If the tailor goes to war against the baker, he must henceforth bake his own bread.

— Ludwig von Mises

There’s always the danger that an analysis of a game spills into over-analysis. Some aspects of Civilization reflect conscious attempts by its designers to model the processes of history, while some reflect unconscious assumptions about history; some aspects represent concessions to the fact that it first and foremost needs to work as a playable and fun strategy game, while some represent sheer random accidents. It’s important to be able to pull these things apart, lest the would-be analyzer wander into untenable terrain.

Any time I’m tempted to dismiss that prospect, I need only turn to Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich’s ostensible “strategy guide” Civilization: or Rome on 640K a Day, which is actually far more interesting as the sort of distant forefather of this series of articles — as the very first attempt ever to explore the positions and assumptions embedded in the game. Especially given that it is such an early attempt — the book was published just a few months after the game, being largely based on beta versions of same that MicroProse had shared with the authors — Wilson and Emrich do a very credible job overall. Yet they do sometimes fall into the trap of seeing what their political beliefs make them wish to see, rather than what actually existed in the minds of the designers. The book doesn’t explicitly credit which of the authors wrote what, but one quickly learns to distinguish their points of view. And it turns out that Emrich, whose arch-conservative worldview is on the whole more at odds with that of the game than Wilson’s liberal-progressive view, is particularly prone to projection. Among the most egregious and amusing examples of him using the game as a Rorschach test is his assertion that the economy-management layer of Civilization models a rather dubious collection of ideas that have more to do with the American political scene in 1991 than they do with any proven theories of economics.

We know we’re in trouble as soon as the buzzword “supply-side economics” turns up prominently in Emrich’s writing. It burst onto the stage in a big way in the United States in 1980 with the election of Ronald Reagan as president, and has remained to this day one of his Republican party’s main talking points on the subject of economics in general. Its central, counter-intuitive claim is that tax revenues can often be increased by cutting rather than raising tax rates. Lower taxes, goes the logic, provide such a stimulus to the economy as a whole that people wind up making a lot more money. And this in turn means that the government, even though it brings in less taxes per dollar, ends up bringing in more taxes in the aggregate.

In seeing what he wanted to see in Civilization, Alan Emrich decided that it hewed to contemporary Republican orthodoxy not only on supply-side economics but also on another subject that was constantly in the news during the 1980s and early 1990s: the national debt. The Republican position at the time was that government deficits were always bad; government should be run like a business in all circumstances, went their argument, with an orderly bottom line.

But in the real world, supply-side economics and a zero-tolerance policy on deficits tend to be, shall we say, incompatible with one another. Since the era of Ronald Reagan, Republicans have balanced these oil-and-water positions against one another by prioritizing tax cuts when in power and wringing their hands over the deficit — lamenting the other party’s supposedly out-of-control spending on priorities other than their own — when out of power. Emrich, however, sees in Civilization‘s model of an economy the grand unifying theory of his dreams.

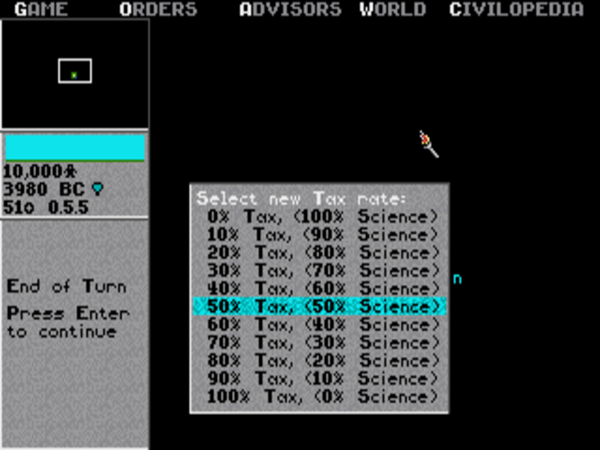

Let’s quickly review the game’s extremely simplistic handling of the economic aspects of civilization-building before we turn to his specific arguments, such as they are. The overall economic potential of your cities is expressed as a quantity of “trade arrows.” As leader, you can devote the percentage of trade arrows you choose to taxes, which add money to your treasury for spending on things like the maintenance costs of your buildings and military units and tributes to other civilizations; research, which lets you acquire new advances; and, usually later in the game, luxuries, which help to keep your citizens content. There’s no concept of deficit spending in the game; if ever you don’t have enough money in the treasury to maintain all of your buildings and units at the end of a turn, some get automatically destroyed. This, then, leads Emrich to conclude that the game supports his philosophy on the subject of deficits in general.

