The first sign that something might be seriously wrong at Imagine Software greeted game buyers in March of 1984, when the company unexpectedly started slashing prices. They announced that their games would go from the current £5.50 to just £3.95, cheaper than all but the cheapest budget titles currently on store shelves. In doing so, they ignited more than a little consternation in their industry.

Like most industries, that of computer games operated within a framework of tacit agreements about how business should be conducted, and some of the most sacred of these had to do with pricing. Games were arrayed in tiers, with standard full-price titles of the sort sold by Imagine expected to be priced at over £5. From the industry’s standpoint, the danger of going lower was bound up in the stark business reality that prices are always easier to cut than they are to raise again. If one publisher chose to cut their prices below the £5 threshold, they could then force the rest of them to do likewise in order to compete, igniting a dangerous price war that would almost certainly end with the new average prices for games considerably lower than they had been before. And the end result of that situation, most believed, would be lower profits for everyone. Imagine, with their penchant for combining mediocre games with extravagant claims of success, had never been terribly well-liked among their peers. This latest move, it seems safe to say, did nothing to improve their popularity.

But the move made them most unpopular of all with the shopkeepers who sold their games, the very people Bruce Everiss had worked so assiduously and successfully to cultivate the previous year. The Imagine games already on their shelves had been purchased at a wholesale price which assumed they would sell at retail for £5.50, yet the shops would now be expected to price them at just £3.95 — a money-losing proposition. Imagine had done nothing to address this situation; certainly there had been no talk of compensating the shopkeepers. They were, it seemed, expected to eat their losses with a smile and say thank you.

Of course, the deeper question about the price cuts wasn’t the what or even the how of the thing but the why of it. When asked why Imagine was making this move now, Bruce Everiss trotted out a couple of different answers. One was that the games Imagine would be releasing later in the year would be so spectacular that they would render everything that had come before them obsolete; thus the price cuts were a way of clearing out the old to make way for the new. But Everiss also alluded to software piracy, the industry’s ever-present bugaboo, expressing a hope that a lower price would make customers more likely to buy Imagine’s games than to copy them from their mates. This response struck many as the more honest answer, and pointed clearly to a company whose sales weren’t quite as healthy as they claimed them to be.

Indeed, Imagine was focusing more and more on the real or theoretical effects of piracy, throwing around heaps of eye-opening but unsubstantiated figures on the subject, such as the claim that only one out of eight people who played the average Imagine game had actually bought it. To this day, Everiss blames a sudden onslaught of piracy for a collapse in sales, but, given that Imagine’s peers experienced nothing like the same collapse, it stands to reason that there was at the very least a lot more to the story than that age-old software-industry bogeyman. The fact was that whatever cachet the Imagine name still held among ordinary gamers was fast draining away in the face of so many underwhelming releases. When a magazine ran a poll to determine the top-ten worst games for the Sinclair Spectrum, three of Imagine’s made the list. This was one chart Imagine would have preferred not to top.

The questions surrounding Imagine only multiplied when, just two weeks after cutting their prices, they suddenly raised them back to the original £5.50. Pressed again for a reason, Everiss claimed they had listened to the discontent of their peers. “We knew that dropping the price would increase sales, but what we hadn’t bargained for was the industry reaction, which was universally unfavorable, from both the distributors and other software houses,” he said. “The feeling was that if we did do it, it would upset the marketplace to such a degree that it would put many smaller software houses out of business.” Such concern about the fates of other software houses had never been a notable aspect of the Imagine character before, and rang more than a little false now. Far from protecting their competition, Imagine looked more and more like a company searching for a way to save themselves. When the rest of the industry looked at Imagine now, they saw a company with shrinking sales who had tried to remedy the situation by slashing their prices, found it only made their bottom line worse, and hastily reversed course. Once so eminently self-assured, Imagine now seemed to lack the courage of their own convictions as they flailed about in search of the magic bullet that would fix their problems overnight. Some began to make jokes about what they called Imagine’s “nervous pitching,” invoking the name of one of their games: Schizoids.

