Frederik Pohl, who died on September 2, 2013, at age 93, had one of the most multifaceted careers in the history of written science fiction. Almost uniquely, he played major roles in all three of the estates that constitute science fiction’s culture: the first estate of the creators, in which he wrote stories and novels over a span of many decades; the second estate of the publishers and other business interests, in which he served as a highly respected and influential agent, editor, and anthologist over a similar period of time; and the third estate of fandom, in which his was an important voice from the very dawn of the pulp era, and for which he never lost his enthusiasm, attending science-fiction conventions and casting his votes on fan committees right up to the end.

Growing up between the world wars in Brooklyn, New York, Pohl discovered the nascent literary genre of science fiction in 1930 at the age of 10, when he stumbled upon an issue of Science Wonder Stories. From that moment on, he spent his time at every opportunity with the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Princess of Mars and Doc Smith’s Lensmen — catnip for any red-blooded young boy with any sense of wonder at all. In comparison to other young science-fiction fanatics, however, Pohl stood out for his personableness, his ambition, his spirit of innovation, and his sheer commitment to the things he loved. He became a founding member of the Brooklyn Science Fiction League, one of the earliest instances of organized science-fiction fandom anywhere in the country, and by the ripe old age of 13 or so had become a prolific editor and publisher of fanzines, many of which enjoyed a total circulation reaching all the way into two figures.

The world of science fiction was indeed still a small one, but that had its advantages in terms of access, especially when one was fortunate enough to live in the pulp publishing capital that was New York City. The boundaries between science-fiction fan and the “profession” of science-fiction writer were porous, and by the latter half of the 1930s Pohl was hobnobbing with such luminaries as Isaac Asimov and Cyril Kornbluth in an informal club of like-minded souls who called themselves the Futurians. He stumbled into the job of acting as the Futurians’ literary agent, which entailed buying stamps and envelopes in bulk, mailing off his friends’ stories to every pulp publisher in the Big Apple, and collecting lots of rejection slips alongside the occasional letter of acceptance in the return post.

In 1939, a 19-year-old Frederik Pohl got himself an editor’s job at the pulp house Popular Publications by virtue of knocking on their door and asking for one. He was given responsibility for Astonishing and Super Science Stories, second-tier magazines that paid their writers a penny per word and trafficked in the stories that weren’t good enough for John W. Campbell’s Astounding, the class of the field. Most of the authors whose stories Pohl accepted are justifiably forgotten today, but he did get his hands every now and then on a sub-par offering from the likes of a Robert A. Heinlein or L. Sprague de Camp that Campbell had rejected; Pohl, alas, was in no position to be so choosy.

But then along came the Second World War to put everything on hold for a while. Pohl wound up joining the Army Air Force, and was rewarded with what he freely described as a “cushy” war experience, working as meteorologist for a B-24 squadron based in Italy. When he returned from Europe, he returned to publishing as well but, initially, not to science fiction. Now a married man with familial responsibilities, he worked for a few years as an advertising copywriter, then as an editor for the book adjuncts to the magazines Popular Science and Outdoor Life; this constitutes the only substantial period of his entire professional life spent outside science fiction.

Yet the pull of science fiction remained strong, and in the early 1950s Pohl resumed his old role of literary agent for his writer buddies, albeit now on a slightly more professional footing. The locus of science-fiction profits was moving from the pulps to paperback novels and short-story collections in book form; thus Pohl became an editor for Ballantine’s new line of science-fiction paperbacks. By this point, the name of Frederik Pohl, while still fairly obscure to most readers, was known to everyone inside the community of science-fiction writers. He really was on a first-name basis with everyone who was anyone in the field, from hard science fiction’s holy trinity of Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke to lyrical science fiction’s patron saint Ray Bradbury.

In 1960, a 41-year-old Pohl accepted what was destined to become his most influential behind-the-scenes role of all when he agreed to become editor of a troubled ten-year-old also-ran of a magazine called Galaxy Science Fiction. “The pay was miserable,” he would later remember. “The work was never-ending. It was the best job I ever had in my life.”

