Warning: this article spoils the ending of Spycraft: The Great Game!

On January 6, 1994, Activision announced in a press release that it was “teaming up with William Colby, the former head of the Central Intelligence Agency, to develop and publish espionage-thriller videogames.” Soon after, Colby brought his good friend Oleg Kalugin into the mix as well. With the name-brand, front-of-the-box talent for Spycraft: The Great Game — and, if all went swimmingly, its sequels — thus secured, it was time to think about who should do the real work of making it.

Even as late as 1994, Activision’s resurrection from its near-death experience of 1991 was still very much a work in progress. The company was chronically understaffed in relation to its management’s ambitions. To make matters worse, much of the crew that had made Return to Zork, including that project’s mastermind William Volk, had just left. (On balance, this may not have been such a bad thing; that game is so unfair and obtuse as to come off almost as a satire of player-hostile adventure-game design.)

Luckily, Activision’s base in Los Angeles left it well situated, geographically speaking, to become a hotbed of interactive movie-making. Bobby Kotick hired Alan Gershenfeld, a former film critic and logistical enabler for Hollywood, to spearhead his efforts in that direction. Realizing that he still needed help with the interactive part of interactive movies, Gershenfeld in turn took the unusual step of reaching out to Bob Bates, co-founder of the Virginia-based rival studio and publisher Legend Entertainment, to see if he would be interested in designing Spycraft for Activision.

He was very interested. One reason for this was that Legend lived perpetually hand to mouth in a sea of bigger fish, and couldn’t afford to look askance at paying work of almost any description. But another, better one was that he was a child of the Washington Beltway with a father who had been employed by the National Security Agency. Bates had read his first spy novel before starting high school. Ever since, his literary consumption had included plenty of Frederick Forsyth, Robert Ludlum, and John Le Carré. It was thus with no small excitement that he agreed to spend 600 hours creating a script and design document for an espionage game, which Legend’s programmers and artists might also end up playing a role in bringing to fruition if all went well.

At this time, writers of espionage fiction and techno-thrillers were still trying to figure out what the recent ending of the Cold War meant for their trade. Authors like those Bates had grown up reading were trying out international terrorist gangs, mafiosi, and drug runners as replacements for that handy all-purpose baddie the Soviet Union. Activision faced the same problem with Spycraft. One alternative — the most logical one in a way, given the time spans of its two star advisors’ intelligence careers — was to look to the past, to make the game a work of historical fiction. But the reality was that there was little appetite for re-fighting the Cold War in the popular culture of the mid-1990s; that would have to wait until a little later, until the passage of time had given those bygone days of backyard fallout shelters and duck-and-cover drills a glow of nostalgia to match that of radioactivity. In the meanwhile, Activision wanted something fresh, something with the sort of ripped-from-the-headlines relevance that Ken Williams liked to talk about.

Bates settled on a story line involving Boris Yeltsin’s Russia, that unstable fledgling democracy whose inheritance from the Soviet Union encompassed serious organized-crime and corruption problems along with the ongoing potential to initiate thermonuclear Armageddon any time it chose to do so. He prepared a 25,000-word walkthrough of a plot whose broad strokes would survive into the finished game. Changing the names of all of the real-world leaders involved in order to keep the lawyers at bay, it hinged around a race for the Russian presidency involving a moderate, Yeltsin-like incumbent and two right-wing opposition candidates. When one of the latter is assassinated, it redounds greatly to the benefit of his counterpart; the two right-wingers had otherwise looked likely to split the vote between themselves and hand the presidency back to the incumbent. So, there are reasons for suspicion from the get-go, and the surviving opposition candidate’s established ties with the Russian Mafia only gives more reasons. That said, it would presumably be a matter for Russia’s internal security police alone — if only the assassination hadn’t been carried out with an experimental CIA weapon, a new type of sniper rifle that can fire a deadly accurate and brutally lethal package of flechettes over long distances. It seems that there is a mole in the agency, possibly one with an agenda to incriminate the United States in the killing.

