This article contains capsule reviews of ten of the discs that I most appreciate from the early years of The Voyager Company, along with some additional notes on their origins, courtesy of Bob Stein. Before starting in earnest, some explanations are in order:

I’ve always envisioned this history of digital interactivity as something of an interactive experience in its own right for its readers. I’ve always hoped that some percentage of you will be inspired to check out some of the artifacts I write about for yourself, inspired to go on your own journey through digital history and form your own judgments about what you find there. I’ve always done my best to facilitate that.

In the early years, that sometimes meant rolling up my sleeves and getting down in the weeds with the often-cranky emulators of now-obscure old computers, sharing ROM files and the like and even on one occasion packaging up a whole obsolete computer system in a (virtual) box. In the middle years, things got a bit easier, as I could generally just share disk images of the software I wrote about for you to try out on the more mature emulators of slightly later computers. And still more recently things have gotten easier yet, as most of the stuff I write about these days can be purchased as ready-to-run downloads from digital storefronts like GOG.com. (Indeed, the emergence of a permanent back catalog in a games industry that used to make a policy of forgetting its past is one of the most welcome developments I’ve had the pleasure to witness since I started this site.)

But when it comes to exploring the fascinating catalog of The Voyager Company, we’re kind of back to square one. The sad fact is that classic Macintosh emulation is far less mature than that of MS-DOS, early incarnations of Microsoft Windows, or even the Commodore 64 or Amiga. This isn’t, I rush to add, because the people who work on the three most prominent classic Mac emulators — each focusing on a distinct era of the long-lived platform — are any less capable than those working on other emulators, but just because it’s a big job and there aren’t a lot of people doing it in comparison to those endeavoring to preserve the more popular retro-gaming platforms.

The Voyager oeuvre has a particular knack for finding the weaknesses in the current generation of Mac emulators. Many of Voyager’s early releases are what’s known as “mixed-mode” CD-ROMs: CDs which combine a computer-specific “data track” with multiple other tracks of sound and/or music, readable by any audio-CD player. All of the extant emulators tend to choke horribly on these. Even the later Voyager releases, which generally aren’t mixed-mode, are often a tall order for the emulators, having been built using fiddly middleware like HyperCard or The Director, and being loaded to the gills with multimedia content to be played back using equally fiddly libraries like QuickTime. One usually can get them to work in the emulators, after a fashion, but they’re all too often glitchy and crash-prone.

I’m therefore going to recommend a radical solution to anyone interested in experiencing the Voyager discs I highlight below: don’t try to do it on an emulator. Get yourself a real vintage Macintosh instead.

Specifically, I recommend picking up a G3 iMac or iBook of the turn-of-the-millennium era. Apple sold millions and millions of these little machines, and they can still be found all over the place in North America and Europe: on online marketplaces, at swap meets, in charity shops, in your neighbors’ attic — or perhaps in your own. I bought a 1999-vintage iMac here in Denmark — not exactly the cheapest country in the world — for the equivalent of $100 US a year and a half ago. I suspect that most of you can do much better than that if you’re willing to look around a bit.

These models have several other advantages beyond their ubiquity and cheapness. They’re easy to set up and take down, for one thing. And they’re just new enough to sport some very useful modern conveniences, like an Ethernet port and a USB port that can handle thumb drives, both a godsend for transferring files. Most importantly, they will run the entire Voyager product line more or less flawlessly. You just need to be sure you have some incarnation of MacOS 8 or 9 installed — the exact version really doesn’t matter — rather than OS X.

With your trusty iMac or iBook running MacOS 8 or 9 and a stack of blank CDs for burning to hand, there are only a couple of other things you need to know in order to dive into the Voyager catalog. All of the discs I describe below are hosted by The Macintosh Garden, a site which performs an invaluable service but which does have its idiosyncrasies. One of these is the use of the Mac favorite Stuff-It rather than a more universal standard as its compression tool of choice. If you use a modern Mac, you probably already have this software; if not, you’ll need to download it and install it on your everyday computer.

The files you’ll find inside the archives will be either ISO disc images, Toast images, or bin/cue images. The first can be burned to a physical CD-ROM for use on your vintage Mac directly from most modern operating systems. The second can be renamed with the extension “.iso” and burned the same way, if you don’t happen to own a modern Macintosh with Roxio Toast installed. The third is the most complicated, as it generally indicates one of the aforementioned mixed-mode CDs; you’ll need to have or acquire third-party software capable of burning these types of discs.

