Fair warning: this article includes plot spoilers of Final Fantasy VII.

Historians and critics like me usually have to play the know-it-all in order to be effective at our jobs. My work flow begins with me going out and learning everything I can about a topic in the time I have available. Then I decide what I think about it all, find a way to structure my article, and share it with you as if I’ve been carrying all this information around with me all my life. Often I get things wrong, occasionally horribly wrong. But I can always count on you astonishingly knowledgeable folks to set me straight in the end, and in the meantime being direct is preferable in my book to equivocating all over the place. For, with the arguable exception of a wide-eyed undergraduate here or there enrolled in her first class in postmodern studies, absolutely no one wants to read a writer prattling on about the impossibility of achieving Complete Truth or the Inherent Subjectivity of criticism. Of course complete truth is an unattainable ideal and all criticism is subjective! I assume that you all know these things already, so that we can jump past the hand-wringing qualifiers and get right to the good stuff.

Still, I don’t believe that all criticism is of equal value, for all that it may in the end all be “just, like, your opinion man!” The most worthwhile criticism comes from a place of sympathy with the goals and expectations that surround a work and is grounded in an understanding of the culture that produced it. It behooves no one to review a blockbuster action movie as if it was an artsy character study, any more than it makes sense to hold, say, Michael Crichton up to the standards of fine literature. Everything has its place in the media ecosystem, and it’s the critic’s duty to either understand that place or to get out of the way for those that do.

Which goes a long way toward explaining why I start getting nervous when I think about rendering a verdict on Final Fantasy VII. I am, at best, a casual tourist in the milieu that spawned it; I didn’t grow up with Japanese RPGs, didn’t even grow up with videogame consoles after I traded my Atari VCS in for a Commodore 64 at age eleven. Sitting with a game controller in my hand rather than a keyboard and mouse or joystick is still a fairly unfamiliar experience for me, almost 40 years after it became the norm for Generation Nintendo. My experience with non-gaming Japanese culture as well is embarrassingly thin. I’ve never been to Japan, although I did once glimpse it from the Russian island of Sakhalin. Otherwise, my encounters with it are limited to the Star Blazers episodes I used to watch as a grade-school kid on Saturday mornings, the World War II history books I read as an adolescent war monger, that one time in my twenties when I was convinced to watch Ghost in the Shell (I’m afraid it didn’t have much impact on me), a more recent sneaking appreciation for the uniquely unhinged quality of some Japanese music (which can make a walking-blues vamp sound like the apocalypse), and the Haruki Murakami novels sitting on the bookshelf behind me as I write these words, the same ones that I really, really need to get around to reading. In summation, I’m a complete ignoramus when it comes to console-based videogames and Japan alike.

So, the know-it-all approach is right out for this article; even I’m not daring enough to try to fake it until I make it in this situation. I hesitate to even go so far as to call what follows a review of Final Fantasy VII, given my manifest lack of qualifications to write a good one. Call it a set of impressions instead, an “old man yells at cloud” for the JRPG world where the joke is quite probably on the old man.

In a weird sort of way, though, maybe that approach will work out okay, just this once. For, as we learned in the last article, Final Fantasy VII was the first heavily hyped JRPG to be released on computers as well as consoles in the West. When that happened, many computer gamers who were almost as ignorant then as I am now played it. As I share my own experiences below, I can be their voice in this collision between two radically different cultures of gaming. The fallout from these early meetings would make games as a whole better in the long run, regardless of the hardware on which they ran or the country where they were made. It’s this gratifying ultimate outcome that prompted me to write this trilogy of articles in the first place. Perhaps it even makes my personal impressions relevant in this last entry of said trilogy, despite my blundering cluelessness.

Nevertheless, given the intense feelings that JRPGs in general and this JRPG in particular arouse in their most devoted fans, I’m sure some small portion of you will hate me for writing what follows. I ask only that you read to the end before you pounce, and remember that’s it’s just my opinion, man, and a critic’s aesthetic judgments do not reflect his moral character.

