I can hardly emphasize enough the influence that war games and tabletop role-playing games (particularly, of course, TSR’s Dungeons and Dragons) had on early computer-based ludic narratives. Sometimes that influence is obvious, as in games like Eamon that explicitly sought to bring the D&D experience to the computer. In other cases it’s more subtle.

Unlike traditional board or even war games, D&D and its contemporaries were marketed not as single products but as a whole collection of experiences, almost a lifestyle choice. Just getting started with the flagship Advanced Dungeons and Dragons system required the purchase of three big hardcover volumes — Monster Manual, Players Handbook, Dungeon Masters Guide — and to this were soon added many more volumes, detailing additional monsters, treasures, gods, character classes, and increasingly fiddly rules for swimming, workshopping, sneaking, thieving, and of course fighting. But most of all there were adventure modules — pre-crafted adventures, actual ludic narratives to be run using the D&D ludic narrative system — by the dozen, meticulously cataloged via an alphanumeric system to help the obsessive keep track of their collection; a trilogy of modules dealing with giants got labelled “G1” through “G3,” a series of modules originating in Britain was labelled with “UK,” etc. Whatever its other advantages, this model was a marketer’s dream. Why sell just one game to your customers when you can lock them into an ever-expanding universe of products?

TSR’s one game / many products approach to marketing and its zeal for cataloging surfaces even amongst early computer-game developers that were not trying to adapt the D&D rules to the digital world. Scott Adams, for instance, numbered each of his adventures, eventually ending up with a canonical dozen. (Other adventures, presumably worthy but not written by the master himself, were published by Adventure International as a sort of official apocrypha in the form of the OtherVentures series.) Players were encouraged to play the adventures in order, as they gradually increased in difficulty; thus could the beginner cut her teeth on relatively forgiving efforts like Adventureland and Pirate Adventure before plunging into the absurdly difficult later games like Ghost Town and Savage Island. On-Line Systems adapted a similar model, retroactively subtitling Mystery House to Hi-Res Adventure #1 when Hi-Res Adventure #2, The Wizard and the Princess, hit the scene. The next game, Mission: Asteroid, which appeared in early 1981, was subtitled Hi-Res Adventure #0 in defiance of chronology, as it was meant to be a beginner’s game featuring somewhat fewer absurdities and unfair puzzles than the norm. These similarities with the D&D approach are in fact more than a marketing phenomenon. Both lines were built on reusable adventuring engines, after all. Just as a group of players would have many different adventures using the core D&D rules set, the Scott Adams or Hi-Res Adventures lines were essentially a core set of enabling “rules” (the engine) applied to many different instances of ludic narrative.

Still, of the developers we’ve looked at so far, the ones who most obviously mimicked the D&D model were, unsurprisingly, the ones who came directly out of the culture of D&D itself: Donald Brown with the Eamon system, and Automated Simulations, developers of the DunjonQuest line that began with Temple of Apshai. J.W. Connelley, the principal technical architect for Automated Simulations, designed for Temple of Apshai a reusable engine that read in data files representing each level of the dungeon being explored. As it did for Scott Adams and On-Line Systems, this approach both made the game more easily portable — versions for the three most viable machines in 1979, the TRS-80, the Apple II, and the Commodore PET, were all available that year — and sped development of new iterations of the concept. These were marketed as part of a unified set of experiences, called DunjonQuest; the alternative medieval-era spelling was possibly chosen to avoid conflict with a litigious TSR, who marketed a board game called simply Dungeon! in addition to the D&D rules.

And iterate Automated Systems did. Two more DunjonQuest games appeared the same year as Apshai. Both Datestones of Ryn and Morloc’s Tower were what Automated Simulations called MicroQuests, in which the character-building elements were removed entirely. Instead the player guided a preset character through a much smaller environment. The player was expected to play many times, trying to build a better score. In 1980 Automated Simulations released the “true” sequel to Apshai, Hellfire Warrior, featuring levels 5 through 8 of the labyrinth that began in that earlier game. They also released two more modest games, Rescue at Rigel and Star Warrior, the first and only entries in a new series, StarQuest, which took the DunjonQuest system into space.

