If you rushed out excitedly to buy an Amiga in the early days because it looked about to revolutionize gaming, you could be excused if you felt just a little bit disappointed and underwhelmed as the platform neared its first anniversary in shops. There was a reasonable amount of entertainment software available — much of it from the Amiga’s staunchest supporter, Electronic Arts — but nothing that felt quite as groundbreaking as EA’s early rhetoric about the Amiga would imply. Even the games from EA were mostly ports of popular 8-bit titles, modestly enhanced but hardly transformed. More disappointing in their way were the smattering of original titles. Games like Arcticfox and Marble Madness had their charms, but there was nothing conceptually new about them. Degrade the graphics and sound just slightly and they too could easily pass for 8-bit games. But then, timed to neatly correspond with that one-year anniversary, along came Defender of the Crown, the Amiga’s first blockbuster and to this day the game many old-timers think of first when you mention the platform.

Digital gaming in general was a medium in flux in the mid-1980s, still trying to understand what it was and where it fit on the cultural landscape. The preferred metaphor for pundits and developers alike immediately before the Amiga era was the book; the bookware movement brought with it Interactive Fiction, Electronic Novels, Living Literature, and many other forthrightly literary branded appellations. Yet in the big picture bookware had proved to be something of a commercial dud. Defender of the Crown gave the world a new metaphorical frame, one that seemed much better suited to the spectacular audiovisual capabilities of the Amiga. Cinemaware, the company that made it, had done just what their name would imply: replaced the interactive book with the interactive movie. In the process, they blew the doors of possibility wide open. In its way Defender of the Crown was as revolutionary as the Amiga itself — or, if you like, it was the long-awaited proof of concept for the Amiga as a revolutionary technology for gaming. All this, and it wasn’t even a very good game.

The Cinemaware story begins with Bob Jacob, a serial entrepreneur and lifelong movie buff who fulfilled a dream in 1982 by selling his business in Chicago and moving along with his wife Phyllis to Los Angeles, cradle of Hollywood. With time to kill while he figured out his next move, he became fascinated with another, newer form of media: arcade and computer games. He was soon immersing himself in the thriving Southern California hacker scene. Entrepreneur that he was, he smelled opportunity there. Most of the programmers writing games around him were “not very articulate” and clueless about business. Jacob realized that he could become a go-between, a bridge between hackers and publishers who assured that the former didn’t get ripped off and that the latter had ready access to talent. He could become, in other words, a classic Hollywood agent transplanted to the brave new world of software. Jacob did indeed became a modest behind-the-scenes player over the next couple of years, brokering deals with the big players like Epyx, Activision, Spinnaker, and Mindscape for individuals and small development houses like Ultrasoft, Synergistic, Interactive Arts, and Sculptured Software. And then came the day when he saw the Amiga for the first time.

Jacob had gotten a call from a developer called Island Graphics, who had been contracted by Commodore to write a paint program to be available on Day One for the Amiga. But the two companies had had a falling out. Now Island wanted Jacob to see if he could place the project with another publisher. This he succeeded in doing, signing Island with a new would-be Amiga publisher called Aegis; Island’s program would be released as Aegis Images. (Commodore would commission R.J. Mical to write an alternate paint program in-house; it hit the shelves under Commodore’s own imprint as GraphiCraft.) Much more important to Jacob’s future, however, was his visit to Island’s tiny office and his first glimpse of the prototype Amigas they had there. Like Trip Hawkins and a handful of others, Jacob immediately understood what the Amiga could mean for the future of gaming. He understood so well, in fact, that he made a life-changing decision. He decided he wanted to be more than just an agent. Rather than ride shotgun for the revolution, he wanted to drive it. He therefore wound down his little agency practice in favor of spearheading a new gaming concept he dubbed “Cinemaware.”

Jacob has recounted on a number of occasions the deductions that led him to the Cinemaware concept. A complete Amiga system was projected to cost in the neighborhood of $2000. Few of the teenagers who currently dominated amongst gamers could be expected to have parents indulgent enough to spend that kind of money on them. Jacob therefore expected the demographic that purchased Amigas to skew upward in age — toward people like him, a comfortably well-off professional in his mid-thirties. And people like him would not only want, as EA would soon be putting it, “the visual and aural quality our sophisticated eyes and ears demand,” but also more varied and nuanced fictional experiences. They would, in other words, like to get beyond Dungeons and Dragons, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and Star Trek as the sum total of their games’ cultural antecedents. At the same time, though, their preference for more varied and interesting ludic fictions didn’t necessarily imply that they wanted games that were all that demanding on their time or even their brainpower. This is the point where Jacob diverged radically from Infocom, the most prominent extant purveyor of sophisticated interactive fictions. The very first computer game that Jacob had ever bought had been Infocom’s Deadline. He hadn’t been all that taken with the experience even at the time. Now, what with its parser-based interface and all the typing that that entailed, its complete lack of audiovisual flash, its extensive manual and evidence reports that the player was expected to read before even putting the disk in the drive, and the huge demands it placed on the player hoping to actually solve its case, it served as a veritable model for what Jacob didn’t want his games to be. Other forms of entertainment favored by busy adults weren’t so demanding. Quite the opposite, in fact. His conception of adult gaming would have it be as easy-going and accessible as television. Thus one might characterize Jacob’s vision as essentially Trip Hawkins’s old dictum of “simple, hot, and deep,” albeit with a bit more emphasis on the “hot” and a bit less on the “deep.” The next important question was where to find those more varied and nuanced fictional experiences. For a movie buff living on the very doorstep of Tinsel Town, the answer must have all but announced itself of its own accord.

Bookware aside, the game industry had to some extent been aping the older, more established art form of film for a while already. The first attempt that I’m aware of to portray a computer game as an interactive movie came with Sierra’s 1982 text-adventure epic Time Zone, the advertising for which was drawn as a movie poster, complete with “Starring: You,” “Admission: $99.95,” and a rating of “UA” for “Ultimate Adventure.” It was also the first game that I’m aware of to give a credit for “Producer” and “Executive Producer.” Once adopted and popularized by Electronic Arts the following year, such movie-making terminology spread quickly all over the game industry. Now Bob Jacob was about to drive the association home with a jackhammer.

