It seems poetically apt that Peter Adkison first met Richard Garfield through Usenet. For Magic: The Gathering, the card game that resulted from that meeting, went on to usher in a whole new era of tabletop gaming, during which it became much more tightly coupled with digital spaces. The card game’s rise did, after all, coincide with the rise of the World Wide Web; Magic sites were among the first popular destinations there. The game could never have exploded so quickly if it had been forced to depend on the old-media likes of Dragon magazine to spread the word, what with print publishing’s built-in lag time of weeks or months.

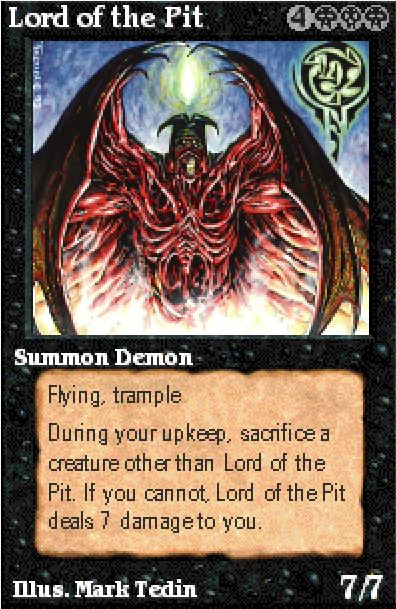

But ironically, computers could all too easily also be seen as dangerous to the immensely profitable business Wizards of the Coast so speedily became. So much of the allure of Magic was that of scarcity. A rare card like, say, a Lord of the Pit was an awesome thing to own not because it was an automatic game-winner — it wasn’t that at all, being very expensive in terms of mana and having a nasty tendency to turn around and bite you instead of your opponent — but because it was so gosh-darned hard to get your hands on. Yet computers by their very nature made everything that was put into them abundant; here a Lord of the Pit was nothing but another collection of ones and zeroes, as effortlessly copyable as any other collection of same. Would Magic be as compelling there? Or, stated more practically if also more cynically, what profit was to be found for Wizards of the Coast in putting Magic on computers? If they made a killer Magic implementation for the computer, complete with Lords of the Pit for everyone, would anyone still want to play the physical card game? In the worst-case scenario, it would be sacrificing an ongoing revenue stream to die for in return for the one-time sales of a single boxed computer game.

Had it been ten years later, Wizards of the Coast might have been thinking about setting up an official virtual community for Magic, with online duels, tournaments, leader boards, forums, perhaps even a card marketplace. As it was, though, it was still the very early days of the Web 1.0, when most sites consisted solely of static HTML. Online play in general was in its infancy, with most computer games that offered it being designed to run over local-area networks rather than a slow and laggy dial-up Internet connection. In this technological milieu, then, a Magic computer game necessarily meant a boxed product that you could buy, bring home, install on a computer that may or may not even be connected to the Internet, and play all by yourself.

That last part of the recipe introduced a whole host of questions and challenges beyond the strictly commercial. Think again about the nature of Magic: a fairly simple game in itself, but one that could be altered in an infinity of ways by the instructions printed on the cards themselves. Making hundreds and hundreds of separate cards play properly on the computer would be difficult enough. And yet that wasn’t even the worst of it: the really hard part would be teaching the computer to use its millions of possible combinations of cards effectively against the player, in an era before machine learning and the like were more than a glint in a few artificial-intelligence theorists’ eyes.

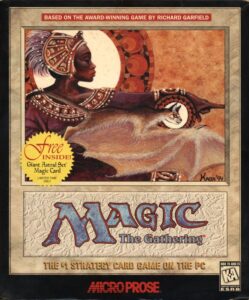

But to their credit, Wizards of the Coast didn’t dismiss the idea of a Magic computer game out of hand on any of these grounds. When MicroProse Software came calling, promising they could make it happen, Wizards listened and agreed to let them take a stab at it.

