When Robert Botch joined Automated Simulations as director of marketing just as 1982 expired, it wasn’t exactly the sexiest company in the industry. They were still flogging their Dunjonquest line, which now consisted of no less than eleven sequels, spinoffs, and expansions to Temple of Apshai. More than a year after co-founder Jon Freeman had left in frustration over partner Jim Connelley’s refusal to update Automated’s technology, the entire line was still derived from the same BASIC-based engine that had first been designed to run on a 16 K TRS-80 back in 1979. It was hard for anyone to articulate why someone would choose to play a Dunjonquest game in a world that contained Ultima and Wizardry. And, indeed, Automated’s sales numbers were not looking very good, and the company had stopped making money almost from the moment that the Ultima and Wizardry series debuted. Still, that hadn’t prevented them from benefiting from the torrents of venture capital that entered the young industry in 1982, courtesy of the pundits who were billing home computers as the next big thing to succeed the game consoles. But now the investors were getting worried, wondering if this stodgy company and their somewhat pedantic approach to gaming had really been such a good risk after all. Thus Botch, whom Connelley hired under pressure to remake Automated’s image.

Botch’s first assignment was to visit the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas that January, with Dunjonquest titles in tow to display to the crowd on a big-screen television rented for the occasion. Botch, who knew nothing about computers or computer games, didn’t much understand the Dunjonquest concept. He could hardly be blamed, for just trying to figure out which one you could play was confusing as hell: you needed to already have Temple of Apshai to play these additional games, but needed Hellfire Warrior to play those, etc. He was therefore relieved when another employee handed him a disk containing a straightforward, standalone action/puzzle game for the Atari home-computer line called Jumpman, a sort of massively expanded version of the arcade classic Donkey Kong with thirty levels to explore. Unusually for Automated, who usually developed games in-house, its presence was the result of an unsolicited third-party submission from a hacker named Randy Glover.

Botch was such a computer novice that he couldn’t figure out how to boot the game; his colleague had to tell him to “put it in that little slot over by the computer.” But when he finally got it working he fell in love. The rest of the show turned into an extended battle of wills between Botch and Connelley. The latter, who was determined to showcase the Dunjonquest games, would “come over, yell a lot, and tell me to take the disk out. Whenever he left the room, I’d load the program in again.” The crowd seemed to agree with Botch: he left CES with a notebook full of orders for the as yet unreleased Jumpman, convinced that in it he had seen the only viable future for his new employers.

The embattled Connelley saw his power further eroded the following month, when the investors brought in Michael Katz, an unsentimental, hard-driving businessman with an eye for mainstream appeal. He had spent the past four years at Coleco, where he had masterminded the launch of some very successful handheld electronic games as well as the ColecoVision console, which had just sold more than 500,000 units in its first Christmas on the market. It was first agreed that Connelley and Katz would co-lead the company, but this was obviously impractical and untenable. In a scenario that could have easily happened to Ken Williams at Sierra if he had been less strong-willed and business-savvy, Connelley was being eased out of his own company by the monied interests he had welcomed with open arms. Seeing which way the wind was blowing, he left within months, taking a number of his loyalists with him to form a development studio he named The Connelley Group, which would release a couple of games through Automated before becoming free agents and eventually fading away quietly.

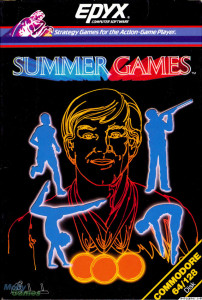

Katz, Botch, and the other newcomers were thus left alone to literally transform Automated Simulations into a new company. Automated had for some time now been branding many of their games with the label of “Epyx,” arrived at because their first choice, “Epic,” was already taken by a record label. No matter; “Epyx” was a better name anyway, proof that even a blind-to-PR squirrel like Connelley could find a nut every now and again. Katz and Botch now made it the official name of the reborn company, excising all trace of the stodgy old “Automated Simulations” name. Gone also would be the nerdy old Dunjonquest line which positively reeked of Dungeons and Dragons sessions in parents’ basements. They would instead strive to make Epyx synonymous with colorful, accessible games like Jumpman, aimed straight at the heart of the mass market. The old slogan of “Computer Games Thinkers Play” now became “Strategy Games for the Action-Game Player,” and they hired Chiat Day, Apple’s PR firm and the hottest such in Silicon Valley, to remake Epyx’s image entirely.

