I rarely play or even see current games; the demands of this historical project of mine simply don’t allow for it. Thankfully, though, being a virtual time traveler does have its advantages. Just when I’m starting to feel a little sorry for myself, having heard about some cool new release I just don’t have time for, I get to experience a game like Ultima Underworld the way a player from its own time would have seen it, and suddenly living in my bubble is worth it.

It really is difficult to convey to non-time travelers just how amazing Ultima Underworld was back in March of 1992. To be able to move freely through a realistically rendered 3D space; to be able to walk up and down inclines, to jump over or into chasms, even to swim in underground streams… no one had ever seen anything like it before. At a stroke, it transformed the hoary old CRPG formula from a cerebral exercise in systems and numbers into an organic, embodied virtual reality. In time, it would prove itself to have been the starting point of a 3D Revolution in gaming writ large, one that would transform the hobby almost beyond recognition by the end of the 1990s. We live now in a gaming future very different from the merger of Silicon Valley and Hollywood which was foreseen by the conventional wisdom of 1992. Today, embodied first-person productions, focusing on emergent experience at least as much as scripted content, dominate across a huge swathe of the gaming landscape. And the urtext of this 3D Future through which we are living is Ultima Underworld.

Given what an enormous technological leap it represented in its day, it feels almost unfair to expect too much more than that out of Ultima Underworld as a game. After all, Blue Sky Productions was working here with a whole new set of affordances, trying to figure out how to put them together in a compelling way. It seems perfectly reasonable to expect that the craftspeople of game design, at Blue Sky and elsewhere, would need a few iterations to start turning all this great new technology into great games.

But it’s in fact here that Ultima Underworld astounds perhaps most of all. This very first example of a free-scrolling 3D dungeon crawl is an absolute corker of a game design; indeed, it’s arguably never been comprehensively bettered within its chosen sub-genre. In almost every one of the many places where they were faced with a whole array of unprecedented design choices, Blue Sky chose the right one. Ultima Underworld is a game, in other words, of far more than mere historical interest. It remains well worth learning to overlook the occasional graphical infelicities of its fairly primitive 3D engine in order to enjoy the wonderful experience that still awaits underneath them.

Needless to say, this isn’t quite the norm among such radically pioneering games. Yet it is a trait which Ultima Underworld shares with the two great earlier pioneers in the art of the dungeon crawl, Wizardry and Dungeon Master. Those games too emerged so immaculately conceived that the imitators which followed them could find little to improve upon beyond their audiovisuals. Just what is it about this particular style of game that yields such success right out of the gate? Your guess is as good as mine.

Regardless, we really should take the time to look at Ultima Underworld‘s gameplay still more closely than we have up to this point. So, today, I’d like to take you on a little tour of the most groundbreaking game of 1992.

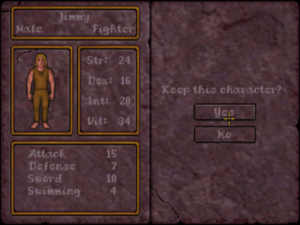

Ultima Underworld puts its most conventional foot forward first. After the conventionally horrid introductory movie, it asks us to create a character, choosing from the usual collection of classes, abilities, and skills. The only thing here that might bring a raised eyebrow to the jaded CRPG player is the demand that we specify our character’s handedness — the first clear indication that this is going to be a much different, more embodied experience than the norm.

As soon as we begin the game proper, however, all bets are off. This looks and feels like no CRPG before it. The grid has disappeared from its dungeon; we can move smoothly and freely in real time, just as if we were really inside its world.

Which isn’t to say that Blue Sky didn’t have to make compromises to bring this free-scrolling 3D environment to life using 1992-vintage hardware. I already discussed one of the compromises in my previous article: the use of affine texture mapping rather than a more rigorous algorithm. This allows the game to render its graphics much faster than it would otherwise be able to, at the expense of a slight wonkiness that afflicts the rendering engine in some situations much more than in others. The second compromise is even more obvious: the actual first-person view fills less than half of the total screen real estate. Simply put, fewer pixels to render means that the rendering can happen that much faster.

Of course, virtually every game ever made is at bottom a collection of compromises with the ideal in a designer’s head. Blue Sky made these two specific ones because they weren’t willing to compromise in other areas. Two months after Ultima Underworld was released, id Software released Wolfenstein 3D, the other great 3D pioneer of 1992. It features a first-person view that fills much more of the screen than that of Ultima Underworld, and with a considerably faster frame rate on identical hardware to boot. But its world is far less interactive. Its levels are all just that — entirely flat — and it won’t even let you look up or down. These were compromises which Blue Sky wasn’t willing to make. A commitment to verisimilitudinous simulation is the dominant theme of Ultima Underworld‘s design. It would go on to become the attribute that, more than any other, distinguishes the games of their later incarnation, Looking Glass Technologies, from the “just run and shoot” approach of id.

In light of the ubiquity of first-person 3D games in the decades since Ultima Underworld, it’s worth examining Blue Sky’s approach to controlling such a game, formulated well before any norms for same had been set in stone. Unlike what followed it, Ultima Underworld‘s preferred approach uses the mouse for everything; this was very much in line with the conventional wisdom of its era, which privileged the relatively new and friendly affordance of the mouse over the keyboard to such an extent that most games used the latter, if they used it at all, only for optional shortcuts. Thus in Ultima Underworld, you move around the world by moving the mouse into the view area and clicking as the cursor changes shape to indicate the direction of travel or rotation.

Blue Sky’s control scheme is a little different from what we may be used to, but it’s not necessarily worse. In fact, the use of the mouse in lieu of the more typical “WASD” keyboard controls for movement has at least one rather lovely advantage: moving the mouse pointer further in a given direction causes you to move faster. The WASD setup, in which each key can only be on or off at any given time, allows for no such sliding scale of movement speed, forcing clumsier solutions like another binary toggle on the keyboard for “run.”

