We made it simple yet complex enough for those people who really got into it. We added graphics and made it a beautiful game with a totally transparent interface. It took all the ugly stuff out of playing a military strategy game and left the fun and the gameplay. That was a conscious effort. It wasn’t just, “Gee, I like artwork in wargames, so let’s throw it in.”

— SSI marketing manager Karen Conroe, speaking about Panzer General in 1996

When we last checked in with Joel Billings and his crew of grognards turned CRPG mavens at SSI, it was early 1994 and they had just lost their Dungeons & Dragons license, by far their biggest source of revenue over the past seven years. While Billings continued to beat the bushes for the buyer that his company plainly needed if it was to have any hope of surviving in the changed gaming landscape of the mid-1990s, it wasn’t immediately obvious to the rest of the in-house staff just what they should be doing now. Ever since signing the Dungeons & Dragons deal with TSR back in 1987, virtually all they had worked on were games under that license; SSI’s other games had all come from outside studios. But now here they were, with no Dungeons & Dragons, no clear direction forward, and quite possibly no long-term future at all. Instead of devoting their time to polishing up their résumés, as most people in their situation would have done, they plunged into a passion project the likes of which they hadn’t been able to permit themselves for many years. And lo and behold, the end result would prove to be the game that turned their commercial fortunes around, for a while anyway.

The project began with Paul Murray, an SSI stalwart who had first begun to program games for the company back in 1981. Most recently, he had been assigned to port Dark Sun: Shattered Lands, SSI’s ambitious and expensive attempt to prove to TSR that they deserved to retain the Dungeons & Dragons license, to the Super Nintendo console. But cash-flow problems during 1993 had forced Billings to shelve the port, leaving Murray without much to do. So, he started to tinker with a style of game which SSI hadn’t done in-house in nearly a decade: a traditional hex-based wargame, based on World War II in Europe. From the beginning, he envisioned it as a “lite” game, emphasizing fun at least as much as historical accuracy — i.e., what old-timers called a “beer and pretzels” wargame. In much of this, he was inspired by a Japanese game for the Sega Genesis console called Advanced Daisenryaku, which had never been officially imported to the United States or even translated into English, but which he and his office mates had somehow stumbled upon and immediately found so addicting that they were willing to struggle their way through it in Japanese. (When Alan Emrich from Computer Gaming World magazine visited the SSI offices, he saw them all playing it “with a crude translation of the Japanese manual lying beside the Sega Genesis.”)

After Dark Sun was released to disappointing sales, thus sounding the death knell for the Dungeons & Dragons license, Murray continued to poke away at his “fast and fun little wargame,” which he called Panzer General. And a remarkable thing happened: more and more of his colleagues, both those in technical and creative roles and those ostensibly far removed from them, coalesced around him. Even Joel Billings and his right-hand man Chuck Kroegel, who between them made all of the big decisions in the executive suites, rolled up their sleeves and made their first active contributions to the nuts and bolts of an SSI game in years. They did so largely after hours, as did many of the others who worked on Panzer General. It became a shared labor of love, a refuge from those harsh external realities that seemed destined to crush SSI under their weight.

At this point, a music fan like me finds it hard to resist comparisons with some of great dead-ender albums in the history of that art form, like Big Star’s Third. If SSI’s beer-and-pretzels wargame doesn’t have quite the same heft as an artistic statement like that one, it is true that the staff there felt the same freedom to experiment, to make exactly the game they wanted to make, all born from the same sense that there was nothing really left to lose. Desperation can be oddly freeing in that respect. Billings still speaks of Panzer General as the most satisfying single project he’s ever been involved with. After the extended detour into Dungeons & Dragons, he and his like-minded colleagues got to go back to the type of game that they personally loved most. It felt like going home. If this was to be the end of SSI, how poetically apt to bring things full circle before the curtain fell.

But make no mistake: Panzer General was not to look or sound like the ugly, fussy SSI wargames of yore. It was very much envisioned as a product of the 1990s, bringing all of the latest technology to bear on the hoary old wargame genre in a way that no one had yet attempted. It would be the first SSI game to require high-resolution SVGA graphics cards, the first to incorporate real-world video clips and voice acting, the first to take full advantage of the capabilities of CD-ROM. Luckily, the nature of the game lent itself to doing much of this on the cheap. Instead of filming actors, SSI could simply digitize public-domain newsreel footage of World War II battle scenes. Meanwhile the voice acting could be limited to a single Reichsmarschall giving you your orders in the sort of clipped, German-accented English that anyone who has ever seen a 1950s Hollywood war movie will feel right at home with. Thanks to the re-purposed media and plenty of free labor from SSI staffers, Panzer General wound up costing less than $400,000 to make — barely a third the cost of Dark Sun.

