The telegraph networks of the late nineteenth century functioned much like the railroad networks with which they were so closely associated in the minds of the public. Each pair of Morse keys and receivers was connected to exactly one other pair via a fixed “track.” Messages traveled from station to station through the network like railroad passengers. A telegram sent from Smalltown, USA, would first be sent up the line to a larger hub station, where it would be dropped into the “outgoing” basket of another line connected to the same station that would take it to its next stop. And so on and so on, until it reached its final destination.

But the telephone wasn’t conducive to this approach. Alexander Graham Bell’s dream of being “able to chat pleasantly with friends in Europe while sitting in his Boston home” would require a different sort of network model, one more akin to the roads that would soon be built to handle automobile traffic. It would need to be possible for a message to steer its own way down a multitude of highways and byways to reach one of thousands or millions of individual addresses accessible on the network. And each message would need to do so at the same time that many other messages were doing the same thing, using the same roads. Network engineers would never again have it so easy as they had in the days when the telegraph was the only game in town.

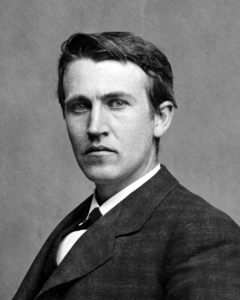

Indeed, in contrast to this puzzle of dynamic routing, the invention of the telephone itself would soon seem a fairly minor challenge to have overcome. This new problem was too difficult, diffuse, and abstract to be solved in one eureka moment, or even a dozen of them. The worldwide telecommunications network that came into existence by the middle of the twentieth century was instead the result of steady incremental progress over the course of the decades, guided by people whose names have not found a place in history textbooks alongside those of Samuel Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, and Thomas Alva Edison. Yet the worldwide web these institutional inventors slowly pieced together was in its way more remarkable than any of the aforementioned men’s discrete creations. And it was also both the necessary precursor to and the medium of the computer-communications networks that would follow in the second half of the twentieth century.

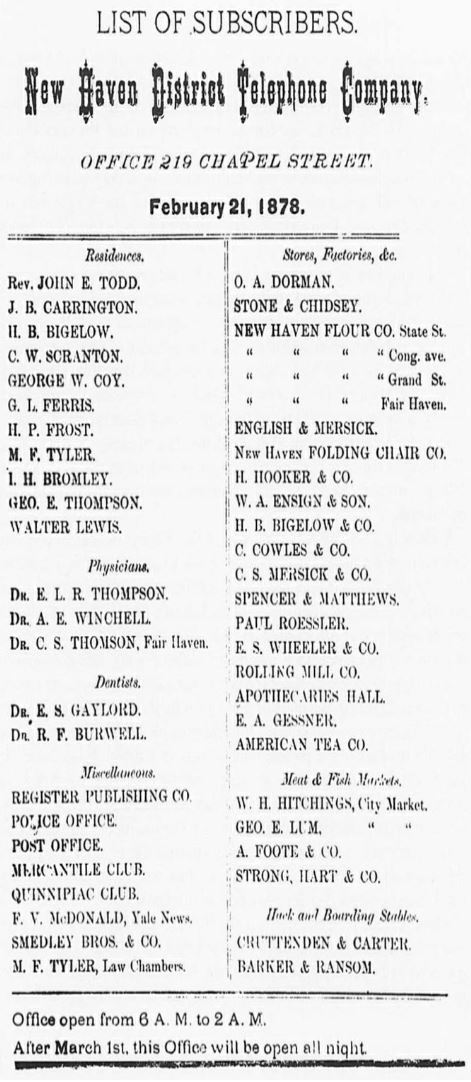

The New Haven District Telephone Company’s exchange was the first of its type, heralding as much as the telephone itself a new era in communications.

