Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls, Legend Entertainment’s debut title, had striven to tick every box a parser-driven game possibly could to ensure commercial success in the games market of the early 1990s. It was a fantasy game, traditionally adventurers’ favorite fictional genre; it was written by Steve Meretzky, the lost and lamented Infocom’s most famous author; it had a strong, fairly linear plot line to keep the action moving and keep the player on track; and of course it topped off everything else with the added attraction of sex.

Timequest, Legend’s second game, had none of this going for it. As a time-travel story, it was ostensibly science fiction, but was far more interested in real-world history; it was written by Bob Bates, another former Infocom author but one whose name and games only the most devoted of the old fans recognized; it had little plot to speak of beyond the beginning and the endgame, with a huge middle that was almost aggressively non-linear; and it was usually fairly sober where Spellcasting 101 was silly and titillating. For all these reasons, Timequest was considered by even its author to be an “experiment.”

Its experimental nature wasn’t down to any radical design innovations. On the contrary: if anything its approach was more typical of text adventures past than that of Spellcasting 101. Timequest was rather a commercial experiment, which sought to answer the question of whether gamers in 1991 would still buy a game like this one — buy a game that was complicated, nonlinear, and somewhat difficult. As such, it hearkened back to a theme which had been a hidden undercurrent of Bob Bates’s career in games to date. Raised in a family where really hard puzzles had been a hobby of many, he had originally taken the name of Challenge — the first text-adventure developer he founded, half a decade before he founded Legend — quite literally. Infocom, as he judged it, was going soft by the mid-1980s, focusing too much on easier, more accessible games. Challenge would make hard games for the hardcore puzzlers Infocom was now disappointing.

As things transpired, however, that vision of Challenge never came to fruition. Bates wound up writing games for Infocom instead of in competition with them, and wound up hewing to the directives coming down from them to continue down the road of accessibility. But he never forgot what he had originally intended Challenge to be, and, after co-founding Legend, he jumped at the chance to finally make a game cast in that mold.

Indeed, the game most obviously similar to the one he was now embarking upon has a well-earned reputation as one of the most difficult adventure games ever made. Sierra’s 1982 text adventure Time Zone is, like Timequest, a merry nonlinear romp through history, allowing its player to visit seven continents in eight time periods, ranging from 400 million BC to 4082 AD, with no guidance whatsoever beyond “go forth to explore and solve puzzles.” Even the people who made Time Zone were shocked when someone — likely with a lot of crowd-sourced help from the early online community The Source — managed to solve it in mere weeks rather than months or years.

But the reality of the finished Timequest is actually less intimidating than either that specific point of comparison — a game which Bob had never played or even heard of at the time he began his own time-travel epic — or the general buildup I’ve been giving it might imply. Whatever his stated aspirations for creating a challenging adventure, Bob Bates, throughout his career one of the great advocates for fairness and sanity in adventure design, seems almost congenitally incapable of treating his players too badly. The difficulty of Timequest doesn’t really live in the individual puzzles, about which I’ve actually heard some players complain that they’re too straightforward. No, the difficulty, to whatever extent it exists, is rather bound up in the sheer size of the thing. It’s almost as vast in area as Time Zone and much, much vaster in its historical detail, with a field of play sprawling over six locations in nine time periods, ranging from 1361 BC to 1940 AD. Sherlock: Riddle of the Crown Jewels and Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur had already demonstrated — the former in somewhat more compelling fashion than the latter — Bob’s love for history. Timequest, then, was his chance to let that love run wild on a stage that was almost as large as human history itself.

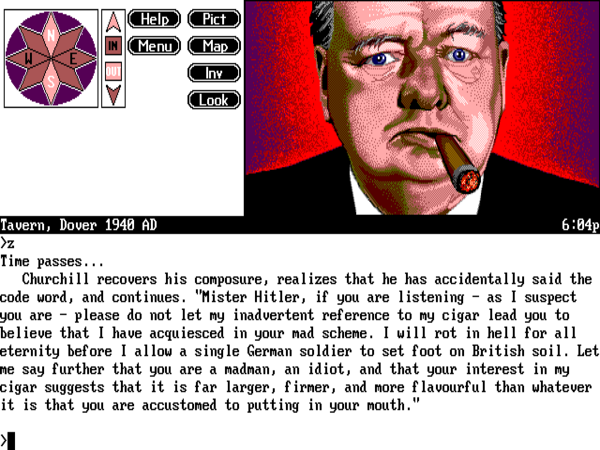

The framing story behind this grand journey through time and space makes only as much sense as it needs to in order to set the adventure in motion, and winds up making even less sense once all is said and done and the inevitable final time-travel twist has been piled on top. It seems — at the beginning, anyway, which is as far as I’ll go here — that a rogue agent of the Temporal Corps of 2090 AD has set off to deliberately wreck the time stream and thus remake all of human history. To do so, he’s visited ten examples of what we might refer to as historical choke points — pivotal, transformational moments — ranging from the brief-lived Roman dictatorship of Julius Caesar in 44 BC to Britain’s refusal to surrender to Nazi Germany in 1940 AD. Although re-doing these events which the rogue agent has undone will be the goal of your quest, you’ll have to visit many more than just these places and times in your “interkron” in order to accomplish that goal, collecting vital objects and information from each possible place and time. Meticulous note-taking — a keeping track of everywhere you’ve been and what you’ve done and found there — is a must. One or two tricky puzzles aside, it’s this combinatorial explosion that’s the real source of Timequest‘s difficulty.

In other ways, though, Timequest rather belies its conception as an experimental throwback to the adventures of yore, as it does its status as a point of comparison with the infamously unfair Time Zone. In what can only be regarded as a remarkable design feat in its own right, Timequest implements all its sprawl while making it very nearly impossible to lock yourself out of victory. (Bob and I have found two exceptions to that rule, one involving a rock you find on the street outside the residence of a certain famous French emperor and the other a lighter used by a certain famous British prime minister, but both are the results of oversights rather than intentional design decisions.)