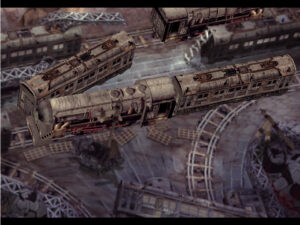

The trains in Final Fantasy VII look like steam locomotives. This doesn’t make much sense, given what we know of the technology in use in the city of Midgar, but it’s kind of cool.

I had heard a lot about Final Fantasy VII before I played it, most of it extremely positive, to put it lightly. In fact, I had seen it nominated again and again for the title of Best Game Ever. For all that I have no personal history with JRPGs, I do like to think of myself as a reasonably open-minded guy. I went into Final Fantasy VII wanting to be wowed, wanting to be introduced to an exciting new world of interactive narrative that stood apart from both the set-piece puzzle-solving of Western adventure games and the wide-open emergent diffusion of Western RPGs. But unfortunately, my first couple of hours with Final Fantasy VII were more baffling than bracing. I felt a bit like the caveman at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey, trying to figure out what I was supposed to be doing with this new bone I had just picked up.

After watching a promisingly understated opening-credits sequence, accompanied by some rather lovely music, I started the game proper. I was greeted with a surreal introductory movie, in which a starry sky morphed into scenes from a gritty, neon-soaked metropolis of trains and heavy industry, with an enigmatic young girl selling flowers amidst it all. Then several people were leaping off the top of a train, and I realized that I was now controlling one of them. “C’mon, newcomer!” shouted one of the others. “Follow me.” I did my best to oblige him, fumbling through my first combat — against some soldierly types who were chasing us for some reason — along the way.

The opening credits are the last part of Final Fantasy VII that can be described as understated. From that point on, even the swords are outsized.

Who the hell was I? What was I supposed to be doing? Naïve child of 1980s computer gaming that I was, I thought maybe all of this was explained in the manual. But when I looked there, all I found were some terse, unhelpful descriptions of the main characters, not a word about the plot or the world I had just been dropped into. I was confused by everything I saw: by the pea soup of bad translation that made the strictly literal meanings of the sentences the other characters said to me impossible for me to divine at times; by the graphics that sometimes made it hard to separate depth from height, much less figure out where the climbable ladders and exit points on the borders of the maps lay; by the way my character lazily sauntered along — “Let’s mosey!”, to quote one of the game’s famously weird translations — while everyone else dashed about with appropriate urgency; by the enemies who kept jumping me every minute or two while I beat my head against the sides of the maps looking for the exits, enemies whom I could dispatch by simply mashing “attack” over and over again; by the fact that I seemed to be a member of a terrorist cell set on blowing up essential civic infrastructure, presumably killing an awful lot of innocent people in the process; by the way the leader of my terrorist group, a black man named Barret, spoke and acted like Mr. T on old A-Team reruns, without a hint of apparent irony.

What can I say? I bounced. Hard. After I made it to the first boss enemy and died several times because, as I would later learn from the Internet, the shoddy English translation was telling me to do the exact opposite of what I needed to do to be successful against it, I threw the game against the metaphorical wall. What did anyone see in this hot mess, I asked my wife — albeit in considerably more colorful language than that. She just laughed — something that, to be fair, she spends a lot of time doing when I play these crazy old games on the television.

The first hill on which I died. Final Fantasy VII‘s original English translation is not just awful to read but actively wrong in places. When you meet the first boss monster, you’re told to “attack while it’s [sic] tail’s up!” The Japanese version tells you not to attack when its tail’s up. Guess which one is right…

I sulked for several weeks, deeply disappointed that this game that I had wanted to be awesome had turned out to be… less than awesome. But the fact remained that it was an important work, in the history of my usual beat of computer gaming almost as much as that of console gaming. Duty demanded that I go back in at some point.