But the more entertaining of Emrich’s arguments are the ones he deploys to justify supply-side economics. At the beginning of a game of Civilization, you have no infrastructure to support, and thus you have no maintenance costs at all — and, depending on which difficulty level you’ve chosen to play at, you may even start with a little bit of money already in the treasury. Thus it’s become standard practice among players to reduce taxes sharply from their default starting rate of 50 percent, devoting the bulk of their civilization’s economy early on to research on basic but vital advances like Pottery, Bronze Working, and The Wheel. With that in mind, let’s try to follow Emrich’s thought process:

To maximize a civilization’s potential for scientific and technological advancement, the authors recommend the following exercise in supply-side economics. Immediately after founding a civilization’s initial city, pull down the Game Menu and select “Tax Rate.” Reduce the tax rate from its default 50% to 10% (90% Science). This reduced rate will allow the civilization to continue to maintain its current rate of expenditure while increasing the rate at which scientific advancements occur. These advancements, in turn, will accelerate the wealth and well-being of the civilization as a whole.

In this way, the game mechanics mirror life. The theory behind tax reduction as a spur to economic growth is built on two principles: the multiplier and the accelerator. The multiplier effect is abstracted out of Sid Meier’s Civilization because it is a function of consumer spending.

The multiplier effect says that each tax dollar cut from a consumer’s tax burden and actually spent on consumer goods will net an additional 50 cents at a second stage of consumer spending, an additional 25 cents at a third stage, an additional 12.5 cents at a fourth stage, etc. Hence, economists claim that the full progression nets a total of two dollars for each extra consumer dollar spent as a result of a tax cut.

The multiplier effect cannot be observed in the game because it is only presented indirectly. Additional consumer spending causes a flash point where additional investment takes place to increase, streamline, and advance production capacity and inventory to meet the demands of the increased consumption. Production increases and advances, in turn, have an additional multiplier effect beyond the initial consumer spending. When the scientific advancements occur more rapidly in Sid Meier’s Civilization, they reflect that flash point of additional investment and allow civilizations to prosper at an ever accelerating rate.

Wow. As tends to happen a lot after I’ve just quoted Mr. Emrich, I’m not quite sure where to start. But let’s begin with his third paragraph, in particular with a phrase which is all too easy to overlook: that for this to work, the dollar cut must “actually be spent on consumer goods.” When tax rates for the wealthy are cut, the lucky beneficiaries don’t tend to go right out and spend their extra money on consumer goods. The most direct way to spur the economy through tax cuts thus isn’t to slash the top tax bracket, as Republicans have tended to do; it’s to cut the middle and lower tax brackets, which puts more money in the pockets of those who don’t already have all of the luxuries they could desire, and thus will be more inclined to go right out and spend their windfall.

But, to give credit where it’s due, Emrich does at least include that little phrase about the importance of spending on consumer goods, even if he does rather bury the lede. His last paragraph is far less defensible. To appreciate its absurdity, we first have to remember that he’s talking about “consumer spending” in a Stone Age economy of 4000 BC. What are these consumers spending on? Particularly shiny pieces of quartz? And for that matter what are they spending, considering that your civilization hasn’t yet developed currency? And how on earth can any of this be said to justify supply-side economics over the long term? You can’t possibly maintain your tax rate of 10 percent forever; as you build up your cities and military strength, your maintenance costs steadily increase, forcing you back toward that starting default rate of 50 percent. To the extent that Civilization can be said to send any message at all on taxes, said message must be that a maturing civilization will need to steadily increase its tax rate as it advances toward modernity. And indeed, as we learned in an earlier article in this series, this is exactly what has happened over the long arc of real human history. Your economic situation at the beginning of a game of Civilization isn’t some elaborate testimony to supply-side economies; it just reflects the fact that one of the happier results of a lack of civilization is the lack of a need to tax anyone to maintain it.

