The first CRPG to go online appeared on The Source, CompuServe’s most prominent early competitor. Black Dragon, written by a programmer of telephone switching systems named Bob Maples, was at bottom a simplified version of Wizardry — not a hugely surprising state of affairs, given that it made its debut in 1981, at the height of the Wizardry craze. The player created a character — just one, not a full party as in Wizardry — and then began a series of expeditions into the game’s ten-level labyrinth, fighting monsters, collecting equipment and experience, and hopefully penetrating a little deeper with each outing. Only the character’s immediate surroundings were described on the scrolling, text-only display, so careful mapping became every bit as critical as it was in Wizardry. The ultimate goal, guaranteed to consume many hours — not to mention a small fortune in connection charges — was to kill Asmodeus, the black dragon of the title, who lurked down on the tenth level. Any player who managed to accomplish that feat and escape back to the surface was rewarded by seeing her name along with her character’s immortalized on the game’s public wall of fame.

Those bragging rights aside, Black Dragon had no multiplayer aspect at all, which might lead one to ask why its players didn’t just pick up a copy of Wizardry instead; doing so would certainly have been cheaper in the long run. But the fact is that not every Source subscriber’s computer could run Wizardry in those early days. Certainly Black Dragon proved quite popular as the first game of its kind. Sadly lost to history now, it has been described by some of its old players as far more cleverly designed than its bare-bones presentation and its willingness to unabashedly ride Wizardry‘s coattails might lead one to believe.

Bill Louden, the “games guy” over at CompuServe, naturally followed developments on The Source closely. The success of Black Dragon led him to launch a somewhat more sophisticated single-player CRPG in 1982. Known as Dungeons of Kesmai, it was, as the name would imply, another work of the indefatigable John Taylor and Kelton Flinn — i.e., Kesmai, the programmers also responsible for CompuServe’s MegaWars III and, a bit later, for GEnie’s Air Warrior. Like so many of CompuServe’s staple games, Dungeons of Kesmai would remain on the service for an absurdly long time, until well into the 1990s.

But more ambitious games as well would come down the pipe well before then. A few years later after these first single-player online CRPGs debuted, CompuServe made the leap to multiplayer virtual worlds. As we’ve already seen in my previous article, MUD washed up from British shores in the spring of 1986 under the name of British Legends, bringing with it the idea of the multiplayer text adventure as virtual world. Yet even before that happened, in December of 1985, the CRPG genre had already made the same leap thanks to still another creation from Kesmai: Island of Kesmai.

Taylor and Flinn had originally hoped to make Dungeons of Kesmai something akin to the game which Island would later become, but that project had been cut back to a single-player game when Bill Louden deemed it simply too ambitious for such an early effort. Undaunted, Kesmai treated Dungeons as a prototype for their real vision for a multiplayer CRPG and just kept plugging away. They never saw nor heard of MUD when developing the more advanced game, meaning that said game’s innovations, which actually hew much closer than MUD to the massively-multiplayer games to come, were all its own.

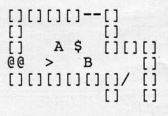

Island of Kesmai demonstrated just how far games’ presentation had come on CompuServe in the three years of creeping advancement that had followed Dungeons of Kesmai. While it was still limited to text and crude character graphics, the latest terminal protocols did allow it to make use of color, and to divide the screen into quadrants dedicated to different purposes: a status “window” showing the state of the player’s character, a pseudo-graphical overhead view of the character’s surroundings, a text area for descriptions of the environment, a command line for the player to issue orders. Island of Kesmai looked like a roguelike, a genre of hardcore tactical CRPG that was a bigger favorite with hackers than with commercial game developers. This roguelike, however, was a multiplayer game set in a persistent world, and that changed everything.

Island of Kesmai used the ASCII graphics typical of roguelikes. Here “>” represents the player’s character; “A” is a monster; “B” is another player’s character; “@@” is a spider web; and “$” is a treasure or other item. The brackets are walls, while “–” represents a closed door and “/” an open one.

