The die for the first successful incarnation of Psygnosis was cast in the summer of 1987 with the release of a game called Barbarian. It was actually the company’s fourth game, following Brataccas, that underwhelming fruition of Imagine Software’s old megagame dream, and two other titles which had tried to evoke some of the magic of games from other publishers and rather resoundingly failed: Arena, an unfun alternative to the Epyx Games sports series, and Deep Space, a vaguely Elite-like game of interstellar trading and space combat saddled with a control scheme so terrible that many buyers initially thought it was a bug. None of this trio, needless to say, had done much for Psygnosis’s reputation. But with Barbarian the company’s fortunes finally began to change. It provided them at last with just the formula for commercial success they had been so desperately seeking.

Programmed by the redoubtable Dave Lawson, Barbarian might be labeled an action-adventure if we’re feeling generous, although it offers nothing like the sort of open-ended living world other British developers of the era were creating under that label. It rather takes the form of a linear progression through a series of discrete screens, fighting monsters and dodging traps as the titular barbarian Hegor. The control scheme — for some reason a consistent sore spot in almost every game Lawson programmed — once again annoys more than it ought to, and the game as a whole is certainly no timeless classic. What it did have going for it back in the day, however, were its superb graphics and sound. Released initially only on the Atari ST and the Commodore Amiga, just as the latter especially was about to make major inroads in Britain and Europe thanks to the new Amiga 500 model, it was one of the first games to really show what these 16-bit powerhouses could do in the context of a teenage-boy-friendly action game. Reviewers were so busy gushing about the lengthy opening animation, the “strange-looking animals,” and the “digitised groans and grunts” that accompanied each swing of Hegor’s sword as he butchered them that they barely noticed the game’s more fundamental failings.

Barbarian became the first unadulterated, undeniable hit to be created by the Imagine/Psygnosis nexus since Dave Lawson’s Arcadia had kicked everything off on the Sinclair Spectrum almost five years before. Thus was a precedent set. Out were the old dreams of revolutionizing the substance of gaming via the megagame project; in were simple, often slightly wonky action games that looked absolutely great to the teenage boys who devoured them. If Lawson and Ian Hetherington were disappointed to have abandoned more high-concept fare for simple games with spectacular visuals, they could feel gratified that, after all the years of failure and fiasco as Imagine, Finchspeed, Fireiron, and finally Psygnosis, they were at last consistently making games that made them actual money.

Psygnosis’s first games had been created entirely in-house, with much of the design and coding done by Lawson and Hetherington themselves. In the wake of Barbarian‘s success, however, that approach was changed to prioritize what was really important in them. After the games already in the pipeline at the time of Barbarian‘s release were completed, future programming and design — such as the latter was in the world of Psygnosis — would mostly be outsourced to the hotshot young bedroom coders with which Britain was so amply endowed.

Psygnosis hired far more artists rather than programmers as in-house employees. They built an art team that became the envy of the industry around one Garvan Corbett, a talented illustrator and animator who had come to Psygnosis out of a workfare program in the very early days, before even Brataccas had been released, and who had been responsible for the precedent-setting graphics in Barbarian. Notably, none of Psygnosis’s artists had much prior experience with computers; the company preferred to hire exceptional artists in traditional mediums and teach them what they needed to know to apply their skills to computer games. It gave Psygnosis’s games a look that was, if not quite what one might describe as more mature than the rest of the industry, certainly more striking, more polished. Working with Amigas running the games-industry stalwart Deluxe Paint, Corbett and his colleagues would build on the submissions of the outside teams to bring them in line with Psygnosis’s house style, giving the in-game graphics that final sheen for which the company was so famous whilst also adding the elaborate title screens and opening animations for which they were if anything even more famous. Such a hybrid of in-house and out-of-house development was totally unique in late-1980s game-making, but it suited Psygnosis’s style-over-substance identity perfectly. “At Psygnosis, graphics are all-important,” wrote one journalist as his final takeaway after a visit to the company. Truer words were never written.

