I’ve already spent a lot of time on the history of one of the two great corporate survivors from the early years of videogames, Electronic Arts. But I’ve neglected the older of the pair, Activision, because that company originally made games only for consoles, a field of gaming history I’ve largely left to others who are far better qualified than I to write about it. Still, as we get into the middle years of the 1980s Activision suddenly becomes very relevant indeed to computer-gaming history. Given that, it’s worth taking the time now to look back on Activision’s founding and earliest days, to trace the threads that led to some important titles that are very much in my wheelhouse. In my view the single most important figure in Activision’s early history, and one that too often goes undercredited in preference to an admittedly brilliant team of programmers and designers, is Jim Levy, Activision’s president through the first seven-and-a-half years of its existence. So, as the title of this article would imply, one of my agendas today will be to do a little something to correct that.

The penultimate year of the 1970s was a trying time at Atari. The Atari VCS console, eventually to become an indelible totem of an era not just for gamers but for everyone, had a difficult first year after its October 1977 introduction, with sales below expectations and boxes piling up in warehouses. Internally the company was in chaos, as a full-on war took place between Nolan Bushnell, Atari’s engineering-minded founder, and its current CEO, Ray Kassar, a slick East Coast plutocrat whom new owners Warner Communications had installed with orders to clean up Bushnell’s hippie playground and turn it into an operation properly focused on marketing and the bottom line. Kassar won the war in December of 1978: Bushnell was fired. From that point on Atari became a very different sort of place. Bushnell had loved his engineers and programmers, but Kassar had no intrinsic interest in Atari’s products and little regard for the engineers and programmers who made them. The reign of Kassar as sole authority at Atari began auspiciously. Even before Bushnell’s departure, Kassar’s promotional efforts, with a strong assist from a fortuitous craze for a Japanese stand-up-arcade import called Space Invaders, had begun to revive the VCS; the Christmas of 1978, although nothing compared to Christmases to come, was strong enough to clear out some of those warehouses.

David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Larry Kaplan, and Alan Miller were known as the “Fantastic Four” at Atari during those days because the games they had (individually) programmed accounted for as much as 60 percent of the company’s total cartridge sales. Like most of Atari’s technical staff, they were none too happy with this new, Kassar-led version of the company. Trouble started in earnest when Kassar distributed a memo to his programmers listing Atari’s top-selling titles along with their sales, with an implied message of “Give us more like these, please!” The message the Fantastic Four took away, however, was that they were each generating millions for Atari whilst toiling in complete anonymity for salaries of around $30,000 per year. Miller, whose history with Atari went back to playing the original Pong machine at Andy Capp’s Tavern and who was always the most vocal and business-oriented of the group, drafted a contract modeled after those used in the book and music industries that would award him royalties and credit, in the form of a blurb on the game boxes and manuals, for his work; he then sent it to Kassar. Kassar’s reply was vehemently in the negative, allegedly comparing programmers to “towel designers” and saying their contribution to the games’ success was about as great as that of the person on the assembly line who put the packages together. Miller talked to Crane, Whitehead, and Kaplan, convincing them to join him in seeking to start their own company to write their own games to compete with those of Atari. Such a venture would be the first of its kind.

The Fantastic Four, 1980: from left, Bob Whitehead, David Crane, Larry Kaplan, and Alan Miller (standing)

Through the lawyer they consulted, they met Jim Levy, a 35-year-old businessman who had just been laid off after six years at a sinking ship of a company called GRT Corporation, located right there in Sunnyvale, California, also home to Atari. GRT had mainly manufactured prerecorded tapes for music labels, but had also run a few independent labels of their own on the side. Eager to break into that other, creative part of the industry, Levy had come up with a scheme to take the labels off their erstwhile parent’s hands, and had secured $350,000 in venture capital for the purpose. But when his lawyer introduced him to the Fantastic Four that plan changed immediately. Here was a chance to get in on the ground floor of a whole new creative industry — and that really was, as we shall see, how Levy regarded game making, as a primarily creative endeavor. He convinced his venture capitalists to double their initial investment, and on October 1, 1979, after the Fantastic Four had one by one tendered their resignations to Atari as an almost unremarked part of a general brain drain that was going on under Kassar’s new regime, VSYNC, Inc., was born. But that name, an homage to the “vertical sync” signal that Atari VCS programmers lived and died by (see Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost’s Racing the Beam), obviously wouldn’t do. And so, after finding that “Computervision” was already taken, Levy came up with “Activision,” a combination of “action” and “vision” — or, if you like, “action” and “television.” It didn’t hurt that the name would come before that of the company they knew was doomed to become their arch-nemesis, Atari, in sales brochures, phone books, and corporate listings. By January of 1980, when they quietly announced their existence to select industry insiders at the Consumer Electronics Show — among them a very unhappy and immediately threatening Kassar — Activision included 8 people. By that year’s end, it would include 15. And by early 1983, when Activision 1.0 peaked, it would include more than 400.

Aware from the beginning of the potential for legal action on Atari’s part, Activision’s lawyer had made sure that the Fantastic Four exited Atari with nothing but the clothes on their backs. The first task of the new company thus became to engineer their own VCS development system. Much of this work was accomplished in the spare bedroom of Crane’s apartment, even before Levy got the financing locked down and found them an office. Activision was thus able to release their first four games in relatively short order, in July of 1980. Following Atari’s own approach to naming games in the early days, Dragster, Boxing, Checkers, and Fishing Derby had names that were rather distressingly literal. But the boxes were brighter and more exciting than Atari’s, the manuals all included head shots of their designers along with their signatures and personal thoughts on their creations, and, most importantly, most gamers agreed that the quality was much higher than what they’d come to expect from Atari’s own recent releases. Activision would refine their approach — not to mention their game naming — over the next few years, but these things would remain constants.

In spite of the example of a thriving software industry on early PCs like the TRS-80 and Apple II, it seems to have literally never occurred to Atari that anyone could or would do what Activision had done and develop software for “their” VCS. That lack of expectation had undoubtedly been buttressed by the fact that the VCS, a notoriously difficult machine to program for even those in the know, was a closed box, its secrets and development tools secured behind the new hi-tech electric door locks Kassar had had installed at Atari almost as soon as he arrived. The Fantastic Four, however, carried all that precious knowledge around with them in their heads. Atari sued Activision right away for alleged theft of “trade secrets,” but had a hard time coming up with anything they had actually done wrong. There simply was no law against figuring out — or remembering — how the VCS worked and writing games for it. And so Atari employed the time-honored technique of trying to bury their smaller competitor under lawsuits that would be very expensive to defend regardless of their merits. That might have worked — except that Activision made an astonishingly successful debut. This was the year that the VCS really took off, and Activision was there to reap the rewards right along with Atari, selling more than $60 million worth of games during their first year. The levelheaded Levy, who had anticipated a legal storm from the beginning, simply treated it as another tax or other business expense, budgeting a certain amount every quarter to keeping Atari at bay.

