By 1990, the world of adventure games was coming to orient itself after the twin poles of Sierra Online and LucasFilm Games. The former made a lot of games, on diverse subjects and of diverse quality, emphasizing always whatever new audiovisual flash was made possible by the very latest computing technology. The latter, on the other hand, made far fewer and far less diverse but more careful games, fostering a true designer’s culture that emphasized polish over flash. In their attitudes toward player-character death and dead ends, toward puzzle design, toward graphics style, each company had a distinct personality, and adventure-game fans lined up, as they continue to do even today, as partisans of one or the other.

Yet in the vast territory between these two poles were many other developers experimenting with the potential of adventure games, and in many cases exploring approaches quite different from either of the two starring players. One of the more interesting of these supporting players was the Oregon-based Dynamix, who made five adventure or vaguely adventure-like games between 1988 and 1991 — as many adventure-like games, in fact, as LucasFilm Games themselves managed to publish during the same period. Despite this relative prolificacy, Dynamix was never widely recognized as an important purveyor of adventures; they enjoyed their greatest fame in the very different realm of 3D vehicular simulations. There are, as we’ll see, some pretty good reasons for that to be the case; for all their surprisingly earnest engagement with interactive narrative, none of the five games in question managed to rise to the level of a classic. Still, they all are, to a one, interesting at the very least, which is a track record few other dabblers in the field of adventure games can lay claim to.

Arcticfox, Dynamix’s breakout hit, arrived when Electronic Arts was still nursing the remnants of Trip Hawkins’s original dream of game developers as rock stars, leading to lots of strange photos like this one. This early incarnation of Dynamix consisted of (from left to right) Kevin Ryan, Jeff Tunnell, Damon Slye, and Richard Hicks.

Like a number of other early software developers, Dynamix was born on the floor of a computer shop. The shop in question was The Computer Tutor of Eugene, Oregon, owned and operated in the early 1980s by a young computer fanatic named Jeff Tunnell (the last name is pronounced with the accent on the second syllable, like “Raquel” — not like “tunnel”). He longed to get in on the creative end of software, but had never had the patience to progress much beyond BASIC as a programmer in his own right. Then came the day when one of his regular customers, a University of Oregon undergraduate named Damon Slye, showed him a really hot Apple II action game he was working on. Tunnell knew opportunity when he saw it.

Thus was born a potent partnership, one not at all removed from the similar partnership that had led to MicroProse Software on the other coast. Jeff Tunnell was the Wild Bill Stealey of this pairing: ambitious, outgoing, ready and willing to tackle the business side of software development. Damon Slye was the Sid Meier: quiet, a little shy, but one hell of a game programmer.

Tunnell and Slye established their company in 1983, at the tail end of the Ziploc-bag era of software publishing, under the dismayingly generic name of The Software Entertainment Company. They started selling the game that had sparked the company, which Slye had now named Stellar 7, through mail order. The first-person shoot-em-up put the player in charge of a tank lumbering across the wire-frame surface of an enemy-infested planet. It wasn’t the most original creation in the world, owing a lot to the popular Atari quarter-muncher Battlezone, but 3D games of this sort were unusual on the Apple II, and this one was executed with considerable aplomb. A few favorable press notices led to it being picked up by Penguin Software in 1984, which in turn led to Tunnell selling The Computer Tutor in order to concentrate on his new venture. (Unbeknownst to Tunnell and Slye at the time, Stellar 7 was purchased and adored by Tom Clancy, author of one of the most talked-about books of the year. “It is so unforgiving,” he would later say. “It is just like life. It’s just perfect to play when I’m exercising. I get on my exercycle, start pedaling, pick up the joystick, and I’m off…”)

But the life of a small software developer just as the American home-computer industry was entering its first slump wasn’t an easy one. Tunnell signed contracts wherever he could find them to keep his head above water: releasing Sword of Kadash, an adventure/CRPG/platformer hybrid masterminded by another kid from The Computer Tutor named Chris Cole; writing a children’s doodler called The Electronic Playground himself with a little help from Damon Slye; even working on a simple word processor for home users.

In fact, it was this last which led to the company’s big break. They had chosen to write that program in C, a language which wasn’t all that common on the first generation of 8-bit microcomputers but which was officially blessed as the best way to program a new 16-bit audiovisual powerhouse called the Commodore Amiga. Their familiarity with C gave Tunnell’s company, by now blessedly renamed Dynamix, an in with Electronic Arts, the Amiga’s foremost patron in the software world, who were looking for developers to create products for the machine while it was still in the prototype phase. Damon Slye thus got started programming Arcticfox on an Amiga that didn’t even have a functioning operating system, writing and compiling his code on an IBM PC and sending it over to the Amiga via cable for execution.

