One of the places we ran the “Can a computer make you cry?” [advertisement] was in Scientific American. Scientific American readers weren’t even playing videogames. Why the hell are you wasting any of this really expensive advertising? You’re competing with BMW for that ad.

— Trip Hawkins (EA Employee #1)

Consumers were looking for a brand signal for quality. They didn’t lionize the game makers as these creators to fawn over. They thought of the game makers almost as collaborators in their experience. So apostatizing didn’t make sense to the consumers.

— Bing Gordon (EA Employee #7)

In the ’80s that was an interesting experiment, that whole trying-to-make-them-into-rock-stars kind of thing. It was certainly a nice way to recruit top talent. But the reality is that computer programmers and artists and designers are not rock stars. It may have worked for the developers, but I don’t think it had any impact on consumers.

— Stewart Bonn (EA Employee #19)

One of the stories that gamers most love to tell each other is that of Electronic Arts’s fall from grace. If you’re sufficiently interested in gaming history to be reading this blog, you almost certainly know the story in the broad strokes: how Trip Hawkins founded EA in 1982 as a haven for “software artists” doing cutting-edge work; how he put said artists front and center in rock-star-like poses in a series of iconic advertisements, the most famous of which asked whether a computer could make you cry; how he wrote on the back of every stylish EA “album cover” not about EA as a company but as “a collection of electronic artists who share a common goal to fulfill the potential of personal computing”; and how all the idealism somehow dissipated to give us the EA of today, a shambling behemoth that crushes more clever competitors under its sheer weight as it churns out sequel after sequel, retread after retread. The exact point where EA became the personification of everything retrograde and corporate in gaming varies with the teller; perhaps the closest thing to a popular consensus is the rise of John Madden Football and EA Sports in the early 1990s, when the last vestiges of software artistry in the company’s advertisements were replaced by jocks shouting, “It’s in the game!” Regardless of the specifics, though, everyone agrees that It All Went Horribly Wrong at some point. The story of EA has become gamers’ version of a Biblical tragedy: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

Of course, as soon as one starts pulling out Bible quotes, it profits to ask whether one has gone too far. And, indeed, the story of EA is often over-dramatized and over-simplified. Questions of authenticity and creativity are always fraught; to imagine that anyone is really in the arts just for the art strikes me as hopelessly naive. The EA of the early 1980s wasn’t founded by artists but rather by businessmen, backed by venture capitalists with goals of their own that had little to do with “fulfilling the potential of personal computing.” Thus, when the software-artists angle turned out not to work so well, it didn’t take them long to pivot. This, then, is the history of that pivot, and how it led to the EA we know today.

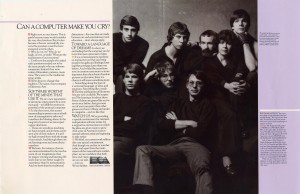

Advertising is all about image making — about making others see you in the light in which you wish to be seen. Without realizing that they were doing anything of the sort, EA’s earliest marketers cemented an image into the historical imagination at the same time that they failed in their more practical task of crafting a message that resonated with the hoped-for customers of their own time. The very same early EA advertising campaign which speaks so eloquently to so many today actually missed the mark entirely in its own day, utterly failing to set the public imagination afire with this idea of programmers and game designers as rock stars. When Trip Hawkins sent Bill Budge — the programmer of his who most naturally resembled a rock star — on an autograph-signing tour of software stores and shopping malls, it didn’t lead to any outbreak of Budgomania. “Nobody would ever show up,” remembers Budge today, still wincing at the embarrassment of sitting behind a deserted autograph booth.

Nor were customers flocking into stores to buy the games EA’s rock stars had created. Sales remained far below initial projections during the eighteen months following EA’s official launch in June of 1983, and the company skated on the razor’s edge of bankruptcy on multiple occasions. While their first year yielded the substantial hits Pinball Construction Set, Archon, and One-on-One, 1984 could boast only one comparable success story, Seven Cities of Gold. Granted, four hits in two years was more than plenty of other publishers managed, but EA had been capitalized under the expectation that their games would open up whole new demographics for entertainment software. “The idea was to make games for 28-year-olds when everybody else was making games for 13-year-olds,” says Bing Gordon, Trip Hawkins’s old university roommate and right-hand man at EA. When those 28-year-olds failed to materialize, EA was left in the lurch.

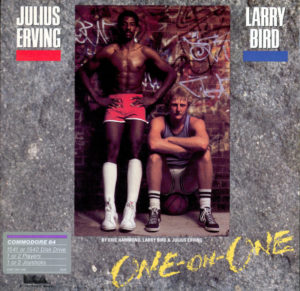

For better or for worse, One-on-One is the spiritual forefather of the unstoppable EA Sports lineup of today.

The most important architect of EA’s post-launch retrenchment was arguably neither Trip Hawkins nor Bing Gordon, but rather Larry Probst, who left the free-falling Activision to join EA as vice president for sales in 1984. Probst, who had worked at the dry-goods giants Johnson & Johnson and Clorox before joining Activision, had no particular attachment to the idea of software artists. He rather looked at the business of selling games much as he had that of selling toilet paper and bleach. He asked himself how EA could best make money in the market that existed rather than some fanciful new one they hoped to create. Steve Peterson, a product manager at EA, remembers that others “would still talk about how we were trying to create new forms of entertainment and break new boundaries.” But Probst, and increasingly Trip Hawkins as well, had the less high-minded goal of “going public and being a billion-dollar company.”

Probst had the key insight that distribution, more so than software artists or perhaps even product quality in the abstract, was the key to success in an industry that, following a major downturn in home computing in general in 1984, was only continuing to get more competitive. EA therefore spurned the existing distribution channels, which were nearly monopolized by SoftSel, the great behind-the-scenes power in the software industry to which everyone else was kowtowing; SoftSel’s head, Robert Leff, was the most important person in software that no one outside the industry had ever heard of. Instead of using SoftSel, EA set up their own distribution network piece by painful piece, beginning by cold-calling the individual stores and offering cut-rate deals in order to tempt them into risking the wrath of Leff and ordering from another source.