Jumpman itself made a good start toward that goal. It was a huge hit, especially once ported to the Commodore 64. One of the first games to really take proper advantage of the 64’s audiovisual capabilities, it hit that platform like a nova at mid-year, topping the sales charts for months and probably becoming the bestselling single Commodore 64 game of 1983. It alone was enough to return Epyx to profitability. Unsurprisingly given commercial returns like that, from now on Epyx would develop first and most for the 64. They also hired Glover to work in-house. Before the end of the year he had already delivered a cartridge-based pseudo-sequel, Jumpman Junior, to reach ultra-low-end systems without a disk drive.

But now Katz had a problem. Other than Glover, he lacked the technical staff to make the Jumpmans of the future. Most of them had left with Connelley — and anyway games like their old Dunjonquests were exactly what the new Epyx didn’t want to be making. Then Starpath caught Katz’s eye.

Back in 1981, two former Atari engineers, Bob Brown and Craig Nelson, had founded Arcadia, Inc., eventually to be renamed Starpath after the release of the Arcadia 2001, an ill-conceived and short-lived games console from Emerson Radio Corporation. Drawing from friends, family, and former colleagues, Brown and Nelson put together a crack team of hardware and software hackers to make their mark in the Atari VCS market. Their flagship product was the marvelously Rube Goldberg-esque Supercharger, which plugged into the VCS’s cartridge port and added 6 K of memory (which may not sound like much until you remember that the VCS shipped with all of 128 bytes), new graphics routines in ROM, and a cable to connect the console to a cassette player. Starpath developed and released half a dozen games on cassette for use with the Supercharger, most of them apparently quite impressive indeed. But problems dogged Starpath. The company lived in constant fear of legal action by Atari, whom Brown and Nelson had not left on particularly good terms, in response to their unauthorized expansion. It did eventually become clear that Starpath had little to fear from Atari, but for the worst possible reason: the videogame market was collapsing, and Atari had far bigger problems than little Starpath. By late 1983 Starpath was floundering. Katz swooped, buying the entire company for a song and moving them lock, stock, and barrel from Santa Clara, California, into Epyx’s headquarters in nearby Sunnyvale.

Katz had no interest in any of Starpath’s extant products for a dead Atari VCS market. No, he wanted the programming talent and creative flair that had led to the Supercharger and its games in the first place. If they could do work like that on the Atari VCS, imagine what they could do with a Commodore 64. The Starpath folks would prove to be the final, most essential piece in his remaking of Epyx.

One of Starpath’s programmers, Dennis Caswell, had been playing around with ideas for a platforming action-adventure game before the acquisition. Indeed, he was already at work trying to animate the running man who would be the star. It was decided to let Caswell, who had three Supercharger games under his belt, run with his idea on the Commodore 64. He says his elation at the platform change was so great that “I unplugged my [Atari] 2600 and threw it out of my office and into the hall.” Working essentially alone, Caswell crafted one of the iconic Commodore 64 games and one of the bestselling in the history of Epyx: Impossible Mission.

