In September of 1991, Bob Bates of Legend Entertainment flew to Florida for a meeting of the Software Publishers Association. One evening there after a long day on the job, still dressed in his business suit, he took a walk along the beach, enjoying a gorgeous sunset as he anticipated a relaxing dinner with his wife and infant son, who had joined him on the trip.

Yet his mind wasn’t quite as peaceful as was the scenery around him. He was in fact wrestling with a tension which everybody who does creative work for a living must face at some point: the tension between what the artist wants to create and what the audience wants to buy. Bob had made Timequest, his first game after co-founding Legend, as a self-conscious experiment, meant to determine whether a complicated, intricate, serious, difficult parser-driven adventure game was still a commercially viable proposition in 1991. The answer was, as Bob puts it today, “kind of”: Timequest hadn’t flopped utterly, but it hadn’t sold in notably big numbers either. Steve Meretzky’s decidedly lower-brow games Spellcasting 101 and 201, which had bookended Timequest on Legend’s release schedule, had both done considerably better. Bob had already started making notes for a Timequest II by the time the first one shipped, but he soon had to face the reality that the sales numbers just weren’t there to support more iterations on the concept.

Now, in the midst of his walk on the beach, a name sprang unbidden into his head: “Eric the Unready.” Such a gift from God — or from his subconscious — had never come to him before in that manner, and never would again. But no matter; once in a lifetime ought to be enough for anyone. He found the name hilarious, and chuckled to himself over it the rest of the way to the restaurant. At last, he knew what his next game would be: a straight-up farce about a really, really unready knight named Eric. With that decision made, he was ready to enjoy his evening.

The more he thought about the idea upon returning to daily life inside Legend’s Virginia offices, the more he realized that it had more going for it in practical terms than most rarefied bolts from the blue can boast. Indeed, it was an idea about which no marketer could possibly have complained, being well-nigh precision-targeted to hit the industry’s commercial sweet spot as accurately as any Legend title could hope to. If the success of Legend’s Spellcasting games hadn’t sufficiently proved to the company how potent a combination comedy and fantasy could be, there was plenty of other evidence on offer. Adventure gamers loved comedy, which was just as well given that it was the default setting the form always wanted to collapse back into, a gravitational attraction that could be defied by a designer only through serious, single-minded effort; these realities explained why Sierra made so many comedies, and why LucasArts’s adventure catalog contained very little else. And gamers in general just couldn’t get enough fantasy; this explained the quantity of dungeon-crawling CRPGs clogging store shelves, not to mention the success of Sierra’s King’s Quest adventure series. To complete the formula for sales gold, Bob soon decided that Eric the Unready would also toss aside all of Timequest‘s puzzle complexity to jump onto what Legend saw as another emerging industry trend: that of making adventure games friendlier, more accessible to the non-hardcore. In short, Bob’s latest game would be easy.

So, Eric the Unready was to be an unabashed bid for mainstream success, as safe a play as Legend knew how to make at this juncture. But such a practical commercial profile isn’t necessarily an artistic kiss of death; like all of the best of such efforts, Eric the Unready is executed with such panache that even a jaded old critic like me just can’t help but love it in spite of his snobbishness.

Inveterate student of history that he is, Bob’s first impulse upon starting any project is always to head to the library. In fact, one might say that his research for Eric the Unready began long before he even thought to make the game. The name itself actually has an historical antecedent, one which was doubtless bouncing around somewhere in the back of Bob’s mind when he had his brainstorm: Æthelred the Unready is the name of an English king from shortly before the Norman Conquest. The epithet had always amused Bob inordinately. (For the record: the word “unready” in this context means something closer to poorly advised than personally incompetent. Nevertheless, it was the latter, anachronistic meaning which Bob was about to embrace with glee.)

