The fifth season of The X-Files, spanning from 1997 to 1998, marked the absolute zenith of the show’s popularity, when it put up the best average ratings in its history. Everybody seemed to want a piece of its action; even William Gibson and Stephen King submitted scripts that season.

As we learned in an earlier article, The X-Files was always two shows in one. One show consisted of the “mythology” episodes: a heavily serialized, ever more convoluted tale of extraterrestrial interference in the affairs of humans and a myriad of conspiracies deriving therefrom, in which the stakes were, it had by now been revealed, positively apocalyptic in scope, involving alien plans to exterminate the human race and repopulate the planet with their own kind. The other show consisted of one-off “monster of the week” episodes, which were freer to go to unexpected places in terms of form and content and to not always take themselves so darn seriously. The hardcore X-Files fandom that had sustained the show through its first couple of seasons had been built on the back of the first type of episode, and this was still the type that got the most attention even in the glossy mainstream press. Yet there’s a strong critical consensus today — a consensus with which I heartily agree — that almost all of the most enduring episodes are actually of the “monster of the week” sort.

It was and is almost impossible to reconcile the coexistence of the two types of episode in the same fictional universe. Doing so demands that we accept that Mulder and Scully periodically decide to take a holiday from saving humanity from extinction in order to check up on rumors of Yet Another Freaky Serial Killer in Podunk, Idaho. The creators themselves were by no means unaware of the cognitive dissonance. One argument they deployed in response was a plea to treat Mulder and Scully like Superman, Nancy Drew, or Kirk and Spock had once been treated: as characters who simply have adventures in the abstract, without sweating the details of chronology. “Who knows in what order the fictional lives of Mulder and Scully take place?” said producer-director Rob Bowman. “We never said that that was week two and this is week three in their lives. We are just saying that this is episode two and this is episode three and it happened whenever.” Such hand-waving may have been thoroughly out of step with obsessive X-Files fandom, but it does indeed seem like the most satisfying way to approach the series today, not least because it allows us to appreciate the best of the standalone episodes as the little self-contained marvels they are.

I speak of episodes like Chris Carter’s own “The Post-Modern Prometheus,” whose name is a play on the subtitle of Mary Shelley’s classic novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. It’s a funny and sad retelling of that story, moved to twentieth-century small-town America and shot in stark black and white, the better to evoke the old monster movies from which the show drew so much inspiration. But it’s more than just an homage; the “postmodern” in the title is amply justified. The story is barreling along toward its inevitable tragic climax when Mulder decides that tragedy just won’t do. He demands to see the writer, who turns out to be a chubby teenager who’s drawing a comic book. And suddenly the entire gang — Mulder, Scully, the monster, and your stereotypical gaggle of pitchfork-wielding villagers, who were getting ready to string the last-named up from the nearest tree a minute earlier — are taking a road trip to see Cher, the monster’s favorite singer. She sings “Walking in Memphis,” his favorite song, and Mulder and Scully dance together with big smiles and glowing eyes while the monster shakes his booty right up there onstage. It’s weird and sweet and funny and yet still achingly sad at its core, and just thinking about it leaves me with a tear in my eye. I’ve just about decided that it’s my favorite episode of The X-Files ever. And it turns out that I’m in pretty good company there: both Chris Carter and David Duchovny have said the same.

Vince Gilligan’s “Bad Blood” is another standout from the fifth season. It has Mulder and Scully investigating an apparent vampire on the loose in a small Texas town — not exactly revolutionary subject matter for the show. Yet Gilligan turns the episode into a riff on Rashomon, letting us see the story from the points of view of both Mulder and Scully. For example, the sheriff of the town seen through Scully’s admiring eyes is the epitome of a handsome Southern gentleman, through Mulder’s jealous ones a bucktoothed hick. Once again, I find myself in good company in highlighting this episode. Gillian Anderson has named it as her own all-time favorite: “It was fun and challenging to film and even more fun to watch.”

