Democracy is like a raft. It never sinks, but, damn it, your feet are always in the water.

— Fisher Ames

What can we say about democracy, truly one of the most important ideas in human history? Well, we can say, for starters, that it’s yet another Greek word, a combination of “demos” — meaning the people or, less favorably, the mob — with “kratos,” meaning rule. Rule by the people, rule by the mob… the preferred translations have varied with the opinion of the translator.

The idea of democracy originated, as you might expect given the word’s etymology, in ancient Greece, where Plato detested it, Aristotle was ambivalent about it, and the citizens of Athens were intrigued enough to actually try it out for a while in its purest form: that of a government in which every significant decision is made through a direct vote of the people. Yet on the whole it was regarded as little more than an impractical ideal for many, many centuries, even as some countries, such as England, developed some mechanisms for sharing power between the monarch and elected or appointed representatives of other societal interests. It wasn’t until 1776 that a new country-to-be called the United States declared its intention to make a go of it as a full-blown representational democracy, thereby touching off the modern era of government, in which democracy has increasingly come to be seen as the only truly legitimate form of government in the world.

Like the Christianity that had done so much to lay the groundwork for its acceptance, democracy was a meme with such immediate, obvious mass appeal that it was well-nigh impossible to control once the world had a concrete example of it to look at in the form of the United States. Over the course of the nineteenth century, responding to the demands of their restive populations, remembering soberly what had happened to Louis XVI in France when he had tried to resist the democratic wave, many of the hidebound old monarchies of Europe found ways to democratize in part if not in total; in Britain, for example, about 40 percent of adult males were allowed to vote by 1884. When the drift toward democracy failed to prevent the carnage of World War I, and when that war was followed by a reactionary wave of despotic fascism, many questioned whether democracy was really all it had been cracked up to be. Yet even as the pundits doubted, the slow march of democracy continued; by 1930, almost all adult citizens of Britain, including women, were allowed to vote. By the time the game of Civilization was made near the end of the twentieth century, any doubts about democracy’s ethical supremacy and practical efficacy had been cast aside, at least in the developed West. In missives like Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History, it was once again being full-throatedly hailed as the natural endpoint of the whole history of human governance.

We may not wish to go as far as calling democracy the end of history, but there’s certainly plenty of historical data in its favor. There’s been an undeniable trend line from the end of the eighteenth century to today, in which more and more countries have become more and more democratic. And, equally importantly, over the last century or so virtually all of the most successful countries in terms of per-capita economic performance have been democracies. A few interrelated factors likely explain why this should be the case.

One of them is the reality that as societies and economies develop they inevitably become more and more complex, a confusing mosaic of competing and cooperating interests which seemingly only democracy is equipped to navigate. “Democracies permit participation and therefore feedback,” writes Francis Fukuyama.

Another factor is the way that democracies manage to subsume within them the seemingly competing virtues of stability and renewal. As anyone who’s observed the worldwide stock markets after one of President Donald Trump’s more unhinged tweets can attest, business in particular loves stability and hates the uncertainty that’s born of political change. Yet often change truly is necessary, and often an aged, rigid-thinking despot or monarch is the very last person equipped to push it through. An election every fixed number of years provides a country with the ability to put new blood in power whenever it’s needed, without the chaos of revolution.

The final factor is another reality disliked by despots everywhere: the reality that education and democracy go hand in hand. A successful economy requires an educated workforce, but an educated workforce has a disconcerting tendency to demand a greater role in civic life. Francis Fukuyama:

Economic development demonstrates to the slave the concept of mastery, as he discovers he can master nature through technology, and master himself as well through the discipline of work and education. As societies become better educated, slaves have the opportunity to become more conscious of the fact that they are slaves and would like to be masters, and to absorb the ideas of other slaves who have reflected on their condition of servitude. Education teaches them that they are human beings with dignity, and that they ought to struggle to have that dignity recognized.

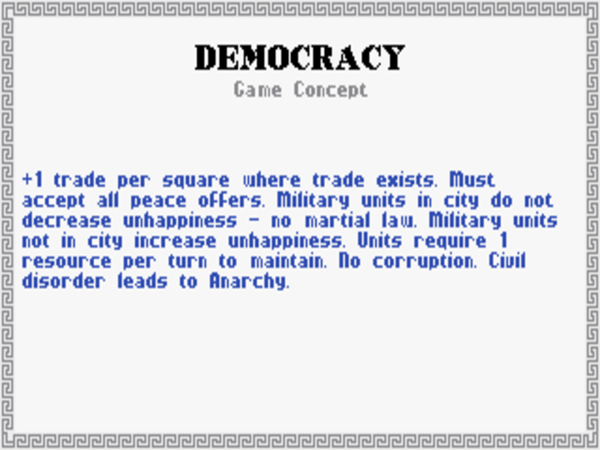

When making the game of Civilization, Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley clearly understood the longstanding relationship between a stable democracy and a strong economy — a relationship which is engendered by all of the factors I’ve just described. Switching your government to democracy in the game thus supercharges your civilization’s economic performance, dramatically increasing the number of “trade” units your cities collect.