At that time, science fiction was on the precipice of a new era, as a more culturally, racially, sexually, and stylistically diverse generation of up-and-coming writers — the so-called “New Wave” — began to arrive on the scene with a new interest in prose quality and formal experimentation, alongside an interest in exploring the future in terms of human psychology rather than technology alone. Many or most of the old guard who had cut their teeth in the pulp era, whose politics tended to veer conservative in predictable middle-aged-white-male fashion, greeted this invasion of beatnik radicals with dismay and contempt. The card-carrying John Birch Society member John W. Campbell, who was still editing Astounding — or rather, as it had recently been renamed, Analog Science Fiction — was particularly vocal in his criticism of all this new-fangled nonsense.

Frederik Pohl, however, was different from most of his peers. He had always read widely outside the field of science fiction as well as inside it, and was as comfortable discussing the stylistic experiments of James Joyce and Marcel Proust as he was the clockwork plots of Doc Smith. And as for politics… well, he had spent four years as a card-carrying member of the American Communist Party — take that, John Campbell! — and even after disillusionment with the Soviet Union of Josef Stalin had put an end to that phase he had retained his leftward bent.

In short: Frederik Pohl welcomed the new arrivals and their new ideas with open arms, making Galaxy a haven for works at the cutting edge of modern science fiction, superseding Campbell’s increasingly musty-smelling Analog as the genre’s journal of record. He had to, as he later put it, “encourage, coax, and sometimes browbeat” his charges to get the very best work out of them, but together they changed the face of science fiction. Indeed, it was arguably helping other writers be their best selves that constituted this multifariously talented man’s most remarkable talent of all. Perhaps his most difficult yet rewarding writer was the famously irascible Harlan Ellison, who burst to prominence in the pages of Galaxy and If, its sister publication, with stories whose names were as scintillatingly trippy as their contents: “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,” “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” “The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World.” Such stories were painfully shaped over the course of a series of bloody rows between editor and writer. Most readers would agree that Ellison’s later fiction has never approached the quality of these early stories, churned out under the editorship of Frederik Pohl.

Burned out at last by the job of editing Galaxy, Pohl stepped down at the end of the 1960s, a decade that had transformed the culture of science fiction every bit as much as it had the larger American culture that surrounded it. In the following decade, however, he continued to push the boundaries as an editor for Bantam Books. It was entirely thanks to him that Bantam in 1975 published Samuel R. Delany’s experimental masterpiece or colossal con job — depending on the beholder — Dhalgren, nearly 900 pages of digressive, circular prose heavily influenced by James Joyce’s equally controversial Finnegans Wake. Whatever else you could say about it, science fiction had come a long way from the days of Science Wonder Stories and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

All of which is to say that Frederik Pohl would have made a major impact on the field of science fiction had he never written a word of his own. In actuality, though, he managed to combine all of the work I’ve described to this point with an ebbing and flowing output of original short stories and novels, beginning with, of all things, a rather awkwardly adolescent poem called “Elegy to a Dead Satellite: Luna,” which appeared in Amazing Stories in 1937. Through the ensuing decades, Pohl was regarded as a competent but second-tier writer, the kind who could craft a solid tale but seldom really dazzled. Yet he kept at it; if nothing else, continuing to work as a writer in his own right gave him a feeling for what the more high-profile writers he represented and edited were going through. In 1967, he even switched roles with his frenemy Harlan Ellison by contributing a story to the latter’s Dangerous Visions anthology, a collection of deliberately provocative stories — the sorts of things that could never, ever have gotten into print in earlier years — from New Age writers and adventurous members of the old guard; it went on to become what many critics consider the most important and influential science-fiction anthology of all time.

But even Pohl’s contribution there — “The Day After the Day After the Martians Came,” a parable about the eternal allure of racism and xenophobia that was well-taken then and now but far less provocative than many of the anthology’s other stories — didn’t really change perceptions of him as a fine editor with a sideline in writing rather than the opposite. That shift didn’t happen until a decade later, when the now 58-year-old Pohl published a novel called Gateway. Coming after the most important work of the vast majority of his pulpy peers was well behind them, Pohl’s 21st solely-authored or co-authored novel constitutes the most unlikely story of a late blooming in the history of science fiction.