Had they known the full story behind the pricing schizophrenia, Imagine’s competitors would have been able to enjoy their full measure of vindication along with a heaping dose of schadenfreude. Going into the 1983 Christmas season, which Bruce Everiss had ebulliently declared was going to be huge beyond belief, they’d hatched a plan to squeeze out other publishers by buying up literally the entire production capacity of one of the industry’s biggest cassette duplicators. After all, whatever games they manufactured but didn’t sell that Christmas they’d easily be able to move in 1984; Everiss claimed that year was bound to be twice the year for games that 1983 had been.

It all backfired horribly. Imagine sold far fewer games than they had expected to that Christmas, and then their sales dwindled to the merest trickle in the new year, leaving them with hundreds of thousands of aging games that had never been all that great in the first place piled up in warehouses. When thieves broke into one of the warehouses and left with an alleged £200,000 worth of Imagine cassettes, it came almost as a relief; at least they wouldn’t have to pay the storage bills for them anymore.

The full story of the backfired tape-duplication plot — about as clear-cut a case of karma being a bitch as you’ll find in the history of the games industry — wouldn’t surface for many months. But, try as Imagine might to hide them, other cracks in the facade were continuing to appear in the here and now. Late in 1983, they had signed a high-profile deal worth a purported £11 million with Marshall Cavendish, a major publishing consortium, to provide cassettes full of games and programming tutorials to accompany Input, a slick weekly computer magazine which their new partner was planning to launch in 1984. Imagine had purportedly hired many staffers just to work on the Input project. Yet in that same confounding March of 1984 the deal unexpectedly went away. Once again, Everiss spun like crazy:

The original concept was that these would be average, run-of-the-mill games. As we started developing the games, we put them out to be play-tested, which involves comparing them against the reviewer’s favorite game. So the games were enhanced and so on, so that in the end they became so good that it wasn’t worth our while putting them out through Marshall Cavendish.

Everiss’s claim that Imagine’s games were just too good for the magazine was belied by the rumor that it was Marshall Cavendish who had nixed the deal, after Imagine persisted in missing deadlines and delivering substandard work.

Other unsavory stories swirled around Imagine and the Guild of Software Houses, an industry advocacy organization similar to the Software Publishers Association in the United States. GOSH, it seemed, had inexplicably rejected Imagine’s bid for membership. Everiss claimed it was because Imagine was “too big” for what he described as a “small, mutual-back-slapping organization really.” Still, size hadn’t prevented the likes of Thorn EMI from being accepted by the Guild. Did GOSH know something about Imagine that most people didn’t?

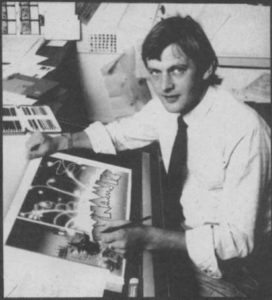

Commercial artist Stephen Blower, one of the many whose dealings with Imagine left him feeling bitter and betrayed, at work on one his trademark pieces of slick, airbrushed-looking art.

Still other past events were cast in a different light by these developments. Just after Christmas, Stephen Blower’s Studio Sing, the advertising agency formed to manage Imagine’s public relations, had suddenly gone bankrupt, leaving behind some £90,000 worth of Christmas advertising bills that were still unpaid to them by Imagine and that thus also now went unpaid to the magazines which had run the spots. A healthy and ethical Imagine, it seemed to the magazines who were being stiffed, might have made the payments directly to them. But they did no such thing.

Word on the street in Liverpool had it that Imagine’s managers had contrived to starve Studio Sing in an attempt to force Blower to relinquish his 10-percent stake in their company, only to find that Blower preferred to let his agency die rather than give in to the bullying. It all sounded plausible enough — but maybe the real reason Studio Sing had been starved, murmured a few, was far simpler: maybe Imagine just hadn’t had the £90,000 to pay out in the first place, and had engineered the agency’s failure as a way to dodge their debts. Whatever the reasons behind what transpired, an embittered Blower was left holding the bag:

Imagine tried to accuse me of certain things that I didn’t do. For instance, they said I was detrimental to the company’s image and that I was booking advertising that wasn’t wanted. I was accused of stealing, or misappropriating, £10,000, and my wife was accused of being incapable of keeping the books at Studio Sing.