The fifth-season finale led right into the big X-Files feature film, which had actually been shot almost a year before, during the break between the fourth and fifth seasons. It was a mythology episode blown up in length by a factor of about two and a half, and was neither notably better nor worse than that description would imply. The movie was perhaps most notable for existing at all; it was highly unusual to make a theatrical film set in the world of a television series that was still on the air. Chris Carter and Fox had been inspired by the success of Star Trek Generations, featuring the cast from Star Trek: The Next Generation, but that film and its sequels had come out only after the television series in question had wrapped for good. There was some thought that The X-Files too might transition into a purely cinematic franchise at some point, although it wasn’t clear when or how that might happen. “Hopefully,” said Gillian Anderson in an interview at the time, “the film will be so successful that the series will trail off and we’ll just be doing movies once in a while.”

Despite the limitations which its tight connection to the serialized mythology of the television show would seem to place on its mass appeal, the X-Files movie grossed $84 million in the United States alone, enough to make it the twentieth biggest film of the year there. All told, it was a solid performance, if not quite the gangbusters one that might have prompted Fox to think of turning The X-Files into a spectacle available exclusively on big rather than small screens sooner rather than later.

Even with all of its success, however, the show was navigating some logistical turbulence. David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson had both signed five-season contracts at the outset, and Duchovny wasn’t at all sure he wanted to renew his as the fifth season was winding down. He had aspirations of making the leap from television star to becoming a sought-after leading man in movies that weren’t named The X-Files, but this would be hard to do if he had to be off in Vancouver playing Mulder for all but a few months of every year. Further, he had just gotten married to the actress Téa Leoni, whose role on the sitcom The Naked Truth bound her to Hollywood. Duchovny gave Fox an ultimatum: he would join Gillian Anderson in signing a two-year contract extension if and only if the entire production was moved to Southern California.

It was a tough call — the move would make the show dramatically more expensive to produce each week — but nobody could imagine The X-Files without Mulder, and certainly nobody thought the show had run its course as of yet, not when it had just enjoyed its biggest season ever. So, Duchovny got his way. The folks who were working on the show in Vancouver were given a choice between relocation and severance packages. These dozens of people who had their lives so disrupted so that one man could have the arrangement that pleased him might be forgiven for concluding that David Duchovny was a self-entitled jerk. He didn’t do his reputation among them any more favors in the aftermath of the move, when he went around disparaging their hometown of Vancouver and its “400 inches of rain per day” in interviews on the talk-show circuit. But so be it; the show must go on.

The results of the move to California were evident from the first shot of the first episode of the sixth season: a desert landscape baking under a clear blue sky. That wasn’t the sort of shot you were ever going to get in Vancouver. The default tone of the show brightened in tandem with the sunshine quotient, prompting derision from some quarters of its hardcore fandom, who labeled this new Southern Californian incarnation “X-Files Lite.”

But these people do not speak for me. For all that I wouldn’t leap to defend David Duchovny from anyone who said he was a bit of a tool at this stage of his life, I’m afraid I can’t get behind those other criticisms. In fact, I’ll go way out on a limb and say that I like the sixth season the best of all of them, and that at least some of the seventh season isn’t that far behind it in my esteem. To my mind, the standalone episodes got warmer and wiser and smarter and funnier than they had ever been before. Granted, most continue to play with established mass-media archetypes. If not usually original in conception, though, they’re sly and clever in execution, with that good old Mulder and Scully charm and with more willingness than ever to stretch and bend the formal boundaries of the show. In their willingness to burrow deep into the universals of life and fate, I daresay that some of them remind me of nothing so much as the masterful short stories of Ted Chiang.