Under Levy’s guidance, Activision now proceeded to write a playbook that many of the publishers we’ve already met would later draw from liberally. Activision’s designer/programmers were always shown as cool people doing cool things. Steve Cartwright, designer of Barnstorming, was photographed, with scarf blowing rakishly in the wind, about to take to the skies in a real biplane; Carol Shaw, designer of River Raid and one of the vanishingly small number of female programmers writing videogames, appeared on her racing bike; Larry (no relation to Alan) Miller, designer of Enduro, could be seen perched on the hood of a classic car. Certainly Trip Hawkins would take note of Activision’s publicity techniques when he came up with his own ideas for promoting his “electronic artists” like rock stars. Almost from the beginning Activision fostered a sense of community with their fans through a glossy newsletter, Activisions, full of puzzles and contests and pictures and news of the latest goings-on around the offices in addition to plugs for the newest games — a practice Infocom and EA among others would also take to heart. Activision, however, did it all on a whole different scale. By 1983 they were sending out 400,000 copies of every newsletter issue, and receiving more than 10,000 pieces of fan mail every week.

In those early years Activision practically defined themselves as the anti-Atari. If Atari was closed and faceless, they would be open and welcoming, throwing grand shindigs for press and fans to promote their games, like the “Barnstorming Parade,” featuring, once again, Cartwright in a real airplane; the “Decathlon Party,” featuring 1976 Olympic Decathlon Gold Medal winner Bruce Jenner, to promote The Activision Decathlon; or the “Rumble in the Jungle” to promote their biggest hit of all, Crane’s Pitfall!. While, as Jenner’s presence will attest, they weren’t above a spot of celebratory endorsing now and again, they also maintained a certain artistic integrity in sticking to original game concepts and refusing any sort of licensing deals, whether of current arcade hits or media properties. This again placed them in marked contrast to Atari, who, in the wake of their licensed version of Taito’s arcade hit Space Invaders that had almost singlehandedly transformed the VCS from a modest success to a full-fledged cultural phenomenon in the pivotal year of 1980, never saw a license they didn’t want. Our games, Levy never tired of saying, are original works that can stand on their own merits. As for the licensed stuff: “People will take one look because they know the movie title. But if an exciting game isn’t there, forget it. Our audiences are too sophisticated. You can’t fool them.” Such respect for his audience, whether real or feigned or a bit of both, was another thing that endeared Activision to them.

Released in April of 1982 just as the videogame craze hit its peak — revenues that year reached fully half those of the music industry — Pitfall! was Activision 1.0’s commercial high-water mark, selling more than 4 million copies, more than any of Atari’s own games except Pac-Man. Pitfall! would go on to become the urtext of an entire genre of side-scrolling platform games. In more immediate terms, it made Crane something of a minor celebrity as well as a very wealthy young man indeed; one magazine even dared to compare his earnings from Pitfall! with those of Michael Jackson from Thriller, although that was probably laying it on a bit thick. Meanwhile four other Activision games — Laser Blast, Kaboom!, Freeway, and River Raid — had passed the 1 million mark in sales, and dozens of other new publishers had followed Activision’s example by rolling up their sleeves, figuring out how the VCS worked and how they could develop for it, and jumping into the market. The resulting flood of cartridges, many of them sold at a fraction of Activision’s price point and still more of them substandard even by Atari’s less than exacting standards, would be blamed by Levy for much of what happened next.

In April of 1983, Levy confidently predicted in his keynote speech for The First — and, as it would turn out, last — Video Games Conference that the industry would triple in size within five years. In June, Activision went public, creating a number of new millionaires. It was, depending on how you look at it, the best or the worst possible timing. Just weeks later began in earnest the Great Videogame Crash of 1983, and everything went to hell for Activision, just as for the rest of the industry. Activision had always been a happy place, the sort of company whose president could suddenly announce that he was taking everyone along with their significant others to Hawaii for four days to celebrate Pitfall!‘s success; where the employees could move their managers’ offices en masse into the bathrooms for April Fool’s without fear of reprisal; whose break rooms were always bursting with doughnuts and candy. Thus November 10, 1983, was particularly hard to take. That was the day Levy laid off a quarter of Activision’s workforce. It was his birthday. It was also only the first of many painful downsizings.

Levy had bought into the contemporary conventional wisdom that home computers were destined to replace game consoles in the hearts and minds of consumers, that the home-computer market was going to blow up so big as to dwarf the VCS craze at its height. His plan was thus to turn Activision into a publisher of home-computer software rather than game cartridges. His biggest problem looked to be bridging the chasm that lay between the recently expired fad of the consoles and the projected sustained domination of the home computer. The painful fact was that, even on the heels of a hugely successful 1983, all of the home-computer models combined still had nowhere near the market penetration of the Atari VCS alone at its peak. There simply weren’t enough buyers out there to sustain a company of the size to which Activision had so quickly grown. The only way to bridge the chasm was to glide over on the millions they had socked away in the bank during the boom years whilst brutally downsizing to stretch those millions farther. Activision 2.0 would have to be, at least for the time being, a bare shadow of Activision 1.0’s size. Yet “the time being” soon began to look like perpetuity, especially as the cash reserves began to dry up. In 1983, Activision 1.0 had revenues of $158 million; in 1986, three years into Levy’s remaking/remodeling, Activision 2.0 had revenues of $17 million. The fundamental problem, which grew all too clear as Activision 2.0’s life went on, was that the home-computer boom had fizzled about a decade early and about 90 percent short of its expected size.

With Activision, despite the frantic downsizing, projected to lose $18 million in 1984, when Columbia Pictures made it known that they would be interested in letting David Crane do a game based on their new movie Ghostbusters, Levy quietly forgot all his old prejudices against licensed products. Ghostbusters the game was literally an afterthought; the movie had already been in theaters a week or two when Activision and Columbia started discussing the idea. The deal was closed within days, and Crane was told he had exactly six weeks to come up with the game before Ghostbusters mania died down — which was just as well, as he was planning to get married in six weeks. Exactly these sorts of external pressures had undone Atari licensed games like Pac-Man and E.T., and were a big part of the reason that Levy had heretofore avoided licenses. Luckily, Crane already had been working on a game for the Commodore 64 he called Car Wars (no apparent relation to the Steve Jackson Games board game, the license for which was held by Origin Systems), which had the player undertaking a series of missions whilst racing around a city map battling other vehicles. Each successful mission earned money she could use to upgrade her car for the next, more difficult level. Crane realized it should be possible to retrofit ghosts and lots of other paraphernalia from the movie onto the idea. Realizing that he couldn’t possibly do it all on his own, he recruited a team of four others to help him. Ghostbusters thus became the first Activision game to abandon the single-auteur model of development that had been the standard until then. In its wake almost every other project also became a team project, a concession to the technical realities of developing for the more advanced Commodore 64 and other home computers versus the old VCS. With the help of his assistants, Crane was able to add many charming little touches to Ghostbusters, like sampled taglines from the movie (“He slimed me!”) and a chiptunes version of Ray Parker, Jr.’s monster hit of a theme song, complete with onscreen words and a bouncing ball to help you sing along.