The first system for letting any one telephone on a large network communicate with any other came into being in New Haven, Connecticut, on January 28, 1878. It was operated by the New Haven District Telephone Company, a spinoff of Bell Telephone, and connected 21 founding subscribers using a very simple, very physical method. The wire from each telephone on the network ran to a central exchange manned by a human operator. When you picked up your home phone to make a call, you were thus immediately connected to this individual. You told him which other subscriber you wished to speak to — the concept of phone numbers did not yet exist — whereupon he cranked a magneto to cause a bell to ring at the other end of your desired interlocutor’s line. If the individual in question picked up, the operator then linked your two telephones together using a patch cable.

It may strike us as a crude arrangement today. Certainly it was beset by obvious practical problems (what happened when more people tried to make calls than the operator could handle?) and privacy concerns (the operator could tell if a call was finished only by periodically listening in). Yet it spread like wildfire in lieu of any alternatives. The world’s second telephone exchange opened just three days after its first; by the end of 1878 there were several dozen of them in the United States, and a ringer had become an essential piece of telephony’s standard equipment. By the beginning of 1881, there were only nine cities with a population over 10,000 in the United States which didn’t boast at least one telephone exchange.

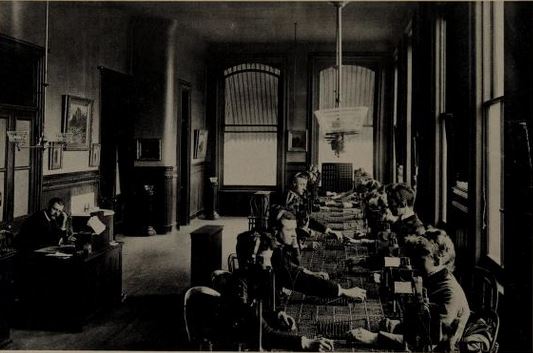

An early telephone exchange manned by boys, circa 1880. Such a place was called the “operating room” in telephony parlance, creating some amusing connotations.

The first exchange operators were, in the words of John Brooks,

an instant and memorable disaster. The lads, most of them in their late teens, who manned the telephone exchanges were simply too impatient and high-spirited for the job, which, in view of the imperfections of the equipment and inexperience of the subscribers, demanded above all patience and calm. They were given to lightening the tedium of their work by roughhousing, shouting constantly at each other, and swearing frequently at the customers.

Southwestern Bell historian David G. Park shares a typical anecdote:

In Little Rock, [Arkansas,] a prominent saloon keeper rang up and told one of the boy operators, fifteen-year-old Ashley Peay, “Connect me with my telephone at home. I want to talk to my wife.”

Ashley replied, “Your wife is talking to someone else.”

“What do you mean, my wife is talking to someone else?” the saloon keeper growled.

“I mean your line is busy,” Ashley snapped.

The saloon keeper wasn’t accustomed to being turned down by fifteen-year-old boys. “Get my wife on the line right now!” he shouted.

Young Peay’s reaction was to say, “Aw, shut up,” or words to that effect, and yank the connection.

The boy went on to handle other calls. Suddenly he was seized from behind, lifted from the floor, and shaken up and down by a furious saloon keeper. Just as the man was about to fling Peay through a glass window onto the street below, a man in the office came to the operator’s rescue.

Incidents like these occurred throughout the country…

But soon the telephone exchanges hit upon a solution: they replaced the boys with girls, who were not only more demure but willing to work for even lower wages. A newspaper article listed the job requirements:

The physical requirements of girls who are given positions in the telephone exchange are almost as stringent as those insisted upon in men enlisting in the army. To become a “hello” girl, the applicant must be not more than 30 years old [and] not less than five feet six inches tall. Her sight must be good, her hearing excellent, her voice soft, her perception quick, and her temper agile.

Every girl’s sight and hearing is tested and her height is measured before she is hired. Tall, slim girls with long arms are preferred for work on the switchboards. Fat, short girls occupy too much room and are not able to reach all of the six feet of space allocated to each operator.

With regard to nationality, it is said that girls of Irish parentage make the best operators.

The Little Rock, Arkansas, telephone exchange circa 1920, long after the unruly boys had been replaced with girls.

