As we learned in the earlier articles in this series, Interplay celebrated the Christmas of 1997 with two new CRPGs. One of them, the striking post-apocalyptic exercise called Fallout, was greeted with largely rave reviews. The other, of course, was the far less well-received licensed Dungeons & Dragons game called Descent to Undermountain. The company intended to repeat the pattern in 1998, with another Fallout and another Dungeons & Dragons game. This time, however, the public’s reception of the two efforts would be nearly the polar opposite of last time.

It’s perhaps indicative of the muddled nature of the project that Interplay couldn’t come up with any plot-relevant subtitle for Fallout 2. It’s just another “Post-Nuclear Role-Playing Game.”

Tim Cain claims that he never gave much of a thought to any sequels to Fallout during the three and a half years he spent working on the first game. Brian Fargo, on the other hand, started to think “franchise” as soon as he woke up to Fallout’s commercial potential circa the summer of 1997. Fallout 2 was added to Interplay’s list of active projects a couple of months before the original game even shipped.

Interplay’s sorry shape as a business made the idea of a quick sequel even more appealing than it might otherwise have been. For it should be possible to do it relatively cheaply; the engine and the core rules were already built. It would just be a matter of generating a new story and design, ones that would reuse as many audiovisual assets as possible.

Yet Fargo was not pleased by the initial design proposals that reached his desk. So, just days after Fallout 1 had shipped, he asked Tim Cain to get together with his principal partners Leonard Boyarsky and Jason Anderson and come up with a proposal of their own for the sequel. The three were dismayed by this request; exhausted as they were by months of crunch on Fallout 1, they had anticipated enjoying a relaxing holiday season, not jumping right back into the fray on Fallout 2. Their proposal reflected their mental exhaustion. It spring-boarded off of a joking aside in the original game’s manual, a satirical advertisement which Jason Anderson had drawn up in an afternoon when he was told by Interplay’s printer that there would be an unsightly blank page in the booklet as matters currently stood. The result was the “Garden of Eden Creation Kit”: “When all clear sounds on your radio, you don’t want to be caught without one!” Elaborating on this thin shred of a premise, the sequel would cast you as a descendant of the star of the first game, sent out into the dangerous wastelands to recover one of these Garden of Eden Kits in lieu of a water chip. This apple did not fall far from the tree.

But as it turned out, that suited Brian Fargo just fine. Within a month of Fallout 1′s release, Cain, Boyarsky, and Anderson had been officially assigned to the Fallout 2 project. None of them was terribly happy about it; what all three of them really wanted were a break, a bonus check, and the chance to work on something else, roughly in that order of priority. In January of 1998, feeling under-appreciated and physically incapable of withstanding the solid ten months of crunch that he knew lay before him, Cain turned in his resignation. Boyarsky and Anderson quit the same day in a show of solidarity. (The three would go on to found Troika Studios, whose games we will be meeting in future articles on this site, God willing and the creek don’t rise.)

Following their exodus, Fallout 2 fell to Feargus Urquhart and the rest of his new Black Isle CRPG division to turn into a finished product. Actually, to use the word “division” is to badly overstate Black Isle’s degree of separation from the rest of Interplay. Black Isle was more a marketing label and a polite fiction than a lived reality; the boundaries between it and the mother ship were, shall we say, rather porous. Employees tended to drift back and forth across the border without anyone much noticing.

This was certainly the case for most of those who worked on Fallout 2, a group which came to encompass about a third of the company at one time or another. Returning to the development approach that had yielded Wasteland a decade earlier, Fargo and Urquhart parceled the game out to whoever they thought might have the time to contribute a piece of it. Designer and writer Chris Avellone, who was drafted onto the Fallout 2 team for a few months while he was supposed to be working on another forthcoming CRPG called Planescape: Torment, has little positive to say about the experience: “I do feel like the heart of the team had gone. And all that was left were a bunch of developers working on different aspects of the game like a big patchwork beast. But there wasn’t a good spine or heart to the game. We were just making content as fast as we could. Fallout 2 was a slapdash product without a lot of oversight.”

Still, the programmers did fix some of what annoyed me about Fallout 1, by cleaning up some of the countless little niggles in the interface. Companions were reworked, such that they now behave more or less as you’d expect: they’re no longer so likely to shoot you in the back, are happy to trade items with you, and don’t force you to kill them just to get around them in narrow spaces. Although the game as a whole still strikes me as more clunky and cumbersome than it needs to be — the turn-based combat system is as molasses-slow as ever — the developers clearly did make an effort to unkink as many bottlenecks as they could in the time they had.