They were obviously after my 10 [percent]. Imagine owed Studio Sing £89,000, so the way I see it is they attempted to brush that debt under the carpet. The allegations were just an attempt to condone their actions. I was probably the only one at Imagine who stuck to what he was best at doing.

With the stubborn Blower refusing to exit the scene, Imagine now had a shareholder at open war with his colleagues — although Blower, owning just 10 percent of the company, couldn’t do much to affect its direction. He would soon have cause to wish he had given up his stake when asked and gotten out of Dodge while the getting was good.

Behind their public image of cheeky Scousers who had made it big, Imagine was developing a reputation as a very nasty place, replete with fractious infighting and rampant paranoia. When Alan Maton, a Bug-Byte veteran who worked briefly for Imagine as well, left to start a software developer of his own, Dave Lawson allegedly subjected him to such a campaign of invective and harassment that he was forced to seek the protection of a restraining order. After Colin Stokes, a sales manager for Imagine, left to join Maton’s new company, he claimed that Lawson and Mark Butler had bugged his phone upon classing him as an “unreliable,” then thrown into his shocked face verbatim transcripts of his betrayal in place of a conventional exit interview; he was forced to run for the door amidst a hail of insults and legal threats. Incredibly, the one and only issue of Imagine’s fan newsletter — another initiative that was launched with great hoopla and then abandoned as too much trouble to be worth continuing — published samples from the telephone transcripts, claiming that there were 60 more pages of same where these had come from, a petty and potentially actionable public airing of dirty laundry.

Legal threats were becoming something of a way of life for Imagine. When Your Computer magazine — who, perhaps not incidentally, had been among those hounding Imagine for unpaid advertising bills — printed a listing for a game that Bruce Everiss judged to be too similar to one of Imagine’s, the latter whispered darkly that he had his solicitors “looking into the matter.”

Rumors spread that the company as a whole had been split into two camps, with Everiss and Butler leading one faction and Lawson and the recently hired Ian Hetherington, Imagine’s financial director and emerging fourth principal power, leading the other; this split accounted for much of the mixed messaging on things like a pricing strategy. When a journalist from Crash magazine spent a day at Imagine for a profile piece, Lawson and Hetherington never showed up for work at all and Butler only popped in for a few minutes, leaving their would-be interviewer to spend most of the day in the company of Everiss. When the final piece appeared, filled for understandable reasons mostly with Bruce Everiss quotes, the journalist got an irate phone call from a jealous Mark Butler, asking why his article had made it sound like Everiss ran the whole company.

Through it all, Imagine’s hype machine was still cranked up and spewing. Hype was, after all, the one thing Imagine had always done best. Almost drowning out all of the other mixed signals in the press was a new campaign for what Imagine liked to call “megagames.” These were nothing less than the amazing new things that Imagine had, according to one of Everiss’s accounts anyway, slashed prices to make room for. They now took center stage in Imagine’s advertising, a publicity blitz for as-yet nonexistent games the like of which the industry had never seen. The magazines, not wanting to be left out in the cold if the megagames did indeed blow up huge, accepted these latest advertisements even after having been stiffed the last time around.

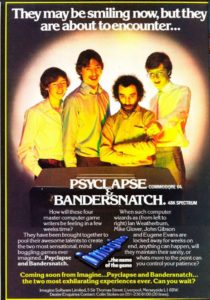

Imagine started running advertisements like this for their upcoming “megagames” very early in 1984. Featured from left to right are programmers Ian Weatherburn, Mike Glover, John Gibson, and Eugene Evans.

It was very hard to determine from the advertisements, or even from talking to Imagine directly, exactly what a megagame would be. Everiss claimed they would be packaged far more elaborately than was the norm in Britain at the time, more in keeping with the games companies like Infocom and Origin were selling in the United States. (He was keenly aware of the state of games across the Atlantic, having been a regular visitor to American trade shows since the late 1970s.) Yet improved packaging was by no means the sum total of the megagame proposition. More intriguing was the prospect of some sort of machine-enhancing hardware add-on that would be included in the box. “We’ve gone as far as we can on these machines given their hardware capabilities, and we have come up with a way of increasing the power of the machine,” said Everiss. “It is not done through software.” Imagine’s games were hardly noted for pushing the capabilities of existing machines all that hard; games coming from competing houses regularly gave the lie to Imagine’s claim of having gone “as far as we can” with current hardware. Nevertheless, this hybrid software/hardware approach was certainly intriguing.