Almost from the very beginning, then, the job of telephone operator was seen as a female occupation, joining the jobs of schoolteacher and nanny in the eyes of the broader culture as another transitory way station for women between the onset of adulthood and marriage. The standard pay of between $1.00 and $1.50 per day reflected this. Those numbers would go up with inflation, but the other parameters of the job would remain the same for well over a century, for as long as it existed. Meanwhile the realization that female voices tend to be less threatening and more soothing in the ears of both genders would become even more embedded in the culture. (When was the last time a computer, smartphone, or GPS gadget spoke to you in a male voice?)

The systems and processes that drove the telephone exchanges improved steadily after 1878, even as the core model of a subscriber asking an operator to manually route his call via a patch wire and a switchboard remained in place for a surprisingly long time. The first telephone numbers made an appearance already in 1879, and quickly became commonplace, what with the way they eased the burden on the operators’ memory and provided telephony’s customers with at least an impression of anonymity. In December of 1887, the first Switchboard Conference was held in New York City. Tellingly, it devoted as much time to social engineering as it did to the technical side of telephony. Many a hand was wringed over the tendency of operators to say, “They won’t answer,” rather than “they don’t answer” in the case of a call that wasn’t picked up, what with the former’s intimation of neglectful intent. And it was agreed that operators should employ short rather than long rings when placing a call because “a short ring excites the curiosity of the subscriber.”

It wasn’t that no one was interested in an automated alternative to manual exchanges. The latter were inherently inefficient; a rule of thumb said that one operator was required during peak hours for every 100 telephone subscribers on a network, constituting an enormous financial drain on service providers even given the minimal salaries they paid to these employees. Despite this ample incentive, the problem kept engineers stymied for years. It was first partially solved by, of all people, an undertaker living in Kansas City, Missouri. Coming along in the last decade of the nineteenth century, Almon B. Strowger was one of the last of the breed of maverick independent inventors cum entrepreneurs who had built the telegraphy and telephony industries in earlier decades, who were soon to give way once and for all to the corporate institutionalists.

That said, Strowger conformed to no one’s stereotype of the genius inventor. Already 50 years old at the time of his achievement, he was a crotchety character whose irascibility verged on paranoia. The stage was set for his stroke of genius when he became convinced that the operators at his local telephone exchange had it in for him, and were deliberately misrouting his calls or not even bothering to place them. (If the anecdotes about his personality are anything to go by, there was perhaps another reason that so few people wanted to talk to him…) One of the operators was the wife of his principal rival in the undertaking business; he believed she was routing his potential customers’ calls to her husband’s establishment instead of his own.

So, he set out to remove the human operator from the equation altogether. His pique and grievance became the impetus behind the first workable automated switching system in the field of telephony.

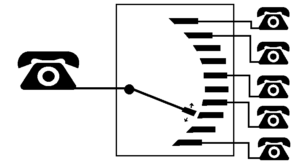

Imagine a telephone whose cable terminates in a rotating electro-mechanical switch or relay, which looks rather like a windshield wiper. There is a button on the telephone. Every time the user presses it, a pulse of current goes down the line which causes the wiper to rotate one step, making a connection with a different receiving telephone. When the user has pressed the button a number of times corresponding to the “phone number” of the person she wishes to call, she presses a second button to cause that phone to ring, and proceeds to have a conversation. When she sets her phone down again, a switch is triggered that resets the system, dropping the wiper back to its home position in preparation for the next call. This is the Strowger system in its most basic form. Routing is still based on changing the physical connections between wires, but those physical changes are themselves now driven by electricity. For this reason, we call it an “electro-mechanical” design.

A network of more than ten or so nodes would be irredeemably tedious for the end-user of such a system, what with all the button-pressing it would require. But, crucially, the system could also be expanded by wiring more relays into it, and adding more buttons to the individual phones to control them. The system which Strowger first publicly demonstrated, for example, used two relay/button combinations to accommodate up to 100 phones, each with a unique two-digit number; the user tapped out the tens digit on one button, the ones digit on the other. In principle, the system could be extended to infinity by wiring yet more relays and buttons into the circuit.