If you just can’t deal with Ultima Underworld‘s preferred movement scheme, however, there are alternatives — always a sign of a careful, thought-through design. You can click directly on the little gray movement buttons down there below the view window. Or, in what was something of a last-minute addition, you can actually using the keyboard in a way very similar to what you may be used to from more recent games. Here, though, the WASD scheme is replaced with SADX, with the “W” key serving as the run toggle. The difference drives some modern players crazy, but it really needn’t do so. Try to get used to moving using only the mouse; you might be surprised at how well it works. (It’s worth noting as well that even id wouldn’t arrive at the WASD standard for quite some time after Ultima Underworld and Wolfenstein 3D. As late as 1993’s DOOM, they would still be mapping the arrow keys to movement by default.)

While left-clicking in the view window lets you move around, right-clicking allows you to manipulate the environment. The vertical row of icons to the left of the view window lets you choose a verb: “talk,” “take,” “examine,” “fight,” or “use,” with the topmost icon leading to the utility menu. If no icon is explicitly selected at a given point, the game intuits a default action when we right-click something in the environment. The end of the short video snippet above shows how elegantly this works in practice. We notice a message scrawled on the wall, and simply right-click it to do the most reasonable thing: to read it.

The video above gives a further taste of the interface in action. Note the ability, so conspicuously absent in id’s contemporaneous games, to look up and down as we move through the world and interact with it. This is accomplished via an exception to the mouse-centric approach. It’s only a little awkward: the “3” key shifts the view upward, “2” centers it vertically, and “1” shifts it downward. It would be at least a couple of years after Ultima Underworld‘s release before any other 3D engine would offer this capability.

This video also illustrates the game’s “paper doll” interface in action, as we pick up objects from the environment and move them into our inventory. The paper doll itself wasn’t new to Ultima Underworld; it had been pioneered by Dungeon Master and long since picked up by the main-line Ultima engines among others. This implementation of it, however, does Dungeon Master one better by living entirely on the main gameplay screen. Indeed, the game has no other screens, with just one exception which we’ll get to momentarily; its commitment to a mode-less interface is even more complete than was Dungeon Master‘s. This, one might even say, is the hidden benefit of that constrained view window. Everything that surrounds it is necessary; the view window might be small, but there is no wasted space anywhere else on the screen. Even what might seem, judging only from the videos above, to be small areas with no purpose actually aren’t, as further playing will reveal. The gray area to the left of the compass will tell us what magical status effects are active; the shelf to the right of the compass is where we will build spells using runes; the crystal at far left, just below the icon bar, shows our current attack strength, and is thus vital for combat. The fact that you aren’t constantly moving between screens does much to enhance the all-pervasive sense that you are there in the dungeon.

Equally important for this effect is a general disinterest in using numbers to represent the current status of your character — or, perhaps better said in light of the game’s commitment to embodiment, your status. While numbers do appear in places — especially if you go looking for them — they’re nowhere near as prevalent as they are in most contemporaneous CRPGs. Your health and mana levels, for instance, are represented graphically by the red and blue vials on the bottom right of the screen — this being another part of the screen you might have initially assumed to be decoration, but which is actually vital.

Later in the video above, we fire up a torch, shedding some welcome light on our surroundings and showing off the game’s advanced lighting model. At the risk of beating a dead horse, I must say, yet again, that no other game of Ultima Underworld’s era or for some time thereafter could match the latter.

Finally, we see something of the game’s physics model in action, as we toss a (useless) skull against the wall. Such kinetic, tactile responsiveness is a far cry from most CRPGs, even as the strength of your character’s throw is indeed affected by his statistics. Dungeon Master, that critical way station beyond Wizardry and Ultima Underworld, pioneered some of this more kinetic approach, but the free-scrolling environment here allows the game to use it that much more effectively.

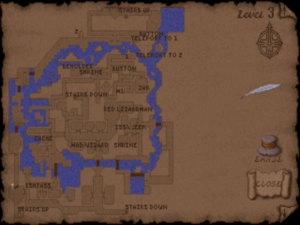

In addition to the torch, we found in that first sack the game’s auto-map. Even as its presence as a physical object in the world emphasizes the game’s ongoing commitment to embodiment, this is actually the only place where the game’s commitment to its mode-less interface falters — but what a spectacular exception it is! I’ve cheated a bit with the screenshot above, choosing a point from much deeper in the game in order to show the auto-map in its full glory. It’s a feature that simply has to be here; the rest of the game, remarkable as it is, would fall apart without it. Cartography — making your own maps on reams of graph paper — had been a standard part of the dungeon-crawl experience prior to Ultima Underworld. Even real-time dungeon crawls like Dungeon Master had left mapping to the player. By removing the discrete grid, however, Ultima Underworld made this style of mapping, if not utterly impossible, at least far too difficult to be any fun even for the dedicated graph-paper-and-pencil crowd. An auto-map was as fundamental to its design as anything in the game.

But if an auto-map of some sort was essential, it certainly wasn’t necessary for its implementation to be this absurdly fantastic. Dan Schmidt, one of the Ultima Underworld developers, has said on several occasions that he considers the seemingly plebeian affordance of the auto-map to be the most impressive single thing in a game that’s bursting at the seams with unprecedented features. There are days when I find myself agreeing.

Whilst ditching the need for graph paper and pencil, Ultima Underworld preserves the foremost pleasure of CRPG cartography: that of seeing all of the blank spaces on your map filled in, enjoying the gradual transformation of the chaotic unknown into the orderly known. The map of each level is lovely to look at as it takes shape. You want to visit every nook and cranny on each one of the levels just to make it as pristine and complete as possible. You’ll even swim the length of the underground streams and lakes, if that’s what it takes to get them completely documented on parchment.