David Crane was Activision’s King Midas. Despite its rushed development, Ghostbusters turned out to be a very playable game, even a surprisingly sophisticated one, what with its CRPG-like in-game economy and the thread of story that linked all of the ghost-busting missions together. It even has a real ending, with the slamming of the dimension door that’s been setting all of these ghosts loose in our universe. Released in plenty of time for Christmas 1984 and doubtless buoyed by the fact that Ghostbusters the movie just kept going and going — it would eventually become the most successful comedy of the 1980s — Ghostbusters became Activision 2.0’s biggest hit by a light year and one of the bestselling Commodore 64 games of all time, selling well into the hundreds of thousands. Like relatively few Commodore 64 games but almost all of the real blockbusters, it became hugely popular in both North America and Europe, where Activision, unlike most of their peers who published there if at all through the likes of U.S. Gold, had set up a real semi-autonomous operation — Activision U.K. — during the boom years. And it was of course widely ported to other platforms popular on both sides of the pond.

It’s at this point that Levy’s story and Activision’s get really interesting. Having proved through Ghostbusters that his company could make the magic happen on the Commodore 64 as well as the Atari VCS, however much more modest the commercial rewards for even a huge hit on the former platform were destined to be, Levy now began to push through a series of aggressively innovative, high-concept titles, often over the considerable misgivings of the board of directors with which Activision’s IPO had saddled him. I don’t want to overstate the case; it’s not as if Levy transformed Activision overnight into an art-house publisher. The next few years would bring plenty of solid action games alongside the occasional adventure as well as, what with Activision having popped the lid off this particular can of worms to so much success, more licensed titles: Aliens, Labyrinth, Transformers, and, just to show that not all licenses are winners, a computerized adaptation of Lucasfilm’s infamous flop Howard the Duck that managed to be almost as bad as its inspiration. Yet betwixt and between all this expected product Levy found room for the weird and the wacky and occasionally the visionary. He made his agenda clear in press interviews. Rhetorically drawing on his music-industry experience despite the fact that he had never actually worked on the creative side of that industry, he cast Activision’s already storied history as that of a plucky artist-driven indie label that went “head to head with the majors” and thereby proved that “the artist can be trusted,” whilst chastising competitors for “a certain stagnation in creative style, concept, and content.” The game industry was — or should be — driven by its greatest assets, its creators. The job of him and the other business-oriented people was just to facilitate their art and to get it before the public.

Writing a game is close to the whole concept of songwriting and composing. Then you get involved later on with the ink-and-paper people for packaging. There are a lot of similarities between the record business and what we do.

There was a certain amount of calculation in such statements, just as there was in Trip Hawkins’s campaigns on behalf of his own electronic artists. Yet, also as in Hawkins’s case, I believe the core sentiment was very sincere. Levy genuinely did believe he was witnessing the birth of a new form (or forms) of art, and genuinely did feel a responsibility to nurture it. Garry Kitchen, a veteran programmer who had joined Activision during the boom years, tells of how Levy during the period of Activision 2.0 kept rejecting his ideas for yet more simple action games: “Do something different, innovate!” How many other game-industry CEOs can you imagine saying such a thing then or now?

At this point, then, I’d like to very briefly tell you about a handful of Activision’s titles from 1985 and 1986. In some cases more interesting as ideas than as playable works, no one could accuse any of what follows of failing to heed Levy’s command to “innovate!” Some aren’t actually games at all, fulfilling another admonition of Levy to his programmers: to stop always thinking in terms of rules and scores and winners and losers.

The first fruit of the creative pressure Levy put on Kitchen was The Designer’s Pencil. Yet another impressive implementation of a Macintosh-inspired interface on an 8-bit computer, The Designer’s Pencil is, depending on how you look at it, either a thoroughly unique programming environment or an equally unique paint program. Rather than painting directly to the screen, you construct a script to control the actions of the eponymous pencil. You can also play sounds and music while the pencil is about its business. A drawing and animation program for people who can’t draw and a visual introduction to programming, The Designer’s Pencil is most of all just a neat little toy.

Responding to users of The Designer’s Pencil who begged for ways to make their creations interactive, Kitchen later provided Garry Kitchen’s GameMaker: The Computer Game Design Kit. Four separate modules let you make the component pieces of your game: Scenes, Sprites, Music, and Sound. Then you can wrap it all together in a blanket of game logic using the Editor. Inevitably more complicated to work with than The Designer’s Pencil, GameMaker is still entirely joystick-driven if you want it to be and remarkably elegant given the complexity of its task. It was by far the most powerful software of its kind for the Commodore 64, the action-game equivalent of EA’s Adventure Construction Set. In a sign of just how far the industry had come in a few years, GameMaker included a reimplementation of Pitfall!, Activision’s erstwhile state-of-the-art blockbuster, as a freebie, just one of several examples of what can be done and how.

Described by its creator Russell Lieblich as a “Zen” game, Web Dimension has an infinite number of lives, no score, and no time limit. The ostensible theme is evolution: levels allegedly progress through atoms, planets, amoebae, jellyfish, germs, eggs, embryos, and finally astronauts. But good luck actually making those associations. The game is best described as, as a contemporary reviewer put it, “a musical fantasy of color, sight, and sound,” on the same wavelength as if less ambitious than Automata’s Deus Ex Machina. As with that game, the soundtrack is the most important part of Web Dimension. Lieblich considered himself a musician first, programmer second, and not actually much of a gamer: “I’m not really into games, but I love music, so I designed a musical game that doesn’t keep score.” Like Deus Ex Machina not much of a game in conventional terms, Web Dimension is interesting as a piece of interactive art.

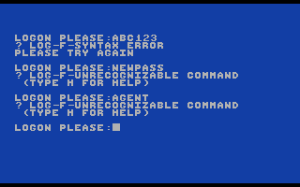

Hacker begins with a screen that’s blank but for a single blinking login prompt. You’re trying to break into a remote computer system with absolutely nothing to go on. Literally: in contrast to the likes of the Ultima or Infocom games, Hacker‘s box contained only a card telling how to boot the game and an envelope of hints for the weak and/or frustrated. Discovering the rules that govern the game is the game. Designed and programmed by Steve Cartwright, creator of Barnstorming amongst others, it was another achievement of an Activision old guard who continued to prove they had plenty of new tricks up their sleeves. This weird experiment of a game actually turned into a surprising commercial success, Activision 2.0’s second biggest seller after Ghostbusters. Playing it is a disorienting, sinister, oddly evocative experience until you figure out what’s going on and what you’re doing, whereupon it suddenly all becomes anticlimactic. “Anticlimactic” also best describes the sequel, Hacker II: The Doomsday Papers; Hacker is the kind of thing that can only really work once.

