Games were everywhere at Infocom. By that I mean all sorts of games, not just interactive fiction — although even the latter existed in more varieties than you might expect, such as an interactive live-action play where the audience shouted out instructions to the actors, to be filtered through and interpreted by a “parser” played by one Dave Lebling. Readers of The New Zork Times thrilled to the exploits of Infocom’s softball team in a league that also included such software stars as Lotus and Spinnaker. There were the hermit-crab races held at “Drink’em Downs” right there at CambridgePark Drive. (I had a Lance Armstrong-like moment of disillusionment in scouring Jason Scott’s Get Lamp tapes for these articles when habitual winner Mike Dornbrook revealed the sordid secret to his success: he had in fact been juicing his crabs all along by running hot water over his little cold-blooded entrants before races.) And of course every reader of The New Zork Times was also familiar with Infocom’s collective love for puzzles — word, logic, trivia, or uncategorizable — removed from any semblance of fiction, interactive or otherwise. And then there was the collective passion for traditional board and card games of all stripes, often played with a downright disconcerting intensity. Innocent office Uno matches soon turned into “bloody” tournaments. One cold Boston winter a Diplomacy campaign got so serious and sparked such discord amongst the cabin-fever-addled participants that the normally equanimous Jon Palace finally stepped in and banned the game from the premises. Perhaps the most perennial of all the games was a networked multiplayer version of Boggle that much of the office played almost every day at close of business. Steve Meretzky got so good, and could type so fast, that he could enter a word and win a round before the other players had even begun to mentally process the letters before them.

Given this love for games as well as the creativity of so many at Infocom, it was inevitable that they would also start making up their own games that had nothing to do with prose or parsers. Indeed, little home-grown ludic experiments were everywhere, appropriating whatever materials were to hand; Andrew Kaluzniacki recalls Meretzky once making up a game on the fly that used only a stack of business cards lying on the desk before him. Most of these creations lived and died inside the Infocom offices, but an interesting congruence of circumstances allowed one of them to escape to the outside world as Fooblitzky, Infocom’s one game that definitely can’t be labelled an interactive fiction or adventure game and thus (along with, if you like, Cornerstone) the great anomaly in their catalog.

We’ve already seen many times that technology often dictates design. That’s even truer in the case of Fooblitzky than in most. Its origins date back to early 1984, when Mike Berlyn, fresh off of Infidel, was put in charge of one of Infocom’s several big technology initiatives for the year: a cross-platform system for writing and delivering graphical games to stand along the one already in place for text adventures and in development for business products.

It was by far the thorniest proposition of the three, one that had already been rejected in favor of pure text adventures and an iconic anti-graphics advertising campaign more than a year earlier when Infocom had walked away from a potential partnership with Penguin Software, “The Graphics People.” As I described in an earlier article, Infocom’s development methodology, built as it was around their DEC minicomputer, was just not well suited to graphics. It’s not quite accurate to say, however, that the DEC terminals necessarily could only display text. By now DEC had begun selling terminals like the VT125 with bitmap graphics capabilities, which could be programmed using a library called ReGIS. This, it seemed, might just open a window of possibility for coding graphical games on the DEC.

Still, the DEC represented only one end of the pipeline; they also needed to deliver the finished product on microcomputers. Trying to create a graphical Z-Machine would, again, be much more complicated than its text-only equivalent. To run an Infocom text adventure, a computer needed only be capable of displaying text for output and of accepting text for input. Excepting only a few ultra-low-end models, virtually any disk-drive-equipped computer available for purchase in 1984 could do the job; some might display more text onscreen, or do it more or less attractively or quickly, but all of them could do it. Yet the same computers differed enormously in their graphics capabilities. Some, like the old TRS-80, had virtually none to speak of; some, like the IBM PC and the Apple II, were fairly rudimentary in this area; some, like the Atari 800 and the Commodore 64 and even the IBM PCjr, could do surprisingly impressive things in the hands of a skilled programmer. All of these machines ran at different screen resolutions, with different color palettes, with different sets of fiddly restrictions on what color any given pixel could be. Infocom would be forced to choose a lowest common denominator to target, then sacrifice yet more speed and capability to the need to run any would-be game through an interpreter. Suffice to say that such a system wasn’t likely to challenge, say, Epyx when it came to slick and beautiful action games. But then maybe that was just as well: even the DEC graphical terminals hadn’t been designed with videogames in mind but rather static “business graphics” — i.e., charts and graphs and the like — and weren’t likely to reveal heretofore unknown abilities for running something like Summer Games.