As with British Legends, up to 100 players could share Island of Kesmai‘s persistent world at the same time. Yet Kesmai’s creation was a far more coherent, far more designed experience than the cheerful insanity that was life on MUD. Players chose a class for their characters, along with an alignment, a gender, and even a land of origin. As befitted the game’s grounding in CRPG rather than text-adventure tradition, combat was a far more elaborate and tactical affair than in MUD. You had to reckon with the position of your character and your opponents; had to worry about initiative and fatigue; could be stunned or poisoned or even fumble your weapon. The magic system, too, was far more advanced and subtle than MUD‘s handful of ad-hoc spells that had often been added as much for comedic value as anything else.

The Island that gave the game its name was divided into five regions, comprising in total some 62,000 discrete locations, over which roamed some 2500 creatures in addition to one’s fellow players. The game was consciously designed to support differing levels of player engagement. “A person can play casually or seriously,” said Ben Shih, a “scenario designer” hired by Kesmai to continue evolving the game. “He or she can relax and take out frustrations on a few goblins or unwind by joining other players in hunting bear and griffin. But to become a superstar, a ‘mega-character,’ takes time.”

Scenario designers like Shih added content on a regular basis to keep the game fresh even for veteran players, sometimes giving a unique artifact to the first player to complete a new quest. Kelton Flinn was still excited about adding new stuff to the game three years after it had first gone online:

We don’t feel we’re designing games. We’re designing simulations. We create a world and then we let the players roam around in it. Of course, we’re always adding to our view of the world, fiddling with things all the time, creating new treasures, making things work better. I suppose at some point you have to call a halt and say, “Let’s see if we want to make a clean break and try something bigger.” But we haven’t reached that stage yet.

For all the changes the game went through, the ultimate achievement in Island of Kesmai remained always to kill the dragon, the toughest monster in the game. Players who did so were rewarded with everlasting fame as part of the true elite. As for the dragon: he of course re-spawned in a few days’ time, ready to serve as fodder for the next champion.

Those who hoped to do well were almost forced to buy the 181-page manual for the game, available for the low, low price of $16.50 directly from CompuServe. A rather stunning percentage of the elements described therein would still ring true to any World of Warcraft player of today. There was, for instance, a questing system, a ladder of challenges offering ever greater rewards in return for surviving ever greater dangers. Even those looking for an equivalent to the endless stream of World of Warcraft expansions can find it with Island of Kesmai. In 1988, Kesmai opened up the new lands of Torii and Annwn, filled with “more powerful weapons, tougher monsters, and a variety of treasures.” Advanced players were allowed to travel there only after their characters had hit the old Island’s level cap, and weren’t allowed to return again after they passed through the magic portal, lest they wreak havoc among the less powerful monsters and characters they once left behind.

While play on the Island was much more structured than it was in The Land of MUD, it was still the other players who really made the game what it was. Taylor and Flinn went into the project understanding that, and even anticipating to an extraordinary degree the shape of virtual societies to come. “We fully expect that a political system will evolve,” said Taylor upon the game’s launch, “and someone may even try to proclaim himself King of Kesmai.” Much of the design was put in place to emphasize the social aspect of the game. For example, a conference room was provided for strategizing and conspiring, and many quests were deliberately designed to require the cooperation of several characters. The verbiage adopted by players in relation to the quest system still rings true to modern ears. For example, a verb was coined for those loners determined to undertake quests on their own: to “solo.”

Although player-versus-player combat was allowed, it was restricted to specific areas of the Island; an attempt to attack another character in a “civilized” area, such as the town where new players began their adventures, would be met by the Sheriff, an invincible non-player character guaranteed to grind the brawniest hero into dust. Alignment also played a role: a karma meter kept track of players’ actions. Actions like assault or theft would gradually turn a good character neutral, then finally evil. The last alignment was highly undesirable from many perspectives, not least in that it would prevent you from entering the town, with its shops, bars, and trainers.

And there were still other mechanisms for discouraging the veterans from tormenting the newbies in the way so many MUD players so enjoyed. Players were urged to report griefers who preyed excessively upon newbies, even if they only did so in the dungeons and other “uncivilized” areas where player-versus-player combat was technically allowed. If enough people lodged complaints against them, the griefers might find themselves visited by the wrath of the “ghods of Kesmai,” the game’s administrators — the alternate spelling was used so as not to offend the religious — who might take away experience points, steal back their precious magic items, or just smite them dead as punishment. The game thus tended to foster a less cutthroat, more congenial atmosphere than MUD, with most players preferring to band together against the many monsters rather than fight with one another.