It so happened that Magic had caught the attention of MicroProse’s star designer, Sid Meier of Pirates!, Railroad Tycoon, and Civilization fame. This was unsurprising in itself; Meier was a grizzled veteran of many a tabletop war, who still kept a finger on the pulse of that space. Although he was never a dedicated player of the card game, he was attracted to Magic precisely because it seemed so dauntingly difficult to implement on a computer. Meier was, you see, a programmer as well as a designer, one with a strong interest in artificial intelligence, who had in fact just spent a year or more trying to teach a 3DO console to create music in the mold of his favorite classical composer, Johann Sebastian Bach. In his memoir, he frames his interest in a Magic computer game as a way of placating the managers in the corner offices at MicroProse who were constantly pushing him and his colleagues in the trenches toward licensed properties. With Magic, he could have his cake and eat it too, pleasing the suits whilst still doing something he could get personally excited about. “It seemed prudent,” he writes dryly, “for us to choose the kind of license we liked before they assigned one to us.”

We cannot accuse MicroProse of thinking small when it came to Magic on the computer; they wound up creating not so much a game as a sort of all-purpose digital Magic toolkit. You could put together your dream deck in the “Deck Builder,” choosing from 392 different cards in all. Then you could take the deck you built into the “Duel” program, where you could participate in a single match or in a full-on tournament against computer opponents. If all of this left you confused, you could work your way through a tutorial featuring filmed actors. Or, last but by no means least, you could dive into Shandalar, which embedded the card game into a simple CRPG format, in which Magic duels with the monsters that roamed the world took the place of a more conventional combat engine and improving your deck took the place of improving your character’s statistics. Suffice to say that MicroProse’s Magic did not lack for ambition.

Like the cheesy advisors in the otherwise serious-minded Civilization II, the tutorial that uses clips of real actors dates the MicroProse Magic indelibly to the mid-1990s. The actress on the left is Rhea Seehorn, whose long journeyman’s career blossomed suddenly into fame and Emmy awards in 2015, when she began playing Kim Wexler in the acclaimed television series Better Call Saul.

Doubtless for this reason, it took an inordinately long time to make. The first magazine previews of the computer game, describing most of the features that would make it into the finished product, appeared in the spring of 1995, just as the craze for the card game was nearing its peak. Yet the finished product wasn’t released until March of 1997, by which point the frenzy was already beginning to cool off, as Magic slowly transformed into what it still is today: “just” an extremely popular card game. “This is the end of a long journey,” wrote Richard Garfield in his foreword to the computer game’s manual, a missive that exudes relief and exhaustion in equal measure.

In fact, by the time MicroProse and Garfield completed the journey a whole different digital Magic game had been started and completed by a different studio. Acclaim Entertainment’s Magic: The Gathering — Battlemage was Wizards of the Coast’s attempt to hedge their bets when the MicroProse project kept stretching out longer and longer. At the surface level, Battlemage played much like Shandalar: you wandered a fantasy world collecting cards and dueling with enemies. But its duels were far less ambitious; rather than trying to implement the real card game in nitty-gritty detail, it moved its broadest strokes only into a gimmicky real-time framework, with a non-adjustable clock that just so happened to run way too fast. “By the time [you] manage to summon one creature,” wrote Computer Gaming World in its review, “the enemy has five or six on the attack.” This, the very first Magic computer game to actually ship, is justifiably forgotten today.

Then, too, by the time MicroProse’s Magic appeared Sid Meier had been gone from that company for nine months already, having left with his colleagues Jeff Briggs and Brian Reynolds to form a new studio, Firaxis Games. In his memoir, he speaks to a constant tension between MicroProse, who just wanted to deliver the funnest possible digital implementation of Magic, and Wizards of the Coast, who were worried about destroying their cash cow’s mystique. “I was frustrated,” he concludes. “Magic was a good computer game, but not as good as it could be.”

I concur. The MicroProse Magic is a good game — in fact, a well-nigh miraculous achievement when one considers the technological times in which it was created. Yet Shandalar in particular is a frustrating case: a good game that, one senses, just barely missed being spectacular.