Then, once a reasonable distribution network was in place, EA leveraged the hell out of it by setting up a program of so-called “Affiliated Labels” — other publishers who would pay EA instead of a conventional distributor like SoftSel to get their products onto store shelves. It was a well-nigh revolutionary idea in game publishing, attractive to smaller publishers because EA was ready and able to help out with a whole range of the logistical difficulties they were always facing, from packaging and disk duplication to advertising campaigns. For EA, meanwhile, the Affiliated Labels yielded huge financial rewards and placed them in the driver’s seat of much of the industry, with the power of life and death over many of their smaller ostensible competitors.

Unsurprisingly, Activision, the only other publisher with comparable distributional clout, soon copied the idea, setting up a similar program of their own. But even as they did so, EA, seemingly always one step ahead, was becoming the first American publisher to send games — both their own and those of others — directly to Europe without going through a European intermediary like Britain’s U.S. Gold label.

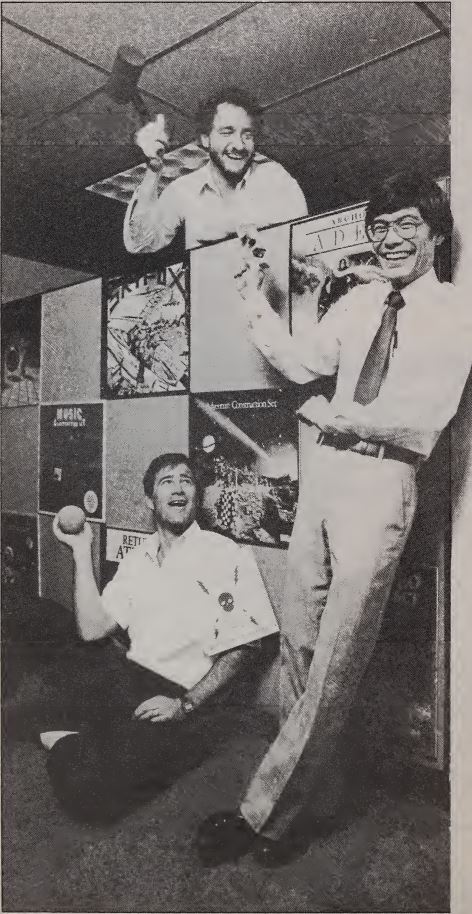

There was always something a bit contrived, in that indelible Silicon Valley way, about how EA chose to present themselves to the world. Here we have Bing Gordon, head of technology Greg Riker, and producer Joe Ybarra indulging in some of the creative play which, an accompanying article is at pains to tell us, was constantly going on around the office.

Larry Probst’s strategy of distribution über alles worked a treat, yielding explosive growth that more than made up for the company’s early struggles. In 1986, EA became the biggest computer-game publisher in the United States and the world, with annual revenues of $30 million. Their own games were doing well, but were assuming a very different character from the “simple, hot, and deep” ideal of the launch — a phrase Trip Hawkins had once loved to apply to games that were less stereotypically nerdy than the norm, that he imagined would be suitable for busy young adults with a finger on the pulse of hip pop culture. Now, having failed to attract that new demographic, EA adjusted their product line to appeal to those who were already buying computer games. A case in point was The Bard’s Tale, EA’s biggest hit of 1985, a hardcore CRPG that might take a hundred hours or more to complete — fodder for 13-year-olds with long summer vacations to fill rather than 28-year-olds with jobs and busy social calendars.

If “simple, hot, and deep” and programmers as rock stars had been two of the three pillars of EA’s launch philosophy, the last was the one written into Hawkins’s original mission statement as “stay with floppy-disk-based computers only.” Said statement had been written, we should remember, just as the first great videogame fad, fueled by the Atari VCS, was passing its peak and beginning the long plunge into what would go down in history as the Great Videogame Crash of 1983. At the time, it certainly wasn’t only the new EA who believed that the toy-like videogame consoles were the past, and that more sophisticated personal computers, running more sophisticated games, were the future. “I think that computer games are fundamentally different from videogames,” said Hawkins on the Computer Chronicles television show. “It becomes a question of program size, when you want to know how good a program can I have, how much can I do with it, and how long will it take before I’m bored with it.” This third pillar of EA’s strategy would take a bit longer to fall than the others, but fall it would.

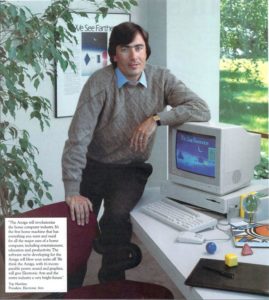

The origins of EA’s loss of faith in the home computer in general as the ultimate winner of the interactive-entertainment platform wars can ironically be traced to their decision to wholeheartedly endorse one computer in particular. In October of 1984, Greg Riker, EA’s director of technology, got the chance to evaluate a prototype of Commodore’s upcoming Amiga. His verdict upon witnessing this first truly multimedia personal computer, with its superlative graphics and sound, was that this was the machine that could change everything, and that EA simply had to get involved with it as quickly as possible. He convinced Trip Hawkins of his point of view, and Hawkins managed to secure Amiga Prototype Number 12 for the company within weeks. In the months that followed, EA worked to advance the Amiga with if anything even more enthusiasm than Commodore themselves: developing libraries and programming frameworks which they shared with their outside developers; writing tools internally, including what would become the Amiga’s killer app, Deluxe Paint; documenting the Interchange File Format, a set of standard specifications for sharing pictures, sounds, animations, and music across applications. All of these things and more would remain a part of the Amiga platform’s basic software ecosystem throughout its existence.

When the Amiga finally started shipping late in 1985, EA actually made a far better public case for the machine than Commodore, taking out a splashy editorial-style advertisement just inside the cover of the premiere issue of the new AmigaWorld magazine. It showed the eight Amiga games EA would soon release and explained “why Electronic Arts is committed to the Amiga,” the latter headline appearing above a photograph of Trip Hawkins with his arm proprietorially draped over the Amiga on his desk.