I must say that I’ve been immensely enjoying the tactility of using real hardware to explore the Voyager catalog. Perhaps you’ll feel the same. But the diehards among you can of course still try your luck with emulators; feel free to describe any information or solutions you discover in the process in the comments below. Note as well that a minority of the Voyager discs were also released in versions for Microsoft Windows, or as dual-platform discs that can run on either Mac or Windows. So, that might be another direction of inquiry for some of you in some cases.

And now on to what I really want to tell you about today…

AmandaStories (1991)

AmandaStories is one of those quietly influential works that can sometimes make my job so interesting. It’s the creation of a woman named Amanda Goodenough, who was the wife of HyperCard creator Bill Atkinson’s marriage counselor circa 1987. When the latter brought home a pre-release version of HyperCard, courtesy of his client, his wife started to use it to chronicle the adventures of her little black cat Inigo in the form of an interactive picture book.

Amanda Goodenough’s personal story — that of a thoroughly non-technical housewife who was able to create something remarkable thanks to the magic of HyperCard — made her a minor celebrity in the Macintosh world, a living symbol of HyperCard’s ethos of egalitarian creative empowerment. Bob Stein and his colleagues from Voyager first met her at the January 1988 Macworld show, where she was demonstrating her latest stories at the same time that they were demonstrating their HyperCard-and-laser-disc-driven exploration of the National Gallery of Art. They soon inked a deal to release her first four stories on floppy disk under the Voyager imprint. A second collection of stories followed a little later, this time starring a good-natured camel known simply as My Faithful Camel. The CD-ROM version featured here adds two more Inigo stories and supplements the silent black-and-white originals with colorized versions featuring occasional sound effects and music swells.

Yet what these AmandaStories led to is ultimately more important in the context of history than what they were. Among the people who admired them in those heady early days of HyperCard was a professional programmer and amateur Macintosh enthusiast named Rand Miller. They became a profound influence on The Manhole, the interactive picture book he created with his brother Robyn Miller; both works employ the same literally transparent interface, where everything happens as a result of clicking directly on the pictures on the screen rather than on buttons, menus, or other widgets. Voyager came very close to publishing The Manhole as well — “It was clear these guys were going somewhere,” says Stein — but was outbid in the end by Mediagenic.

After making a few more children’s titles, the Miller brothers decided to bring the same minimalist approach to an adventure game for adults. The result was 1993’s Myst, which sold at least 6 million boxed copies during the remaining years of the decade and created a whole sub-genre of adventures in its image. “We might have gotten Myst, and the world might have been very different,” muses Stein today of what is perhaps Voyager’s most obvious missed opportunity.

But they did at least get these stories which did so much to inspire Myst, and we can feel fortunate for that. AmandaStories remains as sweet and clever as ever, suitable for children and adults of any age.

I Photograph to Remember (1991)

I Photograph to Remember by the Mexican photographer Pedro Meyer tells the story in pictures of the last three years of his parents’ lives, a period during which both were diagnosed with cancer and died of the disease. It engages with the essentials of human life and death in a way that very few digital works dare to do. Meyer’s photographs of his parents’ decline are not always easy to look at, but the unflinching honesty of the presentation makes it a necessary antidote to the escapist entertainments that usually dominate our monitor screens. Anyone who has been a caregiver or even just a witness to someone approaching the end of all ends will recognize the story that unspools here, so unique to Meyer’s family but also so universal.

Once one looks beyond the sadness at its core, the origin story of I Photograph to Remember turns out to be rather amusing. Bob Stein:

I’m at a party talking to a guy I don’t know, and he’s telling me about this amazing CD-ROM he’s gotten, about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When I tell him that I had a hand in making it, he invites me to his home and he shows me these 90 photographs that he took during this period of his parents’ lives. I realize that what’s he just done in effect is to give me a narrated slideshow, and that, because we can now show a high-resolution photograph on a computer screen with audio, we could publish that. It’s completely different from showing it on a television set, which just doesn’t have the resolution. And Pedro says, “Of course we should publish it on CD-ROM.” In retrospect, having known Pedro for years, I think he knew exactly what he was doing. He knew what was going to come out of that meeting; he’s very sly.

