When the lads at DMA Design started making the original Lemmings, they envisioned that it would allow you to bestow about twenty different “skills” upon your charges. But as they continued working on the game, they threw more and more of the skills out, both to make the programming task simpler and to make the final product more playable. They finally ended up with just eight skills, the perfect number to neatly line up as buttons along the bottom of the screen. In the process of this ruthless culling, Lemmings became a classic study in doing more with less in game design: those eight skills, combined in all sorts of unexpected ways, were enough to take the player through 120 ever-more-challenging levels in the first Lemmings, then 100 more in the admittedly less satisfying pseudo-sequel/expansion pack Oh No! More Lemmings.

Yet when the time came to make the first full-fledged sequel, DMA resurrected some of their discarded skills. And then they added many, many more of them: Lemmings 2: The Tribes wound up with no less than 52 skills in all. For this reason not least, it’s often given short shrift by critics, who compare its baggy maximalism unfavorably with the first game’s elegant minimalism. To my mind, though, Lemmings 2 is almost a Platonic ideal of a sequel, building upon the genius of the original game in a way that’s truly challenging and gratifying to veterans. Granted, it isn’t the place you should start; by all means, begin with the classic original. When you’ve made it through those 120 levels, however, you’ll find 120 more here that are just as perplexing, frustrating, and delightful — and with even more variety to boot, courtesy of all those new skills.

The DMA Design that made Lemmings 2 was a changed entity in some ways. The company had grown in the wake of the first game’s enormous worldwide success, such that they had been forced to move out of their cozy digs above a baby store in the modest downtown of Dundee, Scotland, and into a more anonymous office in a business park on the outskirts of town. The core group that had created the first Lemmings — designer, programmer, and DMA founder David Jones; artists and level designers Mike Dailly and Gary Timmons; programmer and level designer Russell Kay — all remained on the job, but they were now joined by an additional troupe of talented newcomers.

Lemmings 2 also reflects changing times inside the games industry in ways that go beyond the size of its development team. Instead of 120 unrelated levels, there’s now a modicum of story holding things together. A lengthy introductory movie — which, in another telling sign of the times, fills more disk space than the game itself and required almost as many people to make — tells how the lemmings were separated into twelve tribes, all isolated from one another, at some point in the distant past. Now, the island (continent?) on which they live is facing an encroaching Darkness which will end all life there. Your task is to reunite the tribes, by guiding each of them through ten levels to reach the center of the island. Once all of the tribes have gathered there, they can reassemble a magical talisman, of which each tribe conveniently has one piece, and use it to summon a flying ark that will whisk them all to safety.

It’s not exactly an air-tight plot, but no matter; you’ll forget about it anyway as soon as the actual game begins. What’s really important are the other advantages of having twelve discrete progressions of ten levels instead of a single linear progression of 120. You can, you see, jump around among all these tribes at will. As David Jones said at the time of the game’s release, “We want to get away from ‘you complete a level or you don’t.'” When you get frustrated banging your head against a single stubborn level — and, this being a Lemmings game, you will get frustrated — you can just go work on another one for a while.

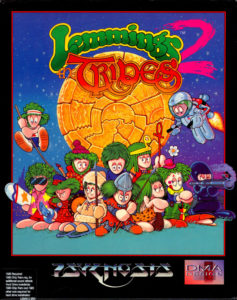

Rather than relying largely on the same set of graphics over the course of its levels, as the original does, each tribe in Lemmings 2 has its own audiovisual theme: there are beach-bum lemmings, Medieval lemmings, spooky lemmings, circus lemmings, alpine lemmings, astronaut lemmings, etc. In a tribute to the place where the game was born, there are even Scottish Highland lemmings (although Dundee is actually found in the less culturally distinctive — or culturally clichéd — Lowlands). And there’s even a “classic” tribe that reuses the original graphics; pulling it up feels a bit like coming home from an around-the-world tour.

Teaching Old Lemmings New Tricks

In this Medieval level, one lemming has become an “attractor”: a minstrel who entrances all the lemmings around him with his music, keeping them from marching onward. Meanwhile one of his colleagues is blazing a trail in front for the rest to eventually follow.

In this Shadow level, the lemming in front has become a “Fencer.” This allows him to dig out a path in front of himself at a slight upward angle. (Most of the skills in the game that at first seem bewilderingly esoteric actually do have fairly simple effects.)

In this Circus level, one lemming has become a “rock climber”: a sort of super-powered version of an ordinary climber, who can climb even a canted wall like this one.

In this Polar level, a lemming has become a “roper,” making a handy tightrope up and over the tree blocking the path.