On the one hand, one can see in this story line some of the concerns that William Colby and Oleg Kalugin were expressing in the press at the time. On the other, they were hardly alone in identifying the instability of internal political Russia as a threat to the whole world, what with that country’s enormous nuclear arsenal. Bates himself says that he quickly realized that Activision was content to use Colby and Kalugin essentially as a commercial license, much like it would a hit movie or book. In the more than six months that he worked on Spycraft, he met Colby in person only one time, at his palatial Georgetown residence. (“It was clear that he was wealthy. He was very old-school. Circumspect, as you might imagine.”) Kalugin he never met at all. Fortunately, Legend’s niche in recent years had become the adaptation of commercial properties into games, and thus Bates had become very familiar with playing in other people’s universes, as it were. The milieu inhabited by Colby and Kalugin, as described by the two men in their memoirs, became in an odd sort of way just another of these pocket universes.

In other ways, however, Bates proved less suited to the game Activision was imagining. He was as traditionalist as adventure-game designers came, having originally founded Legend with the explicit goal of making it the heir to Infocom’s storied legacy. Activision’s leadership kept complaining that his design was not exciting enough, not “explosive” enough, too “tame.” To spice it up, they brought in an outside consultant named James Adams, a British immigrant to the United States who had written seven nonfiction books on the worlds of espionage and covert warfare along with three fictional thrillers. In the early fall of 1994, Bates, Adams, and some of Activision’s executives had a conversation which is seared on Bates’s memory like nothing else involving Spycraft.

They were saying it wasn’t intense or exciting enough. We were just kicking around ideas, and as a joke I said, “Well, we could always do a torture scene.”

And they said, “Yes! Yes!”

And I said, “No! No! I’m kidding. We’re not going to do that.”

And they said, “Yes, we really want to do that.”

And I said, “No. I am not putting the player in a position where they have to commit an act of torture. I just won’t do that.” At that point, the most violent thing I’d ever put into a game was having a boar charge onto a spear in Arthur…

Shortly after this discussion, Bates accepted Activision’s polite thanks for his contributions along with his paycheck for 600 hours of his time, and bowed out to devote himself entirely to Legend’s own games once again. Neither he nor his company had any involvement with Spycraft after that. His name doesn’t even appear in the finished game’s credits.

James Adams now took over full responsibility for the convoluted script, wrestling it into shape for production to begin in earnest by the beginning of 1995. The final product was released on Leap Day, 1996. It isn’t the game Bates would have made, but neither is it the uniformly thoughtless, exploitive one he might have feared its becoming when he walked away. What appears for long stretches to be a rah-rah depiction of the CIA — exactly what you might expect from a game made in partnership with one of the agency’s former directors — betrays from time to time an understanding of the moral bankruptcy of the spy business that is more John Le Carré than Ian Fleming. In the end, it sends you away with a distinctly queasy feeling about the things you’ve done and the logic you’ve used to justify them. All due credit goes to James Adams for delivering a game that’s more subtle than the one Activision — and probably Colby and Kalugin as well — thought they were getting.

But let’s table that topic for the moment, while I first go over the ways in which Spycraft also succeeds in being an unusually fun interactive procedural, the digital equivalent of a page-turning airport read.

Being a product of its era, Spycraft relies heavily on canned video clips of real actors. It’s distinguished, however, by the unusual quality of same, thanks to what must have been a substantial budget and to the presence of movie-making veterans like Alan Gershenfeld on Activision’s payroll. It was Gershenfeld who hired Ken Berris, an experienced director of music videos and commercials, to run the video shoots; he may not have been Steven Spielberg, but he was a heck of a lot more qualified than most people who fancied themselves interactive-movie auteurs. Most of those other games were shot like the movies of the 1930s, with the actors speaking their lines on a static sound stage before a fixed camera. Berris, by contrast, has seen Citizen Kane; he mostly shoots on location rather than in front of green screens that are waiting to be filled in with computer graphics later, and his environments are alive, with a camera that moves through them. Spycraft‘s bravura opening sequence begins with a single long take shown from your point of view as you sign in at CIA headquarters and walk deeper into the building. I will go so far as to say that this painstakingly choreographed and shot high-wire act, involving several dozen extras moving through a space along with the camera and hitting their marks just so, might be the most technically impressive live-action video sequence I’ve ever seen in a game. It wouldn’t appear at all out of place in a prestige television show or a feature film. Suffice to say that it’s light years beyond the hammy amateurism of something like The 7th Guest, a sign of how far the industry had come in only a few years, just before the collapse of the adventure market put an end to the era of big-budget live-action interactive movies for better or for worse.