Each Cinemaware game would be an interactive version of some genre of movies, drawn from the rich Hollywood past that Jacob knew so well. If nothing else, Hollywood provided the perfect remedy for writer’s block: “Creatively it was great because we had all kinds of genres of movies to shoot for.” Many of the movie genres in which Cinemaware would work felt long-since played-out creatively by the mid-1980s, but most gaming fictions were still so crude by comparison with even the most hackneyed Hollywood productions that it really didn’t matter: “I was smart enough and cynical enough to realize that all we had to do was reach the level of copycat, and we’d be considered a breakthrough.”

Cynicism notwithstanding, the real, obvious love that Jacob and a number of his eventual collaborators had for the movies they so self-consciously evoked would always remain one of the purest, most appealing things about Cinemaware. Their manuals, scant and often almost unnecessary as they would be, would always make room for an affectionate retrospective on each game’s celluloid inspirations. At the same time, though, we should understand something else about the person Jacob was and is. He’s not an idealist or an artist, and certainly not someone who spends a lot of time fretting over games in terms of anything other than commercial entertainment. He’s someone for whom phrases like “mass-market appeal” — and such phrases tend to come up frequently in his discourse — hold nary a hint of irony or condescension. Even his love of movies, genuine as it may be, reflects his orientation toward mainstream entertainment. You’ll not find him waiting for the latest Criterion Collection release of Bergman or Truffaut. No, he favors big popcorn flicks with, well, mass-market appeal. Like so much else about Jacob, this sensibility would be reflected in Cinemaware.

Financing for a new developer wasn’t an easy thing to secure in the uncertain industry of 1985. Perhaps in response, Jacob initially conceived of his venture as a very minimalist operation, employing only himself and his wife Phyllis on a full-time basis. The other founding member of the inner circle was Kellyn Beeck, a friend, software acquisitions manager at Epyx, fellow movie buff, and frustrated game designer. The plan was to give him a chance to exorcise the latter demon with Cinemaware. Often working from Jacob’s initial inspiration, he would provide outside developers with design briefs for Cinemaware games, written in greater or lesser detail depending on the creativity and competency of said developers. When the games were finished, Jacob would pass them on to Mindscape for publication as part of the Cinemaware line. One might say that it wasn’t conceptually all that far removed from the sort of facilitation Jacob had been doing for a couple of years already as a software agent. It would keep the non-technical Jacob well-removed from the uninteresting (to him) nuts and bolts of software development. Jacob initially called his company Master Designer Software, reflecting both an attempt to “appeal to the ego of game designers” and a hope that, should the Cinemaware stuff turn out well, he might eventually launch other themed lines. Cinemaware would, however, become such a strong brand in its own right in the next year or two that Jacob would end up making it the name of his company. I’ll just call Jacob’s operation “Cinemaware” from now on, as that’s the popular name everyone would quickly come to know it under even well before the official name change.

After nearly a year of preparation, Jacob pulled the trigger on Cinemaware at last in January of 1986, when in a matter of a few days he legally formed his new company, signed a distribution contract with Mindscape, and signed contracts with outsiders to develop the first four Cinemaware games, to be delivered by October 15, 1986 — just in time for Christmas. Two quite detailed design briefs went to Sculptured Software of Salt Lake City, a programming house that had made a name for themselves as a porter of games between platforms. Of Sculptured’s Cinemaware projects, Defender of the Crown, the title about which Jacob and Beeck were most excited, was inspired by costume epics of yesteryear featuring legendary heroes like Ivanhoe and Robin Hood, while SDI was to be a game involving Ronald Reagan’s favorite defense program and drawing its more tenuous cinematic inspiration from science-fiction classics ranging from the Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s to the recent blockbuster Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. The other two games went to proven lone-wolf designer/programmers, last of a slowly dying breed, and were outlined in much broader strokes. King of Chicago, given to a programmer named Doug Sharp who had earlier written a game called ChipWits, an interesting spiritual successor to Silas Warner’s classic Robot War, was to be an homage to gangster movies. And Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon was given to one Bill Williams, who had earlier written such Atari 8-bit hits as Necromancer and Alley Cat and had just finished the first commercial game ever released for the Amiga, Mind Walker. His game would be an homage to Hollywood’s various takes on the Arabian Nights. Excited though he was by the Amiga, Jacob hedged his bets on his platforms just as he did on his developers, planning to get at least one title onto every antagonist in the 68000 Wars before 1986 was out. Only Defender of the Crown and Sinbad were to be developed and released first on the Amiga; King of Chicago would be written on the Macintosh, SDI on the Atari ST. If all went well, ports could follow.

All of this first wave of Cinemaware games as well as the ones that would follow will get their greater or lesser due around here in articles to come. Today, though, I want to concentrate on the most historically important if certainly not the best of Cinemaware’s works, Defender of the Crown.

Defender of the Crown, then, takes place in a version of medieval England that owes far more to cinema than it does to history. As in romantic depictions of Merry Olde England dating back at least to Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, the stolid English Saxons are the heroes here, the effete French Normans — despite being the historical victors in the struggle for control of England — the villains. Thus you play a brave Saxon lord struggling against his Norman oppressors. Defender of the Crown really doesn’t make a whole lot of sense as history, fiction, or legend. A number of its characters are drawn from Ivanhoe, which might lead one to conclude that it’s meant to be a sequel to that book, taking place after Richard I’s death has thrown his kingdom into turmoil once again. But if that’s the case then why is Reginald Front-de-Boeuf, who was killed in Ivanhoe, running around alive and well again? Should you win Defender of the Crown, you’ll be creating what amounts to an alternate history in which the Saxons throw off the Norman yoke and regain control of England. Suffice to say that the only history that Defender of the Crown is really interested in is the history of Hollywood. What it wants to evoke is not the England of myth or reality, but the England of the movies so lovingly described in its manual. It has no idea where it stands in relation to Ivanhoe or much of anything else beyond the confines of a Hollywood sound stage, nor does it care. Given that, why should we? So, let’s agree to just go with it.

Defender of the Crown is essentially Risk played on a map of England. The other players in the game include three of the hated Normans and two other Saxon lords, who generally try to avoid attacking their ethnic fellows unless space starts getting really tight. Your goal is of course to wipe the Normans from the map and make of England a Saxon kingdom again. Woven into the simple Risk-like strategy game are a handful of action-oriented minigames that can be triggered by your own actions or those of the other lords: a grand jousting tournament, a midnight raid on an enemy castle, a full-on siege complete with a catapult that you use to knock down a beleaguered castle’s walls. In keeping with Jacob’s vision of Cinemaware games as engaging but light entertainments, a full game usually takes well under an hour to play, and there is no provision for saving or restoring.

