If there was ever any doubt inside Origin Systems that Chris Roberts’s Wing Commander was destined to join Ultima as the company’s second great franchise, it was banished the moment the first game in the new series was released on September 26, 1990, and promptly sold by some accounts 100,000 copies in its first month on the market. Previously known as a maker of highly demanding CRPGs that were devoured by an exclusive audience of loyalists, Origin was suddenly the proud publisher of the game that absolutely everybody was talking about, regardless of what genre they usually favored. It was a strange turn of events, one that surprised Origin almost as much as it did the rest of their industry. Nevertheless, the company wouldn’t be shy about exploiting the buzz.

The first dribble in what would become a flood of additional Wing Commander product was born out of a planned “special edition” of the original game, to be sold only via direct mail order. Each numbered copy of the special edition was to be signed by Roberts and would include a baseball cap sporting the Wing Commander logo. To sweeten the deal, Roberts proposed that they also pull together some of the missions and spaceships lying around the office that hadn’t made the cut for the original game, string some story bits between them using existing tools and graphic assets, and throw that into the special-edition box as well.

But the commercial potential for the “mission disk” just kept growing as customers bought the original game, churned through the forty or so missions included therein, and came clamoring for more. Roberts, for one, was certain that mission disks should be cranked out in quantity and made available as widely as possible, likening them to all of the “adventure modules” he had purchased for tabletop Dungeons & Dragons as a kid. And so the profile of the so-called Secret Missions project kept growing, becoming first a standalone product available by direct order from Origin, and then a regular boxed product that was sold at retail, just like all their other games. “When I make the decision to purchase a product,” Roberts noted in his commonsense way, “I want to go to the store and buy it immediately. I don’t want to make a phone call and wait for someone to ship it to me.”

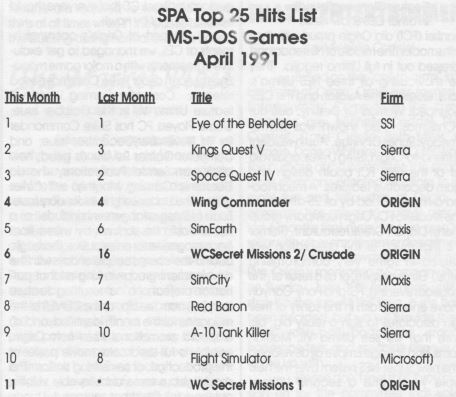

The add-on disk’s mission design wasn’t as good as that of the original game, which had already done a pretty good job of digging all of the potential out of the space-combat engine’s fairly limited bag of tricks. With no way of making the missions more interesting, the add-on settled for making them more difficult, throwing well-nigh absurd quantities of enemy spacecraft at the player. But it didn’t matter: players ate it up and kept right on begging for more. Origin obliged them again with Secret Missions 2, a somewhat more impressive outing that employed the engine which was in development for a standalone Wing Commander II, and was thereby able to add at least a few new wrinkles to the mission formula along with a more developed plot.

It was Wing Commander II itself, however, that everyone — not least among them Origin’s accountants — was really waiting for. Origin hoped to get the sequel out by June of 1991, just nine months after the first game. Chris Roberts, now installed as Origin’s “Director of New Technologies,” had been placed in charge of developing a true next-generation engine from scratch for use in the eventual Wing Commander III, and thus had a limited role in this interim step. Day-to-day responsibility for Wing Commander II passed into the hands of its “director” Stephen Beeman, [1]Stephen Beeman now lives as the woman Siobhan Beeman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. who had just finished filling the same role on Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire.

Beeman’s team of coders improved the space-combat engine in welcome ways. They properly accounted for the speed of the computer running the game, thus mostly fixing the speed issues which have dogged the first Wing Commander to this day. They added an innovative layer of adaptive artificial intelligence on the part of enemy ships, so that if the player flew and shot better the enemy did as well and vice versa, in an effort to remedy one of the primary complaints players had made about the Secret Missions disks in particular: that too many of the missions were just too darn hard. And they also created a whole new slate of ships to fight and to fly; most notable among them was the Broadsword, a lumbering torpedo bomber of a spaceship with rear- and side-facing gun turrets which the player could jump into and control.

