X-COM seemed to come out of nowhere. Its release was not preceded by an enormous marketing campaign with an enormous amount of hype. It had no video demo playing in the front window of Babbages, it wasn’t advertised twelve months in advance on glossy foldout magazine inserts, it had no flashing point-of-purchase kiosks. It didn’t come in a box designed by origamists from the school of abstract expressionism. It featured no full-motion video starring the best TV actors of the 80s; it had no voice-overs. It offered neither Super VGA graphics, nor General MIDI support. It wasn’t Doom-like, Myst-like, or otherwise like a hit game from the previous season; it didn’t steal the best features from several other successful games. It wasn’t even on a CD-ROM!

In short, if you plugged X-COM’s variables into the “success formula” currently in use by the majority of large game companies, you’d come up with a big, fat goose egg. According to the prevailing wisdom, there’s no way X-COM could survive in today’s gaming marketplace. And yet it sold and sold, and gamers played on and on.

— Chris Lombardi, writing in the April 1995 issue of Computer Gaming World

In the early days of game development, there existed little to no separation between the roles of game programmer and game designer. Those stalwart pioneers who programmed the games they themselves designed could be grouped into two broad categories, depending on the side from which they entered the field. There were the technologists, who were fascinated first and foremost with the inner workings of computers, and chose games as the most challenging, creatively satisfying type of software to which they could apply their talents. And then there were those who loved games themselves above all else, and learned to program computers strictly in order to make better, more exciting ones than could be implemented using only paper, cardboard, and the players’ imaginations. Julian Gollop, the mastermind behind the legendary original X-COM, fell most definitely into this latter category. He turned to the computer only when the games he wanted to make left him no other choice.

Growing up in the English county of Essex, Julian and his younger brother Nick lived surrounded by games, courtesy of their father. “Every Christmas, we didn’t watch TV, we’d play games endlessly,” Julian says. From Cluedo, they progressed to Escape from Colditz, then on to the likes of Sniper! and Squad Leader.

Julian turned fifteen in 1980, the year that the Sinclair ZX80 arrived to set off a microcomputer fever all across Britain, but he was initially immune to the affliction. Unimpressed by the simplistic games he saw being implemented on those early machines, which often had as little as 1 K of memory, he started making his own designs to be played the old-fashioned way, face-to-face around a tabletop. It was only when he hit a wall of complexity with one of them that he reassessed the potential of computers.

The game in question was called Time Lords; as the name would imply, it was based on the Doctor Who television serials. It asked two to five players to travel through time and space and alter the course of history to their advantage, but grew so complex that it came to require an additional person to serve in the less-than-rewarding capacity of referee.

By this point, it was 1982, and a friend of Julian’s named Andy Greene had acquired one of the first BBC Micros. Its relatively cavernous 32 K of memory opened up the possibility of using the computer as a referee instead of a bored human. Greene coded up the program in BASIC, staying faithful to Julian’s board game to the extent of demanding that players leave the room when it wasn’t their turn, so as not to see anything they weren’t supposed to of their opponents’ actions. The owner of the tabletop-games store where Julian shopped was so impressed with the result that he founded a new company, Red Shift Games, in order to publish it. They all traveled to computer fairs together, carrying copies of the computerized Time Lords packaged in Ziploc baggies. The game didn’t take the world by storm — Personal Computer News, one of the few publications to review it, pronounced it a “bored game” instead of a board game — but it was a start.

The two friends next made Islandia, another multiplayer strategy game of a similar stripe. In the meantime, Julian acquired a Sinclair Spectrum, the cheap and cheerful little machine destined to drive British computer gaming for the next half-decade. Having now a strong motivation to learn to program it, Julian did just that. His first self-coded game, and his first on the Spectrum, appeared in 1984 in the form of Nebula, a conquer-the-galaxy exercise that for the first time offered a computer opponent to play against.