But sadly, Fallout 2 is a case of one step forward, one step back: although it’s a modestly smoother-playing game, it lacks its predecessor’s thematic clarity and unified aesthetic vision. Its world is one of disparate parts, slapped together with no rhyme, reason, or editorial oversight. It wants to be funny — always the last resort of a game that lacks the courage of its fictional convictions — but it doesn’t have any surfeit of true wit to hand. It tries to make up for the deficit the same way as many a game of this era, by transgressing boundaries of taste and throwing out lazy references to other pop culture as a substitute for making up its own jokes. This game is very nerdy male, very adolescent-to-twenty-something, and very late 1990s — so much so that anyone who didn’t live through that period as part of the same clique will have trouble figuring out what it’s on about much of the time. I do understand most of the spaghetti it throws at the walls — lucky me! — but that doesn’t keep me from finding it fairly insufferable.

Fallout 2 shipped in October of 1998, just when it was supposed to. But its reception in the gaming press was noticeably more muted than that of its predecessor. Reviewers found it hard to overlook the bugs and glitches that were everywhere, the inevitable result of its rushed and chaotic development cycle, even as the more discerning among them made note of the jarring change in tone and the lack of overall cohesion to the story and design. The game under-performed expectations commercially as well, spending only one week in the American top ten. In the aftermath, Brian Fargo’s would-be CRPG franchise looked like it had already run its course; no serious plans for a Fallout 3 would be mooted at Interplay for quite some time to come.

Yet Fallout 2 did do Interplay’s other big CRPG for that Christmas an ironic service. When BioWare told Fargo that they would like a couple of extra months to finish Baldur’s Gate up properly, the prospect of another Interplay CRPG on store shelves that October made it easier for him to grant their request. So, instead of taking full advantage of the Christmas buying season, Baldur’s Gate didn’t finally ship until a scant four days before the holiday. Never mind: the decision not to ship it before its time paid dividends that some quantity of ephemeral Christmas sales could never have matched. Plenty of gamers proved ready to hand over their holiday cash and gift cards in the days right after Christmas for the most hotly anticipated Dungeons & Dragons computer game since Pool of Radiance. Baldur’s Gate sold 175,000 units before 1998 was over. (Just to put that figure in perspective, this was more copies than Fallout 1 had sold in fifteen months.) Its sales figures would go on to top 1 million units in less than a year, making it the bestselling CRPG to date that wasn’t named Diablo. The cover provided by Fallout 2 helped to ensure that Dr. Muzyka and Dr. Zeschuk would never have to see another patient again.

I’m not someone who places a great deal of sentimental value on physical things. But despite my lack of pack-rattery, some bits of flotsam from my early years have managed to follow me through countless changes of address on both sides of a very big ocean. Playing Baldur’s Gate prompted me to rummage around in the storage room until I came up with one of them. It goes by the name of In Search of Adventure. This rather generically titled little book is, as it says on the front cover, a “campaign adventure” for tabletop Dungeons & Dragons. Note the absence of the “Advanced” prefix; this adventure is for the non-advanced version of the game, the one that was sold in those iconic red and blue boxes that conquered the cafeteria lunch tables of Middle America during the first few years of the 1980s, when TSR dared to dream that their flagship game might become the next Monopoly. If we’re being honest, I always preferred to play this version of the game even after its heyday passed away. It seemed to me more easy-going, more fun-focused, less stuffily, pedantically Gygaxian.

Anyway, the campaign adventure in question came out in 1987, well after my preferred version of Dungeons & Dragons had become the weak sister to its advanced, hardcore sibling — unsurprisingly so, given that pretty much the only people still playing the game by that point were hardcore by definition.

In Search of Adventure is actually a compilation of nine earlier adventure modules that TSR published for beginning-level characters, crammed together into one book with a new stub of a plot to serve as a connecting tissue. I dug it out of storage and have proceeded to talk about it here because it reminds me inordinately of Baldur’s Gate, which works on exactly the same set of principles. There’s an overarching story to it, sure, but it too is mostly just a big grab bag of geography to explore and monsters to fight, in whatever order you prefer. In this sense and many others, it’s defiantly traditionalist. It has more to do with Dungeons & Dragons as it was played around those aforementioned school lunch tables than it does with the avant-garde posturings of TSR’s latter days. As I noted in my last article, the Forgotten Realms in which Baldur’s Gate is set — and in which In Search of Adventure might as well be set, for all that it matters — is so appealing to players precisely because it’s so uninterested in challenging them. The Forgotten Realms is the archetypal place to play Dungeons & Dragons. Likewise, Baldur’s Gate is an archetypal Dungeons & Dragons computer game, the essence of the “a group of adventurers meet in a bar…” school of role-playing. (You really do meet some of your most important companions in Baldur’s Gate in a bar…)