And there’s one final thing the auto-map does which few games — few games ever, mind you — can match: you can make your own notes on the thing, wherever and whenever you want to. Did you notice all of the text on the map above? I did that, not the game. Needless to say, the programming needed to accommodate this — which, incidentally, had already been completed by Doug Church and J.D. Arnold before the rest of the Blue Sky programming team even arrived — couldn’t have been easy. In terms of both design and implementation, Ultima Underworld‘s auto-map really is nothing short of spectacular.

In the video above, we move down the corridor from the game’s starting point. Notice again how we can move slower or faster merely by shifting the position of the mouse within the view window.

We find our first door at the end of the corridor. This door can be opened by a pull chain just beside it, but we rather perversely elect to close it again and then bash it open. Our ability to do so serves as a further illustration of Blue Sky’s commitment to simulation and emergence. The main-line Ultima games as well have doors of variable strength, but, as any dedicated player of those games quickly realizes, Origin Systems had a tendency to cheat in order to fill the needs of a plot that got steadily more complex from installment to installment: many doors — the plot-important doors — are indestructible. You need the correct key to open them, whose acquisition ensures that certain bits of plot are seen before other bits. (As Ron Gilbert once put it, heavily narrative-focused game design ultimately all tends to come down to locks and keys of a literal or metaphorical stripe.)

But Blue Sky, who don’t have the same sort of elaborate pre-crafted plot full of important story beats to worry about, never cheats. Any given door may indeed have a key which you can find, but, if you haven’t found the key, it is at least theoretically possible to pick its lock, to open it using a magic spell, or to simply bash it down. Mind you, doing the last may not do your weapon any favors; keen sword blades were not made to chop through wood. Here we have yet another example of the game’s focus on simulation, albeit one that may feel somewhat less welcome in practical terms than it does in the abstract when your poor misused sword breaks at an inopportune moment — like, say, in the midst of a desperate combat.

The game’s magic system is marked by the same sense of embodied physicality as everything else. Before you can cast spells at all, you’ll need to find a rune bag helpfully left behind by one of the dungeon’s unfortunate earlier explorers. For a long time to come, you’ll be collecting runes to put in it. You combine these runes into “recipes” — most of which are found in the manual — in order to cast spells. In the video above, we place two recently discovered runes into our rune bag and then cast a light spell which can serve as a handy replacement for a torch. (Note that it takes a couple of tries to successfully cast the spell, a sign of our character’s inexperience.) All character classes can use magic to a greater or lesser degree. Even an otherwise “pure” fighter will probably find simple spells that obviate the need to cart around torches or food to be very useful indeed. Thanks to magic, there’s no time limit on the game in the form of depleting resources; by the time you’ve scarfed up all the food in the dungeon, you’ll have long since mastered the “create food” spell.

The rune-based magic system is another aspect of Ultima Underworld that smacks of Dungeon Master (as is, for that matter, the flexible character-development system in which any character can learn to do anything with enough time and effort). But the Blue Sky team has denied looking closely to the older game for inspiration, and we have no reason to doubt their word. So, we’ll have to chalk the similarities up to nothing more than the proverbial great minds thinking alike. If anything, Ultima Underworld‘s magic system is even more elegant than its predecessor’s. Because you’re collecting physical runes, rather than mere spell recipes in the form of scrolls as in Dungeon Master, the sense that everything that matters to the game is an embodied thing in the world is that much more pronounced here.

It should come as no surprise by this point that Ultima Underworld‘s combat system is built along the same lines of embodied physicality. That is to say, you physically swing (or shoot, or throw) your weapon against monsters that are embodied in the same space as you. The video above gives a taste of this, in the form of a battle against a giant rat guarding some choice booty. (Ultima Underworld may be a breathtakingly original design, but some things in the world of CRPGs are timeless. Meeting giant rats as your first opponents is among these.)

Later battles will see you using the environment in all sorts of creative ways: shooting down upon monsters from ledges, blasting them with magic and then running away to recharge your batteries behind a closed door. You can also try to sneak past monsters you’d rather not fight, using not only your character’s innate stealth ability but your own skill at maneuvering through light and shadow. In fact, a sufficiently dedicated pacifist could finish Ultima Underworld while doing surprisingly little killing at all. One of the advantages of the simulation-first approach is that it really does let you play the game your way — possibly even in ways that the game’s designers never thought of.

But Ultima Underworld isn’t all emergent simulation. It does have a plot of sorts, albeit one that you can approach in your own way, at your own speed, and in your own order. You learn soon after arriving in the dungeon that you need to assemble a collection of magic objects. Doing so will occupy your attention for the bulk of the game.

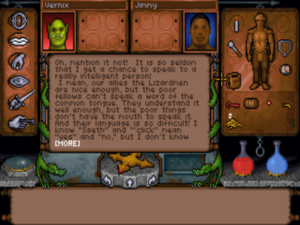

This scavenger-hunt structure may be less innovative than most of the game, but it’s executed with considerable verve. Each level has its own personality and its own inhabitants, living in what feel like credible communities. Importantly, you don’t — or shouldn’t, anyway — indiscriminately slaughter your way through the levels. You need to talk to others, an element that’s notably missing from Wizardry and Dungeon Master. The dungeon’s inhabitants actually remember your treatment of them. An early example of the game’s relationship model, if you will, is provided on the very first level. Two tribes of goblins who hate one another live there in an uneasy symbiosis. Will you ally yourself with one or the other? Or will you try to thread the needle between friend and foe with both, or for that matter go to war with both? The choice is up to you. But choose carefully, for such choices in this game have consequences which you will be living with for a long time to come.