A journalist from the magazine Compute’s Gazette shared this tale of his own almost unbelievably positive first encounter with another player in the game:

I desperately wish I could afford to buy a few bottles of balm sold by the vendor here in the nave, but at 16 gold pieces each they are far above my limited budget. Another player walks in from the square. “Hello, Cherp!” she says, looking at me. Taking a close look at her, I recognize Lynn, a middle-aged female fighter from my home country of Mnar.

“Howdy to you. Are you headed down into the dungeon? I’ve just arrived and this is my first trip down,” I tell her.

“Ah, I see. Yes, I was headed down, but I don’t think it’s safe for you to hunt where I’ll be going. Do you have any balm yet?” she asks as she stands next to the balm vendor.

“No, I haven’t got the gold to afford it,” I say hesitantly.

“No problem. I have a few extra pieces. Come and get them.”

“Thank you very much,” I say. Lynn drops some gold on the ground, and we wait as the vendor takes the gold and drops the balm bottles for us. I pick up the bottles and add them to my meager possessions.

“I can’t thank you enough for this,” I say. “Is there some way I can repay you? Perhaps we could meet here again later and I could give you some balms in return.”

“No,” she laughs, “I have no need of them. Just remember there are always other players who are just starting out. They may find themselves in the same position you are in now. Try to lend them a hand when you are sufficiently strong.”

At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, I will just note one more time that this attitude stands in marked contrast to the newbie-tormenting that the various incarnations of MUD always seemed to engender. At least one player of Island of Kesmai so distinguished himself through his knowledge of the game and his sense of community spirit that he was hired by Kesmai to design new challenges and serve as a community liaison — a wiz mode of a different and much more lucrative stripe.

But the community spirit of Island of Kesmai at its finest is perhaps best exemplified by Valis, one of the game’s most accomplished players. This online CRPG was actually the first RPG of any stripe he had ever managed to enjoy, despite attending university during the height of the Dungeons & Dragons fad: “I could never get into sitting around eating crackers and cheese doodles and arguing for twelve hours at a time. I can do as much in a half hour in Island of Kesmai as they did in twelve hours.” Valis became the first person to exhaustively map the entire Island, uploading the results to the service’s file libraries for the benefit of all. Further, he put together a series of beginners classes for those new to what could be a very daunting game. CompuServe’s hapless marketers advertised his efforts as an “escort service,” a name which perhaps didn’t convey quite the right impression.

We think we’ve come up with the perfect way of teaching a beginners class. We spend an hour or so in the conference area with a lecture and questions. Then we go on a “field trip” to the Island itself. I lead the beginners onto the Island, where we encounter a few things and look for some treasure. That usually is enough to get them started.

In many respects, the personal stories that emerged from Island of Kesmai will ring very familiar to anyone who’s been reading my recent articles, as they will to anyone familiar with the massively-multiplayer games of today. Carrie Washburn discovered the game in 1986, just after her son was born fourteen weeks premature. During the months the baby spent in intensive care, Island of Kesmai became the “link back to reality” for her and her husband. After spending the day at the hospital, they “would enter a fantasy world in order to forget the real one. The online friends that we met there helped pull us through.” Of course, the escape wasn’t without cost: Washburn’s monthly CompuServe bill routinely topped $500, and once hit $2000. Later she divorced her husband and took to prancing around the Island as the uninhibited Lynn De’Leslie — “more of a slut, really” — until she met her second husband there. Her sentiments about it all echoed those expressed by the CB Simulator fraternity on another part of CompuServe: “One of the great things about meeting people online is that you get to really know them. The entire relationship is built on talking.” (Appropriately enough for a talker, Washburn went on to find employment as the administrator of the Multiplayer Games Roundtable on GEnie.)

Kelton Flinn once called Island of Kesmai “about as complicated as a game can be on a commercial system.” Yet it deserves to be remembered for the thought that went into it even more than for its complexity. Almost every issue that designers of the massively-multiplayer games of today deal with was anticipated and addressed by Kesmai — sometimes imperfectly, yes, but then many of the design questions which swirl around the format have arguably still not been met with perfect answers even today. Incredibly, Island of Kesmai went online in December of 1985 with almost all of its checks and balances already in place, so thoroughly had its designers thought about what they were creating and where it would lead. To use Richard Bartle’s terminology from my previous article, Island of Kesmai was a “product” rather than a “program,” and it was all the better for it. While MUD strikes me as a pioneering work with an awful lot of off-putting aspects, such that I probably wouldn’t have lasted five minutes if I’d stumbled into it as a player, Island of Kesmai still sounds like it must have been fantastic to play.