But the game isn’t always so clear-sighted; the Civilopedia describes democracy as “fragile” in comparison to other forms of government. I would argue that in many ways just the opposite is the case. It’s true that democracies can be incredibly difficult to start in a country with little tradition of same, as the multiple false starts that we’ve seen in places like Russia and much of sub-Saharan Africa will attest. Yet once they’ve taken root they can be extremely difficult if not impossible to dislodge. Having, as we’ve already seen, the means of self-correction baked into them in a way that no other form of government does, mature democracies are surprisingly robust things. In fact, examples of mature, stable democracies falling back into autocracy simply don’t exist in history to date. [1]The collapsed democracies of places like Venezuela and Sri Lanka, which managed on paper to survive several decades before their downfall, could never be described as mature or stable, having been plagued throughout those decades with constant coup attempts and endemic corruption. Ditto Turkey, which has sadly embraced Putin-style sham democracy in the last few years after almost a century of intermittent crises, including earlier coups or military interventions in civilian government in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. Of course, we have to be wary of straying into the logical fallacy of simply defining any democracy which collapses as never having been stable to begin with. Still, I think the evidence, at least as of this writing, justifies the claim that a mature, stable democracy has never yet collapsed back into blatant authoritarianism. History would seem to indicate that, if a new democracy can survive thirty or forty years without coups or civil wars — long enough, one might say, for democracy to put down roots and become an inviolate cultural tradition — it can survive for the foreseeable future.

Ironically, Civilization portrays its dubious assertion of democratic “fragility” using methods that actually do feel true to history. The ease with which democracies can fall into unrest means that you must pay much closer attention to public opinion — taking the form of your population’s proportion of “unhappy” to “happy” citizens — than under any other system of government. Any democratic politician in the real world, forced to live and die by periodic opinion polls that take the form of elections, would no doubt sympathize with your plight. It’s particularly difficult in the game to prosecute a foreign war as a democracy, both because sending military units abroad sends your population’s morale into the toilet and because the game forces you to always accept peace overtures from your enemies as a matter of public policy.

In light of this last aspect of the game, the intersection of democracy and war in the real world merits digging into a bit further. Earlier in this series of articles, I wrote about the so-called “Long Peace” in which we’ve been living since the end of World War II, in which the great powers of the world have ceased to fight one another directly even when they find themselves at odds politically, and in which war in general has been on a marked decline in the world. I introduced theories about why that might be, such as the fear of nuclear annihilation and the emergence of global peacekeeping institutions like the United Nations. Well, another strong theory comes down to the advance of democracy. It’s long been an accepted rule among historians that mature, stable democracies simply don’t go to war with one another. Thus, as democracies multiply in the world, the possibilities for war decrease in rhythm, thanks to the incontrovertible logic of statistics. For this reason, some historians prefer to call the Long Peace the “Democratic Peace.”

Civilization reflects this democratic aversion to war through the draconian disadvantages that make its version of democracy, although the best government you can have in peacetime, the absolute worst you can have during war. As demonstrated not least by the United States’s many and varied military interventions since 1945, the game if anything overstates the case for democracy as force for peace. Yet, as I also noted in that earlier article, this crippling need the United States military now feels to make its wars, which are now covered by legions of journalists and shown every night on television, such clean affairs says much about its citizens’ unwillingness to accept the full, ugly toll of the country’s voluntary “police actions” and “liberations.”

But what of wars that have bigger stakes? Civilization‘s mechanics actually vastly understate the case for democracy here. They fail to account for the fact that, once the people of a democracy have firmly committed themselves to fighting an all-out war, history gives us little reason to believe that they can’t prosecute that war as well as they could under any other form of government. In reality, the strong economies that usually accompany democracies are an immense military advantage; the staggering economic might of the United States is undoubtedly the primary reason the Allied Powers were able to reverse the tide of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan and win World War II in, all things considered, fairly short order.

There’s one final element of the game of Civilization‘s take on democracy that merits discussion: its complete elimination of corruption. Under other forms of government, the corruption mechanic causes cities other than your capital to lose a portion of their economic potential to this most insidious of social forces, with how much they lose depending on their distance from your capital. You can combat it only by building courthouses in some of your non-capital cities; they’re fairly expensive in both purchase and maintenance costs, but reduce corruption within their sphere of influence. Or you can eliminate all corruption at a stroke by making your civilization a democracy.

At first blush, this sounds both hilarious and breathtakingly naive. It would seem to indicate, as Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich note in Civilization: or Rome on 640K a Day, that Meier and Shelley’s research into the history of democracy neglected such icons of its American version as Tammany Hall and Teapot Dome, not to mention Watergate. Yet when we really stop to consider, we find that this seemingly naive mechanic may actually be one of the most historically and sociologically perceptive in the whole game.