Strowger was awarded a patent for his invention on March 10, 1891, and formed his own company soon after to exploit it. The first fully automated telephone exchange opened in La Porte, Indiana, on November 3, 1892. It was billed as the “girl-less, cuss-less, and wait-less telephone.” Strowger’s company would continue in the exchange business until 1983, first under the name of the Strowger Automatic Telephone Exchange Company and then as simply Automatic Electric.

But automated telephone exchanges would remain the exception to the rule for a long time after 1892; most people understandably preferred speaking a number to a fellow human being over pecking out long strings of digits manually and hoping for the best. Not until the 1920s would automated exchanges come to outnumber the manual ones, relegating the job of telephone operator to that of an occasional provider of information or extra help rather than the essential conduit of every single call. The key breakthrough that finally led to automated telephony’s widespread acceptance was the replacement of Strowger’s push buttons with spring-loaded dials; such “rotary phones” would remain the standard for decades to come, and would continue to function into the 1980s and beyond.

Rotary telephones like this one replaced buttons with a spring-loaded dial that sent the necessary bursts of electricity to move the switching relays at the exchange as it spun back to its resting position.

In the meantime, telephony made do with the manual exchanges. All of their inefficiencies and infelicities were thoroughly outweighed by the magic of the telephone itself. By the turn of the century, 1.4 million telephones were in service in the United States, and 25,000 or more girls and women were employed as operators. The impact of the telephone was different in nature from that of the telegraph, but no less socially significant. While it perhaps didn’t have the same immediate transformative effect on big business and international diplomacy, it was a vastly more democratic instrument, making a far more tangible change in the lives of its millions of individual users. The telegraph was a service, and thus to a large extent an abstraction; the telephone was a personally empowering technology, one you could literally hold in your hand.

Like the smartphones and tablets of our own day, telephones were condemned by certain segments of the intelligentsia, for destroying the old art of letter writing and for being a nuisance and a distraction from the truly important things in life; one article called them “an unmitigated domestic curse,” only good for “the exchange of twaddle between foolish women.” In another uncanny harbinger of more recent history, local newspapers fretted that telephones would slake the public’s thirst for their articles, columns, and calendars. (Unlike our more recent history, such fears would prove largely unfounded in this case.)

But the people couldn’t get enough of the telephone. American Bell — as Bell Telephone was now known, having adopted the new name in 1880 — was rather surprised to discover that the allegedly backward, rural areas of the country actually took to the telephone more readily than many of the nation’s urban centers. Farmers and particularly farmers’ wives, some of whom had heretofore been accustomed to going months at a time without talking to anyone outside their household, jumped on the telephone like a Titanic survivor on a lifeboat. The rural exchanges fostered a welcome new sense of community, becoming deeply embedded in the lives of the people they served, spreading news and gossip to all and sundry. Before Siri and “Hey, Google!,” there was the friendly local telephone operator to play the role of personal assistant, as captured in one housewife’s dialog from a gently satirical magazine article: “Oh, Central! Ring me up in fifteen minutes, so I don’t forget to take the bread out of the oven.” “Central, ring me up half an hour before the 2:17 train in the morning. See if it’s late before you call, please..”

For all the social changes it wrought, telephony extended its range much more slowly than telegraphy had. Cyrus Field’s transatlantic telegraph line had come to be just 22 years after the first telegraph line of any stripe was placed in service. The first transatlantic phone call, by contrast, didn’t take place until January 7, 1927, almost precisely 50 years after Roswell C. Downer had become the first person to have a telephone installed in his home. The delay was down to the nature of the two technologies.