In addition to all of its multimedia flash, Panzer General evinced a lot of clever design. During 1994, strategy-game designers seemed to discover all at once the value of personalizing their players’ experiences, by giving them more embodied roles to play and by introducing elements of story and CRPG-style character progression. X-COM and Master of Magic are the first two obvious examples of these new approaches from that year, while Panzer General provides the third. One can only assume that SSI learned something from all those Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs.

The overall structure of Panzer General draws heavily from Advanced Daisenryaku. It’s a scenario-based rather than a grand-strategy game. If you choose to play the full campaign, you begin on September 1, 1939, leading the Wehrmacht into Poland. You then progress through a campaign which includes 38 potential scenarios in all, covering the Western and Eastern Fronts of the war in Europe as well as the battles in North Africa, but you’ll never see all of them on a single play-through. Panzer General rather uses a Wing Commander– style campaign tree: doing poorly will lead you to the “loser scenario,” and can eventually get you drummed out of the military entirely; doing well leads you to the next stage of world domination, with additional rewards in the form of “prestige points” which you can spend to improve your army. There’s an inherent design tension in such an approach, which I discussed at some length already in the context of Wing Commander: it gives beginning or unskilled players an unhappy experience by punishing them with ever more brutally difficult missions, even as it “rewards” the players who might actually have a chance of beating those missions by bypassing them. Within its chosen framework, however, Panzer General‘s campaign is very well-executed, with plenty of alternative outcomes on offer. In the absolute best case — in game terms, that is — you can invade and defeat Britain in 1940, as Adolf Hitler so conspicuously failed to do in real life, then go on to take Moscow, and finally attain the ultimate Panzer General achievement: conquering Washington, D.C.

As that last unlikely battle in particular would suggest, Panzer General‘s fidelity to real history is limited at best. You don’t have to look too far to find veteran grognards complaining about all the places where it falls short as a simulation, perhaps most notably in its near-complete disinterest in the vagaries of supply lines. But then again, the realism of even those wargames that strive more earnestly for historical accuracy can be and often is exaggerated; those games strike me more as arbitrary systems tweaked to produce the same results as the historical battles they purport to simulate than true simulations in the abstract.

The most important thing Panzer General has going for it is that, historically accurate or not, it’s fun. The interface is quick and well-nigh effortless, while the scenario-based approach assures that you’re only getting the exciting parts of warfare; your forces are already drawn up facing the enemy as each scenario begins. And the game is indeed very attractive to look at, with the flashier elements employed sparingly enough that they never start to annoy.

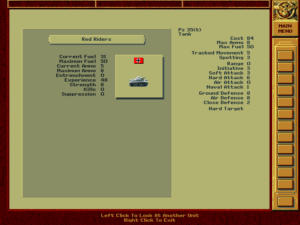

Still, its true secret weapon lies in those aforementioned CRPG elements. Even as you play the role of a German general who collects more and more prestige, accompanied by more and more exciting battlefield assignments, the units you command also move from battle to battle with you, improving their own skills as they go. The effect comes close to matching the identification which X-COM so effectively manages to create between you and your individual soldiers; you can even name your units here, just as you can your soldiers in that other game. You develop a real bond with the units — infantry, artillery, tanks, airplanes, in places even ships — who have fought so many battles for you. You begin to husband them, to work hard to rescue them when they get into a jam, and find yourself fairly shattered — and then fairly livid — when an enemy ambush takes one of them out. You can even mold the makeup of your army to suit your play style to some extent, by choosing which types of units to spend your precious prestige points on. This makes your personal investment in their successes and failures all the greater; the emotional stakes are surprisingly high in this game.

Each scenario in Panzer General begins with some vintage newsreel footage, an approach which has ironically aged much better than the cutting-edge green-screened full-motion-video presentations of so many of its contemporaries. Unlike them, Panzer General has remained an aesthetically attractive game to this day.

The map where all of the actions take place. The game is entirely controlled by clicking on your units and the strip of icons running down the right side of the screen. You can mouse over a unit or icon to see a textual description of its status and/or function at the bottom or top of the screen — as close as any 1995 game got to the tool tips of today. SSI’s overarching priority was to make accessible a genre previously known for its inscrutability.