There was no question about which photographs we were going to show. And Pedro has this beautiful voice. All of that was a no-brainer. He hired a young man named Manuel Rocha to write the music. The first version was the most god-awful European synth-pop. I heard Pedro literally screaming at Manuel about this, telling him how terrible it was. I thought to myself, you can’t treat somebody like that; there’s no way that’s going to get the intended result. But he comes back a week or two later with a gorgeous soundtrack: minimalist and perfect. Who knows how you motivate people?

This is 1991. Up until that moment, as far as I know, nobody has used a computer to present deep emotional content. We showed it for the first time at this fancy conference that took place every year in Los Angeles. There were 500 people in the room, probably 95 percent men, all executives in suits. You could have heard a pin drop. People were stunned: “Oh, my God! This is what we can do with a computer?” That was exciting.

If there’s a complaint to be made about I Photograph to Remember today, it must be that the piece is hardly interactive at all, and could work just as well as a short film presented on a high-definition screen; once you’ve chosen whether you wish to hear Meyer’s narration in Spanish or English, it quite literally plays itself. But no matter: while I might quibble with Bob Stein’s claim that no computer-based work prior to this one attempted “to present deep emotional content,” there is no question that this one positively trembles with the ineffable joys and pains of our feeble mortal existences. If you’ve come to Voyager’s catalog looking for Art, you will most definitely find it here.

Last Chance to See (1992)

In the late 1980s, the BBC sent the humorist and novelist Douglas Adams and a zoologist named Mark Carwardine on a series of journeys to remote regions of the world in order to seek out some of our planet’s most unusual and endangered forms of wildlife. The 1989 television series which resulted became a book the following year, and finally this CD-ROM production two years after that. Bob Stein doesn’t think that highly of it, for perfectly coherent reasons: it’s little more than the raw text of the book read aloud by Adams, with occasional embedded sidebars to click on. It is, in other words, more of an ebook than an electronic book of the sort Stein was always trying to create.

Personally, though, I find that its formal limitations do little to diminish its impact. Douglas Adams was a unique mind who left us far too soon and wrote far too little even while he was with us. The Last Chance to See project was particularly welcome for giving him a chance to set aside silly two-headed aliens and towels in space in favor of things that really matter to our world. It’s poignant to hear him read his own words here, knowing that, although he would live for almost nine years after the release of this CD-ROM, he would never complete another book. Listening to his wit and wisdom, dealing not only with the ofttimes bizarre natural world but with the equally bizarre human foibles of the countries the two men visited, one can’t help but lament that fact.

But equally poignant are the fates of some of the strange animals Adams and Carwardine pursue. Few things can better bring home to you what we are losing than the act of listening to this CD-ROM and then looking up the current status of its subjects. The Yangtze river dolphin is probably extinct now; the northern white rhinoceros soon will be, given that the only two specimens that are left are both female. The title of Last Chance to See proved prophetic in those two cases at least, making it all the more precious for us today and those who will follow us as a document of wondrous creatures that used to be.

Poetry in Motion (1992)

Poetry in Motion repurposes footage captured for a 1982 documentary film of the same name, itself a work that occupies a special place in the history of Voyager: it was in fact the company’s very first product, published as a videotape in the short interim between Bob and Aleen Stein’s split with their Criterion Collection co-founder Roger Smith and their subsequent re-acquisition of the Criterion name. Bob Stein believes the film is better than the CD-ROM, but the latter does feature performances and interviews that the former lacks. Whichever format you choose to view it in, it’s a riotously good time, capturing the elder statesmen of the Beat Generation in a dialog of sorts with literary and musical up-and-comers, all set against the backdrop of the New York City and Toronto New Wave and No Wave scenes. Here you can see Allen Ginsberg belting out a spirited if harmonically challenged reading with a punk-rock backing band, and Tom Waits captured just as he is making the transition from his 1970s boozy-troubadour persona to the raucous cacophony of his 1980s records.

The Achilles heel of the CD-ROM Poetry in Motion, the primary source of Bob Stein’s dislike for it, is the usual one for Voyager products of this ilk: poor video quality. The film footage is a grainy postage stamp, so much so that it’s often difficult to determine exactly what it is you’re actually looking at. And yet the performances themselves are so bracing that they manage to carry you away anyway. Poetry in Motion is an indispensable snapshot of an instant in literary and musical history.