If you’ve ever traveled independently in a non-democratic, less-developed country, you’ve likely seen a culture of corruption first-hand. Personal business there is done through wads of cash passed from pocket to pocket, and every good and service tends to have a price that fluctuates from customer to customer, based on a reading of what that particular market will bear. Most obviously from your foreigner’s perspective, there are tourist prices and native prices.

The asymmetries that lead to the rampant “cheating” of foreign customers aren’t hard to understand. You can pay twenty times the going rate for that bottle of soda and never think about it again, while your shopkeeper can use the extra money to put some meat on his family’s table tonight; the money is far more important to him than it is to you because you are rich and he is poor. This reality will probably cause you to give up quibbling about petty (to you) sums in fairly short order. But the mindset behind it is deadly to a country’s economic prospects — not least to its tax base, which could otherwise be used to institute the programs of education and infrastructure that can lead a country out of the cycle of poverty. High levels of corruption are comprehensively devastating to a country’s economy — witness, to take my favorite whipping boy again, Vladimir Putin’s thoroughly corrupt Russia with its economy 7 percent the size of the United States’s — while a relative lack of corruption allows it to thrive.

As it happens, corruption levels across government, business, and personal life in the real world correlate incredibly well with the presence or absence of democracy. When we look at the ten least-corrupt countries in the world according to the Corruption Perceptions Index for 2017, we find that nine of them are among the nineteen countries that are given the gold star of Full Democracy by The Economist‘s latest Democracy Index. (Singapore, the sole exception among the top ten, is classified as a Hybrid System.) Meanwhile none of the ten most-corrupt countries qualify as Full or even Flawed Democracies, with seven of the ten classified as full-on authoritarian states. When we further consider that levels of corruption are inversely correlated to a country’s overall economic performance, we add to our emerging picture of just why democracy has accrued so much wealth and power to the developed West since the beginning of the great American experiment back in 1776.

And there may be yet another, more subtle inverse linkage between democracy and corruption. As I noted at the beginning of this pair of articles on Civilization‘s systems of government, I’ve tried to arrange them in an order that reflects the relative stress they place on the individual leader versus the institutions of leadership. Thus the despotic state and the monarchy are so defined by their leaders as to be almost indistinguishable as entities apart from them, while the republic and the democracy mark the emergence of the concept of the state as a sovereign entity unto itself, with its individual leaders mere stewards of a legacy greater than themselves. I don’t believe that this shift in thinking is reflected only in a country’s leadership; it rather extends right through its society. A culture of corruption emphasizes personal, transactional relationships, while its opposite places faith in strong, stable institutions with a lifespan that will hopefully transcend that of the people who staff them at any given time.

So, let’s turn back now to the game’s once-laughable assertion that democracy eliminates corruption, which now seems at least somewhat less laughable. It is, of course, an abstraction at best; a country can no more eliminate corruption than it can eliminate poverty or terrorism (to name a couple of other non-proper nouns on which our politicians like to declare war). Yet a country can sharply de-incentivize it by bringing it to light when it does appear, and by shaming and punishing those who engage in it.

Given the times in which I’m writing this article, I do understand how strange it may sound to argue that Civilization‘s optimistic take on corruption in democracy is at bottom a correct one. Just a couple of years ago in the Full Democracy of Germany, the twelfth least-corrupt country on the planet according to the Corruption Perceptions Index, executives in the biggest of the country’s auto manufacturers were shown to have concocted a despicable scheme to cheat emissions standards worldwide in the name of profit, ignoring the environmental consequences to future generations. And as I write these words the Trump administration in the Flawed Democracy of the United States, sixteenth least-corrupt country on the planet, has so many ongoing scandals that the newspapers literally don’t have enough reporters to cover them all. But the fact that we know about these scandals — that we’re reading about them and arguing about them and in some cases taking to the streets to protest them — is proof that liberal democracy is still working rather than the opposite. Compare the anger and outrage manifested by opponents and defenders alike of Donald Trump with the sullen, defeated acceptance of an oligarchical culture of corruption that’s so prevalent in Russia.

Which isn’t to say that democracy is without its disadvantages. From the moment the idea of rule by the people was first broached in ancient Athens, it’s had fierce critics who have regarded it as inherently dangerous. Setting aside the despots and monarchs who have a vested interest in other philosophies of government, thoughtful criticisms of democracy have almost always boiled down to the single question of whether the great unwashed masses can really be trusted to rule.