Wing Commander II‘s most obvious new gameplay wrinkle is the Broadsword torpedo bomber, in which you can control gun turrets that shoot to the sides and behind. But it doesn’t work out all that well because your ship just keeps flying straight ahead, a clay pigeon for the Kilrathi, while you’re busy in the turret. I tend to ignore the existence of the turrets, and I suspect I’m not alone.

With Wing Commander II, Origin’s artists began using Autodesk 3D Studio. Jake Rodgers, the first 3D artist they hired to work with the new tool, had learned how to do so at an architecture firm. “After talking with Origin, I decided that creating spaceships sounded a lot more interesting than working on buildings,” he remembers. The actual game engine remained only pseudo-3D, but Rodgers and the artists he trained were able to use 3D Studio to make the sprites which represented the ships more detailed than ever, both in the game proper and in some very impressive animated cut scenes. The 3D revolution that was destined to have as huge an impact on the aesthetics of games as it would on the way they played was still a couple of years away from starting in earnest, but with the arrival of 3D Studio in Origin’s toolbox the first tentative steps were already being taken.

Wing Commander II introduces the possibility of good Kilrathi, thus softening some of the xenophobia of the first game. And yes, it remains completely impossible to take these flying Tony the Tigers seriously.

Most of all, though, Origin poured their energy into the story layer of the game — into all the stuff that happened when you weren’t actually sitting in the cockpit blowing up the evil Kilrathi. Wing Commander II: Vengeance of the Kilrathi took an approach to game design that could best be summed up as “give the people what they want.” With barely six months to bring the project to completion, Origin combed through all of the feedback they had received on the first game, looking to punch up the stuff that people had liked and to minimize or excise entirely the stuff they seemingly didn’t care so much about.

And they found out that what the people had really liked, alongside the spectacular graphics and sound, had been the feeling of playing the starring role in a rollicking science-fiction film. The people liked the interactions in the bar with their fellow pilots, the briefing scenes before each mission, and the debriefs afterward. They liked the characters of their fellow pilots, to whom they claimed an emotional bond that surprised even Chris Roberts. And they liked the idea of all of the missions they flew finding their context within a larger unfolding narrative of interstellar war — even if, taken on its own terms, the story of the first game was so vague as to barely exist at all. Faced with such a sketchy story, alongside a collection of characters that were often little more than ethnic stereotypes, players had happily spun more elaborate fictions in their minds, reading between lines the game’s developers had never drawn in the first place. For instance, some of them were convinced that Angel, the female Belgian pilot, secretly had the hots for the hero, something that came as news to everyone at Origin.

But there were other innovative aspects of the first game which, equally to Origin’s surprise, their customers were less keen on. The most noteworthy of these, and a consistent sore point with Chris Roberts in particular, was the lovingly crafted branching mission tree, in which the player’s success or failure affected the course of the war and thus what later missions she would be assigned. Despite all of Origin’s admonitions to the contrary, overwhelming evidence suggested that the vast majority of players replayed each mission until they’d managed to complete it successfully rather than taking their lumps and moving on. Roberts and his colleagues found this so frustrating not least because they had poured a lot of energy and money into missions which the majority of players were never even seeing. Yes, one might argue that this state of affairs was to a large extent Origin’s own fault, the natural byproduct of a design which assigned harder rather than easier missions as a consequence of failure, thus sending the honest but not terribly proficient player into a downward spiral of ever-increasing futility. Still, rather than remedy that failing Origin chose to prune their mission tree; while limited branching would still be possible, the success and failure paths would be merely slightly modified versions of the same narrative arc, and failing two mission series in a row would abruptly end the game. Origin wanted to tell a real story this time around, and that would be hard enough; they didn’t have time to make a bunch of branching stories.

Given the new emphasis on story, Stephen Beeman was fortunate to have at his disposal Ellen Guon, the very first professional writer ever to be hired by Origin. Guon came to the company from Sierra, where she had polished up the text in remakes of the first King’s Quest game and the educational title Mixed-Up Mother Goose. Before that, she had written for Saturday-morning cartoons, working for a time with Christy Marx, another cartoon veteran who would later wind up at Sierra, on Jem and the Holograms. She’d also seen some of her science-fiction and fantasy stories published in magazines and anthologies, and her first novel, a collaboration with the more established fantasy novelist Mercedes Lackey, was being published just as she was settling in at Origin. Beeman and Guon developed the initial script for Wing Commander II together, learning in the process that they had more in common than game development; Ellen Guon would eventually become Ellen Beeman.