But it all turned into an immense disappointment. Initially, Commodore priced the Amiga wrong and marketed it worse, and even after they corrected some of their worst mistakes it perpetually under-performed in the American marketplace. For Hawkins and EA, the whole episode planted the first seeds of doubt as to whether home computers — which at the end of the day still were computers, requiring a degree of knowledge to operate and associated in the minds of most people more with work than pleasure — could really be the future of interactive entertainment as a mass-media enterprise. If a computer as magnificent as the Amiga couldn’t conquer the world, what would it take?

Perhaps it would take a piece of true consumer electronics, made by a company used to selling televisions and stereos to customers who expected to be able to just turn the things on and enjoy them — a company like, say, Philips, who were working on a new multimedia set-top box for the living room that they called CD-I. The name arose from the fact that it used the magical new technology of CD-ROM for storage, something EA had been begging Commodore to bring to the Amiga to no avail. EA embraced CD-I with the same enthusiasm they had recently shown for the Amiga, placing Greg Riker in personal charge of creating tools and techniques for programming it, working more as partners in CD-I’s development with Philips than as a mere third-party publisher.

Once again, however, it all came to nought. CD-I turned into one of the most notorious slow-motion fiascos in the history of the games industry, missing its originally planned release date in the fall of 1987 and then remaining vaporware for years on end. In early 1989, EA finally ran out of patience, mothballing all work on the platform unless and until it became a viable product; Greg Riker left the company to go work for Microsoft on their own CD-ROM research.

CD-I had cost EA a lot of money to no tangible result whatsoever, but it does reveal that the idea of gaming on something other than a conventional computer was no longer anathema to them. In fact, the year in which EA gave up on CD-I would prove the most pivotal of their entire history. We should therefore pause here to examine their position in 1989 in a bit more detail.

Despite the frustrating failure of the Amiga and CD-I to open a new golden age of interactive entertainment, EA wasn’t doing badly at all. Following years of steady growth, annual revenue had now reached $63 million, up 27 percent from 1988. EA was actively distributing about 100 titles under their own imprint, and 250 more under the imprint of the various Affiliated Labels, who had become absolutely key to their business model, accounting for some 45 percent of their total revenues. About 80 percent of their revenues still came from the United States, with 15 percent coming from Europe — where EA had set up a semi-independent subsidiary, the Langley, England-based EA Europe, in 1987 — and the remainder from the rest of the world. The company was extremely diversified. They were producing software for ten different computing platforms worldwide, had released 40 separate titles that had earned them at least $1 million each, and had no single title that accounted for more than 6 percent of their total revenues.

What we have here, then, is a very healthy business indeed, with multiple revenue streams and cash in the bank. The games they released were sometimes good, sometimes bad, sometimes mediocre; EA’s quality standards weren’t notably better or worse than the rest of their industry. “We tried to create a brand that fell somewhere between Honda and Mercedes,” admits Bing Gordon, “but a lot of the time we shipped Chevy.” Truth be told, even in the earliest days the rhetoric surrounding EA’s software artists had been a little overblown; many of the games their rock stars came up with were far less innovative than the advertising that accompanied them. The genius of Larry Probst had been to explicitly recognize that success or failure as a games publisher had as much to do with other factors as it did with the actual games you released.

For all their success, though, no one at EA was feeling particularly satisfied with their position. On the contrary: 1989 would go down in EA’s history as the year of “crisis.” As successful as they had become selling home-computer software, they remained big fish in a rather small pond, a situation out of keeping with the sense of overweening ambition that had been a part of the company’s DNA since its founding. In 1989, about 4 million computers were being used to play games on a regular or semi-regular basis in American homes, enough to fuel a computer-game industry worth an estimated $230 million per year. EA alone owned more than 25 percent of that market, more than any competitor. But there was another, related market in which they had no presence at all: that of the videogame consoles, which had returned from the dead to haunt them even as they were consolidating their position as the biggest force in computer games. The country was in the grip of Nintendo mania. About 22 million Nintendo Entertainment Systems were already in American homes — a figure accounting for 24 percent of all American households — and cartridge-based videogames were selling to the tune of $1.6 billion per year.

Unlike many of their peers, EA hadn’t yet suffered all that badly under the Nintendo onslaught, largely because they had already diversified away from the Commodore 64, the low-end 8-bit computer which had been the largest gaming platform in the world just a couple of years before, and which the NES was now in the process of annihilating. But still, the future of the computer-games industry in general felt suddenly in doubt in a way that it hadn’t since at least the great home-computer downturn of 1984. A sizable coalition inside EA, including Larry Probst and most of the board of directors, pushed Trip Hawkins hard to get EA’s games onto the consoles. Fearing a coup, he finally came around. “We had to go into the [console-based] videogame business, and that meant the world of mass-market,” Hawkins remembers. “There were millions of customers we were going to reach.”

But through which door should they make their entrance? Accustomed to running roughshod over his Affiliated Labels, Hawkins wasn’t excited about the prospect of entering Nintendo’s walled garden, where the shoe would be on the other foot, thanks to that company’s infamously draconian rules for its licensees. Nintendo’s standard contract demanded that they receive the first $12 from every game a licensee sold, required every game to go through an exhaustive review process before publication, and placed strict limits on how many games a licensee was allowed to publish per year and how many units they were allowed to manufacture of each one. For EA, accustomed to being the baddest hombre in the Wild West that was the computer-game marketplace, this was well-nigh intolerable. Bing Gordon insists even today that, thanks to all of the fees and restrictions, no one other than Nintendo was doing much more than breaking even on the NES during this, the period that would go down in history as the platform’s golden age.