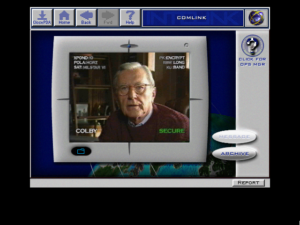

There are no stars among the journeyman cast of supporting players, but there are at least a few faces and voices that might ring a bell somewhere at the back of your memory, thanks to their regular appearances in commercials, television shows, and films. Although some of the actors are better than others, by the usual B-movie standards of the 1990s games industry the performances as a whole are first rate. Both William Colby and Oleg Kalugin also appear in the game, playing themselves. Colby becomes an advisor of sorts to you, popping up from time to time to offer insights on your investigations; Kalugin has only one short and rather pointless cameo, dropping into the office for a brief aside when you’re meeting with another agent of Russia’s state-security apparatus. Both men acquit themselves unexpectedly well in their roles, undemanding though they may be. I can only conclude that all those years of pretending to be other people while engaged in the espionage trade must have been good training for acting in front of a camera.

You play a rookie CIA agent who is identified only as “Thorn.” You never actually appear onscreen; everything is shown from your first-person perspective. Thus you can imagine yourself to be of any gender, race, or appearance that you like. Spycraft still shows traces of the fairly conventional adventure-game structure it would doubtless have had if Bob Bates had continued as its lead designer: you have an inventory that you need to dig into from time to time, and will occasionally find yourself searching rooms and the like, using an interface not out of keeping with that found in Legend’s own contemporaneous graphic adventures, albeit built from still photographs rather than hand-drawn pixel art.

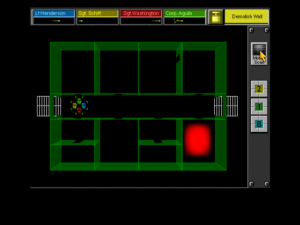

But those parts of the game take up a relatively small part of your time. Mostly, Thorn lives in digital rather than meat space, reading and responding to a steady stream of emails, poking around in countless public and private databases, and using a variety of computerized tools that have come along to transform the nature of spying since the Cold War heyday of Colby and Kalugin. These tools — read, “mini-games” — take the place of the typical adventure game’s set-piece puzzles. In the course of playing Spycraft, you’ll have to ferret out license-plate numbers and the like from grainy satellite images; trace the locations of gunmen by analyzing bullet trajectories (this requires the use of the aptly named “Kennedy Assassination Tool”); identify faces captured by surveillance cameras; listen to phone taps; decode secret messages hidden in Usenet post headers; doctor photographs; trace suspects’ travels using airline-reservation systems and Department of Treasury banknote databases; even run a live exfiltration operation over a digital link-up.

The tactical exfiltration mini-game is the most ambitious of them all, reminding me of a similar one in Sid Meier’s Covert Action, another espionage game whose design approach is otherwise the exact opposite of Spycraft‘s. It’s good enough that I kind of wish it was used more than once.

These mini-games serve their purpose well. If most of them are too simplistic to be very compelling in the long term, well, they don’t need to be; most of them only turn up once. Their purpose is to trip you up just long enough to give you a thrill of triumph when you figure them out and are rocketed onward to the next plot twist. Spycraft is meant to be an impressionistic thrill ride, what Rick Banks of Artech Digital Productions liked to call an “aesthetic simulation” back in the 1980s. If you find yourself complaining that you’re almost entirely on rails, you’re playing the wrong game; the whole point of Spycraft is the subjective experience of living out a spy movie, not presenting you with “interesting decisions” of the sort favored by more purist game designers like Sid Meier.

In Spycraft, you roam a simulated version of cyberspace using a Web-browser interface, complete with “Home,” “Back,” and “Forward” buttons — a rather remarkable inclusion, considering how new the very notion of browsing the Web still was when this game was released in February of 1996. The game even included a real online component: some of the sites you could access through the games received live updates if your computer was connected to the real Internet. Thankfully, nothing critical to completing the game was communicated in this way, for these sites are all, needless to say, long gone today.

As is par for the course with spy stories, the plot just keeps getting more and more tangled, perchance too much so for its own good. Just in case the murder of a Russian presidential candidate with a weapon stolen from the CIA isn’t enough for you, other threads eventually emerge, involving a gang of terrorists who are attempting to secure a live nuclear bomb and a plan to assassinate the president of the United States when he comes to Russia to sign a nuclear-arms-control agreement. You’re introduced to at least 50 different names, many of them with multiple aliases — again, this is a spy story — in the handful of hours it will take you to play the game. The fact that you spend most of your time at such a remove from them — shuffling through their personnel files and listening to them over phone taps rather than meeting them face to face — only makes it that much harder to keep them all straight, much less feel any real emotional investment in them. There are agents, double agents, triple agents, and, I’m tempted to say, quadruple agents around every corner.