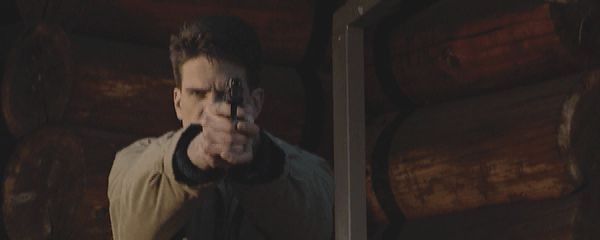

Vince Gilligan’s “Drive” opens with a helicopter’s eye view of a car chase that is obviously intended to evoke the O.J. Simpson Bronco chase over the highways of Los Angeles. Indeed, it initially presents itself as a special news broadcast that’s airing in place of your normally scheduled X-Files episode; these seasons do a lot of this sort of mucking about with credits sequences, etc., as if the fiction is escaping from the cage in which it is meant to be contained. The episode evolves into The X-Files’s take on the tautly wound 1994 film Speed. Here as there, the plot hinges on a vehicle that cannot stop if dire consequences are to be avoided. In this case, though, it’s Fox Mulder who’s behind the wheel, with a man behind him in the backseat who will die if he doesn’t keep moving. The reason why he will die may be down to the usual conspiratorial mumbo-jumbo, but that has little bearing on the propulsive problem at hand. This was arguably the first time The X-Files went full-on action movie — and, lo and behold, it does it rather brilliantly. (In a meta sense, “Drive” is also famous as the episode where Vince Gilligan first met Bryan Cranston, the man you see in the backseat above. Cranston would go on to become the star of Breaking Bad, Gilligan’s own acclaimed television show.)

At first glance, the most surprising thing about Chris Carter’s “Triangle” may seem to be that it took The X-Files this long to get around to doing an episode about the Bermuda Triangle. It was worth the wait. Defying a promise Carter made in the early days of the show to never fall down the wormhole of time-travel fiction, the script does indeed send Mulder back in time, to the first days of the Second World War, where he winds up aboard a passenger ship that’s about to be commandeered by some of its Nazi passengers. Doppelgängers of both Cancer Man and Scully are aboard, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. The important thing is that this gives William B. Davis the chance to try on an SS uniform that suits him to a tee, and gives Gillian Anderson the opportunity to try her hand at playing a hard-edged femme fatale straight out of a Raymond Chandler novel. The episode is fast-paced and frothy and a little bit campy. Perhaps most of all, though, it’s a tour de force of technical film-making: in conscious emulation of Alfred Hitchcock’s experimental classic Rope, its 45 minutes consist of just 24 ultra-extended single-camera takes. (By way of comparison, the average X-Files episode contained around 1000 switches of perspective.) “To watch ‘Triangle’ now,” writes the critic Emily St. James, “is to remember a time when this was the most daring show on television.”

The two-parter “Dreamland,” written by Vince Gilligan, John Shiban, and Frank Spotnitz, opens with Mulder and Scully on yet another nighttime drive to Area 51 to meet yet another shadowy contact who may or may not be who he says he is. In what can all too easily be read as a meta-fictional message to a certain kind of rabid X-Files fan, Scully idly wonders whether the two of them will ever outgrow this stuff and make better, fuller lives for themselves. Shortly thereafter, they get waylaid by the authorities, the infamous Men In Black who are always lurking around places like this. But then a test of an alien spacecraft creates a quantum disturbance that swaps Mulder’s consciousness into the lead MiB’s body, and vice versa. Much discomfort and hilarity ensues, as Mulder learns that being an MiB is just a government job like any other. While he tries to adapt to life as a paunchy, middle-aged family man, his alter ego embraces with gusto the swinging-bachelor lifestyle that Mulder’s looks have always cut him out for. Lessons are learned on both sides, until a way is found to reverse the trend. In other words, this episode turns all of the stuff about aliens and conspiracies into an excuse to tell a more resonant, universal story about life choices, opportunity costs, and roads not taken. Plus it’s really, really funny.

The ghosts in Chris Carter’s “How the Ghosts Stole Christmas” are played by Ed Asner and Lily Tomlin, two stars from an earlier era of television who probably would never have appeared on the show if The X-Files was still shooting in Vancouver. The episode is another meditation on life choices, this one with a spooky Dickensian vibe, with some crackerjack comic-tragic dialog. But my favorite part is the ending, when Mulder and Scully hunker down in the Mulder’s cozy apartment to exchange the gifts they promised one another they wouldn’t buy. It’s hard to imagine an earlier incarnation of the show embracing the spirit of the holidays in such a forthright, non-ironic way.