Chris Roberts badly wanted not just a more developed story for the second game but a darker one, an Empire Strikes Back to contrast with the original game’s Star Wars. Beeman and Guon obliged him with a script that sees the Tiger’s Claw, the ship from which the player had flown and fought in the first game, destroyed in the opening moments of the second one by a Kilrathi strike force that, thanks to the secret stealth technology the flying tigers have developed, seems to come out of nowhere. The hero of the original game, who sported whatever name the player chose to give him but was universally known to the developers as “Bluehair” after the tint Origin’s artists gave to his coiffure, is flying a mission when it happens, and through a not-entirely-sensical chain of logic winds up being blamed for the tragedy. But the prosecution fails to prove his negligence or treasonous intent beyond a reasonable doubt at the court martial, and instead of winding up in prison he gets demoted and assigned to fly routine patrols with “Insystem Security” from a station way out in the middle of nowhere. Finally, after years of this boring duty, the Kilrathi unexpectedly come to his quiet little corner of the galaxy, and the “Coward of K’Tithrak Mang” — that being Bluehair — gets his shot at redemption, under circumstances that see him reunited with many of his old comrades-in-arms from Wing Commander I and its mission disks.

The increased emphasis on storytelling — on cinematic storytelling — is all-pervasive. The original game played out in a predictable sequence: conversations in the bar would be followed by a mission briefing, which would be followed by the actual mission, which would be followed by the debrief. Now, the “movie” takes place anywhere and everywhere. In order to inject some cinematic drama into the mission themselves, Origin introduced cut scenes that can play at literally any time as they unfold.

Wing Commander II really is all about the story. It doesn’t want you to spend a lot of time working out how to beat each of the missions; it just wants to keep the plot train chugging down the track. Thus the new adaptive artificial intelligence, which keeps you from ever getting stuck on a mission you just can’t crack. At the same time, however, the selfsame artificial intelligence contrives to make sure that none of your victories are ever routine. “If you meet eight enemies and manage to take out the first seven,” noted Beeman, “the last ship’s intelligence is increased by a few notches. Engaging the last ship results in a really tough dogfight.” Wing Commander II is meant to be a relentless thrill ride like the movies that inspired it, and is always willing to put a thumb on either side of the scale to make sure it meets that ideal.

From a business standpoint — from that of making games that make money — Wing Commander II could serve as something of a role model even today. There was no trace of the indecision, over-ambition, and bets-hedging that so often lead projects astray. Stephen Beeman had a crystal-clear brief, and he achieved his goals with the same degree of clarity, bringing the project in only slightly over time and over budget — not a huge sin, considering that Origin’s original timing and budget had both been wildly overoptimistic. The important thing was that the game was done in plenty of time for Christmas, shipping on August 30, 1991, whereupon Origin was immediately rewarded with smashing reviews. Writing for Computer Gaming World, Alan Emrich optimistically said that the plot had begun “bridging the chasm from ‘genre pulp fiction’ to something that could be more accurately regarded as ‘art.'” Even more importantly, Wing Commander II became another smash hit. It sold its first 100,000 units in the United States in less than two months, and a truly remarkable 500,000 copies worldwide in its first six months.

Yet in my opinion Wing Commander II hasn’t aged nearly as well as its predecessor. Today, the two games stand together as an object lesson in the ever-present conflict between narrative and interactivity. In gaining so much of the former, Wing Commander II loses far too much of the latter. Speaking at the time of the game’s release, Origin’s Warren Spector noted that “we’re still learning how to tell stories on the computer. We’re figuring out where we can be cinematic, and where trying to be cinematic just flat doesn’t work. We’re finding out where you want interaction, and where you want the player to sit back and watch the action.” It’s at these intersections between “being cinematic” and not being cinematic, between interaction and “sitting back and watching the action,” that Wing Commander II kind of falls apart for me.