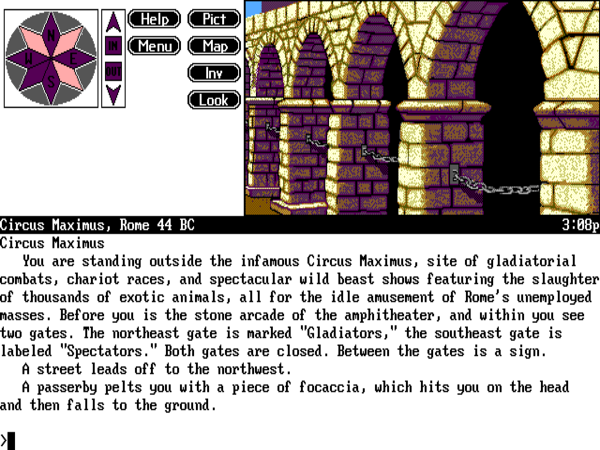

Sometimes the lengths Timequest goes to to save you from yourself can be almost comical. If, for instance, you fail to visit the stands in the Colosseum of Rome in 44 BC and buy some focaccia from a vendor before the chariot races end and the place is locked down, never fear, Bob Bates has got your back — or your head, as the case may be.

I should love Timequest, given the love for history and the love for challenging-but-fair adventure games which I happen to share with its designer. Yet I have to say that I’m slightly less excited by some of the details of its execution than I am by the core idea. By far the biggest adventure game Legend would ever make in terms of breadth, it’s also, unfortunately but perhaps inevitably, the shallowest in terms of implementation depth. Much that ought to work, but that isn’t required to solve the puzzles, simply fails to work for no good reason. These flaws can feel particularly jarring to the modern player, what with the accepted sweet spot in interactive fiction having long since moved from sparsely implemented epics like this one to smaller but deeper, more richly implemented games.

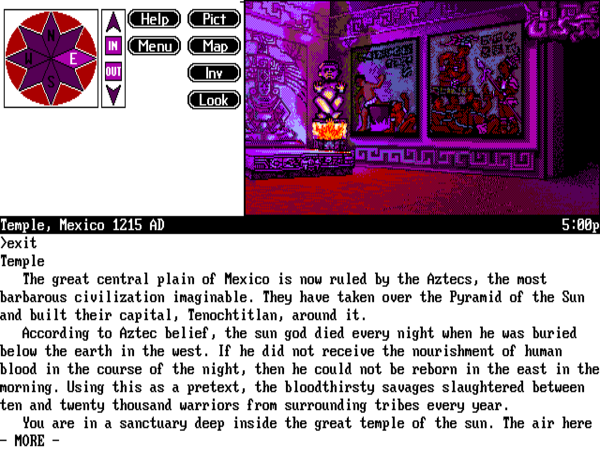

There’s just not that much to do or even to look at in many of the time/location combinations you visit in Timequest — only as much as is absolutely required by the game’s puzzles and plot. That said, it should also be said that the sparsity isn’t uniform; the various locations fare quite differently by this standard. Dover, England, is reasonably well-done, while Rome feels like the most lovingly fleshed-out of all of the places, with lots of new details to observe when you visit it in a new time and a real sense of a passage of time that reveals both continuities and changes. Predictably enough given the game’s point of origin, the non-European locales — Peking, Mexico, Baghdad, and Cairo — fare much less well, often remaining in a sort of under-implemented stasis for spans of hundreds or thousands of years. Even the historical choke points that claim to deal with these cultures wind up referring back to their influence on Western history: you must prevent the Arab world in 800 AD from extending its dominion into Europe; similarly, you must make sure that Genghis Khan conquers Peking in 1215 AD only to make sure he doesn’t get frustrated and lash out at Europe instead; you must make sure Hernando Cortez of Spain succeeds in conquering the Aztecs in 1519 AD. Freely acknowledged by Bob as a byproduct of his own American upbringing, the Euro-centric tunnel vision makes this game that claims to be about the entirety of human history rather more provincial than that claim would imply.

Timequest waxes a bit judgmental on the subject of Aztec civilization. But then, if you can’t get judgmental about a civilization with a penchant for human sacrifice on a massive scale, what can you get judgmental about? (Bob’s take on the subject does stand in marked contrast to Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer,” one of rock music’s many great songs with painfully stupid lyrics.)

But I don’t want to criticize Bob too heavily for this failing; steeped in Western history as I am as well, I’m sure I’d have a hard time doing much better. A fairer point of criticism is a more generalized sense of sketchiness, not only in the implementation but also in the writing. Simply put, Bob’s words here don’t often read as hugely considered — or even as read by anyone much at all prior to the game’s release. In a game that’s intended to evoke history, that’s intended to show changing cultures across huge swathes of time, the fact that the writing often doesn’t even try to evoke any sense of atmosphere is, to say the least, unhelpful. Absolutely everyone you meet speaks in the diction of a late-twentieth-century American — except for those you meet in Dover, who spend their time sitting around in the pub speaking Cockney, whether it’s 1361 BC or 1940 AD. (I’ve heard of the timelessness of English pub life, but this is ridiculous.) Combined with the sparse implementation, the dashed-off writing rather smacks of a game released before its time, finished in a last-minute frenzy and pushed out the door. When I asked Bob about this, he didn’t recall feeling like the game had been released too soon; nevertheless, the impression remains, and that’s damning enough in itself.

My final point of contention with Timequest applies to a couple of the puzzles. I won’t spoil either of them here — you’ll have to wait for the conversation with Bob that follows this review for that — but I will say that each hovers right on the borderline of what I consider fair, and each could have been improved greatly in my opinion by either one more little nudge or one less level of complexity. Had Timequest been produced at Infocom when the latter’s storied adventure-making machine was running at its peak mid-1980s efficiency, these are the sorts of puzzles which probably wouldn’t have made it unchanged into the finished product. For that matter, Jon Palace, Infocom’s unsung hero in matters of quality control and so much else, would probably have demanded that the writing be punched up a bit as well. With all its strengths in terms of scope and vision, Timequest also serves to demonstrate that Legend, despite the best of intentions and an understandable eagerness to claim the mantle of heir to Infocom, didn’t quite have the institutional resources at their disposal — at least not yet — to entirely live up to that heritage.

For me, then, Timequest is a mixed bag, a game I certainly don’t hate but one I wish I could love a little more than I do. Of course, it’s possible that my love for the idea of a globe- and century-trotting time-travel game perversely makes me judge the execution of same more harshly than I otherwise might. I can only say that Timequest, while a huge improvement on the likes of Time Zone, still isn’t the time-travel adventure of my dreams.