Regular readers of this blog are doubtless aware that I place a high premium on fairness and solubility in games. I’ve gone on record many times saying that a game which is realistically soluble only through a walkthrough cannot by definition be a good game, no matter what other things it does well. In this context, everything would seem to be working against Ultima Underworld. A bunch of MIT whiz kids, all freelancing without recourse to any central design authority, working in an insular environment without recourse to outside play testers… it doesn’t give one much hope for fair puzzles.

Yet, here as in so many other places, Ultima Underworld defies my prejudices and expectations alike. There are perhaps two or three places where the clues could stand to be a little more explicit — certainly no one should feel ashamed to peek at a walkthrough when playing — but there are no egregious howlers here. Take careful notes, take your time, and follow up diligently on all of the clues, and there’s no reason that you can’t solve this one for yourself. Sure, by modern standards it’s an absurdly difficult game. There is no quest log to keep everything neat and tidy for you, and, as a byproduct of its ethos of respecting and empowering its player at every turn, the game will happily let you toss essential quest items into a river, never to be seen again, without saying a word about it. At the same time, though, the utter lack of guardrails can be bracing. If you solve this one, you’ve really accomplished something. And, unlike so many of the games I’ve complained about on this blog, Ultima Underworld never feels like it’s trying to screw you over. It just won’t prevent you from doing so if you decide to screw yourself over.

Only occasionally does the commitment to simulation get in the way of friendly, fair design. To wit: after talking to a character once, trying to elicit the same information again often results only in some variation on “I already told you that!” Dan Schmidt, who was responsible for pulling all of the dialog together, told me that he believed at the time that this was only fair, another way of committing to verisimilitude in all things. Nowadays, I (and he) are more likely to categorize it under that heading of design failures known as “the designer being a jerk just because he can.” Given what a masterpiece Ultima Underworld is on the whole, it’s almost comforting to know that Blue Sky still had a few things to learn about good design.

On the other hand, I really love the way the design uses the game’s virtual space. There are a considerable number of quests and puzzles that span multiple levels in the dungeon, forcing you to retrace your steps and revisit “finished” levels. Another of Ultima Underworld‘s more unique design decisions in comparison with the dungeon-crawl tradition, this does much to give the game a holistic feel, making its dungeon feel like a living place rather than just a series of levels to be solved one after another.

The puzzles themselves are as mode-less as the basic interface. None of them pull you out of the game’s world: no riddles, no mini-games. Instead they work brilliantly within it. There are some wonderfully rewarding puzzles here, such that I hate to spoil them by saying too much about them. Following up on the clues you’re given, you’ll do things that seem like they couldn’t possibly work — surely the game engine can’t be that granularly responsive! — and be shocked and delighted when they actually do. In one fine example, you’ll have to literally learn a new language — okay, a limited subset of it anyway — via clues scattered around the environment. Sometimes challenging and often complex but never unfair, the puzzles will richly reward the effort you put into them.

Perhaps the best example of how the puzzles of Ultima Underworld are integrated into its environment is Garamon, a mysterious personage who often visits your dreams when you sleep. He at first seems like nothing more than a contrived adventure-game clue dispenser, but you gradually realize that he is a real — albeit deceased! — character in the story of the Abyss, and that he has something very personal he wants you to do for him: to give his body a proper burial so he can find peace. When you discover a certain empty tomb, and connect it with the figure from your dreams, the flash of insight is downright moving.

I could go on with yet more praise for Ultima Underworld — praise for, by way of example, its marvelous context-sensitive music, provided by the prolific game composers George “The Fat Man” Sanger and Dave Govett (also the composers of the Wing Commander score among many, many others). Yet I hesitate to cause what may already seem like an overly effusive review to read still more so. I can only hope that my reputation as a critic not overly prone to hyperbole will precede me here when I say that this game truly is a sublime achievement.

I have less — and far less that is positive — to say about the second and final Ultima Underworld game, which bears the subtitle Labyrinth of Worlds. In contrast to its groundbreaking predecessor, it’s a fairly typical sequel, offering as its only mechanical or technical innovation a somewhat larger view window on the 3D environment. Otherwise, it’s more of the same, only much bigger, and not executed quite as well.

The new entity that was known as Looking Glass Technologies — the product of the merger between Blue Sky Productions and Lerner Research — became a much more integral part of the Origin Systems family after the first Ultima Underworld‘s release and commercial success. The result was a plot for the new game that was also better integrated into the Ultima timeline, falling between the two games made by Origin themselves with their own Ultima VII engine in terms of both plot and release chronology. The new interest in set-piece plotting and Ultima lore does the sequel few favors; it rather straitjackets the sense of free-form exploration and discovery that marks the original. Instead of being confined to a single contiguous environment, Ultima Underworld II sends you hopscotching back and forth through its titular “labyrinth of worlds.” The approach feels scattershot, and the game is far less soluble than its predecessor — yet another proof of a theorem which the games industry could never seem to grasp: that a bigger game is not necessarily a better game.

The sequel was created from start to finish in less than nine months, nearly killing the team responsible for it. Origin and Looking Glass’s desire to get a second game out the door is understandable on the face of it; they had a hit on their hands, and wanted to strike while the iron was hot. This they certainly did, but the sequel reportedly sold less than half as many copies as its predecessor — although it should also be noted that even those numbers were enough to qualify it as a major hit by contemporary standards. Still, Paul Neurath, the head of Blue Sky and co-head of Looking Glass, has expressed regret that he didn’t give his people permission and time to make something more formally ambitious. In the future, Looking Glass would generally avoid these sorts of quickie sequels.