I’m no fan of bloated, shaggy game designs, and generally think that a keen editor’s eye is one of the best attributes a designer can possess, yet I would hardly describe the original Wing Commander as over-complicated. In the second game, I miss the many things that have been excised as superfluous. I miss the little ersatz arcade game that lets you practice your skills; I miss winning medals and promotions as a result of my performance in the missions; I miss climbing the squadron leader board as I collect more and more kills. In the first game, your wingman could get killed in battle if you didn’t watch out for him properly, resulting in a funeral ceremony, a “KIA” next to his name on the leader board, and your having to fly all by yourself those subsequent missions that should have been earmarked for the two of you. This caused you, for both emotional and practical reasons, to care about the person you were flying with like any good wing leader should. In the second game, however, this too has been carved away. Your wingmen will now always bail out and be rescued if they get too badly shot up. They die only when the railroaded plot demands that they do so, accompanied by a suitably heroic cut scene, and there isn’t a damn thing you can do about it. Wing Commander II thus robs you of any real agency in what is supposed to be your story. Even the idea of a branching narrative, though poorly executed in the first game, could have been done better here instead of being tossed aside as just one more extraneous triviality.

After I published my articles on the first Wing Commander, commenter Jakub Stribrny described his experience with that game:

I decided to do one true honest playthrough. Just one life. If I got shot down, there was no loading the state. I had to start from the very beginning.

And that was when I discovered what the simulator was good for. Since I had only one life I had to make sure I was really prepared before each mission. So I devised a training plan for myself. An hour in the simulator before even attempting the first mission and then two simulator sessions between each subsequent mission. This proved very effective and I was able to clear almost the whole game. In the end I died just a few missions from the end when attempting to attack a group of Jalthi – fighters with extreme firepower – head-on. Stupid.

But I never got so much fun from gaming as when I really had to focus on what’s happening around me, cooperate with my wingman, carefully manage missile use, plan optimal routes between navigation points, and choose whether it’s still safe to ignore the blinking EJECT! light or it’s time to call it a day and survive to fight the battles of tomorrow. Or when I was limping to the home base with both cannons shot up and anxiously awaiting whether the badly damaged and glitching comms system would hold at least long enough for me to ask the carrier for landing clearance. My fighter failed me then and I had to eject in the end, but boy was that an experience.

Wing Commander II obviously pleased many players in its day, but it could never deliver an experience quite like this one. Nor, of course, was it meant to.

In the years that followed Wing Commander II‘s release, a cadre of designers and theorists would unite under the “games are not movies” banner, using this game and its successors as some of their favorite examples of offenders against all that is good and holy in ludology. But we need not become overly strident or pedantic, as so many of them have been prone to do. Rather than continuing to dwell on what was lost, we can try to judge Wing Commander II on its own terms, as the modestly interactive cinematic thrill ride it wants to be. I’m by no means willing to reject the notion that a game can succeed on these terms, provided that the story is indeed catching.

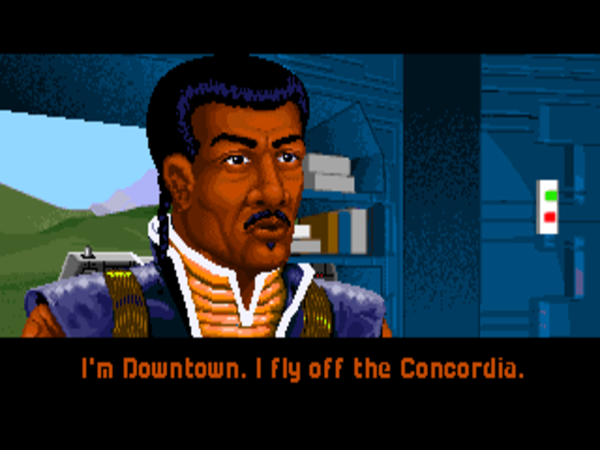

This is hands-down the funniest picture in Wing Commander II, almost as good as the Kilrathi helmets with the ears on top from the first game.

The problem for Wing Commander II from this perspective is that the story winds up being more Plan 9 from Outer Space than The Empire Strikes Back. No one — with, I suppose, the possible exception of Computer Gaming World‘s Mr. Emrich — is looking for deathless cinematic art from a videogame called Wing Commander II. Yet there is a level of craftsmanship that we ought to be able to expect from a game with this one’s stated ambitions, and Wing Commander II fails to clear even that bar.