Other pieces of plumbing help to make Lemmings 2 feel like a real, holistic game rather than a mere series of puzzles. The first game, as you may recall, gives you an arbitrary number of lemmings which begin each level and an arbitrary subset of them which must survive it; this latter number thus marks the difference between success and failure. In the sequel, though, each tribe starts its first level with 60 lemmings, who are carried over through all of the levels that follow. Any lemmings lost on one level, in other words, don’t come back in the succeeding ones. It’s possible to limp to the final finish line with just one solitary survivor remaining — and, indeed, you quite probably will do exactly this with a few of the tribes the first time through. But it’s also possible to finish all but a few of the levels without killing any lemmings at all. At the end of each level and then again at the end of each tribe’s collection of levels, you’re awarded a bronze, silver, or gold star based on your performance. To wind up with gold at the end, you usually need to have kept every single one of the little fellows alive through all ten levels. There’s a certain thematic advantage in this: people often note how the hyper-cute original Lemmings is really one of the most violent videogames ever, requiring you to kill thousands and thousands of the cuties over its course. This objection no longer applies to Lemmings 2. But more importantly, it sets up an obsessive-compulsive-perfectionist loop. First you’ll just want to get through the levels — but then all those bronze and silver performances lurking in your past will start to grate, and pretty soon you’ll be trying to figure out how to do each level just that little bit more efficiently. The ultimate Lemmings 2 achievement, needless to say, is to collect gold stars across the board.

This tiered approach to success and failure might be seen as evidence of a kinder design sensibility, but in most other respects just the opposite is true; Lemmings 2 has the definite feel of a game for the hardcore. The first Lemmings does a remarkably good job of teaching you how to play it interactively over the course of its first twenty levels or so, introducing you one by one to each of its skills along with its potential uses and limitations. There’s nothing remotely comparable in Lemmings 2; it just throws you in at the deep end. While there is a gradual progression in difficulty within each tribe’s levels, the game as a whole is a lumpier affair, especially in the beginning. Each level gives you access to between one and eight of the 52 available skills, whilst evincing no interest whatsoever in showing you how to use any of them. There is some degree of thematic grouping when it comes to the skills: the Highland lemmings like to toss cabers; the beach lemmings are fond of swimming, kayaking, and surfing; the alpine lemmings often need to ski or skate. Nevertheless, the sheer number of new skills you’re expected to learn on the fly is intimidating even for a veteran of the first game. The closest Lemmings 2 comes to its predecessor’s training levels are a few free-form sandbox environments where you can choose your own palette of skills and have at it. But even here, your education can be a challenging one, coming down as it still does to trial and error.

Your first hours with the game can be particularly intimidating; as soon as you’ve learned how one group of skills works well enough to finish one level, you’re confronted with a whole new palette of them on the next level. Even I, a huge fan of the first game, bounced off the second one quite a few times before I buckled down, started figuring out the skills, and, some time thereafter, started having fun.

Luckily, once you have put in the time to learn how the skills work, Lemmings 2 becomes very fun indeed, — every bit as rewarding as the first game, possibly even more so. Certainly its level design is every bit as good — better in fact, relying more on logic and less on dodgy edge cases in the game engine than do the infamously difficult final levels of the first Lemmings. Even the spiky difficulty curve isn’t all bad; it can be oddly soothing to start on a new tribe’s relatively straightforward early levels after being taxed to the upmost on another tribe’s last level. If the first Lemmings is mountain climbing as people imagine it to be — a single relentless, ever-steeper ascent to a dizzying peak — the second Lemmings has more in common with the reality of the sport: a set of more or less difficult stages separated by more or less comfortable base camps. While it’s at least as daunting in the end, it does offer more ebbs and flows along the way.

One might say, then, that Lemmings 2 is designed around a rather literal interpretation of the concept of a sequel. That is to say, it assumes that you’ve played its predecessor before you get to it, and are now ready for its added complexity. That’s bracing for anyone who fulfills that criterion. But in 1993, the year of Lemmings 2‘s release, its design philosophy had more negative than positive consequences for its own commercial arc and for that of the franchise to which it belonged.

The fact is that Lemmings 2‘s attitude toward its sequel status was out of joint with the way sequels had generally come to function by 1993. In a fast-changing industry that was fast attracting new players, the ideal sequel, at least in the eyes of most industry executives, was a game equally welcoming to both neophytes and veterans. Audiovisual standards were changing so rapidly that a game that was just a couple of years old could already look painfully dated. What new player with a shiny new computer wanted to play some ugly old thing just to earn a right to play the latest and greatest?

That said, Lemmings 2 actually didn’t look all that much better than its predecessor either, flashy opening movie aside. Part of this was down to DMA Design still using the 1985-vintage Commodore Amiga, which was still very popular as a gaming computer in Britain and other European countries, as their primary development platform, then porting the game to MS-DOS and various other more modern platforms. Staying loyal to the Amiga meant working within some fairly harsh restrictions, such as that of having no more than 32 colors on the screen at once, not to mention making the whole game compact enough to run entirely off floppy disk; hard drives, much less CD-ROM drives, were still not common among European Amiga owners. Shortly before the release of Lemmings 2, David Jones confessed to being “a little worried” about whether people would be willing to look beyond the unimpressive graphics and appreciate the innovations of the game itself. As it happened, he was right to be worried.