Plato was the first of the great democratic skeptics, describing it as the victory of opinion over knowledge. Many of the great figures of American history have ironically taken his point of view to heart, showing considerable ambivalence toward this supposedly greatest of American virtues. The framers of the Constitution twisted themselves into knots over a potential tyranny of the ignorant over the educated, and built into it machinations to hopefully prevent such a scenario — machinations that still determine the direction of American politics to this day. (The electoral college which has awarded the presidency twice in the course of the last five elections to someone who didn’t win the popular vote was among the results of the Founding Fathers’ terror of the masses; in amplifying the votes of the country’s generally less-educated rural areas in recent years, it has arguably had exactly the opposite of its intended effect). Even the great progressive justice Oliver Wendell Holmes could disparage democracy as merely “what the crowd wants.”

In the cottage industry of American political punditry as well, there’s a long tradition of lamenting the failure of the working class to vote their own self-interest on economic matters, of earnest hand-wringing over the way they supposedly fall prey instead to demagogic appeals to cultural identity and religion. One of the best-selling American nonfiction books of 2011 was The Myth of the Rational Voter, which deployed reams of sociological data to reveal that (gasp!) the ballot-box choices of most people have more to do with emotion, prejudice, and rigid ideology than rationality or enlightened self-interest. Recently, such concerns have been given new urgency among the intellectual elite all over the West by events like the election of Donald Trump in the United States, the Brexit vote in Britain, and the wave of populist political victories and near-victories across Europe — all movements that found the bulk of their support among the less educated, a fact that was lost on said elite not at all.

Back in 1872, the British journalist Walter Bagehot wrote of the dangers of rampant democracy in the midst of another conflicted time in British history, as the voting franchise was being gradually expanded through a series of controversial so-called “Reform Bills.” His writing rings in eerie accord with the similar commentaries from our own time, warning as it does of “the supremacy of ignorance over instruction and of numbers [of voters] over knowledge”:

In plain English, what I fear is that both our political parties will bid for the support of the working man; that both of them will promise to do as he likes if he will only tell them what it is. I can conceive of nothing more corrupting or worse for a set of poor ignorant people than that two combinations of well-taught and rich men should constantly defer to their decision, and compete for the office of executing it. “Vox populi” [“the voice of the people”] will be “Vox diaboli” [“the voice of the devil”] if it is worked in that manner.

Consider again my etymology of the word “democracy” from the beginning of this article. “Demos” in the Greek can variously mean, as I explained, the people or the mob. It’s the latter of these that is instinctively feared, by no means entirely without justification, by democratic skeptics like the ones whose views I’ve just been describing. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt defines the People as a constructive force, citizens acting in good faith to improve their country’s society, while the Mob is a destructive force, citizens acting out of hate and fear against rather than for the society from which they feel themselves excluded. We often hear it suggested today that we may have reached the tipping point where the People become a Mob in many places in the West. We hear frequently that the typical Brexit or Trump voter feels so disenfranchised and excluded that she just doesn’t care anymore, that she wants to throw Molotov cocktails into the middle of the elites’ most sacred institutions and watch them burn — that she wants to blow up the entire postwar world order that progressives like me believe have kept us safe and prosperous for all these decades.

I can’t deny that the sentiment exists, sometimes even with good reason; modern democracies all remain to a greater or lesser degree flawed creations in terms of equality, opportunity, and inclusivity. I will, however, offer three counter-arguments to the Mob theory of democracy — one drawing from history, one from practicality, and one from a thing that seems in short supply these days, good old idealistic humanism.

My historical argument is that democracies are often messy, chaotic things, but, once again — and this really can’t be emphasized enough — a mature, stable democracy has never, ever collapsed back into a more retrograde system of government. If it were to happen to a democracy as mature and stable as the United States, as is so often suggested by alarmists in the Age of Trump, it would be one of the more shockingly unprecedented events in all of history. As things stand today, there’s little reason to believe that the institutions of democracy won’t survive President Donald Trump, as they have 44 other good, bad, and indifferent presidents before him. Ditto with respect to many of the other reactionary populist waves in other developed democracies.

My practical argument is the fact that, while democracies sometimes go down spectacularly misguided paths at the behest of their citizenry, they’re also far better at self-correcting than any other form of government. The media in the United States has made much of the people who were able to justify voting for Donald Trump in 2016 after having voted for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012. It’s become fashionable on this basis to question whether the ebbing of racial animus the latter’s election had seemed to represent was all an illusion. Yet there’s grounds for hope as well as dismay there for the current president’s opponents — grounds for hope in the knowledge that the pendulum can swing back in the other direction just as quickly. The anonymity of the voting booth means that people have the luxury of changing their minds entirely with the flick of a pen, without having to justify their choice to anyone, without losing face or appearing weak. Many an autocratic despot or monarch has doubtless dreamed of the same luxury. This unique self-correcting quality of democracy does much to explain why this form of government that the Civilopedia describes as so “fragile” is actually so amazingly resilient.