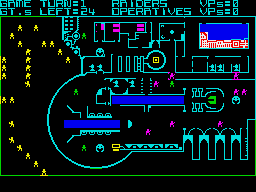

The artificial intelligence disappeared again from his next game, but it mattered not at all. Rebelstar Raiders was the prototype for Julian Gollop’s most famous work. In contrast to the big-picture strategy of his earlier games, it focused on individual soldiers in conflict with one another in a Starship Troopers-like science-fictional milieu. Still, it was very much based on the board games he loved; there was a lot of Sniper! and Squad Leader in its turn-based design. Despite being such a cerebral game, despite being one that you couldn’t even play without a mate to hand, it attracted considerable attention. Red Shift faded out of existence shortly thereafter as its owner lost interest in the endeavor, but Rebelstar Raiders had already made Julian’s reputation, such that other publishers were now knocking at his door.

Rebelstar Raiders, the first of Julian Gollop’s turn-based tactical-combat games. Ten years later, the approach would culminate in X-COM.

It must have been a thrill for Julian Gollop the board-game fanatic when Games Workshop, the leading British publisher of hobbyist tabletop games, signed him to make a computer game for their new — if ultimately brief-lived — digital division. Chaos, a spell-slinging fantasy free-for-all ironically based to some extent on a Games Workshop board game known as Warlock — not that Julian told them that! — didn’t sell as well as Rebelstar Raiders, although it has since become something of a cult classic.

So, understandably, Julian went where the market was. Between 1986 and 1988, he produced three more iterations on the Rebelstar Raiders concept, each boasting computer opponents as well as multiplayer options and each elaborating further upon the foundation of its predecessor. Game designers are a bit like authors in some ways. Some authors — like, say, Margaret Atwood — try their hands at a wide variety of genres and approaches, while others — like, say, John Cheever — compulsively sift through the same material in search of new nuggets of insight. Julian became, in the minds of the British public at least, an example of the Cheever type of designer. “It could be said by the cruelest among us that Julian has only ever written one game,” wrote the magazine New Computer Express in 1990, “but has released various substantially enhanced versions of it over the years.”

Of those enhanced versions, Julian published Rebelstar and Rebelstar 2: Alien Encounter through Firebird as a lone-wolf developer, then published Laser Squad through a small outfit known as Blaze Software. Before he made this last game, he founded a company called Target Games — soon to be renamed to the less generic Mythos Games — with his father as silent partner and his brother Nick in an active role; the latter had by now become an accomplished programmer in his own right, in fact surpassing Julian’s talents in that area. In 1990, the brothers made the Chaos sequel Lords of Chaos together in order to prove to the likes of New Computer Express that Julian was at least a two-trick pony. And then came the series of events that would lead to Julian Gollop, whose games were reasonably popular in Britain but virtually unknown elsewhere, becoming one of the acknowledged leading lights of strategy gaming all over the world.

The road to X-COM traveled through the terrain of happenstance rather than any master plan. Julian’s career-defining project started as Laser Squad 2 in spirit and even in name, the next manifestation of his ongoing obsession with small-scale, turn-based, single-unit tactics. The big leap forward this time was to be an isometric viewpoint, adding an element of depth to the battlefield. He and Nick coded a proof of concept on an Atari ST. While they were doing so, Blaze Software disappeared, yet another ephemeral entity in a volatile industry. Now, the brothers needed a new publisher for their latest game.

Both of them had been playing hours and hours of Railroad Tycoon, from the American publisher MicroProse. Knowing that MicroProse had a British branch, they decided to take their demo there first. It was a bold move in its way; as I’ve already noted, their games were popular in their sphere, but had mostly borne the imprints of smaller publishers and had mostly been sold at cheaper price points. MicroProse was a different animal entirely, carrying with it the cachet that still clung in Europe to American games, with their bigger budgets and higher production values. In their quiet English way, the Gollops were making a bid for the big leagues.