After the project began in earnest, Bob’s research instinct meant lots of reading of contemporary fantasy, a genre he had heretofore known little about. More out of a sense of duty than enthusiasm, he worked through Margaret Weis and Tracey Hickman’s Dragonlance and Death Gate novels, Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga, and even Stephen R. Donaldson’s terminally turgid Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever.

In the end, none of it would prove to have been necessary — and this was all for the best. Eric the Unready has little beyond its “fantasy” label in common with such po-faced epics. The milieu of the finished game is vaguely Arthurian, as you might expect of a game written by the Anglophile creator of Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur. This time out, though, Bob tempered his interest in Arthurian myth with a willingness to toss setting and even plot coherence overboard at any time in the name of a good joke. As such, the game inevitably brings to mind a certain Monty Python movie — and, indeed, there is much of that beloved British comedy troupe in the game. Other strong influences which Bob himself names include Douglas Adams, Terry Pratchett, and, hitting closer to home, Steve Meretzky.

The humor of Eric the Unready might best be summarized as “maximalism with economy.” Bob:

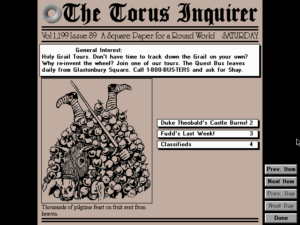

My [plots] were always meant to be scrupulously well-designed,. There was never a logical inconsistency. All of them were solidly constructed. But with Eric the Unready, I consciously said, “If I see the opportunity for a joke that doesn’t quite make sense, I’m going to do it anyway.” Toward the end of the project, I wondered how many jokes there were in Eric. I can remember counting that there were over a thousand of them. It’s just crammed full of funny material: in the newspapers, hidden in the conversations, hidden all over the place.

The economy comes in, however, with Eric the Unready‘s determination never to beat any single joke into the ground — something that even Steve Meretzky was prone to do in too much of his post-Infocom work. As Graham Nelson and others have pointed out, one of Infocom’s secret weapons was, paradoxical though it may sound, the very limitations of their Z-Machine. The sharply limited quantity of text it allowed, combined with the editorial oversight of Jon Palace, Infocom’s unsung hero, kept their writers from rambling on and on. But text had become cheap on the computers of the 1990s, and thus Legend’s software technology, unlike Infocom’s, allowed the author an effectively unlimited number of words — a dangerous thing for any writer. A Legend author was under no compulsion whatsoever to edit himself.

Luckily, Bob Bates’s dedication to doing the research came through for him here, in a way that ultimately proved far more valuable than his study of fantasy fiction. He had been interested in the mechanics and theory of comedy long before starting on the game, and now reread what some of the past masters of the form — people like Milton Berle and Johnny Carson — had to say about it. He recalled an old anecdote from the latter, which he paraphrases as, “Not everybody is going to like every joke. But if you can get 60 percent of the people to laugh at 60 percent of your jokes, you’re a success.” One of the funniest writers ever once noted in the same spirit that “brevity is the soul of wit.” Combining these two ideals, Bob’s approach to the humor in Eric the Unready became not to stress over or belabor anything. He would crack a joke, then be done with it and move on to the next one; rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. “There’s always another bus coming,” says Bob by way of summing up his comedy philosophy. “If you don’t get this one, don’t worry; you’ll get the next one.”

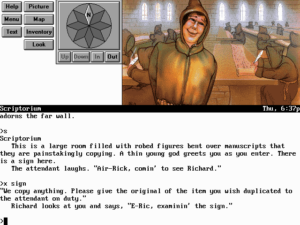

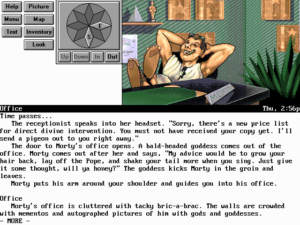

At this point, then, I’d like to share some of Eric the Unready‘s greatest comedic hits with you. One of the pleasures for me in revisiting this game a quarter-century on has been remembering all of the contemporary pop culture it references, pays homage to, or (more commonly) skewers. Thus many of the screenshots you see below are of that sort — wonderful for remembering the somehow more innocent media landscape of the United States during the immediate post-Cold War era, that window of peace and prosperity before history caught up with us again on September 11, 2001. (Why does the past always strike us as more innocent? Is it because we know what will come after, and familiarity breeds quaintness?)