I must confess that I really have no idea how well it all hangs together in the end. Just thinking about it makes my head hurt. I suppose it doesn’t really matter all that much; as I said, there’s only one path through the game, with minimal deviations allowed. Should you ever feel stuck, forward progress is just a matter of rummaging around until you find that email you haven’t read yet, that phone number you haven’t yet dialed, or that mini-game you haven’t yet completed successfully. Spycraft never demands that you understand its skein of conspiracies and conspirators, only that you jump through the series of hoops it sets before you in order to help your alter ego Thorn understand it. And that’s enough to deliver the impressionistic thrill ride it wants to give you.

The plot is as improbable as it is gnarly, making plenty of concessions to the need to entertain; it strains credibility to say the least that a rookie agent would be assigned to lead three separate critical investigations at the same time. And yet the game does demonstrate that it knows a thing or two about the state of the world. Indeed, it can come across as almost eerily prescient today, and not only for its recognition that a hollowed-out Russia with an aggressively revanchist leader could become every bit as great a threat to the democratic West as the Soviet Union once was. It also recognizes what an incredible tool for mass surveillance and oppression the Internet and other forms of networked digital technology were already becoming in 1996, seventeen years before the stunning revelations by Edward Snowden about the activities of the United States’s own National Security Agency. And then there is the torture so unwittingly proposed by Bob Bates, which did indeed make it into the game, some seven years before the first rumors began to emerge that the real CIA was engaging in what it called “enhanced interrogation techniques” in the name of winning the War on Terror.

Let’s take a moment now to look more closely at how Spycraft deals with this fraught subject in particular. Doing so should begin to show how this game is more morally conflicted than its gung-ho surface presentation might lead you to expect.

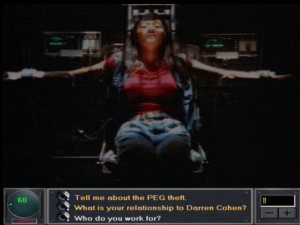

Let me first make one thing very clear: you don’t have to engage in torture to win Spycraft. This is one of the few places where you do have a measure of agency in choosing your path. The possibility of employing torture as a means to your ends is introduced about a third of the way into the game, after your colleagues have captured one Ying Chungwang, a former operative for North Korea, now a mercenary on the open market who has killed several CIA agents at the behest of various employers. She’s the Bonnie to another rogue operative’s Clyde. Your superiors suggest that you might be able to turn her by convincing her that her lover has also been captured and has betrayed her; this you can do by making a fake photograph of him looking relaxed and cooperative in custody. But there may also be another way to turn her, a special gadget hidden in the basement of the American embassy in Moscow, involving straps, electrodes, and high-voltage wiring. Most of your superiors strongly advise against using it: “There’s something called the Geneva Convention, Thorn, and we’d like to abide by it. Simply put, what you’re considering is illegal. Let’s not get dirty on this one.” Still, one does have to wonder why they keep it around if they’re so opposed to it…

Coincidentally or not, the photo-doctoring mini-game is easily the most frustrating of them all, an exercise in trial and error that’s made all the worse by the fact that you aren’t quite sure what you’re trying to create in the first place. You might therefore feel an extra temptation to just say screw it and head on down to the torture chamber. If you do, another, more chilling sort of mini-game ensues, in which you must pump enough electric current through your victim to get her to talk, without turning the dial so high that you kill her. “It burns!” she screams as you twist the knob. If you torture like Goldilocks — not too little, not too much — she breaks down eventually and tells you everything you want to know. And that’s that. Nobody ever mentions what happened in that basement again.