With the assistance of an ever-growing number of outside developers, the games poured out of Psygnosis in the years after Barbarian, sporting short, punchy titles that sounded like heavy-metal bands or Arnold Schwarzenegger movies, both of which things served as a profound influence on their young developers: Terrorpods, Obliterator, Menace, Baal, Stryx, Blood Money, Ballistix, Infestation, Anarchy, Nitro, Awesome, Agony. Occasionally Psygnosis would tinker with the formula, as when they released the odd French adventure game Chrono Quest, but mostly it was nothing but relentless action played over a relentlessly thumping soundtrack. An inordinate number of Psygnosis games seemed to feature tentacled aliens that needed to be blown up with various forms of lasers and high explosives. In light of this, even the most loyal Psygnosis fan could be forgiven for finding it a little hard to keep them all straight. Many of the plots and settings of the games would arrive on the scene only after the core gameplay had been completed, when Psygnosis’s stable of artists were set loose to wrap the skeletons submitted by the outside developers in all the surrealistic gore and glory they could muster. Such a development methodology couldn’t help but lend the catalog as a whole a certain generic quality. Yet it did very, very well for the company, as the sheer number of games they were soon churning out — nearly one new game every other month by 1989 — will attest.

Psygnosis’s favored machine during this era was the Amiga, where their aesthetic maximalism could be deployed to best effect. They became known among owners of Amigas and those who wished they were as the platform’s signature European publisher, the place to go for the most impressive Amiga audiovisuals of all. This was the same space occupied by Cinemaware among the North American publishers. It thus makes for an interesting exercise to compare and contrast the two companies’ approaches.

In the context of the broader culture, few would have accused Cinemaware’s Bob Jacob, a passionate fan of vintage B-movies, of having overly sophisticated tastes. Yet, and often problematic though they admittedly were in gameplay terms, Cinemaware’s games stand out next to those of Psygnosis for the way they use the audiovisual capabilities of the Amiga in the service of a considered aesthetic, whether they happen to be harking back to the Robin Hood of Errol Flynn in Defender of the Crown or the vintage Three Stooges shorts in the game of the same name. There was a coherent and unique-to-it sense of aesthetic unity behind each one of Cinemaware’s games, as indicated by the oft-mocked title Jacob created for the person tasked with bringing it all together: the “computographer,” who apparently replaced the cinematographer of a movie.

Psygnosis games, in contrast, had an aesthetic that could be summed up in the single word “more”: more explosions, more aliens, more sprites flying around, more colors. This was aesthetic maximalism at its most maximalist, where the impressiveness of the effect itself was its own justification. Psygnosis’s product-development manager John White said that “half the battle is won if the visuals are interesting.” In fact, he was being overly conservative in making that statement; for Psygnosis, making the graphics good was actually far more than half the battle that went into making a game. Ian Hetherington:

We always start with a technical quest — achieving something new with graphics. We have to satisfy ourselves that what we are trying to achieve is possible before we go ahead with a game. My worst moments are when I show innovative techniques to the Japanese, and all they want to know is, what is the plot. They don’t understand our way of going about things.

The Japanese approach, as practiced by designers like the legendary Shigeru Miyamoto, would lead to heaps of Nintendo Entertainment System games that remain as playable today as they were in their heyday. The Psygnosis approach… not so much. In fact, Psygnosis’s games have aged almost uniquely poorly among their peers. While we can still detect and appreciate the “computography” of a Cinemaware interactive movie, Psygnosis games hit us only with heaps of impressive audiovisual tricks that no longer impress. Their enormous pixels and limited color palettes — yes, even on an audiovisual powerhouse of the era like the Amiga — now make them look quaint rather than awe-inspiring. Their only hope to move us thus becomes their core gameplay — and gameplay wasn’t one of Psygnosis’s strengths. Tellingly, most Psygnosis games don’t sport credited designers at all, merely programmers and artists who cobbled together the gameplay in between implementing the special effects. An understanding of what people saw in all these interchangeable games with the generic teenage-cool titles therefore requires a real effort of imagination from anyone who wasn’t there during the games’ prime.