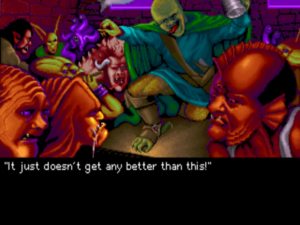

But another of my agendas is to commemorate Legend’s talented freelance art team, whose work was consistently much better than we had any right to expect from such a small studio. Being a writer myself, I have a tendency to emphasize writing and design while giving short shrift to the visual aesthetics of game-making. So, let me remedy that for today at least. The quality of the artwork below is largely thanks to Tanya Isaacson and Paul Mock, Legend’s two most important artists, who placed their stamp prominently on everything that came out of the company during this period.

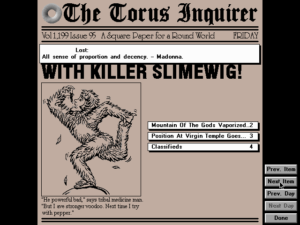

Each chapter includes a copy of the newspaper for that day. Together, they provide a running commentary on Eric’s misadventures of the previous chapters — and lots of opportunities for more jokes. Shay Addams, the publisher of the Questbusters newsletter and book series and a ubiquitous magazine commentator and reviewer, rivaled Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia for the title of most prominent of all the American adventure-game superfans who parleyed their hobbies into paychecks. (Scorpia as well showed up in games from time to time — perhaps most notably, as a poisonous monster in New World Computing’s Might and Magic III, her comeuppance for a negative review of Might and Magic II.) Alas, Addams disappeared without a trace about a year after Eric the Unready was published. Rumor had it that he took up a career as a professional gambler (!) instead.

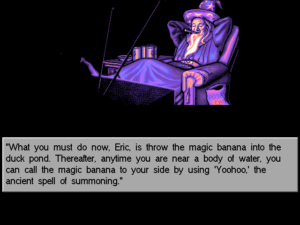

A really old-school shout-out, to Scott Adams, the first person to put a text adventure on a microcomputer. “Yoho” was a magic word in his second and most popular game of all, Pirate Adventure.

The computer-game industry of the early 1990s still had some of the flavor of pre-Hays Code Hollywood. Even as parents and politicians were fretting endlessly over what Super Mario Bros. was doing to Generation Nintendo, computer games remained off their radar entirely. That would soon change, however, bringing with it the industry’s first attempts at content rating and self-censorship.

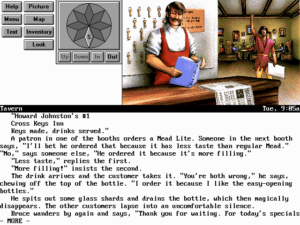

The “tastes great, less filling” commercials for Miller Lite were an inescapable presence on American television for almost two decades, placing athletes and B-list celebrities in ever more elaborate beer-drinking scenarios which always concluded with the same tagline. They still serve as a classic case study in marketing for the way they convinced stereotypically manly, sports-loving male beer drinkers that it was okay to drink a (gasp!) light beer.

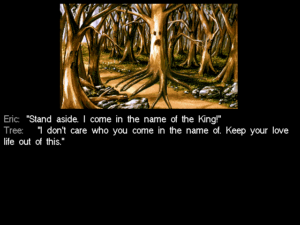

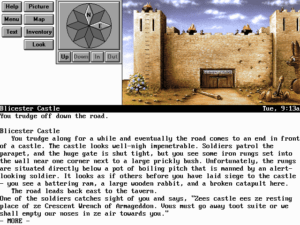

We couldn’t possibly skip an explicit homage to Monty Python and the Holy Grail, could we?