Luckily for them, MicroProse’s British office was far more than just a foreign adjunct to the American headquarters. It was a dynamic, creative place in its own right, which took advantage of the laissez-faire attitude of “Wild” Bill Stealey, MicroProse’s flamboyant fly-boy founder, to blaze its own trails. When the Gollops brought in the nascent Laser Squad 2, they were gratified to find that just about everyone at MicroProse UK already knew of them and their games. Peter Moreland, the head of development, was cautiously interested, but with plenty of caveats. For one thing, they would need to make the game on MS-DOS rather than the Atari ST in order to reach the American market. For another, a small-scale tactical-combat game alone wouldn’t be sufficient — wouldn’t be, he said, “MicroProse enough.” After making their name in the 1980s with Wild Bill’s beloved flight simulators, MicroProse was becoming at least as well known in this incipient new decade for grand-strategy games of or in the spirit of their star designer Sid Meier, like the aforementioned Railroad Tycoon and the soon-to-be-released Civilization. The emphasis here was on the “grand.” A Laser Squad 2 just wouldn’t be big enough for MicroProse.

Finally, Moreland wasn’t thrilled by all these far-future soldiers fighting battles in unknown regions of space for reasons that were abstract at best. Who could really relate to any of that? He wanted something more down to earth — literally. Maybe something to do with alien visitors in UFOs… that sort of thing. Julian nodded along, then went home to do some research and refine his proposal.

He quickly learned that he was living in the midst of a fecund period in the peculiar field of UFOlogy. In 1989, a sketchy character named Bob Lazar had given an interview for a Las Vegas television station in which he claimed to have been employed as a civilian contractor at the top-secret Nevada military base known only as Area 51. In that location, so he said, the American Air Force was actively engaged in testing fantastic technologies derived from extraterrestrial visitors. The interview would go down in history as the wellspring of a whole generation of starry-eyed conspiracy theorists, whose outlandish beliefs would soon enter the popular media zeitgeist via such vehicles as the television series The X-Files. When Julian first investigated the subject in 1991, however, UFOs and aliens were still a fairly underground obsession. Nevertheless, he took much from the early lore and legends of Area 51, such as a supposed new chemical element — called ununpentium by Lazar, elerium by the eventual game — which powered the aliens’ spaceships.

His other major source of inspiration was the 1970 British television series entitled simply UFO. In fact, his game would eventually be released as UFO: Enemy Unknown in Europe, capitalizing on the association with a show that a surprising number of people there still remembered. (I’ve chosen to use the American name of X-COM globally in this article because all subsequent games in the franchise would be known all over the world under that name; it has long since become the iconic one.) UFO the television series takes place in the then-near-future of 1980, when aliens are visiting the Earth in ever-increasing numbers, abducting humans and wreaking more and more havoc. An international organization known as SHADO (“Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation”) has been formed to combat the menace. The show follows the exploits of the SHADO operatives, complete with outlandish “futuristic” costumes and sets and gloriously cheesy special effects. Gollop lifted this basic scenario and moved it to his own near-future: to the year 1999, thus managing to nail not only his decade’s burgeoning obsession with aliens but also its unease about the looming millennium.

The game is divided into two distinct halves — so much so that each half is almost literally an entirely separate game: each unloads itself completely from memory to run a separate executable file at the point of transition, caching on the hard drive before doing so the relatively small amount of state data which its companion needs to access.

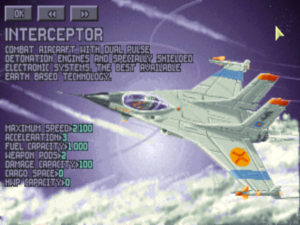

The first part that you see is the strategic level. As the general in charge of the “Extra-Terrestrial Combat Force,” or X-COM — the name was suggested by Stephen Hand and Mike Brunton, two in-house design consultants at MicroProse UK — you must hire soldiers and buy equipment for them; research new technologies, a process which comes more and more to entail reverse-engineering captured alien artifacts in order to use your enemy’s own technology against them; build new bases at strategic locations around the world, as well as improve your existing ones (you start with just one modest base); and send your aircraft out to intercept the alien craft that are swarming the Earth. In keeping with the timeless logic of computer games, the countries of the Earth have chosen to make X-COM, the planet’s one real hope for defeating the alien menace, into a resource-constrained semi-capitalist enterprise; you’ll often need to sell gadgets you’ve manufactured or stolen from the aliens in order to make ends meet, and if you fail to perform well your sponsoring countries will cut their funding.