“Monday,” written by Vince Gilligan and John Shiban, is another episode that concerns time travel — once that genie had been let out of the bottle, it was hard to stuff it back in — along with, yet again, choices and consequences. It’s The X-Files’s version of Groundhog Day. We see the same day play out over and over, a day in which a desperate man with a bomb decides to rob a bank and Mulder and Scully keep getting caught in the crosshairs in different ways.

“Arcadia” by Daniel Arkin is The X-Files meets The Stepford Wives. Mulder and Scully go undercover as a married couple, moving into a white-bread Middle American neighborhood where residents whose lives are insufficiently tidy have a nasty habit of disappearing. The commentary on the horrors of suburban conformity isn’t groundbreaking by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s great fun to watch Mulder and Scully play house for the benefit of the neighbors, passive-aggressively needling one another all the while. It almost goes without saying by this point that the monster at the heart of the case they’re investigating is the least interesting part of the episode.

One of the ways the show’s brain trust tried to keep their stars engaged during the later seasons was to offer them the opportunity to contribute behind the camera as well, by submitting scripts of their own. This sort of gesture doesn’t always turn out well, but David Duchovny at least proved a surprisingly soulful and agile writer, putting his earlier life as a graduate student in literature to good use. In “The Unnatural,” which he directed as well as wrote, he cleverly juxtaposes The X-Files’s standard version of aliens with aliens of another type: the Black baseball players who braved scorn and violence to desegregate the sport in the 1940s. It’s a lovely, luminous episode that oozes the magical-realist quality the show was embracing so successfully by this point. Sure, it owes a lot to Field of Dreams in tone and feel, but it’s hard to disparage it for that. Given the choice between conspiracy theories and the crack of wood on cowhide on a starry summer night, I’ll take the latter every time.

As we saw in an earlier article in reference to the alien-autopsy documentary, The X-Files loved nothing better than to satirize its parent network’s tackier tendencies. One of the urtexts of Fox’s brand of tabloid journalism was the series called Cops, an early example of “reality” television in which a camera crew rode along in the backseat of a police cruiser on the mean streets of a big American city. (Rather astonishingly, Cops is still on television to this day, being in its 36th season as of this writing.) Vince Gilligan’s “X-Cops” is a picture-perfect re-creation of the show, from the Cops theme song and credits sequence that take the place of the standard X-Files version of same to the shaky handheld camerawork, from the suspects and witnesses who live in a liminal space between sympathy and ridicule to the know-it-all police officers who give us the benefit of their hard-won wisdom in running commentaries. Into this hard-bitten milieu are dropped Mulder and Scully on the trail of a monster of the week. It’s incongruous and bizarre and most of all hilarious, another of those episodes that are so brave and cheeky and completely out of the box that it’s hard to believe they were actually made. Who would ever have imagined during the first season of The X-Files that the premise would someday be bent far enough to yield episodes like this one?

Lately I’ve been indulging in a thought experiment, or maybe more of a wish-fulfillment fantasy. Wouldn’t it have been neat if The X-Files had taken a bow already after a sixth season that was absolutely spectacular? Said season would have been created by junking all of the increasingly tiring and tiresome mythology episodes from the extant sixth and seventh seasons and then throwing out the handful of clunkers among the standalone episodes as well. Do all that, and you’d end up with what I’m going to have the audacity to call one of the best single seasons of television ever created. Such a victory tour would necessarily conclude with Vince Gillian’s “Je Souhaite,” the last standalone episode of the real seventh season, an episode that’s as universal as a fairy tale — which is almost literally what it is, come to think of it. Here Mulder and Scully meet a genie — yes, complete with the bottle — who has the power to grant three wishes. We all know how stories like this tend to go. Be very, very careful what you wish for, kids! When Mulder gets his chance to wish, he asks for peace on Earth — not a good choice, because the easiest way to achieve that is to simply remove the species that has been causing all of the chaos on our planet all these centuries. But then, after using his second wish to undo his first and repopulate the planet, he hits upon the perfect third wish, by looking at the genie herself with eyes of empathy. The best way to change the world, he realizes, is by showing kindness to the people who are right there in front of you. What a perfect grace note that would have been for the show to go out on…

Whether you love or hate the sun-kissed X-Files of the sixth season and beyond, there can be no question that it marked a commercial turning point for the show — and not in a good way. By the end of the sixth season, the average episode’s viewership had dropped by almost 25 percent from what it had been just one year earlier. Measured by the standard metrics, The X-Files was still a popular show, but it no longer took pride of place at the center of the zeitgeist, no longer garnered shiny awards and glossy magazine covers and navel-gazing think-pieces from critics and pundits. It had reached the top of its mountain of destiny a year earlier, and now it was on the downward slope that lay just beyond.