But in spite of it all some thought that Infocom might be able to do certain types of games tolerably well with such a system. Andrew Kaluzniacki, a major technical contributor to the cross-platform graphics project:

It was pretty obvious pretty quickly that we couldn’t do complicated real-time graphics like you might see in an arcade game. But you could do a board game. You could lay the board out in a way that would look sufficiently similar across platforms, that would look acceptable.

Thus was the multiplayer board/computer game hybrid Fooblitzky born almost as a proof of concept — or perhaps a justification for the work that had already been put into the cross-platform graphics system.

Fooblitzky and the graphics system itself, both operating as essentially a single project under Mike Berlyn, soon monopolized the time of several people amongst the minority of the staff not working on Cornerstone. Kaluzniacki, a new hire in Dan Horn’s Micro Group, wrote a graphics editor for the Apple II which was used by a pair of artists, Brian Cody and Paula Maxwell, to draw the pictures. These were then transferred to the DEC for incorporation into the game; the technology on that side was the usual joint effort by the old guard of DEC-centric Imps. The mastermind on the interpreter side was another of Horn’s stars, Poh C. Lim, almost universally known as “Magic” Lim due to his fondness for inscrutable “magic numbers” in his code marked off with a big “Don’t touch this!” Berlyn, with considerable assistance from Marc Blank, took the role of principal game designer as well as project manager.

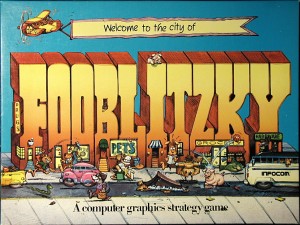

Fooblitzky may have been born as largely “something to do with our graphics system,” but Infocom wasn’t given to doing anything halfway. Berlyn worked long and hard on the design, putting far more passion into it than he had into either of his last two interactive-fiction works. The artists also worked to make the game as pleasing and charming as it could be given the restrictions under which they labored. And finally the whole was given that most essential prerequisite to any good game of any type: seemingly endless rounds of play-testing and tweaking. Fooblitzky tournaments became a fixture of life at Infocom for a time, often pitting the divisions of the company against one another. (Business Products surprisingly proved very competitive with Consumer Products; poor Jon Palace “set the record for playing Fooblitzky more times and losing more times than anyone else in the universe.”) When the time came to create the packaging, Infocom did their usual superlative, hyper-creative job. Fooblitzky came with a set of markers and little dry-erase boards, one for each of the up to four players, for taking notes and making plans, along with not one but two manuals — the full rules and a “Bare Essentials” quick-start guide, the presence of which makes the game sound much more complicated than it actually is — and the inevitable feelie, which as in the Cornerstone package here took the form of a button.

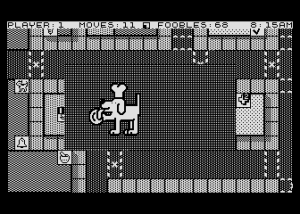

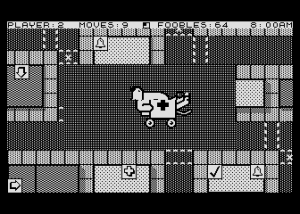

Fooblitzky is a game of deduction, one more entry in a long and ongoing tradition in board and casual gaming. At the beginning of a game, each player secretly chooses one of a possible eighteen items. If fewer than four are playing — two to four players are possible — the computer then randomly (and secretly) picks enough items to round out the total to four. Players then take turns moving about a game board representing the town of Fooblitzky, trying to deduce what the three initially unidentified items are and gather a full set together. The first to bring all four items back to a “check point” wins.