The “Geoscape” view, where you place your bases and use them to intercept airborne alien attackers. You can find a wealth of discussion online about where best to position your first base — but naturally, most people prefer to put it in their home town. Like the ability to name your individual soldiers, the ability to start right in your own backyard forges a personal connection between the game and its player.

This half of the game was a dizzying leap into uncharted territory for the Gollop brothers. Thankfully, then, they were on very familiar ground when it came to the other half: the half that kicks in when your airborne interceptors force a UFO to land, or when you manage to catch the aliens in the act of terrorizing some poor city, or when the aliens themselves attack one of your bases. Here you find yourself in what amounts to Laser Squad 2 in form and spirit if not in name: an ultra-detailed turn-based single-unit combat simulator, the latest version of a game which Julian Gollop had already made four times before. (Or close enough to it, at any rate: X-COM, the culmination of what had begun with Rebelstar Raiders on the Spectrum, is ironically single-player only, whereas that first game had not just allowed but required two humans to play.) Although the strategic layer sounds far more complex than this tactical layer — and, indeed, it is in certain ways — it’s actually the tactical game where you spend the majority of your time, fighting battles which can consume an entire evening each.

For all their differences, the two halves of the game do interlock in the end as two facets of a whole. Your research efforts, equipment purchases, and hiring practices in the strategic half determine the nature of the force you lead into the tactical man-against-alien battles. Less obviously but just as significantly, your primary reward for said battles proves to be the recovery of alien equipment, alien corpses, and even live alien specimens (all is fair in love and genocidal interplanetary war), which you cart back to your bases to place at the disposal of your research teams. And so the symbiotic relationship continues: your researchers use what you recover as grist for their mill, which lets you go into tougher battles with better equipment to hand, thereby to bring back still richer spoils.

The capsule description of the finished game which I’ve just provided mirrors almost perfectly the proposal which Julian Gollop delivered to MicroProse; the design would change surprisingly little in the process of development. MicroProse thought it sounded just fine as-is.

The contract which the Gollops signed with MicroProse specified that the former would be responsible for all of the design and coding, while the latter would provide the visual and audio assets. MicroProse UK did hold up their end of the bargain, but had an oddly casual attitude toward the project in general. Julian remembers their producer as “very laid back — he would come over once a month, we would go to the pub, talk about the game for a bit, and he would go home.” Otherwise, the Gollops worked largely alone after their first rush of consultations with the MicroProse mother ship had faded into the past. Time dragged on and on while they struggled with this massively complicated game, one half of which was unlike anything they had ever even contemplated before.

X-COM‘s UFOpaedia is a direct equivalent to Civilization‘s innovative Civilopedia, its most obvious single nod to Sid Meier’s equally influential but very, very different game.

As it did so, much happened in the broader world of MicroProse. On the positive side, Sid Meier’s Civilization was released at the end of 1991. But despite this and some other success stories, MicroProse’s financial foundation was growing ever more shaky, as their ambitions outran their core competencies. The company lost millions on an ill-judged attempt to enter the stand-up arcade market, then lost millions more on baroque CRPGs and flashy interactivity-lite adventure games. After an IPO that was supposed to bail them out went badly off the rails, Wild Bill Stealey sold out in June of 1993 to Spectrum Holobyte, another American publisher. The deal seemed to make sense: Spectrum Holobyte had a lot of money, thanks not least to generous venture capitalists, but a rather thin portfolio of games, while MicroProse had a lot of games both out and in the pipeline but had just about run out of money.

Spectrum Holobyte sifted carefully through their new possession’s projects in development, passing judgment on which were potential winners and which certain losers. According to Julian Gollop, Spectrum Holobyte told MicroProse UK in no uncertain terms to cancel X-COM. On the face of it, it wasn’t an unreasonable point of view to take. The Gollops had been working for almost two years by this point, and still had few concrete results to show for their efforts. It really did seem that they were hopelessly out of their depth. Luckily for them, however, Peter Moreland and others in the British office still believed in them. They nodded along with the order to bin X-COM, then quietly kept the project on the books. At this point, it didn’t cost them much of anything to do so; the art was already done, and now it was up to the Gollops to sink or swim with it.