One big name in the field of single-player graphical CRPGs took note of what was going on on The Island quite early. In 1987, a decade before Ultima Online would take the games industry by storm, Richard Garriott and Origin Systems began doing more than just muse about the potential for a multiplayer Ultima. They assigned at least one programmer to work full-time on the technology that could enable just such a product. This multiplayer Ultima was envisioned on a more modest scale than the eventual Ultima Online or even the current Island of Kesmai. It was described by Garriott thus: “What you’ll buy in the store will be a package containing all the core graphics routines and the game-development stuff (all the commands and so on), which you could even plug into your computer and play as a standalone. But with a modem you could tie a friend into the game, or up to somewhere between eight and sixteen other players, all within the same game.” Despite the modest number of players the game would support and the apparent lack of plans for a persistent world, Origin did hold out the prospect of a partnership with CompuServe. In the end, though, none of it went anywhere. After 1987 the idea of a multiplayer Ultima was shelved for a long, long time; Origin presumably deemed it too much of a distraction from their bread-and-butter single-player CRPG franchise.

Another of the big single-player CRPG franchises, however, would make the leap — and not just to multiplayer but all way to a persistent virtual world like that of MUD or Island of Kesmai. Rather than running on the industry-leading CompuServe or even the gamer haven of GEnie, this pioneering effort would run on the nascent America Online.

Don Daglow was already a grizzled veteran of the games industry when he founded a development company called Beyond Software (no relation to the British company of the same name) in 1988. He had programmed games for fun on his university’s DEC PDP-10 in the 1970s, programmed them for money at Intellivision in the early 1980s, been one of the first producers at Electronic Arts in the mid-1980s — working on among other titles Thomas M. Disch’s flawed but fascinating text adventure Amnesia and the hugely lauded baseball simulation Earl Weaver Baseball — and finally came to spend some time in the same role at Brøderbund. At last, though, he had “got itchy” to do something that would be all his own. Beyond was his way of scratching that itch.

Thanks to Daglow’s industry connections, Beyond hit the ground running, establishing solid working relationships with two very disparate companies: Quantum Computer Services, who owned and operated America Online, and the boxed-game publisher SSI. Daglow actually signed on with the former the day after forming his company, agreeing to develop some simple games for their young online service which would prove to be the very first Beyond games to see the light of day. Beyond’s relationship with the latter would lead to the publication of another big-name-endorsed baseball simulation: Tony La Russa’s Ultimate Baseball, which would sell an impressive 85,684 copies, thereby becoming SSI’s most successful game to date that wasn’t an entry in their series of licensed Dungeons & Dragons games.

As it happened, though, Beyond’s relationship with SSI also came to encompass that license in fairly short order. They contracted to create some new Dungeons & Dragons single-player CRPGs, using the popular but aging Gold Box engine which SSI had heretofore reserved for in-house titles; the Beyond games were seen by SSI as a sort of stopgap while their in-house staff devoted themselves to developing a next-generation CRPG engine. Beyond’s efforts on this front would result in a pair of titles, Gateway to the Savage Frontier and Treasures of the Savage Frontier, before the disappointing sales of the latter told both parties that the jig was well and truly up for the Gold Box engine.

By Don Daglow’s account, the first graphical multiplayer CRPG set in a persistent world was the product of a fortunate synergy between the work Beyond was doing for AOL and the work they were doing for SSI.

I realized that I was doing online games with AOL and I was doing Dungeons & Dragons games with SSI. Nobody had done a graphical massively-multiplayer online game yet. Several teams had tried, but nobody had succeeded in shipping one. I looked at that, and said, “Wait, I know how to do this because I understand how the Dungeons & Dragons system works on the one hand, and I understand how online works on the other.” I called up Steve Case [at AOL], and Joel Billings and Chuck Kroegel at SSI, and said, “If you guys want to give it a shot, I can give you a graphical MMO, and we can be the first to have it.”