While the second game is probably best reserved for the CRPG hardcore and those who just can’t get enough of the experience provided by the first one, the original Ultima Underworld is a must-play. Without a doubt one of the very best CRPGs ever made, it’s even more important for the example it set for gaming in general, showing what heights of flexibility and player-responsiveness could be scaled through the emerging medium of 3D graphics. The pity is that more developers — even many of those who eventually went 3D — didn’t heed the entirety of its example. Countless later games would improve on Ultima Underworld‘s sometimes wonky visuals by throwing out its simplistic affine texture mapping in favor of better techniques, and by blowing up its view window to fill the whole screen. Very few of them, however, would demonstrate the same commitment to what Blue Sky/Looking Glass saw as the real potential of 3D graphics: that of simulating an intuitively emergent world and placing you, the player, inside it. Whether judged in terms of historical importance or by the more basic metric of how much fun it still is to play, Ultima Underworld is and will always remain seminal.

(Ultima Underworld I and II can be purchased from GOG.com.)

Joshua Barrett

February 1, 2019 at 5:32 pm

It’s sort of interesting to see the origin points for id and Looking Glass’s philosophies. One is… definitely a much stronger start than the other: Wolf3D is a game that I don’t think holds up well to modern sensibilities, and certainly not as well as its older brother. id was built on tech and it took some time for them to get to a point where their level design talent was really able to shine. LGS never had *that* problem, at least, although System Shock for one certainly could have used a better control scheme for what it was—that is a game that demands quick responses, and sometimes it feels like the control scheme is a more dangerous enemy than SHODAN.

But the cycle cost for all those extra features was real. SS and Underworld had a much higher base system requirement than even Doom, to my recollection.

Gnoman

February 2, 2019 at 4:30 am

DooM required a 386 with 4MB RAM (minimum) or a 486 with 4MB (recommended). Ultima Underworld required a 386SX with 2MB (minimum), or a 486 (recommended).

In other words, the system requirements were almost identical, which makes sense – in terms of hardware demand, the different focuses of the games were pretty offsetting.

whomever

February 2, 2019 at 2:40 pm

Yeah, and Doom did move somewhat smoother than UU; not to criticize UU but it was doing different tradeoffs. I spent a huge amount of time playing UU but almost none on Doom (but honestly I’m not the target audience, I don’t like FPS)

Joshua Barrett

February 19, 2019 at 9:04 pm

UU was competing with Wolf, not Doom. Doom was contemporary with System Shock.

Steve McCrea

February 1, 2019 at 6:11 pm

scavanger-hunt scructure -> scavenger hunt structure

Nice write up for one of my all-time favourite games!

Jimmy Maher

February 1, 2019 at 7:29 pm

Thanks!

Steve McCrea

February 1, 2019 at 8:24 pm

You missed the second typo there – scructure -> structure :)

Jimmy Maher

February 2, 2019 at 8:26 am

Woops! I was fixing those in the car. (No, not behind the wheel.) Thanks!

Lars

February 1, 2019 at 6:19 pm

verisimilitudious -> verisimilitudinous

Jimmy Maher

February 1, 2019 at 7:30 pm

Thanks!

Jaron

February 1, 2019 at 8:27 pm

Check out Rust by Facepunch Studios!

Keith Palmer

February 2, 2019 at 1:44 am

My knowledge “at the time” of computerized role-playing games was definitely limited, and looking at Ultima Underworld now I want to say I better understand where the interface complications in the Macintosh-only game Pathways Into Darkness (an early game from Bungie Software) came from, although its own 3D engine wasn’t much more advanced than Wolfenstein 3D’s.

Martin

February 2, 2019 at 2:30 pm

Are you going to cover Pathways and Marathon? The “travel through the levels to discover backstory” approach seems an important addition to the basic 3D / first person game.

Jimmy Maher

February 2, 2019 at 4:24 pm

Perhaps in passing, but not in detail, no. Sorry!

xxx

February 2, 2019 at 5:47 pm

I must admit that I’m sorry to hear that. It’s not a terrible thing to skip Pathways into Darkness, which was kind of a wonky game by an inexperienced studio. It shows its age very badly today. But Marathon was actually a rather significant game at the time because it was one of the earliest — and, I’d argue, the most successful — attempt to marry storytelling and first-person shooter gameplay. It had the same sort of “get into a flow state while running around and shooting things” gameplay as Doom, but had a (for the time) remarkable emphasis on story, giving you reams of text throughout the game which contextualized your actions and complemented the moody, atmospheric environment. It would make a good counterpoint to the discussion around Doom, since it was considered at the time “the thinking man’s Doom,” something more than the popular stereotype of mindless run-and-gun gameplay that attached itself to FPS games. Being released only on the Macintosh didn’t do it any favours, though.

The sequels were also interesting. Marathon 2 was a better game than the original in both gameplay and story, while the third one (Marathon Infinity) was divisive; more ambitious, but also much weirder and tonally different. All of them still hold up very well today.

Joshua Barrett

February 19, 2019 at 9:28 pm

I would dispute that.

Marathon does have an excellent story, and a strong high-concept. But as an FPS? It’s simply not very fun to play through nowadays: the controls are actually sorta bad (although alephone could be to blame for that), for one, but the problem goes deeper than that. Marathon is an FPS, and as GAMES (not as narratives), FPSes live and die on two key elements: Level design and enemy design. Marathon is weak in all three respects.

Levels are a slog. They’re a maze from the start and often the architecture feels impossible to differentiate. It’s easy to get lost. And the typical response is “oh, that’s just how FPSes were back then.” No, it’s not. Doom, Duke… all the classics had distinct, memorable designs in their levels. Marathon didn’t, not really.

And the enemy design. Quick test: how many distinct designs do you come across in the first five levels of Doom? Well, there’s the zombie, the sergeant, the imp, the pinky, the invisible pinky… that is five distinct enemies off the bat. In Marathon? I can’t tell you what color each Phor is, I can’t tell you the difference in how they behave. And that’s ALL you’re fighting 90 percent of the time early on.