At least from a modern perspective, there is a sort of cognitive dissonance to the series as a whole. The manuals push the experiential aspect of the games hard, as shown by this extract from the Hellfire Warrior manual:

Whatever your background and previous experience, we invite you to project not just your character but yourself into the dunjon. Wander lost through the labyrinth. Feel the dust underfoot. Listen for the sound of inhuman footsteps or a lost soul’s wailing. Let sulfur and brimstone assail your nostrils. Burn in the heat of hellfire, and freeze on a bridge of ice. Run your fingers through a pile of gold pieces, and bathe in a magic pool.

Enter the world of DunjonQuest.

For all that, none of the games has any real plot within the game itself. Neither Apshai nor Hellfire Warrior even has an ending, just endlessly regenerating dungeons to explore and a player character to perpetually improve. And the MicroQuests reward their players only with an unsatisfying final score in lieu of a denouement. Datestones of Ryn has a time limit of just 20 minutes, making it, in spite of the usual carefully crafted background narrative of its manual, feel almost more like an endlessly replayable, almost context-less action game than a CRPG. The gameplay of the series as a whole, meanwhile, strikes modern eyes as most similar to the genre of roguelikes, storyless (or at least story-light) dungeon crawls through randomly generated environments. This, however, is something of an anachronistic reading; Rogue, the urtext of the genre, actually postdates Apshai by a year.

I think we can account for these oddities when we understand that Jon Freeman, the principal game designer behind the systems, is aiming for a different kind of ludic narrative than that of the text adventures of Scott Adams and On-Line Systems. He hopes that, given the background, a description of the environment, a set of rules to control what happens there, and a healthy dose of imagination on the player’s part, a narrative experience will arise of its own accord. In other words, and to choose a term from a much later era, he throws in his lot with emergent narrative. To understand his approach better, I thought we might briefly take a closer look at one of the games, Rescue at Rigel.

Rescue at Rigel draws its inspiration from classic space opera, a genre that had recently been revived by the phenomenal success of the first two Star Wars movies.

In the arenas of our imagination, not all of our heroes (or heroines!) wear rent black armor or shining silver mail, cleave barbarian foes on a wind-swept deck, or face a less clean fate at the hands of some depraved adept whose black arts were old when the world was young. Science fiction propels us about space-faring ships like Enterprise, Hooligan, Little Giant, Millenium Falcon, Nemesis, Nostromo, Sisu, Skylark, and Solar Queen into starry seas neither storm-tossed nor demon-haunted but no less daunting for all that — and lands us on brave new worlds whose shapes and sights and sounds are more plausible — but no less astonishing — then any seen by Sinbad.

The Rescue at Rigel player takes the role of Sudden Smith, a classic two-fisted pulp hero. He is about to beam down to the base of a race of insectoid aliens known as the Tollah, who have captured a group of scientists for “research,” among them Sudden’s girlfriend. The Tollah provide one of the surprisingly few references to events in the broader world outside of fantasy and science-fiction fandom that you’ll find in very early computer games. The leader caste of the Tollah are the “High Tollah,” a clear reference to Ayatollah Khomeini who had recently assumed power in Iran and held 52 Americans hostage there. “High Tollah,” the manual tells us, “are smug, superior, authoritarian, intolerant, narrow-minded, unimaginative, and set in their ways.” In this light, the inspiration for the scientist-rescue scenario becomes clear.