What are we to make of this? We might wish that the game would deliver Thorn some sort of comeuppance for this horrid deed. Maybe Ying could give you bad intelligence just to stop the pain, or you could get automatically hauled away to prison as soon as you leave the basement, as does happen if you kill her by using too much juice. But if there’s one thing we can learn from the lives of Colby and Kalugin, it’s that such an easy, cause-and-effect moral universe isn’t the one inhabited by spies. Yes, torture does often yield bad intelligence; in the 1970s, Colby claimed this was a reason the CIA was not in the habit of using it, a utilitarian argument which has been repeated again and again in the decades since to skeptics who aren’t convinced that the agency’s code of ethics alone would be enough to cause it to resist the temptation. Yet torture is not unique in being fallible; other interrogation techniques have weaknesses of their own, and can yield equally bad intelligence. The decision to torture or not to torture shouldn’t be based on its efficacy or lack thereof. Doing so just leads us back to the end-justifies-the-means utilitarianism that permitted the CIA and the KGB to commit so many outrages, with the full complicity of upstanding patriots like Colby and Kalugin who were fully convinced that everything they did was for the greater good. In the end, the decision not to torture must be a matter of moral principle if we are ever to trust the people making it.

Then again, if you had hold of an uncooperative member of a terrorist cell that was about to detonate an atomic bomb in a major population center, what would you do? This is where the slippery slope begins. The torture scene in Spycraft is deeply disturbing, but I don’t think that James Adams put it there strictly for the sake of sensationalism. Ditto the lack of consequences that follow. In the real world, virtue must often be its own reward, and the wages of sin are often a successful career. I think I’m glad that Spycraft recognizes this and fails to engage in any tit-for-tat vision of temporal justice — disturbed, yes, but oddly proud of the game at the same time. I’m not sure that I would have had the guts to put torture in there myself, but I’m convinced by some of the game’s other undercurrents that it was put there for purposes other than shock value. (Forgive the truly dreadful pun…)

Let’s turn the clock back to the very beginning of the game for an example. The first thing you see when you click the “New Game” button is the CIA’s official Boy Scout-esque values statement: “We conduct ourselves according to the highest standards of integrity, morality, and honor, and to the spirit and letter of our law and constitution.” Meanwhile a gruffer, more cynical voice is telling you how it really is: “Some things the president shouldn’t know. For a politician, ignorance can be the key to survival, so the facts might be… flexible. The best thing you can do is to treat your people right… and watch every move they make.” It’s a brilliant juxtaposition, culminating in the irony that is the agency’s hilariously overwrought Biblical motto: “And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” And then we’re walking into CIA headquarters, an antiseptic place filled with well-scrubbed, earnest-looking people, and that note of moral ambiguity is forgotten for the nonce as we “build the team” for a new “op.”

But as you play on, the curtain keeps wafting aside from time to time to reveal another glimpse of an underlying truth that you — or Thorn, at least — may not have signed on for. One who has seen this truth and not been set free is a spy known as Birdsong, a mole in the Russian defense establishment who first started leaking secrets to the CIA because he was alarmed by some of his more reactionary colleagues and genuinely thought it was the right thing to do. He gets chewed up and spit out by both sides. “I can tell the truth from lies no more,” he says in existential despair. “Everything is blurry. This has been hell. Everyone has betrayed me and I have betrayed everyone.” Many an initially well-meaning spy in the real world has wound up saying the same.

And then — and most of all — there’s the shocking, unsatisfying, but rather amazingly brave ending of the game. By this point, the plot has gone through more twists and turns than a Klein bottle, and the CIA has decided it would prefer for the surviving Russian opposition candidate to win the election after all, because only he now looks likely to sign the arms-control treaty that the American president whom the CIA serves so desperately desires. Unfortunately, one Yuri, a dedicated and incorruptible Russian FSB agent who has been helping you throughout your investigations, is still determined to bring the candidate down for his entanglements with the Russian Mafia. In the very last interactive scene of the game, you can choose to let Yuri take the candidate into custody and uphold the rule of law in a country not much known for it, which will also result in the arms-control agreement failing to go through and you getting drummed out of the CIA. Or you can shoot your friend Yuri in cold blood, allowing the candidate to become the new president of Russia and escape any sort of reckoning for his crimes — but also getting the arms-control agreement passed, and getting yourself a commendation.

As adventure-game endings go, it’s the biggest slap in the face to the player since Infocom’s Infidel, upending her moral universe at a stroke. It becomes obvious now, if we still doubted it, that James Adams appreciates very well the perils of trying to achieve worthy goals by unworthy means. Likewise, he appreciates the dangers that are presented to a free society by a secretive institution like the CIA — an arrogant institution, which too often throughout its history has been convinced that it is above the moral reckoning of tedious ground dwellers. Perhaps he even sees how a man like William Colby could become a reflection of the agency he served, could be morally and spiritually warped by it until it had cost him his family and his faith. “Uniquely in the American bureaucracy,” wrote Colby in his memoir, “the CIA understood the necessity to combine political, psychological, and paramilitary tools to carry out a strategic concept of pressure on an enemy or to strengthen an incumbent.” When you begin to believe that only you and “your” people are “uniquely” capable of understanding anything, you’ve started down a dangerous road indeed, one that before long will allow you to do almost anything in the name of some ineffable greater good, using euphemisms like “pressure” in place of “assassinate,” “strengthen an incumbent” in place of “interfere in a sovereign foreign country’s elections” — or, for that matter, “enhanced interrogation techniques” in place of “torture.”