Conceptually, Arcticfox was another refinement on the Battlezone/Stellar 7 template, another tooling-around-and-shooting-things-in-a-tank game. As a demonstration of the Amiga’s capabilities, however, it was impressive, replacing its predecessors’ monochrome wire-frame graphics with full-color solids. Reaching store shelves in early 1986 as part of the first wave of Amiga games, Arcticfox was widely ported and went on to sell over 100,000 copies in all, establishing Dynamix’s identity as a purveyor of cutting-edge 3D graphics. In that spirit, the next few years would bring many more 3D blast-em games, with names like Skyfox II, F-14 Tomcat, Abrams Battle Tank, MechWarrior, Deathtrack, and A-10 Tank Killer.

Yet even in the midst of all these adrenaline-gushers, Jeff Tunnell was nursing a quiet interest in the intersection of narrative with interactivity, even as he knew that he didn’t want to make a traditional adventure game of either the text or the graphical stripe. Like many in his industry by the second half of the 1980s, he believed the parser was hopeless as a long-term sell to the mass market, while the brittle box of puzzles that was the typical graphic adventure did nothing for him either. He nursed a dream of placing the player in a real unfolding story, partially driving events but partially being driven by them, like in a movie. Of course, he was hardly alone at the time in talking about “interactive movies”; the term was already becoming all the rage. But Dynamix’s first effort in that direction certainly stood out from the pack — or would have, if fate had been kinder to it.

Jeff Tunnell still calls Project Firestart the most painful single development project he’s ever worked on over the course of more than three decades making games. Begun before Arcticfox was published, it wound up absorbing almost three years at a time when the average game was completed in not much more than three months. By any sane standard, it was just way too much game for the Commodore 64, the platform for which it was made. It casts the player as a “special agent” of the future named Jon Hawking, sent to investigate a spaceship called the Prometheus that had been doing controversial research into human genetic manipulation but has suddenly stopped communicating. You can probably guess where this is going; I trust I won’t be spoiling too much to reveal that zombie-like mutants now roam the ship after having killed most of the crew. The influences behind the story Tunnell devised aren’t hard to spot — the original Alien movie being perhaps foremost among them — but it works well enough on its own terms.

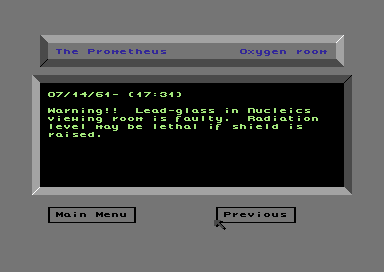

In keeping with Tunnel’s commitment to doing something different with interactive narrative, Project Firestart doesn’t present itself in the guise of a traditional adventure game. Instead it’s an action-adventure, an approach that was generally more prevalent among British than American developers. You explore the ship’s rooms and corridors in real time, using a joystick to shoot or avoid the monsters who seem to be the only life remaining aboard the Prometheus. What makes it stand out, however, is the lengths Dynamix went to to make it into a real unfolding story with real stakes. As you explore, you come across computer terminals holding bits and pieces of what has happened here, and of what you need to do to stop the contagion aboard from spreading further. You have just two hours, calculated in real playing time, to gather up all of the logs you can for the benefit of future researchers, make contact with any survivors from the crew who might have managed to hole up somewhere, set the ship’s self-destruct mechanism, and escape. You’re personally expendable; if you exceed the time limit, warships that are standing by will destroy the Prometheus with you aboard.

Throughout the game, cinematic touches are used to build tension and drama. For example, when you step out of an elevator to the sight of your first dead body, a stab of music gushes forth and the “camera” cuts to a close-up of the grisly scene. Considering what a blunt instrument Commodore 64 graphics and sound are, the game does a rather masterful job of ratcheting up the dread, whilst managing to sneak in a plot twist or two that even people who have seen Alien won’t be able to anticipate. Ammunition is a scarce commodity, leaving you feeling increasingly hunted and desperate as the ship’s systems begin to fail and the mutants relentlessly hunt you down through the claustrophobic maze of corridors. And yet, tellingly, Project Firestart diverges from the British action-adventure tradition in not being all that hard of a game in the final reckoning. You can reasonably expect to win within your first handful of tries, if perhaps not with the most optimal ending. It’s clearly more interested in giving you a cinematic experience than it is in challenging you in purely ludic terms.

Project Firestart was finally released in 1988, fairly late in the day for the Commodore 64 in North America and just as Tunnell was terminating his publishing contract with Electronic Arts under less-than-entirely-amicable terms and signing a new deal with Mediagenic. It thus shipped as one of Dynamix’s last games for Electronic Arts, received virtually no promotion, and largely vanished without a trace; what attention it did get came mostly from Europe, where this style of game was more popular in general and where the Commodore 64 was still a strong seller. But in recent years it’s enjoyed a reevaluation in the gaming press as, as the AV Club puts it, “a forgotten ’80s gem” that “created the formula for video game horror.” It’s become fashionable to herald it as the great lost forefather of the survival-horror genre that’s more typically taken to have been spawned by the 1992 Infogrames classic Alone in the Dark.