Finally, my argument from principle comes from the same idealistic place as those famous opening paragraphs of the American Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”). The Enlightenment philosophy that led to that document said, for the first time in the history of the world, that every man was or ought to be master of his own life. If we believe wholeheartedly in these metaphysical principles, we must believe as well that even a profoundly misguided democracy is superior to Plato’s beloved autocracy — even an autocracy under a “philosopher king” who benevolently makes all the best choices for the good of his country’s benighted citizens. For rule by the people is itself the greatest good, and one which no philosopher king can ever provide. Perhaps the best way to convert a Mob back into a People is to let them have their demagogues. When it doesn’t work out, they can just vote them out again come next election and try something else. What other form of government can make that claim?

Most people in the West during most of the second half of the twentieth century would agree that the overarching historical question of their times was whether the world’s future lay with democracy or communism. This was, after all, the question over which the Cold War was being fought (or, if you prefer, not being fought).

For someone studying the period from afar, however, the whole formulation is confusing from the get-go. Democracy has always been seen as a system of government, while communism, in theory anyway, has more to do with economics. In fact, the notion of a “communist democracy,” oxymoronic as it may sound to Western sensibilities, is by no means incompatible with communist theory as articulated by Karl Marx. Plenty of communist states once claimed to be exactly that, such as the German Democratic Republic — better known as East Germany. It’s for this reason that, while people in the West spoke of a Cold War between the supposed political ideologies of communism and democracy, people in the Soviet sphere preferred to talk of a conflict between the economic ideologies of communism and capitalism. And yet accepting the latter’s way of framing the conflict is giving twentieth-century communism far too much credit — as is, needless to say, accepting communism’s claim to have fostered democracies. By the time the Cold War got going in earnest, communism in practice was already a cynical lie.

This divide between communism as it exists in the works of Karl Marx and communism as it has existed in the real world haunts every discussion of the subject. We’ll try to pull theory and practice apart by looking first at Marx’s rosy nineteenth-century vision of a classless society of the future, then turning to the ugly reality of communism in the twentieth century.

One thing that makes communism unique among the systems of government we’ve examined thus far is how very recent it is. While it has roots in Enlightenment thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier, in its complete form it’s thoroughly a product of the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. Observing the world around him, Karl Marx divided society in the new industrial age into two groups. There were the “bourgeoisie,” a French word meaning literally “those who live in a borough,” or more simply “city dwellers”; these people owned the means of industrial production. And then there were the “proletariat,” a Latin word meaning literally “without property”; these people worked the means of production. Casting his eye further back, Marx articulated a view of all of human history as marked by similar dualities of class; during the Middle Ages, for instance, the fundamental divide was between the aristocrats who owned the land which was that era’s wellspring of wealth and the peasants who worked it. “The history of all hitherto existing societies,” he wrote, “is the history of class struggles.” As I mentioned in a previous article, his economic theory of history divided it into six phases: pre-civilized “primitive communism,” the “slave society” (i.e., despotism), feudalism (i.e., monarchy), pure laissez-faire capitalism (the phase the richest and most developed countries were in at the time he wrote), socialism (a mixed economy, not all that different from most of the developed democracies of today), and mature communism. Importantly, Marx believed that the world had to work through these phases in order, each one laying the groundwork for what would follow.

But, falling victim perhaps to a tendency that has dogged many great theorists of history, Marx saw his own times’ capitalist phase as different from all those that had come before in one important respect. Previously, class conflicts had been between the old elite and a new would-be elite that sought to wrest power from them — most recently, the landed gentry versus the new capitalist class of factory owners. But now, with the industrial age in full swing, he believed the next big struggles would be between the bourgeois elites and the proletarian masses as a whole. The proletariat would eventually win those struggles, resulting in a new era of true equality and majority rule. (Here, the eagerness of so many of the later communist states to label themselves democracies starts to become more clear.)

In light of what would follow in the name of Karl Marx, it’s all too easy to overlook the fact that he didn’t see himself as the agent which would bring about this new era; his communism was a description of what would happen in the future rather than a prescription for what should happen. Many of the direct calls to action in 1848’s The Communist Manifesto, by far his most rabble-rousing document, would ironically be universally embraced by the liberal democracies which would become the ideological enemy of communism in the century to come: things such as a progressive income tax, the abolition of child labor, and a basic taxpayer-funded education for everyone. The literary project he considered his most important life’s work, the famously dense three volumes of Capital, are, as the name would indicate, almost entirely concerned with capitalism and its discontents as Marx understood them to already exist, saying almost nothing about the communist future. Written later in his life and thus reflecting a more mature form of his philosophy, Capital shies away from even such calls to action as are found in The Communist Manifesto, saying again and again that the contradictions inherent in capitalism itself will inevitably bring it down when the time is right.

By this point in this life, Marx had become a thoroughgoing historical determinist, and was deeply wary of those who would use his theories to justify premature revolutions of the proletariat. Even The Communist Manifesto‘s calls to action had been intended not to force the onset of the last phase of history — communism — but to prod the world toward the penultimate phase of socialism. True communism, Marx believed, was still a long, long way off. Not least because he wrote so many more words about capitalism than he did about communism, Marx’s vision of the latter can be surprisingly vague for what would later become the ostensible blueprint for dozens upon dozens of governments, including those of two of the three biggest nations on the planet.