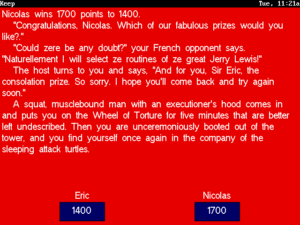

Wheel of Fortune — and the bizarre French obsession with Jerry Lewis.

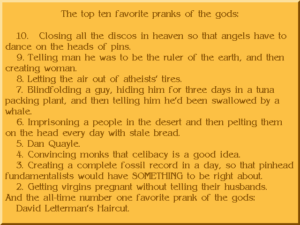

David Letterman’s top-ten lists were a pop-culture institution for almost 35 years. Note the presence on this one of Vice President Dan Quayle, who once said that Mars had air and canals filled with water, and once lost a spelling bee to a twelve-year-old by misspelling “potato.”

Rob Schneider’s copy-machine guy was one of the more annoying Saturday Night Live characters to become an icon of his age…

Speaking of Saturday Night Live: in one of the strangest moments in the history of the show, the Irish singer Sinead O’Connor belted out a well-intentioned but ham-fisted a-capella scold against human-rights abuse in lieu of one of her radio hits. At the end of the song, she tore up a picture of the pope as a statement against the epidemic of child molestation and abuse in the Catholic Church.

Some of Miller Lite’s competition in terms of iconic beer commercials for manly men came in the form of Old Milwaukee and its “It just doesn’t get any better than this” tagline. (Full disclosure: Old Milwaukee was my dad’s brew of choice, I think mostly because it was just about the cheapest beer you could buy. I have memories of watching John Wayne movies on his knee, coveting the occasional sip of it I was vouchsafed.)

Madonna was at her most transgressive during this period: she had just released an album entitled Erotica and a coffee-table book of softcore porn entitled simply Sex. Looked back on today, her desperate need to shock seems more silly than threatening, but people reacted at the time as if the world was ending. (I should know; I was working at a record store when the album came out. Ah, well… even as an indie-rock snob, I had to recognize that her version of “Fever” slays.) Meanwhile the picture that accompanies the newspaper article above pays tribute to another pop diva: Grace Jones.

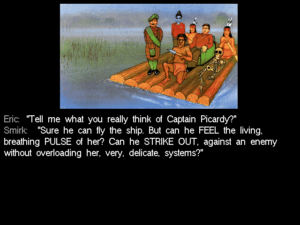

My favorite chapter has you exploring a “galaxy” of yet more pop-culture detritus with the unforgettable Captain Smirk, described as “250 pounds of captain stuffed into a 175-pound-captain’s shirt.” (This joke might just be my favorite in the whole game…)

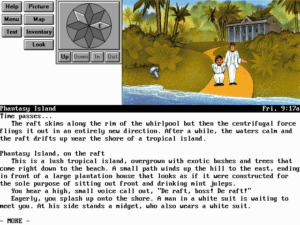

Fantasy Island, in which a new collection of recognizable faces was gathered together each week to live out their deepest desires and learn some life lessons in the process, was one of the biggest television shows of the pop-culture era just before Eric the Unready, when such aspirational lifestyle fare set in exotic locations — see also Fantasy Island‘s more family-friendly sibling The Love Boat — was all the rage. It all really does feel oddly quaint and innocent today, doesn’t it?

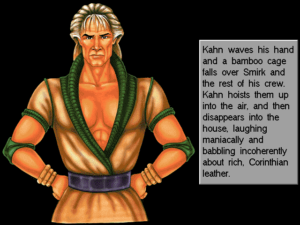

Eric the Unready manages to combine all three of actor and decadent lifestyle icon Ricardo Montalbán’s most recognizable personas in one: as Mr. Roarke of Fantasy Island, as Khan of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and as a pitchman for Chrysler.