From the beginning, it was Jacob’s intention to really pull out all the stops for Defender of the Crown in particular amongst his launch titles, to make of it an audiovisual showcase the likes of which had never been seen before. Shortly after signing Sculptured Software to do the programming, he therefore signed Jim Sachs to work with them, giving him a title familiar to Hollywood but new to the world of games: Art Director.

A Jim Sachs self-portrait, one of his early Amiga pictures that won him the job of Art Director for Defender of the Crown.

A self-taught artist from childhood and a programmer since he’d purchased a Commodore 64 just a few years before, Sachs had made quite a name for himself in quite a short time in Commodore circles. He’d written and released a game of his own for the Commodore 64, Saucer Attack, that mixed spectacular graphics with questionable gameplay (an accusation soon to be leveled against Defender of the Crown as well). He’d then spent a year working on another game, to be called Time Crystal, that never got beyond a jawdropping demo that made the rounds of Commodore 64 BBSs for years. He’d been able to use this demo and Saucer Attack to convince Commodore to give him developer’s status for the Amiga, allowing him access to pre-release hardware. Sachs’s lovely early pictures were amongst the first to be widely distributed amongst Amiga users, making him the most well-known of the Amiga’s early hacker artists prior to Eric Graham flooring everyone with his Juggler animation in mid-1986. Indeed, Sachs was quite possibly the best Amiga painter in the world when Jacob signed him up to do Defender of the Crown — Andy Warhol included. He would become the most important single individual to work on the game. If it was unusual for an artist to become the key figure behind a game, that itself was an illustration of what made Cinemaware — and particularly Defender of the Crown — so different from what had come before. As he himself was always quick to point out, Sachs by no means personally drew every single one of the many lush scenes that make up the game. At least seven others contributed art, an absolutely huge number by the standards of the time, and another sign of what made Defender of the Crown so different from everything that had come before. It is fair to say, however, that Sachs’s virtual brush swept over every single one of the game’s scenes, tweaking a shadow here, harmonizing differing styles there. His title of Art Director was very well-earned.

This knight, first distributed by Jim Sachs as a standalone picture, would find his way into Defender of the Crown almost unaltered.

By June of 1986 Sachs and company had provided Sculptured Software with a big pile of mouth-watering art, but Sculptured had yet to demonstrate to Jacob even the smallest piece of a game incorporating any of it. Growing concerned, Jacob flew out to Salt Lake City to check on their progress. What he found was a disaster: “Those guys were like nowhere. Literally nowhere.” Their other game for Cinemaware, SDI, was relatively speaking further along, but also far behind schedule. It seemed that this new generation of 68000-based computers had proved to be more than Sculptured had bargained for.

Desperate to meet his deadline with Mindscape, Jacob took the first steps toward his eventual abandonment of his original concept of Cinemaware as little more than a creative director and broker between developer and publisher. He hired his first actual employee beyond himself and Phyllis, a fellow named John Cutter who had just been laid off following Activision’s acquisition of his previous employer Gamestar, a specialist in sports games. Cutter, more technical and more analytical than Jacob, would become his right-hand man and organizer-in-chief for Cinemaware’s many projects to come. His first task was to remove Sculptured Software entirely from Defender of the Crown; S.D.I. they were allowed to keep, but from now on they’d work on it under close supervision from Cutter. Realizing he needed someone who knew the Amiga intimately to have a prayer of completing Defender of the Crown by October 15, Jacob called up none other than R.J. Mical, developer of Intuition and GraphiCraft, and made him an offer: $26,000 if he could take Sachs’s pile of art and Jacob and Beeck’s design, plus a bunch of music Jacob had commissioned from a composer named Jim Cuomo, and turn it all into a finished game within three months. Mical simply said — according to Jacob — “I’m your man.”

He got it done, even if it did nearly kill him. Mical insists to this day that Jacob wasn’t straight with him about the project, that the amount of work it ended up demanding of him was far greater than what he had been led to expect when he agreed to do the job. He was left so unhappy by his rushed final product that he purged his own name from the in-game credits. Sachs also is left with what he calls a “bitter taste,” feeling Jacob ended up demanding far, far more work from him than was really fair for the money he was paid. Many extra graphical flourishes and entire additional scenes that Mical simply didn’t have time or space to incorporate into the finished product were left on the cutting-room floor. Countless 20-hour days put in by Sachs and his artists thus went to infuriating waste in the name of meeting an arbitrary deadline. Sachs claims that five man-weeks work worth of graphics were thrown out for the jousting scenes alone. Neither Sachs nor Mical would ever work with Cinemaware again.

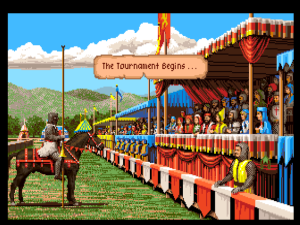

Jousting, otherwise known as occasionally knocking the other guy off his horse for no discernible reason but mostly getting unhorsed yourself.

Many gameplay elements were also cut, while even much of what did make it in has an unfinished feel about it. Defender of the Crown manages the neat trick of being both too hard and too easy. What happens on the screen in the various action minigames feels peculiarly disconnected from what you actually do with the mouse. I’m not sure anyone has ever entirely figured out how the jousting or swordfighting games are even supposed to work; random mouse twiddling and praying would seem to be the only viable tactics. And yet the Risk-style strategic game is almost absurdly easy. Most players win it — and thus Defender of the Crown as a whole — on their second if not their first try, and then never lose again.

Given this, it would be very easy to dismiss Defender of the Crown entirely. And indeed, plenty of critics have done just that, whilst often tossing the rest of Cinemaware’s considerable catalog into the trash can of history alongside it. But, as the length of this article would imply, I’m not quite willing to do that. I recognize that Defender of the Crown isn’t really up to much as a piece of game design, yet even today that doesn’t seem to matter quite as much as it ought to. Simplistic and kind of broken as it is, it’s still a more entertaining experience today than it ought to be — certainly enough so to be worth a play or two. And back in 1986… well, I united England under the Saxon banner a ridiculous number of times as a kid, long after doing so became rote. In thinking about Defender of the Crown‘s appeal, I’ve come to see it as representing an important shift not just in the way that games are made but also in the way that we experience them. To explain what I mean I need to get a bit theoretical with you, just for a moment.