With this very basic understanding of Marxist theory, we can begin to understand the intellectual rot that lay at the heart of communism as it was actually implemented in the twentieth century. Russia in 1917 hadn’t even made it to Marx’s fourth phase of industrialized capitalism; as an agrarian economy, more feudal than capitalist, it was still mired in the third phase of history. Yet Vladimir Lenin proposed to leapfrog both of the intervening phases and take it straight to communism — something Marx had explicitly stated was not possible. Similarly ignoring Marx’s description of the transition to communism as a popular revolution of the people, Lenin’s approach hearkened back to Plato’s philosopher kings; he stated that he and his secretive cronies represented the only ones qualified to manage the transition. “It is an irony of history,” remarks historian Leslie Holmes dryly, “that parties committed to the eventual emergence of highly egalitarian societies were in many ways among the most elitist in the world.”

When Lenin ordered the cold-blooded murder of Czar Nicholas II and his entire family, he sketched the blueprint of communism’s practical future as little more than amoral despotism hiding behind a facade of Marxist rhetoric. And when capitalist systems all over the world didn’t collapse in the wake of the Russian Revolution, as he had so confidently predicted, there was never a question of saying, “Well, that’s that then!” and moving on. One of the most repressive governments in history was now firmly entrenched, and it wouldn’t give up power easily. “Socialism in One Country” became Josef Stalin’s slogan, as nationalism became an essential component of the new communism, again in direct contradiction to Marx’s theory of a new world order of classless equality. The guns and tanks parading through Red Square every May Day were a yearly affront to everything Marx had written.

Still, communist governments did manage some impressive achievements. Universal free healthcare, still a pipe dream throughout the developed West at the time, was achieved in the new Soviet Union in the 1920s. Right through the end of the Cold War, average life expectancy and infant-mortality rates weren’t notably worse in most communist countries than they were in Western democracies. Their educational systems as well were often competitive with those in the West, if sometimes emphasizing rote learning over critical thinking to a disturbing degree. Illiteracy was virtually nonexistent behind the Iron Curtain, and fluency in multiple languages was at least as commonplace as in Western Europe. Women were not just encouraged but expected to join the workforce, and were given a degree of equality that many of their counterparts in the West could only envy. The first decade or even in some cases several decades after the transition to communism would often bring an economic boom, as women entered the workforce for the first time and aged infrastructures were wrenched toward modernity, arguably at a much faster pace than could have been managed under a government more concerned about the individual rights of its citizens. Under these centrally planned economies, unemployment and the pain it can cause were literally unknown, as was homelessness. In countries where cars were still a luxury reserved for the more equal among the equal, public transport too was often surprisingly modern and effective.

In time, however, economic stagnation inevitably set in. Corruption in the planning departments — the root of the oligarchical system that still holds sway in the Russia of today — caused some industries to be favored over others with no regard to actual needs; the growing complexity of a modernizing economy overwhelmed the planners; a lack of personal incentive led to a paucity of innovation; prices and demand seemed to have no relation to one another, distorting the economy from top to bottom; the quality of consumer goods remained notoriously terrible. By the late 1970s, the Soviet Union, possessed of some of the richest farmland in the world, was struggling and failing just to feed itself, relying on annual imports of millions of tons of wheat and other raw foodstuffs. The very idea of the shambling monstrosity that was the Soviet economy competing with the emerging post-industrial knowledge economies of the West, which placed a premium on the sort of rampant innovation that can only be born of free press, free speech, and free markets, had become laughable. Francis Fukuyama:

The failure of central planning in the final analysis is related to the problem of technological innovation. Scientific inquiry proceeds best in an atmosphere of freedom, where people are permitted to think and communicate freely, and more importantly where they are rewarded for innovation. The Soviet Union and China both promoted scientific inquiry, particularly in “safe” areas of basic or theoretical research, and created material incentives to stimulate innovation in certain sectors like aerospace and weapons design. But modern economies must innovate across the board, not only in hi-tech fields but in more prosaic areas like the marketing of hamburgers and the creation of new types of insurance. While the Soviet state could pamper its nuclear physicists, it didn’t have much left over for the designers of television sets, which exploded with some regularity, or for those who might aspire to market new products to new consumers, a completely non-existent field in the USSR and China.

Marx had dreamed of a world where everyone worked just four hours per day to contribute her share of the necessities of life to the collective, leaving the rest of her time free to pursue hobbies and creative endeavors. Communism in practice did manage to get half of that equation right; few people put in more than four honest hours of labor per day. (As a popular joke said, “they pretend to pay me and I pretend to work.”) But these sad, ugly gray societies hardly encouraged a fulfilling personal life, given that the tools for hobbies were almost impossible to come by and so many forms of creative expression could land you in jail.