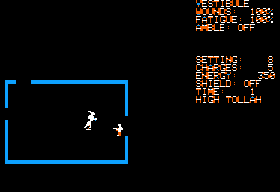

The gameplay involves exploring the conveniently dungeon-like labyrinth of the Tollah base, warding off Tollah and security robots while searching for the ten scientists being held hostage there. It is, like so many CRPGs, essentially a game of resource management; Sudden has limited medkits, limited ammunition, and, most of all, limited energy in the portable backpack he must use for everything from shooting Tollah to beaming scientists to safety. Worse, he has just 60 minutes of real time to rescue as many scientists as possible and also beam himself back to safety. Freeman takes pain to make the game an engine for exciting emergent narrative. If Sudden runs out of energy completely, for instance, he still has one potential avenue of escape: if he can return to his beam-down location and be there in the 60th minute, an automated transporter beam will carry him to safety. One can imagine a desperate situation straight out of Star Wars or a Dominic Flandry story, the player racing back amid a hail of blaster fire as the clock runs down and Tollah dog his footsteps. Certainly one can imagine Freeman imagining it.

But living that drama requires a pretty substantial degree of commitment and a lively imagination on the part of the player, as one look at the rather ugly screenshot above will probably attest. Indeed, the DunjonQuest games feel always like a sort of hybrid of the digital and the tabletop RPG experience, with at least as much of the experience emerging from the player’s imagination as from the game itself. Perhaps it was a wise move, then, for Automated Simulations to target tabletop RPG players so aggressively in marketing DunjonQuest. After all, they were accustomed to having to roll up their sleeves a bit and exercise some imagination to come up with satisfying narratives. Automated Simulations advertised DunjonQuest extensively in TSR’s Dragon magazine, and, in a move that could hardly be more illustrative of the types of people they imagined enjoying DunjonQuest, even gave away for a time a strategic board game called Sticks and Stones with purchase of a DunjonQuest game.

In late 1980, Automated Simulations changed its game imprint to the less prosaic Epyx, adapting the tagline “Computer games thinkers play.” The DunjonQuest games just kept coming for another two years. Included amongst the later releases were a pair of expansion packs each for Temple of Apshai and Hellfire Warrior, the first examples of such I know amongst commercial computer games. The weirdest and most creative use of the DunjonQuest engine came with 1981’s Crush, Crumble, and Chomp!: The Great Movie Monster Game, in which the player got to take control of Godzilla (woops! Goshilla!) or another famous monster on an urban rampage. (For a detailed overview of the entire DunjonQuest series, which eventually amounted to a dozen games in total, see this article on Hardcore Gaming 101.)

Crush, Crumble, and Chomp! was, as it happened, the last work Freeman did for Epyx. At the West Coast Computer Faire of 1980, he had met a programmer named Anne Westfall; the two were soon dating. Westfall joined Epyx for a time, working as a programmer on some of the later DunjonQuest games. Both she and Freeman were, however, frustrated by Connelley’s disinterest in improving the DunjonQuest engine. Written in BASIC and originating on the now aging TRS-80 Model I, it had always been painfully slow, and was by now beginning to look dated indeed when ported to more modern and capable platforms. In addition, Freeman, a restless and creative designer, was growing tired with endless iterations on the DunjonQuest concept itself; he had had to battle hard even to go as far afield as Crush, Crumble, and Chomp!. At the end of 1981, Freeman and Westfall left Epyx to form the independent development house Free Fall Associates, about which I will have much more to say in the future. And after a couple of final DunjonQuest releases, Epyx morphed from “Computer Games Thinkers Play” into something very different, about which I will also have more to say in the future. Solid but never huge sellers even in their heyday, the DunjonQuest games by that time did not compare terribly well to a new generation of computer RPGs — about which, you guessed it, I will have more to say in the future.

If you’d like to sample the DunjonQuest experience, I can provide a sampler package with an Apple II disk image which includes Temple of Apshai, Rescue at Rigel, Morloc’s Tower, and Datestones of Ryn, as well as the manuals for each.

Next up: we begin to explore a work of unprecedented thematic depth that sets my literary-scholar proboscises all atingle.

Josh Lawrence

October 29, 2011 at 6:41 pm

Excellent article, Jimmy – I *loved* Crush, Crumble & Chomp back in the day (especially playing as the killer robot so you didn’t have to deal with pesky hunger) and I never realized it was a re-skin of the DunjonQuest engine, but that makes total sense.