Starpath had also been working on a decathlon simulation. In fact, it was far enough along to be basically playable. They discussed porting it to the 64, but the capabilities of that machine quickly led them to think about something more than just a simulation of track and field. Why not use the luxury of 64 K of memory and disk-based storage to simulate a broader cross-section of Summer Olympic events? With the 1984 Summer Olympics coming to Los Angeles, it seemed the perfect game for the zeitgeist, with exactly the sort of mass-market appeal Katz wanted from his new titles. He thought it a brilliant idea, and even went so far as to approach the Olympic Committee about making it an officially licensed product. He found, however, that Atari had long before sewn up the rights, back when they had been the fastest growing company in America. Epyx therefore decided to do everything possible to associate the game with the Olympics without outright declaring it to be an official Olympics simulation. They pushed the envelope pretty far: the game would be called Summer Games, would begin with an opening ceremony and a runner lighting a flame to the strains of “Bugler’s Dream,” would offer medals, would (as its advertising copy proclaimed) let you “go for the gold!” representing the country of your choice. Such legal boundary-pushing became something of a habit; witness Impossible Mission, which plainly hoped to benefit from an association with Mission: Impossible. (This in spite of the fact that Scott Adams had already been forced by the lawyers to change the name of his third adventure from Mission Impossible to Secret Mission.) In the case of Summer Games, Epyx likely got away with it because Atari was in no financial shape to press the issue and the Olympic Committee, never the most progressive institution, was barely aware of home-computer games’ existence. To this day many people are shocked to realize that Summer Games is not actually an official Olympics game. It all speaks to Katz’s determination to create games that felt up-to-date and relevant to the times. Yes, sometimes that could backfire, leading to trying-way-too-hard titles like Break Dance. Much of the time, however, it was commercial gold.

The original design brief for Summer Games called for ten events. The team also very much wished to include head-to-head, real-time competition wherever the nature of the sport being simulated allowed it. Beyond that, they would pretty much make it up on the fly; even the events themselves were largely chosen in the moment. The Starpath programmers’ talents were augmented by Randy Glover of Jumpman fame and Epyx’s first full-time artist, Erin Murphy. They were all under the gun from the start, for Katz wanted them to have something ready to show at the 1984 Winter CES, barely six weeks away when the project was officially green-lit. They worked through the holidays to deliver. Epyx arrived at CES with a very impressive albeit non-interactive opening-ceremonies sequence, fairly playable 4 X 400-meter relay and 100-meter dash races (both partially adapted from Starpath’s old decathlon project), and a diving event. At the show they learned that they had more competition in the (pseudo-)Olympics genre beyond Atari. HESWare, an aggressive up-and-comer not that dissimilar to Epyx who were about to sign Leonard Nimoy as their spokesman, showed HES Games. The prospect pushed Epyx to make sure Summer Games both met its planned pre-Summer Olympics release date and was as good as they could make it. To help with the former, the original plan for ten events was reduced to eight, principally via the sacrifice of weight lifting (fans of which sport would have to wait until 1986’s World Games to get their due). To help with the latter, more resources and personnel were poured into the project.

Even as this happened, attrition, a constant at Epyx, also became a concern. Katz’s new Epyx could be a rewarding place, but also an unrelentingly intense and competitive one, full of mathematical athletes convinced they were the smartest people in the room and all too happy to demonstrate it at their rivals’ expense. The spirit of competition extended beyond working hours; hundreds of dollars changed hands weekly in epic games of poker. Even some of Epyx’s brightest stars eventually found the company’s testosterone- and brainpower-fueled culture too much to take. Thus Starpath co-founder Bob Brown, finding Starpath’s new masters not to his liking, left quite soon after the acquisition, and Randy Glover, who had been assigned to the swimming events, abruptly left not long after CES. The swimming events were taken up by Stephen Landrum, the biggest single contributor to the project as a whole, who also did the opening ceremonies and the diving and pole-vaulting events.

It had been decided early on that Summer Games would let you compete as the representative of any of a variety of nations, complete with flags and national anthems to play during the medal ceremonies. Since it obviously would not be possible to include all of the 140 countries who would participate in the real Olympics, Epyx was left with the question of which ones should make the cut. Beyond the big, obvious powerhouses of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, commercial considerations once again reigned supreme here. Katz had begun signing deals with foreign distributors, pushing hard to get Epyx’s games into the vibrant British and steadily emerging Western European software markets. Epyx reasoned that players in these countries would want the opportunity to represent their own nation. Thus relative Summer-Olympic non-factors like Norway and Denmark were included in the game, while potent teams from parts of the world that didn’t buy computer games, like East Germany, Romania, and Yugoslavia, were omitted. Most of the countries included had never been visited by anyone at Epyx. They sourced the flag designs from a world atlas, and called consulates and sales connections in Europe to drum up sheet music for the various anthems. Many of those anthems had never been heard by anyone working on the game; if some sound a bit “off” in tone or tempo, perhaps that’s the reason. For the coup de grâce, Epyx couldn’t resist including their own company as one of the “nations,” complete with a national anthem that was actually the Jumpman theme.