A Hard Day’s Night (1993)

The CD-ROM version of the classic 1964 Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night was Voyager’s most successful single product after the CD Companion to Beethoven, selling 100,000 copies in all — i.e., at least an order of magnitude more than the typical Voyager disc. And indeed, I can remember seeing it in software stores regularly during the mid-1990s, a memory I don’t have of any other Voyager product. This disc’s lodging in my brain may have something to do with my personal predilections; I’ve been a rabid Beatles fan ever since my cool big sister introduced them to me while my age was still in the single digits. But I do think that it also reflects the unusual reach of this particular Voyager CD-ROM, which was widely reviewed in such mainstream-media bastions as Entertainment Weekly magazine.

I won’t say too much about the film itself here, other than to note that it’s brilliant, the sights and sounds and excitement of a cultural revolution — thankfully not the kind advocated by Chairman Mao! — distilled into 87 potent minutes. More relevant for our purposes is Voyager’s approach to adapting the movie to this new medium of CD-ROM — if, that is, “adaptation” is even the right word. This is far from the ideal way to view A Hard Day’s Night for pleasure, whether for the first or hundredth time, given the absolutely awful video quality. But by way of compensation, it’s an innovative new way of studying the film. “Nobody was going to take this seriously as film,” Bob Stein says of the Voyager disc, “but we could do something fun with it.”

At first glance, the CD-ROM of A Hard Day’s Night might seem to have much in common with the laser-disc version of the film which Criterion had released earlier: the movie accompanied by a host of extras meant to deepen one’s understanding of it and to lend it context. Look closer, however, and differences quickly emerge. The CD-ROM’s approach is fundamentally textual, making it closer to an electronic book than the notion of a film on CD-ROM might initially imply: its core features are an extended essay by the respected Australian pop-culture journalist Bruce Elder and a complete copy of the shooting script. The latter is especially interesting, offering up the unique opportunity to watch the film in a window as one follows along in the script.

So, rather than being an early, technologically unsatisfactory example of what DVDs would later become, as one might be tempted to assume, the Voyager A Hard Day’s Night is in fact an example of a road not taken in film studies. DVDs and Blu-ray discs are able to combine what Voyager does here with superb video quality, and yet this capability has gone almost entirely unexplored. “To this day, it drives me crazy that Criterion has never tried to merge what we did with A Hard Day’s Night into their usual approach,” says Bob Stein. “Given that all the Criterion stuff is digital at this point, why can’t they associate the script of a movie with the movie itself?” Chalk it up as just one more symptom of our increasingly post-textual culture.

Who Built America? (1993)

Who Built America? is a CD-ROM adaption of a paper book of the same name by Roy Rosenzweig and Steve Brier: a history of the United States from 1876 to 1914. Bob Stein explains how one of Voyager’s most earnest attempts to realize the ideal of the electronic book came to be:

I was browsing the history section of the Harvard bookstore one day and this book popped out at me. It was from Knopf, so I figured it was somewhat credible, and the authors had a point of view which I liked. So, I got on the train to New York the next day and found the authors at Hunter College. I showed them the Beethoven CD-ROM, and said, “Let’s do something together.” They were techie kinds of guys; they were excited about it. We spent a year just talking, trying to figure out what the sweet spots were and what we could add to the equation by making their book electronic.

The breakthrough came for me when I realized that all history books are syntheses of the authors’ readings of documents, conversations they have, etc. Wouldn’t it be interesting to publish a history book including not just the synthesis that the book itself represents, but also with the documents that the synthesis was based on? In effect, let the readers participate as historians, reading the documents for themselves. That’s how we came up with these things we called “excursions”: at most points in the book, you can click on a link and see the original associated documents.

It’s not hard to grasp why Stein would find this particular history book so compelling, what with his own background as an activist for the workers of the world. Both its authored text and the many primary sources that branch off of it emphasize, almost to the exclusion of all else, the experiences of those marginalized and less empowered souls who do not tend to garner much attention in traditional narrative histories: immigrants, ex-slaves, racial and ethnic minorities, the working poor, etc. This determination to focus on the stories that are not usually told prevents the book from being a truly complete chronicle of Gilded Age America; the assassinations of two separate presidents are only a couple of the earthshaking events that it barely even bothers to mention.

