2018 at 11:10 pm

This was a great read and really took me back.

Another aspect of Wizardry that I remember was that the manual never told you what the required attributes were for the prestige classes. Combine that with the fact that when you leveled up it was possible for some of your attributes to decrease (!), and I never did figure out what you needed in order to have a Lord or Ninja. It wasn’t until I got Wizardry V years later that I found out what the requirements were.

I also remember acquiring a Diadem of Malor in one of the lowest levels. I was so excited that I had such a powerful magic item – until I used it once, at which point it disappeared. There was no indication that this was a one-use item!

Nathanael

March 6, 2021 at 1:58 am

The original manual did tell you the required stats; you probably got a later rerelease.

Marv Chomer

March 9, 2020 at 7:10 pm

This article (and a lot of your other ones that I have read) brought back a ton of memories. We played Wizardry in school in the early 80s on our Apple ][s and (as D&D players) had a blast. We had two different groups of us playing on separate computers. I remember the other group found a powerful item called “winter mittens” or something like that and somehow my friend moved his character to their disk, traded himself the item and then moved his character back to our disk. I wish I could remember the process but they never knew what hit them when they were trying to find their mittens.

Nevertheless, I am really enjoying your blog. I actually found your book on Amazon last week when I was checking out Amiga stuff and found this blog in a non-related way by looking up articles about Archon.

Nathanael

March 6, 2021 at 2:00 am

Oh yeah, the game had a character transfer option to move characters between disks. You could combine this with the ability to make backup disks to “clone” a character with really good stats.

I seem to remember making a party by taking one character who had rolled up super-good states, cloning and renaming the character until I had six copies of them, and then changing their classes to make a party. Start off strong…

Rudy

April 9, 2023 at 10:25 pm

We did this to multiply our resources, specifically the Diadem of Malor. Once we found it we would exit the dungeon, do a clone, go back in, trade the goodies to a player, make his clone and repeat until we had 64 Diadems. When things got dicey, we would just Malor out, regroup and go back in. Since we could never die, the game got boring, so we moved on to Lode Runner.

Von

June 21, 2021 at 2:16 pm

I got this game in the early 80’s, I was around 12 years old. A couple years later i’d use my trusty graph paper to map out and complete the Bard’s tale.

Wizardry is legendary in my mind because I couldn’t get past the first level. I can remember grinding away in the first two rooms, but after that I always died! Hahaha, so cruel, and I guess I didn’t have much patience either. I can vaguely remember starting to copy character disks (of course we all had pirating software) but it all seemed like too much of a chore, and I guess I wasn’t tuned in enough to the apple 2 scene at the time to be encouraged with other cheats. Shame because looking back I definitely agree that hacking was definitely fair game in terms of strategy. I remember amazing my friends when I figured out by trial and error how I could soft-reset the computer in the middle of a castle wolfenstein game, and then if you entered the right “call” code it would jump to the part in memory where you’re escaping the castle! Pretty rudimentary stuff for a developer, but we were just kids hacking around at the time so it was like magic to us.

P.s. thanks for this article. I was thinking about going back and playing wizardry I and using save game states, but after reading your commentary I might skip it and go for something with more puzzles and lore as those are the more enjoyable parts for my play style. Obviously I don’t have the patience required to be a hard-core gamer :> and fall more on the Ultima side of the coin.

Jeff Nyman

September 30, 2021 at 10:31 pm

For all its legendary difficulty, Wizardry requires no deductive or inductive brilliance or leaps of logical (or illogical) reasoning. It rewards patience, a willingness to experiment and learn from mistakes, attention to detail, and a dedication to doing things the right way. It does you no favors, but simply lays out its world before you and lets you sink or swim as you will. Once you have a feel for the game and understand what it demands from you, it’s usually only in the moment that you get sloppy, the moment you start to take shortcuts, that you die.

An interesting parallel here, of course, is Dark Souls. This is a game that came out in 2011 and yet anyone who has played that game would immediately be able to apply the above quote to it.

Which is quite interesting when you consider the temporal duration between these games and the fact that they’re not quite the same genre, perhaps. And yet at the core level of experience, that above quote exemplifies both of them exactly.

What was interesting about Dark Souls is that it really rewarded you for NOT playing it like you probably played most other games. To wit, don’t just run in hack-and-slashing. Because if you do, even the weakest monster in the game might mop up the floor with you. Instead you had to unlearn certain habits of play. And when you did so, the game rewarded you a rich experience.

Maybe that wasn’t at all the intent of Wizardry since you could argue even some of the early precursors, like “pedit5” and “dnd”, had similar mechanisms (perma-death and so on). But I still think that element of the game being very hard but also, within the context of its rules, very fair is an interesting one.

That, I would argue, provides it’s own form of consistent ludic narrative, to use a theme that was at play in these posts.

Nathanael

May 29, 2022 at 4:40 am

Oh, an interesting point — on original release, Wizardry *came with a pack of its own graph paper*, conveniently in 10×10 format just like the dungeon. Real hint that you were going to need to map, and exactly how you should map, there.

Nathanael

May 29, 2022 at 4:42 am

Oh, I guess it was 20×20, as you note!

Remillard

September 26, 2023 at 1:25 pm

Apparently, they’re making a update to this much in the way a firm was able to update the graphics for Diablo 2 — more of a porcelain over the game rather than a fundamental rework of it. In D2, you can press a key and effectively play in the original highly pixelated chunky graphics, and freely toggle while you play if you choose.

Doing Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord was an interesting choice for this treatment and I’m not sure it’s going to be worth the investment. For certain I have fond memories of it, but there’s been a lot of water under the bridge, and as these articles point out, while it was an outstanding effort for the time, there’s not a lot there in the final analysis.

If it’s cheap though, I might venture to the nostalgia. I still have my original Apple ][+ box and manual and probably most of the level graphs (Level 4 always was a gigantic pain in the butt due to spell slots, and having to camp to map due to the spinners.)