Clashes between units take place right on the main map, accompanied by little animations which spice up the proceedings without overstaying their welcome.

A unit-information screen, showing not only its raw statistics but a running tally of its battle record. You can name your units and watch them collect experience and battle citations as the war goes on.

You can tailor the makeup of your army by spending prestige points to purchase units that suit your style of play.

While his staff beavered away on Panzer General, Joel Billings continued to cast about for a buyer for his company before it was too late. It wasn’t easy; with the loss of the Dungeons & Dragons license he had lost his most enticing single asset. All of SSI’s core competencies were profoundly out of fashion; CRPGs in general were in the doldrums, and wargames were niche products in an industry that had little shelf space left for anything beyond the broadly popular. Nevertheless, he managed in the end to make a deal.

The backstory leading up to that deal has much to tell us about the waves of mergers and acquisitions that had been sweeping the industry for years by this point. It begins with The Software Toolworks, a company founded by an enterprising kit-computer hacker named Walt Bilofsky all the way back in 1980. He quietly built it into a major player in educational and consumer software over the course of the next decade, by jumping early into the distribution and media-duplication sides of the industry and through two blockbuster products of the sort which don’t attract the hardcore gamer demographic and thus seldom feature in histories like this one, but which had immense Main Street appeal in their day: The Chessmaster 2000 and Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. The combined sales of these two alone exceeded 750,000 units by 1989, the year The Software Toolworks acquired Mindscape.

The latter company was formed in 1983 by one Roger Buoy, and went on to make a name in educational software as well as with innovative games of a slightly intellectual bent: the civilian-spaceflight simulation The Halley Project; a line of bookware text adventures; the early point-and-click graphic adventures developed by ICOM Simulations; Balance of Power, Chris Crawford’s seminal anti-wargame of contemporary geopolitics. Then, too, Mindscape imported and/or distributed many additional games, including those of Cinemaware. But as the decade wound down their bottom line sank increasingly into the red, and in December of 1989 Buoy sold out to The Software Toolworks for $21.5 million.

In the years that followed that acquisition, The Software Toolworks moved into the Nintendo market, releasing many games there under the Mindscape imprint; console titles would make up 42 percent of their overall revenue by 1994. At the same time, they continued to enjoy great success on computers, with the Mavis Beacon series in particular. That entirely fictional typing teacher — a black woman at that, a brave and noble choice to have made in the mid-1980s — became an odd sort of virtual celebrity, with other companies going so far as to ask for her endorsement of their own products, with journalists who joined much of the general public in assuming she was a real person repeatedly asking for interviews. In 1994, The Software Toolworks’s annual sales hit $150 million. On May 12 of that year, the Pearson Group of Britain bought the fast-growing company.

Pearson was a giant of print publishing, both in their homeland and internationally. Formed in 1843 as a construction company, they began buying up magazines and newspapers in the 1920s, building themselves a veritable print empire by the 1970s, with such household names as Penguin Books in their stable. Their sudden plunge into computer software in 1994 was endemic of what we might call the second wave of bookware, when it was widely anticipated that interactive multimedia “books” published on CD-ROM would come to supplement if not entirely supplant the traditional paper-based variety. Bookware’s second wave would last little longer than its first — it would become clear well before the decade’s end that the Internet rather than physical CD-ROMs was destined to become the next century’s preferred method of information exchange — but while it lasted it brought a lot of big companies like the Pearson Group into software, splashing lots of money around in the process; Pearson paid no less than $462 million for The Software Toolworks. Being unenamored with the name of the entity they had just purchased, Pearson changed it — to Mindscape, an imprint that had heretofore represented only a quarter or so of The Software Toolworks’s overall business.

But the wheeling and dealing wasn’t over yet. Within weeks of being themselves acquired, the new Mindscape entered into serious talks with Joel Billings about the prospect of buying SSI. The latter was manifestly dealing from a position of weakness. The Dungeons & Dragons license was gone, as was the reputation SSI had enjoyed during the 1980s as the industry’s premiere maker of strategy games; that crown had been ceded to MicroProse. The only really viable franchise that remained to them was the Tony La Russa Baseball series. Nevertheless, Mindscape believed they saw talent both in SSI’s management and in their technical and creative staff. Said talent was worth taking a chance on, it was decided, given that the price was so laughably cheap. On October 7, 1994, an independent SSI ceased to exist, when Mindscape bought the company for slightly under $2.6 million. Billings was promised that it would be business as usual for most of them in their Sunnyvale, California, office, apart from the quarter of existing staff, mostly working on the sales and packaging side, who were made redundant by the acquisition and would have to be let go.