The electrification of the Western world was in full swing at the turn of the century, to telephony’s immense benefit: hand-cranked magnetos and discrete batteries disappeared as companies like American Bell began to flood their networks with current from the grid. But the complex waveforms of telephony required much more power than a telegraph signal to travel an equivalent distance, due to a phenomenon known as attenuation: the tendency of a waveform to shed its peaks and valleys of amplitude and collapse toward uniformity as it travels farther and farther. Attenuation is in fact the same phenomenon in the broad strokes as the “signal retardation” which dogged the early days of undersea telegraphy, but it was never really an issue in terrestrial telegraphy, what with its staccato on-off approach to signaling. It could, however, play havoc with a sound waveform on a wire. The only way anyone knew of to fight attenuation was to add more power to the circuit, which in turn required thicker and thicker cables made of pure copper. This made the telephone into a peculiarly localized technology for instantaneous communication; it could and did foster a new sense of togetherness within communities, but struggled to reach between them. For decades, the American telephone network writ large was actually a bunch of local networks, connected to their peers if at all by just one or two long-distance lines.

Although the market for local telephone service became much more competitive after the expiration of the first of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone patents in 1891, American Bell remained the 800-pound gorilla. The Bell executives had realized even well before that date that long-distance telephony was an area where their superior resources combined with their head start in the telephone business could allow them to sustain their monopoly without leaning on the crutch of patent law. Accordingly, American Bell on February 28, 1885, had formed a new subsidiary to specialize in long-distance telephony, with a name destined to outlive even that of its parent: the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, better known then and now as AT&T.[1]Even at the time of its inception, the name behind the acronym was anomalous if not meaningless, given that AT&T had no holdings in telegraphy; AT&T was content to leave that monopoly to Western Union. The name is perhaps best explained as a warning shot across Western Union’s bows, in case it should ever feel tempted to reenter the telephone market…

The thick, custom-made cables that AT&T employed were expensive to buy and string up, and could only carry one call at a time. These realities were reflected in the prices AT&T charged its subscribers: a ten-minute call over the 292-mile line from Boston to New York City — the longest and most celebrated line on the network at the turn of the century — cost $2 during the day or $1 at night. These were prices that only bankers and investors and other members of the well-heeled set could afford. Long-distance telephony would continue to be their prerogative alone for quite some time to come. Everyone else would have to rely on the telegraph or the even more old-fashioned medium of the hand-written paper missive for their long-distance communications needs. And needless to say, there was little point in thinking about a transatlantic telephone line while the length of even a terrestrial line was limited to 300 miles at the outside.

Rather than crossing the Atlantic, telephony’s overarching goal became to bridge the continent — to string a single telephone cable from the East to the West Coast. In addition to its practical utility, it would be an achievement of immense symbolic significance, a sort of telephonic parallel to the famous driving of the golden spike that had marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

One milestone came courtesy of a Serbian immigrant named Mihajlo Pupin. In 1900, he patented something called a loading coil, which, when placed at intervals along a telephone wire, could greatly reduce if not entirely eliminate a signal’s attenuation by magnetically increasing its inductance, or resistance to change. But there were limits to what loading coils could do. In combination with a very thick cable, they were enough to get a signal from New York City to Denver, but it couldn’t be coaxed any further. What was needed was an equivalent to Samuel Morse’s old telegraphic concept of the repeater: a way of actively boosting a signal as it traveled down a wire. Unfortunately, the simple system of discrete circuits joined by electromagnetic switches which Morse had proposed, and which had indeed become commonplace on telegraph lines by now, was useless for telephony, being unable to preserve the character of an audio waveform.

Then, in 1906, a researcher named Lee De Forest proposed something he called an audion. It was nothing less than the world’s first self-contained audio amplifier, built using vacuum tubes, a technology that would become hugely important outside as well as inside of telephony in the decades to come. The engineers at AT&T realized that it should be possible to install these audions — or simply repeaters, as they would quickly become known — along a terrestrial telephone line to make the voices it carried travel absolutely any distance. The details turned out to be a little bit more complicated than they first appeared, as generally happens in any form of engineering, but AT&T found a way to make it work at last. The company’s marketers came up with the perfect way to mark the occasion.