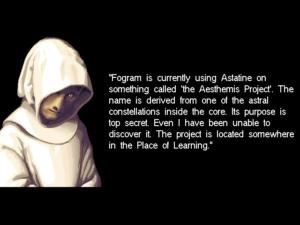

Described in the broadest strokes, Gateway sounds like the sort of rollicking space opera which John W. Campbell would have loved to publish back in the heyday of Astounding. In our solar system’s distant past, when the primitive ancestors of humanity had yet to discover fire, an advanced star-faring race, later to be dubbed the Heechee by humans, visited, only to abandon their bases an unknown period of time later. As humans begin to explore and settle the solar system in our own near future, they discover a deserted Heechee space station in an elliptical orbit around our sun. They find that the station still contains bays full of hundreds of small spaceships, and discover the hard way that, at the press of a mysterious button, these spaceships sweep their occupants away on a non-negotiable faster-than-light journey to some other corner of the galaxy, then (hopefully) back to Earth at the press of another button; for this reason, they name the station Gateway, as in, “Gateway to the Stars.” Many of the destinations the spaceships visit are pointless; some, such as the interior of a black hole, are deadly. Sometimes, though, the spaceships travel to habitable planets and/or to planets containing other artifacts of Heechee technology, worth a pretty penny to scientists, engineers, and collectors back on Earth.

Earth itself is not in very good shape socially, culturally, or environmentally. Overpopulation and runaway capitalism have all but ruined the planet and created an underclass of have-nots who make up the vast majority of the population, working in unappetizing industries like “food shale mines.” The so-called Gateway Corporation, which has taken charge of the station, runs a lottery for people interested in climbing into a Heechee spaceship, pressing a button, and seeing where it takes them. Possibly they can end up rich; more likely, they might wind up dead, their bodies left to decay hundreds of light years from home. But, conditions being what they are among the teeming masses, there’s no shortage of volunteers ready and willing to take such a long shot. These intrepid — or, rather, desperate — explorers are known as the Gateway “prospectors.”

That, then, is the premise — a premise offering a universe of possibility to any writer with an ounce of the old pulpy space-opera spirit. Who are (or were) the Heechee? Why did they disappear? Did they intend for humans to discover their technology and start using it to explore the galaxy, or is that just a happy (?) accident? Will the two races meet someday? Or, if you like, table all those Big Mysteries for some series finale off in the far distance. Just the premise of flying off to parts unknown in all these Heechee spaceships admits of an infinite variety of adventures. Gene Roddenberry may have once famously pitched Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the Stars,” but the starship Enterprise has got nothing on this idea.

Here’s the thing, though: having come up with this spectacular idea that the likes of a Doc Smith could have spent an entire career milking, Frederik Pohl perversely refused to turn it into the straightforward tales of interstellar adventure that it was crying out to become. Gateway engages with it instead only in the most subversively oblique fashion. Half of the novel consists of a series of therapy sessions involving a robot psychologist and a Gateway prospector named Robinette Broadhead who’s neither conventionally adventurous nor even terribly likable. Robinette is the only survivor — under somewhat suspicious circumstances — of a recent five-person prospecting expedition. He’s now rich, but he’s also a deeply damaged soul, just one of the many who inhabit Gateway, a rather squalid place beset by rampant drug abuse, a symptom of the literal dead-enders who inhabit it between prospecting voyages. We spend far more time exploring the origins and outcomes of Robinette’s various psycho-sexual hangups than we do gallivanting about the stars. It’s as if we wandered into a Star Trek movie and got an Ingmar Bergman film that just happens to be set in space instead. Gateway is a shameless bait-and-switch of a novel. Robinette Broadhead, I’m afraid, lost his sense of wonder a long time ago, and it seems that he took Frederik Pohl’s as well.

The best way to understand Gateway may be through the lens of the times in which it was written: this is very much a novel of the 1970s, that long, hazy morning after to the rambunctious 1960s. The counterculture of the earlier decade had focused on collective struggles for social justice, but the 1970s turned inward to focus on the self. Images of feminist activists like Betty Friedan shouting through bullhorns at rallies were replaced in the media landscape with the sitcom character Mary Tyler Moore, the career gal who really did have it all; rollicking songs of mass protest were replaced by the navel-gazing singer-songwriter movement; the term Me Generation was coined, and suddenly everyone seemed to be in therapy of one kind or another, trying to sort out their personal issues instead of trying to fix society writ large. Meanwhile a pair of global oil crises, acid rain, and the thick layer of smog that hovered continually over Hollywood — the very city of dreams itself — were driving home for the first time what a fragile place this planet of ours actually is. Oh, well… on the brighter side, if you were into that sort of thing, lots of people were having lots and lots of casual sex, still enjoying the libertine sexual mores of the 1960s before the specter of AIDS would rear its head and put an end to all that as well in the following decade.