X-COM bobbed up to the surface six months later, when the new, allegedly joint management team — Stealey would soon leave the company, feeling himself to have been thoroughly sidelined — started casting about for a game to feature in Europe in the first quarter of 1994, thereby to make the accountants happy. Peter Moreland piped up sheepishly: “You remember that UFO project you told us to cancel? Well, it’s actually still kicking around…” And so the Gollop brothers, who had been laboring under strangely little external pressure for the past 26 months or so, were now ordered to get their game done already. They managed it, just — UFO: Enemy Unknown shipped in Europe in March of 1994 — but some of the problems in the finished game definitely stem from the deadline that was so arbitrarily imposed from on high.

But if the game could have used a few more months in the oven, it nonetheless shipped in better condition than many other MicroProse games had during the recent stretch of financial difficulties. It garnered immediate rave reviews, while its sales also received a boost from another source. The first episode of The X-Files had aired the previous September in the United States, followed by airings across Europe. Just like that, a game about hostile alien visitors seemed a lot more relevant. Indeed, the game possessed much the same foreboding atmosphere as the show, from its muted color palette to MicroProse composer John Broomhall’s quietly malevolent soundtrack, which he had created in just two months in the final mad rush up to the release deadline. He couldn’t have done a better job if he’d had two years.

X-COM: UFO Defense shipped a few months later in North America, into a cultural zeitgeist that was if anything even more primed for it. Computer Gaming World, the American industry’s journal of record, gave it five stars out of five, and its sales soared well into the six digits. As the quote that opened this article attests, X-COM was in many ways the antithesis of what most publishers believed constituted a hit game in the context of 1994. Its graphics were little more than functional; it had no full-motion video, no real-time 3D rendering, no digitized voices; it fit perfectly well on a few floppy disks, thank you very much, with no need for any new-fangled CD-ROM drive. And yet it sold better than the vast majority of those other “cutting-edge” games. Many took its success as a welcome sign that gaming hadn’t yet lost its soul completely — that good old-fashioned gameplay could still trump production values from time to time.

The original X-COM‘s reputation has only grown more hallowed in the years since its release. It’s become a perennial on best-games-of-all-time lists, even ones whose authors weren’t yet born at the time of its release. For this is a game, so we’re told, that transcends its archaic presentation, that absolutely any student of game design needs to play.

That’s rather ironic in that X-COM is a game that really shouldn’t work at all according to many of the conventional rules of design. For example, it’s one of the most famous of all violators of what’s become known as the Covert Action Rule, as formulated by Sid Meier and named after one of his own less successful designs. The rule states that pacing is as important in a strategy game as it is in any other genre, that “mini-games” which pull the player away from the overarching strategic view need to be short and to the point, as is the case in Meier’s classic Pirates!. If they drag on too long, Meier tells us, the player loses focus on the bigger picture, forgets what she’s been trying to accomplish there, gets pulled out of that elusive state of “flow.”

But, as I already noted, X-COM‘s tactical battles can drag on for an hour or two at a time — and no one seems be bothered by this at all. What gives?

By way of an answer to that question, I would first note that the Covert Action Rule is, like virtually all supposedly hard-and-fast rules of game design, riddled with caveats and exceptions. (Personally, I don’t even agree that violating the yet-to-be-formulated Covert Action Rule was the worst problem of Covert Action itself.) And I would also note that X-COM does at least a couple of things extraordinarily well as compensation, better than any strategy game that came before it. Indeed, one can argue that no earlier grand-strategy game even attempted to do these things — not, at least, to anything like the same extent. Interestingly, both inspired strokes are borrowed from other gaming genres.