But without a doubt, the most impressive thing about this Magic is that it works at all. The interface is a breeze to use once you grasp its vagaries, the cards all function just as they should in all of their countless nuances, and the computer actually does make a pretty credible opponent most of the time, capable of combining its cards in ingenious ways that may never have occurred to you until you get blasted into oblivion by them. Really, I can’t say enough about what an incredible programming achievement this is. Yes, familiarity may breed some contempt in the course of time; you will eventually notice patterns in some of your opponents’ play that you can exploit, and the computer players will do something flat-out stupid every once in a while. (Then again, isn’t that true of a human player as well?) Early reviewers tended to understate the quality of the artificial intelligence because it trades smarts for speed on slower computers, not looking as far ahead in its calculations. These days, when some of our toasters probably have more processing power than the typical 1997 gaming computer, that isn’t a consideration.

The MicroProse game even manages to implement cards like Magic Hack, which lets you alter the text(!) found on other cards.

Meanwhile Shandalar is a characteristic stroke of genius from Sid Meier, who was crazily good at translating lived experiences of all sorts into playable game mechanics. As we saw at length in the last article, it was the meta-game of collecting cards and honing decks that turned the card game into a way of life for so many of its players. Shandalar transplants this experience into a procedurally-generated fantasy landscape, capturing in the process the real heart of its analog predecessor’s appeal in a way that the dueling system on its own never could have, no matter how beautifully implemented. You start out as a callow beginner with a deck full of random junk, just like someone who has just returned from a trip to her friendly local game store with her first Magic Starter Pack. Your objective must now be to improve your deck into something you can win with on a regular basis, whilst learning how to use the cards you’ve collected most effectively and slowly building a reputation for yourself. Again, just like in real life.

The framing story has it that you are trying to protect the world of Shandalar from five evil wizards — one for each of the Magic colors — who are vying with one another and with you to take it over. You travel between the many cities and towns, buying and selling cards in their marketplaces and doing simple quests for their inhabitants that can, among other things, add to your dueling life-point total, which is just ten when starting out. Enemies in the employ of the wizards wander the same paths you do with decks of their own. Defeat them, and you can win one of their cards for yourself; get defeated by them, and you lose one of your own cards. (Shandalar is the last Magic product to use the misbegotten ante rule that the Wizards of the Coast of today prefers not to mention.)

After you’ve been at it a while, the other wizards’ lieutenants will begin attacking the towns directly. If any one enemy wizard manages to take over just three towns, he wins the game and you lose. (Unfortunately, the same lax victory conditions don’t apply to you…) Therefore it’s important not to let matters get out of hand on this front. You can rush to a town that’s being attacked and defend it by defeating the attacker in a duel, or you can even attack an already occupied town yourself in the hope of freeing it again, although this tends to be an even harder duel to win. When not thus occupied, you can explore the dungeons that are scattered about the map, stocked with tough enemies and tempting rewards in the form of gold, cards, and magical gems that confer special powers. Your ultimate goal, once you think you have the perfect deck, is to attack and defeat each wizard in his own stronghold; his strength in this final battle is determined by how many enemies of his color you’ve defeated elsewhere, so it pays to take your time. Don’t dawdle too long, though, because the other wizards get more and more aggressive about attacking towns as time goes by, which can leave you racing around willy-nilly trying to put out fire after fire, with scant time to take the offensive.

The MicroProse Magic was the first Sid Meier-designed game to appear in many years without the “Sid Meier’s…” prefix. His name was actually scrubbed from the credits completely, what with him having left the company before its completion. It was probably just as well: as he notes in his memoir, if MicroProse had tried to abide by its usual practice the game would presumably have needed to be called Sid Meier’s Wizards of the Coast’s Magic: The Gathering, which doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue.

You can reclaim towns that have been occupied by one of the enemy wizards, but it’s a risky battle, for which you must ante three cards to your opponent’s one.

All told, it’s a heck of a lot of fun, the perfect way to enjoy Magic if you don’t want to spend a fortune on cards and/or aren’t overly enamored with the culture of nerdy aggression that surrounds the real-life game to some extent even today. I spent way more time with Shandalar than I could really afford to as “research” for this article, restarting again and again to explore the possibilities of many different colors and decks and the variations in the different difficulty levels. Shandalar is great just as it is; I highly recommend it, and happily add it to my personal Hall of Fame.