For Legend as well, Timequest wound up falling into an unsatisfying middle ground, proving neither a dismal flop nor a rousing commercial success. Despite garnering a coveted Computer Gaming World cover feature upon its release in May of 1991, it failed to sell as well as had Spellcasting 101 — nor even as well as would Spellcasting 201, which would be released a few months later in 1991. Legend was thus forced to judge their commercial experiment to have been a qualified failure. Future Legend adventure games, including those from Bob Bates himself, would hew to the Spellcasting rather than the Timequest model in terms of design. It’s hard to lament this turn of events too terribly, given that that approach would yield some very strong work, including some games that are in my opinion considerably stronger than Timequest. But for players who loved big, traditional, wide-open, non-linear text adventures, Timequest was indeed the end of the line in terms of boxed commercial games. Thankfully, an amateur interactive-fiction community — or, perhaps better said, communities — were picking up steam, ready to take up the slack.

Bob Bates on Timequest (or, Hoisting Bob Bates with His Own Petard)

When I first started talking to Bob Bates about Legend’s early history some time ago, we agreed that it would make an interesting exercise for him to revisit Timequest, his largest and most challenging adventure game ever, and see what he himself thought of it now, more than a quarter of a century since he last played it. He’s since taken time out of his busy schedule to do just that. I talked to Bob twice over the course of an endeavor that wound up taking much longer than he had anticipated: we talked once when he was midway through the game, then again just after he finished it. What follows are some of the highlights of those two conversations, at least as they pertain to Timequest. (Bob and I do have a bad tendency to wander off-topic.) For anyone who’s ever wished there was a way to put the designer of the game you’re playing through the same pain you’re going through, this dose of schadenfreude is for you.

In the text that follows, my comments and questions are in boldface and Bob’s responses are in normal print. We do spoil parts of the game, obsessing in particular over two questionable puzzles involving a sultan’s harem and the entrance to the endgame, so you may wish to postpone reading our conversation for the time being if you haven’t yet played the game and would like to tackle it completely unspoiled. And naturally, those of you who have played the game and know the puzzles of which we speak will find what follows most enlightening of all — although I did sneak in some footnotes to explain some of the finer points to the uninitiated.

Part 1: Our intrepid author feels a bit lost within his own game…

So, how goes it with Timequest?

Well… I’m not done. As I play, I’m sitting here going, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe I did that!” The number of restore puzzles that are in there… the overall level of difficulty is so much greater than anything I would make today.

Ha!

But before we get into your recent experiences in the game, maybe we could talk just a little about this idea of Timequest as an experiment to see if there was still a market for a very complicated, very taxing adventure game. That’s a theme that goes back even further in your career. You’ve mentioned before that you took the name of your first company, Challenge, quite literally. You had thought that Infocom was losing their edge, becoming too accessible. You wanted to create more difficult games, harking back to the early Infocom games. Of course, that vision changed once you started actually working for Infocom.

Maybe you could talk about this desire to do a really difficult adventure game, and to what extent Timequest in fact met that standard. It’s a very difficult game in that it demands a lot of note-keeping and planning from the player, but I think that most of the actual puzzles — with maybe one or two exceptions, which we can talk about later — are fairly straightforward. It’s more the combinatorial-explosion factor that makes it more difficult.

I come from a family of puzzle-doers — doers of hard puzzles. During the four years I spent living in England, I was exposed to the English style of crossword puzzle. Are you familiar with English as opposed to American crossword puzzles?

Are you referring to acrostics, or…

No. English crossword puzzles are regular crossword puzzles, but they’re an order of magnitude more difficult. In an American crossword, a clue might be “a kind of boat,” and the answer might be “yacht” or “raft” — very straightforward. English crosswords rely on really obscure puns and references and clues hidden within the clues themselves. A clue might be “united undone.” And the answer is “untied.” In other words, if you “undo” the word “united” by scrambling the letters, you come up with “untied.” That would be considered a no-brainer clue. Take that and make it much harder, where the answer involves a Medieval English word for “plow” or something. They have dictionaries dedicated to these really obscure words. These are the kinds of puzzles my family did; my dad was a cryptographer for the NSA. That’s the level of mental challenge I was used to.

I therefore thought everybody was the same. As you grow up, you think your family is normal and does the things all families do. So, when I’d play an Infocom game, I’d say, “Yeah, okay, it’s hard. But it’s not really hard. Isn’t there a market for really hard?” And that of course was the mistake of Challenge: no, there wasn’t a sufficiently large market for really hard.

So, Infocom comes along and I do games for them. The push there was to make the games easier. Then Infocom went away, and the point-and-click adventure games that were left out there weren’t hard at all. It’s not so much that I wanted to make a really, really hard game with Timequest. I just wanted to make one that was as hard as a Standard-difficulty Infocom game. I wanted to find out if the Infocom market was still there, but hidden within this larger market of point-and-click players. Is there still a market for a reasonably difficult game, or do we have to make all of our games easier?

I have to assume, based on the games Legend went on to release after Timequest, that the answer to that question was yes — that you did have to make all of your games easier. I like the Gateway games and Eric the Unready a lot, but they’re different from Timequest in that they’re much more narrative-driven games — there’s a constantly unfolding plot pushing you through, so that you always have a pretty good idea of what you should be doing. But in Timequest you’re just thrown into this huge labyrinth of time periods and locations, and the game just kind of says, “Okay, figure it out.”

Yeah… I had started out to make a Standard-difficulty Infocom game, but it turns out I made a game that was harder than that. I didn’t understand why people found it more difficult than I had intended. I’m speaking with two minds here because as I play the game now, I’m saying, “What was I thinking?” Now I’m playing like a player instead of like the designer, having not looked at it for a quarter of a century. I’ve forgotten most things in the game, so I’m approaching it fresh.

I remember being bewildered that people were finding the game so hard to approach. I’d put in these mission papers with the critical events. Obviously what you needed to do was to go to the time periods and locations that were called out and look at what clues and puzzles were there, then fan out from there. But I remember the testers saying they didn’t know where to start. So I said, “Okay, I’ll make it even easier.” When you first get into the time machine — the interkron — it will be preset to Rome in 44 BC — a clear indication of where you should go. That’s a self-contained little puzzle environment. When you finish with that, Cleopatra tells you to come see her. So, obviously the next thing to do is to go to Cairo in that same year. And then you can continue to go to the places in the briefing papers. That was my thinking at the time.

Fast-forward to two weeks ago. I picked up the game and started to play, and realized I had no idea where to go or what to do. So, I started in the oldest time slot on the left-hand side of the map — Mexico, 1361 BC — and worked my way across the map. Then I went to the next one, 44 BC, and did the same, and so on and so on. I’ve been doing that for the last ten hours or so, and just before this call I got up to Dover in 1215 AD and the King John puzzle.

My notes are pretty funny. “I did this, then I died. So I restored. I tried this and I died. So I restored. Then I learned this — but I died.” Here I am, priding myself on being a designer who doesn’t make restore puzzles… and, my God, they’re all over the place!