So, EA decided instead to back a dark horse: the much more modern Sega Genesis, which hadn’t even been released yet in North America. It was built around the same 16-bit Motorola 68000 CPU found in computers like the Commodore Amiga and Apple Macintosh, with audiovisual capabilities not all that far removed from the likes of the Amiga. The Genesis would give designers and programmers who were used to the affordances of full-fledged computers a far less limiting platform than the NES to work with, and it offered the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a brand-new market, as opposed to the saturated NES platform. The only problem was that Sega’s licensing fees were comparable to those of Nintendo, even though they could only offer their licensees access to a much more uncertain pool of customers.

Determined to play hardball, Hawkins had a team of engineers reverse-engineer the Genesis, sufficient to let them write games for it with or without Sega’s official development kit. Then he met with Sega again, telling them that, if they refused to adjust their licensing terms, he would release games on the console without their blessing, forcing them to initiate an ugly court battle of the sort that was currently raging between Nintendo and Atari if they wished to bring him to heel. That, he was gambling, was expense and publicity of a sort which Sega simply couldn’t afford. And Sega evidently agreed with his assessment; they accepted a royalty rate half that being demanded by Nintendo. By this roundabout method, EA became the first major American publisher to support the new console, and from that point forward the two companies became, as Hawkins puts it, “good partners.”

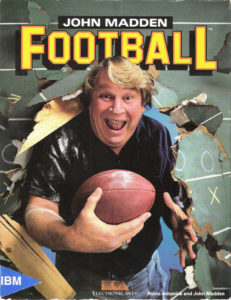

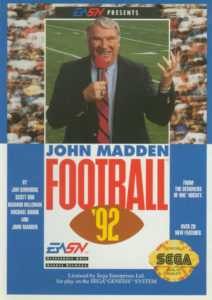

EA initially invested $2.5 million in ten games for the Genesis, some of them original to the console, some ports of their more popular computer games. They started shipping the first of them in June of 1990, ten months after the Genesis itself had first gone on sale in the United States. This first slate of EA Genesis titles arrived in a marketplace that was still starving for quality games, just as Hawkins had envisioned it would be. Among them was the game destined to become the face of the new, mass-market-oriented EA: John Madden Football, a more action-oriented re-imagining of a 1988 computer game of the same name.

John Madden Football debuted as a rather cerebral, tactics-heavy computer game in 1988, just another in an EA tradition of famous-athlete-endorsed sports games stretching back to 1983’s (Dr. J and Larry Bird Go) One-on-One. No one in 1988 could have imagined what it would come to mean in the years to come for either its publisher or its spokesman/mascot, both of whom would ride it to iconic heights in American pop culture.

The Sega Genesis marked the third time EA had taken a leap of faith on a new platform. It was the first time, however, that their faith paid off. About 25 percent of the games EA sold in 1990 were for the Genesis. And when the console really started to take off in 1991, fueled not least by their own games, EA was there to reap the rewards. In that year, four of the ten best-selling Genesis games were published by EA. At the peak of their dominance, EA alone was publishing about 35 percent of all the games sold for the Genesis. Absent the boost their games gave it early on, it’s highly questionable whether the Genesis would have succeeded at all in the United States.

In the beginning, few of EA’s outside developers had been terribly excited about writing for the consoles. One of them remembers Hawkins “reading us the riot act” just to get them onboard. Indeed, Hawkins claims today that about 15 percent of EA’s internal employees were so unhappy with the new direction that they quit. Certainly his latest rhetoric could hardly have been more different from that of 1983:

I knew we had to let go of our attachment to machines that the public did not want to buy, and support the hardware that the public would embrace. I made this argument on the grounds of delivering customer satisfaction, and how quality is in the eye of the beholder. If the customer buys a Genesis, we want to give him the best we can for the machine he bought and not resent the consumer for not buying a $1000 computer.

By this point, Hawkins had finally bitten the bullet and done a deal with Nintendo, who, in the face of multiple government investigations and lawsuits over their business practices, were becoming somewhat more generous with both their competitors and licensees. When games like Skate or Die, a port of a Commodore 64 hit that just happened to be perfect for the Nintendo and Sega demographics as well, started to sell in serious numbers on the consoles, Hawkins’s developers’ aversion started to fade in the face of all that filthy lucre. Soon the developers of Skate or Die were happily plunging into a sequel which would be a console exclusive.

Even the much-dreaded oversight role played by Nintendo, in which they reviewed every game before allowing it to be published, proved less onerous than expected. When Will Harvey, the designer of an action-adventure called The Immortal, finally steeled himself to look at Nintendo’s critique thereof, he was happily surprised to find the list of “suggestions” to be very helpful on the whole, demonstrating real sensitivity to the effect he was trying to achieve. Even Bing Gordon, who had been highly skeptical of getting into bed with Nintendo, had to admit in the end that “the rating system is fair. On a scale from zero to a hundred, where zero meant the system was totally manipulated for Nintendo’s self-interest and a hundred meant that it was absolutely democratic, they’d probably get a ninety. I’ve seen a little bit of self-interest, but this is America, the land of self-interest.”

Although EA cut their Nintendo teeth on the NES, it was on the long-awaited follow-up console, 1991’s Super Nintendo, that they really began to thrive. That machine boasted capabilities similar to those of the Sega Genesis, meaning EA already had games ready to port over, along with developers with considerable expertise in writing for a more advanced species of console. Just in time for the Christmas of 1991, EA released a new version of John Madden Football — John Madden Football ’92 — simultaneously on the Super Nintendo and the Genesis. The sequel had been created, according to the recollections of several EA executives, against the advice of market researchers and retailers: “All you’re going to do is obsolete our old game.” But Trip Hawkins remembered how much, as a kid, he had loved the Strat-O-Matic Football board game, for which a new set of player and team cards was issued every year just before the beginning of football season, ensuring that you could always recreate in the board game the very same season you were watching every Sunday on television. So, he ignored the objections of the researchers and the retailers, and John Madden Football ’92 became an enormous hit, by far the biggest EA had yet enjoyed on any platform — thus inaugurating, for better or for worse, the tradition of annual versions of gaming’s most evergreen franchise. Like clockwork, we’ve gotten a new Madden every single year since, a span of time that numbers a quarter-century and change as of this writing.