Whilst indulging in a bit of theory in an earlier article, I broke down a game into three component parts: its system of rules and mechanics, its “surface” or user interface, and its fictional context. I want to set aside the middle entry in that trio and just think about rules and context today. As I also wrote in that earlier article, the rise in earnest of what I call “experiential games” from the 1950s onward is marked by an increased interest in the latter in comparison to the former, as games became coherent fictional experiences to be lived rather than mere abstract systems to be manipulated in pursuit of a favorable outcome. I see Defender of the Crown and the other Cinemaware games as the logical endpoint of that tendency. In designing the game, Bob Jacob and Kellyn Beeck started not with a mechanical concept — grand strategy, text adventure, arcade action, etc. — but with a fictional context: a recreation of those swashbuckling Hollywood epics of yore. That the mechanical system they came up with to underlie that fiction — a simplified game of Risk peppered by equally simplistic action games — is loaded with imperfections is too bad but also almost ancillary to Defender of the Crown the experience. The mechanics do the job just well enough to make themselves irrelevant. No one comes to Defender of the Crown to play a great strategy game. They come to immerse themselves in the Merry Olde England of bygone Hollywood.

For many years now there have been voices stridently opposed to the emphasis a game like Defender of the Crown places on its fictional context, with the accompanying emphasis on foreground aesthetics necessary to bring that context to life. Chris Crawford, for instance, dismisses not just this game but Cinemaware as a whole in one paragraph in On Game Design as “lots of pretty pictures and animated sequences” coupled to “weak” gameplay. Gameplay is king, we’re told, and graphics and music and all the rest don’t — or shouldn’t — matter a whit. Crawford all but critically ranks games based entirely on what he calls their “process intensity”: their ratio of dynamic, interactive code — i.e., gameplay — to static art, sound, music, even text. If one accepts this point of view in whole or in part, as many of the more prominent voices in game design and criticism tend to do, it does indeed become very easy to dismiss the entire oeuvre of Cinemaware as a fundamentally flawed concept and, worse, a dangerous one, a harbinger of further design degradations to come.

Speaking here as someone with an unusual tolerance for ugly graphics — how else could I have written for years now about all those ugly 8-bit games? — I find that point of view needlessly reductive and rather unfair. Leaving aside that beauty for its own sake, whether found in a game or in an art museum, is hardly worthy of our scorn, the reality is that very few modern games are strictly about their mechanics. Many have joined Defender of the Crown as embodied fictional experiences. This is the main reason that many people play them today. If beautiful graphics help us to feel embodied in a ludic world, bully for them. I’d argue that the rich graphics in Defender of the Crown carry much the same water as the rich prose in, say, Mindwheel or Trinity. Personally — and I understand that mileages vary here — I’m more interested in becoming someone else or experiencing — there’s that word again! — something new to me for a while than I am in puzzles, strategy, or reflex responses in the abstract. I’d venture to guess that most gamers are similar. In some sense modern games have transcended games — i.e., a system of rules and mechanics — as we used to know them. Commercial and kind of crass as it sometimes is, we can see Defender of the Crown straining toward becoming an embodied, interactive, moving, beautiful, fictional experience rather than being just the really bad take on Risk it unquestionably also is.

A fetching lass gives you the old come-hither stare. Those partial to redheads or brunettes also have options.

A good illustration of Defender of the Crown‘s appeal as an experiential fiction as well as perhaps a bit of that aforementioned crassness is provided by the game’s much-discussed romantic angle. No Hollywood epic being complete without a love interest for the dashing hero, you’ll likely at some point during your personal epic get the opportunity to rescue a Saxon damsel in distress from the clutches of a dastardly Norman. We all know what’s bound to happen next: “During the weeks that follow, gratitude turns to love. Then, late one night…”

Consummating the affair. Those shadows around waist-level are… unfortunate. I don’t think they’re actually supposed to look like what they look like, although they do give a new perspective to the name of “Geoffrey Longsword.”

After the affair is consummated, your new gal accompanies you through the rest of the game. It’s important to note here that she has no effect one way or the other on your actual success in reconquering England, and that rescuing her is actually one of the more difficult things to do in Defender of the Crown, as it requires that you engage with the pretty terrible swordfighting game; I can only pull it off if I pick as my character Geoffrey Longsword, appropriately enough the hero with “Strong” swordfighting skills. Yet your game — your story — somehow feels incomplete if you don’t manage it. What good is a hero without a damsel to walk off into the sunset with him? There are several different versions of the virgin (sorry!) that show up, just to add a bit of replay value for the lovelorn.

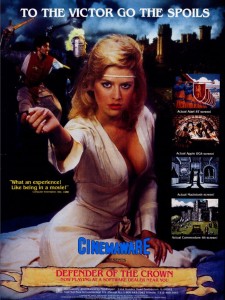

As I’ve written earlier, 1986 was something of a banner year for sex in videogames. The love scene in Defender of the Crown, being much more, um, graphic than the others, attracted particular attention. Many a youngster over the years to come would have his dreams delightfully haunted by those damsels. Shortly after the game’s release, Amazing Computing published an unconfirmed report from an “insider” that the love scene was originally intended to be interactive, requiring “certain mouse actions to coax the fair woman, who reacted accordingly. After consulting with game designers and project management, the programmer supposedly destroyed all copies of the source code to that scene.” Take that with what grains of salt you will. At any rate, a sultry love interest would soon become a staple of Cinemaware games, for the very good reason that the customers loved them. And anyway, Jacob himself, as he later admitted in a revelation bordering on Too Much Information, “always liked chesty women.” It was all horribly sexist, of course, something Amazing Computing pointed out by declaring Defender of the Crown the “most anti-woman game of the year.” On the other hand, it really wasn’t any more sexist than its cinematic inspirations, so I suppose it’s fair enough when taken in the spirit of homage.

Cinemaware wasn’t shy about highlighting one of Defender of the Crown‘s core appeals. Did someone mention sexism?