Luke Kristjanson, the BioWare writer responsible for most of the dialog in Baldur’s Gate, says that he never saw the computer game as “a simulation of a fully-realized Medieval world”: “It was a simulation of playing [tabletop] Dungeons & Dragons.” This statement is, I think, the key to understanding where BioWare was coming from and what still makes their game so appealing today, more than a quarter-century on.

Opening with a Nietzsche quote leads one to fear that Baldur’s Gate is going to try to punch way, way above its weight. Thankfully, it gets the pretentiousness out of its system early and settles down to meat-and-potatoes fare. BioWare’s intention was never, says Luke Kristjanson, to make “a serious fantasy for serious people.” Thank God for that!

But here’s the brilliant twist: in order to conjure up the spirit of those cafeteria gatherings of yore, Baldur’s Gate uses every affordance of late-1990s computer technology that it can lay its hands on. It wants to give you that 1980s vibe, but it wants to do it better — more painlessly, more intuitively, more prettily — than any computer of that decade could possibly have managed. Call it neoclassical digital Dungeons & Dragons.

The game begins in a walled cloister known as Candlekeep, which has a bit of a Name of the Rose vibe, being full of monks who have dedicated their lives to gathering and preserving the world’s knowledge. The character you play is an orphan who has grown up in Candlekeep as the ward of a kindly mage named Gorion. This bucolic opening act gives you the opportunity to learn the ropes, via a tutorial and a few simple, low-stakes quests. But soon enough, a fearsome figure in armor shatters the peace of the cloister, killing Gorion and forcing you to take to the road in search of adventure (to coin a phrase). The game does suggest at the outset that you visit a certain tavern where you might find some useful companions, but it never insists that you do this or anything else. Instead you’re allowed to go wherever you want and to do exactly that thing which pleases you most once you get there. When you do achieve milestones in the main plot, whether deliberately or inadvertently, they’re heralded with onscreen chapter breaks which demonstrate that the story is progressing, because of or despite your antics. In this way, the game tries to create a balance between player freedom and the equally bracing sense of being caught up in an epic plot, one in which you will come to play the pivotal role — being, as you eventually learn, the “Chosen One” who has been marked by destiny. Have I mentioned that Baldur’s Gate is not a game that shirks from fantasy clichés?

Of course, there’s an unavoidable tension between the set-piece plot of the chapter-based structure and the open-world aspect of the game — a tension which we’ve encountered in other games I’ve written about. The main plot is constantly urging you forward, insisting that the fate of the world is at stake and time is of the essence. Meanwhile the many side quests are asking you to rescue a lost housecat or collect wolf pelts for a merchant. If you take the game at its word and rush forward with a sense of urgency, you’ll not only come to the climax under-leveled but will have missed most of the fun. All of which is to say that Baldur’s Gate is best approached like that In Search of Adventure module: just start walking around. Go see what is to be found in those parts of your map that are still blank. Sooner or later, you’ll trigger the next chunk of the main plot anyway.

It’s amazing how enduring some of what is to be found in those blank spaces has proved. My wife likes to read graphic novels. I was surprised recently to see that she’d started on a Dungeons & Dragons-branded one called Days of Endless Adventure, with a copyright date of 2021. I was even more surprised when I flipped it open idly and came face to face with the simple-minded ranger Minsc and his precious pet hamster Boo, both of whom were introduced to the world in Baldur’s Gate.

A congenital visual blurriness dogs this game, the result of a little bit too much detail being crammed into a relatively low resolution of 640 X 480, combined with a subdued, brown- and gray-heavy color palette. My middle-aged eyes weren’t always so happy about it, especially when I played on a television in the living room.

As it happened, I had had quite a time with Minsc when I played the game. He joined my party fairly early on, on the condition that we would try to rescue his friend, a magic user named Dynaheir who was being imprisoned in a gnoll stronghold. Unfortunately, I applied the same logic to his principal desire that I did to the main quest line; I’d get to it when I got to it. I maintained this attitude even as he nagged me about it with increasing urgency. One day the dude just flipped out on me, went nuts and started to attack me and my other companions. What’s a person to do in such a situation? Reader, I killed him and his pet hamster.