When I played the game, I did exactly as you are. I started in 1361 BC and visited each location, then continued chronologically forward. After visiting a location, I would mark in my notes whether I thought I had done everything there — usually you have a pretty good idea — or whether there were obviously still things to be done, which probably meant I was missing an item from another location. So I lawn-mowered through all of the locations and time periods once. Then I had a big collection of stuff, and I could start through all of the locations that were not yet solved again. I did that two or three times, and I was ready for the endgame. There were only one or two puzzles that really gave me a hard time. Otherwise, I think it was the need for note-keeping and just the logistics of the whole thing that might be a challenge for some players. The puzzles themselves, taken in isolation, are usually quite straightforward.

That’s exactly how it seems to me. I look at some of these puzzles and say, “Well, that’s obvious.” And I do have some memories of some of the puzzles. So, when I came across the Aztec who is looking for the Feathered Serpent… my notes really are kind of funny: “I guess I have to find something that makes me look like that.” And I remember that when I get to the Spanish Armada I find a helmet that plays into the Mexican puzzle line. I’m thinking maybe that helmet has a feather plume or something on it.

Then when the Aztec temple has been built, there’s a maze — I can’t believe I did a maze puzzle, but there it is — and I found a costume there. So obviously I’ve got to go back wearing the costume. But I still haven’t fully solved that. I went back and the guy killed me anyway. Yeah… there’s a guy who throws a spear at me, and I haven’t figured out how to deal with him.

Yeah, you have about two turns before he kills you…

Yeah. How’s that for a restore puzzle?

So, my impressions are the same as yours. I found some chalk in Dover, then I got to Cairo and there’s a deaf beggar standing there with a slate. Okay, “give chalk to beggar.” That’s not brain surgery.

Although I haven’t figured out what these messages are that Vettenmyer is leaving. [1]Zeke Vettenmyer is the guy we’re chasing, the one who’s mucked up the time stream. The showdown with him will come in the endgame.

Really, you don’t remember that?

No!

It becomes very important…

The weird thing is that you get a point for each one. I know myself, and I know that it’s really unlikely that I would allow the player to end the game without getting all the points. Maybe I would have done that back in the day, but it doesn’t seem like a part of my personality. I remember having a conversation with Steve Meretzky at one point about the difficulty of ensuring that the points come out right. I said, “Boy, this is really hard!” And he said, “No, it’s not hard at all.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “When you get to the end, for the last puzzle, you just take the total number of points there are supposed to be in the game and give the player the number of points still needed to get to that.” And I thought, Wow! There’s one thing in the world that I’m more particular about than Meretzky.

I think you could finish Timequest without all the points if you didn’t collect all the messages, but you would almost have to be relying on outside knowledge — a walkthrough or hint book, or you would have to have played before and just not have bothered to collect the messages this time through. They’re telling you something which you need to know.

Yeah, that sounds like me. I’m thinking maybe I can arrange them in some order so the first letters or the last letters spell something out. Or maybe take the first word of the first message, second word of the second message, etc. So, I’m just writing them down. At some point I figure I’ll need them. [2]Bob has hit upon the solution already. Each of the 19 messages has a number embedded within it in some fashion, from “Zeke is number one!” to “This is the last message I will leave you in the nineteen-hundreds.” First, you have to arrange the messages in numerical order; then, you have to read down the first letter of each message to learn the password to the endgame area. Bob and I will discuss this puzzle at more length — including why I don’t like it all that much — in our second chat.

Good strategy!

And again, knowing myself, I’d bet that one of the reasons they’re scattered about like this is that I had a lot of locations with nothing to do. Even now as I play the game I’m annoyed when I get to a location where I can’t do anything. I probably used the messages to make at least some of those places not completely worthless. It would surprise me if I left any location completely barren. I’m a designer who wants to reward the player for what he does. If someone does the equivalent of a pixel hunt by, as you put it, “lawn-mowering” through all these locations, he should be rewarded for that. I hope every location does turn out to have something worthwhile.

Timequest has a lot of restore puzzles, but there aren’t any places where you can do something wrong and lock yourself out of victory without realizing it, except perhaps for one or two situations that I believe were the result of oversights rather than deliberate design decisions.

Yeah. When that happens, your wristlet vibrates to tell you you’ve screwed up. That’s a mechanic that was put in in order to avoid the “dead man walking” syndrome. That’s something I work hard to avoid.

So, even though you saw Timequest as a kind of throwback to a more classic form of adventure game, that aspect of it is really quite modern, quite forward-looking. Sierra at this time, for instance, was still littering their games with dead ends. And that is of course the thing most players hate worst of all. If a game kills you… okay, you died — restore, life goes on. But to get to the end of the game and realize you needed to have done something 1000 turns ago, that’s just the worst.

Yes, I was certainly aware of that, and would have figured it into my design: to be able to quickly know when you’re in trouble or you’ve done something wrong, and to know that the designer isn’t going to screw you over.

There’s a lot, including that, that I like a lot about Timequest, but there are also some things that don’t thrill me so much. And of course it’s often more educational to talk about where a game falls down a bit than what it does well. So, I thought I would tell you a couple of ways in which I thought Timequest was a little bit lacking.

That would be fine as long as they aren’t things I haven’t encountered yet.

Okay. One is very general, so let me start there.

I couldn’t help but notice that there’s more detail in some places than others, so much so that I wonder if the game was a bit rushed. For instance, the Rome setting is done very well. It feels very fleshed-out; as you visit Rome in different time periods you get a real sense of how the city is changing. But for Mexico, there are several time periods where it just seems like the same place. I’m curious if you noticed that yourself while playing the game now, and if you recall what might have led to that disparity on the design side.

It wasn’t time pressure. It’s more what I knew, what I could bring to the party. I know a lot about English and European history. I don’t know much at all about other regions’ history. And of course the written record for other regions isn’t always there.

I wanted to spread the game out across the world and spread it across cultures that had existed for a very long time. For that reason, Dover, Rome, and Cairo were obvious. Then I looked at a map thinking, okay, what can I do in the Americas? I couldn’t do in anything in North America; we just don’t know enough about those Native American cultures. But there was this rich culture in Central America. But what fits my model there? Well, we’ve got this really unusual occurrence where this guy — Cortez — shows up and conquers the Aztecs. How could that have happened? So, I went with this myth about the Feathered Serpent, which has some basis in history.