And yet, if you go into it understanding the limitations imposed by the authors’ philosophy and perhaps ideology of history, you may just find what is present here extraordinarily compelling. I read literally every word over the course of many evenings, clicking on every link to read the primary-source documents, to view photographs and newspaper cartoons, to watch film clips and listen to songs, interviews, and other audio snippets. So very much of what you find in these excursions is, dare I say it, heartrending. A priceless cache of letters from Polish immigrants to the United States, writing to family members back in the Old World whom they will almost certainly never see in person again, is just one example. Who Built America? is a deeply empathetic social history of a fraught era whose legacy is still an inescapable reality of modern American life.

Baseball’s Greatest Hits (1994)

Voyager’s one foray into the world of sports was prompted to a large extent by the rediscovery of an artifact that’s sometimes been called “baseball’s Zapruder film”: a piece of 16mm footage shot by a fan during the 1932 World Series. It shows Babe Ruth hitting what is arguably the most famous home run in baseball history: his “called shot” home run, which receives its name from the tale that he pointed to exactly what corner of the park he planned to hit it to before taking the pitch. While the film is ultimately inconclusive — it appears to show Ruth making some sort of gesture, but it’s impossible to say more than that — it’s tremendous fun to watch it and to speculate about what one might be seeing.

But Baseball’s Greatest Hits has much more than one film clip to offer. It serves as a fine example of what made Voyager different from most of the others rushing to put content onto CD-ROM during the 1990s. Baseball fans’ love of statistics is famous; this made the sport a natural subject for any number of unimaginative encyclopedic CD-ROM data dumps from companies such as Microsoft.

Baseball’s Greatest Hits, on the other hand, is something else entirely. Rather than focusing on the numbers, it’s interested in the legends and lore of America’s Pastime, making it as legitimate a form of social history as the likes of Who Built America?. The heart of this curated collection is a timeline of “Great Moments,” stretching from the 1932 called-shot game to the 1993 World Series. Each great moment is introduced by the unmistakable voice of Mel Allen, the longstanding announcer for the New York Yankees, who died just a few years after this disc appeared. The great moment then goes on to feature radio and/or television clips from the day in question, excerpts from newspaper accounts, and score cards and the like for the stats-heads. The end result is not only a wonderful celebration of baseball, that most lore-rich of all American sports, but also a window into the 60 years of American history that’s reflected by these fields of dreams. Bob Stein:

It’s a fantastic disc. I’m not a huge baseball fan, but I loved that disc. How come there’s nothing that good now on the Internet, 25 years later? It’s one of the things we did that you look at and wonder… it was great then, how come nobody’s done it since?

I don’t know, Bob. I can say only that Baseball’s Greatest Hits is one of my favorites too of all the Voyager discs, and one I’d encourage everyone to try, baseball fan or no.

People: 20 Years of Pop Culture (1994)

“We wanted to experiment with something that you could theoretically sell at a supermarket check-out,” says Bob Stein of what appears at first glance to be the cheesiest disc Voyager ever published. “I wasn’t embarrassed that we did it, but I wasn’t particularly proud of it.” Certainly no one would ever accuse People magazine of being any bastion of hard-hitting journalism, nor of reflecting anything but the most conventional of mainstream conventional wisdom.

And yet this archive of the magazine’s cover stories between 1974 and 1994 is by turns nostalgic, funny, surprising, and informative when revisited today. The magazine’s very ethos of hewing so firmly to the middle of the road in all matters makes it a telling barometer of which way the cultural winds were blowing on any given week. Often this archive serves to illustrate how much the world has changed, as when it treats the virulent white suprematism and segregationism of the former Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace as little more than a minor personal foible. For people of a certain age like your humble writer here, it’s constantly bringing on a burst of remembrance, of some actor or television show from your childhood that you haven’t thought of in ages. Flipping through the pages reveals a cornucopia of the petty scandals that once kept people talking in those supermarket-checkout lines — Gary Hart and Donna Rice, Vanessa Williams — and the equally inescapable, “heart-warming” human-interest stories of the moment — the boy in the bubble, the girl down the well — all chronicled in delightfully awful purple prose. From time to time amidst it all, the magazine manages to transcend itself, as in a 1987 piece on the tragedy of the AIDS epidemic, describing the lives and deaths of some of the disease’s victims with compassion and a notable lack of judgment. (Of course, that same lack could be taken as an indicator of American society’s glacially shifting attitudes toward homosexuality in general. Again, People magazine is nothing if not a faultless barometer of the mainstream.)

This disc may be the closest thing to a guilty pleasure in Voyager’s catalog. If so, I plead guilty as charged: I love it unashamedly.