The success of Psygnosis’s games was inextricably bound up with the platform patriotism that was so huge a part of the computing scene of the 1980s. What with the adolescent tendency to elevate consumer lifestyle choices to the status of religion, the type of computer a kid had in his bedroom was as important to his identity as the bands he liked, the types of sports cars he favored, or the high-school social set he hung out with — or possibly all three combined. Where adults saw just another branded piece of consumer electronics, he saw a big chunk of his self-image. It was deeply, personally important to him to validate his choice by showing off his computer to best effect, preferably by making it do things of which no other computer on the market was capable. For Amiga owners in particular, the games of Psygnosis fulfilled this function better than those of any other publisher. You didn’t so much buy a Psygnosis game to play it as you did to look at it, and to throw it in the face of any of your mates who might dare to question the superiority of your Amiga. A Psygnosis game was graphics porn of the highest order.

But Psygnosis’s graphics-über-alles approach carried with it more dangers than just that of making games whose appeal would be a little incomprehensible to future generations. Nowhere was the platform patriotism that they traded on more endemic than in the so-called “scene” of software piracy, whose members had truly made the computers they chose to use the very center of their existence. And few games were more naturally tempting targets for these pirates than those of Psygnosis. After all, what you really wanted out of a Psygnosis game was just a good look at the graphics. Why pay for that quick look-see when you could copy the disk for free? Indeed, cracked versions of the games were actually more appealing than the originals in a way, for the cracking groups who stripped off the copy protection also got into the habit of adding options for unlimited lives and other “trainers.” By utilizing them, you could see everything a Psygnosis game had to offer in short order, without having to wrestle with the wonky gameplay at all.

It was partially to combat piracy that Psygnosis endeavored to make the external parts of their games’ presentations as spectacular — and as appealing to teenage sensibilities — as the graphics in the games themselves. Most of their games were sold in bloated oblong boxes easily twice the size of the typical British game box — rather ironically so, given that few games had less need than those of Psygnosis for all that space; it wasn’t as if there was a burning need for lengthy manuals or detailed background information to accompany such simple, generic shoot-em-ups. Virtually all of Psygnosis’s covers during this era were painted by Roger Dean, the well-known pop artist with whom Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson had first established a relationship back in the Imagine days. “If you’re asking so much for a piece of software,” said Hetherington, “you can’t package it like a Brillo pad.”

Dean’s packaging artwork was certainly striking, if, like most things associated with Psygnosis during this period, a little one-note. Not a gamer himself, Dean had little real concept of the games he was assigned, for which he generally drew the cover art well before they had been completed anyway. He usually had little more to go on than the name of the game and whatever said name might happen to suggest to his own subconscious. The results were predictable; the way that Psygnosis’s covers never seemed to have anything to do with the games inside the boxes became a running joke. No matter: they looked great in their own right, just begging to be hung up in a teenager’s bedroom. In that spirit, Psygnosis took to including the cover art in poster or tee-shirt form inside many of those cavernous boxes of theirs. Whatever else one could say about them, they knew their customers.

It’s difficult to exaggerate the role that image played in every aspect of Psygnosis’s business. Some of the people who wound up making games for them, who were almost universally in the same demographic group as those who played their games, were first drawn to this particular publisher by the box art. “I was always a fan of the art style and the packaging,” remembers outside developer Martin Edmondson. “Against a sea of brightly-colored and cheap-looking game boxes the Psygnosis products stood out a mile and had an air of mystery — and quality — about them.” Richard Browne, who became a project manager at Psygnosis in early 1991, noted that “while many of the games they produced were renowned somewhat for style over substance, they just oozed quality and the presentation was just sheer class.”