So the whole Mexico scenario is built around this one almost unchanging temple complex for two reasons. One of the cool things about a time-travel game is that you can do things in the past that affect the future. By the time this game was being made, mazes were already a subject of much consternation and controversy among players. But I’d done a maze in Arthur where instead of dropping items you have to make marks on the wall. So I did a maze which really wouldn’t be a maze at all if you saw it when it was being built. You had to follow these footprints and write down the directions because in a later time period it would all be dark.

When I first got to the maze, while it was being constructed, I started trying to write on the walls like in Arthur. But now that I’ve solved it I remember my thinking clearly.

The other reasons is that I really don’t know much about Mexican history. I have no idea what the game will do when I get to 1940 AD Mexico because the Mexico puzzle sequence kind of stops before that. [3]The game just tells you that you can’t go there.

I think you’ll be surprised and possibly a little disappointed…

There’s probably just another message from Vettenmyer or something.

And the same applies to China. I’d never been to China; I’d never been to Mexico either.

Yes, Peking as well feels very static. It feels like pretty much the same place over a span of thousands of years. Rome and Dover have a much greater sense of changing times.

Yes. You can read about the history when you first enter a time period, but it’s not really important in Peking or Mexico. Whereas in the European locations it is more important.

And often the non-European scenarios end up being important for the effect they could have on European history. So, in one choke point Genghis Khan is trying to invade Peking; if he doesn’t succeed, he’ll turn on Europe instead. And at another point you have to prevent the Muslim lands in the Middle East from taking over Europe. So you’re looking at the histories of these cultures through the lens of their possible effect on European history.

Yeah, that’s just because of me; who I am and what I know.

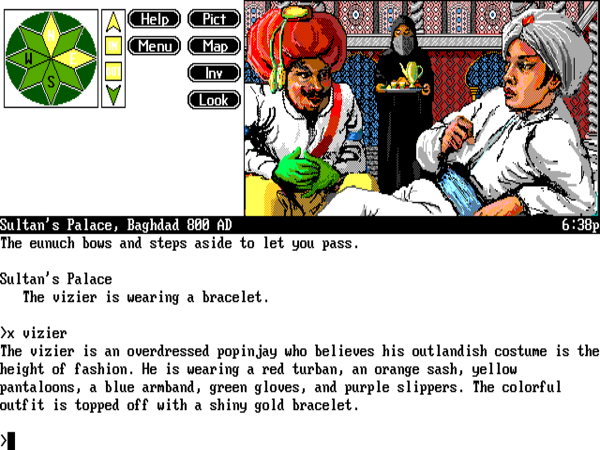

So, have you gotten to the puzzle sequence that takes place in Baghdad in 800 AD, where you have a sultan and a vizier who’s having an affair with a woman in the sultan’s harem?

Yeah, I’ve solved that one.

Okay. I thought that puzzle had one layer too many.

Yeah, I still don’t understand it.

Yeah. When you can solve a puzzle without understanding it, that’s a problem. Back in Zork II there was this puzzle about the Bank of Zork that everybody hates. Most players would just randomly stumble on the solution and continue, but that’s not satisfying at all.

I’ll tell you exactly where I am with the harem puzzle right now. I’m looking at the vizier, who’s really dressed strangely, wondering if there’s some sort of ROYGBIV puzzle going on. But I think he’s wearing one color too few. If it’s not that, there must be some relationship between the colors and women. The women have all these colored veils, so I’m wondering if it’s a “Dance of the Seven Veils” thing. Should I take all the veils off? But the plural “veils” isn’t even recognized by the game. So, it can’t be that.

So, I brute-forced it. I put on a veil and went and offered a fig to the vizier. Nothing happened. Another veil. Nothing happened. Another veil. And something happened. I figure there must be a clue someplace telling what color of veil you’re supposed to wear. [4]The sultan’s vizier is suspected of having an affair with one of the wives in the sultan’s harem, and you’ve been charged with figuring out the facts of the case. The vizier is wearing a near-rainbow of colors on his person, while each of the six wives wears a veil corresponding to one of the colors he’s wearing. You need to disguise yourself in the veil of the wife with whom he’s having an affair, then go to him and give him a fig to signal a secret rendezvous later that night, thus setting up a chance for you to catch the two of them in flagrante delicto. That’s the easy part. The hard part is identifying which of the six veils to wear — i.e., identifying which is the wife he’s having the affair with before you actually catch them in the act.

There are two ways to “solve” this problem. Bob, and by all indications the vast majority of people who’ve ever played the game, treated it as a trial-and-error puzzle and brute-forced it, trying each veil in succession and restoring if it’s the wrong one. (Thank the stars it’s not randomized!) The “correct” solution is to lie on a divan in the area, whereupon all six women will give you a simultaneous massage, each choosing a different body part. (Hey, you… get your mind out of the gutter!) Only one wife is wearing a veil which corresponds to the color the vizier is wearing on her favored body part. She’s the guilty one. Why should this be? Well, we get into that very pertinent question later in the conversation…

Would you like me to tell you what the clue is?

Let me speculate just a little more.

Okay.

Are the colors the vizier is wearing relevant?

Yes. That’s key.

But it’s nothing to do with ROYGBIV?

No. It’s more devious than that.

Okay. Ohhh…. no, I don’t want you to tell me!

Should we table it until next time?

Yes. We’ll just mark it down for now as a bad puzzle.

For what it’s worth, that is in my opinion by far the worst puzzle in the game. That’s as bad as it gets.

So far, I agree with you. If I can figure out what I was thinking, I’ll let you know if I think it was a good idea or not. But right now, it seems kind of stupid. I probably only solved it because I have some trace memory of giving somebody a fig. But maybe I would have figured it out.

Giving him the fig isn’t the part that’s so problematic. The problem area is figuring out which of the veils to wear while you’re doing it. There’s one woman he’s having the affair with; you have to be wearing her veil. The very subtle clue tells you which woman’s veil you have to steal.

The puzzle’s only saving grace is that you can turn it into a save-and-restore puzzle, trying each veil in succession. But if you try the wrong veil — and there are six possibilities, so your first choice most likely will not be the right one — the game doesn’t give you any sign that you’re on the right track but just have the wrong veil. So, you’re likely to try something else rather than plow through all six veils by brute force.

Yeah. The only thing I can say in self-defense is that once you’re in there with the harem, you can’t escape back out until you solve the puzzle. Thank God for that! Otherwise, you’d think you had to go out and find some object. Any time I put a player in that kind of situation, it’s a strong indication that the puzzle is solvable from there. If they’re trapped somewhere, there should be a way out.