The buzz about Defender of the Crown started inside Amiga circles even before the game was done. An early build was demonstrated publicly for the first time at the Los Angeles Commodore Show in September of 1986; it attracted a huge, rapt crowd. Released right on schedule that November through Mindscape, Defender of the Crown caused a sensation. Amiga owners treated it as something like a prophecy fulfilled; this was the game they’d all known the Amiga was capable of, the one they’d been waiting for, tangible proof of their chosen platform’s superiority over all others. And it became an object of lust — literally, when the gorgeously rendered Saxon maidens showed up — for those who weren’t lucky enough to own Commodore’s wunderkind. You could spend lots of time talking about all of the Amiga’s revolutionary capabilities — or you could just pop Defender of the Crown in the drive, sit back, and watch the jaws drop. The game sold 20,000 copies before the end of 1986 alone, astounding numbers considering that the total pool of Amiga owners at that point probably didn’t number much more than 100,000. I feel pretty confident in saying that just about every one of those 80,000 or so Amiga owners who didn’t buy the game right away probably had a pirated copy soon enough. It would go on to sell 250,000 copies, the “gift that kept on giving” for Jacob and Cinemaware for years to come. While later Cinemaware games would be almost as beautiful and usually much better designed — not to mention having the virtue of actually being finished — no other would come close to matching Defender of the Crown‘s sales numbers or its public impact.

Laying siege to a castle. The Greek fire lying to the left of the catapult can’t be used. It was cut from the game but not the graphics, only to be added back in in later ports.

Cinemaware ported Defender of the Crown to a plethora of other platforms over the next couple of years. Ironically, virtually all of the ports were much better game games than the Amiga version, fixing the minigames to make them comprehensible and reasonably entertaining and tightening up the design to make it at least somewhat more difficult to sleepwalk to victory. In a sense, it was Atari ST users who got the last laugh. That, anyway, is the version that some aficionados name as the best overall: the graphics and sound aren’t quite as good, but the game behind them has been reworked with considerable aplomb. Even so, it remained and remains the Amiga version that most people find most alluring. Without those beautiful graphics, there just doesn’t seem to be all that much point to Defender of the Crown. Does this make it a gorgeous atmospheric experience that transcends its game mechanics or just a broken, shallow game gussied up with lots of pretty pictures? Perhaps it’s both, or neither. Artistic truth is always in the eye of the beholder. But one thing is clear: we’ll be having these sorts of discussions a lot as we look at games to come. That’s the real legacy of Defender of the Crown — for better or for worse.

(Sources: On the Edge by Brian Bagnall; Computer Gaming World of January/February 1985, March 1987 and August/September 1987; Amazing Computing #1.9, February 1987, April 1987, and July 1987; Commodore Magazine of October 1987 and November 1988; AmigaWorld of November/December 1986. Jim Sachs has been interviewed in more recent years by Kamil Niescioruk and The Personal Computer Museum. Matt Barton and Tristan Donovan have each interviewed Bob Jacob for Gamasutra.

Defender of the Crown is available for purchase for Windows and Mac from GOG.com and in the Apple Store for iOSfor those of you wanting to visit Merry Olde England for yourselves. All emulate the historically definitive if somewhat broken Amiga version, featuring the original Amiga graphics and sound.)

Matthew

April 16, 2015 at 4:53 pm

Heh. So I was reading this and thinking “hey, I don’t remember it being that bad a game”. But I played the PC version, and then I got to the end where you mention the ports being much better. Flip side is the PC version’s graphics were not especially great even for the PC (I can’t remember if it was EGA or VGA, anyone?). Now, the Cinemaware game I really did think had terrible gameplay was the Three Stooges. Felt like they were concentrating so much on the “Cinema” part that they didn’t even bother with the “Game” part (Again, PC version, Amiga may have been better, etc).

Lisa H.

April 16, 2015 at 8:53 pm

I haven’t played it, but if the graphics resembled those above I would think they’d be EGA?

Jimmy Maher

April 17, 2015 at 5:12 am

Saying they “resemble” the Amiga graphics is perhaps being too kind: http://www.mobygames.com/game/dos/defender-of-the-crown/screenshots.

Those are obviously CGA. I don’t know if Defender of the Crown ever supported EGA. Even if it did, you couldn’t really duplicate the Amiga graphics. EGA allowed 16 onscreen colors from a palette of 64, the Amiga 32 onscreen from a palette of 4096. (There were lots of fairly simple tricks to get a lot more colors than that onscreen on the Amiga, but I don’t think Defender of the Crown uses them.) So, you’d need VGA to get there.

Doug Orleans

April 17, 2015 at 6:01 am

Breaking: you can get 1024 colors on CGA now!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHXx3orN35Y

http://8088mph.blogspot.com/2015/04/cga-in-1024-colors-new-mode-illustrated.html

Matthew

April 17, 2015 at 8:11 pm

Yep, no way you could get screenshots like the above with EGA. Remember, it’s not just that EGA only gave 16 colors, they were completely unchangeable, and given that CGA/EGA monitors were digital, I’d say impossible to hack around (the CGA hack that Doug posted, while super amazing, used a Composite monitor that was somewhat more flexible hardware wise).

That said, this prompted me to google and there definitely was an EGA version of Defender, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccLqRMlpYdM for a playthrough.

Waiting patiently for this blog to get to the point in a few more years when VGA+Soundblaster+Roland comes along and the PC finally stops being an embarrassment gaming wise.

Jim Leonard

May 7, 2015 at 11:57 am

There was an EGA/Tandy port with substantially better graphics than the screenshots you linked to, but it is uncommon as it was released outside of the United States. The graphics are much closer to the Amiga in that version, but the limited number of colors can’t quite do the game the same justice.

Alex

April 18, 2015 at 4:11 am

Ah, nobody loved The Three Stooges. Just to give some perspective to the platform debates sparked by this article: Imagine the uncharacteristic patience of a child waiting for it to load on a 256k PC Junior in glorious washed out CGA graphics. Even then, the presentation carried a lot for someone used to the NES, as well as the great Defender of the Crown gag at the beginning.

Speaking of perspective, I’ll assume the NES version is going to (charitably) go unmentioned.

Steve Taylor

February 14, 2022 at 10:19 pm

> Speaking of perspective, I’ll assume the NES version is going to (charitably) go unmentioned.