Lemmings and Oh No! More Lemmings sold in the millions across a bewildering range of platforms, from modern mainstream computers like the Apple Macintosh and Wintel machines to antique 8-bit computers like the Commodore 64 and Sinclair Spectrum, from handheld systems like the Nintendo Game Boy and Atari Lynx to living-room game consoles like the Sega Master System and the Nintendo Entertainment System. Lemmings 2, being a much more complex game under the hood as well as on the surface, wasn’t quite so amenable to being ported to just about any gadget with a CPU, even as its more off-putting initial character and its lack of new audiovisual flash did it no favors either. It was still widely ported and still became a solid success by any reasonable standard, mind you, but likely sold in the hundreds of thousands rather than the millions. All indications are that the first game and its semi-expansion pack continued to sell more copies than the second even after the latter’s release.

In the aftermath of this muted reception, the bloom slowly fell off the Lemmings rose, not only for the general public but also for DMA Design themselves. The franchise’s true jump-the-shark moment ironically came as part of an attempt to re-jigger the creatures to become media superstars beyond the realm of games. The Children’s Television Workshop, the creator of Sesame Street among other properties, was interested in moving the franchise onto television screens. In the course of these negotiations, they asked DMA to give the lemmings more differentiated personalities in the next game, to turn them from anonymous marchers, each just a few pixels across, into something more akin to individualized cartoon characters. Soon the next game was being envisioned as the first of a linked series of no less than four of them, each one detailing the further adventures of three of the tribes after their escape from the island at the end of Lemmings 2, each one ripe for trans-media adaptation by the Children’s Television Workshop. But the first game of this new generation, called The Lemmings Chronicles, just didn’t work. The attempt to cartoonify the franchise was cloying and clumsy, and the gameplay fell to pieces; unlike Lemmings 2, Lemmings Chronicles eminently deserves its underwhelming critical reputation. DMA insiders like Mike Dailly have since admitted that its was developed more out of obligation than enthusiasm: “We were all ready to move on.” When it performed even worse than its predecessor, the Children’s Television Workshop dropped out; all of its compromises had been for nothing.

Released just a year after Lemmings 2, Lemmings Chronicles marked the last game in the six-game contract that DMA Design had signed with their publisher Psygnosis what seemed like an eternity ago — in late 1987 to be more specific, when David Jones had first come to Psygnosis with his rather generic outer-space shoot-em-up Menace, giving no sign that he was capable of something as ingenious as Lemmings. Now, having well and truly demonstrated their ingenuity, DMA had little interest in re-upping; they were even willing to leave behind all of their intellectual property, which the contract Jones had signed gave to Psygnosis in perpetuity. In fact, they were more than ready to leave behind the cute-and-cuddly cartoon aesthetic of Lemmings and return to more laddish forms of gaming. The eventual result of that desire would be a second, more long-lasting worldwide phenomenon, known as Grand Theft Auto.

Meanwhile Sony, who had acquired Psygnosis in 1993, continued off and on to test the waters with new iterations of the franchise, but all of those attempts evinced the same vague sense of ennui that had doomed Lemmings Chronicles; none became hits. The last Lemmings game that wasn’t a remake appeared in 2000.

It’s interesting to ask whether DMA Design and Psygnosis could have managed the franchise better, thereby turning it into a permanent rather than a momentary icon of gaming, perhaps even one on a par with the likes of Super Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog; they certainly had the sales to compete head-to-head with those other videogame icons for a few years there in the early 1990s. The obvious objection is that Mario and Sonic were individualized characters, while DMA’s lemmings were little more than a handful of tropes moving in literal lockstep. Still, more has been done with less in the annals of media history. If everyone had approached Lemmings Chronicles with more enthusiasm and a modicum more writing and branding talent, maybe the story would have turned out differently.

Many speculate today that the franchise must inevitably see another revival at some point, what with 21st-century pop culture’s tendency to mine not just the A-list properties of the past, but increasingly its B- and C-listers as well, in the name of one generation’s nostalgia and another’s insatiable appetite for kitsch. Something tells me as well that we haven’t seen the last of Lemmings, but, as of this writing anyway, the revival still hasn’t arrived.

As matters currently stand, then, the brief-lived but frenzied craze for Lemmings has gone down in history, alongside contemporaries like Tetris and The Incredible Machine, as one more precursor of the casual revolution in gaming that was still to come, with its very different demographics and aesthetics. But in addition to that, it gave us two games that are brilliant in their own right, that remain as vexing but oh-so-rewarding as they were in their heyday. Long may they march on.

One other surviving tribute to Dundee’s second most successful gaming franchise is this little monument at the entrance to the city’s Seabraes Park, erected by local artist Alyson Conway in 2013. Lemmings and Grand Theft Auto… not bad for a city of only 150,000 souls.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene; Compute! of January 1992; Amiga Format of May 1993 and the special 1992 annual; Retro Gamer 39; The One of November 1993; Computer Gaming World of July 1993.

Lemmings 2 has never gotten a digital re-release. I therefore make it available for download here, packaged to be as easy as possible to get running under DOSBox on your modern computer.)