What were the reasons for its decline? I’m tempted to say it had something to do with the mythology episodes that had always dominated in public discussion of the show. These had by now grown so convoluted and ridiculous that it was becoming hard for even the most sanguine optimist to believe they were going anywhere coherent. (Scully is abducted by aliens! Scully is back! Scully has incurable alien-caused brain cancer! Scully is cured! The aliens aren’t real, they were just a carefully engineered distraction all along! No, belay that, actually the aliens are real! Mulder is abducted! Mulder is back!) “The mythology was becoming an awful lot for people to continue to keep track of,” admits X-Files executive producer and writer Frank Spotnitz.

At the same time, though, this objection hardly began with the sixth season. The more encompassing explanation for the show’s decline in popularity is likely the simple fact that even the biggest cultural phenomena always run their course and then give way to fresh things. To wit: right in the middle of The X-Files’s sixth season, the cable-television channel HBO aired the first episode of The Sopranos, a heavily serialized mobster drama that was free of most of the strictures of broadcast television, among them restrictions on language, violence, and sexual content, a rigid 45-minute running time for every single episode, and the need to churn out twenty episodes or more every single season. The Sopranos inaugurated the fifteen-year stretch that some critics today like to call The Golden Age of Cable Television, during which the medium eclipsed theatrical films in many respects to become the most prestigious and satisfying of all forms of moving image. In illustrating that long-term serialized storytelling could attract a mass audience on television in genres other than the soap opera, The X-Files was an important forerunner to shows like The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad. But it was not one of their peers.

The gradual decline of The X-Files’s popularity continued in the seventh season. Chris Carter and his colleagues actually went into the season thinking it would probably be the last. Not only were the ratings getting slowly but inexorably worse, but the contracts of David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson were due to run out once again when the season was over, and Duchovny was less interested than ever in renewing his. In fact, he was suing Fox and Chris Carter personally for allegedly selling syndication rights to the show to a subsidiary network for less than their full market value, which impacted his own residual earnings. As one would expect, the legal battle “didn’t help the creative energy,” as Carter put it.

This late in its run, the show had just one surefire way of making headlines again, however briefly. In light of this, the makers’ handling of the transition of Mulder and Scully from platonic partners to a romantic couple is as bizarre as any monster of the week that ever appeared on the show. In Vince Gilligan and Frank Spotnitz’s “Millennium” — an episode whose main function was providing closure for the semi-spinoff series of the same name, which had been abruptly cancelled after three seasons — Mulder and Scully celebrate the arrival of Y2K by sharing their first ever onscreen kiss. Thirteen episodes later, in “All Things,” which was written and directed by Gillian Anderson, it’s off-handedly revealed that the two are now sleeping in the same bed. And that’s it. Restraint has its virtues, but come on! Shippers who had been waiting 150 episodes for the other shoe — or perhaps some other articles of clothing — to drop were rewarded with this damp squib. I have no idea why the makers didn’t turn “Mulder and Scully finally do the deed!” into a mass-media event. As it was, they squandered their last bit of dry powder from their glory days in about as anticlimactic a fashion as can be imagined.

The show easily could have — and probably should have — ended after the seventh season. Yet it didn’t. David Duchovny agreed to settle his lawsuit with Fox, and then shocked everyone by agreeing as well to play Mulder just a little bit longer — for another half of a season, to be precise. The powers that were at Fox decided that was good enough for them, especially given that they didn’t have any strong candidates to hand to air in place of The X-Files on Sunday nights. And so it was on to the eighth season. It was decided that Mulder would be absent for the first half of the season, having been abducted by aliens. (What other explanation could there possibly be?) Then he would return for the second half, so that the show could finish strong.