One historical note you might want to add: the DunjonQuest games were, I think, one of the first (maybe the very first?) computer games to have the player consult “narrative” paragraphs in the manual at specific points, as a way of giving flavor text and clues that could not be squeezed onto the era’s floppy disks (Wasteland is probably the most famous later 80s example that did this). In DunjonQuest games, the text paragraphs were linked to the room number – they were room descriptions that attempted to fill in all that was missing in the game’s spare graphics, whereas Wasteland and some other games used the out-of-game paragraphs for actual story events (cutscenes) as well.

It is kind of another tie to the D&D tabletop experience, with the computer screen taking the part of the tabletop where player’s and enemy miniatures are arranged for tactical combat, (bare minimum of representation), and the textual descriptions of everything not represented on the tabletop are filled in by the DM reading the module’s room descriptions each time the players enter a new room.

Jimmy Maher

October 29, 2011 at 7:24 pm

Thanks!

I did cover that aspect of DunjonQuest in the earlier article on Temple of Apshai, which is why I didn’t bring it up again here. But you’re of course right that it feels very much drawn from D&D adventure modules.

Josh Lawrence

October 29, 2011 at 9:00 pm

Oh, apologies, I missed that earlier post! So much runs by in the IF Planet feed. :)

Sam Garret

November 17, 2011 at 9:07 pm

“Scott Adams, for instance, numbered each of his adventures, eventually ending up with a canonical dozen”

Are you including 13: Sorceror of Claymorgue amongst the canonical, it being arguably more famous than Golden Voyage? I couldn’t find a ref to what constituted his canon in the SA articles.

Jimmy Maher

November 18, 2011 at 3:42 pm

I know it’s a little bit arbitrary, but the canonical dozen are generally taken to be the first 12 that Adams authored or coauthored between 1978 and 1981: Adventureland to The Golden Voyage. These were all conceived and authored as pure text games, although graphics were later retrofitted into them (the SAGA series). They also were promoted together, all included in the same hint book, sold in some configurations as a set, and (perhaps most importantly) individually numbered from 1 to 12.

Sorcerer of Claymorgue, Return to Pirate Island (TI 99/4A only), and the Marvel Comics QuestProbe games were all designed later, and designed for graphics from the start. Nor were these games numbered in the same series as the first dozen. And there’s also of course the OtherVentures series by authors other than Adams, but often using Adams’s engine.

Mike Taylor

October 21, 2017 at 9:42 pm

“proboscises”?

Adele

January 19, 2018 at 11:32 pm

“Still, of the developers we’ve look at so far,”

Possibly you meant looked at?

Jimmy Maher

January 20, 2018 at 9:28 am

Thanks!

JudgeDeadd

March 23, 2018 at 3:07 pm

“a race of insectoid aliens known as the Toolah”

Actually the name is spelled Tollah (it’s even visible on the screenshot).

Jimmy Maher

March 24, 2018 at 9:57 pm

Thanks!

K. Garlow

January 2, 2019 at 1:12 pm

Typo: “DujonQuest” -> “DunjonQuest”

“in their heyday, the DujonQuest games…”

K. Garlow

January 2, 2019 at 1:15 pm

Also you still have 8 instances of “Toolah” instead of “Tollah.”

Jimmy Maher

January 3, 2019 at 8:49 am

Ouch. Thanks!

Will Moczarski

August 27, 2019 at 10:06 pm

in lieu of a denoument -> denouement

Jimmy Maher

September 1, 2019 at 9:44 am

Thanks!

Michael

October 25, 2019 at 10:19 pm

“the player got to take control of Godzilla (woops! Goshzilla!)”

I’m not even certain if this was a mistake, but in CCC, the monster’s name was “Goshilla.”

Jimmy Maher

October 28, 2019 at 3:32 pm

Thanks!

Ben

April 10, 2020 at 7:07 pm

designed for Temple of Aphsai -> Apshai

Jimmy Maher

April 12, 2020 at 7:42 am

Thanks!