It’s long been a truism among science-fiction critics that this genre which is ostensibly about our many possible futures usually has far more interesting things to say about the various presents that create it. And nowhere is said truism more true than in the case of Gateway. For better or for worse, all of the aspects of fashionable 1970s culture which I’ve just mentioned fairly leap off its pages: the therapy and accompanying obsessive self-examination, the warnings about ecology and environment, the sex. It was so in tune with its times that the taste-makers of science fiction, who so desperately wanted their favored literary genre to be relevant, able to hold its head up proudly alongside any other, rewarded the novel mightily. Gateway won pretty much everything it was possible for a science-fiction novel to win, including its year’s Hugo and Nebula, the most prestigious awards in the genre; it sold far better than anything else Frederik Pohl had ever written; it made Pohl, four decades on from publishing that first awkward adolescent poem in Amazing Stories, a truly hot author at last.

The modern critical opinion tends to be more mixed. In fact, Gateway stands today as one of the more polarizing science-fiction novels ever written. Plenty of readers find its betrayal of its brilliant space-operatic setup unforgivable, and/or find its unlikable, self-absorbed protagonist insufferable, and/or find its swinging-70s social mores and dated ideas about technology simply silly. I confess that I myself largely belong to this group, although more for the latter two reasons than the first. Other readers, though, continue to find something hugely compelling about the novel that’s never quite come through for me. And yet even some of this group might agree that some aspects of Gateway haven’t aged terribly well. With some of the best writers in the world now embracing or at least acknowledging science fiction as as valid a literary form as any other, the desperate need to prove the genre’s literary bona fides at every turn that marked the 1960s and 1970s no longer exists. Gateway today feels like it’s trying just a bit too hard.

In at least one sense, Gateway did turn into a case of business as usual for a popular genre novel: Frederik Pohl published three sequels plus a collection of Gateway short stories during the 1980s. These gradually peeled back the layers of mystery to reveal who the Heechee were, why they had once come to our solar system, and why they had left, using the same oblique approach that had so delighted and infuriated readers of the first book. None of them had the same lightning-in-a-bottle quality as that first book, however, and Pohl’s reputation gradually declined back to join the mid-tier authors with which he had always been grouped prior to 1977. Perhaps in the long run that was simply where he belonged — a solid writer of readable, enjoyable fiction, but not one overly likely to shift any paradigms inside a reader’s psyche.

At any rate, such was the position Pohl found himself in in early 1991, when Legend Entertainment came calling with a plan to make a computer game out of Gateway.

As a tiny developer and publisher in a fast-growing, competitive industry, Legend was always doomed to lead a somewhat precarious existence. Nevertheless, the first months of 1991 saw them having managed to establish themselves fairly well as the only company still making boxed parser-driven adventure games — the natural heir to Infocom, co-founded by an ex-Infocom author named Bob Bates and publishing games written not only by him but also by Steve Meretzky, the most famous Infocom author of all. Spellcasting 101, the latter’s fantasy farce that had become Legend’s debut product the previous year, was selling quite well, and a sequel was already in the works, as was Timequest, a more serious-minded time-travel epic from Bates.

Taking stock of the situation, Legend realized that they needed to increase the number of games they cranked out in order to consolidate their position. Their problem was that they only had two game designers to call upon, both of whom had other distractions to deal with in addition to the work of designing new Legend adventure games: Bates was kept busy by the practical task of running the company, while Meretkzy was working from home as a freelancer, and as such was also doing other projects for other companies. A Legend “Presentation to Stockholders” dated May of 1991 makes the need clear: “We need to find new game authors,” it states under the category of “Product Issues.” Luckily, there was already someone to hand — in fact, someone who had played a big part in drawing up the very document in question — who very much wanted to design a game.