Such articles doubtless have their hearts in the right place, but in truth they rather overstate Project Firestart‘s claim to such a status at the same time that they rather understate its weaknesses. While the mood of dread the game manages to evoke with such primitive graphics and sound is indeed remarkable, it lacks any implementation of line of sight, and thus allows for no real stealth or hiding; the only thing to do if you meet some baddies you don’t want to fight is to run into the next room. If it must be said to foreshadow any future classic, my vote would go to Looking Glass Studio’s 1994 System Shock rather than Alone in the Dark; System Shock too sees you gasping with dread as you piece together bits of a sinister story from computer terminals, even as the monsters of said story hunt you down. But even on the basis of that comparison Project Firestart remains more of a formative work than a classic in its own right. Its controls are awkward; you can’t even move and shoot at the same time. And, rather than consisting of a contiguous free-scrolling world, its geography is, due to technical limitations, segmented into rooms which give the whole a choppy, disconnected feel, especially given that they must each be loaded in from the Commodore 64’s achingly slow disk drive.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given Project Firestart‘s protracted and painful gestation followed by its underwhelming commercial performance, Dynamix themselves never returned to this style of game. Yet it provided the first concrete manifestation of Jeff Tunnell’s conception of game narrative as — appropriately enough given the name of his company — a dynamic thing which provokes the player as much as it is provoked by her. Future efforts would gradually hew closer, on a superficial level at least, to the form of more traditional adventure games without abandoning this central conceit.

That said, the next narrative-oriented Dynamix game would still be an oddball hybrid by anyone’s standard. By 1989, Dynamix, like an increasing number of American computer-game developers, had hitched their wagon firmly to MS-DOS, and thus David Wolf: Secret Agent appeared only on that platform. It was intended to be an interactive James Bond movie.

But intention is not always result. To accept Dynamix’s own description of David Wolf as an interactive movie is to be quite generous indeed. It’s actually a non-interactive story, presented as a series of still images with dialog overlaid, interspersed with a handful of vehicular action games that feel like fragments Dynamix just happened to have lying around the office: a hang-glider sequence, a jet-fighter sequence, a car chase, the old jumping-out-of-an-airplane-without-a-parachute-just-behind-a-villain-who-does-have-one gambit. If you succeed at these, you get to watch more static story; if you fail, that’s that. Or maybe not: in a telling statement as to what was really important in the game, Dynamix made it possible to bypass any minigame at which you failed with the click of a button and keep right on trucking with the story. In a perceptive review for Computer Gaming World magazine, Charles Ardai compared David Wolf to, of all things, the old arcade game Ms. Pac-Man. The latter featured animated “interludes” every few levels showing the evolving relationship between Mr. and Mrs. Pac-Man. These served, Ardai noted, as the icing on the cake, a little bonus to reward the player’s progress. But David Wolf inverted that equation: the static story scenes were now the cake. The game existed “just for the sheer joy of seeing digitized images on your PC.”

Our hero David Wolf starts salivating over the game’s lone female as soon as he sees her picture during his mission briefing, and he and the villains spend most of the game passing her back and forth like a choice piece of meat.

These days, of course, seeing pixelated 16-color digitizations on the screen prompts considerably less joy, and the rest of what’s here is so slight that one can only marvel at Dynamix’s verve in daring to slap a $50 suggested list price on the thing. The whole game is over within an hour or so, and a cheesy hour it is at that; it winds up being more Get Smart than James Bond, with dialog that even Ian Fleming would have thought twice about before committing to the page. (A sample: “Garth, I see your temper is still intact. Too bad I can’t say the same for your sense of loyalty.”) It’s difficult to tell to what extent the campiness is accidental and to what extent it’s intentional. Charles Ardai:

The viewer isn’t certain how to take the material. Is it a parody of James Bond (which is, by now, self-parodic), a straight comic adventure (imitation Bond as opposed to parody), or a serious thriller? It is hard to take the strictly formula plot seriously, but several of the scenes suggest that one is supposed to. I suspect that the screenwriters never quite decided which direction to take, and hoped to be able to do with a little of each. This can’t possibly work. You can’t both parody a genre and, at the same time, place yourself firmly within that genre because the resulting self-parody looks embarrassingly unwitting. Certainly you can’t do this and expect to be taken seriously. Airplane! couldn’t ask us to take seriously its disaster plot and Young Frankenstein didn’t try to make viewers cry over the monster’s plight, but this is what the designers of David Wolf seem to be doing.