All of this had a transformative effect on EA’s bottom line, bringing on their biggest growth spurt yet. Revenues increased from $78 million in 1990 to $113 million in 1991; then they jumped to $175 million in 1992, accompanied by a two-for-one stock split that was necessary to keep the share price, which had been at $10 just a few years before, from exceeding $50. In that year, six of the fifteen most popular console games, across all platforms, were published by EA. Their Sega Genesis games alone generated $77 million, 18 percent more than the entirety of the company’s product portfolio had managed in 1989. This was also the first year that EA’s console games in the aggregate outsold their offerings for computers. They were leaving no doubt now as to where their primary loyalty lay: “The 16-bit consoles are far better for games than PCs. The Genesis is a very sophisticated machine…” The disparity between the two sides of the company’s business would only continue to get more pronounced, as EA’s sales jumped by an extraordinary 70 percent — to $298 million — in 1993, a spurt fueled entirely by console-game sales.

But, despite all their success on the consoles, EA — and especially their founder, Trip Hawkins — continued to chafe under the restrictions of the walled-garden model of software distribution. Accordingly, Hawkins put together a group inside EA to research the potential for a CD-ROM-based multimedia set-top box of their own, one that would be used for more than just playing games — sort of a CD-I done right. “The Japanese videogame companies,” he said, “are too shortsighted to see where this is going.” In contrast to their walled gardens, his box would be as open as possible. Rather than a single new hardware product, it would be a set of hardware specifications and an operating system which manufacturers could license, which would hopefully result in a situation similar to the MS-DOS marketplace, where lots of companies competed and innovated within the bounds of an established standard. The marketplace for games and applications as well on the new machine would be far less restricted than the console norm, with a more laissez-faire attitude to content and a royalty fee of just $3 per unit sold.

In 1991, EA spun off the venture under the name of 3DO. Hawkins turned most of his day-to-day responsibilities at EA over to Larry Probst in order to take personal charge of his new baby, which took tangible form for the first time with the release of the Panasonic “Real 3DO Player” in late 1993. It and other implementations of the 3DO technology managed to sell 500,000 units worldwide — 200,000 of them in North America — by January of 1995. Yet those numbers were still a pittance next to those of the dedicated game consoles, and the story of 3DO became one of constant flirtations with success that never quite led to that elusive breakthrough moment. As 3DO struggled, Hawkins’s relations with his old company worsened. He believed they had gone back on promises to support his new venture wholeheartedly; “I didn’t feel like I was leaving EA, but it turned out that way,” he says today with lingering bitterness. The long, frustrating saga of 3DO wouldn’t finally straggle to a bankruptcy until 2003.

EA, meanwhile, was flying ever higher absent their founder. Under Larry Probst — always the most hard-nosed and sober-minded of the executive staff, the person most laser-focused on the actual business of selling videogames — EA cemented their reputation as the conservative, risk-averse giant of their industry. This new EA was seemingly the polar opposite of the company that had once asked with almost painful earnestness if a computer could make you cry. And yet, paradoxically, it was a place still inhabited by a surprising number of the people who had come up with that message. Most prominent among them was Bing Gordon, who notes cryptically today only that “people’s ideals get tested in the face of love or money.” Part of the problem — assuming one judges EA’s current less-than-boldly-innovative lineup of franchises to be a problem — may be a simple buildup of creative cruft that has resulted from being in business for so long. Every franchise that debuts in inspiration and innovation, then goes on to join John Madden Football on the list of EA perennials, sucks some of the bandwidth away that might otherwise have been devoted to the next big innovator.

In the summer of 1987, when EA was still straddling the line between their old personality and their new, Trip Hawkins wrote the following lines in their official newsletter — lines which evince the keenly felt tension between art and commerce that has become the defining aspect of EA’s corporate history for so many in the years since:

Unfortunately, simply being creative doesn’t always mean you’ll be wildly successful. Van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime. Lots of people would still rather go see Porky’s Revenge IV, ignoring well-produced movies like Amadeus or Chariots of Fire. As a result, film producers take fewer risks, and we get less variety, and pretty soon the Porky’s and Rambo clones are all you can find on a Friday night. Software developers have the same problem. (To this day, all of us M.U.L.E. fans wonder why the entire world hasn’t fallen in love with our favorite game.)

The only way to solve the problem is to do it together. On our end, we’ll keep innovating, researching, experimenting with new ways to use this new medium; on your end, you can support our efforts by taking an occasional risk, by buying something new and different… maybe Robot Rascals, or Make Your Own Murder Party.

You may be very pleasantly surprised — and you’ll help our software artists live to innovate another day.

Did EA go the direction they did because of gamers’ collective failure to support their most innovative, experimental work? Does it even matter if so? The more pragmatic among us might note that the EA of today is delivering games that millions upon millions of people clearly want to play, and where’s the harm in that?

Still, as we look upon this industry that has so steadfastly refused to grow up in so many ways, there remain always those pictures of EA’s first generation of software artists — pictures that, yes, are a little pretentious and a lot contrived, but that nevertheless beckon us to pursue higher ideals. They’ve taken on an identity of their own now, quite apart from the history of the company that once splashed them across the pages of glossy lifestyle magazines. Long may they continue to inspire.

(Sources: the book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay and Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff; Harvard Business School’s case study “Electronic Arts in 1995”; ACE of April 1990; Amazing Computing of July 1992; Computer Gaming World of March 1988, October 1988, and June 1989; MicroTimes of April 1986; The One of November 1988; Electronic Arts’s newsletter Farther from Summer 1987; AmigaWorld premiere issue; materials relating to the Software Publishers Association included in the Brøderbund archive at the Strong Museum of Play; the episode of the Computer Chronicles television series entitled “Computer Games.” Online sources include “We See Farther — A History of Electronic Arts” at Game Developer, “How Electronic Arts Lost Its Soul” at Polygon, and Funding Universe‘s history of Electronic Arts.)