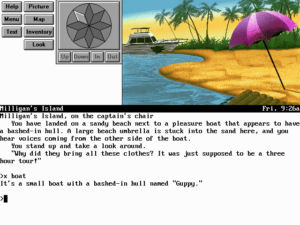

And at last we come to Gilligan’s Island, a place within a three-hour sailing tour of civilization which has nevertheless remained uncharted — the perfect scene for a sitcom as breathtakingly stupid as its backstory.

Eric the Unready is the first Legend game to fully embrace the LucasArts design methodology of no player deaths and no dead ends. Even if you deliberately try to throw away or destroy essential objects out of curiosity or sheer perversity, the game simply won’t let you; the object in question is always restored to you, often by means that are quite amusing in themselves. Just as in a LucasArts comedy, the sense of freedom this complete absence of danger provides often serves the game well, empowering you to try all sorts of crazy and funny things without having to worry that doing so will mean a trip back to your collection of save files. Unlike many LucasArts games, though, Eric the Unready doesn’t even try all that hard to find ways of presenting truly intriguing puzzles that work within its set of player guardrails. In fact, if there’s a problem with Eric the Unready, it must be that the game offers so little challenge; Bob Bates’s determination to make it the polar opposite of Timequest in this respect carried all the way through the project.

The game is really eight discrete mini-games. At the start of each of these “chapters,” Eric is dumped into a new, self-contained environment that exists independently of what came before or what will come later. By limiting the combinatorial-explosion factor, this structure makes both the designer’s and the player’s job much easier. Even within a chapter, however, there are precious few head-scratching moments. You’re told what you need to do quite explicitly, and then you proceed to do it in an equally straightforward manner — and that’s pretty much all there is to solving the game. Bob long considered it to be the easiest game by far he had ever designed. (He was, he noted wryly when I spoke to him recently, forced by popular demand to make his recent text adventure Thaumistry even easier, which serves as something of a commentary on the ways in which player expectations have changed over the past quarter-century.)

All that said, it should also be noted that Eric the Unready‘s disinterest in challenging its player was more of a problem at the time of its original release than it is today. Whatever their other justifications, difficult puzzles served as a way of gumming up the works for the player back in the day, keeping her from burning through a game’s content too quickly at a time when the average game’s price tag in relation to its raw quantity of content was vastly higher than today. Without challenging puzzles, a player could easily finish a game like Eric the Unready in less than five hours, in spite of its having several times the amount of text of the average Infocom game (not to mention the addition of graphics, music, and sound effects). At a retail price of $35 or $40, this was a real issue. Today, when the game sells as a digital download for a small fraction of that price, it’s much less of one. Modern distribution choices, one might say, have finally allowed Eric the Unready to be exactly the experience it wants to be without apologies.

Certainly Bob has fantastically good memories of making this game; he still calls it the most purely enjoyable creative endeavor of his life. Those positive vibes positively ooze out of the finished product. Yet there was a shadow lurking behind all of Bob’s joy, lending it perhaps an extra note of piquancy. For he knew fairly early in Eric the Unready‘s development cycle that this would be the last game of this type he would get to design for the foreseeable future. Legend, you see, was on the verge of dumping the parser at last.

They had fought the good fight far longer than any of their peers. By the time Eric the Unready shipped in January of 1993, Legend had been the only remaining maker of parser-based adventure games for the mainstream, boxed American market for over two years. As part of their process of bargaining with marketplace realities, they had done everything they could think of to accommodate the huge number of gamers who regarded the likes of an Infocom game much as the average contemporary movie-goer regarded a Charlie Chaplin film. In a bid to broaden their customers demographic beyond the Infocom diehards, Legend from the start had added an admittedly clunky method of building sentences by mousing through long menus of verbs, nouns, and prepositions, along with copious multimedia gilding around the core text-adventure experience.