An actor named Robert Patrick won the unenviable role of Special Agent John Doggett, the replacement for one of the most iconic television characters of recent history. This may explain why everyone was at such pains not to call him a replacement. “Robert Patrick is an addition to the show,” insisted Chris Carter. When David Duchovny did come back halfway through the season, he immediately began to complain loudly about having become “peripheral. Mulder’s story was one of three stories going on and it didn’t feel like the same show to me.” At the risk of editorializing too much, I must say that my mind is fairly boggled by the egotism on display in this comment. What did he expect would happen?

By the last episode of the eighth season, when Mulder and Scully had a baby together, the proverbial shark had been pretty well jumped. And yet the second half of the season, after Duchovny’s return, actually managed to slightly outdraw the end of the previous one with the viewing public. The show got renewed yet again, even though Duchovny now declared himself to be gone for good — no ifs, ands, or buts about it.

The first episode of the ninth season had yet to air when, on September 11, 2001, terrorists hijacked four American passenger planes, flying two of them into the World Trade Center in New York City and one into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. (The hijackers of the fourth airplane, which was intended for the White House, met with heroic resistance from the passengers, and that plane wound up crashing over Pennsylvania, killing everyone onboard.) The X-Files was something of a shambling anachronism already by that point in the eyes of most television viewers, but this tragic day of infamy cemented that status. The mood of the nation changed on a dime; just like that, the epoch that some now call “The Long Nineties” came to a smashing end.

The 1990s had been the Age of Irony, when an anthemic hit single could be named after a brand of teenybopper deodorant, when videogames like Duke Nukem 3D were reveling gleefully in senseless violence amidst the trashy detritus of conspicuous consumption. And why should it have been otherwise, during a decade whose biggest ongoing news story was the dot.com bubble? “We’re the middle children of history, man,” said Brad Pitt of Generation Slacker in Fight Club. “We have no Great War, no Great Depression.”

Earnestness made a big comeback after September 11. Suddenly people had a cause again, Wanted to Believe again — not in the existence of aliens, conspiracy theories about which now seemed like the childish diversions that they had always been, but in the very government and military the conspiracy theorists had spent so many years questioning if not reviling. By September 21, the approval rating of President George W. Bush, who had lost a national popular vote to Al Gore just ten months earlier but squeaked out a controversial win in the Electoral College, had soared to 90 percent, the highest ever recorded.

It was difficult to imagine how any show could be more out of step with the changed times than The X-Files was. “The X-Files is the product of a time that is passed,” wrote the columnist Andrew Stuttaford. “It is a relic of the Clinton years, as dated as a dot.com share certificate, a stained blue dress, or Kato Kaelin’s reminiscences.” All of which is to say that it was all but foreordained that its ninth season would be its last before said season ever aired its first episode. The new standard bearer of the American zeitgeist was 24, another serialized show about a law-enforcement agent, but this time one who had no doubts whatsoever about the righteousness of his country or his government, a two-fisted true believer who wasn’t above a spot of torture when it was the only way to foil the Axis of Evil. Pop music and videogames too heeded the call: Celine Dion’s nerve-jangling rendition of “God Bless America” climbed the charts as the lead single of a charity album of the same name, while Duke Nukem yielded to Call of Duty.

Amidst it all, The X-Files shambled through its last season as best it could. (Raising a defiant middle finger to the scoffers, the makers even named one episode “Jump the Shark.”) David Duchovny, whose career as a cinematic leading man wasn’t going quite so well as he had thought it would, agreed to rejoin the cast for a 90-minute series finale, which endeavored to wrap up the mythology story lines about as neatly as could be done in that span of time. “It gives viewers answer after answer, until it feels like we’re reading somebody’s Geocities fan page for wild theories about the show,” writes Emily St. James of the finale. “But it’s also dramatically, death-defyingly boring.” When all was said and done, Cancer Man got blown up by a helicopter and everyone else rode off into the sunset of a changed America.