Such wild vacillations in tone are typical of amateur writers who haven’t yet learned to control their wayward pens. They’re thus all too typical as well of the “programmer-written” era of games, before hiring real writers became standard industry practice. David Wolf wouldn’t be the last Dynamix game to suffer from the syndrome.

The cast of David Wolf manages the neat trick of coming off as terrible actors despite having only still images to work with. Here they’re trying to look shocked upon being surprised by villains pointing guns at them.

But for all its patent shallowness, David Wolf is an interesting piece of gaming history for at least a couple of reasons. Its use of digitized actors, albeit only in still images, presaged the dubious craze for so-called “full-motion-video” games that would dominate much of the industry for several years in the 1990s. (Tellingly, during its opening credits David Wolf elects to list its actors, drawn along with many of the props they used from the University of Oregon’s theatrical department, in lieu of the designers, programmers, and artists who actually built the game; they have to wait until the end scroll for recognition.) And, more specifically to the context of this article, David Wolf provides a further illustration of Jeff Tunnell’s vision of computer-game narratives that weren’t just boxes of puzzles.

Much of the reason David Wolf wound up being such a constrained experience was down to Dynamix being such a small developer with fairly scant resources. Tunnell was therefore thrilled when an arrangement with the potential to change that emerged.

At some point in late 1989, Ken Williams of Sierra paid Dynamix a visit. Flight simulations and war games of the sort in which Dynamix excelled were an exploding market (no pun intended!) at the time, one which would grow to account for 35.6 percent of computer-game sales by the second half of 1990, dwarfing the 26.2 percent that belonged to Sierra’s specialty of adventure games. Williams wanted a piece of that exploding market. He was initially interested only in licensing some of Dynamix’s technology as a leg-up. But he was impressed enough by what he saw there — especially by a World War I dog-fighting game that the indefatigable Damon Slye had in the works — that the discussion of technology licensing turned into a full-on acquisition pitch. For his part, Jeff Tunnell, recognizing that the games industry was becoming an ever more dangerous place for a small company trying to go it alone, listened with interest. On March 27, 1990, Sierra acquired Dynamix for $1.5 million.

In contrast to all too many such acquisitions, neither party would come to regret the deal. Even in the midst of a sudden, unexpected glut in World War I flight simulators, Damon Slye’s Red Baron stood out from the pack with a flight model that struck the perfect balance between realism and fun. (MicroProse had planned to use the same name for their own simulator, but were forced to go with the less felicitious Knights of the Sky when Dynamix beat them to the trademark office by two weeks.) Over the Christmas 1990 buying season, Red Baron became the biggest hit Dynamix had yet spawned, proving to Ken Williams right away that he had made the right choice in acquiring them.

Williams and Tunnell maintained a relationship of real cordiality and trust, and Dynamix was given a surprising amount of leeway to set their own agenda from offices that remained in Eugene, Oregon. Tunnell was even allowed to continue his experiments with narrative games, despite the fact that Sierra, who were churning out a new adventure game of their own every couple of months by this point, had hardly acquired Dynamix with an eye to publishing still more of them.

And so Dynamix’s first full-fledged adventure game, with real interactive environments, puzzles, and dialog menus, hit the market not long after the acquisition was finalized. Rise of the Dragon had actually been conceived by Jeff Tunnell before David Wolf was made, only to be shelved as too ambitious for the Dynamix of 1988. But the following year, with much of the technical foundation for a real adventure game already laid down by David Wolf, they had felt ready to give it a go.

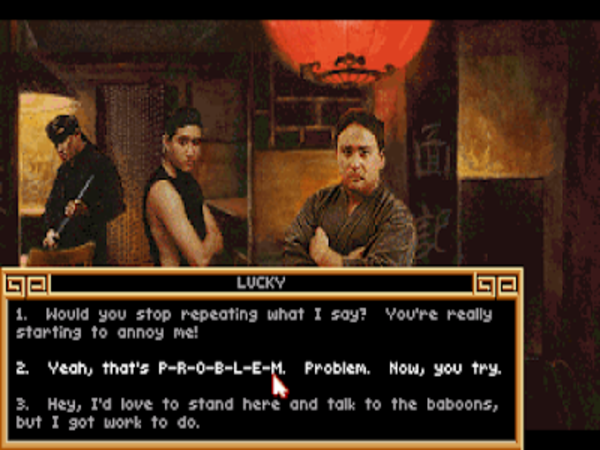

Rise of the Dragon found Dynamix once again on well-trodden fictional territory, this time going for a Bladerunner/Neuromancer cyberpunk vibe; the game’s setting is the neon-lit Los Angeles of a dystopic future of perpetual night and luscious sleaze. You play a fellow stamped with the indelible name of Blade Hunter, a former cop who got himself kicked off the force by playing fast and loose with the rules. Now, he works as a private detective for whoever can pay him. When the game begins, he’s just been hired by the mayor to locate his drug-addicted daughter, who has been swallowed up by the city’s underworld. As a plot like that would indicate, this is a game that very much wants to be edgy. King’s Quest it isn’t.