Summer Games was nearing the final crunch time on May 8, 1984, when the Soviet Union initiated a boycott of the Los Angeles Games in a rather petty quid pro quo for the West’s boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games. (The people who were really hurt by both gestures were not the governments of the boycottees but a generation of athletes on both sides of the political divide, who lost what was for many literally a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to compete against the true best of their peers on the biggest stage their sports could offer them.) Epyx quickly decided to leave the Soviet Union in their version of the Olympics. After the game’s release, they reached out a bit cheekily to the Soviets in real life. Botch:

We sent the Russian [read: Soviet] embassy (in Washington, D.C.) several copies of Summer Games for the Commodore 64. An enclosed letter stated since they would not be competing in the regular Olympics, at least they could participate in our version of the Games. This package was eventually returned to us with a thank-you note, because they only had access to Atari home computers. Our marketing people quickly replaced the Commodore software with Atari material and sent it back. I always wondered if they enjoyed the game, because we never heard from them again.

Epyx’s bigger concern was the same as that of everyone involved with the Los Angeles Games, whether directly or tangentially: what commercial impact would the boycott have? It seemed it must inevitably tarnish the Games’ luster somewhat. In the case of both Summer Games and the Olympic Games themselves, the impact would turn out to be less than expected. The latter has gone down in history as the most financially successful Olympics of modern times, while Summer Games would become — and this probably comes as anything but a spoiler to most of you — one of the bestselling computer games of the year, and the first entry of the bestselling series in the history of the Commodore 64.

Katz was determined to get Summer Games out in June, to beat HES Games to the market and to derive maximum advantage from the pre-Olympics media buildup. The team worked frantically to finish the final two events (gymnastics and skeet shooting) and swat bugs. They worked all but straight through the final 72 hours. Disks went into production right on schedule, the morning after the code they contained had been finalized.

Summer Games went on to sell in the hundreds of thousands across North America and Europe, thoroughly overshadowing the less impressive Olympian efforts of HESWare and Atari, the latter of whose games were at any rate only available on their own faltering lines of game consoles and home computers. It would be ported to a variety of platforms, although it would always remain at its best on the Commodore 64. Together with Impossible Mission and a racing game developed by the indefatigable Landrum and Caswell called Pitstop II, both also huge worldwide smashes, Summer Games completed the remaking of Epyx’s image and made of them a worldwide commercial powerhouse. Being for the most part conceptually simple games without much dependence on text, most of Epyx’s games were ideally suited to do well in non-English-speaking countries. Combined with Katz’s aggressive distributional push, this was key to making Epyx one of the first big entertainment-software publishers that could be said to be truly international. With so many potential customers to serve in emerging new markets and several new hits in addition to the still popular Jumpman, sales in 1984 soared as Epyx enjoyed almost exponential growth in earnings as the months passed.

We’ll continue the story of Epyx later, but for now I’m not quite done with Summer Games. Next time I’d like to do something I haven’t done in a while: dig into the technology a bit and explain how some of the magic that wowed so many back in 1984 actually works. It will also give us a chance to get to know the Commodore 64, a computer whose importance to gaming during the middle years of the 1980s can hardly be overstated, just a little bit better.

(The bulk of this article is drawn from two lengthy retrospectives published in the July 1988 and August 1989 issues of Commodore Magazine. The pictures of Randy Glover comes from the April 1984 K-Power.)

sean barrett

August 4, 2013 at 3:01 pm

There’s extra characters at the end of the link to the archon page that breaks it (at least in Firefox).

Jimmy Maher

August 4, 2013 at 4:02 pm

Weird. Upgrading to WordPress 3.6 seems to have broken links all through the database by inserting garbage characters after the final “/”. I think I fixed it with an SQL search and replace.

Thanks!

fan and ghost editor

August 4, 2013 at 6:02 pm

pundents? pundits?