Spycraft is a fascinating, self-contradictory piece of work, slick but subversive, escapist but politically aware, simultaneously carried away by the fantasy of being a high-tech spy with gadgets and secrets to burn and painfully aware of the yawning ethical abyss that lies at the end of that path. Like the trade it depicts, the game sucks you in, then it repulses you. Nevertheless, you should by all means play it. And as you do so, be on the lookout for the other points of friction where it seems to be at odds with its own box copy.

Spycraft wasn’t a commercial success. It arrived too late for that, at the beginning of the year that rather broke the back of interactive movies and adventure games in general. Thus the Spycraft II that is boldly promised during the end credits never appeared. Luckily, Activision was in a position to absorb the failure of their conflicted spy game. For the company was already changing with the times, riding high on the success of Mechwarrior 2, a 3D action game in which you drive a giant robot into combat. “How about a big mech with an order to fry?” ran its tagline; this was the very definition of pure escapism. Mainstream gaming, it turned out, was not destined to be such a ripped-from-the-headlines affair after all.

I do wonder sometimes whether Colby and Kalugin ever knew what a bleak note their one and only game ended on. Somehow I suspect not. It was, after all, just another business deal to them, another way of cashing in on the careers they had put behind them. Their respective memoirs tell us that both were very, very smart men, but neither comes across as overly introspective. I’m not sure they would even recognize what a telling commentary Spycraft‘s moral bleakness is on their own lives.

It was just two months after the game’s release that William Colby disappeared from his vacation home. When his body turned up on May 6, 1996, those few people who had both bought the game and been following the manhunt were confronted with an eyebrow-raising coincidence. For it just so happens that the CIA’s flechette gun isn’t the only experimental weapon you encounter in the course of the game. Later on, an even more devious one turns up, a sort of death ray that can kill its victims without leaving a mark on them — that causes them to die from what appears to be a massive coronary arrest. The coroner who examined Colby’s body insisted that he must have had a “cardiovascular incident,” despite having no previous history of heart disease. Hmm…

The case of Colby’s demise has never been officially reopened, but one more theory has been added to those of death by misadventure and death by murder since 1996. His son Carl Colby, who made a documentary film about his father in 2011, believes that he took his own life purposefully. “I think he’d had enough of this life,” he reveals at the end of his film. “He called me two weeks before he died, asking for my absolution for his not doing enough for my sister Catherine when she was so ill. When his body was found, he was carrying a picture of my sister.” In a strange way, it does seem consistent with this analytical, distant man, for whom brutal necessities were a stock in trade, to calmly eat his dinner, get into his canoe, paddle out from shore, and drown himself.

Oleg Kalugin, on the other hand, lived on. Russia’s new President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB agent himself, opened a legal case against Kalugin shortly after he took office, charging him with “disclosing sources and methods” in his 1994 memoir that he had sworn an oath to keep secret. Kalugin was already living in the United States at that time, and has not dared to return to his homeland since. From 2002, when a Russian court pronounced him guilty as charged, he has lived under the shadow of a lengthy prison sentence, or worse, should the Russian secret police ever succeed in taking him into custody. In light of the fate that has befallen so many other prominent critics of Russia’s current regime, one has to assume that he continues to watch his back carefully even today, at age 88. You can attempt to leave the great game, but the great game never leaves you.

(Sources: the book Game Plan by Alan Gershenfeld, Mark Loparco, and Cecilia Barajas; the documentary film The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby; Sierra On-Line’s newsletter InterAction of Summer 1993; Questbusters of February 1994; Electronic Entertainment of December 1995; Mac Addict of September 1996; Next Generation of February 1996; Computer Gaming World of July 1996; New York Times of January 6 1994 and June 27 2002. And thanks as always to Bob Bates for taking the time to talk to me about his long career in games.

Spycraft: The Great Game is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.)