There are a lot of ideas in Rise of the Dragon, some of which work better than others, but all of which reflect a real, earnest commitment to a more propulsive form of interactive narrative than was typical of the new parent company Sierra’s games. Jeff Tunnell:

Dynamix adventures have an ongoing story that will unfold even if the player does nothing. The player needs to interact with the game world to change the outcome of that story. For example, if the player does nothing but sit in the first room of Dragon, he will observe cinematic “meanwhile cutaways” depicting the story of drug lord Deng Hwang terrorizing the futuristic city of Los Angeles with tainted drug patches that cause violent mutations. So the player’s job is to interact with the world and change the outcome of the story to one that is more pleasing and heroic.

The entire game runs in real time, with characters coming and going around the city on realistic schedules. Dialog is at least as important as object-based puzzle-solving, and characters remember how you treat them to an impressive degree. This evolving web of relationships, combined with a non-linear structure and multiple solutions to most dilemmas, creates a possibility space far greater than the typical adventure game, all set inside a virtual world which feels far more alive.

The interface as well goes its own way. The game uses a first-person rather than third-person perspective, a rarity in graphic adventures of this period. And, at a time when both Sierra and Lucasfilm Games were still presenting players with menus of verbs to click on, Rise of the Dragon debuted a cleaner single-click system: right-clicking on an object will examine it, left-clicking will take whatever action is appropriate to that object. Among its other virtues, the interface frees up screen real estate to present the striking graphics to maximum effect. Instead of continuing to rely on live actors, Dynamix hired veteran comic-book illustrator Robert Caracol to draw most of the scenery with pen and ink for digitization. Combined with the jump from 16-color EGA to 256-color VGA graphics, the new approach results in art worthy of a glossy, stylized graphic novel. Computer Gaming World gave the game a well-deserved “Special Award for Artistic Achievement” in their “Games of the Year” awards for 1990.

Just to remind us of who made the game, a couple of action sequences do pop up, neither of them all that notably good or bad. But, once again, failing at one of them brings an option to skip it and continue with the story as if you’d succeeded. Indeed, the game as a whole evinces a forgiving nature that’s markedly at odds both with its hard-bitten setting and with those other adventure games being made by Dynamix’s parent company. It may be possible to lock yourself out of victory or run out of time to solve the mystery, but you’d almost have to be willfully trying to screw up in order to do so. That Dynamix was able to combine this level of forgivingness with so much flexibility in the narrative is remarkable.

But there are flies in the ointment that hold the game back from achieving classic status. Perhaps inevitably given the broad possibility space, it’s quite a short game on any given playthrough, and once the story is known the potential interest of subsequent playthroughs is, to say the least, limited. Of course, this isn’t so much of a problem today as it was back when the game was selling for $40 or more. Other drawbacks, however, remain as problematic as ever. The interface, while effortless to use in many situations, is weirdly obtuse in others. The inventory system in particular, featuring a paper-doll view of Blade Hunter and employing two separate windows in the form of a “main” and a “quick” inventory, is far too clever for its own good. I also find it really hard to understand where room exits are and how the environment fits together. And the writing is once again on the dodgy side; it’s never entirely clear whether Blade Hunter is supposed to be a real cool cat (like the protagonist of Neuromancer the novel) or a lovable (?) loser (like the protagonist of Neuromancer the game). Add to these issues an impossible-to-take-seriously plot that winds up revolving around an Oriental death cult, plus some portrayals of black and Chinese people that border on the outright offensive, and we’re a long way from even competent comic-book fiction.

Still, Rise of the Dragon in my opinion represents the best of Jeff Tunnell’s experiments with narrative games. If you’re interested in exploring this odd little cul-de-sac in adventure-gaming history, I recommend it as the place to start, as it offers by far the best mix of innovation and playability, becoming in the process the best all-around expression of just where Tunnell was trying to go with interactive narrative.