Mike Verdu had been Bates’s partner in Legend Entertainment from the very beginning. Although not yet out of his twenties, he was already an experienced entrepreneur who had founded, run, and then sold a successful business. He still held onto his day job with ASC, the computer-services firm with many Defense Department contracts which had acquired the aforementioned business, even as he was devoting his evenings and weekends to Legend. Verdu:

I was the business guy. I was the CFO, the COO, the guy who went and got money and made sure we didn’t run out of it, who figured out the production plans for the products, tried to get them done on time, figured out the milestone plans and the software-development plans. I was a product guy inasmuch as I was helping to hire programmers and putting them to work, but I wasn’t a game designer, and I wasn’t writing code or being the creative director on products. And I really wanted to do that.

So, there was this moment when I had to decide between continuing to work with ASC and doing Legend part time or doing Legend full time. I decided to do Legend full time. But as a condition of that, I said, “I’d like to be a part of the teams that are actually making the games.”

But I didn’t believe I had the chops to create a whole world and write a game from scratch. I was sort of looking for a world I could tell a story in. So I talked to Bob about licensing. I was incredibly passionate about Frederik Pohl’s novels. So we talked about Gateway, and Bob made the connection and negotiated the deal. It went so much smoother and easier than I thought it would. I was so excited!

The negotiations were doubtless sped along by the fact that the bloom was already somewhat off the rose when it came to Gateway. The novel’s sequels had been regarded by even many fans of the original as a classic case of diminishing returns, and the whole body of work, which so oozed that peculiar malaise of the 1970s, felt rather dated when set up next to hipper, slicker writers of the 1980s like William Gibson. Nobody, in short, was clamoring to license Gateway for much of anything by this point, so a deal wasn’t overly hard to strike.

Just like that, Mike Verdu had his world to design his game in, and Legend was about to embark on their first foray into a type of game that would come to fill much of their catalog in subsequent years: a literary license. For this first time out, they were fortunate enough to get the best kind of literary license, short of the vanishingly rare case of one where an active, passionate author is willing to serve as a true co-creator: the kind where the author doesn’t appear to be all that interested in or even aware of the project’s existence. Mike Verdu never met or even spoke to Frederik Pohl in the process of making what would turn out to be two games based on his novels. He got all the benefits of an established world to play in with none of the usual drawbacks of having to ask for approval on every little thing.

Yet the Gateway project didn’t remain Verdu’s baby alone for very long. Bates and Verdu, eager to expand their stable of game designers yet further, hit upon the idea of using it as a sort of training ground for other current Legend employees who, like Verdu, dreamed of breaking into a different side of the game-development business. Verdu agreed to divide his baby into three pieces, taking one for himself and giving the others to Glen Dahlgren, a Legend programmer, and to Michael Lindner, the company’s music-and-sound guru. All would work on their parts under the loose supervision of the experienced Bob Bates, who stood ready to gently steer them back on course if they started to stray. Verdu:

We learned how to write code. We learned the craft of interactive-fiction design from Bob, then we would huddle as a group and hash out the storylines and puzzles for our respective sections of the game, then try to tie them all together. That was one of the best times of my career, turning from a defense-industry executive into a game designer who could write code and bring a game to life. Magical… incredibly great!

You were writing, compiling, and testing in this constant iteration. You would write something, then you would see the results, then repeat. I think that was the most powerful flow state I’ve ever been in. Hours would just evaporate. I’d look up at four in the morning and there’d be nobody in the office: Good God, where did the last eight hours go? It was a wonderful creative process.

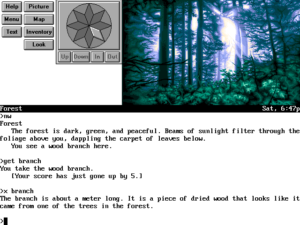

It was an unorthodox, perhaps even disjointed way to make a game, but the Legend Trade School for Game Design worked out beautifully. When it shipped in the summer of 1992, Gateway was by far the best thing Legend had done to that point: a big, generous, well-polished game, with lots to see and do, a nice balance between plot and free-form exploration, and meticulously fair puzzle design. It’s the adventure-game equivalent of a summer beach read, a page turner that just keeps rollicking along, ratcheting up the excitement all the while. It isn’t a hard game, but you wouldn’t want it to be; this is a game where you just want to enjoy the ride, not scratch your head for long periods of time over its puzzles. It even looks much better than the occasionally garish-looking Legend games which came before it, thanks to the company’s belated embrace of 256-color VGA graphics and their growing comfort working with multimedia elements.