Alex Smith

October 5, 2018 at 4:54 pm

A few points:

1. Bing Gordon was not employee #2, but rather employee #7. Rich Melmon, Dave Evans, Pat Marriott, Stephanie Barrett, and Jeff Burton were all there before him.

2. “1984 could boast only one comparable success story, Seven Cities of Gold.”

Not quite true. Ray Tobey’s Skyfox was also released in 1984 and ultimately sold over 300,000 units. The game is credited by several employees, including Bing, for helping save EA. Now, many of those sales came after it was converted to the C64 in 1985, but the Apple II version did sell well in 1984 according to the Billboard software charts.

3. I think this narrative skews Trip Hawkins views on the console industry a little bit and distorts how the company finally came to the market. As written, there is an implication that Trip was quick to back down from his original vision when faced with the success of Nintendo, but that does not really appear to be the case from the dozen or so interviews I have conducted with EA employees.

Trip was adamantly opposed to the console market due to the control exerted by the manufacturers, and he was not alone among upper management in his aversion to that market. Larry Probst was the one who really wanted in because of the potential profit. The compromise is that EA began licensing some of its games to Konami. When Skate or Die did about 1.2 million units on the NES, Hawkins was faced with a board revolt because of all the money EA was leaving on the table. Hawkins tried to stare down his board, and they threatened to fire him. Only then did he reluctantly move into the console market and develop the plan on how to win back a little bit of that control from Sega.

The above account is told in the book Game Over, and variations of it have been supported by many of my interviews with individuals like Bing Gordon, Stewart Bonn, Don Traeger, and Trip himself. Maybe Trip comes to the same decision on his own without board pressure, as he is a shrewd businessman and Larry was pushing hard, but as it played out he fought the move to console with all of his might until his choice was “enter the console business, or we will find someone who will.”

Jimmy Maher

October 5, 2018 at 6:21 pm

1. Thanks!

2. Given the relative size of the Apple II versus Commodore 64 game markets, I think Skyfox is a success story best reserved for 1985. By 1984, a hit Commodore 64 games was selling several times as many copies as a hit Apple II game, and Skyfox is arguably a game better-suited to the more action-oriented Commodore 64 market anyway.

3. I actually looked at this question pretty hard. I’m a little skeptical of the account in Game Over, given that that book has some other inaccuracies and given the way the various accounts and timelines just don’t quite line up. I suspect that Hawkins’s resistance was stronger to publishing on Nintendo’s console than it was to publishing on consoles in general.

The biggest point of conflict is Hawkins’s claim, stated in his interview in Gamers at Work among other places, that EA’s IPO, which only earned about $10 million, was done specifically to secure funding to reverse-engineer the Sega Genesis, to develop and publish the first slate of games for that platform, and to have a war chest to hand in case EA wound up publishing there without Sega’s permission and had to try to win in court. Obviously, it can’t be the case that Hawkins both did the IPO to secure funding for the console market and was forced to enter the console market against his will by the new investors who came in with the IPO (the latter being the story Sheff tells). If, however, those investors were pushing him to get on the *NES* in addition to the Genesis, it all begins to make a lot more sense.

The other possibility, of course, is that Hawkins is simply mis-remembering or lying. But both strike me as out of character. I’m certainly willing to revisit the issue if you have more insights, but this is my point of view on it right now.

Alex Smith

October 5, 2018 at 7:08 pm

It had been awhile since I read the Game Over account. I think the part in there about the new investors pushing consoles was an error on Sheff’s part. EA always had a strong and opinionated board and already had plenty of VC types on it before the IPO.

The part about the board forcing his hand though, that was confirmed to me by Trip in an interview. Don Traeger also told me how Trip really did not want to enter the console market. The sense I get is that Sega was the lesser of two evils in his mind.

Jimmy Maher

October 5, 2018 at 8:10 pm

Okay, thanks. Added a couple of sentence to indicate that Hawkins was pressured when making the decision.

Alex Freeman

October 5, 2018 at 7:57 pm

Well, that explains a lot.

There’s nothing wrong with that; it’d just be nice if there’d been more room for other kinds of games to succeed. Of course, it could be argued that video games are more creative than ever before thanks to the Internet. The real problem now, though, is all the gems getting buried under the rubble.

David Boddie

October 6, 2018 at 12:18 am

“CD-ROM-based multimedia setup box of their own” (set-top)

The idea of a videogames console as a multimedia appliance was ahead of its time – or perhaps of its time given that CDs had started to become the way to distribute games. I think this idea became much more of a realistic proposition for most people when consoles started to be able to play DVDs and later Blu-ray media.

I’m always intrigued by the CPU architectures used by the consoles from the fifth generation onwards. The cancelled follow-up to the 3DO was to use dual PowerPC 602 CPUs. Both Sony and Nintendo used PowerPC CPUs, but a few years later, so I wonder if the M2 would have been ahead of its time or the odd one out again.

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2018 at 8:14 am

Thanks!

I’d say the idea was definitely *of* its time. There were a lot of people convinced that a multimedia set-top box, capable of playing games but also of running useful informational applications and playing music and even movies, was the all-in-one future of living-room entertainment, destined to replace the specialized game consoles. The 3DO was hardly the only specimen of the breed; see also the CD-I and Commodore’s CDTV.

But what seemed like a perfectly reasonable idea just never happened; the public proved oddly resistant to the concept. DVD players eventually came along to take up some of this space, and videogame consoles soon acquired the ability to play DVD movies as well. So, I guess you could say the concept did come to fruition, only many years later than expected. Part of the problem in the early days was doubtless the fact that the various models of set-top box all lacked the ability to display video with reasonable fidelity, or to fit very much of it on a single CD.

Chris D

October 6, 2018 at 9:43 am

I’d say part of the reason why the 3DO never took off was expense – it was much more expensive than the consoles it was competing with. I’ve seen it argued that the problem with 3DO’s approach whereby anyone could license and release their own console that met the 3DO standard was that it couldn’t be subsidised by game sales in the same way that Sony & Sega’s consoles could. Those companies could take the hit and sell the console at cost price (or at a slight loss), whereas Panasonic or Goldstar would have to make a profit on each unit.