If there’s one adjective I associate more than any other with the communist experiments of the twentieth century, it’s “corrupt.” Born of a self-serving corruption of Marx’s already questionable theories, their economies functioned so badly that corruption on low and on high, of forms small and large, was the only way they could muddle through at all. Just as the various national communist parties were vipers’ nests of intrigue and backstabbing in the name of very non-communist personal ambitions, ordinary citizens had to rely on an extensive black market that lived outside the planned economy in order to simply survive.

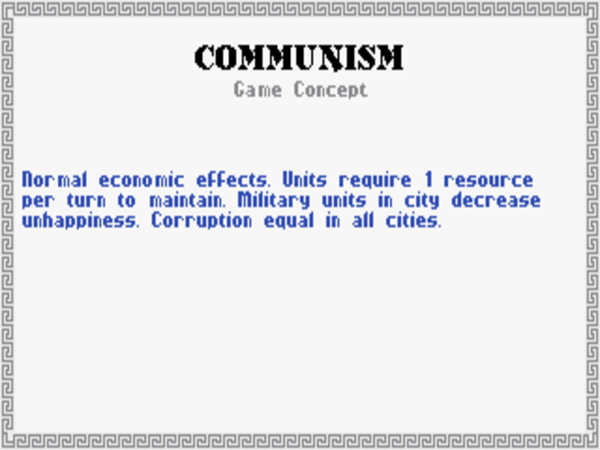

So, in examining the game of Civilization‘s take on communism, one first has to ask which version of same is being modeled, the idealistic theory or the corrupt reality. It turns out pretty obviously to be the reality of communism as it was actually practiced in the twentieth century. In another of their crazily insightful translations of history to code, Meier and Shelley made communism’s effect on the game’s mechanic of corruption its defining attribute. A communist economy in the game performs up to the same mediocre baseline standard as a monarchy — which is probably being generous, on the whole. Yet it has the one important difference that economy-draining corruption, rather than increasing in cities located further from your capital, is uniform across the entirety of your civilization. While the utility of this is highly debatable in game terms, it’s rather brilliant and kind of hilarious as a reflection of the way that corruption and communism have always been so inseparable from one another — essential to one another, one might even say — in the real world. After all, when your economy runs on corruption, you need to make sure you have it everywhere.

For all that history since the original Civilization was made has had plenty of troubling aspects, it hasn’t seen any resurgence of communism; even Russia hasn’t regressed quite that far. The new China, while still ruled by a cabal who label themselves the Communist Party, gives no more than occasional lip service to Chairman Mao, having long since become something new to history: a joining of authoritarianism and capitalism that’s more interested in doing business with the West than fomenting revolutions there, and has been far more successful at it than anyone could have expected, enough to challenge some of the conventional wisdom that democracy is required to manage a truly thriving economy. (I’ll turn back to the situation in China and ask what it might mean in the last article of this series.) Meanwhile the last remaining hard-line communist states are creaky old relics from another era, just waiting to take their place in hipster living rooms between vinyl record albums and lava lamps; a place like North Korea would almost be kitschy if its chubby man-child of a leader wasn’t killing and torturing so many of his own people and threatening the world with nuclear war.

When those last remaining old-school communist regimes finally collapse in one way or another, will that be that for Karl Marx as well? Probably not. There are still Marxists among us, many of whom say that the real, deterministic communist revolution is still ahead of us, who claim that the communism of the twentieth century was all a misguided and tragic false start, an attempt to force upon history what history was not yet ready for. They find grist for their mill in the fact that so many of the most progressive democracies in the world have embraced socialism, providing for their citizens much of what Marx asked for in The Communist Manifesto. If this vanguard has thus reached the fifth phase of history, can the sixth and final be far behind? We shall see. In the meantime, though, liberal democracy continues to provide something communism has never yet been able to: a practical, functional framework for a healthy economy and a healthy government right here and now, in the world in which we actually live.

I couldn’t conclude this survey without saying something about anarchy, Civilization‘s least desirable system of government — or, in this case, system of non-government. You fall into it only as a transitional phase between two other forms of government, or if you let your population under a democracy get too unhappy. Anarchy is, as the Civilopedia says, “a breakdown in government” that brings “panic, disruption, waste, and destruction.” It’s comprehensively devastating to your economy; you want to spend as little time in anarchy as you possibly can. And that, it would seem, is just about all there is to say about it.