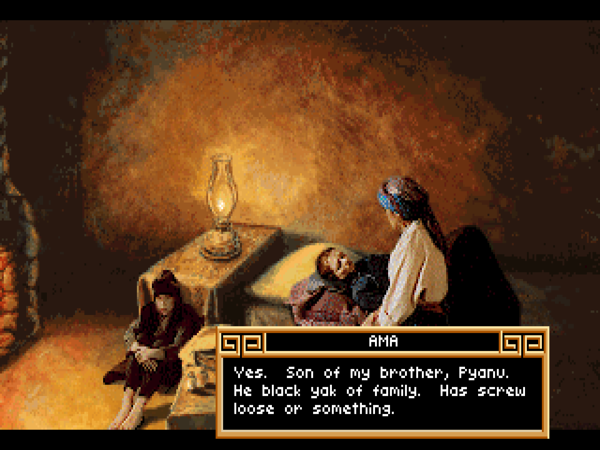

Heart of China, the early 1991 follow-up to Rise of the Dragon, superficially appears to be more of the same in a different setting. The same engine and interface are used, including a couple more action-based mini-games to play or skip, with the genre dance taking us this time to a 1930s pulp-adventure story in the spirit of Indiana Jones. The most initially obvious change is the return to a heavy reliance on digitized “actors.” Dynamix wound up employing some 85 separate people on the business end of their cameras in a production which overlapped with that of Rise of the Dragon, with its beginning phases stretching all the way back into 1989. Thankfully, the integration of real people with computer graphics comes off much better than it does in David Wolf, evincing much more care on the part of the team responsible. Heart of China thus manages to become one of the less embarrassing examples of a style of graphics that was all but predestined to look hopelessly cheesy about five minutes after hitting store shelves.

I’m not sure if this is Really Bad Writing that expects to be taken seriously or Really Bad Writing that’s trying (and failing) to be funny. I’m quite sure, however, that it’s Really Bad Writing of some sort.

When you look more closely at the game’s design, however, you see a far more constrained approach to interactive storytelling than that of its predecessor. You play a down on-his-luck ex-World War I flying ace named “Lucky” Jake Masters. (If there was one thing Dynamix knew how to do, it was to create stereotypically macho names.) He’s running a shady air-courier/smuggling business out of Hong Kong when he’s enlisted by a wealthy “international business tycoon and profiteer” to rescue his daughter, who’s been kidnapped by a warlord deep inside the Chinese mainland. (If there was one thing Dynamix didn’t know how to do, it was to create plots that didn’t involve rescuing the daughters of powerful white men from evil Chinese people.) The story plays out in a manner much more typical of a plot-heavy adventure game — i.e., as a linear series of acts to be completed one by one — than does that of its predecessor. Jeff Tunnell’s commitment to his original vision for interactive narrative was obviously slipping in the face of resource constraints and a frustration, shared by some of his contemporaries who were also interested in more dynamic interactive storytelling, that gamers didn’t really appreciate the extra effort anyway. His changing point of view surfaces in a 1991 interview:

From a conceptual standpoint, multiple plot points are exciting. But when you get down to the implementation, they can make game development an absolute nightmare. Then, after all of the work to implement these multiple paths and endings, we’ve found that most gamers never even discover them.

When the design of Heart of China does allow for some modest branching, Dynamix handles it in rather hilariously passive-aggressive fashion: big red letters reading “plot branch” appear on the screen. Take that, lazy gamers!

Heart of China bears all the signs of a project that was scaled back dramatically in the making, a game which wound up being far more constrained and linear than had been the original plan. Yet it’s not for this reason that I find it to be one of the more unlikable adventure games I’ve ever played. The writing is so ludicrously terrible that one wants to take the whole thing as a conscious B-movie homage of the sort Cinemaware loved to make. But darned if Dynamix didn’t appear to expect us to take it seriously. “It has more depth and sensibility than I’ve ever seen in a computer storytelling game,” said Tunnell. It’s as if he thought he had made Heart of Darkness when he’d really made Tarzan the Ape-Man. The ethnic stereotyping manages to make Rise of the Dragon look culturally sensitive, with every Chinese character communicating in the same singsong broken English. And as for Lucky Jake… well, he’s evidently supposed to be a charming rogue just waiting for Harrison Ford to step into the role, but hitting those notes requires far, far more writerly deftness than anyone at Dynamix could muster. Instead he just comes off as a raging asshole — the sort of guy who creeps out every woman he meets with his inappropriate comments; the sort of guy who warns his friend-with-benefits that she’s gained a pound or two and thus may soon no longer be worthy of his Terrible Swift Sword. For all these reasons and more, I can recommend Heart of China only to the truly dedicated student of adventure-game history.