And yet the question remained: what would the megagames be like to actually play? Imagine was frustratingly vague, leaving one with the impression that they were either incredibly cagey or that they themselves didn’t quite know what they were making. All they ever clearly said was that the megagames would be great. Bruce Everiss:

The thing about it is that the game is so big and complex and involved — and it contains several new areas, things that have never been done before. We aren’t going to release it until it’s perfect. The only analogy we can use without giving the game away is that it’s going to make anything that’s gone before look like Noughts and Crosses.

No one’s even seen them yet! They’re so secret that most people at Imagine know nothing about them. Even the people who are working on the project only know sufficient to do their own piece of the work. We give them information on a “need to know” basis. What we’re worried about is somebody else finding out what we’re doing and emulating it.

You don’t have a score, you don’t have levels, you’ve gone completely beyond all that. You wait and see. You’ll be phoning me up when you get them, saying “Brucie was right!”

The price Imagine planned to charge for all this awesomeness just kept going up. Starting at £15, it rose to £20, then to £30, then to £40 — almost eight times the price of the typical new game. “It’s got to be something extraordinary to sell for that price,” said one skeptical distributor. “We’ll just have to wait and see.” “Imagine are claiming these programs are completely innovative,” said another. “If that’s the case, it’s marvelous and good for the industry.” The problem, of course, was that very big “if” which began his thought. Once you cut through all the hype, Imagine’s track record at making innovative games wasn’t very good. Undaunted, they said that the first megagame, to be called Bandersnatch, would be out that summer, and that the next, Psyclapse, would ship well before Christmas.

Many years later, Bruce Everiss would admit to much of the real thinking behind Imagine’s drive to include hardware with their games: “The megagames were an attempt to make our games copy-proof by incorporating a ‘dongle’ that plugged into the back of every customer’s computer.” Only afterward did Imagine’s programmers hatch a scheme to build 64 K of ROM memory into the dongles to supplement the 48 K of RAM in the Sinclair Spectrum, allowing them, theoretically at least, to make games that were much bigger than the norm. Unfortunately, the company, not being home to any hardware engineers, was very ill-equipped to see such a scheme through.

Then, in the midst of all this swirling chaos, the BBC arrived on the scene.

Commercial Breaks director Paul Anderson had first taken note of the emerging computer-game industry very early in 1984, judging it to be a natural subject for an episode of a television series about British entrepreneurs and emerging markets. Flipping through the computer magazines, he saw that one company had the slickest, most elaborate, and most extensive advertising campaign of any of them: Imagine Software. It didn’t take long to connect Imagine with the minor media celebrity Eugene Evans, whose story Anderson, like just about everyone else who had picked up a newspaper during the previous year, had already read. Choosing Imagine as one of his two case studies — the other would be Manchester’s Ocean Software — he made the trip to Liverpool to discuss the idea in person with Butler, Lawson, Everiss, and Hetherington. He didn’t anticipate a lot of problems getting them to agree. Anyone who knew anything about Imagine knew that they loved publicity, and the publicity possibilities for a British computer-game publisher in 1984 didn’t come much bigger than a starring role in a BBC television program. Much to Anderson’s surprise, though, the foursome proved initially reluctant to commit themselves. They had, as we’ve already seen, plenty of reasons not to want to allow any outsider unfettered access to all that was going on internally. It was Dave Lawson who finally turned the tide in Anderson’s favor. Whatever concerns his colleagues might have, he couldn’t resist the lure of having Imagine strut their stuff as Liverpool’s next Beatles on such a grand stage as this. This opportunity, he said, was just too huge to turn away.