But I’ll try to figure it out, then we can talk more about it. There’s got to be some relation between what he’s wearing and which of the wives it is, but it certainly wasn’t obvious to me. I definitely brute-forced it.

Well, you’re on the right track.

That’s about all the questions I can ask you today without spoiling anything for you. Shall we reconvene in a week or so?

That sounds good. I’ve made pretty good progress with my lawn-mowering. My sense is that another several hours should do it.

Part 2: A triumphant Bob Bates celebrates having corrected the time stream — and without hints, as he is at pains to emphasize…

So! You finished, huh?

Yes, I finished.

Congratulations!

Thank you! And I’m happy to say that I finished without hints — mostly because I would have been horrifically embarrassed otherwise. But it was a close call. There were a couple of times I thought I was totally hosed. It was really only knowing myself that led me to the endgame. Here were all these places, and there were some that I’d blocked off, like modern-day Mexico. I’d obviously blocked them off because I didn’t want the player to go there and have nothing to do, which implied that there was something to do in every other place. And I knew I was missing a message. So, I thought, the way to attack this was to find a spot where nothing had happened and to pay really close attention.

That’s how I found the breeze in the Mexican temple — although if I’d been really on the ball I would have found it earlier. In that location in a previous time period, I’d noticed a place with reinforced walls. I should have marked that as an important spot. But then there was an interim time period where you could go to that spot and the passage up wasn’t there. That seems wrong. If they had planned it from the start with reinforced walls, that passage should have been there by the time they finished the temple. A minor point.

There were two puzzles in the game that I really didn’t care for. One we already discussed, but we should maybe discuss it a bit more now. That was of course the business in the harem. Did you ever work out where the missing clue was for that puzzle?

No, I didn’t have the time. I spent way too much time on solving the rest of the game. I thought that if I went back and looked carefully there would be some clue. I thought this even when I first encountered it. There must be something that the vizier does that creates a connection to one of the colors.

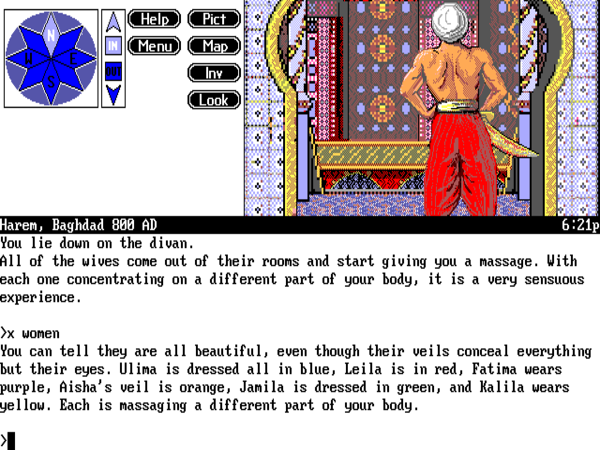

Okay. Let me try to remember and explain how this worked. Each woman in the harem is of course wearing a veil of a different color. If you lie on the divan there, they all come together to give you a massage — which sounds like something from a Spellcasting game rather than Timequest, but there you go.

Oh!

Did you not do that?

I did not.

Okay. Each woman massages a different body part.

I remember that! As soon as you mentioned the massage, I thought to myself that everyone would take a different body part.

You have to make note of what color goes with what body part.

Sure.

Oh, boy. I had this in my head ten days ago. Isn’t the vizier wearing some gloves?

He is.

And the gloves… I think they’re green?

I thought they were yellow…

Okay, that could be. But the woman that massaged your hands was wearing the same color as the vizier’s gloves. So you have to make a connection — which doesn’t really make a lot of sense — between the colors the women are wearing and the colors the vizier is wearing.

I thought it had something to do with the purple slipper. I ended up going through the entire game carrying a purple slipper.

Let me look in the hint book…

Okay, the gloves are actually green. The answer starts by saying, “This is pretty complicated”; the hint-book author must have been sneaking in a little design commentary. “The guilty wife is the one whose color matches the color of the piece of the vizier’s clothing that he wears on the part of the body she is massaging.” So, the vizier is described as dressed like a peacock, with all these different colors. If you compare the color of the woman who massages each body part to the color of that same body part on his clothing, the only one that matches is the hands with the green gloves. That’s the clue.

I’ll tell you what I think the problem with this puzzle is. I assumed that all players would lie on the divan — which, by the way, you can’t even call a “couch” or “bed” in the game. It’s the same problem as assuming that players will talk to all the characters, which is a huge problem in this game. Maybe in that era of game-making and game-playing you could assume that everybody would talk to every character, but I wouldn’t assume that today.

But once somebody lies on the divan, I’m not so upset with this puzzle. The words are very clear: “Each woman massages a different part of your body.” And when you look at one of them: “She’s covered from head to toe in a green veil. She is massaging your wrists and hands with a firm but feminine touch.” Once you’ve got all the women so specifically linked to a color and so specifically linked to a body part, then when you look at the picture of the vizier wearing colors that are so vivid and weird and out of place…

Well, I shouldn’t defend the puzzle, but I think the problem is not the connection between the colors. It’s needing the player to lie on the divan in the first place.

When I played I did lie on the divan, but I was nevertheless stumped by it. Some games deal in a very surreal or abstract sort of logic, but Timequest isn’t one of those games; it’s quite grounded. There’s usually very practical reasoning behind the puzzles. I don’t want to use the word “realistic” because it’s obviously not terribly realistic. But there’s a certain physicality to the logic. But this puzzle doesn’t have that sort of real-world logic behind it. Why should the woman wearing the color that corresponds with what the vizier is wearing on her favorite body part suddenly be the one who’s having the affair with him? It just strikes me as very obscure, and doesn’t fit with the style of the other puzzles in the game.

Yeah, I can see that. I’m sure my thinking was that the vizier and the woman wanted a secret way to signal to each other — a secret message between lovers. “We are aligned.” But yes, that’s too obscure.

The problem, then, is maybe that that doesn’t come through to the player. That happens sometimes to writers of adventure games. They have something in their head, but they don’t realize it’s not actually in the game — only in their head.

Yes. I would say that’s entirely accurate. There’s nothing that describes the color choice as a secret signal. Nothing leads you in that direction. I get that. It’s not well-constructed — and not well-explained afterwards.

Yeah, there’s only meta-logic or game logic to it. No real-world logic.

Yeah. The sultan could have said something like, “I’m sure these people have a way of signaling each other.” But that’s just not here.

When I was taking notes about the game, I said about this puzzle that it seemed like you just got a little bit too cute. You took things one level further than they needed to go. I think there’s the makings of a really good puzzle there, but it’s just a little bit too obscure.