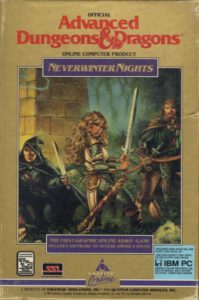

The game was christened Neverwinter Nights. “Neverwinter” was the area of the Forgotten Realms campaign setting which TSR, makers of the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop RPG, had carved out for Beyond to set their games; the two single-player Savage Frontier games were also set in the region. The “Nights,” meanwhile, was a sly allusion to the fact that AOL — and thus this game — was only available on nights and weekends, when the nation’s telecommunications lines could be leased relatively cheaply.

Neverwinter Nights had to be purchased as a boxed game before players could start paying AOL’s connection fees to actually play it. It looked almost indistinguishable from any other Gold Box title on store shelves — unless one noticed the names of America Online and Quantum Computer Services in the fine print.

On the face of it, Neverwinter Nights was the ugliest of kludges. Beyond took SSI’s venerable Gold Box engine, which had never been designed to incorporate multiplayer capabilities, and grafted exactly those capabilities onto it. At first glance, the end result looked the same as any of the many other Gold Box titles, right down to the convoluted interface that had been designed before mice were standard equipment on most computers. But when you started to look closer, the differences started to show. The player now controlled just one character instead of a full party; parties were formed by multiple players coming together to undertake a quest. To facilitate organizing and socializing, a system for chatting with other players in the same map square had been added. And, in perhaps the trickiest and certainly the kludgiest piece of the whole endeavor, the turn-based Gold Box engine had been converted into a pseudo-real-time proposition that worked just well enough to make multiplayer play possible.

It made for a strange hybrid to say the least — one which Richard Bartle for one dismisses as “innovative yet flawed.” Yet somehow it worked. After launching the game in June of 1991 with a capacity of 100 simultaneous players, Beyond and AOL were soon forced by popular demand to raise this number to 500, thus making Neverwinter Nights the most populous virtual world to go online to date. And even at that, there were long lines of players during peak periods waiting for others to drop out of the game so they could get into it, paying AOL’s minute-by-minute connection fee just to stand in the queue.

While players and would-be players of online CRPGs had undoubtedly been dreaming of the graphics which Neverwinter Nights offered for a long time, smart design was perhaps equally important to the game’s long-term popularity. To an even greater degree than Island of Kesmai, Neverwinter Nights strove to provide a structure for play. Don Daglow had been interested in online gaming for a long time, had played just about all of what was available, and had gone into this project with a clear idea of exactly what sort of game he wanted Neverwinter Nights to be. It was emphasized from the get-go that this was not to be a game of direct player-versus-player conflict. In fact, Beyond went even Kesmai one better in this area, electing not just to ban such combat from certain parts of the game but to ban it entirely. Neverwinter Nights was rather to be a game of cooperation and friendly competition. Players would meet on the town’s central square, form themselves into adventuring parties, and be assigned quests by a town clerk — shades of the much-loved first Gold Box game, Pool of Radiance — to kill such-and-such a monster or recover such-and-such a treasure. Everyone in the party would then share equally in the experience and loot that resulted. Even death was treated relatively gently: characters would be revived in town minus all of the stuff they had been toting along with them, but wouldn’t lose the armor, weapons, and magic items they had actually been using — much less lose their lives permanently, as happened in MUD.

One player’s character has just cast feeblemind on another’s, rendering him “stupid.” This became a sadly typical sight in the game.

Beyond’s efforts to engender the right community spirit weren’t entirely successful; players did find ways to torment one another. While player characters couldn’t attack one another physically, they could cast spells at one another — a necessary capability if a party’s magic-using characters were to be able to cast “buffing” spells on the fighters before and during combat. A favorite tactic of the griefers was to cast the “feeblemind” spell several times in succession on the newbies’ characters, reducing their intelligence and wisdom scores to the rock bottom of 3, thus making them for all practical purposes useless. One could visit a temple to get this sort of thing undone, but that cost gold the newbies didn’t have. By most accounts, there was much more of this sort of willful assholery in Neverwinter Nights than there had been in Island of Kesmai, notwithstanding the even greater lengths Beyond had gone to prevent it. Perhaps it was somehow down to the fact that Neverwinter Nights was a graphical game — however crude the graphics were even by the standards of the game’s own time — that led to it attracting a greater percentage of such immature players.