When that point came, I steeled myself to fight harder for my pleasure. After all, there had to be some reason people loved this game so, right? I read a bit of background on the Internet, enough to understand that it takes place on an unnamed world whose economy is dominated by an all-powerful mega-corporation called the Shinra Electric Power Company, which provides energy and earns enormous profits by siphoning off the planet’s Mako, a sort of spiritual essence. I learned that AVALANCHE, the terrorist cell I was a part of, was trying to break Shinra’s stranglehold, because its activities were, as Barret repeats ad nauseum, “Killin’ the planet.” And I learned that the main character — the closest thing to “me” in the game — was a cynical mercenary named Cloud Strife, a former member of a group called SOLDIER that did Shinra’s dirty work. But Cloud has now switched sides, joining AVALANCHE strictly for the paycheck, as he makes abundantly clear to anyone who asks him about it and most of those who don’t. The action kicks off in the planet’s biggest city of Midgar, with AVALANCHE attempting to blow up the Shinra reactors there one by one.

With that modicum of background information, everything began to make a little more sense to me. I also picked up some vital practical tips on the Internet. For example, I discovered that I could push a button on the controller to clearly mark all ladders and exits from a map, and that I could hold down another button to make Cloud run like everybody else; having to do so basically all the time was a trifle annoying, but better than the alternative of moseying everywhere. I learned as well that I could turn off the incessant random encounters using a fan-made application called 7th Heaven, but I resisted the temptation to do so; I was still trying to be strong at this point, still trying to experience the game as a player would have in the late 1990s.

Things went better for a while. By doing the opposite of what the bad translation was telling me to do, I got past the first boss monster that had been killing me. (Although I didn’t know it at the time, this would prove to be the the only fight that ever really challenged me until I got to the very end of the game). Then I returned with the others to our terrorist hideout, and agreed to help AVALANCHE blow up the next reactor. (All in a day’s work for a mercenary, I suppose.) While the actual writing remained more or less excruciating most of the time, I started to recognize that there was some real sophistication to the narrative’s construction, that my frustration at the in medias res beginning had been more down to my impatience than any shortcoming on the game’s part. I realized I had to trust the game, to let it reveal its story in its way. Likewise, I had to recognize that its environmentalist theme, a trifle heavy-handed though it was, rang downright prescient in light of the sorry state of our own planet a quarter-century after Final Fantasy VII was made.

Which isn’t to say that it was all smooth sailing. After blowing up the second Mako reactor, Cloud was left dangling from a stray girder, hundreds of feet above the vaguely Blade Runner-like city of Midgar. After some speechifying, he tumbled to his presumed doom — only to wake up inside a cathedral, staring into the eyes of the flower girl from the opening movie. “The roof and the flower bed must have broken your fall,” she said. While my wife was all but rolling on the floor laughing at the sheer ridiculousness of this idea, I bravely SOLDIERed onward, learning that the little girl’s name was Aerith and that she was being stalked by Shinra thugs due to some special powers they believed her to possess. “Take me home,” she begged Cloud.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” he grunted in reply. “But it’ll cost you.” (Stay classy, Cloud… stay classy.)

And now I got another shock. “Well, then, let’s see…” Aerith said. “How about if I go out with you once?” Just like that, all of my paradigms had to shift. Little Aerith, it seemed, wasn’t so little after all. Nonetheless, playing Cloud in this situation left me feeling vaguely unclean, like a creepy old guy crashing his tweenage daughter’s slumber party.

Judging from his facepalm, Cloud may have been as shocked by Aerith’s offer of affection for protection as I was.