You might already be sensing a certain incongruity between this description of Gateway the game and my earlier description of Gateway the novel. And, indeed, said incongruity is very much present. A conventional object-oriented adventure game is hardly the right medium for delving deep into questions of individual psychology. A player of a game needs a through line to follow, a set of concrete goals to achieve; this explains why adventure games share their name with adventure fiction rather than literary fiction. Do you remember how I described Gateway the novel as setting up a perfect space-opera premise, only to obscure it behind therapy sessions and a disjointed, piecemeal approach to its narrative? Well, Gateway the game becomes the very space opera that the novel seemed to promise us, only to jerk it away: a big galaxy-spanning romp that Doc Smith could indeed have been proud of. Mike Verdu, the designer most responsible for the overarching structure of the game, jettisoned Pohl’s sad-sack protagonist along with all of his other characters. He also dispensed with the foreground plot, such as it is, about personal guilt and responsibility that drives the novel. What he was left with was the glorious wide-frame premise behind it all.

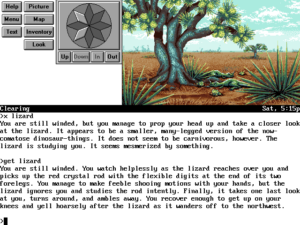

The game begins with you, a lucky (?) lottery winner from the troubled Earth, arriving at Gateway Station to take up the job of prospector. In its first part, written by Mike Verdu, you acclimate to life on the station, complete your flight training, and go on your initial prospecting mission. In the second part, written by Michael Lindner, you tackle a collection of prospecting destinations in whatever order you prefer, visiting lots of alien environments and assembling clues about who the Heechee were and why they’ve disappeared. In part three, written by Glen Dahlgren, you have to avert a threat to Earth posed by another race of aliens known as the Assassins — that race being the reason, you’ve only just discovered to your horror, that the Heechee went into hiding in the first place. The plot as a whole is expansive and improbable and, yes, more than a little silly. In other words, it’s space opera at its best. There’s nothing wrong with a little pure escapism from time to time.

Gateway the game thus becomes, in my opinion anyway, an example of a phenomenon more common than one might expect in creative media: the adaptation that outdoes its source material. It doesn’t even try to carry the same literary or thematic weight that the novel rather awkwardly stumbles along under, but by way of compensation it’s a heck of a lot more fun. As an adaptation, it fails miserably if one’s criterion for success is capturing the unadulterated flavor and spirit of the source material. As a standalone adventure game, however, it’s a rollicking success.

Legend had signed a two-game deal with Frederik Pohl right from the start, and had always intended to develop a sequel to Gateway if its sales made that idea viable. And so, when the first Gateway sold a reasonable 35,000 units or so, Gateway II: Homeworld got the green light. Michael Lindner had taken on another project of his own by this point, so Mike Verdu and Glen Dahlgren divided the sequel between just the two of them, each taking two of the sequel’s four parts.

Reaching stores almost exactly one year after its predecessor, Gateway II became both the last parser-driven adventure Legend published and the last boxed game of that description from any publisher — a melancholy milestone for anyone who had grown up with Infocom and their peers during the previous decade. The text adventure would live on, but it would do so outside the conventional computer-game industry, in the form of games written by amateurs and moonlighters that were distributed digitally and usually given away rather than sold. Never again would anyone be able to make a living from text adventures.

As era enders go, though, Gateway II: Homeworld is pretty darn spectacular, with all the same strengths as its predecessor. In its climax, you finally meet the Heechee themselves on their hidden homeworld — thus the game’s subtitle — and save the Earth one final time while you’re at it. It’s striking to compare the driving plot of this game with the static collections of environments and puzzles that had been the text adventures of ten years before. The medium had come a long way from the days of Zork. This isn’t to say that Legend’s latter-day roller-coaster text adventures, sporting music, cut scenes, and heaps of illustrations, were intrinsically superior to the traditional approach — but they certainly were impressive in their degree of difference, and in how much fun they still are to play in their own way.

One thing that Zork and the Gateway games do share is the copious amounts of love and passion that went into making them. Unlike so many licensed games, the Gateway games were made for the right reasons, made by people who genuinely loved the universe of the novels and were passionate about bringing it to life in an interactive medium.