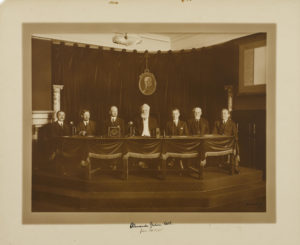

On January 25, 1915, a 67-year-old Alexander Graham Bell, stouter and grayer than once upon a time but still bursting with his old Scottish bonhomie, picked up a telephone before assembled press and public in New York City. “Hoy! Hoy!” he said in his booming brogue. (From the first days of his invention until the end of his own days, Bell loathed the standard telephonic greeting of “Hello.”) “Mr. Watson? Are you there? Do you hear me?”

In front of another assemblage in San Francisco, Bell’s old friend and helper Thomas A. Watson answered him. “Yes, Mr. Bell. I hear you perfectly. Do you hear me well?”

“Yes, your voice is perfectly distinct,” said Bell. “It is as clear as if you were in New York.”

Inevitably, Bell was soon cajoled into repeating those famous first words ever spoken into a working telephone: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.” Whereupon Watson noted that, instead of seven seconds, the journey would now take him seven days. It may not have been a transatlantic link quite yet, but it did feel like a culmination of sorts.

Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson weren’t the only ones on the line that memorable day. Theodore N. Vail, the erstwhile mastermind of Bell Telephone’s successful legal campaign against Western Union, had returned after a lengthy hiatus to serve as president of the company once again in 1907. He listened in to the historic conversation from a telephone on Jekyll Island, Georgia, where he was convalescing from the heart and kidney afflictions that would kill him in 1920.

But before his death, Vail established a new research-and-development division unlike any seen before in corporate America, a place designed to bring the best engineers in the country together and give them carte blanche to solve problems that the world might not even know it had yet. It would become known as Bell Labs, at first informally and then officially, and it would do much to shape the course of not just communications but the entirety of technology — not least the field of computing — over the balance of the twentieth century.

On its home turf of telephony, Bell Labs steadily improved the state of the art of automated switching and developed techniques for multiplexing, so that calls could be routed together along trunk lines instead of always requiring a wire of their own. And it devised ways to integrate Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi’s technology of wireless radio with the network, in order to bridge gaps where wired telephony simply wouldn’t serve. Because no one had yet found a way of installing repeaters on an undersea cable, a transatlantic connection would have to depend on these new techniques of “radiotelephony.”

The call of January 7, 1927, was a curiously muted affair in contrast to the completion of the first transatlantic telegraph cable or even the first transcontinental phone call, involving no greater luminaries than Walter S. Giffords, Vail’s successor as president of American Bell and AT&T, and Evelyn P. Murray, the head of the British mail service, which held a government-granted monopoly over telephony in that country. Nevertheless, it was a landmark moment; while Alexander Graham Bell’s dream of easy, casual conversation across an ocean was still decades away from fulfillment, a conversation was at least possible now, four and a half years after his death. Wireless links such as the one which facilitated this conversation would remain a vital part of the telephone networks of the future, whether in the form of conventional radio waves, microwave beams, or satellite feeds. “Distance doesn’t mean anything anymore,” said one of the engineers behind the first transatlantic call. “We are on the verge of a very high-speed world.” Truer words were never spoken.

Outside of telephony, the Bell Labs boffins created the first motion-picture projector with audio as well as video, and saw it used it in 1927’s The Jazz Singer, that harbinger of a new era of cinema. That same year — a banner one in its history — Bell Labs conducted the first American demonstration of television, starring Secretary of Commerce (and future President) Herbert Hoover. Two years later, it broadcast television for the first time in color. AT&T and American Bell may very well have extended their telephone empire to television in the next decade, had the Great Depression not intervened to put the damper on the consumer economy.