In reality, then, the taxation model in the game is a fine example of something implemented without much regard for real-world economics, simply because it works in the context of a strategy game like this one. Even the idea of such a centralized system of rigid taxation for a civilization as a whole is a deeply anachronistic one in the context of most societies prior to the Enlightenment, for whose people local government was far more important than some far-off despot or monarch. Taxes, especially at the national level, tended to come and go prior to AD 1700, depending on the immediate needs of the government, and lands and goods were more commonly taxed than income, which in the era before professionalized accounting was hard for the taxpayer to calculate and even harder for the tax collector to verify. In fact, a fixed national income tax of the sort on which the game’s concept of a “tax rate” seems to be vaguely modeled didn’t come to the United States until 1913. Many ancient societies — including ones as advanced as Egypt during its Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom epochs — never even developed currency at all. Even in the game Currency is an advance which you need to research; the cognitive dissonance inherent in earning coins for your treasury when your civilization lacks the concept of money is best just not thought about.

Let’s take a moment now to see if we can make a more worthwhile connection between real economic history and luxuries, that third category toward which you can devote your civilization’s economic resources. You’ll likely have to begin doing so only if and when your cities start to grow to truly enormous sizes, something that’s likely to happen only under the supercharged economy of a democracy. When all of the usual bread and circuses fail, putting resources into luxuries can maintain the delicate morale of your civilization, keeping your cities from lapsing into revolt. There’s an historical correspondence that actually does seem perceptive here; the economies of modern Western democracies, by far the most potent the world has ever known, are indeed driven almost entirely by a robust consumer market in houses and cars, computers and clothing. Yet it’s hard to know where to really go with Civilization‘s approach to luxuries beyond that abstract statement. At most, you might put 20 or 30 percent of your resources into them, leaving the rest to taxes and research, whereas in a modern developed democracy like the United States those proportions tend to be reversed.

Ironically, the real-world economic system to which Civilization‘s overall model hews closest is actually a centrally-planned communist economy, where all of a society’s resources are the property of the state — i.e., you — which decides how much to allocate to what. But Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley would presumably have run screaming from any such association — not to mention our friend Mr. Emrich, who would probably have had a conniption. It seems safe to say, then, that what we can learn from the Civilization economic model is indeed sharply limited, that most of it is there simply as a way of making a playable game.

Still, we might usefully ask whether there’s anything in the game that does seem like a clear-cut result of its designers’ attitudes toward real-world economics. We actually have seen some examples of that already in the economic effects that various systems of government have on your civilization, from the terrible performance of despotism to the supercharging effect of democracy. And there is one other area where Civilization stakes out some clear philosophical territory: in its attitude toward trade between civilizations, a subject that’s been much in the news in recent years in the West.

In the game, your civilization can reap tangible benefits from its contact with other civilizations in two ways. For one, you can use special units called caravans, which become available after you’ve researched the advance of Trade, to set up “trade routes” between your cities and those of other civilizations. Both then receive a direct boost to their economies, the magnitude of which depends on their distance from one another — farther is better — and their respective sizes. A single city can set up such mutually beneficial arrangements with up to five other cities, and see them continue as long as the cities in question remain in existence.

In addition to these arrangements, you can horse-trade advances directly with the leaders of other civilizations, giving your counterpart one of your advances in exchange for one you haven’t yet acquired. It’s also possible to take advances from other civilizations by conquering their cities or demanding tribute, but such hostile approaches have obvious limits to which a symbiotic trading relationship isn’t subject; fighting wars is expensive in terms of blood and treasure alike, and you’ll eventually run out of enemy cities to conquer. If, on the other hand, you can set up warm relationships with four or five other civilizations, you can positively rocket up the Advances Chart.

The game’s answer to the longstanding debate between free trade and protectionism — between, to put a broader framing on it, a welcoming versus an isolationist attitude toward the outside world — is thus clear: those civilizations which engage economically with the world around them benefit enormously and get to Alpha Centauri much faster. Such a position is very much line in line with the liberal-democratic theories of history that were being espoused by thinkers like Francis Fukuyama at the time Meier and Shelley were making the game — thinkers whose point of view Civilization unconsciously or knowingly adopts.