Or is it? It’s worth noting that the related word “anarchism” in the context of government has another meaning that isn’t acknowledged by the game, one born from many of the same patterns of thought that spawned Karl Marx’s communism. Anarchism’s version of Marx could be said to be one Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who in 1840 applied what had hitherto been a pejorative term to a new, positive vision of social organization characterized not by yet another new system of government but by government’s absence. Community norms, working in tandem with the natural human desire to be accepted and respected, could according to the anarchists replace government entirely. By 1905, they had earned themselves an entry in the Encyclopædia Britannica:

[Anarchism is] the name given to a principle or theory of life and conduct under which society is conceived without government — harmony in such a society being obtained, not by submission to law, or by obedience to any authority, but by free agreements, concluded between the various groups, territorial and professional, freely constituted for the sake of production and consumption, as also for the satisfaction of the infinite variety of needs and aspirations of a civilised being.

As a radical ideology advocating a classless society, anarchism has often seemed to walk hand in hand with communism. As an ideology advocating the absolute supremacy of individual freedom, it’s sometimes seemed most at home in right-wing libertarian circles. Yet its proponents insist it to be dramatically different from either of these philosophies, as described by the American anarchist activist and journalist Dwight Macdonald in 1957:

The revolutionary alternative to the status quo today is not collectivised property administered by a “workers’ state,” whatever that means, but some kind of anarchist decentralisation that will break up mass society into small communities where individuals can live together as variegated human beings instead of as impersonal units in the mass sum. The shallowness of the New Deal and the British Labour Party’s postwar regime is shown by their failure to improve any of the important things in people’s lives — the actual relationships on the job, the way they spend their leisure, and child-rearing and sex and art. It is mass living that vitiates all these today, and the State that holds together the status quo. Marxism glorifies “the masses” and endorses the State [the latter is not quite true in terms of Marx’s original theories, as we’ve seen]. Anarchism leads back to the individual and the community, which is “impractical” but necessary — that is to say, it is revolutionary.

As Macdonald tacitly admits, it’s always been difficult to fully grasp how anarchism would work in theory, much less in practice; if you’ve always felt that communism is too practical a political ideology, anarchism is the radical politics for you. Its history has been one of constant defeat — or rather of never even getting started — but it never seems to entirely go away. Like Rousseau’s vision of the “noble savage,” it will always have a certain attraction in a world that only continues to get more complicated, in societies that continue to remove themselves further and further from what feels to some like their natural wellspring. For this reason, we’ll have occasion to revisit some anarchist ideas again in the last article of this series.

What, then, should we say in conclusion about Civilization and government? The game has often been criticized for pointing you toward one type of government — democracy — as by far the best for developing your civilization all the way to Alpha Centauri. That bias is certainly present in the game, but it’s hard for me to get as exercised about it as some simply because I’m not at all sure it isn’t also present in history. At least if we define progress in the same terms as Civilization, democracy has proved itself to be more than just an airy-fairy ideal; it’s the most effective means for organizing a society which we’ve yet come up with.

Appeals to principle aside, the most compelling argument for democracy has long been the simple fact that it works, that it’s better than any other form of government at creating prosperous, peaceful countries where, as our old friend Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel would put it, the most people have the most chance to fulfill their individual thymos. Tellingly, many of the most convincing paeans to democracy tend to come in the form of backhanded compliments. “Democracy is the worst form of government,” famously said Winston Churchill, “except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” Or, as the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr wrote, “Man’s inclination to justice makes democracy possible, but man’s capacity for injustice makes it necessary.” Make no mistake: democracy is a messy business. But history tells us that it really does work.

None of this is to say that you should be sanguine about your democracy’s future, assuming you’re lucky enough to live in one. Like videogames, democracy is an interactive medium. Protests and bitter arguments are a sign that it’s working, not the opposite. So, go protest and argue and all the rest, but remember as you do so that this too — whatever this happens to be — shall pass. And, at least if history is any guide, democracy shall live on after it does.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K a Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, The End of History and the Last Man by Francis Fukuyama, The Republic by Plato, Politics by Aristotle, Plough, Sword, and Book: The Structure of Human History by Ernest Gellner, Aristocracy: A Very Short Introduction by William Doyle, Democracy: A Very Short Introduction by Bernard Crick, Plato: A Very Short Introduction by Julia Annas, Political Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction by David Miller, The Myth of the Rational Voter by Bryan Caplan, Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction by Colin Ward, Communism: A Very Short Introduction by Leslie Holmes, Corruption: A Very Short Introduction by Leslie Holmes, The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Capital by Karl Marx, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined by Steven Pinker, What’s the Matter with Kansas: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America by Thomas Frank, The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The collapsed democracies of places like Venezuela and Sri Lanka, which managed on paper to survive several decades before their downfall, could never be described as mature or stable, having been plagued throughout those decades with constant coup attempts and endemic corruption. Ditto Turkey, which has sadly embraced Putin-style sham democracy in the last few years after almost a century of intermittent crises, including earlier coups or military interventions in civilian government in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. Of course, we have to be wary of straying into the logical fallacy of simply defining any democracy which collapses as never having been stable to begin with. Still, I think the evidence, at least as of this writing, justifies the claim that a mature, stable democracy has never yet collapsed back into blatant authoritarianism. |

|---|