I’d say it’s not well-grounded, which is kind of what you said before. And not well-communicated.

I’m astonished with this game, actually. One of the things I believe today, and thought I always believed, is that you should be able to figure out a good, fair puzzle without having to die to get information about it. Restore puzzles are bad! Well, my God… this game violates that principle up, down, left, and right. I’m really surprised at it.

The other puzzle I thought could have used a bit more of a nudge was the one that leads you into the endgame. You collect all these messages, then you have to arrange them in the order of the number that’s included in one way or another in each one, and then you have to take the first letter of each to learn the password to enter the endgame. As far as I know, nothing ever said that this was some sort of cryptographic puzzle. I was left at a loss. I had solved the whole game excepting the endgame, and I knew I had just one location left which I hadn’t done anything in, and I knew I needed a password of some sort there. And I knew all that had to involve these messages in some way. But it never really occurred to me to look at them in that way — to ask how I could find a secret message in them. I don’t think it’s necessarily as bad a puzzle as the harem puzzle, but that was the other place where I got stuck and had to go to the hints. Then all I needed was the nudge telling me there was a secret message hidden in there. As soon as I had that nudge, I figured it out quite quickly. I thought that nudge could maybe have been in the game proper without hurting things.

There actually is a nudge. It’s pretty subtle, and I won’t really defend it, but it is there. The sixth message to me, when I read it, leaped off the page like a trumpet call: “Numbers are important when you have no sixth sense and everything seems out of order.”

Okay. I did arrange them all in the correct order before I got the hint. But it never occurred to me to read the first character of each message.

Yeah. To any doer of British crosswords, this would have been second nature. To me, as soon as I knew there were many messages and that they were important, it was pretty clear what I needed to do.

One thing I’ve always hated in adventure games is riddles.

You and me both!

The reason I hate riddles is that you either get it or you don’t, and there’s no middle ground. If you don’t get it, it’s like a door slammed in your face. Your reaction to this strikes me as “riddleish.” Why should I look at the first letter? If I don’t know to do that, then I just don’t know to do that. And there’s nothing that tells you. The sixth clue says to put the messages in order. It would be good if something here said something like, “The thing that comes first is the most important.” It’s a case of a designer thinking that what he knows is known by everybody. The waters that I swim in are these kinds of puzzles. I stand guilty as charged of thinking something was obvious when it wasn’t.

It’s perhaps similar to the harem puzzle in that it feels kind of divorced from the game’s world, kind of abstract.

Well, I don’t agree with that totally. Clearly Zeke is taunting you, clearly he’s sending you messages, testing you. He’s challenging you to figure them out.

One interesting thing is that you can figure it out even if you don’t have all the messages. When I was missing the 17th message, I had “ZEKE IN TOWER, SAY E_ST.” Pretty clearly the password is “east.”

Yeah, I think that’s kind of a nice aspect of this puzzle. If you went through the whole game and somehow missed a few messages, you could still solve the puzzle and win the game.

Anyway, I liked the endgame proper a lot. Do you have any comments on that aspect of the game?

It seems to me that near the end of the game there should be a hard puzzle, kind of a capstone. In Timequest, that turned out to be what I think of as this nice little figure-eight, going backwards and forwards in time. It was difficult enough that I had to sit down and write it all out. It’s totally a restore puzzle, which is horrible. It was difficult, but it was nice.

Yeah. There is a difference, which many adventure-game designers fail to understand, between a fair but difficult puzzle and an unfair puzzle. Your final puzzle was difficult, but it was fair and satisfying to solve.

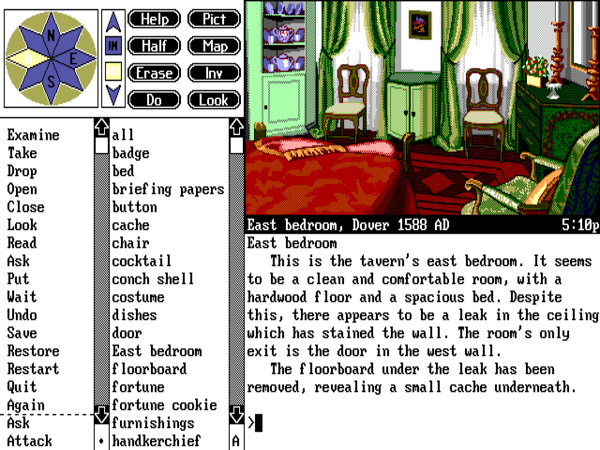

The final thing I’d like to talk about, that bothered me a little bit about the game, has nothing to do with the puzzles or even the design per se. I felt the game was a little lacking in atmosphere. Everybody that you meet, except I think for the people in Dover, speak a very flat, neutral American dialect of English. I think it was explained somewhere that you had some sort of translation technology, but in a lot of locations I just never felt much of a sense of place or even sense of history. This is something we kind of touched on last time we talked; the places that do that best tend to be the European locations. Rome was the best at it. Dover was pretty good too, although it was a little odd that they were talking in a sort of Cockney dialect in 1361 BC. And the pub there never changed, which could of course be read as a commentary on the nature of British pub life.

But some of the text in general…well, I say this because I’ve played your other games, and know you can write better descriptions than some of what is here. For instance, I’m looking at a screenshot here from the bedroom above the tavern in Dover in 1588 AD: “This is the tavern’s east bedroom. It seems to be a clean and comfortable room with a hardwood floor and a spacious bed. Despite this, there appears to be a leak in the ceiling which has stained the wall.” Why are we using these imprecise weasel verbs like “seems”? If I’m standing in a room looking around, does it “seem” to be clean and comfortable? Wouldn’t I know whether it’s clean and comfortable? Why does there “appear” to be a leak in the ceiling? Again, wouldn’t I know? I feel like the writing is generally stronger in your other games.

I think it’s basically a matter of skill — or a lack thereof — that breaks down into a couple of areas.

I just finished writing a novel that I started in 1995. One of the reasons it took so long to write — apart from the fact that there were big swathes of time when I had to set it aside — is that I’d send a rough draft to a reader, and they’d say, “It’s interesting, but I had some problems with it.” Two things I had to learn how to do over time.