Ignoramus though I was, I did know that Japanese society is not generally celebrated for its progressive gender politics. (I do think this is the biggest reason that anime and manga have never held much attraction for me: the tendency of the tiny sliver of it which I’ve encountered to simultaneously infantalize and sexualize girls and women turns me right off.) Now, I realized that I — or rather Cloud — was being thrown into a dreaded love triangle, its third point being Cloud’s childhood friend and fellow eco-terrorist Tifa. Going forward, Aerith and Tifa would spend their character beats snipping at one another when not making moon-eyes at Cloud. Must be something about that giant sword he carries around, tucked only God knows where inside his clothing…

I was able to identify Tifa as an adult — or at least an adolescent — from the start, thanks to her giant breasts, which she seems to be trying to thrust right out of the screen at you when you win a fight, using them as her equivalent of Cloud’s victoriously twirling sword. (This was another thing my wife found absolutely hilarious…) The personalities of the women in this game demonstrate as well as anything its complete bifurcation between gameplay and story. When you control Aerith or Tifa in combat, they’re as capable as any of the men, but when they’re playing their roles in the story, they suddenly become fragile flowers utterly dependent on the kindness of Cloud.

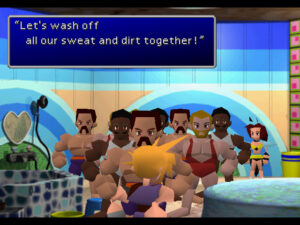

Anyway, soon we got to Wall Market. Oh, my. This area is unusual in that it plays more like a puzzle-based adventure game than anything else, featuring no combat at all — what a blessed relief that was! — until the climax. Less positively, the specific adventure game it plays like is Leisure Suit Larry at its most retrograde. Tifa gets abducted and forced to join the harem of a Mafia kingpin-type named Don Corneo, and it’s up to Cloud and Aerith to rescue her. Aerith decides that the only way to get Cloud inside Corneo’s mansion and effect the rescue is to dress him up like… gasp… a girl! This suggestion Cloud greets with appropriate horror, understanding as he does that the merest contact with an article of female clothing not hanging on a female body carries with it the risk of an instant and incurable case of Homosexuality. But he finally comes around with all the good grace of a primary cast member of Bosom Buddies. Many shenanigans ensue, involving a whorehouse, a gay bathhouse, erectile dysfunction, a “love hotel,” cross-dressing bodybuilders, and a pair of panties, all loudly Othered for the benefit of the insecure straight male gaze. What the hell, I wondered for the umpteenth time, had I gotten myself into here?

But I didn’t let any of it stop me; I pushed right on through like the SOLDIER Cloud was. No, readers, what broke me wasn’t Don Corneo chasing Cloud-in-a-dress around his bedroom, but rather the goddamn train graveyard. Let me repeat that with emphasis… the goddamn train graveyard.

In a way, this area illustrates one of Final Fantasy VII‘s more admirable attributes, its determination to give you a variety of different stuff to do. It’s a combination of a maze and a sort of Sokoban puzzle, as you must climb in and over broken-down train carriages and engines in an abandoned depot, even sometimes putting on your engineer’s cap and driving a locomotive out of the way. This is fine in and of itself. What I found less fine was, as usual, the random combat. I would be working out my route in my pokey middle-aged way, coming up with a plan… and then the screen would go all whooshy and the battle music would start, and I’d have to spend the next 30 seconds mashing the attack button before I could get back to the navigational puzzle, by which time I’d completely lost track of what I had intended to do there. Rinse and repeat. Words cannot express how much I had learned to loath that battle music already, but this took the torture to a whole new level, as combat seemed to come at twice, thrice, five times the rate of before. I just couldn’t take it anymore. I quit. Not willfully… I just stopped playing one evening and didn’t start again the next. Or the next. Or the one after that. You know how it goes.

So, real life went on. But as it did so, my conscience kept pricking me. This game is important, it said. People love this game. Can you not find some way to make friends with it?

I decided to give it one last shot. This time, however, I would approach it differently. Final Fantasy VII has a passionate, active fan community — have I told you that people love this game? — who have done some rather extraordinary things with it over the years. I already mentioned one of these things in passing: 7th Heaven, an application that makes it effortless to install dozens of different “mod” packages, which can alter the game in ways both trivial and major, allowing you to play Final Fantasy VII exactly the way that you wish.