As it was, the fallout from the stock-market crash of late 1929 slowed the march of technology, but could hardly turn back the hands of time. By that point there were more than 15 million telephones in service under the auspices of American Bell alone. Their numbers dropped for a while in the aftermath of the crash, but relatively modestly. By 1937, there were more telephones than ever in the United States and, indeed, around the world.

A review of the literature surrounding the telephone during the decade provides yet more evidence that the concerns surrounding the trendy communications mediums of our own age are not as unique as we might like to think. It seems that worries about communications technologies leading to a dumbing-down of the populace and egotism running rampant did not begin with Facebook and Instagram. A sociological study of 1000 telephone conversations, for example, revealed with horror that only 2240 separate words were used in the course of all of them, which amounted to no more than 10 percent of the words heretofore considered fairly commonplace in English. Worse, the most frequently used words of all were “I” and “me.”

On a more positive note, the telephone was promoted — perchance a bit excessively — as the Great Leveler which would allow the proverbial little people to communicate directly with the movers and shakers of the world, just as Twitter and its ilk sometimes are today. An Ohioan with the delightfully folksy name of Abe Pickens took this lesson to heart, attempting to call up Francisco Franco, Benito Mussolini, Neville Chamberlain, Emperor Hirohito, and Adolf Hitler among others to give them a piece of his mind. He reportedly did manage to get himself connected directly to Hitler at one point, but Pickens spoke no German and Hitler spoke no English; the baffled Führer quickly fobbed his interlocutor off on an aide. Sadly, Pickens did not succeed in preventing World War II.

Even by this late date, the telephone had not yet annihilated its more static predecessor the telegraph. Western Union’s tacit bargain with Bell Telephone of 1878 — you take telephony, we’ll take telegraphy — could still be construed as a wise move on the part of both, in that both companies were still hugely powerful and hugely profitable. The field of journalism remained completely in thrall to telegraphy, as did large swaths of government and business. During the war to come, telegraphy would provide a precious lifeline to loved ones back home for countless soldiers serving in faraway places where telephones couldn’t reach. Still, the telegraph had now become a legacy technology, destined only for stagnation and gradual decline. The future lay in telephony.

This sprawling amalgamation of transmitters, receivers, lines, switches, and gates was one of the wonders of its world — so wondrous that it can still inspire awe when we step back to really think about it today. You could pick up a phone at any arbitrary location and, by dialing some numbers and perhaps talking with an operator or two, make a connection with any arbitrary other phone elsewhere in your country — or in many cases elsewhere on your continent or even planet. And then you could chat with the person who answered that other phone as if the two of you were sitting together in the same parlor. If you ask me, this is amazing — still amazing.

The technological web which allowed such interconnections was arguably the most complex thing yet created by human ingenuity — so complex that no one fully understood all of its nooks and crannies. The fact that it actually worked was flabbergasting, the fact that it did so less than a century after Samuel Morse had first figured out how to send single bursts of electronic current down a single wire nothing short of mind-blowing. When we look at it today, when we think about its bustling dynamism, its little packets of conversation and meaning flying to and fro, it’s easy to see it as a sort of massive cyber-organic computer, doing the work of the world. If most contemporary people weren’t discussing the telephone network in those terms, it was because half of the analogy literally didn’t yet exist for them: the concept of an “anything machine” in the form of a programmable computer, while by no means a new one in some academic and intellectual circles, was still a foreign one to the general public.

But it wasn’t foreign to a young man named Claude Shannon.

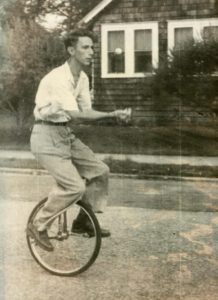

Anything but a stuffy academic, Claude Shannon was one of the archetypes of the playful hacker spirit which would fully emerge at MIT during the postwar years. “When researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or Bell Laboratories had to leap aside to let a unicycle pass,” writes James Gleick in The Information, “that was Claude Shannon.”