Griefers aside, though, Neverwinter Nights had much to recommend it, as well as plenty of players happy to play it in the spirit Beyond had intended. Indeed, the devotion the game’s most hardcore players displayed remains legendary to this day. They formed themselves into guilds, using that very word for the first time to describe such aggregations. They held fairs, contests, performances, and the occasional wedding. And they started at least two newsletters to keep track of goings-on in Neverwinter. Some issues have been preserved by dedicated fans, allowing us today a glimpse into a community that was at least as much about socializing and role-playing as monster-bashing. The first issue of News of the Realm, for example, tells us that Cyric has just become a proud father in the real world; that Vulcan and Dramia have opened their own weapons shop in the game; that Cold Chill the notorious bandit has shocked everyone by recognizing the errors of his ways and becoming good; that the dwarves Nystramo and Krishara are soon to hold their wedding — or, as dwarves call it, their “Hearth Building.” Clearly there was a lot going on in Neverwinter.

The addition of graphics would ironically limit the lifespan of many an online game; while text is timeless, computer graphics, especially in the fast-evolving 1980s and 1990s, had a definite expiration date. Under the circumstances, Neverwinter Nights had a reasonably long run, remaining available for six years on AOL. Over the course of that period online life and computer games both changed almost beyond recognition. Already looking pretty long in the tooth when Neverwinter Nights made its debut in 1991, the Gold Box engine by 1997 was a positive antique.

Despite the game’s all-too-obvious age, AOL’s decision to shut it down in July of 1997 was greeted with outrage by its rabid fan base, some of whom still nurse a strong sense of grievance to this day. But exactly how large that fan base still was by 1997 is a little uncertain. The Neverwinter Nights community insisted (and continues to insist) that the game was as popular as ever, making the claim from uncertain provenance that AOL was still making good money from it. Richard Bartle makes the eye-popping claim today, also without attribution, that it was still bringing in fully $5 million per year. Yet the reality remains that this was an archaic MS-DOS game at a time when software in general had largely completed the migration to Windows. It was only getting more brittle as it fell further and further behind the times. Just two months after the plug was pulled on Neverwinter Nights, Ultima Online debuted, marking the beginning of the modern era of massively-multiplayer CRPGs as we’ve come to know them today. Neverwinter Nights would have made for a sad sight in any direct comparison with Ultima Online. It’s understandable that AOL, never an overly games-focused service to begin with, would want to get out while the getting was good.

Even in its heyday, when the land of Neverwinter was stuffed to its 500-player capacity every night and more players were lining up outside, its popularity was never all that great in the grand scheme of the games industry; that very capacity limit if nothing else saw to that. Nevertheless, its place in gaming lore as a storied pioneer was such that Bioware chose to revive the name in 2002 in the form of a freestanding boxed CRPG with multiplayer capabilities. That version of Neverwinter Nights was played by many, many times more people than the original — and yet it could never hope to rival its predecessor’s claim to historical importance.

The massively-multiplayer online CRPGs that would follow the original Neverwinter Nights would be slicker, faster, in some ways friendlier, but the differences would be of degree, not of kind. MUD, Island of Kesmai, and Neverwinter Nights between them had invented a genre, going a long way in the process toward showing any future designers who happened to be paying attention exactly what worked there and what didn’t. All that remained for their descendants to do was to popularize it, to make it easier and cheaper and more convenient to lose oneself in a shared virtual world of the fantastic.

(Sources: the books MMOs from the Inside Out by Richard Bartle and Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsey; Online Today of February 1986, April 1986, August 1986, June 1987, January 1988, August 1988, September 1988, and February 1989; Computer Gaming World of June/July 1986; The Gamers Connection of September/October 1988; Compute!’s Gazette of July 1989; Compute! of November 1991; the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Online sources include Barbara Baser’s Black Dragon walkthrough, as preserved by Arthur J. O’Dwyer; “The Game Archaeologist Discovers the Island of Kesmai” from Engadget. Readers may also be interested in the CRPG Addict’s more experiential impression of playing Neverwinter Nights offline — and be sure to check out the comments to that article for some memories of old players.)