As has become par for the course by now, I believe that the position Civilization and Fukuyama alike take on this issue is quite well-supported by the evidence of history. To see proof, one doesn’t have to do much more than look at where the most fruitful early civilizations in history were born: near oceans, seas, and rivers. Egypt was, as the ancient historian Herodotus so famously put it, “the gift of the Nile”; Athens was born on the shores of the Mediterranean; Rome on the east bank of the wide and deep Tiber river. In ancient times, when overland travel was slow and difficult, waterways were the superhighways of their era, facilitating the exchange of goods, services, and — just as importantly — ideas over long distances. It’s thus impossible to imagine these ancient civilizations reaching the heights they did without this access to the outside world. Even today port cities are often microcosms of the sort of dynamic cultural churn that spurs civilizations to new heights. Not for nothing does every player of the game of Civilization want to found her first city next to the ocean or a river — or, if possible, next to both.

To better understand how these things work in practice, let’s return one final time to the dawn of history for a narrative of progress involving one of the greatest of all civilizations in terms of sheer longevity.

Egypt was far from the first civilization to spring up in the Fertile Crescent, that so-called “cradle of civilization.” The changing climate that forced the hunter-gatherers of the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys to begin to settle down and farm as early as 10,000 BC may not have forced the peoples roaming the lands near the Nile to do the same until as late as 4000 BC. Yet Egyptian civilization, once it took root, grew at a crazy pace, going from primitive hunter-gatherers to a culture that eclipsed all of its rivals in grandeur and sophistication in less than 1500 years. How did Egypt manage to advance so quickly? Well, there’s strong evidence that it did so largely by borrowing from the older, initially wiser civilizations to its east.

Writing is among the most pivotal advances for any young civilization; it allows the tallying of taxes and levies, the inventorying of goods, the efficient dissemination of decrees, the beginning of contracts and laws and census-taking. It was if anything even more important in Egypt than in other places, for it facilitated a system of strong central government that was extremely unusual in the world prior to the Enlightenment of many millennia later. (Ancient Egypt at its height was, in other words, a marked exception to the rule about local government being more important than national prior to the modern age.) Yet there’s a funny thing about Egypt’s famous system of hieroglyphs.

In nearby Sumer, almost certainly the very first civilization to develop writing, archaeologists have traced the gradual evolution of cuneiform writing by fits and starts over a period of many centuries. But in Egypt, by contrast, writing just kind of appears in the archaeological record, fully-formed and out of the blue, around 3000 BC. Now, it’s true that Egypt didn’t simply take the Sumerian writing system; the two use completely different sets of symbols. Yet many archaeologists believe that Egypt did take the idea of writing from Sumer, with whom they were actively trading by 3000 BC. With the example of a fully-formed vocabulary and grammar, all translated into a set of symbols, the actual implementation of the idea in the context of the Egyptian language was, one might say, just details.

How long might it have taken Egypt to make the conceptual leap that led to writing without the Sumerian example? Not soon enough, one suspects, to have built the Pyramids of Giza by 2500 BC. Further, we see other diverse systems of writing spring up all over the Mediterranean and Middle East at roughly the same time. Writing was an idea whose time had come, thanks to trading contacts. Trade meant that every new civilization wasn’t forced to reinvent every wheel for itself. It’s since become an axiom of history that an outward-facing civilization is synonymous with youth and innovation and vigorous growth, an inward-turning civilization synonymous with age and decadence and decrepit decline. It happened in Egypt; it happened in Greece; it happened in Rome.

But, you might say, the world has changed a lot since the heyday of Rome. Can this reality that ancient civilizations benefited from contact and trade with one another really be applied to something like the modern debate over free trade and globalization? It’s a fair point. To address it, let’s look at the progress of global free trade in times closer to our own.

In the game of Civilization, you won’t be able to set up a truly long-distance, globalized trading network with other continents until you’ve acquired the advance of Navigation, which brings with it the first ships that are capable of transporting your caravan units across large tracts of ocean. In real history, the first civilizations to acquire such things were those of Europe, in the late fifteenth century AD. Economists have come to call this period “The First Globalization.”

And, tellingly, they also call this period “The Great Divergence.” Prior to the arrival of ships capable of spanning the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, several regions of the world had been on a rough par with Europe in terms of wealth and economic development. In fact, at least one great non-European civilization — that of China — was actually ahead; roughly one-third of the entire world’s economic output came from China alone, outdistancing Europe by a considerable margin. But, once an outward-oriented Europe began to establish itself in the many less-developed regions of the world, all of that changed, as Europe surged forward to the leading role it would enjoy for the next several centuries.