Challenge accepted! I was working at Beam Software/Melbourne House at the time, and the port was done by a friend of mine. He was a salaried employee, but this particular game was done as a seperate contract. I think the idea was that our boss (correctly) decided that my friend was a particularly productive programmer, and that by dangling a carrot before him he could get two carrots worth of work.

As for the game, I only wrote one game on the Nintendo (the dull and disappointing Airwolf. I’m sorry) but I think I recall that like the Spectrum it divided the screen into character cells and while it allowed high res graphics in those cells, it had strict limits on how many colours were possible, and this made reproducing beautiful Amiga graphics a bit of a challenge (or am I getting mixed up with the Spectrum – it was a terrifyingly long time ago!)

Pedro Timóteo

April 16, 2015 at 5:16 pm

Great as always. :)

Just one thing: you mention that rescuing a damsel and getting married didn’t actually change anything in the game, but I seem to remember (maybe not on the Amiga version, though; I never owned one, unfortunately, but I did play a lot of the PC port) that, when you did so, the girl’s father (one of the other Saxon lords) decided to “retire” and you got all of his lands for free. Then again, it’s been a long time.

Unrelated to this: are you planning a post about Jeff Minter and his games? You once kind of implied you would write one…

Jimmy Maher

April 16, 2015 at 7:11 pm

It might very well have some concrete effect in other versions. I do seem to remember some speculation that having a wife might help you fight better in the strategic game. But the strategic game is so easy that it’s kind of hard to judge…

I don’t think I’ll be writing on Minter. I’m already kind of past his first heyday, and his style of game just isn’t one that I’m all that interested in or qualified to write about. Sorry!

Pedro Timóteo

April 17, 2015 at 8:51 am

Pity about Minter (I’m a big fan, and incidentally only “discovered” him in the 2000s, not in the 80s), but understandable, we can’t have be equally interested in everything, and I love most of what you do write about (not only computers and games, but the history itself).

Janne Nordström

March 20, 2019 at 2:45 am

Just for posteritys sake: if you rescue a lady, you’ll get his fathers kingdom. One of the saxon allied kingdoms lands will be annexed by you. No armies though. This is what happened in the Commodore 64 version.

The objective of joust was to hit the opponents shield (aim at shield and click when you’re close enough). If you hit his horse, the poor beast would collapse and you would be disqualified. Tournaments were best way to conquer a lot of land quickly, because you could joust for land and do so twice per tournament. You’re also not limited by geography.

As for swordfights, the winning strategy was to block until your opponent stopped striking at you and poke a quick hit in. Do that enough times and you whittle his health down. Unfortunately you only need to do it once as robbing castles for gold is a poor strategy.

Did you know, you could click on Sherwood forest before a castle assault and have Robin Hood help you out a little?

matt w

April 16, 2015 at 5:34 pm

When I first scrolled past that advertisement on Planet-IF I was like “Why is Jimmy reviewing Evony?”

Typo patrol: you have “20,0000” with an extra 0 after the comma.

Jimmy Maher

April 16, 2015 at 7:09 pm

Just one more way that Cinemaware was prescient. Thanks!

iPadCary

April 16, 2015 at 6:44 pm

Definately a historic fave.

On iPad now, if anyone’s interested!

Jimmy Maher

April 16, 2015 at 7:22 pm

Thanks. I forgotten the mobile versions. Note added.

Mats Pehrson

April 16, 2015 at 7:32 pm

The Amiga version was updated with all the missing features in the CDTV-version, which is in my opinion the best version overall.

Also, on the CD32 was released Defender of the Crown II; more or less the same game but with some added gameplay (for instance, the goal is to collect a ransom for king Richard).

Lisa H.

April 16, 2015 at 8:54 pm

Jousting, otherwise known as occasionally knocking the other guy off his horse for no discernible reason but mostly getting unhorsed yourself. … random mouse twiddling and praying would seem to be the only viable tactics

LOL. I haven’t played this particular game (though I think I have vague memories of seeing it as demo software on an Amiga in a software/computer store way back when) but I feel much the same way about the jousting in Sierra’s Conquests of Camelot. Although that does at least tell you what keypresses do what motions (ditto the somewhat complicated swordfighting, which uses the whole numpad), it’s just that figuring out what the Right Thing to do in response to any particular movement from the opponent was always obscure to me. When I won, I had no idea how I’d done it, and mostly I just lost. Rather frustrating.

Andrew McCarthy

April 16, 2015 at 10:37 pm

The jousting in Conquests of Camelot is ridiculously hard. But the swordfight does have a (rather un-intuitive ludically but very realistic) trick to it.

Namely, spend the first part of the fight on the defensive, attacking as little as possible. Your opponent will tire himself out attacking you, allowing you to press your advantage as the fight progresses.

Lisa H.

April 17, 2015 at 7:56 am

Yeah, fighting the Saracen at the end was easier to do, despite the complex control possibilities.

Scott Gage

April 16, 2015 at 11:32 pm

Just for the record the GOG version has both Amiga and PC versions included – since I played the game on Commodore 64 I remembered the gameplay being basic, but not too bad. Since I struggle with Amiga emulation (having never owned one) I snapped up the GOG version to see what I’d been missing out on, graphics wise. I was quick to go back to the PC version, though :)

Pedro Timóteo

April 17, 2015 at 8:55 am

As Jimmy said, the best combination of decent graphics and sound + improved gameplay may well be the Atari ST version. The PC one only supported EGA graphics and speaker sound, I think.

Rowan Lipkovits

April 17, 2015 at 6:41 am

The biggest question for Defender of the Crown for me has always been…

What does this guy have to do with it? http://www.jackzufeltspeaks.com/ On a few ports (eg. the Mac version) he gets top billing in the credits, as “presented by”. Is that just like oldschool Kickstarter?

Jimmy Maher

April 17, 2015 at 12:36 pm

Basically, yeah. Bob Jacob secured funding to start Cinemaware from a bunch of investors in the Salt Lake City area who were led by Jack M. Zufelt. So, Zufelt and his folks got the equivalent of a Hollywood executive-producer credit on the game, as the ones with the money.

I believe this is also how Cinemaware ended up working with Sculptured Software. They were local boys who had a lot of the same investors.