Once that pain was finished, a rather spectacular honeymoon period began. Mindscape was able to give SSI distribution they could only have dreamed of in the past, getting their games onto the shelves of such mainstream retailers as Office Depot and K-Mart. And in return, SSI delivered Panzer General. Released just a month after the acquisition was finalized, it garnered a gushing five-out-of-five-stars review from Computer Gaming World, who called it “not just a wargame but an adventure” in reference to its uniquely embodied campaign. Add to that its attractive multimedia presentation and its fun and accessible gameplay, then sprinkle over the whole the eternal American nostalgia for all things World War II, and you had a recipe for one of the breakout hits of that Christmas season — the first example of same which SSI had had since Eye of the Beholder back in 1991. Helped along no doubt by Mindscape’s distributional clout, it went on to sell more than 200,000 copies in its first fifteen months. Eventually it surpassed even the sales figures of Pool of Radiance to become SSI’s most popular single game ever. In fact, Panzer General still stands today as the most successful computerized wargame in history.

The game’s success was positively thrilling for Joel Billings, now ensconced as a “regular, full-time employee” of Mindscape, complete with a 401(k) plan and eligibility for the Executive Bonus Plan. His real passion had always been wargames; those were, after all, the games he had originally founded his company in order to make. To have come full circle here at the end of SSI’s independent existence, and to have done so in such smashing fashion at that, felt like a belated vindication. There was only one slight regret to mar the picture. “I wonder what would have happened if Panzer General had come out before the Mindscape acquisition…” he can’t help but muse today.

Taken as a whole, Panzer General deserved every bit of its success: it was and is a fine game. For some of us then and now, there is only one fly in the ointment: we have no desire to play a Nazi. I’ll return to a range of issues which Panzer General raises about the relationship of games to the real world and to our historical memory in my next article. For today, however, I have another story to finish telling.

To say that Mindscape was initially pleased with their new acquisition hardly begins to state the case. “We rocketed!” thanks to Panzer General, remembers Billings: “Mindscape loved us!” And why not? As an in-house-developed original product with no outside royalties whatsoever to pay on its huge sales, Panzer General alone recouped two and a half times the cost of purchasing SSI in its first year on the market. A set of three shovelware collections which between them included all of the old Gold Box Dungeons & Dragons CRPGS also did surprisingly well, selling more than 100,000 profit-rich copies in all before the final expiration of even SSI’s non-exclusive deal with TSR forced them off the market on July 1, 1995.

In the longer run, however, the mass-market ambitions of Mindscape proved a poor fit with the nichey tradition of SSI. To save production costs and capitalize on the success of Panzer General, SSI used its engine as the basis of a 5-Star General series, first presenting World War II from the perspective of an Allied general in Europe, then moving farther afield to a high-fantasy setting, to outer space, to World War II in the Pacific. Although those games certainly had their fans — Fantasy General in particular is fondly remembered today — the overall trend line was dismayingly similar to that of the Gold Box games: a rather brilliant initial game followed by a series of increasingly rote sequels running inside an increasingly decrepit-seeming engine, resulting in steadily decreasing sales figures. By the time the engine was updated for Panzer General II, People’s General, Panzer General III, and, Lord help us, Panzer General 3D Assault, a distinct note of desperation was peeking through. SSI’s other attempts to embrace the mass-market, such as a series of real-time strategy games based on the tabletop-miniatures game Warhammer, felt equally sterile, as if their hearts just weren’t in it.

Certainly Joel Billings personally found the mainstream market to be less than congenial. In February of 1996, he was promoted to become the head of Mindscape’s entire games division, but found himself completely out of his depth there. Within six months, he asked for and was granted a demotion, back to being merely the head of SSI.

But even SSI was no longer the place it once had been; it seemed to lose a little more of its identity with each passing year, as the acquisitions and consolidations continued around it. Mindscape was bought by The Learning Company in 1998, after Pearson’s realization that software — at least software shipped on physical media — was not destined to be the future of publishing writ large. Then Mattel bought The Learning Company in 1999. They closed SSI’s Sunnyvale offices the following year, keeping the name as a brand only. That same year, they sold The Learning Company once again, to the Gores Technology Group, who then turned around and sold all of the gaming divisions to the French publisher Ubisoft in 2001. SSI was now a creaky anachronism in Ubisoft’s trendy lineup. The last game to ship with the SSI name on its box was Destroyer Command, in February of 2002 — almost exactly 22 years after a young Joel Billings had first started calling computer stores to offer them something called Computer Bismark.