For Mike Verdu, Michael Lindner, and Glen Dahlgren, the Gateway games did indeed mark the beginning of new careers as game designers, at Legend and elsewhere. The story of Verdu, the business executive who became a game designer, is particularly compelling — almost as compelling, one might even say, as that of Frederik Pohl, the mid-tier author, agent, and editor who briefly became the hottest author in science fiction almost five decades after he decided to devote his life to his favorite literary genre, in whatever capacity it would have him. Both men’s stories remind us that, for the lucky among us at least, life is long, and as rich as we care to make it, and it’s a shame to spend it all doing just one thing.

Gateway and Gateway II: Homeworld in Pictures

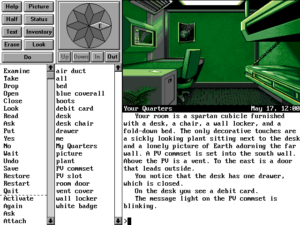

Gateway employs Legend’s standard end-stage-commercial-text-adventure interface, with music and sound and graphics and several screen layouts to choose from, straining to satisfy everyone from the strongly typing-averse to the purists who still scoff at anything more elaborate than a simple stream of text and a blinking command prompt.

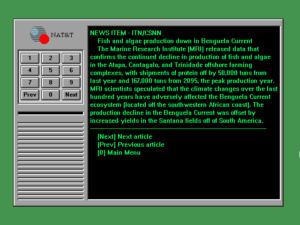

Mike Verdu wanted a license to give him an established world to play with. Having gotten his wish, he used it well. Gateway puts enormous effort into making its environment a rich, living place, building upon what is found in Frederik Pohl’s novels. Much of this has nothing to do with the puzzles or other gameplay elements; it’s there strictly to add to the experience as a piece of fiction. Thanks to an unlimited word count and heaps of new multimedia capabilities, it outdoes anything Infocom could ever have dreamed of doing in this respect.

We spend a big chunk of Gateway II in a strange alien spaceship — the classic “Big Dumb Object” science-fiction plot, reminding us not just of classic novels but of earlier text adventures like Infocom’s Starcross and Telarium’s adaptation of Rendezvous with Rama. In fact, there are some oddly specific echoes of the former game, such as a crystal rod and a sort of zoo of alien lifeforms to deal with. That said, you’ll never mistake one game for the other. Starcross is minimalist in spirit and presentation, a cerebral exercise in careful exploration and puzzle-solving, while Gateway II is just a big old fun-loving thrill ride, full of sound and color, that rarely slows down enough to let you take a breath. I love them both equally.

Many of the illustrations in Gateway II in particular really are lovely to look at, especially when one considers the paucity of resources at Legend’s disposal in comparison to bigger adventure developers like Sierra and LucasArts. There were obviously some fine artists employed by Legend, with a keen eye for doing more with less.

Some of the cut scenes in Gateway II are 3D-modeled. Such scenes were becoming more and more common in games by 1993, as computing hardware advanced and developers began to experiment with a groundbreaking product called 3D Studio. The 3D Revolution, which would change the look and to a large extent the very nature of games as the decade wore on, was already looming in the near distance.

The parser disappeared from Legend’s games not so much all at once as over a series of stages. By Gateway II, the last Legend game to be ostensibly parser-based, conversations and even some puzzles had become purely point-and-click affairs for the sake of convenience and variety. It already feels like you spend almost as much time mousing around as you do typing, even if you don’t choose to use the (cumbersome) onscreen menus of verbs and nouns to construct your commands for the parser. Having come this far, it was a fairly straightforward decision for Legend to drop the parser entirely in their next game. Thus do most eras end — not with a bang but with a barely recognized whimper. At least the parser went out on a high note…

(Sources: I find Frederik Pohl’s memoir The Way the Future Was, about his life spent in science fiction, more compelling than his actual fiction, as I do The Way the Future Blogs, an online journal which he maintained for the last five years or so of his life, filling it with precious reminiscences about his writing, his fellow authors, his nearly century-spanning personal life, and his almost equally lengthy professional career in publishing and fandom. I’m able to tell the Legend Entertainment side of this story in detail thanks entirely to Bob Bates and Mike Verdu, both of whom sat down for long interviews, the former of whom also shared some documents from those times.

Feel free to download the games Gateway and Gateway II, packaged to be as easy as possible to get running under DOSBox on your modern computer, from right here. As noted in the article proper, they’re great rides that are well worth your time, two of the standout gems of Legend’s impressive catalog.)