How did the First Globalization lead to the Great Divergence? Consider: when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498, he found he could buy pepper there, where it was commonplace, for a song. He could then sell it back in Europe, where it was still something of a delicacy, for roughly 25 times what he had paid for it, all while still managing to undercut the domestic competition. Over the course of thousands of similar trading arrangements, much of the rest of the world came to supply Europe with the cheap raw materials which were eventually used to fuel the Industrial Revolution and to kick the narrative of progress into overdrive, making even tiny European nations like Portugal into deliriously rich and powerful entities on the world stage.

And what of the great competing civilization of China? As it happens, it might easily have been China instead of Europe that touched off the First Globalization and thereby separated itself from the pack of competing civilizations. By the early 1400s, Chinese shipbuilding had advanced enough that its ships were regularly crisscrossing the Indian Ocean between established trading outposts on the east coast of Africa. If the arts of Chinese shipbuilding and navigation had continued to advance apace, it couldn’t have been much longer until its ships crossed the Pacific to discover the Americas. How much different would world history have been if they had? Unfortunately for China, the empire’s imperial leaders, wary of supposedly corrupting outside influences, made a decision around 1450 to adopt an isolationist posture. Existing trans-oceanic trade routes were abandoned, and China retreated behind its Great Wall, leaving Europe to reap the benefits of global trade. By 1913, China’s share of the world’s economy had dropped to 4 percent. The most populous country in the world had become a stagnant backwater in economic terms. So, we can say that Europe’s adoption of an outward-facing posture just as China did the opposite at this critical juncture became one of the great difference-makers in world history.

We can already see in the events of the late fifteenth century the seeds of the great debate over globalization that rages as hotly as ever today. While it’s clear that the developed countries of Europe got a lot out of their trading relationships, it’s far less clear that the less-developed regions of the world benefited to anything like the same extent — or, for that matter, that they benefited at all.

This first era of globalization was the era of colonialism, when developed Europe freely exploited the non-developed world by toppling or co-opting whatever forms of government already existed among its new trading “partners.” The period brought a resurgence of the unholy practice of slavery, along with forced religious conversions, massacres, and the theft of entire continents’ worth of territory. Much later, over the course of the twentieth century, Europe gradually gave up most of its colonies, allowing the peoples of its former overseas possessions their ostensible freedom to build their own nations. Yet the fundamental power imbalances that characterized the colonial period have never gone away. Today the developing world of poor nations trades with the developed world of rich nations under the guise of being equal sovereign entities, but the former still feeds raw materials to the industrial economies of the latter — or, increasingly, developing industrial economies feed finished goods to the post-industrial knowledge economies of the ultra-developed West. Proponents of economic globalization argue that all of this is good for everyone concerned, that it lets each country do what it does best, and that the resulting rising economic tide lifts all their boats. And they argue persuasively that the economic interconnections globalization has brought to the world have been a major contributing factor to the unprecedented so-called “Long Peace” of the last three quarters of a century, in which wars between developed nations have not occurred at all and war in general has become much less frequent.

But skeptics of economic globalism have considerable data of their own to point to. In 1820, the richest country in the world on a per-capita basis was the Netherlands, with an inflation-adjusted average yearly income of $1838, while the poorest region of the world was Africa, with an average income of $415. In 2017, the Netherlands had an average income of $53,582, while the poorest country in the world for which data exists was in, you guessed it, Africa: it was the Central African Republic, with an average income of $681. The richest countries, in other words, have seen exponential economic growth over the last two centuries, while some of the poorest have barely moved at all. This pattern is by no means entirely consistent; some countries of Asia in particular, such as Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and Japan, have done well enough for themselves to join the upper echelon of highly-developed post-industrial economies. Yet it does seem clear that the club of rich nations has grown to depend on at least a certain quantity of nations remaining poor in order to keep down the prices of the raw materials and manufactured goods they buy from them. If the rising tide lifted these nations’ boats to equality with those of the rich, the asymmetries on which the whole world economic order runs today wouldn’t exist anymore. The very stated benefits of globalization carry within them the logic for keeping the poor nations’ boats from rising too high: if everyone has a rich, post-industrial economy, who’s going to do the world’s grunt work? This debate first really came to the fore in the 1990s, slightly after the game of Civilization, as anti-globalization became a rallying cry of much of the political left in the developed world, who pointed out the seemingly inherent contradictions in the idea of economic globalization as a universal force for good.