Put bluntly, the story we get just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. What exactly did Bluehair do to cause the destruction of the Tiger’s Claw, a tragedy for which only he among the carrier’s entire air group was blamed? Why was everyone so quick to believe that a decorated war hero had suddenly switched sides? Why on earth — excuse me, on Terra — would the Terran Confederation reassign someone widely suspected of high treason to even an out-of-the-way posting? And once the game proper gets going, why does Bluehair’s commander persist in believing that he’s a traitor even after he’s saved the life of said commander and everyone aboard his ship half a dozen times? And if the commander does still believe Bluehair is a traitor, why does he keep assigning him to vital missions in between bitching about what a traitor he is and how much it sucks to have him on his ship? Etc., etc.

Now, you could accuse me of over-analyzing the game’s action-movie screenplay, and you’d perhaps have a point. After all, Wing Commander‘s inspiration of Star Wars is hardly the most grounded narrative in the world. What I would also say in response, however, is that there’s a craft — a sleight of hand, if you will — to keeping the reader or viewer from focusing too much on a story’s incongruities. The writer or screenwriter accomplishes this by offering up compelling characters that are easy to root for or against and by keeping the excitement ever on the boil.

And here too Wing Commander II drops the ball. At the center of the action is the charisma vacuum that is Bluehair. The first game held back on characterizing him, letting the player imagine him to be the person she wished him to be. That can no longer work in the more developed narrative of the second game, but Origin still seems reluctant to fill in the lines of his character, with the result that he falls smack into an uncanny valley between the two classic models of the adventure-game protagonist: the fully fleshed-out individual whose personality the player is expected to assume, and the proverbial “nameless, faceless adventurer” that she can imagine to be herself. Bluehair becomes what my dear old dad would call a “lunk,” a monosyllabic non-presence who rarely has much to say beyond “Yes, Sir,” and “No, Sir.” It feels like a veritable soliloquy when he can manage to muster up an “I’m not guilty, sir. I won’t sign it!” or a “Go to hell, Jazz!” And when the romance subplot kicks in — duly following the stated desires of their players in this as in all things, Origin made Angel the love interest — it starts to get really painful. One does have to wonder why everyone is getting so hot and bothered over this guy of all people. Luke Skywalker — much less Han Solo — he definitely ain’t.

So, we might ask, how did we wind up here? How did one of the first Origin games to take advantage of real, professional writers not turn out at least a little bit better? A strong clue lives in a document that’s been made public by the website Wing Commander Combat Information Center. It’s the initial script for the game, as prepared by Ellen Guon and Stephen Beeman and completed on November 29, 1990, before production got underway in earnest. The version of the story found herein differs considerably from that found in the completed game. The story is more detailed, better explained, and richer all the way around, including a much more dynamic and assertive Bluehair. It might be instructive to compare the opening of the story as it was originally conceived with that of the finished game. Here’s how things started back in November of 1990:

Establishing shot — Tiger’s Claw floating in space.

Narration: CSS Tiger’s Claw, six months after the Vega Sector Campaign…

Establishing shot — Tiger’s Claw briefing room. We can’t tell yet who the commander is.

Bluehair: Okay, everyone, settle down…

Cut to Bluehair. Now we see that Bluehair is in Colonel Halcyon’s familiar position.

Bluehair: Pilots, I’d like to welcome you to the Tiger’s Claw. I’m Lieutenant Colonel Bluehair Ourhero, your new commanding officer. I hope everyone’s recovered from the farewell party for Paladin, Angel, Spirit, Iceman, and General Halcyon.

Hunter: An’ don’t forget that bloody lunatic, Maniac! They finally transferred ‘im to the psych ‘ospital.

Bluehair: Sad but true, Hunter. Now, pay close attention, pilots. We’ve just been assigned a top-priority mission, to spearhead a major raid deep into Kilrathi space to their sector command post in the K’Tithrak Mang system. The plan is to jump in with a few carriers and Marine transports, hit the starbase hard, then jump out.

Hunter: ‘nother bleedin’ starbase, eh?

Bluehair: (smiles) You got it, mate. Let’s just hope it’s as easy as the last one. Now, listen close, everyone. Knight and Bossman are Alpha Wing — check for enemy fighters at Nav 2 and 3. Kilroy and Sabra are Beta Wing…

Narration: You assign all the wings. All but one.