So yeah. Marathon is a great story wrapped in a mediocre game. I can’t recommend a game when reading its dialogue would give you the best of the experience.

But hey, it’s free, and you’re not me. So I invite everyone to judge for themselves.

anonymous

February 3, 2019 at 8:09 am

You’ve got several references to ‘solubility’ or variants thereof as a quality you look for in games. I doubt you mean their ability to dissolve in a medium. Perhaps ‘solvability’ is what you meant?

xxx

February 3, 2019 at 8:20 am

Nope, that’s a perfectly cromulent usage of “soluble”.

2. Susceptible of being solved; as, a soluble algebraic problem; susceptible of being disentangled, unraveled, or explained; as, the mystery is perhaps soluble. “More soluble is this knot.” –Tennyson. [1913 Webster]

Jimmy Maher

February 3, 2019 at 9:21 am

Yes, the usage is perhaps a little archaic, but not incorrect. I prefer it to solvability, myself, which I find kind of an ugly word.

These two linguistic roots have an interesting linkage. The word “solution” in quite a number of European languages can mean both a liquid solution and a solution to a problem. And at one time, “solvable” meant what “solvable” means today in English. Kind of like “disinterested” and “uninterested” — the meaning has kept going back and forth.

Joe

February 3, 2019 at 7:11 pm

I keep wanting to like this game more than I do, but I expect at some level it’s because I can’t deal well with the control scheme. I simply do not have a computer that has a physical mouse with multiple buttons anymore, at least not anywhere that I sit at for hours on end to play games. I do all of my “adventure” gaming on the couch with a Mac laptop. I’ve even become quite good with the various contriol-keys to simulate second buttons! But this game requires a level of agility with multiple mouse buttons and movements that I cannot capture on my poor laptop. If I were playing on a more historically accurate system, I may feel quite different.

And btw, I really feel for you about living in the past. On the bright side, my wife is very happy that my video game bills have gone way down these past couple of years…

Jimmy Maher

February 4, 2019 at 12:40 pm

Yes, some vintage games — perhaps most notably point-and-click graphic adventures — play surprisingly well on the couch with a laptop and trackpad. Others somewhat less so. I play a lot of the latter type on the television through our media-center PC. It helps that my wife likes to play with sometimes, although she has even less patience than I do for poor design and bad writing. (But then, the games we play together are just idle entertainment for her, not part of an ongoing research project, as they are for me.)

Bmp

February 3, 2019 at 8:02 pm

It’s quite hard to list all of Ultima Underworld’s accomplishments, they’re just so many. I’ve only recently become a fan of this game, and now I wish there were more games like it.

The sense of exploration is just great. Large, interconnected levels with lots of little thematic areas. A great automap where you can write your own notes. Writing down clues, experimenting with the magic runes. Fun NPC conversations that are neither too wordy nor bogged down with Lore.

The biggest flaw, IMO, is that combat is quite easy and you don’t have to employ all the tactical possibilities that the game offers. The CRPGAddict came to the same conclusion here: http://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2018/03/ultima-underworld-won.html

Regarding the grid, to be precise, Ultima Underworld still uses a grid – a tilemap – for its levels, but the walls can be angled at 45 degrees in addition to the usual 90 degree angles (as can be seen from the automap), and the floors can be sloped. This level format is still a far cry from the far more versatile level format of Doom. Regrettably, Looking Glass kept their tilemap-based level format even for System Shock and Terra Nova, when it was quite outdated.

“You can also try to sneak past monsters you’d rather not fight, using not only your character’s innate stealth ability but your own skill at maneuvering through light and shadow. In fact, a sufficiently dedicated pacifist could finish Ultima Underworld while doing surprisingly little killing at all.”

I think it’s not really possible to sneak past most enemies undetected. At least I couldn’t make it work, and I couldn’t discern any effect of light and shadow either – even when not using any light source, the enemies notice you. It seems to be possible in only a few situations, for example with the Fire Elementals when using the Invisibility spell. This feature doesn’t seem to have quite worked out as the developers intended. You can usually simply run past any enemies, though, since you’re so much faster than them.

“the sequel reportedly sold less than half as many copies as its predecessor”

I wonder what the reason for that was. It seems that it was extremely well received in magazine reviews, and while I agree with your criticism that it feels less coherent due to the separate levels/worlds, I can’t imagine that this was a cause for the lower commercial success.

Jimmy Maher

February 4, 2019 at 12:51 pm

While there is a grid underlying the technology — I believe I heard somewhere that the designers even drew out the dungeon levels on graph paper in the beginning — movement is completely free from the player’s perspective. Didn’t want to get too far down in the weeds there. ;)

Ultima Underworld II’s commercial performance was actually fairly typical for a quick sequel to a hit game. The same scenario played out for everything from Ultima Underworld’s near contemporary Eye of the Beholder to the original Zork trilogy from the dawn of the 1980s. A competently executed more-of-the-same-style sequel has an all but guaranteed sales floor, which explains why risk-averse publishers were always so eager to bring them out. Yet the same publishers took perhaps less note of the fact that the same sequel also comes with something of a sales ceiling. Faced with two extremely similar experiences, most gamers will, sensibly enough, opt for number one before number two. And a substantial portion of those that do — even those that really loved the first game — will just never get around to buying the second one.