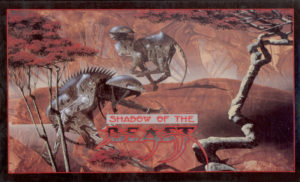

The quintessential Psygnosis game of the period between 1987 and 1990 is undoubtedly the 1989 release Shadow of the Beast. The company’s most massively hyped title since the days of Brataccas and the Imagine megagames, it differed from them by rewarding its hypers with sales to match. It was the creation of a three-man development studio who called themselves Reflections, who had already created an earlier hit for Psygnosis in the form of Ballistix. Unusually among Psygnosis’s outside developers, Reflections created all of their own graphics, outsourcing only the music and of course the Roger Dean cover art. Martin Edmondson, the leader of the Reflections trio, makes no bones about their priorities when creating Shadow of the Beast:

For me, it was about the technical challenge of getting something working that was far beyond the theoretical limits of the machine. It wasn’t a story originally. It was a technical demonstration of what the machine could do — I suppose sort of a “look how clever we are” type of thing. So, yeah… less interested in the subtleties of game design and game process, more “let’s see if we can do what these big expensive arcade machines are doing on our small home computer.”

Edmondson describes the book that most inspired Shadow of the Beast not as any work of fiction but rather the Amiga Technical Reference Manual. Every element of the game was crafted with the intention of pushing the hardware described therein to heights that had only been hinted at even in Psygnosis’s own earlier works. Barely two years after Shadow of the Beast‘s release, Edmondson’s assessment of its design — or perhaps lack thereof — was unflinching: “We couldn’t get away with it now. It was definitely a case of being in the right place at the right time. Apart from how many colors and layers of parallax and monsters we could squeeze on screen, no thought went into it whatsoever.” Its general approach is similar to that of the earlier Barbarian, but it’s a much more constrained experience than even that game had been. As the landscape scrolls behind your running avatar, you have to execute a series of rote moves with pinpoint timing to avoid seeing him killed. It’s brutally difficult, and difficult in ways that really aren’t much fun at all.

But, as Edmondson himself stated, to complain overmuch about the gameplay of Shadow of the Beast is to rather miss the point of the game. While plenty of praise would be given to the atmospheric soundtrack Psygnosis commissioned from veteran game composer David Whittaker and to the unprecedentedly huge sprites programmed by Reflections, the most attention of all would be paid to the thirteen layers of parallax scrolling that accompany much of the action.

Parallax scrolling is a fancy phrase used to describe the simulation of a real-world property so ingrained in us that we rarely even realize it exists — until, that is, we see a videogame that doesn’t implement it. Imagine you’re standing at the edge of a busy highway on a flat plain, with a second highway also in view beyond this one, perhaps half a kilometer in the distance. Cars on the highway immediately before you whiz by very quickly, perhaps almost too quickly to track with the eyes. Those on the distant highway, however, appear to move through your field of view relatively slowly, even though they’re traveling at roughly the same absolute speed as those closer to you. This difference is known as the parallax effect.

Because the real world we live in is an analog one, the parallax effect here has infinite degrees of subtle shading. But videogames which implemented parallax in the 1980s usually did so on only one or two rigid levels, resulting in scrolling landscapes that, while they may have looked better than those showing no parallax effect at all, nevertheless had their own artificial quality. Shadow of the Beast, however, uses its thirteen separate parallax layers to approach the realm of the analog, producing an effect that feels startlingly real in contrast to any of its peers. As you watch YouTube creator Phoenix Risen’s playthrough of some of the trained version of Shadow of the Beast below — playing a non-trained version of this game is an exercise for masochists only — be sure to take note of the scrolling effects; stunning though they were in their day, they’re like much else that used to impress in vintage Psygnosis games in that they’re all too easy to overlook entirely today.