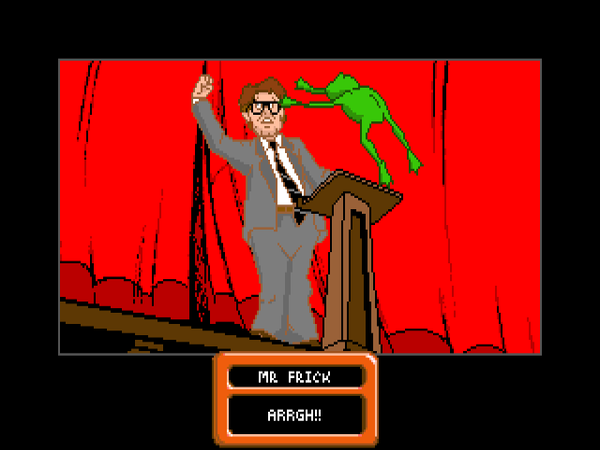

The third and final point-and-click adventure game created by Jeff Tunnell and Dynamix is in some ways the most impressive of them all and in others the most disappointing, given that it turns into such a waste of potential. Tunnell took a new tack with The Adventures of Willy Beamish, deciding to create a light-hearted comedic adventure that would play like a Saturday-morning cartoon. Taking advantage of a lull in Hollywood’s cartoon-production factories, he hired a team of professional animators of the old-school cel-based stripe, veterans of such high-profile productions as The Little Mermaid, Jonny Quest, and The Simpsons, along with a husband-and-wife team of real, honest-to-God professional television writers to create a script. Dynamix’s offices came to look, as a Computer Gaming World preview put it, like a “studio in the golden age of animation,” with animators “etching frantically atop the light tables” while “pen-and-pencil images of character studies, backgrounds, and storyboard tests surround them on the office walls.” The team swelled to some fifty people before all was said and done, making Willy Beamish by far the most ambitious and expensive project Dynamix had ever tackled.

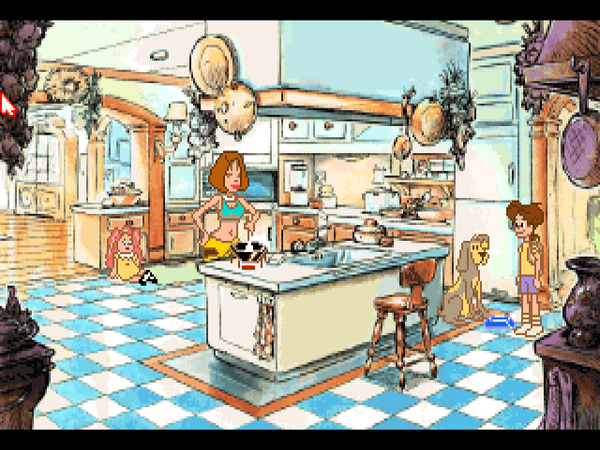

Willy Beamish looked amazing in its time, and still looks just fine today, especially given that its style of hand-drawn cel-based animation is so seldom seen in the post-Pixar era. Look at the amount of detail in this scene!

What Tunnell got for his money was, as noted, darned impressive at first glance. Many companies — not least Sierra with their latest King’s Quest — were making noises about bringing “interactive cartoons” to computer monitors, but Dynamix was arguably the first to really pull it off. Switching to a third-person perspective in keeping with the cartoon theme, every frame was fussed-over to a degree that actually exceeded the likes of The Simpsons, much less the typical Saturday-morning rush job. Tunnel would later express some frustration that the end result may have been too good; he suspected that many people were mentally switching gears and subconsciously seeing it the way they might a cartoon on their television screen, not fully registering that everything they were seeing was playing on their computer. Today, all of this is given a further layer of irony by the way that 3D-rendered computer animation has all but made the traditional cel-based approach to cartoon animation used by Willy Beamish into a dead art. How odd to think that a small army of pencil-wielding illustrators was once considered a sign of progress in computer animation!

The game’s story is a deliberately modest, personal one — which in an industry obsessed with world-shaking epics was a good thing. The young Willy Beamish, a sort of prepubescent version of Ferris Bueller, wants to compete for the Nintari Championship of videogaming, but he and his dubiously named pet frog Horny are at risk of being grounded thanks to a bad mark in his music-appreciation class. From this simple dilemma stems several days of comedic chaos, including a variety of other story beats that involve his whole family. The tapestry was woven together with considerable deftness by the writers, whose experience with prime-time sitcoms served them well. It’s always a fine line between a precocious, smart-Alecky little boy and a grating, bratty one, but The Adventures of Willy Beamish mostly stays on the right side of it. For once, in other words, a Dynamix game has writing to match its ambition.

Unfortunately, the game finds a new way to go off the rails. Rise of the Dragon and Heart of China had combined smart design sensibilities with dodgy writing; Willy Beamish does just the opposite. Like Rise of the Dragon, it runs in real time; unlike Rise of the Dragon, you are given brutally little time to accomplish what you need to in each scene. The game winds up playing almost like a platformer; you have to repeat each scene again and again to learn what to do, then execute perfectly in order to progress. Worse, it’s possible to progress without doing everything correctly, only to be stranded somewhere down the line. The experience of playing Willy Beamish is simply infuriating, a catalog of all the design sins Dynamix adventure games had heretofore been notable for avoiding. I have to presume that all those animators and writers caused Dynamix to forget that they were making an interactive work. As was being proved all over the games industry at the time, that was all too easy to do amidst all the talk about a grand union of Silicon Valley and Hollywood.