Now, I normally consider such things off-limits; my aim on this site is to give you the historical perspective, which means playing and reviewing games as their original audience would have known them. Still, I decided that, if it could help me to see the qualities other people saw in Final Fantasy VII that I all too plainly was not currently seeing, it might be okay, just this one time. I installed 7th Heaven and started to tweak away. First and foremost, I turned off the random encounters. Then I set it up so Cloud would run rather than mosey by default. Carried away by my newfound spirit of why the heck not, I even replaced the Windows version’s tinny MIDI soundtrack with the PlayStation version’s lusher music.

And then, having come this far, I really took the plunge. A group of fans who call themselves “Tsunamods” have re-translated all of the text in the game from the original Japanese script. As if that wasn’t enough, they’ve also found a way to add voice acting, covering every single line of dialog in the game. I went for it.

I was amazed at the difference it made — so amazed that I felt motivated to start the game all over from the beginning. The Tsunamods voice acting is way, way better than it has any right to be — far better than the average professional CD-ROM production of the 1990s. Being able to listen to the dialog flowing by naturally instead of tapping through text box after text box was a wonderful improvement in itself. But I was even more stunned by the transformation wrought by the fresh translation. Suddenly the writing was genuinely good in places, and never less than serviceable, displaying all sorts of heretofore unsuspected layers of nuance and irony. Instead of fawning all over Cloud like every teenage boy’s sexual fantasy, Aerith and Tifa took a more bantering, patronizing attitude. The Wall Market sequence especially displayed a new personality, with Aerith now joshing and gently mocking Cloud for his hetero horror at the prospect of donning a dress. Even Barret evinced signs of an inner life, became something more than an inadvertent caricature of Mr. T. when he expressed his love for the little orphan girl to whom he’d become surrogate father. And I could enjoy all of this without having to fight a pointless random battle every three minutes; only the meaningful, plot-dictated fights remained. I was, to coin a phrase, in seventh heaven. I had abandoned all of my principles about fidelity to history, and it felt good.

At the same time, though, I wasn’t really sure whose game I was playing anymore. In his YouTube deconstruction of Final Fantasy VII‘s original English translation, Tim Rogers states that “I believe that no such thing exists as a ‘perfect’ translation of a work of literature from one language to another. All translation requires compromise.” I agree wholeheartedly.

For the act of translation — any act of translation — is a creative act in itself. Even those translations which strive to be as literal as possible — which in my opinion are often the least satisfying of them all — are the product of a multitude of aesthetic choices and of the translator’s own understanding of the source text. In short, a work in translation is always a different work from its source material. This is why Shakespeare buffs like me get so upset when people talk about “modernizing” the plays and poetry by translating them into 21st-century English. If you change the words, you change the works. Whether you think it’s better or worse, what you end up with is no longer Shakespeare. The same is true of the Bible; the King James Bible in English is a different literary work from the Hebrew Old Testament or the Greek New Testament. (This is what makes the very idea of Biblical Fundamentalism — of the Bible as the incontrovertible Word of God — so silly on its face…)

Needless to say, all of this holds equally true for Final Fantasy VII. When that game was first translated into English, it became a different work from the Japanese original. And when it was translated again by Tsunamods, it became yet another work, one reflecting not only these latest translators’ own personal understandings and aesthetics but also the changed cultural values of its time, more than twenty years after the first translation was done.

Of course, we can attempt to simply enjoy the latest translation for what it is, as I was intermittently able to do when I could shut my historian’s conscience off. Yet that same conscience taunts me even now with questions that I may never be able to answer, given that I don’t expect to find the time and energy in my remaining decades to become fluent in Japanese. Lacking that fluency, all I am left with are suppositions. I strongly suspect that the first English translation of Final Fantasy VII yielded a work that was cruder and more simplistic than its Japanese source material. Yet I also suspect that the latest English translation has softened many of the same source material’s rough edges, sanding away some racism, misogyny, and homophobia to suit the expectations of a 21st-century culture that has thankfully made a modicum of progress in these areas. What I would like to know but don’t is exactly where all of the borders lie in this territory. (Although Tim Rogers’s video essays are worthy in their way, I find them rather frustrating in that they never quite seem to answer the questions I have, whilst spending a lot of time on details of grammar and the like that strike me as fairly trivial in the larger scheme of things.)