Wade

April 17, 2015 at 8:17 am

The Apple IIGS version is also excellent:

http://www.whatisthe2gs.apple2.org.za/defender-of-the-crown

… though Alex, who hosts the site I just linked, doesn’t like the game much.

Re: overall difficulty – I viewed the castle you pick to start in as being something of a difficulty setting. The castle at the bottom was easy to win from because it was out of the way. Starting in the middle, you’d more often get squeezed by other folks.

Rather than the game being super easy per se, I guess I found it telescoped quickly in one direction or the other. If you do well early in the game, you’re set. If you don’t, you’ll crash.

My only trick with the swordfighting was – be Geoffrey Longsword!

I have an issue of Games Machine magazine from around this period which joked about the lady on the cover of the game (not the ad shown in this article), dragging down both a horse and a knight with her chest.

Jimmy Maher

April 17, 2015 at 12:37 pm

You don’t get a choice of castles in the Amiga version. It’s random.

Todd Holcomb

April 20, 2015 at 12:47 pm

Loved this game on the Apple IIgs, and it’s a game that I still go back and play today, because you do feel like you’re part of a movie. The IIgs version isn’t easy – if your Saxon allies don’t capture many lands then it can be quite difficult. My strategy was / is to buy a catapult, build up a ton of soldiers, and outflank the enemy in battle. I never thought that knights were worth the price. And what’s up with your Saxons partners raiding your castle? With friends like that, who needs Normans?!

Felix

April 17, 2015 at 9:50 am

How ironic. The game that ushered in the era of graphics-fests already displayed the tension between graphics and gameplay. And you know… learning what the developer went through (boy, am I familiar with that kind of commission), I can’t blame him. Pro tip: you only have so much time and effort to sink into any given project. You can have great art, you can have great gameplay, or you can have a *compromise*. Then again, you can refuse to compromise and have a failure on your hands, just like 90% of the software projects out there.

But there’s more to the issue.

We call them computer *games*, and as it’s often been pointed out in IF circles, that skews the way we think about them. What makes computers unique as a medium is in fact *interactivity*. Remove that, and you have just a book or movie that just happens to unfold on a computer. That’s why people want *something* to do in their games, even if it’s as little as wandering around to uncover new sights. Walking simulators are successful, and that’s because the interactivity they offer is sufficient — sufficiently meaningful and/or interesting — for the player to be satisfied. (Of course, that’s because they reward their one mechanic, exploration, with gorgeous new sights at every turn. That’s where the art versus gameplay balance comes in.)

So you can have a game that provides a world to explore. You can have one where you can become enmeshed in a story. You can have one where there are always new depths of gameplay to uncover, and some people actually prefer those — that’s why you have chess players dedicating their entire life to one highly abstract game. In a way, all players are explorers; the only difference is what each of us would rather explore. It’s all fine.

The one thing that doesn’t work, the absolute worst you can do, is trying to spoon-feed the player a predetermined “experience” when they were expecting to, you know, craft their own. Defender of the Crown may have had terrible gameplay, but at least it made a genuine effort, and I think that’s why it worked so well. Without that part, all the art would have meant very little indeed.

And that’s not the conclusion I expected to reach at all. Oh well.

Jimmy Maher

April 17, 2015 at 12:45 pm

Yeah. I’ve often thought that many types of computers games are really ill-served by that label, as they have very little to do with traditional games. I flailed around in the past looking to clarify this and maybe even find a better appellation, but haven’t really gotten very far with it. Ludic narrative? Interactive experience? Nothing really works, and it doesn’t really matter anyway; the general public is unlikely to stop calling them “games” anytime soon.

Ken Rutsky

April 17, 2015 at 3:41 pm

This is a game I’d always heard about in magazines and from friends, but I’ve never actually played it.

The gameplay…in some ways, the mini-games make it sound similar to Sid Meier’s Pirates! Did DotC influence Pirates in any way?

Jimmy Maher

April 17, 2015 at 3:56 pm

No, don’t really think so. Pirates! appeared relatively early in 1987 if I recall correctly, and Defender of the Crown right at the end of 1986. So there wasn’t really time for it have much influence, especially considering that Pirates! was a design quite long in gestation. And Pirates! is vastly superior as a game design.

The strongest obvious influence on Pirates! was Seven Cities of Gold. But… we’ll get there soon. ;)

Carl

April 17, 2015 at 6:15 pm

I hope you have an article about Pirates. That was probably may favorite all time game.

You mention a lot of old-timers will think of Defender of the Crown when they think of the Amiga. Among my friends and acquaintances when they think of the Amiga, they think of Shadow of the Beast.

Firedragon

April 17, 2015 at 7:42 pm

I remember Defender of the Crown very well as I played it literally over hundred times. Recollecting my memory there are some interesting points I’m sure rarely anyone found out in the games 28 years existence.

– Sword fight: it’s basically clicking as fast as possible and moving your mouse constantly to the right side so you can advance. If you did enough castle raids your skill level actually went up!

– Jousting: you pointed the mouse cursor to the middle and just before the two opponents crushed into each other you moved it slightly to the left. et voilà, opponent down! But not too much or you would kill the horse and get rid of all your land from which you rarely recover

– Catapult: pulling it it fully down and pulling it three pixels up provided you with the first hit.

It is interesting how much I remember of it even after almost thirty years… it was a very immersive game for its time and it’s possibly the game I played most often in my life. Despite the obvious flaws it was atmospheric and that’s what counted.

Nathan

April 18, 2015 at 2:34 pm

I played the DOS port on CGA (so 320×200, 4 colors including the black background). There was an EGA version, but we didn’t have EGA. Speaker sound only, but still some of the best single-voice PC speaker music ever.

I would always pick Geoffrey Longsword, since that was the only way I could win a raid or rescue the princess. (I’m proud to say I was more embarrassed than titillated by the princess scenes.) Jousting was easy; you just had to aim at the center of the cross on his shield. I only found out about the possibility of killing a horse by searching the binary for text strings–it’s a pretty hard and stupid thing to do. Greek fire was important (almost as important as disease) for knocking the garrison forces down with your catapult before the actual fighting started. When you rescued the princess you got the lands of whichever Saxon she was kidnapped from.

Also, I would always restart until I randomly started in Clwyd. That way I could start off by claiming Gloucester and Hampshire, followed by the rich southeastern territories (Essex, Sussex, even Cambridge if I was lucky) and build up an army in the first few turns. Even with that strategic boost, it was along time before I ever won the game. The castle at Cornwall always seemed the last to fall, and I was sure if I ever beat it I would find the crown there. What a surprise when I finally won.