Whether such inside baseball as the numbers of layers of parallax scrolling really ought to be the bedrock of a game’s reputation is perhaps debatable, but such was the nature of the contemporary gaming beast upon which Shadow of the Beast so masterfully capitalized. Edmondson has admitted that implementing the thirteen-layer scheme consumed so much of the Amiga’s considerable power that there was very little left over to implement an interesting game even had he and his fellow developers been more motivated to do so.

Psygnosis sold this glorified tech demo for fully £35, moving into the territory Imagine had proposed to occupy with the megagames back in the day. This time, though, they had a formula for success at that extreme price point. “Shadow of the Beast just went to show that you don’t need quality gameplay to sell a piece of software,” wrote a snarky reviewer from the magazine The One. Zzap! described it only slightly more generously, as “very nice to look at, very tough to play, and very expensive.” Whatever its gameplay shortcomings, Shadow of the Beast became the most iconic Amiga game since Cinemaware’s Defender of the Crown, the ultimate argument to lay before your Atari ST-owning schoolmate. “Within a week or so of launch they could barely press enough disks to keep up with demand,” remembers Edmondson. For the Imagine veterans who had stayed the course at Psygnosis, it had to feel like the sweetest of vindications.

One can’t help but admire Psygnosis’s heretofore unimagined (ha!) ability to change. They had managed to execute a complete about-face, shedding the old Imagine legacy of incompetence and corruption. In addition to being pretty poor at making games people actually wanted to play, Imagine had been staggeringly, comprehensively bad at all of the most fundamental aspects of running a business, whilst also being, to put it as gently as possible, rather ethically challenged to boot. They had had little beyond audacity going for them. Few would have bet that Psygnosis, with two of their three leaders the very same individuals who had been responsible for the Imagine debacle, would have turned out any different. And yet, here they were.

It’s important to note that the transition from Imagine to Psygnosis encompassed much more than just hitting on a winning commercial formula. Ian Hetherington and Dave Lawson, with the aid of newcomer Jonathan Ellis, rather changed their whole approach to doing business, creating a sustainable company this time around that conducted itself with a measure of propriety and honesty. Whereas Imagine had enraged and betrayed everyone with whom they ever signed a contract, Psygnosis developed a reputation — whatever you thought of their actual games — as a solid partner, employer, and publisher. There would never be anything like the external scandals and internal backstabbing that had marked Imagine’s short, controversial life. Indeed, none of the many outside developers with whom Psygnosis did deals ever seemed to have a bad word to say about them. Hetherington’s new philosophy was to “back the talent, not the product.” Said talent was consistently supported, consistently treated fairly and even generously. Outside developers felt truly valued, and they reciprocated with fierce loyalty.

As people interested in the processes of history, we naturally want to understand to what we can attribute this transformation. Yet that question is ironically made more difficult to answer by another aspect of said transformation: rather than making a constant spectacle of themselves as had Imagine, Psygnosis became a low-key, tight-lipped organization when it came to their personalities and their internal politics, preferring to let their games, their advertising, and all those gorgeous Roger Dean cover paintings speak for them. Neither Hetherington, Lawson, nor Ellis spoke publicly on a frequent basis, and full-on interviews with them were virtually nonexistent in the popular or the trade press.

That said, we can hazard a few speculations about how this unlikely transformation came to be. The obvious new variable in the equation is Jonathan Ellis, a quietly competent businessman of exactly the type Imagine had always so conspicuously lacked; his steady hand at the wheel must have made a huge difference to the new company. If we’re feeling kind, we might also offer some praise to Ian Hetherington, who showed every sign of having learned from his earlier mistakes — a far less common human trait than one might wish it was — and having revamped his approach to match his hard-won wisdom.

If we’re feeling a little less kind, we might note that Dave Lawson’s influence at Psygnosis steadily waned after Brataccas was completed, with Hetherington and Ellis coming to the fore as the real leaders of the company. He left entirely in 1989, giving as his public reason his dissatisfaction with Psygnosis’s new focus on outside rather than in-house development. He went on to form a short-lived development studio of his own called Kinetica, who released just one unsuccessful game before disbanding. And after that, Dave Lawson left the industry for good, to join his old Imagine colleague Mark Butler in modern obscurity.