What I do know, however, is that the Tsunamods re-translation and voice acting, combined with the other tweaks, finally allowed me to unabashedly enjoy Final Fantasy VII. I was worried in the beginning that forgoing random encounters might leave my characters hopelessly under-leveled, but the combat as a whole is so unchallenging that I found having a bit less experience to actually improve the game, by forcing me to employ at least a modicum of real strategy in some of the boss fights. I had a grand old time with my modified version of the game for the first seven or eight hours especially, when my party was still running around Midgar on the terrorist beat. Being no longer forced to gawk at the writing like a slow-motion train wreck, I could better appreciate the storytelling sophistication on display: the willingness of the plot to zig where conventional genre-narrative logic said it ought to zag, the refusal to shy away from the fact that AVALANCHE was, whatever the inherent justice of its cause, a gang of reckless terrorists who could and eventually did get lots and lots of innocent people killed.

After I carried the fight directly to the Shinra headquarters, I was introduced to the real villain of the story, a fellow named Sephiroth who used to be Cloud’s commanding officer in SOLDIER but had since transcended his humanity entirely through a complicated set of circumstances, and was now attempting to become a literal god at the expense of the planet and everyone else on it. Leaving Midgar and its comparatively parochial concerns behind, Cloud and his companions set off on Sephiroth’s trail, a merry chase across continents and oceans.

This chase after Sephiroth fills the largest chunk of the game by far. Occasionally, dramatic revelations continued to leave me admiring its storytelling ambition. While the tragic death of Aerith at the hands of Sephiroth had perhaps been too thoroughly spoiled for me to have the impact it might otherwise have had, the gradual discovery that Cloud was not at all what he seemed to be — that he was in fact a profoundly unreliable narrator, a novelistic storytelling device seldom attempted in games — was shocking and at times even moving. Whenever the main plot kicked into gear for these or other reasons, I sat up and paid attention.

But a goodly portion of this last 80 percent of the game is spent meandering through lots and lots of disparate settings, from “rocket cities” to beach-side resort towns to a sprawling amusement park of all places, that have only a tangential relation to the real story and that I don’t tend to find as intrinsically interesting as Midgar. I often got restless and a bit bored in these places, with that all too familiar, creeping feeling that my time was being wasted. I’ve played and enjoyed plenty of Western RPGs whose watchword is “Go Forth and Explore,” but that approach didn’t work so well for me here. I found the game’s mechanics too simplistic to stand up on their own without the crutch of a compelling story, while the graphics, much-admired though they were by PlayStation gamers back in the day, were too hazy and samey in that early 3D sort of way to make the different areas stand out from one another in terms of atmosphere. Even the apparent non-linearity of the huge world map proved to be less than it seemed; there is actually only one really viable path through it, although there is a fair amount of optional content and Easter eggs for the truly dedicated to find. Being less dedicated, I soon began to wish for a way to further bastardize my version of the game, by turning off the plot-irrelevant bits in the same way I’d turned off the random encounters. Like a lot of RPGs of the Western stripe as well, Final Fantasy VII strikes me as far, far longer than it needs to be, an enjoyable 25-hour experience blown up to 50 hours or more, even without all those random encounters. I was more than ready for it to be over when I got to the end. The last fight was a doozie, what with my under-leveled characters, but it was nice to be pushed to the limit for once. And then it was all over.