I enjoyed Defender of the Crown, and was always envious of the Amiga owners who could play that with the awesome original graphics and sound. I had no idea they were playing an inferior game.

Matthew W

April 19, 2015 at 7:48 am

Loved this article.

And loved Defender of the Crown, even though, as you point out, it’s not a particularly good game.

Kids today will never appreciate just how impressive it looked and sounded to someone who’s previous computer was an 8-bit ZX Spectrum. The music still gives me goosebumps.

I suspect that one of the movies that heavily influenced the graphics was the 1954 Prince Valiant film, especially the tournament scenes. Sadly DotC doesn’t feature Robert Wagner playing a Viking prince, something that would enhance every game.

Nate

April 26, 2015 at 12:47 am

Great article. I’d like to recommend the below video as a replacement for your link to Time Crystal. The video you linked doesn’t use the joystick so the saucer crashes and is a cracked version that skips part of the intro.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZ7UDnJF3kk

Jimmy Maher

April 26, 2015 at 6:30 am

I’m pretty sure I did see that version when I wrote the article. But what bugged me about it was the ugly “Unregistered HyperCam 2” (?) disclaimer and the way its aspect ratio is stretched way too far horizontally. That’s kind of a pet peeve of mine.

Chris

December 3, 2015 at 7:27 pm

What’s “sexist” about rescuing a woman? What if the sexes were reversed? Then I suppose the female rescuing an attractive man would be called “empowered.”

Peter Piers

January 13, 2016 at 8:41 pm

I believe it is sexist because women have a history of being the maiden in distress, and the poster perpetuates that.

But, don’t sweat it. People can find sexism everywhere, and there’s always a very good argument and a very good counter-argument. Losing battle. Best to get some popcorn, watch the battle from the bleachers, and have a clean conscience about your own games/works.

Chris

December 3, 2015 at 8:31 pm

That was meant in the spirit of debate that I love about your comments section, by the way — in case the succinctness caused it to appear grumpy.

I remember being so amazed as an early teen by the graphics in the C64 version of Defender of the Crown that in spite of having no clue as to how to beat the jousting or sword-fighting “scenes,” I played the game inordinately often. I reckoned that the missing manual explained my failure to beat it. Surely everything would be explained in the instructions!

I had a pirat… (ahem) “archived” version of the game. Whenever I found myself using a program regularly, my conscience would catch up with me and I’d buy the thing. I was disappointed to find that the manual didn’t really help. I was still glad to rid myself of the guilt, though. I guess all of those anti-piracy articles in Compute!’s Gazette, Run, etc. worked on me!

It’s funny to recall how much I loved the game, as I’m now one of those “game-play over graphics” guys you’ve mentioned. Still, whoever wrote the C64 adaptation worked wonders with sixteen colors.

DerKastellan

June 5, 2020 at 7:24 pm

The C64 version was quite solid. The graphics were good, and it was one of the games people took some interest in. Using catapults was always interesting – I had it down first of all the mini games. It played good with the joystick.

I never was quite sure how the swordfighting was supposed to work, but the mini games worked, all in all. Jousting was a bit frustrating, especially since it could take so long to set up – getting in place all in all.

The game looked good, it had this nice flair, it entertained. Funny that CinemaWare meant to appeal to adults – the game sure entertained a lot of pre-teens in its time. Adults often took some interest, too, though, because the game was not as twiddly and looked good.

harley gerdes

December 23, 2016 at 7:28 am

The NES version was awful. I own it and I played it with the help of an action replay, Its not a game that I revisit often but I think if I got a chance to play it on the Amiga or the ST, (which I own) I would definetly give if a second chance after reading this article. Those graphics are some of the best I have seen of a game of that vintage era. I never knew the story behind it, very fascinating indeed. I enjoyed reading it.

DZ-Jay

March 12, 2017 at 7:55 pm

This is the second time that you mention Marble Madness as an original Amiga title. Perhaps you are not aware but it was a popular arcade created by Atari Games prior to being ported to various systems, both 8- and 16-bits, including the Amiga. In fact, it was originally released in 1984. It wasn’t until 1986 that EA licensed it to port it to home-computers.

dZ.

Jimmy Maher

March 13, 2017 at 12:16 pm

Yes, I’m aware it was an arcade game first, but the Amiga version was unusually important as one of the platform’s showpiece games during the first couple of years.

DZ-Jay

March 13, 2017 at 4:36 pm

Gotcha. Perhaps there’s a way you can hint at that. My concern is that, as it stands, it suggests that it was first implemented for the Amiga computer, which may give the impression to some that your research is not as thorough as we know it is.

dZ.

mushu

July 14, 2017 at 12:53 am

Would be nice to see a writeup on the Queen of the PC Gaming Industry in the 80’s – Roberta Williams of Sierra. Also, the book by Steven Levy “Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution” is an excellent resource for the early days of hacking and gaming, highly recommended.

Jim Sachs

March 25, 2019 at 7:59 pm

Thanks for posting, and for your interest in ancient history, Jimmy :)

Jim Sachs

March 25, 2019 at 8:06 pm

P.S. — And thanks SO MUCH for displaying the graphics in the proper aspect ratio!

Jimmy Maher

March 26, 2019 at 8:56 am

Yeah, that’s a pet peeve of mine as well. ;)

Wolfeye M.

September 15, 2019 at 4:55 pm

I never played Defender of the Crown, was turned off by negative reviews when I was looking for classic games to play, so I can’t talk about it as a game. But, that art is amazing! I wouldn’t mind having some of it on my wall, it’s that good. Sachs and his team did an amazing job. It’s a shame that the game doesn’t seem to quite live up to the promise of the art.

Steve Pitts

February 17, 2022 at 5:00 pm

Should “when in a manner of a few days” be “in a matter of” or is this a strange American construct I’m unfamiliar with?

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2022 at 1:34 pm

Just a typo.;) Thanks!

Ben

September 1, 2022 at 8:18 pm

seemed much better suit -> seemed much better suited

Sach’s -> Sachs’

its its fictional -> its fictional

Jimmy Maher

September 2, 2022 at 8:36 am

Thanks!