Little Computer People is today the most remembered creation of Activision’s experimental years, having been an important influence on a little something called The Sims. It’s yet another work by the indefatigable David Crane, his final major achievement at Activision. The fiction, which Crane hewed to relentlessly even in interviews, has you helping out as a member of the Activision Little Computer People Research Group, looking into the activities of the LCPs who have recently been discovered living inside computers. When you start the program you’re greeted by a newly built house perfect for the man and his dog who soon move in. Every single copy of Little Computer People contained a unique LCP with his own personality, a logistical nightmare for Activision’s manufacturing process. He lives his life on a realistic albeit compressed daily schedule, with 24 hours inside the computer passing in 6 outside it. Depending on the time of day and his personality and mood as well as your handling, the little fellow might prefer to relax with a book in his favorite armchair, play music on his piano, exercise, chat on the phone, play with his dog, watch television, listen to the record collection you’ve (hopefully) provided, or play a game of cards with you — when he isn’t sleeping, brushing his teeth, or showering, that is. You can try to get him to do your bidding via a parser interface, but if you aren’t polite enough about it or if he’s just feeling cranky the answer is likely to be a big fat “No!”

While Little Computer People was frequently dismissed as pointless by the more goal-oriented among us, other players developed strong if sometimes dysfunctional attachments to their LCPs. For example, in an article for Retro Gamer, Kim Wild told of her fruitless year-long struggle to get her hygienically challenged LCP just to take a shower already. In its way Little Computer People offered as many tempting mysteries as any adventure game. Contemporary online services teemed with controversy over the contents of a certain upstairs closet into which the LCP would periodically disappear, only to reappear with a huge smile on his face. The creepy majority view was that he had a woman stashed in there, although a vocal minority opted for the closet being a private liquor cabinet.

While it didn’t sell in anything like the quantities of some of Crane’s other games, Little Computer People was a moderate success. Further cementing its connection to The Sims, Crane and Activision planned a series of expansions that would have added new houses and other environments for the LCPs and maybe even the possibility of having more than one of them, and thus of watching them interact with one another instead of only with their dogs and their players. For reasons that will have to wait for a future article, however, that would never happen.

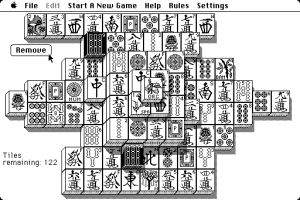

Activision’s first notable release for the new 68000-based machines was Shanghai. A simple solitaire tile-matching exercise that uses mahjong tiles — and not, it should be emphasized, an implementation of the much more complex actual game of mahjong — Shanghai was created by Brodie Lockard, a former gymnast who’d become paralyzed following a bad fall and used his “solitaire mahjong” almost as a form of therapy in the years that followed. Particularly in its original Macintosh incarnation, it’s lovely to look at and dangerously addictive. Like many of Activision’s experimental titles of the period, Shanghai cut against most of the trends in gaming of the mid-1980s. Its gameplay was almost absurdly simple while other games were reveling ever more in complexity; it was playable in short bursts of a few minutes rather than demanding a commitment of hours; its simple but atmospheric calligraphic visuals and feel of leisurely contemplation made a marked contrast to the flash and action of other games; its pure abstraction was the polar opposite to other games’ ever-growing focus on the experiential. Moderately successful in its day, Shanghai was perhaps the most prescient of all Activision’s games from this period, forerunner to our current era of undemanding, bite-sized mobile gaming. Indeed, it would eventually spawn what seems like a million imitators that remain staples on our smartphones and tablets today. And it would also spawn, the modern world being what it is, lots and lots of legal battles over who actually invented solitaire mahjong; there’s still considerable debate about whether Lockard merely adopted an existing Chinese game to the computer or invented a new one from whole cloth.

There are still other fascinating titles whose existence we owe to Jim Levy’s Activision 2.0. In fact, I’m going to use my next two articles to tell you about two more of them — inevitably, given our usual predilections around here, the most narrative-focused of the bunch.

(Lots of print sources for this one, including: Commodore Magazine of June 1987, February 1988, and July 1989; Billboard of June 16 1979, July 14 1979, September 15 1979, June 19 1982, and November 3 1984; InfoWorld of August 4 1980 and November 5 1984; Compute!’s Gazette of March 1985; Creative Computing of September 1983 and November 1984; Antic of June 1984; Retro Gamer 18, 25, 79, and 123; Commodore Horizons of May 1985; Commodore User of April 1985; Zzap! of December 1985; San Jose Mercury of February 18 1988; New York Times of January 13 1983; Commodore Power Play of October/November 1985; Lodi News Sentinel of April 4 1981; the book Zap!: The Rise and Fall of Atari by Scott Cohen; and the entire 7-issue run of the Activisions newsletter. Online sources include Gamasutra’s histories of Activision and Atari and Brad Fregger’s memories of Shanghai‘s development.)

John G

November 5, 2014 at 5:00 pm

I was just thinking about Little Computer People this week and wondering about a number of aspects that still seem mysterious to me. I still remember when, as a kid, I believed someone’s joke at the local computer store that if I made my LCP, a gray-haired bachelor named Taylor, happy enough he would invite his friends over and throw a party. But I tried and tried and nothing happened.

I was Googling this week and read that if your disk became damaged, Activision would bring your LCP back to life by carefully extracting his personality traits from the old disk. But I still wonder about aspects of LCP life that, unlike in The Sims, happen behind the scenes.

For example, every disk has its own, one-of-a-kind LCP with his own name and personality–in what seemed at the time to fit in with the craze of every Cabbage Patch Kid doll being similarly unique. But I still wonder about the possible range of character traits, looks and names that the computer has to work with the first time the disk loads and it runs the LCP genesis process.

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2014 at 8:26 am

Retro Gamer’s article describe each LCP’s “brain” as being stored in a single block on each disk, meaning it could occupy at most 256 bytes. The disks were otherwise identical. So, we’re not talking about hugely sophisticated AI here. I suspect that, as with so many other pieces of software artistry dating back at least to Eliza, most players would be shocked at how *little* was actually going on under the hood. Much of the art of design in these days was of creating the *impression* of complexity. There’s only so much you can ultimately do in 64 K.

Zibri

August 30, 2020 at 1:11 pm

The “personality” was just a serial number.

The format is XXXXYYYYNVTCA and must be read from right to left.

First LCP is 00000000NVTCA, second is 10000000NVTCA etc etc

From that serial number is generated the name of the LCP and his dog color, the “personality” and shirt/hars/cap/glasses and many other elements.

All it was needed was to read 16 bytes from track 18 sector 17 of the disk.

The STATE of the game is instead saved at track 1 sector 4.

Those are the only two difference between each and every copy of LCP.

Alas, there were 2 disk versions: one released in 1985 and another in 1986.