What, then, do I think about Final Fantasy VII when all is said and done? For me, it’s a game that contains multitudes, one that resists blithe summation. Some of it is sublime, some of it is ridiculous. Sometimes it’s riveting, sometimes it’s exhausting. It certainly doesn’t achieve everything it aims for. But then again, how could it? It shoots for the moon, the sun, and the stars all at once when it comes to its story. It wants to move you so very badly that it’s perhaps inevitable that some of it just comes off as overwrought. Still, I’ll take its heartfelt earnestness over bro-dudes chortling about gibs and frags any day of the week, and all day on Sunday. “Can a computer make you cry?” asked another pioneering company almost a decade and a half before Final Fantasy VII was released. Square, it seems, was determined to provide a definitive affirmative answer to that question. And I must admit that the final scene, of ugly old Midgar now overrun with the beautiful fruits of the earth, did indeed leave a drop or two of moisture in the eyes of this nature lover, going a long way toward redeeming some of my earlier complaints. Whatever quibbles I may have with this game, its ultimate message that we humans can and must learn to live in harmony with nature rather than at odds with it is one I agree with, heart, mind, and soul.

My biggest problem with Final Fantasy VII — or rather with the version of it that I played to completion, which, as noted above, is not the same as the one Square created in Japanese — is that it tries to wed this story and message to a game, and said game isn’t always all that compelling. It’s not that there are no good ideas here; I do appreciate that Final Fantasy VII tries to give you a lot of different stuff to do, some of which, such as the action-based mini-games, I haven’t even mentioned here. (Suffice to say now that, while the mini-games won’t blow anyone away, they’re generally good enough for a few minutes’ change of pace.)

Still, and especially if you’re playing without mods, most of the gamey bits of this game involve combat, and the balance there is badly broken. Final Fantasy VII‘s equivalent of magic is a mystical substance called “materia,” which can be imbued with different spell-like capabilities and wielded by your characters. Intriguingly, the materia “levels up” with repeated usage, taking on new dimensions. But the balance of power is so absurdly tilted in favor of the player that you never really need to engage with these mechanics at all; there are credible reports of players making it all the way to the final showdown with Sephiroth without ever once even equipping any materia, just mashing that good old attack button. (To put this in terms that my fellow old-timers will understand: this is like playing all the way through, say, Pool of Radiance without ever casting a spell.) Now, you could say that this is such players’ loss and their failure, and perhaps you’d be partially correct. But the reality is that, if you give them the choice, most players will always take the path of least resistance, then complain about how bored they were afterward. It’s up to a game’s designer to force them to engage on a deeper level, thereby forcing them to have fun.

When I examine the history of this game’s development, I feel pretty convinced why it came to be the way it is. Throwing lots and lots of bodies at a project may allow you to churn out reams of cut scenes and dialog in a record time, but additional manpower cannot do much beyond a certain point to help with the delicate, tedious process of testing and balancing. What with a looming release date precluding more methodical balancing and the strong desire to make the game as accessible as possible so as to break the JRPG sub-genre for good and all in the West, a conscious decision was surely made to err on the side of easiness. In a way, I find it odd to be complaining about this here. I’m not generally a “hardcore” player at all; far more vintage games of the 1980s and 1990s are too hard than too easy for my taste. But this particular game’s balance is so absurdly out of whack that, well, here we are. I do detest mindless busywork, in games as in life, and if mashing that attack button over and over while waiting for a combat to end doesn’t qualify for that designation, I don’t know what does. If it couldn’t be balanced properly, I’d have preferred a version of Final Fantasy VII that played as a visual novel, without the RPG trappings at all. But commercial considerations dictated that that could never happen. So, again, here we are.[1]The game’s tireless fan base has gone to great lengths, here as in so many places, to mitigate its failings by upping the difficulty in various ways. I didn’t investigate much in this area, deciding I had already given the game the benefit of enough retro-fitting with the mods I did employ.

As it was, I found my modified version of Final Fantasy VII intermittently gripping, for all that I never quite fell completely in love with it. It’s inherently condescending for any critic to tell a game’s fans why they love it despite its flaws, and I don’t really want to do that here. That said, it does occur to me that a lot of Final Fantasy VII‘s status in gaming culture is what we might call situational. This game was a phenomenon back in 1997, the perfect game coming at the perfect time, sweeping away all reservations on a tide of novelty and excitement. It was a communal event as much as a videogame, a mind-blower for millions of people. If some of what it was and did wasn’t actually as novel as Generation PlayStation believed it to be — and to be fair, some of it was genuinely groundbreaking by any standard — that didn’t really matter then and doesn’t matter now. Final Fantasy VII brought high-concept videogame storytelling into the mainstream. It didn’t do so perfectly, but it did so well enough to create memories and expectations that would last a lifetime.