That’s probably the biggest factor. That said, I also think a bit of Ultima fatigue was beginning to set in by 1993, thanks to Origin’s flooding the market with product sporting the name. (Some of this Ultima ennui can perhaps be seen even in the case of Ultima VII, whose critical and commercial reception was nowhere near as uniformly positive in 1992 as the game’s towering modern reputation might lead one to believe. There was, after all, a reason Origin decided to totally remake the formula with Ultima VIII…)

Bmp

February 4, 2019 at 3:45 pm

“Ultima Underworld II’s commercial performance was actually fairly typical for a quick sequel to a hit game.” “Faced with two extremely similar experiences, most gamers will, sensibly enough, opt for number one before number two. And a substantial portion of those that do — even those that really loved the first game — will just never get around to buying the second one.”

That’s a very good point. But on the other hand, there are games where this didn’t happen, such as Doom 1 & Doom 2, Quake 1 & Quake 2, and series like Call of Duty and Assassin’s Creed. It doesn’t seem to me that UU2 is less developed relative to UU1 than one game from these series is relative to its predecessor.

If we disregard the hindsight we gain from today’s knowledge about UU2’s sales, developing UU2 as a quick sequel might have been worth the try. It might have been one of those gold mines where the players will buy yearly sequels. It just turned out that it wasn’t.

These are just some vague ideas, but I’m under the impression that Looking Glass games, as great as they are, do not quite instill a hunger for more content like real “evergreen” games do, for lack of a better description. (Except maybe Thief 1 & 2.) In context of today’s situation where Immersive Sims reportedly have somewhat middling sales prospects, maybe this is one aspect that needs to be improved somehow.

Jimmy Maher

February 4, 2019 at 4:04 pm

We do want to be a little careful here. Ultima Underworld II likely sold over 200,000 copies, at a time when a hit was a game that sold 100,000 copies. It wasn’t just “worth a try”; it actually did make a lot of money, especially considering the short development cycle using mostly existing technology. Its numbers pale only in comparison to the first game.

Bmp

February 4, 2019 at 7:44 pm

My wording was misleading – I meant to say that if the choice was between a close sequel with less than one year of development time and a more ambitious sequel with a far longer dev time, then I think choosing the close sequel wasn’t a wrong decision per se, as there are examples where close sequels were more successful than the original game.

With hindsight, a more ambitious sequel might have been more successful, and we might have gotten Ultima Underworld 3 and further sequels.

Thief II, with 6 months more dev time than UU2 (going by release dates), seems to have been commercially successful to a roughly similar degree as Thief 1 if I’m interpreting Wikipedia correctly. (But the royalties came too late to save Looking Glass). It also seems rather like a close sequel to me, but of course these definitions are very fuzzy.

Paul

February 4, 2019 at 9:05 am

First comment after long time of reading. Sorry it’s going to be critical of your arguments… so first off, thanks for an amazing writeup on two of my all-time favorites, both of which I played multiple times and both of which still hold up well today IMO!

I don’t agree that Underworld 2 did nothing but expand the view window and streamline the interface a bit. In my opinion it clearly shows the competence and confidence the designers had gained by this point, and the ways they put their engine to use in order to convey a plethora of new experiences. The game feels much more involved to me, much more refined in the way that it lets you experience a greater story your own way (while the “plot” in UW1 feels much more like an afterthought to me).

Granted, it also relies less on emergent gameplay, but it manages to provide an ongoing and developing plot while also leaving you a lot of freedom to explore. UW2’s use of flags for many different parts of the plot is excellent, and you rarely feel constrained in what you can do, or at a loss for what you should be doing, even while the game certainly doesn’t do any handholding.

But in other regards, too, the game treads new ground:

– I particularly like how the level design developed – although, granted, some of the worlds you visit during your travels are somewhat limited in that regard (Prison Tower being the most egregious example – you visit your first alternate world, and it is cramped, uniform, linear and extremely simple… bad choice there). But otherwise, there are many shortcuts to be unlocked, many areas to keep in mind for later when you’re more powerful, many new puzzles and navigational hazards to be solved (or sidestepped, as the case may be).

– The combat is harder and consequently feels more rewarding and more like an important part of the game. Buffing and debuffing spells actually have a place in the game now, and better equipment as well as higher combat skill values are felt more. It’s still possible to sidestep or outrun many or most enemies, which is a good thing of course.

– The leveling cap (or at least the learning point cap) was done away with, which is IMO very important in a game featuring many useful skills (most of which could not be maxed out in the predecessor with its low leveling cap).

– There are many more useful (or fun, such as the bouncing boots) magic items, and a slightly stronger focus on stuff to actually do with your money.

– The lack of magical flight aside from a few potions makes it less easy to simply skip interesting stuff.

More than anything else, however, I applaud the designers’ efforts to actually create a labyrinth of worlds, in which every world you visit has a unique sense of place, a unique aesthetic, and a unique atmosphere. In this, the designers have integrated dialogue into their game more (Prison Tower would be boring level design-wise, but through the dialogue, it stands out at least a little bit better), but it goes beyond only that: most worlds have notably different sub-goals, and notably different difficulties preventing you from reaching them.

Some offer even more than that. For instance, Pits of Carnage at first glance seems like it’s mostly about defeating guys in imaginatively realized elemental-themed arenas, and then killing the pitboss to get his magic goodie… but then you realize that hidden in the hard-as-nails maze beyond the actual fighting pits, there dwell several plot-critical NPCs!

The atmosphere varies a lot, as well: in the Ice Caves you are an archeologist in a hostile, but fun environment with ice skating and lever puzzles, leading to the discovery of a lost civilization; Scintillus breathes loneliness and futility as you take the test to graduate from an academy that no longer exists; Killorn Keep is dangerous through intrigue and wickedness at court; Talorus is whacky as hell, but follows its own consistent inner logic; I could go on.

No, I really, really could. UW2 is one of the best games ever made, and while it may stand on the shoulder of the giant that was its predecessor, it does manage to see further.