As budgets increased and the market grew still more demanding, Legend came to lean ever more heavily on both the mouse and their multimedia bells and whistles. By the time they got to Eric the Unready, their games were already starting to feel as much point-and-click as not, as the regular text-and-parser window got superseded for long stretches of time by animated cut scenes, by full-screen static illustrations, by mouseable onscreen documents, by mouse-driven visual puzzles. Even when the parser interface was on display, you could now choose to click on the onscreen illustrations of the scenes themselves instead of the words representing the things in them if you so chose.

Still, it was obvious that even an intermittent recourse to the parser just wouldn’t be tenable for much longer. In this new era of consumer computing, a command line had become for many or most computer users that inscrutable, existentially terrifying thing you got dumped into when something broke down in your Windows. The last place these people wanted to see such a thing was inside one of their games. And so the next step — that of dumping the parser entirely — was as logical as it was inevitable.

Eric the Unready wouldn’t quite be the absolute last of its breed — Legend’s Gateway 2: Homeworld would ship a few months after it — but it was the very last of Bob’s children of the type. Once Eric the Unready and Gateway 2 shipped, an era in gaming history came to an end. The movement that had begun when Scott Adams shipped the first copies of Adventureland on hand-dubbed cassette tapes for the Radio Shack TRS-80 in 1978 had run its course. Yes, there was a world of difference between Adams’s 16 K efforts with their two-word parsers and pidgin English and the tens of megabytes of multimedia splendor of an Eric the Unready or a Gateway 2, but they were all nevertheless members of the same basic gaming taxonomy. Now, though, no more games like them would ever appear again on the shelves of everyday software stores.

And make no mistake: something important — precious? — got lost when Legend finally dumped the parser entirely. Bob felt the loss as keenly as anyone; through all of his years in games which would follow, he would never entirely stop regretting it. Bob:

What you’re losing [in a point-and-click interface] is the sense of infinite possibility. There may still be a sense that there’s lots you can do, and you can still have puzzles and non-obvious interactions, but you’ve lost the ability to type anything you want. And it was a terrible thing to lose — but that’s the way the world was going.

I found the transition personally painful. That’s evidenced by the fact that I went back and wrote another parser-based game more than twenty years later. A large part of the joy of making this type of game for me is the sense that I’m the little guy in the box. It’s me and the player. The player senses my presence and feels like we’re engaged in this activity together. There’s a back-and-forthing — communication — between the two of us. It’s obviously all done on my part ahead of time, but the player should feel like there’s somebody behind the curtain, that it’s a live exchange. It should feel like somebody is responding as an individual to the player.

As Bob says, point-and-click games are … not necessarily worse, but definitely different. The personal connection with the designer is lost.

A long time ago now in what feels like another life, I entitled the first lengthy piece I ever wrote about interactive fiction “Let’s Tell a Story Together.” At its best, playing a text adventure really can feel like spending time one-on-one with a witty narrator, raconteur, and intellectual sparring partner. I would even go so far as to admit that text adventures have cured me of loneliness once or twice in my life. There’s nothing else in games comparable to this experience; only a great book might possibly compare, but even it lacks the secret sauce of interactivity. Indeed, text adventures may be the only truly literary form of computer game. Just as a book is the most personal, intimate form of traditional artistic expression, so is a text adventure its equivalent in interactive terms.

Granted, some of those qualities may initially be obscured in Eric the Unready by all the flash surrounding the command prompt. But embrace the universe of possibilities that are still offered up by that blinking cursor, sitting there asking you to try absolutely anything you wish to, and you’ll find that the spirit which changed the lives of so many of us when we encountered our first Infocom game lives on even here. Don’t just rush through the fairly trivial task of solving this game; try stuff, just to see what the little man behind the curtain says back. Trust me when I say that he’s very good company. One can only hope that all of those who bought Eric the Unready in 1993 appreciated him while he was still around.

(My huge thanks go to Bob Bates for setting aside yet another few hours to talk about the life and times of Legend circa 1992 to 1993.

Eric the Unready can be purchased on GOG.com. It’s well worth the money.)