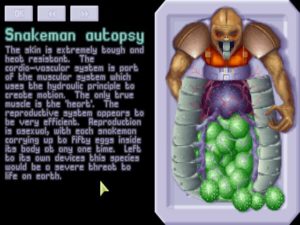

The first is the intriguing mystery surrounding the aliens, which is peeled back layer by layer as you progress. As your scientists study the equipment and alien corpses brought back from the battle sites and interrogate the live aliens your soldiers have captured, you learn more and more about where your enemies come from and what motivates them to attack the Earth so relentlessly. It doesn’t take long to reach a point where you look forward to the next piece of this puzzle as excitedly as you do the next cool gun or piece of armor. By the time the whole experience culminates in a desperate attack on the aliens’ home base, you’re all in. Granted, a byproduct of this sense of unfolding discovery is that you may not feel like revisiting the game after you win; for many or most of us, this is a strategy game to play through once rather than over and over again. But on the other hand, considering the fifty hours or more it will take you to get through it once, it’s hard to complain overmuch about that fact. Needless to say, when you do play it for the first time you should meticulously avoid spoilers about What Is Really Going On Here.

Learning more about the alien invaders via an autopsy. The game was ahead of its time; the year after X-COM‘s release, at the height of the X-Files-fueled UFO craze, the Fox television channel would broadcast Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction? in the United States. (For the record, it was most assuredly the latter.)

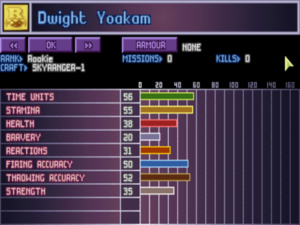

X-COM‘s other, even more brilliant stroke is the sense of identification it builds between you and the soldiers you send into battle. Each soldier has unique strengths and weaknesses, forcing you to carefully consider the role she plays in combat: a burly, fearless character who can carry enough weaponry to outfit your average platoon but couldn’t hit the proverbial broad side of a barn must be handled in a very different way from a slender, nervous sharpshooter. As your soldiers (hopefully) survive missions, their skills improve, CRPG-style. Thus you have plenty of practical reasons to be more loathe to lose a seasoned veteran than a greenhorn fresh out of basic training. And yet this purely zero-sum calculus doesn’t fully explain why each mission is so nail-bitingly tense, so full of agonizing decisions balancing risk against reward.

One of X-COM‘s most defining design choices is also one of its simplest: it lets you name each soldier for yourself. As you play, you form a picture of each of them in your imagination, even though the game itself never describes any of them to you as anything other than a list of numbers. Losing a soldier who’s been around for a while feels weirdly like losing a genuine acquaintance. For here too you can’t help but embellish the thin scaffolding of fact the game provides with your own story of what happened: the grizzled old-timer who went out one time too many, whose nerves just couldn’t handle another firefight; the foolhardy, testosterone-addled youth who threw himself into every battle like he was indestructible, until one day he wasn’t. X-COM provides the merest glimpse of what it must feel like to be an actual commander in war: the overwhelming stress of having the lives of others hanging on your decisions, the guilty second-guessing that inevitably goes on when you lose someone. It has something that games all too often lack: a sense of consequences for your actions. Theoretically at least, the best way to play it is in iron-man mode: no saving and restoring to fix bad outcomes, dead is dead, own your decisions as commander.

Beginning with just a name you choose for yourself and a handful of statistics which the game provides, your imagination will conjure a whole personality for each of your soldiers. Dwight here, for example, likes guitars, Cadillacs, and hillbilly music.

In one of those strange concordances that tend to crop up in many creative fields, X-COM wasn’t the only strategy game of 1994 to bring in CRPG elements to great effect. Ironically, these innovations occurred just as the CRPG genre itself was in its worst doldrums since Ultima I and Wizadry I had first brought it to prominence. Today, even as the CRPG has long since regained its mojo as a gaming genre, CRPG elements have become the special sauce ladled over a wide array of other types of games. X-COM was among the first to show how tasty the end result could be.

I have to say, however, that I find other elements of X-COM less appetizing, and that its strengths don’t quite overcome its weaknesses in my mind sufficiently to win it a place on my personal list of best games ever. My first stumbling block is the game’s learning curve, which is not just steep but unnecessarily so. I’d like to quote Garth Deangelis, who led the team that created XCOM: Enemy Unknown, the critically acclaimed franchise reboot that was released in 2012:

While [the original X-COM] may have been magnificent, it was also a unique beast when it came to beginning a new game. We often joked that the diehards who mastered the game independently belonged to an elite club because by today’s standards the learning curve was like climbing Mount Everest.