Items start out in stores which are scattered about the board. Also present are pawn shops in which items can be sold and bought; restaurants in which you can work to earn money if you deplete your initial store; crosswalks which can randomly lead to unintended contact with traffic and an expensive stay in the hospital; phone booths for calling distant stores and checking stock; storage lockers for stashing items (you can only carry four with you, a brutal inventory limit indeed); even a subway that can whisk you around the board quickly — for, as with most things in Fooblitzky, a price. Adding a layer of chaos over the proceedings is the Chance Man, who appears randomly from time to time to do something good, like giving you a free item, or bad, like dropping a piano on your head and sending you to the hospital. By making use of all of the above and more, while also watching everything everyone else does, players try to figure out the correct items and get them collected and delivered before their rivals; thus the need for the note-taking boards.

Once you get the hang of the game, which doesn’t take long, a lot of possibilities open up for strategy and even a little devious psychology. Bluffing becomes a viable option: cast off that correct item in a pawn shop as if it’s incorrect, then watch your opponents race off down the wrong track while you do the rest of what you need to do before you buy it back, carry it to the check point, and win. If you prefer to be less passive aggressive and more, well, active aggressive, you can just run into an opponent in the street to scatter her items everywhere and try to grab what you need.

It can all be a lot of fun, although I’m not sure I can label Fooblitzky a classic. There just seems to be something missing — what, I can’t quite put my finger on — for me to go that far. One problem is that some games are much more interesting than others — granted, a complaint that could be applied to just about any game, but the variation seems much more pronounced here than it ought to. By far the best game of Fooblitzky I’ve ever played was one involving just my wife Dorte and me. By chance three of the four needed items turned out to be the same, leading to a mad, confused scramble that lasted at least twice as long as a normal game, as we each thought we’d figured out the solution several times only to get our collection rejected. (Dorte finally won in the end, as usual.) That game was really exciting. By contrast, however, the more typical game in which all four items are distinct can start to seem almost rote after just a few sessions in quick succession; even deviousness can only add so much to the equation. If Fooblitzky was a board game, I tend to think it’d be one you’d dust off once or twice a year, not a game-night perennial.

That said, Fooblitzky‘s presentation is every bit as whimsical and cute as it wants to be. Each player’s avatar is a little dog because, well, why not? My favorite bit of all is the dish-washing graphic.

Cute as it is, Fooblitzky and the cross-platform project which spawned it weren’t universally loved within Infocom. Far from it. Mike Berlyn characterizes the debate over just what to do with Fooblitzky as a “bitter battle.” Mike Dornbrook’s marketing department, already dealing with the confusion over just why Infocom was releasing something like Cornerstone, was deeply concerned about further “brand dilution” if this erstwhile interactive-fiction company now suddenly released something like Fooblitzky.

The obvious riposte to such concerns would have been to make Fooblitzky so compelling, such an obvious moneyspinner, that it simply had to be released and promoted heavily. But in truth Fooblitzky was far from that. Its very description — that of a light social game — made it an horrifically hard sell in the 1980s, as evidenced by the relative commercial failure of even better games like my beloved M.U.L.E. Like much of Electronic Arts’s early catalog, it was targeted at a certain demographic of more relaxed, casual computer gaming that never quite emerged in sufficient numbers from the home-computing boom and bust. And Fooblitzky‘s graphics, while perhaps better than what anyone had any right to expect, are still slow and limited. A few luddites at Infocom may have been wedded to the notion of the company as a maker of only pure-text games, but for many more the problem was not that Fooblitzky had graphics but rather that the graphics just weren’t good enough for the Infocom stamp of quality. They would have preferred to find a way to do cross-platform graphics right, but there was no money for such a project in the wake of Cornerstone. Fooblitzky‘s graphics had been produced on a relative shoestring, and unfortunately they kind of looked it. Some naysayers pointedly suggest that if it wasn’t possible to do a computerized Fooblitzky right they should just remove the computer from the equation entirely and make a pure board game out of it (the branding confusion that would have resulted from that would have truly given Dornbrook and company nightmares!).