Bluehair: I saved the most important wing for last. Computer, display Kappa. On our way to the starbase, the Claw will pass close to the asteroid field at Nav 1. We don’t know what’s out there, so Hunter and I are going to sweep the rocks as the Claw begins its approach. We’ll either take out whatever we find or hightail it back here to warn the Claw. Any questions, pilots? Good. The Claw will complete her last jump in approximately seven minutes. Get ready for immediate launch. Dismissed.

Animation of crowd rising — different backs! Animation of Tiger’s Claw jumping.

Narration: K’Tithrak Mang system, deep within Kilrathi space.

Animation of launch-tube sequence.

Mission 0. This really should be a basically easy mission. However, just as Bluehair is returning to the action sphere that contains the Claw, we cut to a canned scene.

Bluehair: No!

The Tiger’s Claw floats in the medium distance. Close to us, three Kilrathi stealth fighters in a chevron uncloak, launch missiles, then peel off in different directions. The missiles impact the Claw and blow it to kingdom come.

Dust motes are zooming past us, as if we were headed into the starfield. Now a space station appears in the far distance, rapidly getting closer. We zoom in on this until we start moving around the station. As we do so, the planet Earth comes into view on one edge of the screen. The station itself remains center frame.

Narration: Confederation High Command, Terra system, six months after the destruction of the Tiger’s Claw.

Admiral Tolwyn presides over Bluehair’s court martial. A very formal-looking bench with seven dress-uniformed figures, Tolwyn in the middle, is in the back pane. Bluehair and his counsel are sitting at a table. Spot animations of camera drones with Klieg lights will help convey the information that this trial is based more on media image than justice.

Tolwyn: Lieutenant Colonel Ourhero, stand at attention. Lieutenant Colonel Ourhero, you stand accused of negligence, incompetence, and cowardice under fire. Your actions resulted in the death of 61,000 Confederation defenders. Despite your plea of not guilty and your ridiculous claim that the Kilrathi used some non-existent stealth technology, flying invisible ships past your position…

Bluehair: It’s true, sir.

Tolwyn: …you are obviously guilty of these crimes against the Confederation. But, fortunately for you, this court cannot prove your guilt. Our primary evidence, your black-box flight recorder, is missing from the Confed Security offices. Because of the lack of physical evidence, this court is required by law to dismiss your case. We find you not guilty of crimes against the Confederation. This court is adjourned. Lieutenant Colonel Ourhero, report to my office at once.

Establishing shot — Tolwyn’s office

Tolwyn: I wanted to talk to you in private, Bluehair. The court couldn’t convict you because of a technicality, but we all know the truth, Ourhero. You’re a coward and a traitor, and I’ll personally guarantee that you’ll never fly again. Your career with the Navy is over. As I assumed that you have some small amount of honor left, my secretary has drawn up your resignation papers…

Bluehair: I won’t resign, Admiral.

Tolwyn: What??

Bluehair: I’m not guilty, sir. I refuse to resign.

Tolwyn: Then I’ll offer you one more option, just because I never want to see your face again. I have a request from Insystem Security for a mid-ranked pilot. If you’ll accept a demotion to captain, it’s yours. Otherwise, pilot, you’re grounded for life.

Bluehair: I’ll accept the demotion, sir.

Tolwyn: Very well. Get out of here… and you’d better hope we never meet again, traitor.

Below you can see the finished game’s interpretation of the story’s opening beats.

Some of the choices made by the finished game, such as the decision to introduce the villain of the piece from the beginning rather than wait until some eight missions in, are valid enough in the name of punching up the anticipation and excitement. (One could, of course, still wish that said introduction had been written a bit better: “Speak of your plans, not of your toys.” What does that even mean?) In other places, however, the cuts made to the story have, even during this opening sequence, already gone deeper than trimming fat. Note, for instance, how the off-hand epithet of “traitor” which Admiral Tolwyn hurls at Bluehair in the initial script is taken to mean literal treason by the final game. And note how the shot showing the court martial to be a media circus, thus providing the beginning of an explanation as to why the powers that be have chosen to scapegoat one decorated pilot for a disastrous failure of a military operation, gets excised. Much more of that sort of subtlety — the sort of subtlety that makes the story told by the first draft a credible yarn within its action-movie template — will continue to be lost as the game progresses.