I was playing a ranger myself, so I didn’t think losing his services would be any big problem. I didn’t notice until days later that killing him — even though, I rush to stipulate again, he attacked me first — had turned me into a “fallen ranger.” I’m told by people who know about such things that this is far from ideal, because it means that you’ve essentially been reduced to the status of a vanilla fighter, albeit one who craves a lot more experience points than usual to advance a level. Oh, well. I didn’t feel like going back so many hours, and I was in more of a “roll with the punches” than a “try and try again” frame of mind anyway. (I’m also told that there will be a way to reverse my fallen condition when I get around to playing Baldur’s Gate II with the same party. So that’s something to look forward to, I guess.) By way of completing the black comedy, I later did rescue Dynaheir and took her into my party. But I was careful not to mention that I had ever met her mysteriously vanished friend…

Any given play-through of Baldur’s Gate is guaranteed to generate dozens of such anecdotes, which combine to make its story your story, even if the text of the chapter breaks is the same for everyone. You don’t have to walk on eggshells, afraid that you’re going to break some necessary piece of plot machinery. Again, it’s you who gets to choose where you go, what you do there, and who travels with you on your quest. Any mistake you make along the way that doesn’t get you and all your friends killed can generally be recovered from or at least lived with, as I did my fallen-ranger status. Tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, says Luke Kristjanson, is about “[being with] your friends [and] doing something fun. And occasionally one’s a jackass and does something weird and you roll with it.” It does seem to me that rolling with it is the only good way to play this second-order simulation of that social experience.

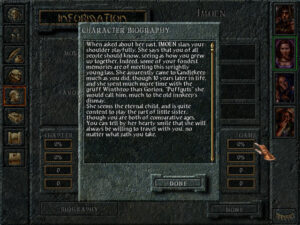

The first companion to join you will probably be Imoen, a spunky female thief. The personalities of your companions are all firmly archetypal, but most of them are likeable enough that it’s hard to complain. Sometimes fantasy comfort food goes down just fine.

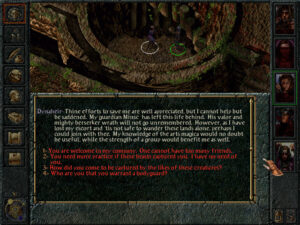

Baldur’s Gate’s specific methods of presenting its world of freedom and opportunity have proved as influential as the design philosophies that undergird it. The Infinity Engine provided the presentational blueprint for a whole school of CRPGs that are still with us to this day. You look down on the environment and the characters in it from a free-scrolling isometric point of view. You can move the “camera” anywhere you like in the current area, independent of the locations of your characters. That said, a fog-of-war is implemented: places your characters have not yet seen are completely blacked out, and you can’t know what other people or monsters are getting up to if they’re out of your characters’ line of sight.

The interface proper surrounds this view on three sides. Portraits of the members of your party — up to five of them, in addition to the character you create and embody from the outset — run down the right side of the screen. Command icons — some pertaining to the individual party members and some to the group as a whole or to the computer on which you’re running the game — stretch across the left side and bottom of the screen. An area just above the bottom line of icons can expand to display text, of which there is an awful lot in this game, mostly in the form of menu-driven conversations. (In 1998, we were still far from the era when it would be practical and cost-effective to have full voice-acting in a game with this much yammering. Instead just the occasional line of dialog is voiced, to establish personalities and set tones.) The interface is perhaps a bit more obscure and initially daunting than it might be in a modern game, but the contrast with the old keyboard-driven SSI Gold Box games could hardly be more stark. And thankfully, unlike Fallout’s, Baldur’s Gate’s interface doesn’t make the mistake of prioritizing aesthetics over utility.

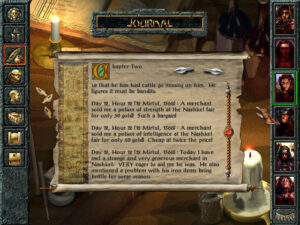

In short, Baldur’s Gate tries really, really hard to be approachable in the way that modern players have come to expect, even if it doesn’t always make it all the way there. Take, for instance, its journal, an exhaustive chronicle of the personal story that you are generating as you play. That’s great. But what’s less great is that it can be inordinately difficult to sift through the huge mass of text to find the details of a quest you’re pretty sure you accepted sometime last week. Most of us would love to have a simple bullet list of quests to go along with the verbose diary, however much that may cause the hardcore immersion-seekers to howl in protest at the gameyness of it all. Later Infinity Engine games corrected oversights like this one.