And yet the fact is that the balance of the whole is a little off — not enough so as to ruin the experience, but just enough to frustrate when you consider what Shandalar might have been with a little more tweaking. My biggest beef is with the dungeons. They ought to be one of the best things about the game, being randomly generated labyrinths stocked with unusual opponents and highly desirable cards. Your life total carries over from battle to battle within a dungeon and you aren’t allowed to save there, giving almost a roguelike quality to your underground expeditions. It seems to be a case of high stakes and high rewards, potentially the most exciting part of the game.

It makes no sense to risk the dungeons when you can randomly stumble upon places on the world map that let you have your choice of any card in the entire game. Happy as you are when you find them, these places are devastating to game balance.

But it isn’t, for the simple reason that the rewards aren’t commensurate with the risks in the final analysis. Most of the time, the cards you find in a dungeon prove not to be all that great after all; in fact, you can acquire every single one of them above-ground in one way or another, leaving you with little reason to even enter a dungeon beyond sheer, bloody-minded derring-do. A whole dimension of the game falls away into near-pointlessness. Yes, you can attempt to compensate for this by, say, pledging not to buy any of the most powerful cards at the above-ground marketplaces, but why should you have to? It shouldn’t be up to you to balance someone else’s game for them.

Even looking beyond this issue, Shandalar just leaves me wanting a little more — a bigger variety of special encounters on the world map, more depth to the economy, more and more varied quests. This is not because what we have is bad, mind you, but because it’s so good. My problem is that I just can’t stop seeing how it could be even better, can’t help wondering how it might have turned out had Sid Meier stayed at MicroProse through the end of the project. Which isn’t to say that you shouldn’t try this game if you already enjoy the card game or are even slightly curious about it. The MicroProse Magic retains a cult following to this day, many of whom will tell you that Shandalar in particular is still the most fun you can have with Magic on a computer.

In its own time, however, the most surprising thing about the MicroProse Magic is that it wasn’t more commercially successful. “I’ve found a wonderful place to play Magic: The Gathering,” wrote Computer Gaming World in its review. “I can play as much as I want whenever I want, and use legendary cards like Black Lotus and the Moxes without spending hundreds of dollars.” Nevertheless, the package didn’t set the world on fire. Perhaps the substandard Acclaim game, which was released just a month before the MicroProse version, muddied the waters too much. Or perhaps even more of the appeal of the card game than anyone had realized lay in the social element, which no digital version in 1997 could possibly duplicate.

Not that MicroProse didn’t try. “This game is exceedingly expandable,” wrote Richard Garfield in his foreword in the manual, strongly implying that the MicroProse Magic was just the beginning of a whole line of follow-on products that would keep it up to date with the ever-evolving card game. But that didn’t really happen. MicroProse did release Spells of the Ancients, a sort of digital Booster Pack with some new cards, followed by a standalone upgrade called Duels of the Planeswalkers, with yet more new cards and the one feature that was most obviously missing from the original game: the ability to duel with others over a network, albeit without any associated matchmaking service or the like that could have fostered a centralized online community of players. Not long after Duels of the Planeswalkers came out in January of 1998, the whole line fell out of print, having never quite lived up to MicroProse’s expectations for it. Wizards of the Coast, for their part, had always seemed a bit lukewarm about it, perchance not least because Shandalar relied so heavily on the ante system which they were by now trying hard to bury deep, deep down in the memory hole. Their next foray into digital Magic wouldn’t come until 2002, when they set up Magic: The Gathering Online, precisely the dynamic online playing space I described as infeasible earlier in this article in the context of the 1990s.

I’ll have more to say about the Magic phenomenon in future articles, given that it was the fuel for the most shocking deal in the history of tabletop gaming. The same year that the MicroProse Magic game came out, a swaggering, cash-flush Wizards of the Coast bought a teetering, cash-strapped TSR, who had seen the market for Dungeons & Dragons all but destroyed by Richard Garfield’s little card game. This event would have enormous repercussions on virtual as well as physical desktops, occurring as it did just after Interplay Entertainment had been awarded the license to make the next generation of Dungeons & Dragons computer games.