Ephemeral Films: 1931 to 1960 (1994)

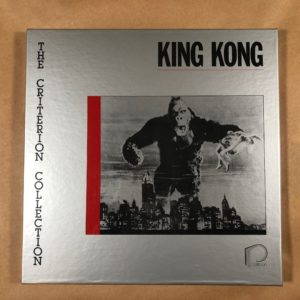

Ephemeral Films collects 38 pieces of celluloid flotsam and jetsam, the sort of movies that will most definitely never be considered for the Criterion Collection: promotional films, corporate training films, educational films for the classroom, etc. They come from the collection of Rick Prelinger, a tireless archiver of pop-culture ephemera who was toiling in obscurity when Bob Stein first met him. “When I saw what he was doing,” says Stein, “which was basically dumpster diving outside some of the most important producers of educational and inspirational films, I started calling him a media archaeologist. I convinced him to work with me to publish some of the films. We chose them and edited them so they would be more compact and interesting.” Prelinger would go on to an important career, working with organizations like the Internet Archive and his and his wife’s own Prelinger Library.

The highlights (lowlights?) here are legion: an Oldsmobile advertisement from 1931 that’s stuffed from top to bottom with sexual innuendo; the 1940 film where a creepy male doctor teaches women how to “relax”; the 1946 promo reel pushing mass-produced homes made out of steel of all building materials on the country’s returning GIs; the 1956 celebration of consumerism known as “Two-Ford Freedom,” which promises that housewives never again will need to feel like “prisoners in their own homes.” (It seems the 1950s were not big on public transport, cycling, or even walking…)

But my personal favorite is the timeless classic A Date with Your Family, a stultifying “social-guidance film” made for the classrooms of 1950. “The women of this family feel that they owe it to the men of the family to look relaxed, rested, and attractive at dinnertime,” says the narrator approvingly; tellingly, the sons have spent their time before dinner doing homework while the daughter spent hers with her mother in the kitchen. “The boys greet their dad as though they were genuinely glad to see him, as though they really missed him and are eager to talk to him,” the narrator continues without a trace of irony. “Pleasant, unemotional conversation helps digestion,” we learn. “Let Father and Mother guide the conversational trend. After all, they made all this possible.”

Films like these are as hilarious as they are horrifying; The Stepford Wives has nothing on them. Taken as a whole, Ephemeral Films explains in the course of an evening or two why the country needed Elvis Presley and the Beatles.

The Complete Maus (1994)

Maus by Art Spiegelman is a landmark in the history of the comic as an art form, being the first graphic novel to be taken seriously by the literary establishment. It’s based upon many hours of interviews which Spiegelman conducted with his father, a survivor of Auschwitz who immigrated to the United States from his native Poland after the war. In translating his father’s harrowing stories to the comics medium, Spiegelman turned the Jews into mice — thus the title, which is German for “mouse” — and the Nazis into cats. It took him some twenty years in all to complete the work, which was published in its final form in 1991, long after the death of the man whose travails it chronicled. Bob Stein:

The Museum of Modern Art in New York did an exhibit on Maus. I went to see it. It had a lot of audio of his father and sketches. I said, “This should be a CD-ROM.” Then one day out of the blue we got a phone call from Art’s agent, saying, “Art wants to make a CD-ROM out of Maus.” Obviously, we said yes.

But it turned out that Art did not give a flying fuck about CD-ROM. He wanted somebody who was stupid enough to take on the task of digitizing the 20,000 sketches he had made when he was creating Maus. That was what he wanted, to preserve the sketches. We did that, of course, in return for the right to make the Maus CD-ROM.

The CD-ROM contains the graphic novel in its entirety, supplemented by many of those concept sketches, by film clips and photographs of the places mentioned in the novel, by interviews with Art Spiegelman, and, most intriguingly of all in my opinion, by some of the recordings he made of his father telling the stories that later became the comic. I’ve heard it said that this is not the ideal way to read Maus for the first time, that the work was designed for the paper page and is best experienced there. That may very well be, but this CD-ROM was my own first encounter with it, and I found it a very affecting experience indeed. Real aficionados of comics — I’m afraid I’m not one of these; my wife is the reader of graphic novels in our family — will doubtless find deeper layers of interest than I did, what with all of the insight on process to be discovered here. One might go so far as to say that this CD-ROM is what the Criterion Collection might have been if it had focused on books rather than movies.