The most oft-discussed and controversial aspect of the Infinity Engine, back in the day and to some extent even today, is its implementation of combat. As we’ve learned, makers of CRPGs in the late 1990s faced a real conundrum when it came to combat. They wanted to preserve a measure of tactical complexity, but they also had to reckon with the reality of a marketplace that showed a clear preference for fast-paced, fluid gameplay over turn-based models. Fallout tried to square that circle by running in real-time until a fight began, at which point it forced you back into a turn-based framework; Might and Magic VI did a little better in my opinion by letting you decide when you wanted to go turn-based. In a way, BioWare was even more constrained than the designers of either of those two games, because they were explicitly making a digital implementation of a turn-based set of tabletop rules.

Their solution to the conundrum was real-time-with-pause, in which the computer automatically acts out the combat, adhering to the rules of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons but, critically, without advertising the breaks between rounds and turns. The player can assert her will at any point in the proceedings by tapping the space bar to pause the action, issuing new commands to her charges, and then tapping it again to let the battle resume.

Clever though the scheme is, not everyone loves it. And, to be sure, there are valid complaints to levy against it. Big fights can all too quickly degenerate into a blob of intersecting sprites, with spells going off everywhere and everyone screaming at once; it’s like watching twenty Tasmanian Devils — the Looney Tunes version, that is — in a fur-flying free-for-all. Yet there are ways to alleviate the confusion by making judicious use of the option to “auto-pause,” a hugely important capability that is mentioned only in oblique passing in the game’s 160-page manual, presumably because that document was sent to the printing press before the software it described had been finalized. Auto-pause will let you stop the action automatically whenever certain conditions of your choice are met — or even at the end of every single action taken by every single member of your party, if you choose to go that far. Doing so lets you effectively turn Baldur’s Gate into a purely turn-based game, if that’s your preference. Or you can go fully turn-based only for the really big fights that you know will require careful micro-management. This is what I do. The rest of the time, I just use a few judicious break points — a character is critically wounded, a spell caster has finished casting a spell, etc. — and otherwise rely on the good old space bar.

Another option — the best one for those most determined to turn the game into a simulation of playing tabletop Dungeons & Dragons with your mates — is to turn on artificial intelligence for every member of your party but the one you created. Then you just let them all do their things while you do yours. You may find yourself less enamored with this approach, however, after you become part of the collateral damage of one of Dynaheir’s Fireball spells for the first time. (Shades of the stone-stupid and deadly companions in Fallout…)

Baldur’s Gate’s combat definitely isn’t perfect, but in its day it was a good-faith attempt to deliver an experience that was recognizably Dungeons & Dragons while also catering to the demands of the contemporary marketplace. I think it holds up okay today, especially when placed in the context of the rest of the game that houses it, which has ambitions for its world and its fiction that transcend the tactical-combat simulations that the latter-day Gold Box games especially lapsed into. It is true that your companions’ artificial intelligence could be better, as it is true that it’s sometimes harder than it ought to be to figure out what’s really going on, a byproduct of graphics that are somewhat muddy even at the best of times and of having way too many character sprites in way too small a space. But your fighters, who don’t usually require too much micro-management, are the most affected by this latter problem, while your spell casters ought to be standing well back from the fray anyway, if they know what’s good for them. Another not-terrible approach, then, is to control your spell casters yourself, since they’re the ones who can most easily ruin their companions’ day, and leave your fighters to their own devices. But you’ll doubtless figure out what works best for you within the first few hours.

Indeed, Baldur’s Gate feels disarmingly modern in the way that it bends over backward to adjust itself to your preferred style of play. This encompasses not only the myriad of auto-pause and artificial-intelligence options but an adjustable global difficulty slider for combat. All of this allows you to breeze through the fights with minimal effort or hunker down for a long series of intricate tactical struggles, just as you choose. Giving your player as many ways to play as possible is seldom a bad choice in commercial game design. Not everyone had yet figured that out in the late 1990s.

If you want the ultimate simulation of playing tabletop Dungeons & Dragons with your friends, you can turn on an option to watch the actual die rolls scrolling past during combat.