So the total possible range is 10^8 = 100.000.000 100 million LCPs.

The total number of names was 256 but every LCP had unique features and looks.

Alex Smith

November 5, 2014 at 5:10 pm

Fun read as always, just wanted to point out a couple of small mistakes and additions.

First, your brief remarks on the VCS are not quite accurate. The system performed very well on release, selling out the entire 400,000 unit production run. Then two things happened in 1978: the company experienced an unacceptable level of customer returns due to quality control issues, and retailers resisted building programmable console inventory for Christmas due to a variety of economic factors I will not get into here. Atari had hoped to double sales of the VCS in 1978, but retailers ordered at 1977 levels. That’s why those systems backed up in warehouses. Consumers actually bought almost everything they could in 1978: it was the retailers who constrained supply. I know that’s more detail than you need to go into for this post, but I just wanted to point out it was selling more than “tens of thousands.”

Second, I know you are generalizing in the interest of summarizing, but the Kassar portrayal is a bit unnuanced. R&D actually increased under Kassar and there were a variety of advanced console and computer projects under development at any given time under his watch. Few of these came to market, however, due in part to company politics. I also think its unfair to say he had “no regard” for his engineers. Kassar understood you needed good people to create good products, but he appears to have never understood that creating excellent games required a unique combination of creativity and technical knowledge that was rare in those days and therefore valuable. He certainly undervalued his engineers, but he did not dismiss them completely. Eventually, Atari woke up and instituted a royalty program, but all they really did was close the barn door after the horses were already gone.

My final point relates to the Ghsotbusters opportunity. Credit for that goes to Greg Fischbach, Activision’s president of international and later founder of Acclam Entertainment. Fischbach had been a music industry lawyer and had a lot of contacts in the entertainment industry. He knew the head of Columbia Pictures, who told him about the forthcoming movie. Fischbach then brought it to Activision.

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2014 at 8:06 am

I don’t want to get too far down into the weeds on some of this for obvious reasons, but if you could point to a source or two on the early VCS sales figures that would be super helpful for me to feel confident about making an edit or two. Most of what I’ve found describes an early surge (relatively speaking), followed by sales dropping down to a disappointing dribble — i.e., “measured in the tens of thousands” — for most of 1978, then picking up again that Christmas thanks to Kassar’s advertising, the Space Invaders arcade craze, and presumably just the plain old standard Christmas buying frenzy. As far as the details of retail order levels, etc., that is as you’ve surmised a bit more than I feel the need to get into here.

On Kassar: I believe it’s fairly clear that he did *initially* slash R&D. In Zap! by Scott Cohen, Bushnell lists the desire of Kassar and Kassar’s boss Manny Gerard (the Warner executive who orchestrated the Atari acquisition) to slash R&D budgets as the main impetus behind the November 1978 blowup between Bushnell and Gerard that resulted in the former’s “voluntary firing.” Bob Brown, head of Atari’s main team of 30 engineers, described in the same book his shock at Kassar’s budget-slashing — “Kill R&D and you’re killing the company’s future” — and makes it the main reason for the mass exodus of Atari’s original engineering staff. I understand that Atari later restarted R&D — thus your “closing the barn door after the horses were already gone” — even hiring prestigious names like Alan Kay, but in this narrow context of the time around the Fantastic Four’s departure I feel like my portrayal is accurate.

On Ghostbusters: I’d read of Fischbach’s role in my research, but, again, I wasn’t ready to get too deeply into the details of the backstage deal-making for what is ultimately a fairly broad historical summary of an article. But credit where’s it’s due and all, so thanks for that. :)

Alex Smith

November 6, 2014 at 3:59 pm

Happy to provide some sources.

Atari VCS sales in 1977:

The Southeast Missourian, June 15, 1978

These were the sales Atari reported at the time, and more contemporary sources have continued to take their word for it: see for example this case study

A Berstein Research strategic analysis released in December 1982 claimed sales of 300,000 units rather than 400,000, and that is probably the sales claimed by the chart in IEEE Spectrum that Scott references below too, though charts like that are difficult to gauge.

Scott’s claim of 250,000 appears to come from statements made to that effect by Joe Decuir, who was a member of the VCS development team on page 7 of this webzine, but he is not a particularly reliable source for this information not being involved in sales and attempting to remember years after the fact. He also claims that figure from the IEEE chart in his FAQ, but I get the feeling they are claiming the same 300,000 as Berstein. Its only 50,000 units though, so its not that material.

1978 sales:

Atari: From Cutoffs to Pinstripes by Steve Bloom

Design Case History: The Atari Video Computer System from the March 1983 issues of IEEE Magazine

These sources differ slightly on the details, but they both agree that Atari manufactured 800,000 units and retailers refused to stock many of them. Manny Gerard has attested in several places, including Tristan Donovan’s Replay, that the VCS was a hit in 1978, so those units at retail sold, but Atari was left with 300,000-400,000 units backed up in warehouses along with their suddenly worthless dedicated console stock. Bernstein also claims 400,000 sold, which jives with Keenan’s comments to Bloom that 400,000 failed to sell in 1978.

Note that Scott’s claim of 750,000 units below is a typo: his FAQ claims 500,000 units in 1978 and 750,000 lifetime sales by the end of 1978.

R&D

The best source for this is Atari Inc Business is Fun by Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, which has multiple chapters devoted to R&D work at both Atari proper and its Cyan Engineering subsidiary in Grass Valley. There is no real indication in that book that Atari suddenly scrapped a bunch of products or cut R&D spending from any source I have ever seen. I am sure resources were shifted and people were let go as is typical in any regime change, but R&D was a strong component all along. I mean, they lured Alan Kay to the company to run R&D when Al Alcorn left a few years later, though he ended up calling that one of the least productive periods of his life.

The main source for this contention about ending R&D appears to come from the Cutoffs to Pinstripes article linked above, but it makes little sense. At the time, Bob Brown was in charge of the microelectronics division of Atari, which encompassed both VCS and dedicated console hardware and software development. He was not involved with pure R&D, which was run by Al Alcorn. I do not know who these thirty employees were that Atari let go, but work continued at the time on Atari’s next-gen console (which was later transformed into the Atari 400/800 computer), as well as on a line of electronic handheld games and a video phone that would eventually become the Ataritel project. Certainly some projects were cancelled, such as Kermit the robot at Cyan, but that’s different from making deep cuts.

As a final note, I jsut want to point out that Zap has been pretty thoroughly discredited by modern video game history research. Its useful for some of the direct quotes from people like Steve Bristow, Howie Delman, and Don Osborne, but the rest is filled with errors. Al Alcorn has long maintained that Cohen just made most of it up, and while that’s probably an extreme position, the sentiment is understandable. While Bushnell and Gerard have disagreed on some of the details of that November budget meeting, they have gone on the record in sources like Kent’s Ultimate History of Video Games and Replay to say that the budget meeting blowup was about Bushnell wanting to dump the VCS immediately and build something else and Gerard and Kassar’s belief that the VCS had a lot of mileage left in it: a view that was proven true when Atari ended up having a good Christmas that year despite the limited stock resulting from retailer refusal to build inventory.