Do note that I referred to “economic globalization” there. We should do what we can to separate it from the related concepts of political globalization and cultural globalization, even as the trio can often seem hopelessly entangled in the real world. Still, political globalization, in the form of international bodies like the United Nations and the International Court of Justice, is usually if not always supported by leftist critics of economic globalization.

But cultural globalization is decried to almost an equal degree, being sometimes described as the “McDonaldization” of the world. Once-vibrant local cultures all over the world, goes the claim, are being buried under the weight of an homogenized global culture of consumption being driven largely from the United States. Kids in Africa who have never seen a baseball game rush out to buy the Yankees caps worn by the American rap stars they worship, while gangsters kill one another over Nike sneakers in the streets of China. Developing countries, the anti-globalists say, first get exploited to produce all this crap, then get the privilege of having it sold back to them in ways that further eviscerate their cultural pride.

And yet, as always with globalization, there’s also a flip side. A counter-argument might point out that at the end of the day people have a right to like what they like (personally, I have no idea why anyone would eat a McDonald’s hamburger, but tastes evidently vary), and that cultures have blended with and assimilated one another from the days when ancient Egypt traded with ancient Sumer. Young people in particular in the world of today have become crazily adept at juggling multiple cultures: getting married in a traditional Hindu ceremony on Sunday and then going to work in a smart Western business suit on Monday, listening to Beyoncé on their phone as they bike their way to sitar lessons. Further, the emergence of new forms of global culture, assisted by the magic of the Internet, have already fostered the sorts of global dialogs and global understandings that can help prevent wars; it’s very hard to demonize a culture which has produced some of your friends, or even just creative expressions you admire. As the younger generations who have grown up as members of a sort of global Internet-enabled youth culture take over the levers of power, perhaps they will become the vanguard of a more peaceful, post-nationalist world.

The debate about economic globalization, meanwhile, has shifted in some surprising ways in recent years. Once a cause associated primarily with the academic left, cosseted in their ivory towers, the anti-globalization impulse has now become a populist movement that has spread across the political spectrum in many developed countries of the West. Even more surprisingly, the populist debate has come to center not on globalization’s effect on the poor nations on the wrong side of the power equation but on those rich nations who would seem to be its clear-cut beneficiaries. In just the last couple of years as of this writing, blue-collar workers who feel bewildered and displaced by the sheer pace of an ever-accelerating narrative of progress in an ever more multicultural world were a driving force behind the Brexit vote in Britain and the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States. The understanding of globalization which drove both events was simplistic and confused — trade deficits are no more always a bad thing for any given country than is a national tax deficit — but the visceral anger behind them was powerful enough to shake the established Western world order more than any event since the World Trade Center attack of 2001. It should become more clear in the next decade or so whether, as I suspect, these movements represent a reactionary last gasp of the older generation before the next, more multicultural and internationalist younger generation takes over, or whether they really do herald a more fundamental shift in geopolitics.

As for the game of Civilization: to attempt to glean much more from its simple trading mechanisms than we already have would be to fall into the same trap that ensnared Alan Emrich. A skeptic of globalization might note that the game is written from the perspective of the developed world, and thus assumes that your civilization is among the privileged ranks for whom globalization on the whole has been — sorry, Brexiters and Trump voters! — a clear benefit. This is true even if the name of the civilization you happen to be playing is the Aztecs or the Zulus, peoples for whom globalization in the real world meant the literal end of their civilizations. As such examples prove, the real world is far more complicated than the game makes it appear. Perhaps the best lesson to take away — from the game as well as from the winners and arguable losers of globalization in our own history — is that it really does behoove a civilization to actively engage with the world. Because if it doesn’t, at some point the world will decide to engage with it.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K a Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, The End of History and the Last Man by Francis Fukuyama, Economics by Paul Samuelson, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt by Toby Wilkinson, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker, Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction by Robert C. Allen, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction by Manfred B. Steger, Taxation: A Very Short Introduction by Stephen Smith, and Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond.)