When he showed up with his film crew some weeks later, Anderson’s director’s eye was first struck by what a great shooting location Imagine’s spacious accommodations were. The bustling warren of offices and cubicles smacked more of a well-heeled stockbroker than a small 18-month-old technology company. The BBC crew took the requisite time to gawk at and to shoot video of the Ferraris and BMWs that filled the parking garage alongside the star of the vehicular show, Mark Butler’s hand-built Harris racing motorcycle. Butler, Anderson learned, had formed a motorcycle-racing team along with some other like-minded Imagine people. The film crew dutifully followed them out to the Isle of Man for the TT Race, where Butler promptly crashed his bike attempting a reckless maneuver and was carried off to the hospital.

In the beginning, Anderson had no reason nor any desire to be skeptical of the success his subjects claimed to be enjoying. Not being all that plugged-in to the home-computer scene, he knew nothing of the rumors about Imagine. And anyway, the whole point of the program he worked for was to tell positive stories of modern British entrepreneurship, not to scandal-monger. Yet it didn’t take him long to pick up the feeling that, despite all the outward trappings of a booming company that surrounded him, something here didn’t quite add up.

His suspicions were first aroused by Eugene Evans, Imagine’s alleged wunderkind programmer. In an episode whose associations must have thrilled the Beatles-obsessed Dave Lawson — and that, indeed, may have been planted in the press by him or Everiss — Evans had been in the news recently for supposedly leaving the Imagine band to make a go of it as a solo artist, only to be lured back into the fold by the entreaties of his mates; shades of George Harrison walking out on the Beatles for a few days back in 1969. Asked whether the rumors about his brief departure were true, Evans, still playing his role superbly, had said in his best cheeky Beatle fashion, “I may have done. There again, I may just have gone on holiday.”

Anderson was naturally eager to spend time with Evans, whereupon he immediately noted the discrepancy between the teenager’s hype and his reality. His treatment around the office hardly fit the profile of Imagine’s star coder; in reality, he didn’t seem to be regarded by the other programmers as all that important at all. And, the leased Lotus in his driveway notwithstanding, he didn’t seem to live like a young man who was earning thousands of pounds every month.

Imagine’s official line had it that Psyclapse, the second of the megagames, was essentially Evans’s project. Perhaps Anderson shouldn’t have been surprised, then, that not much of anything seemed to be happening on that front. John Gibson, Imagine’s other star programmer, did seem to be working hard on Bandersnatch, but few others seemed to share his dedication. In fact, very few of the technical and support staff seemed to be working all that hard on anything at all. Management, meanwhile, was most focused, predictably enough, on all the PR trappings that would surround the megagames. Sitting in on meetings, Anderson learned of a scheme to have Imagine and their megagames commemorated forever via two marble slabs that would be laid in London’s Hyde Park; one couldn’t help but wonder what opinion the authorities who ran the park, whom Imagine had apparently not yet gotten around to contacting, might have thought of the plan to immortalize Imagine Software alongside the likes of the Duke of Wellington. Anderson heard far more discussion about what the megagame boxes should look like than he did about the actual games the boxes were to contain. Imagine had managed to contract with Roger Dean, an artist quite famous in certain circles for the surrealistic album covers he painted for Yes and other progressive-rock bands, to do the box art for the megagames. They were thrilled to have him, as they were thrilled with any public connection they could foster between their company and rock music. Still, there was considerable grumbling that Dean had demanded his £6000 fee be paid up-front. Anderson, by now thoroughly suspicious of his bright young sparks, remembers thinking that Dean was a very wise chap.

Imagine, Anderson was gradually coming to realize, was living on a diet of denial and wishful thinking. Already on April 16, 1984, before the BBC had even started filming, Cornhill Publications had submitted a petition at court to have Imagine forced into bankruptcy if they continued to leave unpaid a massive advertising bill. That June, just a few days before the BBC followed Butler out to the Isle of Man to watch him living his fantasy of the daredevil playboy, Imagine had been in court to argue against the petition, with scant evidence to hand to support their claim that this was just a bump in the road and they would soon be a viable business again — if, indeed, they had ever been a viable business in the first place. Shortly thereafter, Butler, Lawson, and Hetherington all disappeared entirely. The first of these had an excuse, being in recuperation after his motorcycle crash; rumors swirled that the latter two had actually fled the country to dodge the fallout from Imagine’s imminent demise. Only Everiss was left, still coming into the office every day out of some sense of duty.