I know console history is not really your bag, so I’m sorry to take you on this little detour; I just want to make sure that certain long-standing myths relating to the early years of Atari don’t inadvertently end up being perpetuated. People like Marty, Curt, and myself are working to provide more accurate portrayals of this period, but we are probably still years away from overturning the “conventional wisdom” created by sloppy research in books like Zap. I feel you are helping perform a similar service for computer games, which is why I continue to appreciate and admire your work.

Alex Smith

November 6, 2014 at 4:04 pm

D’oh, mislinked my blog in my name in the comment above. Should link here

Scott Stilphen

April 21, 2017 at 3:02 am

Since I can’t reply to your Nov. 7th post, I’ll reply to this one.

“Well Scott, that was a surprising and completely unwarranted personal attack.”

How is that, exactly? Everything I wrote is the truth. Yes, Vendel is an ex-felon. You clearly don’t want to accept that, but I did my research on him, and his faults go well beyond insulting people such as Nolan Bushnell (his comments regarding Nolan and his wife were truly despicable, even for him), or Jeff Minter, or James Morgan… He’s also returned to his old felonious ways by taking some $30,000 in prepaid orders for some 7800 device (since 2010!) that was supposedly ready to ship the 1st day it was announced, and yet.. nobody received it, and nobody received a refund for it. But please, continue to enable and support people like that. What would this hobby ever do without them…

“I don’t really have an ax to grind with anyone as you seem to, so in the future kindly leave me (and Jimmy’s comments section) out of any personal feuds you have with Messrs. Goldberg and Vendel.”

Alex, you’re the one who brought up that awful book and even though you admit it’s “flawed” and its authors “unprofessional”, you stand by them. If you’re the scholar you claim to be, the first thing you should do is throw that book away, because it’s done more to skew Atari’s history than any other publication before it. One of the “authors”, Marty Goldberg, has taken ‘historial revisioning’ to the extreme, from rampant Wikipedia page editing (for example, he’s convinced VCS Adventure came out prior to 1980, but yet doesn’t have a shred of proof to back it up), to posting on countless forums in an effort to support his wild claims (most of the UK forums have all but banned him for all the attempts he’s made to rewrite Atari UK’s history). No Alex, these people do not deserve your support or your respect, and this hobby would have been far better off without them. The only ‘axe’ I have to grind is with those who aren’t out to help this hobby but merely out to help themselves. If that’s too ‘completely unwarranted’ for you, well, it is what it is.

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2014 at 4:45 pm

Thanks for this! I made some fairly innocuous edits to hopefully remove anything inaccurate or questionable without changing the thrust of the opening paragraph. I do have Business Is Fun, but even leaving aside the lack of editing and all of the grammar problems I must confess that I find it pretty impenetrable, just an endless stream of anecdotes with no index and no strong authorial voice to help make sense of it all. If your long-term intention is to mold all of that material into something more readable and comprehensible, you’ll be doing the world a great service! Based on your blog, which I do peek at now and again, you’re off to a great start.

Scott S.

November 7, 2014 at 3:57 am

“Note that Scott’s claim of 750,000 units below is a typo: his FAQ claims 500,000 units in 1978 and 750,000 lifetime sales by the end of 1978.”

Yes, it was a typo on my part (I don’t have the ability to edit here).

I wouldn’t put too much stock in that SouthEast Missourian article. For one thing, Atari is referred to as Atari Corp, not Atari Inc. (it wasn’t ‘Corp’ until Tramiel bought it in 1984). For another, the 400k sales figure is being given by an Atari spokesperson (Ken George), so that should always be questioned, especially when it claims that many were sold in 1977, and the VCS was only on the market for the last 3 months of that year. Thirdly, George states they sold for $189. The original retail price for the VCS was anywhere between $200 and $250. Large department stores like Service Electric sold it for that price, but not every store could.

No, I don’t base my info on Joe Decuir’s statement, Alex – I’ve never referenced him for it, have I? As for Decuir not being a reliable source of info, I’d take his account over some company spokesperson’s any day. Spokespersons are paid for their comments; employees aren’t.

Btw, all the relevant issues of IEEE spectrum can be found here:

http://www.2600connection.com/library/magazines/magazines.html

“The best source for this is Atari Inc Business”

Of course you’re going to say that – you just admitted you’re working with them! No, it’s not the best source, and it’s certainly not the only source. That book is a complete disaster on every level. It’s worthless as a research tool, due to the lack of an index. It’s unreadable, because neither of them possesses even the most rudimentary skills any writer needs. So what exactly are their qualifications for being experts on the subject? One is known for illegally dumpster-diving on Atari’s property and stealing a bunch of hardware and paperwork (i.e. his ‘research papers’ and ‘museum’ collection) who also happens to be an ex-felon for several charges of grand larceny and bail jumping, and the other is known for being a voracious Wikipedia page editor, and not much else. And much like any spokesperson, neither of them do anything without a price tag attached to it. For all their 7+ years of writing that book, they’ve already announced their plans to re-write huge sections of the book (they would need to basically start over, since there’s no fixing it), and their willingness to accept anybody’s offer to help them with that (I guess that’s where you come in?). So the 2nd edition will apparently be a ‘group’ effort, much like a Wikipedia page, and we all know how unreliable that site is for information. And to top it off, they had the gall to slap a $45 price tag on 800 pages of bad writing, poor photos, and questionable information.

“As a final note, I jsut want to point out that Zap has been pretty thoroughly discredited by modern video game history research.”

Not everybody, just Vendel and Goldberg, who’ve also attempted to discredit pretty much every other book on the subject, not to mention attack anybody who dares to question them. They want everyone to believe their book is the ‘final word’ on the subject. It’s not. Rather, it’s the final word on their career as authors, or at least it should be…

Alex Smith

November 7, 2014 at 6:04 am

Well Scott, that was a surprising and completely unwarranted personal attack, but okay, I’ll rejoin with a little civil discussion.

I don’t work with Marty or Curt on any projects, although I have communicated with Marty in the past via email. I don’t really know where you got that idea from. You won’t find my name sharing a byline with them anywhere, nor see me in any special thank you section. The most you will find is some comment exchanges on my blog.

For the record, I agree with Jimmy on pretty much all his points regarding Business is Fun: it is an impenetrable mess with no authorial voice and jumbled anecdotes. It also happens to be largely accurate (though not always, I think that in the effort to tell Ted Dabney’s story, for instance, they have marginalized Bushnell too much) and contains a great deal of information on Atari R&D projects based on internal documents and interviews. Therefore, I stand by my statement that it is the best source of information on R&D activities at the company. I never claimed any wider utility than that in my previous comment.