BioWare and Interplay released an expansion pack to Baldur’s Gate called Tales of the Sword Coast just six months after the base game. Rather than serving as a sequel to the main plot, it’s content merely to add some new ancillary areas to explore betwixt and between fulfilling your destiny as The Chosen One. Given that I definitely don’t consider the main plot the most interesting part of Baldur’s Gate, I have no problem with this approach in theory. Nevertheless, the expansion pack strikes me as underwhelming and kind of superfluous — like a collection of all the leftover bits that failed to make the cut the first time around, which I suspect is exactly what it is. The biggest addition is an elaborate dungeon known as Durlag’s Tower, created to partially address one of the principal ironies of the base game: the fact that it contains surprisingly little in the way of dungeons and no dragons whatsoever. The latter failing would have to wait for the proper sequel to be corrected, but BioWare did try to shore up the former aspect by presenting an old-school, tactically complex dungeon crawl of the sort that Gary Gygax would have loved, a maze rife not only with tough monsters but with secret doors, illusions, traps, and all manner of other subtle trickery. Personally, I tend to find this sort of thing more tedious than exciting at this stage of my life, at least when it’s implemented in this particular game engine. I decided pretty quickly after venturing inside to let old Durlag keep his tower, since he seemed to be having a much better time there than I was.

Durlag’s Tower. The Infinity Engine doesn’t do so well in such narrow, trap-filled spaces. It’s hard to keep your characters from blundering into places that they shouldn’t.

While your reaction to the über-dungeon may be a matter of taste, a more objective ground for concern is all of the new sources of experience points the expansion adds, whilst raising the experience and level caps on your characters only modestly. As a result, it becomes that much easier to max out your characters before you finish the game, a state of affairs which is no fun at all. In my eyes, then, Baldur’s Gate is a better, tighter game without the expansion. For better or for worse, though, Tales of the Sword Coast has become impossible to extricate from the base game, being automatically incorporated into all of the modern downloadable editions. So, I’ll content myself with telling you to feel free to skip Durlag’s Tower and/or any of the other additional content if it’s not your thing. There’s nothing essential to the rest of the game to be found there.

Whatever its infelicities and niggles, it’s almost impossible to overstate the importance and influence of Baldur’s Gate in the broader context of gaming history. Forget the comparisons I’ve been making again and again in these articles to Pool of Radiance: one can actually make a case for Baldur’s Gate as the most important single-player CRPG released between 1981, the landmark year of the first Wizardry and Ultima, and the date of this very article that you’re reading.

Baldur’s Gate’s unprecedented level of commercial success transformed the intersection between tabletop Dungeons & Dragons and its digital incarnations from a one-way avenue into a two-way street; all of the future editions of the tabletop rules that would emerge under Wizards of the Coast’s watch would be explicitly crafted with an eye to what worked on the computer as well. At the same time, Baldur’s Gate cemented one of the more enduring abstract design templates in digital gaming history; witness the extraordinary success of 2023’s belated Baldur’s Gate 3. The CRPGs that more immediately followed Baldur’s Gate I, both those that were powered by the Infinity Engine and those that only borrowed some of its ideas, found ways to improve on the template in countless granular details, but they were all equally the heirs to this very first Infinity Engine game. Yes, Fallout got there first, and in some respects did it even better, with a less clichéd, more striking setting and an even deeper-seated commitment to acknowledging and responding to its player’s choices. And there’s more than a little something to be said for the role played by the goofy, janky, uninhibited Monty Haul fun of Might and Magic VI in the rehabilitation of the CRPG genre as well. Yet the fact remains that it was Baldur’s Gate that truly led the big, meaty CRPG out of the wilderness and back into the mainstream.

Then again, gaming history is not a zero-sum game. The note on which I’d prefer to end this series of articles is simply that the CRPG genre was back by 1999. Increasingly, it would be the computer games that drove sales of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons rather than the other way around. Meanwhile a whole lot of other CRPGs, including some of the most interesting ones of all, would be given permission to blaze their own trails without benefit of a license. I look forward to visiting or revisiting some of them with you in the years to come, as we explore this genre’s second golden age.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: For Baldur’s Gate, see my last article, with the addition of the book BioWare: Stories and Secrets from 25 Years of Game Development, which commenter Infinitron was kind enough to tell me about.

For Fallout 2: the book Beneath a Starless Sky: Pillars of Eternity and the Infinity Engine Era of RPGs by David L. Craddock. Computer Gaming World of February 1999; Retro Gamer 72 and 188. Also Chris Avellone’s appearance on Soren Johnson’s Designer Notes podcast and Tim Cain’s YouTube channel.

Where to Get Them: Fallout 2 and Baldur’s Gate are both available as digital purchases at GOG.com, the latter in an “enhanced edition” that sports some welcome quality-of-life improvements alongside some additional characters and quests that don’t sit as well with everyone. Note that it buying it does give you access to the original game as well.