As soon as you fire up the original, you’re placed in a Geoscape with the Earth silently looming, and various options to explore within your base — including reading (unexplained) financial reports, approving manufacturing requests (without any context as to what those would mean later on), and examining a blueprint (which hinted at the possibility for base expansion), for example — the player is given no direction.

Even going on your first combat mission can be a bit of a mystery (and when you first step off the Skyranger, the game will kill off a few of your soldiers before you even see your first alien — welcome to X-COM!).

There’s certainly a place for complex games, and complexity will always come complete with a learning curve of some sort. But, again, X-COM‘s curve is just unnecessarily steep. Consider: when you begin a new game, you have two interceptors already in your hangar for bringing down UFOs. Fair enough. Unfortunately, they come equipped with sub-optimal Stingray missiles and borderline-useless cannon. So, one of the first tasks of the experienced player becomes to requisition some more advanced Avalanche missiles, put them on her interceptors, and sell off the old junk. Why can the game not just start you off with a reasonable weapons load-out? A similar question applies to the equipment carried by your individual soldiers, as it does to the well-nigh indefensible layout of your starting base itself, which makes it guaranteed to fall to the first squad of marauding aliens who come calling. The new player is likely to assume, reasonably enough, that the decisions the game has already made for her are good ones. She finds out otherwise only by being kicked in the teeth as a result of them. This is not good game design. The impression created is of a game that is not tough but fair, but rather actively out to get her.

Your starting base layout. By no means should you assume that this is a defensible one. In fact, many players spend a lot of money at the very beginning ripping it up completely and starting all over again. Why should this be necessary?

You’ll never use a large swath of the subpar weapons and equipment included in X-COM, which rather begs the questions what they’re doing in there. The game could have profited greatly from an editor empowered to pare back all of this extraneous nonsense and home in on its core appeal. Likewise, the user interface in the strategic portion operates on the principle that, if one mouse click is good, ten must be that much better; everything is way more convoluted than it needs to be. Just buying and selling equipment is agonizing.

The tactical game’s interface is also dauntingly complex, but does have somewhat more method to its madness, being the beneficiary of all of Julian Gollop’s earlier experience with this sort of game. Still, even tactical combat, so widely and justly lauded as the beating heart of X-COM, is not without its frustrations. Certainly every X-COM player is all too familiar with the last-alien-on-the-map syndrome, where you sometimes have to spend fifteen or twenty minutes methodically hunting the one remaining enemy, who’s hunkered down in some obscure corner somewhere. The nature of the game is such that you can’t relax even in these situations; getting careless can still get one or more of your precious soldiers killed before you even realize what’s happening. But, although perhaps a realistic depiction of war, this part of the game just isn’t much fun. The problem is frustrating not least because it’s so easily soluble: just have the remaining aliens commit suicide to avoid capture — something entirely in keeping with their nature — when their numbers get too depleted.

All of these niggling problems mark X-COM as the kind of game I have to rant about here all too often: the kind that was never actually played before its release. For all its extended development time, it still needed a few more months filled with play-testing and polishing to reach its full potential. X-COM‘s most infamous bug serves as a reminder of just how little of either it got: its difficulty levels are broken. If you select something other than the “beginner” difficulty, it reverts back to the easiest level after the first combat mission. In one sense, this is a blessing: the beginner difficulty is more than difficult enough for the vast majority of players. On the other, though… how the heck could something as basic as that be overlooked? There’s only one way that I can see: if you barely played the game at all before you put it in a box and shipped it out the door.