Shannon had grown up on a farm in rural Michigan, tinkering with homemade telegraphs that repurposed barbed-wire fences for communication. After taking a bachelor degree in electrical engineering and mathematics from the University of Michigan, he came to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a 20-year-old prodigy in 1936, having been personally recruited by Dean of Engineering Vannevar Bush to work on the Differential Analyzer, a 100-ton semi-programmable analog calculating machine designed to relieve the grunt work of solving complex mathematical problems. Inside Shannon’s fecund mind, the Differential Analyzer collided with his abiding interest in telegraphy and telephony and his memories of a class he had taken in Michigan on symbolic logic, and out popped “A Symbolic Analysis of Relays and Switching Circuits,” a paper which has been called “the most important master’s thesis of the twentieth century.”

Within his thesis, Shannon presented a plan for an electro-mechanical computer built around the digital logic of ones and zeroes — a machine far more flexible than the likes of the Differential Analyzer, yet one that required only the off-the-shelf equipment of telephony rather than the many bespoke wheels and gears of its gargantuan steampunk inspiration. Shannon’s pivotal insight was that switches on a circuit could not only route information but constitute information: an open switch could indicate a one, a closed switch a zero, and everything else could be built up from there. Abstract logic could be rendered concrete in circuitry: “Any operation that can be completely described in a finite number of steps using the words ‘if,’ ‘or,’ ‘and,’ etc., can be done automatically with relays.” I should hasten to clarify that the only way to reprogram one of Shannon’s hypothetical computers was to physically rewire it — effectively to remake it into a brand new machine. And again, it was still at bottom an electro-mechanical rather than a purely electrical device. Still, it was a major milestone on the road to the modern digital computer.

The technologies of telephony would continue to be repurposed to suit the needs of the burgeoning field of computing in the years that followed. The vacuum tubes that served American Bell so well for so long, for example, found a new application at the heart of the first programmable digital computers of the postwar era. And that technology in turn gave way to another one first developed for telephony: the transistor, which was invented at Bell Labs in 1947 and went on to become, as John Brooks wrote in 1976, “the key to modern electronics,” facilitating everything from hearing aids to the Moon landing. The transistor also lay behind the first wave of truly widespread institutional computing, over the two decades prior to the arrival of personal computers on the scene in the late 1970s.

But these developments, important though they are, are not the main reason I’ve chosen to tell the story of the analog technologies of the telegraph and telephone on a site about the history of digital culture. I’ve rather done so because computer engineers did more than borrow from the tool kits of the electrical-communications infrastructure of their day: they also came to borrow the existing communication networks themselves. This was the result of an insight which seems so self-evident as to be almost banal once it has been grasped, but which took the brilliant mind of Claude Shannon to appreciate and articulate for the first time: the fact that an electric current which could carry the dots and dashes of Morse code or the sound of a human voice could be made to carry any kind of information. This simple realization was the key that opened the door to the Internet.

(Sources: the books Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude by Robert V. Bruce, Telephone: The First Hundred Years by John Brooks, Good Connections: A Century of Service by the Men and Women of Southwestern Bell by David G. Park Jr., From Gutenberg to the Internet: A Sourcebook on the History of Information Technology edited by Jeremy M. Norman, The Information by James Gleick, The Dream Machine by M. Mitchell Waldrop, and The Practical Telephone Exchange Handbook by Joseph Poole. Online sources include Bob’s Old Phones by Bob Estreich, “Telephone History” by Tom Farley, “Telephone Switches” by Mark Csele, “The Strowger Telecomms Page” of SEG Communications, and “Today in History: The First Transatlantic Phone Call” by Priscilla Escobedo for UTA Libraries.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Even at the time of its inception, the name behind the acronym was anomalous if not meaningless, given that AT&T had no holdings in telegraphy; AT&T was content to leave that monopoly to Western Union. The name is perhaps best explained as a warning shot across Western Union’s bows, in case it should ever feel tempted to reenter the telephone market… |

|---|