Jeff Nyman

August 23, 2021 at 10:33 pm

Maybe I’m incorrect here, but I think some of these articles confuse “emergent gameplay” with the idea stated here in this article of “the experience emerging from the player’s imagination as from the game itself.”

Emergent gameplay is a very specific concept wherein players can create solutions or frame gameplay elements that the designer never intended. They emerge solely from the mechanics and rules rather than having been built in.

This article says: “Freeman takes pain to make the game an engine for exciting emergent narrative. If Sudden runs out of energy completely, for instance, he still has one potential avenue of escape: if he can return to his beam-down location and be there in the 60th minute, an automated transporter beam will carry him to safety.”

But that is not describing emergent narrative or emergent gameplay. It’s literally baked into the situation: IF you have no energy BUT you can reach beam-down point AND you are at that point specifically at the 60th minute THEN you will be beamed up.

Yes, you could argue this is a form of procedural narrative. But the emergent part comes from the player’s interactions with various gameplay systems; the narrative part is something else entirely. It’s understood in game design that narrative emergence are stories that, quite literally, emerge from the interaction between players and the systems that govern gameplay. They are generally more random, transient, and ephemeral and generally only ever exist for one person at one moment in time. That’s the very opposite of what’s being described with “Rescue at Rigel.”

Consider a better example in, say, “Assassin’s Creed: Origins.” You can be investigating who is embalming corpses in a way that violates custom and law. But you can accidentally scare some people in the nearby area and what might happen is that in running, they knock over some fire lamps. This can (1) kill one of the people you are trying to question, (2) burn up the evidence you are looking for (3) both of those things. Yet — you can continue, up to a point. Yet perhaps not fully. Thus, on that quest chain, you may help some of the people but never catch the culprit. Or you may catch the wrong culprit. Or you may just decide, “Well, this was a waste of time” and not even bother helping the people you could have helped, however limited. Even if none of THAT happens, it turns out you can accidentally desecrate some of the corpses yourself such that your investigation is short-circuited from the get-go.

In game design you learn that truly emergent narrative is really just a living outline that can be rearranged on the fly, in the moment. It’s a sequence of vaguely or not-so-vaguely related events. And all of this is a commingling of gameplay systems and characterization, where one reinforces the other.

The best game design courses will teach you this mantra: if something is completely authored, then it isn’t emergent.

Busca

March 3, 2022 at 9:06 am

“TSR’s one game / many products approach to marketing and its zeal for cataloging surfaces even amongst early computer-game developers that were not trying to adapt the D&D rules to the digital world.” -> seems there is at least a word missing here?

BTW, at least for me it would be fine to delete comments which only post typo-style corrections as they kind of interrupt the “flow” when going through the (other) comments (which refer to content) and – I feel – do not add anything for your readers. Not sure if you’ve addressed this already elsewhere in the >10 years of this great blog I am only starting to discover in more detail. Just a suggestion, of course – feel free to delete this one, too.

Jimmy Maher

March 4, 2022 at 8:49 am

As intended, thanks.

I do understand the arguments for deleting “mere” typo corrections, but the idea has never quite set right with me. The archivist in me feels a need to preserve them for the record, while I also feel it’s appropriate to acknowledge somehow the contributions of the folks who help me to make these articles better. And then there are often fuzzy borders between typo corrections, the pointing out of errors of fact, stylistic suggestions, and push backs against conclusions or opinions I express (whether the last two lead to actual changes in the article or not). Many comments include all three. I’m not sure I want to become an arbiter of which comments are worth preserving and which are not. And I certainly wouldn’t want to appear to be flushing my mistakes — which, as the comment record documents, tend to be legion — down the memory hole. I think it’s better to be completely open and transparent about what was changed.

Finally, these comments and their acknowledgements serve the practical purpose of pointing out that even small, seemingly pedantic corrections are welcomed by me, and thus encourage people to *keep on* helping me to make these articles better.