To his credit, Julian Gollop himself is well aware of these issues and freely acknowledges them — does so much more freely in fact than some of his game’s biggest fans. He notes the influence of vintage Avalon Hill and SPI board games, some of which were so demanding that just being able to play them at all — never mind playing them well — was an odd sort of badge of honor for the grognards of the 1970s and early 1980s. He would appear to agree with me that there’s a bit too much of their style of complexity-for-its-own-sake in X-COM:

I believe that a good game may have relatively simple rules, but have complex situations arise from them. Strategy games tend to do that very well, you know — even the simplest ones are very good at that. I think it’s possible to have an accessible game which doesn’t have amazingly complex rules, but still has a kind of emerging complexity within what happens — you know, what players do, what players explore. For me, that’s the Holy Grail of game design. So, I don’t think that I would probably go back to making games as complex as [X-COM].

Like poets, game designers often simplify their work as they age, the better to capture the real essence of what they’re trying to express.

But whatever their final evaluation of the first game, most players then and now would agree that few franchises have been as thoroughly botched by their trustees as X-COM was afterward. When the first X-COM became an out-of-left-field hit, MicroProse UK, who had great need of hits at the time to impress the Spectrum Holobyte brass, wanted the Gollops to provide a sequel within a year. Knowing that that amount of time would allow them to do little more than reskin the existing engine, they worked out a deal: they would give their publisher their source code and let them make a quickie sequel in-house, while they themselves developed a more ambitious sequel for later release.

The in-house MicroProse project became 1995’s X-COM: Terror from the Deep, which posited that, forty years after their defeat at the end of the first game, the aliens have returned to try again. The wrinkle this time is that they’ve set up bases under the Earth’s oceans, which you must attack and eradicate. Unfortunately, Terror from the Deep does little to correct the original’s problems; if anything, it makes them worse. Most notably, it’s an even more difficult game than its predecessor, a decision that’s hard to understand on any level. Was anyone really complaining that X-COM was too easy? All in all, Terror from the Deep is exactly the unimaginative quickie sequel which the Gollops weren’t excited about having to make.

Nevertheless, it’s arguably the best of the post-original, pre-reboot generation of X-COM games. X-COM: Apocalypse, the Gollops’ own sequel, was a project on a vastly greater scale than the first two X-COM games, a scale to which they themselves struggled to adapt. It was riven by bureaucratic snafus and constant conflict between developer and publisher, and the resulting process of design-by-fractious-committee turned it into a game that did a lot of different things — turn-based and real-time combat in the very same game! — but did none of them all that well, nor even looked all that good whilst doing them. Julian Gollop today calls it “the worst experience of my entire career” and “a nightmare.” He and Nick cut all ties with MicroProse after its 1997 release.

After that, MicroProse lost the plot entirely, stamping the X-COM label onto games that had virtually nothing in common with the first one. X-COM: Interceptor (1998) was a space simulator in the mode of Wing Commander; Em@il Games: X-COM (1999) was a casual multiplayer networked affair; X-COM: Enforcer (2001) was a mindless shoot-em-up. This last proved to be the final straw; the X-COM name disappeared for the next eleven years, until XCOM: Enemy Unknown, the reboot by Firaxis Games.

If you ask me, said reboot is in absolute terms a better game than the original, picking up on almost all of its considerable strengths while eliminating most of its weaknesses. But it cannot, of course, lay claim to the same importance in the history of gaming. Despite its flaws, the original X-COM taught designers to personalize strategy games, showed them how to raise the emotional stakes in a genre previously associated only with cool calculation. For that reason, it richly deserves its reputation as one of the most important games of its era.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Video Games Conquered the World by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene; Amstrad Action of October 1989; Computer Gaming World of August 1994, September 1994, April 1995, and July 1995; Crash of Christmas 1988 and May 1989; Game Developer of April 2013; Retro Gamer 13, 68, 81, 104, 106, 112, and 124; Amiga Format of December 1989, June 1994, and November 1994; Computer and Video Games of December 1988; Games TM 46; New Computer Express of September 15 1990; Games Machine of July 1988; Your Sinclair of August 1990 and September 1990; Personal Computer News of July 21 1983. Online sources include Julian Gollop’s X-COM postmortem from the 2013 Game Developers Conference, “The Story of X-COM” at EuroGamer, and David Jenkins’s interview with Julian Gollop at Metro.

The original X-COM is available for digital purchase at GOG.com, as are most of the other X-COM games mentioned in this article.)