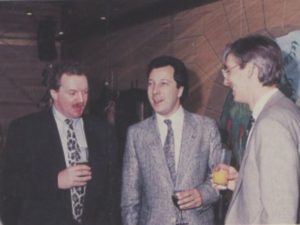

A rare shot of Ian Hetherington, left, with his business partner Jonathan Ellis, right, in 1991. (In the middle is Gary Bracey of Imagine’s old Commercial Breaks companion Ocean Software.) In contrast to the look-at-me! antics of the Imagine days, Hetherington and Ellis were always among the most elusive of games-industry executives, preferring to let the products — and their superb marketing department — speak for themselves.

None of this is to say that there were no traces of the Imagine that had been to be found in the Psygnosis that was by 1989. On the contrary: for all the changes Hetherington and Ellis wrought, the new Psygnosis still evinced much of the Imagine DNA. To see it, one needed look no further than the Roger Dean cover art, a direct legacy of Imagine’s megagame dream. Indeed, the general focus on hype and style was as pronounced as ever at Psygnosis, albeit executed in a far more sophisticated, ethical, and sustainable fashion. One might even say that Hetherington and Ellis built Psygnosis by discarding all the scandalous aspects of Imagine while retaining and building upon the visionary aspects. Sometimes the legacy could be subtle rather than obvious. For example, the foreign distribution network that had been set up by Bruce Everiss to fuel Imagine’s first rush of success was also a key part of the far more long-lived success enjoyed by Psygnosis. Hetherington and Ellis never forgot Everiss’s lesson that having better distribution than the competition — having more potential customers to sell to — could make all the difference. As home computers spread like wildfire across Western Europe during the latter half of the 1980s, Psygnosis games were there early and in quantity to reap the benefits. In 1989, Jonathan Ellis estimated that France and West Germany alone made up 60 percent of Psygnosis’s sales.

Psygnosis knew that many of their potential customers, particularly in less well-off countries, weren’t lucky enough to own Amigas. Thus, while Psygnosis games were almost always born on Amigas, they were ported widely thereafter. Like those of Cinemaware, Psygnosis games gained a cachet merely from being associated with the Amiga, the computer everyone recognized as the premiere game machine of the time — even if some were, for reasons of that afore-described platform patriotism, reluctant to acknowledge the fact out loud. Even the most audiovisually spectacular Psygnosis experiences, like Shadow of the Beast, were duly ported to the humble likes of the Commodore 64 and Sinclair Spectrum, where they paled in comparison to their Amiga antecedents but sold well anyway on the strength of the association. This determination to meet the mass market wherever it lived also smacked of Imagine — albeit, yet again, being far more competently executed.

In addition to cutting ties with Dave Lawson in 1989, Hetherington and Ellis also shed original investor and Liverpool big wheel Roger Talbot Smith that year, convincing him to give up his share of the company in return for royalty payments on all Psygnosis sales over the next several years. Yet, and even as their network of outside developers and contractors spread across Britain and beyond, Psygnosis’s roots remained firmly planted in Liverpudlian soil. They moved out of their dingy offices behind Smith’s steel foundry and into a stylish gentrified shipping warehouse known as the South Harrington Building. It lay just one dock over from the city’s new Beatles museum, a fact that must have delighted any old Imagine stalwarts still hanging about the place. While an American journalist visiting Psygnosis in early 1991 could still pronounce Liverpool as a whole to be “very grim,” they were certainly doing their bit to change the economic picture.