Iffy Bonzoolie

July 5, 2020 at 3:03 am

I don’t have a well-researched argument, but I agree that the design of UU2 was better than UU1. If UU1 didn’t exist, you wouldn’t hold it against 2. But 2 really refined the format into a better game.

The hub-and-spoke design of UU2 was easier for the player to navigate, both physically and conceptually. We’ve seen a lot of games use this model to great effect.

While I agree that shoehorning the game into the Ultima universe is not better for the game, if being in the Ultima universe is a fait accompli, then UU2 does a much better job of it.

The different worlds allowed for a wider variety of environments than a strict descent 10 levels into a dungeon.

I also think the plot in 2 kept you moving along smoothly, and there were few places to take you out of the flow by letting you get stuck or wondering what to do next.

It wasn’t revolutionary, how could it be? But I actually expect and want sequels to be evolutionary and it succeeded in that.

Steven Marsh

February 5, 2019 at 7:36 pm

You ask, “What is it about this particular style of game that yields such success right out of the gate?”

My guess is that design decisions on these games are often of the sort “should [X] be 10 or 20?” or “Should this element be on the screen or in a sub-menu?” And by prototyping and actually playing the game, developers are able to see what’s fun and works very quickly, and able to make essential adjustments. (With these sorts of games, I bet you can usually tell if a design element is “fun” within a handful of minutes by trying it . . . and trying a different track or variable could be equally fast.)

Compare this with adventure games, where the need to work in parallel on design decisions, art assets, and storylines often combine in ways that are devilishly difficult to disentwine. If the developers determined Deadline would’ve been better-suited for a plot-based timeline (like Ballyhoo) instead of a clock-based one, or Maniac Mansion‘s creators had decided that a Use/Look interface was better than the 12-command menu, it would’ve been prohibitively difficult/expensive to fix that.

At least, that’s my best guess . . . :-)

Chet Bolingbroke

February 8, 2019 at 5:22 am

This pair of articles are some of the best game-related writing I’ve ever seen. Thank you as always for the unparalleled depth that you offer.

Matt Tyson

October 1, 2020 at 8:40 pm

What do you know about game writing? :D

But seriously, agreed: great article.

Pog

February 8, 2019 at 10:54 pm

You should play the last Zelda. Just this game. You will be happy.

Corey Cole

February 13, 2019 at 11:08 pm

Great article on one of my favorite 1990’s games! I’m surprised that Wolfenstein 3D came out after UU – I remember discussions with Lori about how wonderful it would be to use an FPS engine to make a role-playing game. Then when UU came out, we were delighted how well they made that idea work.

In fact, a couple of years later, maybe about the time we were talking to Brenda Sinclair about having us make a Wizardry game, I corresponded with Paul Neurath about possibly licensing the UU engine to make a new RPG. Paul warned me against it, saying that the source code was nasty – spaghetti code held together with string and chewing gum, so to speak. Regardless of what it might have taken to get the game to work, the wonder is that of the dancing bear – It did work, and it worked well enough to make players feel they were there in those caves. As you say, they made an amazing number of correct decisions in such a complex project!

We certainly wanted more UU-like games to play with new settings and stories, but I was disappointed with UU2. I thought at the time that it was probably an Uncanny Valley situation. By using known characters from Ultima such as Iolo and Dupre in such an immersive environment, I expected them to *be* those characters. Instead I found that they each had only a few lines of pat dialogue, in some cases at odds with their characters in previous Ultima games. It broke the immersion instead of adding to it.

Lt. Nitpicker

February 17, 2019 at 6:04 pm

(It’s worth noting as well that even id wouldn’t arrive at the WASD standard for quite some time after Ultima Underworld and Wolfenstein 3D. As late as 1993’s Doom, they would still be mapping the arrow keys to movement by default.)

Worth noting that id was still setting arrow keys for movement by default in 1997’s Quake II, although it shipped with a optional thresh.cfg file, thresh being the nickname of the player who popularized the scheme.

Jonathan "J.D." Arnold

March 25, 2019 at 1:53 pm

There’s a reason the levels all have their own personality – we all got to design a level! IIRC, my level is actually the one you pictured – level 3, with the river going through it. Definitely one of the best parts of working on UU.

Wolfeye M.

October 25, 2019 at 3:20 pm

I love dungeon crawlers, but I missed out on Ultima Underwood by virtue of being 5 or 6 years old at the time of release, and not having a computer. It looks really cool, I’ll have to check it out. Gotta love GOG for making classic games like UU available to play for gamers like me who didn’t get to play them when they first came out.

Jonathan O

February 8, 2021 at 10:08 pm

“Blue Sky, who don’t have the same sort of eleborate pre-crafted plot…” -> “Blue Sky, who don’t have the same sort of elaborate pre-crafted plot…”

Jimmy Maher

February 9, 2021 at 3:03 pm

Thanks!

Tim Kaiser

October 2, 2021 at 4:51 am

I always preferred the games with loose plots that make you figure out everything yourself, rather than with ones that have heavy story elements that drag you from point A to point B to point C based on where the story wants you to go.

Ultima Underworld 1 kept up with the former style, as did all the Ultima games. You are given a vague quest, “Find and rescue the princess” and you are off on your own devices. Of course it is much more complicated than that but it gives the player much more agency as you are the one driving the plot, rather than the plot driving you.

Daniel

January 4, 2025 at 1:33 am

You mention the ability to do things *If no icon is explicitly selected at a given point…*. This is what the manual calls the ‘default mode’, but your description doesn’t do it justice, and the videos don’t showcase it.

Other than combat, you can do everything you need to do within the default mode, and the game controls much more smoothly that way. Right click is always look, the one contextual action is right button drag. To quote the manual: ‘Eventually, however, perhaps even before you complete this tutorial, you will want to try the icon-less default interface’.