Billings himself was long gone by 2002, cast adrift with the final closing of SSI’s Sunnyvale offices. Thoroughly fed up with the mainstream-gaming rat race, he returned to the only thing he had ever truly wanted to do, making and selling his beloved wargames. For almost two decades now he’s run 2 By 3 Games with Gary Grigsby and Keith Brors, two designers and programmers from the salad days of SSI. They make absurdly massive, gleefully complex, defiantly inaccessible World War II wargames, implemented at a level of depth and breadth of which SSI could only have dreamed. And, thanks to the indie revolution in games and the wonders of digital distribution, they manage to sell enough of them to keep at it. Good for them, I say.

Melancholy though SSI’s ultimate fate proved to be, they did outlive their erstwhile partners TSR. After flooding their limited and slowly shrinking market of active Dungeons & Dragons players with way too many campaign settings and rules supplements during the first half of the 1990s, TSR saw the chickens come home to roost right about the time they parted ways with SSI, when sales of the paperback novels that had done much to sustain them to this point also began to collapse. For all that they had never been anyone’s idea of literary masterpieces, the early Dungeons & Dragons novels had been competently plotted, fast-paced reads that more than satisfied their target demographic’s limited expectations of them. For years, though, editorial standards there as well had been slowly falling, and it seemed that readers were finally noticing. After the Christmas season of 1996, Random House, who distributed all of TSR’s products to the bookstore trade, informed them that they would be returning millions of dollars worth of unsold books and games. TSR lacked the cash to pay Random House, as they did to print more product. And, laboring under a serious debt load already, they found there was no one willing to lend them any more money. They were caught in a classic corporate death spiral.

The savior that emerged was welcome in its way — any port in a storm, right? — but also deeply humiliating. Wizards of the Coast, the maker of the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering which had done so much to decimate TSR’s Dungeons & Dragons business in recent years, now bought their victim from Lorraine Williams for about $30 million, with much or most of that sum going to repay of the debts TSR had accrued.

Still, TSR’s final humiliation proved a welcome development on the whole for their most famous game; in the eyes of most gamers, Wizards became a better steward of Dungeons & Dragons than TSR had been for a long time if ever. They cut back on the fire hose of oft-redundant product, whilst streamlining the rules for new editions of the game that were more intuitively playable than the old. Ironically, many of the new approaches were ported back to the tabletop from digital iterations of Dungeons & Dragons, which themselves found a new lease on life with Interplay’s massive hit Baldur’s Gate in 1998. Meanwhile the “open gaming” D20 license, which Wizards of the Coast launched with great fanfare along with the official third edition of Dungeons & Dragons in 2000, drew from the ideals of open-source software. While tabletop Dungeons & Dragons would have its ups and downs under Wizards of the Coast, it would never again descend to the depths it had plumbed in 1997. A world without Dungeons & Dragons now seems all but unimaginable; in 1997, it was all too real a prospect.

All of which is to say that Dungeons & Dragons will continue to be a regular touchstone here as we continue our voyage through gaming history. Whether the computerized versions of the game that came after the end of an independent TSR and SSI are up to the standards of the Gold Box line is of course a matter of opinion. But one thing cannot be debated: the story of Dungeons & Dragons and computers is far from over.

(Sources: As with all of my SSI articles, much of this one is drawn from the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Other sources include the book Designers and Dragons, ’70 to ’79 by Shannon Appelcline; Computer Gaming World of June 1994, September 1994, December 1994, and January 1995; PC Review of June 1992; Retro Gamer 94 and 198; Chicago Tribune of December 2 1985 and December 6 1989; New York Times of June 13 1994. Online sources include Matt Barton’s interview with Joel Billings, the Video Game Newsroom Time Machine interview with Joel Billings, and the Mental Floss “profile” of the fictional Mavis Beacon.

Oddly given its popularity back in the day and its ongoing influence on computer wargaming, the original Panzer General has not been re-released for digital distribution; this is made doubly odd by the fact that some of the less successful later games in the 5-Star General series have been re-released. It’s too large for me to host here even if I wasn’t nervous about the legal implications of doing so, but I have prepared a stub of the game that’s ready to go if you just add to the appropriate version of DOSBox for your platform of choice and an ISO image of the CD-ROM. A final hint: as of this writing, you can find the latter on archive.org if you look hard enough.)