But they didn’t go away forever. Anyone at all familiar with the post-millennial media landscape knows that nothing ever seems to go away forever. There have been two attempts to date to revive The X-Files since that last hurrah of 2002.

In 2008, Chris Carter got the old gang back together for a movie. The X-Files: I Want to Believe had a budget less than half the size of the first X-Files film before adjusting for inflation. “It’s funny, but on the series we prided ourselves each week with making a little movie,” muses Carter. “Then, when it came time to do the second X-Files movie, we were given the money and the opportunity to make, literally, a little movie.” Probably smartly, he chose to do an expanded monster-of-the-week episode rather than reopening the Pandora’s box of the mythology. Even so, it was hard to figure out what reason the film really had to exist; it came a little too soon to be a full-blown nostalgia play, even as its moody atmosphere still felt badly out of joint with the times around it during that summer of 2008, when Barack Obama’s “Yes, We Can!” was the slogan of the moment. The critics were not impressed, and its box-office receipts were less than a third of the first film’s — again, without adjusting for inflation.

Seven and a half years later, Carter made a more concerted effort to revive the show, this time as another television series on Fox — albeit one with dramatically truncated episode counts in comparison to those of its original run. By now, the times were falling more into step with The X-Files’s tendency to see everything in the world through the lens of conspiracy. (More on that subject momentarily.) Nevertheless, the new episodes never quite landed like a lot of observers expected them to. The scripts felt underwhelming, the alien stuff way past its sell-by date, and one at least of the two leads seemed a little bored and distracted. Ironically, it was Gillian Anderson now who wasn’t at all sure she wanted to be there, and who most obviously turned in performances that reflected this ambivalence. The fact was that she was a more sought-after actor than David Duchovny this far along in their respective careers, with a larger number of interesting roles in both her past and her future.

Darin Morgan, the man who first made The X-Files safe for comedy, came back to pen “Mulder and Scully Meet the Were-Monster,” one of the few episodes where the revival found some creative traction. The lizard-man in tighty whities who serves as the monster of the week here turns out to be a normal lizard who got bit by a human. After spending some time on a job peddling mobile-phone plans in an anonymous strip mall, all he wants to do is become a lizard once again. And who can blame him?

The revival sputtered out in 2018, after two seasons with a total of sixteen episodes between them. As of this writing, The X-Files’s legacy is once more being left in peace. But never say never, especially in these current times of ours when nostalgia is a bigger business than it has ever been.

And what can we say about the legacy of The X-Files now, a quarter-century after its high time in the zeitgeist?

Well, as I think that even many of its most zealous boosters will admit by now, it was a show subject to wild swings in quality, not just from season to season but from week to week. When all is said and done, The X-Files probably produced only about 20 to 25 episodes — that is to say, about one season’s worth of them, in the course of nine seasons — that might legitimately be called classics. Still, that’s a lot more than nothing, and a better batting average than the vast majority of television shows achieve. And betwixt and between its standout moments of brilliance, The X-Files offered plenty more episodes that remain perfectly watchable today despite their flaws, especially if you’re one of those who can enjoy just hanging out with its two charming leads.

On the broader canvas of television history, The X-Files occupies an important position. It wasn’t the first show to have survived thanks largely to the activism of a relatively small group of passionate fans — the original Star Trek leaps immediately to mind as a much earlier instance of same — but it was the first to be joined at the hip from the get-go with Internet fandom. In this sense, it was a harbinger of a new reality, in which almost every artifact of traditional media would have to adjust to a life spent in a symbiotic relationship with cyberspace.

Then, too, as I already noted, the mythology episodes paved the way for the Golden Age of Cable Television by serving as a demonstration of both the power of long-form storytelling on television and, less happily but no less usefully, of some of the ways it can go wrong. The conspiracy angle in The X-Files quickly became, to steal a phrase from the Cold War historian David Martin, a “wilderness of mirrors.” Partly this was down to aesthetic intent, but it was equally down to practical necessity. The only way to keep the conspiracy story arc going was to just keep putting more and more mirrors in the heroes’ way. Later serialized shows — not all of them by any means, but a lot of them — would use more limited seasonal episode counts, or in some cases entire runs that were planned as limited from the start, to do better on this front. We should never forget that, in this respect as in a number of others, The X-Files was a pioneer, with few if any examples to follow; we therefore shouldn’t be overly surprised that it did so much wrong. Indeed, the media world into which it was born made it effectively impossible for it to do some of what shows like The Sopranos and Breaking Bad later did so well. In short, The X-Files’s creators played the cards they were dealt as well as they knew how, and there’s never any shame in that.