As for Zap, I will also agree with you that Marty and Curt have discredited that book more than they should: the primary source quotes are quite useful and I have found that some of what Marty and Curt have claimed to be false within the book has proven to be accurate. It does have flaws, however, particularly in the early portions, which are largely based on discussions with Bushnell only and not other early employees like Alcorn and Dabney, and last chapter, which contains nothing but speculation about the financial problems at the company in 1982. Incidentally, the best source for these problems is not Curt and Marty’s book, which is fairly weak on the business side of things, but rather Master of the Game, a biography of Steven Ross.

And yes, company spokesman sales figures can be exaggerated, which is why I also quoted the 300,000 figure from the Bernstein report, which is lower. I also referenced the chart from the IEEE article, which I speculated was hovering around that same 300,000 mark seeing as how the chart does not report exact figures. I also said that the 50,000 difference between your claim and Bernstein is pretty immaterial to the case (and if you had bothered to read my whole post, you would have seen that I linked to the IEEE article as well). The fact is, we do not have a reliable source for sales figures in 1977, just a range, which is what I articulated if you bothered to read everything I wrote.

Anyway, I admire Marty and Curt’s work on their book, even if the final result is flawed, and I agree with you that they get too defensive in forums and sometimes don’t admit when someone else has just as good information as they do (and Curt gets downright insulting much of the time, which I find unprofessional). I also admire the work on your site and the many interviews you have conducted with Atari alumni, which represents an important primary source on the period.

Anyway, I am just a scholar hunting down facts and trying to paint as accurate a picture as possible of video game history with the (unfortunately) limited and contradictory sources available. I don’t really have an ax to grind with anyone as you seem to, so in the future kindly leave me (and Jimmy’s comments section) out of any personal feuds you have with Messrs. Goldberg and Vendel.

Scott S

October 8, 2017 at 3:00 pm

Just posting the current link to my magazine archive:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/archives/magazines/magazines.html

Jim Levy

March 18, 2016 at 5:48 pm

Greg had become president of Activision International after first serving as a consultant to me on international deals and licensing. He did indeed bring in the Ghostbuster deal based on his relationship with a friend at Columbia Pictures. Even though Activision had not engaged in licensed products before that, there never was a strict “prohibition” of same. In the beginning, we didn’t have the money to license so relied on the creative ability of our artists/designers to produce what was broadly recognized as superior games, and, by the time we did have the money, our designers had strong reputations of their own that became like “brands” for each new game. BTW, the success of Ghostbusters in the UK and beyond was very important to the company after the collapse of the US market and while both the industry and Activision were rebuilding in 1984-86.

Chad

October 8, 2019 at 8:52 pm

If only more CEO’s had similar vision and morals to Jim Levy… I will never understand why people can’t find a healthy compromise between profit margin and delivering products their customers deserve…

Denis Hickey

January 9, 2020 at 6:38 pm

Jim, where are you? You can locate me by looking up “denis hickey, author,” or send me an email. My address: shache1@aol.comdenis

Lisa H.

November 5, 2014 at 9:37 pm

I never had Designer’s Pencil, but I loved playing around with KoalaPainter.

Web Dimension reminds me a little of the much, much later (PS2) Rez.

Scott S.

November 6, 2014 at 2:24 pm

Atari sold some 250,000 VCS consoles in 1977, and 750,000 the following year: http://www.2600connection.com/faq/vcs_system/faq_atarivcs.html#hardware1

VCS Pac-Man was not under any time constraints (like E.T. was). That’s an old rumor without any source to back it up.

Atari had plans for holography in the form of the Cosmos. My interview with Roger Hector covers this in detail: http://www.2600connection.com/interviews/roger_hector/interview_roger_hector.html

As you noted, Warner initially drastically cut Atari’s R&D, but they still poured countless millions into R&D over the years, but for all time and money spent, they had nothing to show for it. The ‘mass exodus’ of Atari’s engineers wasn’t’ because Atari spent too little on R&D, it was because they never released anything that R&D developed. The home systems Atari had developed or were developing by the time Bushnell left were the same systems they had by the time Warner sold the company in 1984. All that was released under Kassar were repackaged versions.

Also, Little Computer People was not exactly an original title of Activision’s. It was originally developed by James Wickstead Design Associates under the name Pet Person. Activision bought it, made some changes, and released it as LCP.

Jimmy Maher

November 6, 2014 at 3:04 pm

Thanks for providing a source on those figures! It seems to be the “tens of thousands” business which is bothering people, and which may not read to mean quite like what I meant it to mean. :) So, nixed that.

On the subject of the engineering exodus, I’m just a little bit confused about how the timeline could work if they were leaving out of frustration over products not being *released*. The exodus I’m speaking of was the one in 1979-1980. At this time Atari *was* releasing new products, in the form of the very impressive Atari 400 and 800. There may very well have been later exits born of other frustrations — I’m very certain you know much more about all this than me — but I think Kassar’s initial R&D cuts almost had to be the main motivation in the period we’re discussing.

On the subject of Little Computer People, I don’t think we’re doing justice to Crane and Activision in just saying they “made some changes and released it,” even if that is technically correct in the broadest possible strokes. The Pet Person concept had no interactivity to it, for example; it was a sort of virtual fishbowl. Crane describes Activision as buying the project only as a “starting point.” Anyway, the question of whether or not Activision *developed” LCP in-house all by their lonesome isn’t hugely relevant; Shanghai and Web Dimension, for example, were the products of outside developers. The larger point here is that Levy and his colleagues had the vision to take a chance on *publishing* so many innovative creations.

Keith Smith

November 7, 2014 at 11:29 pm

One source I’m surprised no one has mentioned for 1977 VCS sales figures is Warner’s 1977 annual report, which states “Atari enjoyed major successes and significant disappointments in its consumer division during 1977. The company’s produce line, led by the programmable Video Computer System, was extremely well received by the trade and by September the company had orders for all the games it could manufacture. However, as the year wore on, it became clear that suppliers of semiconductors (“chips”) would not meet delivery schedules. Despite this, Atari sold some 850,000 games, of which roughly 40% were Video Computer Systems.” That would put 1977 VCS sales (Warner’s fiscal year ended December 31) at somewhere in the neighborhood of 340,000 if the figures are accurate. Of course, they could be inaccurate, but it seems that Warner would be taking a big risk by reporting inaccurate numbers in its annual report (IIRC in the early 1980s, part of the reason they got into legal hot water was because they had merely made overly optimistic statements in their annual report..

Keith Smith

November 7, 2014 at 11:30 pm

oh, and that should be “product line” not “produce line” (Atari didn’t make veggies that I know of)

Scott S.