ZUrlocker

August 4, 2013 at 10:18 pm

I think you mean “pundit” rather than “pundent” in para 1. Otherwise, a good post on the origins of Epyx.

–Z

Jimmy Maher

August 5, 2013 at 5:26 am

Thanks!

Tale

August 5, 2013 at 9:18 am

Aw, I was hoping for the nifty playable game versions of Summer Games and Jumpman, like in earlier articles.

Apart from that, well done! (As always).

Jimmy Maher

August 5, 2013 at 9:25 am

There’s still one post to go on Summer Games, so don’t despair. ;)

Mike Whalen

August 5, 2013 at 7:57 pm

Outstanding work as always, Jimmy, and I am very much looking forward to the next post!!

Rob

August 6, 2013 at 4:49 am

On the subject of national anthems sounding a bit “off”, the Australian national anthem featured in the Epyx Games series was actually “Waltzing Matilda”, an Australian folk song. To be fair it is often seen as our unofficial anthem, but sounds nothing like the official “Advance Australia Fair”.

Gilles Duchesne

August 8, 2013 at 5:18 am

Aw, and up to this very day I thought that the Australian anthem was also the theme from that “Secret Valley” TV show… :-(

Pierre

August 7, 2013 at 2:50 pm

Superb! About a month ago I came across an old Atari joystick that I played Jumpman with. Then a few days latter I found a Pitstop II cart for the C64 along with an Epyx branded joystick (500XJ). That’s when I thought, “what ever happened to Epyx?” I did a little search but the results weren’t satisfying.

Jimmy, thanks for filling a blank in my mind. Looking forward to the next few posts.

Oh and I loved your Amiga book. The best in the series by far.

Scott

August 15, 2013 at 12:54 am

Love the blog Jimmy, just one note on this one – while technically correct I think “metals” in paragraph 10 should be “medals” :)

Jimmy Maher

August 15, 2013 at 7:11 am

Thanks!

Kent Purrington

October 1, 2014 at 5:27 am

I was one of the playtesters at Epyx during this time. I would love to touch base with any of the programers of the time from Starpath or Mr. Botch, to say thanks for some fun years with a computer. Thanks for filling in some holes in my knowledge of Epyx.

Jeffvv53

September 16, 2015 at 12:54 am

You can’t beat the old games. I remember shelling out $60 for Ultima 3 for the C64. Having a $300 phone bill because I played Zork over the phone

Kevin Savetz

August 18, 2016 at 3:19 pm

My 2016 interview with Randy Glover is here: http://ataripodcast.libsyn.com/antic-interview-171-randy-glover-jumpman

Paulette Johnson

June 20, 2017 at 10:34 pm

Where and how can I get the game Jumpman you made in 1986

I would really like to play the game Jumpman

Or how can I get in contact with Randy Glover

Thank you for your halo

Paulette Johnson

Br. Bill

January 29, 2018 at 12:01 am

This is not a huge deal, because many alternatives can be easily found, but the link to the YouTube video demonstrating “Bugler’s Dream” no longer works.

Jimmy Maher

January 29, 2018 at 6:06 pm

Thanks! Replaced with one of those many alternatives. ;)

Ben Bilgri

February 25, 2018 at 10:25 pm

“far enough along” > “far enough long”

“May, 8, 1984” – extra comma

“Soviets in real life. Blotch:” – Should be Botch?

“It will also give us a chance” > “It was also give us a chance”

Jimmy Maher

February 26, 2018 at 4:16 pm

Thanks!

Jonathan O

December 28, 2020 at 10:37 pm

A bit late, I know, but:

“Even some of Epyx’s brightest stars eventually found the company’s testoserone-and brainpower-fueled culture” – should be “…testosterone- and brainpower…”

Jimmy Maher

December 29, 2020 at 3:41 pm

Thanks!

Ben

March 20, 2021 at 6:28 pm

hard-driving businessmen -> hard-driving businessman

One of first -> One of the first

boycotees -> boycottees

Jimmy Maher

April 18, 2021 at 10:33 am

Thanks!