One is exactly what you’re talking about: a sense of place. In the novel, I’d have a scene that might say, “So-and-so walks to the back of the church, kneels down, and starts to pray.” And then I’d go on from there. Readers would ask, “But what is the church like?” You know… it’s a church! Everybody knows what a church is like! It was only after being beaten over the head by many readers over a period of many years that I accepted that you have to describe the environment for the reader in such a way that they can picture it in their own mind. This was a problem for me because I don’t get pictures in my mind when I’m reading other people’s stuff. The author goes to great lengths to describe the environment, and I say, “Yeah, yeah, I get it. I’m in a church.” I don’t care. It doesn’t matter to me because I’m plot-driven.

So, as a creator, I didn’t think it was worth spending time on. But I learned that I had to say that it’s a dark church with the light filtering down from a window high on the wall, and you can see the dust motes in the air, and you can smell the incense, and you can hear the echoing footsteps, and so on. I think, okay, what can I do for sight? What can I do for sound? What can I do for smell? What can I do for touch? I run down this list. That’s something that took me years and years to learn how to do. Timequest was made well before I learned that lesson. And there are further lessons to be learned. One reader recently noted that I give sensual information, which is great, but I never interpret what it means to the character. Does he remember when he was a child in church? That’s a level of sophistication I haven’t yet gotten to. It’s a huge flaw in my writing, and certainly in the period of time of Timequest.

In Timequest, my goal was to impart the information the player needed to solve the puzzle. My first writing hero was E.B. White with his Elements of Style. Never put in a word that’s redundant or unnecessary.

When I was writing my game, I was very nervous about describing things too much because anything I described I had to implement.

Exactly! You say, “There’s a red wall here.” The player types, “look at red wall,” and gets back, “You don’t see any red wall here.” So, you say instead, “The room is the color of blood.” Anything to avoid having to implement an object that the player can try to interact with.

It’s a huge problem, and it’s made even worse in a game like Timequest with pictures. Then you have what I call the “farging artist problem.” The artist draws a window with curtains and pictures on the walls…

… and then everyone tries to “examine curtains.”

Exactly. So, you find yourself having to do a bunch of handling that you don’t want to do.

But that was just the first of your criticisms of the writing. The second one is also spot-on. During the last round of revisions of the novel, I realized that everybody in it sounded the same. That’s exactly what you just said about Timequest, and it’s entirely accurate. Maybe there are a couple of spots where I managed to give people a characteristic speaking style, but I’ll bet you that the priests in Mexico probably sound exactly the same as the Chinese emperors, who sound exactly the same as the Baghdad sultan. They probably all have the same freaking voice, which is this kind of pseudo-fantasy, formalized diction: “Here it is that I will go!” “I say this to you!” Again, it comes back to skill. I didn’t have the skill as a writer at that time in my life to even know that this was an issue.

Fair enough. The writing accomplishes what it needs to. It tells you everything you need to know, succeeds very well on a practical, game-playing level. But I could have used a little bit more of a sense of place and history. You don’t get as much of that as you maybe could.

Yeah. The history is present, but in a pretty unsatisfactory way. When you first come out in a new place, there’s a little lump of text which tells you what’s happened in this place since the last time period. Rome has fallen and is in disrepair, or the Mongols have taken over. There is that little paragraph to set the historical context.

But that’s telling, and I think the game needed a little bit more showing. The old cliché of creative writing that you always show and never tell isn’t really true, but you do have to have a balance.

But I think I’ve hit you with more than enough complaints by now. I don’t have too much else. Is there anything else you have to say about Timequest before we wrap up?

I guess I would just say that I tried.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t think the game is a disaster or anything…

No, I understand.

For every game I did at Legend, I remember feeling as we came down to the end that it was ripped out of my hands. There was always more that I wanted to do. But at the end it was always, “Bob, you have to stop. Step away from the keyboard!”

I think every game developer knows that feeling.

Yeah. I hauled out my time sheets from that period. There are some where I get to the office at 6:00 in the morning, leave at 8:00 the following morning. There’s this saying that an artist never finishes a painting, he only abandons it. That makes sense to me. The game isn’t done; you just have to stop.

We could say the same about this discussion, but it’s probably time to wrap it up. Thanks so much for doing this!

You’re more than welcome. And remember, point of pride: I solved it without hints!

I’m glad you’ll review the game before you share this conversation. There’s the thing as it stands, on its own, in the world. And then there’s something completely different: what was the guy trying to do, what did he have in mind, what did other people think, etc. Those are separate things.

Yeah, the criticism and the history.

Right. But thanks for your interest in it! And thanks for all the work you’re doing in this field.

And let’s see here… “Feel the wall”: “It feels just like you imagined a wall would feel.”

Well, at least it’s implemented.

Yeah! There you go!

You can download a copy of Timequest ready for playing under DOSBox from right here. And be sure to check out Bob Bates’s latest adventure Thaumistry: In Charm’s Way, a game guaranteed to be free of weasel verbs, die-and-restore puzzles, and weird fixations with the fashion accoutrements of ninth-century Baghdad.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Zeke Vettenmyer is the guy we’re chasing, the one who’s mucked up the time stream. The showdown with him will come in the endgame. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bob has hit upon the solution already. Each of the 19 messages has a number embedded within it in some fashion, from “Zeke is number one!” to “This is the last message I will leave you in the nineteen-hundreds.” First, you have to arrange the messages in numerical order; then, you have to read down the first letter of each message to learn the password to the endgame area. Bob and I will discuss this puzzle at more length — including why I don’t like it all that much — in our second chat. |

| ↑3 | The game just tells you that you can’t go there. |

| ↑4 | The sultan’s vizier is suspected of having an affair with one of the wives in the sultan’s harem, and you’ve been charged with figuring out the facts of the case. The vizier is wearing a near-rainbow of colors on his person, while each of the six wives wears a veil corresponding to one of the colors he’s wearing. You need to disguise yourself in the veil of the wife with whom he’s having an affair, then go to him and give him a fig to signal a secret rendezvous later that night, thus setting up a chance for you to catch the two of them in flagrante delicto. That’s the easy part. The hard part is identifying which of the six veils to wear — i.e., identifying which is the wife he’s having the affair with before you actually catch them in the act.

There are two ways to “solve” this problem. Bob, and by all indications the vast majority of people who’ve ever played the game, treated it as a trial-and-error puzzle and brute-forced it, trying each veil in succession and restoring if it’s the wrong one. (Thank the stars it’s not randomized!) The “correct” solution is to lie on a divan in the area, whereupon all six women will give you a simultaneous massage, each choosing a different body part. (Hey, you… get your mind out of the gutter!) Only one wife is wearing a veil which corresponds to the color the vizier is wearing on her favored body part. She’s the guilty one. Why should this be? Well, we get into that very pertinent question later in the conversation… |