And so Fooblitzky languished for months even after Mike Berlyn left the company and the cross-platform-graphics project as a whole fell victim to the InfoAusterity program. Interpreters were only created for the IBM PC, Apple II, and Atari 8-bit line, notably leaving the biggest game machine in the world, the Commodore 64, unsupported. At last in September of 1985 Infocom started selling it exclusively via mail order to members of the established family — i.e., readers of The New Zork Times. Marketing finally relented and started shipping the game to stores the following spring where, what with their virtually nonexistent efforts at promotion, it sold in predictably tiny quantities: well under 10,000 copies in total.

The whole Fooblitzky saga is the story of a confused company with muddled priorities creating something that didn’t quite fit anywhere and never really had a chance. Like Cornerstone’s complicated virtual machine, the cross-platform graphics initiative ended up being technically masterful but more damaging than useful to the finished product. Infocom could have had a much slicker game for much less money had they simply written the thing on a microcomputer and then ported it to the two or three other really popular and graphically viable platforms by hand. Infocom’s old “We hate micros!” slogan, their determination to funnel everything through the big DEC, was becoming increasingly damaging to them in a rapidly changing computing world, their biggest traditional strength threatening to become a huge liability. Even by 1984 the big DECSystem-20 was starting to look a bit antiquated to those who knew where computing was going. In just a few more years, when Infocom would junk the DEC at last, it would literally be junked: the big fleet of red refrigerators, worth a cool million dollars when it came to Infocom in 1982, was effectively worthless barely five years later, a relic of a bygone era.

Because Fooblitzky is such an oddity with none of the name recognition or lingering commercial value of the more traditional Infocom games, I’m going to break my usual pattern and offer it for download here in its Atari 8-bit configuration. It’s still good for an evening or two’s scavenging fun with friends or family. Next time we’ll get back to interactive fiction proper and dig into one of the most important games Infocom ever released.

(Just the usual suspects as sources this time around: Jason Scott’s Get Lamp interviews and my collection of New Zork Times issues.)

Jason Scott

April 23, 2014 at 4:06 pm

I have the moment where Dornbrook reveals the juiced crabs cheat to Dave Lebling and Stu Galley on video. It’s a precious moment.

Not Fenimore

September 11, 2020 at 12:11 am

I wasn’t able to find this on the Internet Archive dump – is it up there? Which interview video is it under? I’d definitely love to see that.

Andrew Schultz

April 23, 2014 at 7:40 pm

Poh C. Lim, almost universally known as “Magic” Lim due to his fondness for inscrutable “magic numbers” in his code

This line made me laugh, which is hard to do. I never considered the nickname ‘Magic’ could be ironic.

I’ve never really played Foobilitzky–since it requires >1 person to be really fun, so I’m glad to read this.

Jason Kankiewicz

February 7, 2017 at 2:20 am

“Foobliztky” -> “Fooblitzky”?

Jimmy Maher

February 7, 2017 at 9:53 am

Thanks!

Mike Taylor

March 22, 2018 at 3:15 pm

Players then take turns moving about a game board representing the town of Fooblitzky, trying to deduce what the three initially unidentified items are and gather a full set together. The first to bring all four items back to a “check point” wins.

In other words …

In this Adventure you’re to find *TREASURES* & store them away.

Sign “Leave *TREASURES* here, then say: SCORE”

:-)

Havoc Crow

December 12, 2023 at 5:21 pm

This sure is some crazy box art, but my favorite part is the cheeky fish, who is just… casually levitating down the street with a big grin.

_RGTech

February 5, 2024 at 5:44 pm

Is “Readers of The New Zork Times thrilled to the exploits of Infocom’s softball team” missing a verb (“were thrilled”), or is my english not good enough to read this sentence without stumbling?

arcanetrivia

February 5, 2024 at 8:59 pm

“Thrill to [something]” is a correct usage. It means to experience a wave of emotion or excitement caused by the thing. Similar to “were thrilled by”, but an active construction instead of a passive one. The place I most immediately think of it being used is in old movie trailers that invite the audience to “Thrill to…” the sight of whatever supposedly exciting thing is going to happen in the film.