Meanwhile Ian Hetherington in particular was developing a vision for Psygnosis’s future — indeed, for the direction that games in general must go. Like many of his counterparts in the United States, he saw the CD-ROM train coming down the track early. “The technological jump is exponential,” he said, “which means you have to make the jump now — otherwise when CD happens you’re going to be ten years behind, not two, and you’re never going to catch up.” With the move to the larger South Harrington Building offices, he set up an in-house team to research CD-ROM applications and develop techniques that could be utilized when the time was right by Psygnosis’s collection of loyal outside developers.

In this interest in CD-ROM — still a rare preoccupation among British publishers, where consumer-computing technology lagged two or three years behind the United States — Psygnosis once again invited comparison with that most obvious point of comparison, the American publisher Cinemaware. Yet there were important differences between the two companies on this front as well. While Cinemaware invested millions into incorporating real-world video footage into their games, Hetherington rejected the fad of “interactive video” which was all the rage in the United States at the time. His point of view reads as particularly surprising given that so many interactive-video zealots of the immediate future would be accused of making pretty but empty games — exactly what Psygnosis was so often accused of in the here and now. It serves perhaps as further evidence of Hetherington’s ability to learn and to evolve. Hetherington:

Interactive video is a farce. It is ill-conceived and it doesn’t work. It is seductive, though. Trying to interact with £400,000 worth of video on disc is a complete fiasco. We are looking for alternative uses of CD. You have to throw your existing thinking in the bin, then go sit in the middle of a field and start again from scratch. Most developers will evolve into CD. They will go from 5 MB products to 10 MB products with studio-quality soundtracks, and that will be what characterizes CD products for the next few years.

Hetherington also differed from Cinemaware head Bob Jacob in making sure his push into CD-ROM was, in keeping with the new operational philosophy behind Psygnosis in general, a sustainable one. Rather than betting the farm like his American counterpart and losing his company when the technology didn’t mature as quickly as anticipated, Hetherington used the ongoing sales from Psygnosis’s existing premium, high-profit-margin games — for all their audiovisual slickness, these simple action games really didn’t cost all that much to make — to fund steady, ongoing work in figuring out what CD-ROM would be good for, via an in-house team known as the Advanced Technology Group. When the advanced technology was finally ready, Psygnosis would be ready as well. At risk of belaboring the point, I will just note one last time how far this steady, methodical, reasoned approach to gaming’s future was from the pie-in-the-sky dreaming of the Imagine megagames.

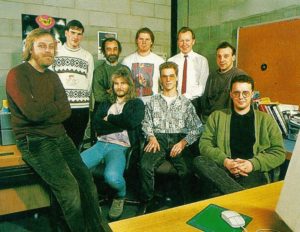

The Psygnosis Advanced Technology Group in 1991. Standing second from left in the back row is John Gibson — the media’s favorite “Granddad” himself — who after spending some years with Denton Designs wound up rejoining some other old Imagine mates at Psygnosis.

As the 1990s began, then, Psygnosis had a lot going for them, both in the Amiga-dominated present and in the anticipated CD-ROM-dominated future. One thing they still lacked, though — one thing that Imagine also had resoundingly failed to produce — was a single game to their name that could be unequivocally called a classic. It was perhaps inevitable that one of the company’s stable of outside developers, nurtured and supported as they were, must eventually break away from the established Psygnosis gameplay formulas and deliver said classic. Still, such things are always a surprise when they happen. And certainly when Psygnosis did finally get their classic, the magnitude of its success would come as a shock even to them.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Rebecca Levene and Magnus Anderson; the extra interviews that accompanied the documentary film From Bedrooms to Billions; Retro Gamer 50; Computer and Video Games of October 1987; STart of June 1990; The One of July 1989, March 1990, September 1990 and February 1992; The Game Machine of October 1989 and August 1990; Transactor of August 1989; Next Generation of November 1995; the online articles “From Lemmings to Wipeout: How Ian Hetherington Incubated Gaming Success” from Polygon, “The Psygnosis Story: John White, Director of Software” from Edge Online, and “An Ode to the Owl: The Inside Story of Psygnosis” from Push Square.)