All that said, there does remain another sense in which The X-Files seems today less like a brave pioneer and more like one of the shadowy agents of evil who featured so prominently in so many of its episodes, and it’s this elephant in the room with which I feel sadly obliged to close this series of articles.

Chris Carter most definitely didn’t invent conspiracy theories; the roots of the modern fixation on evil cabals manipulating events behind the scenes can be traced back at least as far as 1903 and the infamous antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Yet conspiracy theories have been weaponized in the years since The X-Files went off the air to a degree arguably not seen since the Nazis used them as a partial justification for the Holocaust. Carter himself was never a committed believer in UFO conspiracies; he saw them first and foremost as a cool set of ready-made fictions around which to build his show. Many or most fans of said show doubtless saw them the same way. But, by doing so much to break conspiracy culture into the American mainstream, The X-Files must shoulder some small portion of the blame for what seems to be an increasingly post-truth United States, where uncomfortable facts like electoral defeats can be hand-waved away with claims of voter fraud, where essential public-health measures like vaccines can be imagined to be agents of mind control, where people can convince themselves to kill in the cause of thwarting an international pedophile ring being run out of a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor, and where duly elected members of Congress can tell us that the current administration in the White House is attacking the parts of the country that it doesn’t like with bespoke hurricanes. This is the poison pill lurking behind that iconic poster hanging on Mulder’s wall. If everyone decides that just “wanting” to believe is justification enough for doing so, this world of ours is going to wind up in a very bad place. It strikes me as deeply unfortunate that, in all of its 218 episodes and two movies, The X-Files never saw fit to address the deeper psychological dilemma of such a smart man who would tack such a dumb poster to his wall. On the contrary, as late as the first revival season in 2016, the show was presenting in a fairly heroic light a conspiracy monger who is quite plainly based on Alex Jones of InfoWars, a pernicious huckster of dangerous, reactionary nonsense. In a recent survey of X-Files fan attitudes conducted by the academic researcher Bethan Jones, one anonymous respondent said that “I always thought of The X-Files in retrospective as an (incidental?) instrument [in] getting people to become paranoid of their government, which is an instrument of the real power to manipulate democracies.” This seems to me a fair assessment.

Of course, The X-Files is at the very worst a small proximate cause of the situation in which we find ourselves today. And yet even its tiny portion of the blame is enough to cast a faint shadow over any retrospective like this one. It took us a long time to go from the alien-autopsy film to QAnon, but it seems safe to say that The X-Files had a hand in propagating both of them. The best we can do now is hope the day will come when it can be remembered as just a groundbreaking television show again, with no further prevarication required. Until then, it will have to remain both a victim and a proof of a force that is more insidiously frightening than any alien invasion: the law of unintended consequences.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books “Deny All Knowledge”: Reading the X-Files, edited by David Lavery, Angela Hague, and Marla Cartwright; Conspiracy Culture: From Kennedy to The X-Files by Peter Knight; Monsters of the Week: The Complete Critical Companion to The X-Files by Zack Handlen & Emily St. James; X-Files Confidential: The Unauthorized X-Philes Compendium by Ed Edwards; Cue the Sun!: The Invention of Reality TV by Emily Nussbaum; The Legacy of The X-Files, edited by James Fenwick and Diane A. Rogers; Opening the X-Files: A Critical History of the Original Series by Darren Mooney; and The Nineties: A Book by Chuck Klosterman. Computer Gaming World of August 1998.

Online sources include “X-Files Creator Wants You to Chill Out on the Conspiracy Theories” by Jordan Hoffman at Vanity Fair.