For today, though, let me warmly recommend the MicroProse Magic — if you can see your way to getting it running, that is. (See below for more on that subject.) Despite my quibbles about the ways in which it could have been even better, Shandalar remains almost as addictive for me today as the card game was for so many teenagers of the 1990s, only far less expensively so. When I pulled it up again to capture screenshots for this article, I blundered into a duel and just had to see it out. Ditto the next one, and then the one after that. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Where to Get It: The MicroProse Magic: The Gathering is unfortunately not an easy game to acquire or get running; the former difficulty is down to the complications of licensing, which have kept it out of digital-download stores like GOG.com, while the latter is down to its status as a very early Windows 95 game, from before DirectX was mature and before many standards for ensuring backward compatibility existed. Because I’d love for you to be able to play it, though, I’ll tell you how I got it working. Fair warning: it does take a bit of effort. But you don’t need to be a technical genius to make it happen. You just have to take it slow and careful.

- First of all, you’re going to need a virtual machine running Windows XP. This is not as onerous an undertaking as you might expect. I recommend a video tutorial from TheHowToGuy123, which walks you step by step through installing the operating system under Oracle VirtualBox in a very no-nonsense way.

- Next you need an image of the Magic CD. As of this writing, a search for “Magic The Gathering MicroProse” on archive.org will turn one up. Note that these procedures assume you are installing the original game, not Duels of the Planeswalkers. The patches you install will actually update it to that version.

- Boot up your virtual Windows XP machine and mount the Magic image from the VirtualBox “Devices” menu. Ignore the warning about not being on Windows 95 and choose “Install” from the window that pops up. Take the default options and let it do its thing. Do not install DirectX drivers and do not watch the tutorial; it won’t work anyway.

- Now you need to patch the game — twice, in fact. You can download the first patch from this very site. Mount the image containing the patch in VirtualBox and open the CD drive in Windows Explorer. You’ll see three executable files there, each starting with “MTGV125.” Drag all three to your desktop, then double-click them from there to run them one at a time. You want to “Unzip” each into the default directory.

- Restart your virtual Windows XP machine.

- Now you need the second patch, which you can also get right here. Mount this disk image on your virtual machine, create a folder on its desktop, and copy everything in the image into that folder. Double-click “Setup” from the desktop folder and wait a minute or two while it does its thing.

- Now copy everything from that same folder on your desktop into “C:\Magic\Program,” selecting “Yes to All” at the first warning prompt to overwrite any files that already exist there. If you see an error message about open file handles or the like, restart your virtual machine and try again.

- Here’s where it gets a little weird. The “Shandalar” entry on your Start menu is no longer pointing to the Shandalar game, but rather to the multiplayer engine. Go figure. To fix this, navigate into “C:\Magic\Program,” find “shandalar.exe,” and make a shortcut to it on your desktop. Double-click this to play the game. If it complains about a lack of swap space, just ignore it and go on.

- You’ll definitely want the manual as well.

Shandalar, the Deck Builder, and the single-player Duel app should all work now. The first does still have some glitches, such as labels that don’t always appear in town menus, but nothing too devastating (he says, having spent an inordinate amount of time… er, testing it thoroughly). I haven’t tested multiplayer, but it would surprise me if it still works. Alas, the cheesily charming tutorial is a complete bust with this setup; you can watch it on YouTube if you like.

Note that this is just one way to get Magic running on a modern computer, the one that worked out for me. Back in 2010, a group of fans made a custom version that ran seamlessly under Windows 7 without requiring a virtual machine, but it’s my understanding that that version doesn’t work under more recent versions of the operating system. Sigh… retro-gaming in the borderlands between the MS-DOS and Windows eras is a bit like playing Whack-a-Mole sometimes. If you have any other tips or tricks, by all means, share them in the comments.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Sid Meier’s Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games by Sid Meier with Jennifer Lee Noonan; Computer Gaming World of June 1995, August 1996, May 1997, June 1997, and May 1998. And Soren Johnson’s interview with Sid Meier on his Designer Notes podcast.)