I guess the other problem was the multimedia aspects were not up to scratch – video CDs were not really a significant improvement on VHS, at least not in the same way as DVD was. As soon as a relatively cheap console came along that also functioned as a very capable multimedia player (i.e. the Playstation 2) it was a huge success.

Gnoman

October 6, 2018 at 9:50 pm

The big thing here, as mentioned in an earlier article, is that this is still the era where nobody really knew what to do with all the space a CD offered. Most just used the space for better music (nice, but hardly a game-changer), or else went down the horrible FMV pathline.

Even in the PS1 era, a ton of games only used a small portion of the disc for game data. They’d gotten to the point where a game wouldn’t fit on an affordable cartridge anymore, but the CD was still a vast empty void unless you were doing a lot of cutscenes.

Iffy Bonzoolie

June 28, 2020 at 7:04 am

Note that this did eventually happen. Starting in earnest with the PS3’s Blu-Ray player, game consoles have drifted into home entertainment appliances. Microsoft launched a whole Silverlight-based framework for developing streaming media apps for the Xbox 360. When they launched Xbox One, their OS was designed to be able to run media apps concurrently with games! One could even argue that they forgot they were supposed to be a game console until the Xbox One X.

What still hasn’t happened is interactive video content. Everyone has tried it — Blu-Ray, cable, satellite — and no one seems to really want it. Live voting on Dancing with the Stars is the best application anyone has come up with…

Bernie

October 6, 2018 at 2:12 pm

Hi Jimmy ! This piece has been a joy to read, as usual.

Keep up the excellent work.

Regarding Trip Hawkins’ concept of “software artists” , it probably just didn’t work quite the way he intended because he simply was pushing a little too hard. The music-industry analogy with the album packaging, professional photography and autograph signing was overdone.

The world of electronic gaming had already developed a more “natural” tendency to credit its most talented creators. Case in point : Richard Garriott was a celebrity much earlier than 1983 ; The founding of Activision by programmers seeking recognition (which they got).

There was also the british scene, where programmers were revered and got plenty of press coverage without any overt efforts from the publishers : Braben and Bell (Elite), Jeff Minter, the Stamper brothers.

This was happening even in parallel to Hawkins’ efforts, for example at EA rival Epyx, where people like Jon Freeman, Stephen Landrum and Michael Kosaka came to prominence even though Epyx didn’t even put their names on the packaging or the ads. Gee, they even ended up working for electronic arts.

I vividly remember getting a copy of Skate or Die! for my C64 because I saw the names of Stephen Landrum and Michael Kosaka on the loading screen, not because it came from EA. I was very fond of the work they did for Epyx on the Games series and other titles.

I wholly suscribe to your point that Hawkins’ promotional strategies for the creators were right in the long run, he just needn’t be so fanatical about it. Maybe he should take comfort that nowadays even the Japanese, namely Nintendo and Sega, acknowlege and revere their creative minds: the likes of Miyamoto, Suzuki and Kojima. I still remember the NES days when most games credited the programmers and artists with pseudonyms, or not at all. Maybe Sega was a little more progressive in this regard.

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2018 at 3:38 pm

Your points are well taken, but I would also argue that the *type* of fame Hawkins sought for his designers was not quite the same as that enjoyed by the examples you cite. While it’s certainly true that some developers had a fair measure of name recognition, it was (and still largely is) restricted to the insular culture of hardcore gamers. Trip Hawkins’s big idea was to make games and game developers artistically respectable — and *cool* — among the taste makers of hip culture in general. He didn’t just want to get them recognition. He really did want to make them celebrities — rock stars.

This type of fame, of course, still isn’t enjoyed by game developers even today. The games industry has always had a bit of jealousy and aspiration toward the glitzier, more star-driven cultures of movies and music. In that light, it’s not hard to understand why the rock-star advertisements still speak to so many gamers and game developers today. Those moody, oh-so-hip photographs make for a powerful wish-fulfillment fantasy. But if they continue to inspire people to do interesting work, as they quite clearly have done for many years now, more power to them.

Sniffnoy

October 7, 2018 at 5:36 pm

Hideo Kojima probably comes closest, I’d say…

Alex Freeman

October 7, 2018 at 7:34 pm

I’ve always found the whole “rock star” angle rather strange. I mean, you don’t hear about book authors wanting to be “rock stars”, and I’d say they’re much more like game designers than rock or movie stars are.

whomever

October 8, 2018 at 2:49 am

(replaying to Alex Freeman): An interesting nuance around “rock star” is that it’s become a standard term for some combination of “really good” and “everyone says they are really good”; I’ve heard it use to describe people in fields as diverse as (very much NON games) computer programming and sailboat racing…

Jimmy Maher

October 8, 2018 at 12:38 pm

One amusing irony in pop culture’s appropriation of the term is the fact that a lot of its modern ubiquity is doubtless thanks to Rockstar Games of Grand Theft Auto fame; the games industry’s rock-star envy has, it seems, come full-circle. But the supreme is the way that the world is full of “rock stars” at doing this or that, yet literal rock stars have all but disappeared from the pop-culture landscape; the only ones to really qualify for the label these days are aging legacy acts like U2, whose best years are quite clearly well behind them.

Bernie

October 7, 2018 at 9:03 pm

Yes. Indeed. Thanks again jimmy.

I get your angle now. He was working towards mass-media appeal, not gaming-focused media coverage. He was thinking of People.com rather than IGN.com. Variety and New Yorker rather than CGW or Compute!.

DZ-Jay

October 15, 2018 at 12:02 pm

The reason that sort of fame does not work for game designers and book authors is because it is unearned. Most likely this is due to personality traits.