Even the romance was perfectly attuned to the times, or rather to the ages of many players when they first met this game. The weirdness of Wall Market aside, Cloud and Aerith and Tifa live in that bracket that goes under the name of “Young Adult” on bookstore shelves: that precious time which we used to call the period of “puppy love” and which most parents still wish lasted much longer, when romance is still a matter of “girls and guys” exchanging Valentines and passing notes in class (or perhaps messages on TikTok these days), when sex — or at least sex with other people — is still more of a theoretical future possibility than a lived reality. (Yes, the PlayStation itself was marketed to a slightly older demographic than this one, but, as I noted in my last article, that made it hugely successful with the younger set as well, who always want to be doing what their immediate elders are.) I suspect that I too would have liked this game a lot more if I’d come to it when the girls around me at my school and workplace were still exotic, semi-unknowable creatures, and my teenage heart beat with tender feelings and earthier passions that I’d hardly begun to understand.

In short, the nostalgia factor is unusually strong with this one. Small wonder that so many of its original players continue to cherish it so. If that causes them to overvalue its literary worth a bit, sometimes claiming a gravitas for it not entirely in keeping with what is essentially a work of young-adult fiction… well, such is human nature when it comes to the things we cherish. For its biggest fans, Final Fantasy VII has transcended the bits and bytes on the CDs that Square shipped back in 1997. It doesn’t exist as a single creative artifact so much as an abstract ideal, or perhaps an idealized abstraction. Like the Bible, it has become a palimpsest of memory and translation and interpretation, a story to be told again and again in different ways. To wit: in 2020, Square began publishing a crazily expansive re-imagining of Final Fantasy VII, to be released as a trilogy of games rather than a single one. The first entry in the trilogy — the only one available as of this writing — gets the gang only as far as their departure from Midgar. By all indications, this first part has been a solid commercial success, although not a patch on the phenomenon its inspiration was in a vastly different media ecosystem.

As for me, coming to this game so many years later, bereft of all those personal connections to it: I’m happy I played it, happy to have familiarized myself with one of the most important videogames in history, and happy to have found a way to more or less enjoy it, even if I did have to break my usual rules to do so. I wouldn’t call myself a JRPG lover by any means, but I am JRPG curious. I can see a lot of potential in the game I played, if it was tightened up in the right ways. I look forward to giving Final Fantasy VIII a try; although it’s widely regarded as one of the black sheep of the Final Fantasy family, it seems to me that some of the qualities widely cited as its failings, such as its more realistic, less anime-stylized art, might just strike my aesthetic sensibilities as strengths. And I understand that Square finally got its act together and sprang for proper, professional-quality English translations beginning with this installment, so there’s that.

Now, to do something about those Haruki Murakami novels on my shelf…

Where to Get It: The original version of Final Fantasy VII can still be purchased from Steam as a digital download. If you’re an impatient curmudgeon like me, you may also want to install the 7th Heaven mod manager to tweak the game to your liking. For the record, the mods I wound up using were “OST Music Remastered” (for better music), “Echo-S 7” (for the better translation and voice acting), and “Gameplay Tweaks — Qhimm Catalog” (strictly to make my characters “always run”; I left everything else here turned off). With 7th Heaven alone installed, you can toggle random encounters off and on by pressing CONTROL-B while playing. Note that you need to do this each time you start the game up again.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The game’s tireless fan base has gone to great lengths, here as in so many places, to mitigate its failings by upping the difficulty in various ways. I didn’t investigate much in this area, deciding I had already given the game the benefit of enough retro-fitting with the mods I did employ. |

|---|