Sierra had been a little lukewarm on Dynamix’s previous adventure games, but they gave Willy Beamish a big promotional push for the Christmas 1991 buying season, even grabbing for it the Holy Grail of game promotion: a feature cover of Computer Gaming World. While I’m tempted to make a rude comment here about Dynamix finally making a game that embraced Sierra’s own design standards and them getting excited about that, the reality is of course that the game just looked too spectacular to do anything else. Sierra and Dynamix were rewarded with a solid hit that racked up numbers in the ballpark of one of the former’s more popular numbered adventure series. In 1993, Willy Beamish would even get a re-release as a full-fledged CD-ROM talkie, albeit with some of the most annoying children’s voices ever recorded.

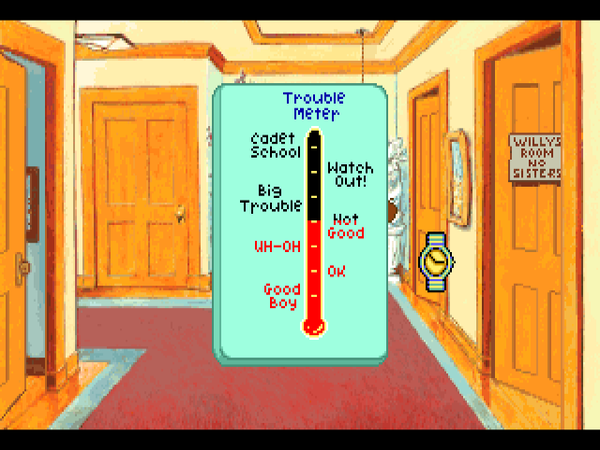

Willy Beamish has a “trouble meter” that hearkens back to Bureaucracy‘s blood-pressure monitor, except this time it’s presumably measuring the blood pressure of the adults around you. If you let it get too high, you get shipped off to boarding school.

But it had been a hugely expensive product to create, and it’s questionable whether its sales, strong though they were, were actually strong enough to earn much real profit. At any rate, Jeff Tunnell, the primary driver behind Dynamix’s sideline in adventure games, suddenly decided he’d had enough shortly after Willy Beamish was finished. It seems that the experience of working with such a huge team had rubbed him the wrong way. He therefore resigned the presidency of Dynamix to set up a smaller company, Jeff Tunnell Productions, “to return to more hands-on work with individual products and to experiment in product genres that do not require the large design teams necessitated by [his] last three designs.” It was all done thoroughly amicably, and was really more of a role change than a resignation; Jeff Tunnell Productions would release their games through Dynamix (and, by extension, Sierra). But Tunnell would never make another adventure game. “After doing story-based games for a while,” he says today, “I realized it wasn’t something I wanted to continue to do. I think there is a place for story in games, but it’s…. hard.” Dynamix’s various experiments with interactive narrative, none of them entirely satisfying, apparently served to convince him that his talents were better utilized elsewhere. Ironically, he made that decision just as CD-ROM, a technology which would have gone a long way toward making his “interactive movies” more than just an aspiration, was about to break through into the mainstream at last.

Still, and for all that it would have been nice to see everything come together at least once for him, I don’t want to exaggerate the tragedy, especially given that the new Jeff Tunnell Productions would immediately turn out a bestseller and instant classic of a completely different type. (More on that in my next article!) If the legacy of Dynamix story games is a bit of a frustrating one, Tunnell’s vision of interactive narratives that are more than boxes of puzzles would eventually prove its worth across a multiplicity of genres. For this reason at the very least, the noble failures of Dynamix are worth remembering.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of July 1988, December 1989, May 1990, February 1991, September 1991, October 1991, November 1991, March 1992, February 1994, and May 1994; Sierra’s news magazines of Summer 1990, Spring 1991, Summer 1991, Fall 1991, and June 1993; InfoWorld of March 5 1984; Apple Orchard of December 1983; Zzap! of July 1989; Questbusters of August 1991; Video Games and Computer Entertainment of May 1991; Dynamix’s hint books for Rise of the Dragon, Heart of China, and The Adventures of Willy Beamish; Matt Barton’s interviews with Jeff Tunnell in Matt Chat 199 and 200; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

You can download emulator-ready Commodore 64 disk images of Project Firestart and a version of David Wolf: Secret Agent that’s all ready to go under DOSBox from right here. Rise of the Dragon, Heart of China, and The Adventures of Willy Beamish — and for that matter Red Baron — are all available for purchase on GOG.com.)