You see, almost by definition, rock stars and movie actors are /showmen/, and thus are self-selected to express themselves in a larger-than-life manner, and to seek the limelight. The ones who succeed in getting our attention and grasping our fascination are the ones with an innate sense of self-assurance and charisma. Thus, they may be a product of coordinated marketing, but they can indeed play the part (and often relish in it), as it were.

Contrast this to the typical author or game designer, vocations for which charisma and self-assurance are not necessary — and indeed perhaps anathema. Many engineers and authors would rather sit in solitude and do their work, and collect the praises from a distance, rather than be out there calling attention to themselves. In fact, the praise and attention that they often seek is for their work, not for themselves.

Anyway, that’s my opinion, obviously not a hard and fast rule, for there are plenty of exceptions.

dZ.

Bernie

October 6, 2018 at 2:14 pm

Sorry : 4th paragraph – “Electronic Arts” (with capitals) , not “electronic arts” (no disrespect intended)

Bing gordon

October 6, 2018 at 9:10 pm

Don Traeger deserves a lot of credit for the insights about the console market.

Andy Berlin deserves credit for turning the founding team’s aspirations into a cohesive rallying cry; Rich Silverstein for making it visually arresting; and both for the entire record album design and creative strategy. And Jim Nitchall’s for reverse engineering the Genesis.

Trip’s founder’s vision and creative genius made everyone reach a bit higher.

hcs

October 13, 2018 at 7:12 pm

Nits:

“get it on the ground floor”

I’ve usually seen CD-I written CD-i, particularly in recent retrospectives. But it looks like official sources use uppercase in print; I’ve only found Philips using lowercase in a logo, like this: http://www.computinghistory.org.uk/userdata/images/large/76/5/product-107605.jpg

Jimmy Maher

October 14, 2018 at 7:27 am

Thanks!

I looked at the capitalization issue when I first wrote about CD-I. It was, as far as I can see, universally referred to in all caps at least until its release.

Casey Muratori

October 15, 2018 at 3:50 am

Just wanted to mention that the description of “Skate or Die” as a “Commodore 64 game” caught me a little off guard, because I had forgotten that the original arcade game was actually called “720”, and that EA had simply stolen the catch phrase for their skateboarding title. Once I looked it up, it made sense, but it might be worth putting in a parenthetical about 720 in the article to avoid similar confusion for people with failing memories such as my own :)

– Casey

Jimmy Maher

October 15, 2018 at 10:11 am

Thanks, but in this case I’m going to leave it as-is. It’d be a little tough to explain that elegantly in a parenthetical, and I don’t want to go off on a tangent.

Pedro Timóteo

October 15, 2018 at 4:54 pm

720º and Skate or Die are — other than the subject, of course — unrelated games (although, yes, the phrase “skate or die” comes from 720º originally). Or did you mean something else?

Chris Rowley

November 4, 2018 at 8:17 am

Awesome article as always! I was there working retail when EA launched and got to talk to some of their devs later when I worked at IMSATT, the developers of the visual programming environment AmigaVision. This was when EA was so front-and-center with their creative tools as much as they were with the games but after the American market was obviously a lost cause. At the time we agreed Commodore did everything wrong, but that they probably never could have broken through the rising tide of the PC regardless.

I guess what drove me to comment for once was the realties of game publishing today being rooted in EA’s console shift. I understand the bottom-line, but economics offer a lot of options that are being left on the table. The console market offered a larger installed base, but home computer games could still turn a profit. Finding a budget that could be covered by a certain number of sales doesn’t seem to be an option in a swing-for-the-fences mentality that has distanced AAA today so far and eliminated a robust AA that died with the PS2/Xbox/GameCube-era. Is there a way to stem the hire-and-fire single-title crunch at publishers with deep pockets by servicing different price points? Is there any way to carve out a space for Trip’s initial vision within a publisher tilting solely at blockbusters today?

Jimmy Maher

November 4, 2018 at 8:43 am

Many would claim that the indie market and digital distribution have led to a fulfillment of the original EA vision. Certainly there’s a lot more interesting work being done there today than in the risk-averse world of AAA. What I think has been lost is a measure of curation and quality control. When basically anyone can make and release a game — the standards you have to meet to get listed on Steam or the Apple store are pretty minimal at best — you get a lot of unplayable, unbalanced junk. Finding the gems in all this dross can be difficult.

whomever

November 5, 2018 at 12:42 pm

There’s a lots of dross sure, but also lots of great stuff. Just to name 2 modern games that are completely indie (and both of which I happen to play): Cities Skylines, developed in Finland (and with a female lead!) was developed to be the SimCity that SHOULD have been after the disaster of Simcity 2013 (Which was ironically developed by….EA!) Kerbal Space Program is a super fun game that’s also a physics lesson (I have learned more about Orbital Mechanics than I did in any of my Physics classes) developed by a Brazilian with a passion for space living in Mexico city.

Jimmy Maher

November 5, 2018 at 1:16 pm

Oh, sure. Whatever complaints you can make about the state of games today, it’s far healthier than the years immediately before the rise of digital distribution, when conservative publishers like EA threatened to strangle all innovation in the field. For all that I write a blog about the history of games, I’m not at all on the “old games were better” bandwagon. I have no doubt that there’s a wider variety of truly interesting games being made now than ever before.

I’ve heard a lot about both specific games you mention, especially Kerbal Space Program. Return of the Obra Dinn is another one that I’ve had a line of people telling me I need to play. Going to try to squeeze that one in when I go on holiday in a couple of weeks; as an adventure game, it’s a bit less of a potential open-ended time sink. ;)

PJN

December 7, 2018 at 6:16 am

“with the sense of overweening ambition that been a part”

could be

“that had been”

Jimmy Maher

December 7, 2018 at 8:14 am

Thanks!

albertron

April 29, 2021 at 12:51 am

There was a really really great interview with Trip recently (2021) – the guy is still totally on the ball with recent developments, and its interesting to see him describe his guiding philosophy about using multiplayer computer games to improve society, specifically for the less gregarious type personalities (he gives a lot of love to MULE in this too).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5wvX3YNrZAs