There’s no single villain we can point to who decided that Wing Commander II should be gutted, much less a smoking gun we can identify in the form of a single decision that made all the difference. The closest we can come to a money quote is this one from Chris Roberts, made just after the game’s release: “We learned some lessons. We tried to do too much in too little time. None of us had any idea that the game had grown so large.” Like politics, commercial game development has always been the art of the possible. Origin did the best they could with the time and money they had, and if what they came up with wasn’t quite the second coming of The Empire Strikes Back which Roberts had so wished for, it served its purpose well enough from a business perspective, giving gamers a much more concentrated dose of what they had found so entrancing in the first game and giving Origin the big hit which they needed in order to stay solvent.

Origin, you see, had a lot going on while Wing Commander II was in production, and this provides an explanation for the pressure to get it out so quickly. Much of the money the series generated was being poured into Ultima VII, a CRPG of a scale and scope the likes of which had never been attempted before, a project which became the first game at Origin — and possibly the first computer game ever — with a development budget that hit $1 million. Origin’s two series made for a telling study in contrasts. While Wing Commander II saw its scope of interactivity pared back dramatically from that of its predecessor, Ultima VII remained as formally as it was audiovisually ambitious. Wing Commander had become the cash cow, but it seemed that, for some at Origin anyway, the heart and soul of the company was still Ultima.

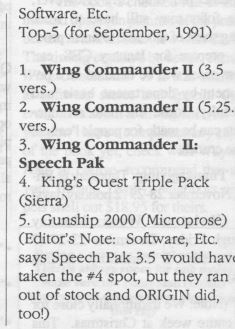

Origin thus continued to monetize Wing Commander like crazy to pay for their latest Ultima. In a cash grab that feels almost unbelievably blatant today, they shipped a separate “Speech Accessory Pack” simultaneously with the core game. It added digitized voices to a few cut scenes, such as the opening movie above, and let your wingmen and your Kilrathi enemies shout occasional canned phrases during missions. “You want to buy our new game?” said Origin. “Okay, that will be $50. Oh… you want to play the game with all of the sound? Well, that will cost you another $25.” Like so much else about Wing Commander II, the speech, voiced by members of the development team, is terminally cheesy today, but in its day the Speech Pack drove the purchase of the latest Sound Blaster cards, which were adept at handling such samples, just as the core game drove the purchase of the hottest new 80386-based computers. And then two more add-on mission disks, known this time as Special Operations 1 and 2, joined the core Wing Commander II and the Speech Pack on store shelves. Well before the second anniversary of the first game’s release, Origin had no fewer than seven boxes sporting the Wing Commander logo on said shelves: the two core games, the four add-on mission packs, and the Speech Pack. Few new gaming franchises have ever generated quite so much product quite so quickly.

Of course, all this product was being generated for one reason only: because it sold. In 1991, with no new mainline Ultima game appearing and with the Worlds of Ultima spin-offs having flopped, the Wing Commander product line alone accounted for an astonishing 90 percent of Origin’s total revenue. Through that year and the one that followed, it remained undisputed as the biggest franchise in computer gaming, still the only games out there scratching an itch most publishers had never even realized that their customers had. The lessons Origin’s rivals would draw from all this success wouldn’t always be the best ones from the standpoint of games as a form of creative expression, but the first Wing Commander had, for better or for worse, changed the conversation around games forever. Now, Wing Commander II was piling on still more proof for the thesis that a sizable percentage of gamers really, really loved a story to provide context for game play — even if it was a really, really bad story. After plenty of false starts, the marriage of games and movies was now well and truly underway, and a divorce didn’t look likely anytime soon.

(Sources: the book Wing Commander I & II: The Ultimate Strategy Guide by Mike Harrison; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin from June 21 1991, August 7 1991, October 11 1991, October 25 1991, November 8 1991, January 17 1992, March 13 1992, and May 22 1992; Retro Gamer 59; Computer Gaming World of November 1991. Online sources include documents hosted at the Wing Commander Combat Information Center, US Gamer‘s profile of Chris Roberts, The Escapist‘s history of Wing Commander, Paul Dean’s interview with Chris Roberts, and an interview with Richard Garriott that was posted to Usenet in 1992.

Wing Commander I and II can be purchased in a package together with all of their expansion packs from GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Stephen Beeman now lives as the woman Siobhan Beeman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|