December 29, 2014 at 12:49 am

Here’s my interview with former JWDA designer Todd Marshall, who worked on Pet Person (aka Little Computer People):

http://www.2600connection.com/interviews/todd_marshall/interview_todd_marshall.html

Scott S

October 8, 2017 at 3:06 pm

Updated link to my interview with Todd Marshall:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/archives/interviews/todd_marshall/interview_todd_marshall.html

… and a new interview I did with Dennis Koble, who helped prove more info from the “Atari Business is Fun book is incorrect:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/archives/interviews/dennis_koble/interview_dennis_koble.html

Jim Levy

March 18, 2016 at 5:52 pm

” It was originally developed by James Wickstead Design Associates under the name Pet Person. Activision bought it, made some changes, and released it as LCP.”

We bought this concept at a pretty raw stage. The lion’s share of what you see in the final product was conceived and developed by Crane and his team. The concept of Little Computer People living in your PC actually was developed by our marketing team and me, working with David and the designers, and one of my fondest memories of that time is the creation of the packaging for the product, a comic-like tabloid newspaper announcing the discovery of LCP.

Scott Stilphen

April 21, 2017 at 2:51 am

Todd Marshall states a team of at least 4 people worked on Pet Person extensively for a year before JWDA sold it to Activision. Not sure how ‘raw’ it was when it was sold. Would be nice if a copy of Pet Person were archived and made available.

Scott S

October 8, 2017 at 3:03 pm

Just updating the links from my previous post:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/faq/faq.html#hardware1

.. and the earliest ad for the VCS, priced at $169.88:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/faq/faq.html#general1

Roger Hector interview:

http://www.ataricompendium.com/archives/interviews/roger_hector/interview_roger_hector.html

David Boddie

November 6, 2014 at 4:04 pm

You’re missing an easy link to River Raid. :-)

David Boddie

November 6, 2014 at 4:05 pm

Of course, now I see that it was linked to earlier in the article…

Brandon Campbell

November 6, 2014 at 8:50 pm

I loved Little Computer People! Mine was named Steve, and later on I downloaded a utility off Q-Link that let me save my LCP so another one could move in, and switch between the different ones. But what I really wanted was more than one person in the house at the same time, which I finally got in The Sims many years later. GameMaker was also pretty cool, and I think I would have really enjoyed Designer’s Pencil.

Carl

November 7, 2014 at 5:01 am

You wonder aloud if the Activision IPO was the best or worst timing and you indicate several millionaires were made. Sadly, when a company goes public employees with stock options typically aren’t allowed to sell them for some time. This happened with Activision, so the IPO was not good timing for the worker bees.

Here’s a really interesting interview with Carol Shaw that mentions this briefly.

Carl

November 7, 2014 at 5:02 am

couldn’t get the tag to work right. Here’s the address:

http://www.vintagecomputing.com/index.php/archives/800/vcg-interview-carol-shaw-female-video-game-pioneer-2

Steven Weyhrich

November 8, 2014 at 4:54 pm

Another fascinating article that goes into the background of what was happening with game software in the 1980s! Thanks!

Brian Bagnall

November 11, 2014 at 1:50 am

Nice article! I once interviewed Gary Kitchen for my old fansite here:

http://www.mts.net/~kbagnall/commodore/gamemaker/info.html

He gave some wonderful answers as I recall, and then I promptly lost the interview. It still bums me out to this day, and through the years I have tried to find that interview only to come up empty handed each time.

Garry Kitchen

March 2, 2017 at 6:40 am

Brian,

If you’d like to redo the interview, reach out to me at http://www.garrykitchen.com.

Best,

Garry Kitchen

DZ-Jay

March 6, 2017 at 12:04 pm

I loved, loved, loved Ghostbusters on the C=64. I must have played that introduction song over and over for hours, singing along and just had it play in the background while I did homework. I really liked the movie (and it is still one of my favourite movies of all time) and as I child in 1984, I found the game’s play mechanics a great adaptation of the movie’s plot. After all, the entire premise of the movie is founded on a bunch of enterprising scientists getting out of academia and starting their own business. Plus, it was just a lot of fun, with a good mixture of strategy and action.

Then there’s Hacker. I have a romantic fascination with that game as a concept. Boy, I was deeply infatuated with the idea of Hacker: to stumble upon the mystery and intrigue of WarGames or Cloak & Dagger, and having only your wits and curiosity to help you figure things out. I loved that, and as a matter of fact, enjoyed every second of the initial “hacking” sequence of the game many, many times over.

However, once you get past the introduction and enter the game proper, the game feels very derivative and the entire mystique of the starting story fizzles out into just another Carmen Sandiego type of game. As you say, it feels very anticlimactic. I never managed to get deep enough into it to finish it, although I tried every so often to give it another go. I just couldn’t get past the clichéd and disappointing game-play that followed such an intriguing and clever starting phase.

Anyway, thank you for the memories. I would have liked to see you take a deeper dive into these two games which left a rather big mark on the gaming scene, if not for what they were on their own, but for what they represented at the time.

Regards,

-dZ.

Jason Kankiewicz

August 21, 2017 at 5:24 am

“engineers and programmers that made them” -> “engineers and programmers who made them”?

“again place them” -> “again placed them”?

“many painful downsizes” -> “many painful downsizings”?

“the dimension door” -> “the dimensional door”?

“to “innovate!” Some” -> “to “innovate!”. Some”?

“Like _Deus Ex Machina_ not” -> “Like _Deus Ex Machina_, not”?

“all becomes anticlimax” -> “all becomes anticlimactic”?

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2017 at 9:38 am

Thanks as always!

Gerry Fitzgerald

November 21, 2019 at 7:45 pm

Just happened upon Jimmy Maher’s November 5 2014 article on Activision and Jim Levy. I had the good fortune to work for Activision from 1983-1984. From my perspective (I was a recruiter in HR) it was a magical place to work, thanks in no small part to Jim Levy. I wish everyone the opportunity to experience loving their job and the people they work with–Jim created this environment.

Jerri Kohl

April 21, 2020 at 7:27 pm

So your conjecture is that the Space Invaders craze of the 2nd half of 1978 (which wasn’t as much of a craze in NA as in Japan) translated into increased VCS sales due to a resultant general raised interest in playing video games? I could see that, but never considered the effect of SI on the VCS until the cartridge was released in Jan 1980 (which was the year when my parents bought me a VCS–with SI and other games). How much of the 1978 sales increase would you attribute to this vs the other reasons?

Jimmy Maher

April 21, 2020 at 7:41 pm

Sorry, but I’m just not the best person to get into the weeds on things like this. The early console scene really isn’t my specialty.

Jonathan O

May 30, 2021 at 7:36 am

Another very late possible typo: when you said “… plenty of stolid action games…” did you mean to say “solid”?

Jimmy Maher

June 1, 2021 at 12:20 pm

Thanks!

Davide

February 2, 2022 at 11:26 pm

Great article as ever; just to let you know, the original idea of LCP is due to a developer named Rich Gold; Crane just developed it

Ben

April 4, 2022 at 4:37 pm

law suits -> lawsuits

play book -> playbook

Jimmy Maher

April 6, 2022 at 8:18 am

Thanks!