By this point, those who remained were spending their working days watching videos, playing games, and generally goofing off, apparently determined to enjoy their brief taste of the good life as much as they could before the inevitable. Anderson would later compare these last days of life at Imagine to the desperate decadence of the final days inside Hitler’s bunker as the Soviet tanks closed in on Berlin. When he was asked why no one ever seemed to be available to talk to the BBC cameras anymore, Everiss answered thus:

Well, there was a whole pile of people just playing games there, and they’re hiding from the camera. If you go round the corner here, by the exit, you’ll find there’s a big pile of fire extinguishers because there’s been fire-extinguisher fights all week. That’s been the main event.

The only outsiders still knocking at the door all seemed to be trying to get someone to pay them the money they were owed. Anderson’s film crew captured a man from the cassette-duplication plant whose capacity Imagine had bought up the previous Christmas wandering forlornly about the premises, trying to get someone — anyone — to at least talk to him about the £60,000 his company was still owed. Trying to put a stop to the stream of dark-suited, grim-faced men who lined up to knock at their door each day, Imagine sent out a letter to all their creditors claiming they expected a windfall of £250,000 from some unspecified source within three weeks. The creditors, naturally, didn’t believe them, and the grim-faced men just kept coming, asking fruitlessly for face time with someone — with anyone.

The creditors had still more cause for alarm when it was announced that Beau Jolly, a publisher of discount game compilations, had bought the entire extant Imagine games catalog. This may have been the windfall Imagine had vaguely referred to in their letter to their creditors, although it seems doubtful that Beau Jolly paid them anywhere near £250,000 for their collection of aging, unimpressive games. The transaction prompted alarm rather than hope in the hearts of Imagine’s creditors because the games were assets that in the event of what now seemed the certainty of an Imagine bankruptcy could be sold off to reimburse said creditors. It all rather smacked of a management team trying to get what they could out of the company for themselves while they still had the chance, especially as no offers came forth to pay any of their bills in the aftermath of the sale. In what had long since become a typical scenario for anyone who got into bed with Imagine for any reason whatsoever, even the catalog’s purchaser was soon left feeling disappointed and betrayed. Colin Ashby, Beau Jolly’s managing director:

To be honest, I’m not very happy with the deal. We’re still waiting for the master tape of PC Bill, and I’m not convinced we’ve got everything we agreed to. We weren’t paying over money just for old stock. The idea was to invest in the new games as well, but I think something’s gone wrong. I’ve been trying to get Lawson, Butler, or Hetherington for weeks because we thought we were doing the new games as well in this deal. But I can’t get hold of them.

It really did seem like everyone who was ever foolish enough to make a deal with Imagine wound up in a plaintive state like this one. When someone mentioned to Ashby that the shareholders’ real motivation for selling off the catalog may have been to get money out of the company while they had the chance, it all suddenly made more sense to him: “What a revelation! I hadn’t thought of that.”

Despite his prominence, Bruce Everiss owned no stock in Imagine, and thus was somewhat insulated from the slow-motion car crash happening around him. With his colleagues having abandoned him to the creditors and the BBC, he was increasingly willing to dish the dirt, even as he endeavored to distance himself from what was now looking more like a full-on financial scandal than just another failed company. He made the incredible claim that Imagine had never paid any tax whatsoever on their earnings — indeed, had never even filed a tax return. That was supposed to be the department of financial director Ian Hetherington, but the latter had always been — perhaps, it now seemed, for good reason — the most inaccessible of all the principals to Anderson. And now, like Butler and Lawson, Hetherington had simply disappeared. Everiss declared all three of them “cowards.” “It makes me sick,” he said, “to think that the people who have worked so hard to make the wealth of Imagine have been left high and dry while the directors of the company have stripped it bare and got away scot-free. They did everything to line their own pockets.”

Everiss was plainly protesting a bit too much, given that he too hadn’t hesitated to drive a Ferrari on Imagine’s dime, and given that the “wealth” of Imagine had never really existed in the first place. The story of Imagine Software wasn’t that of a company that was hugely successful and then collapsed so much as it was that of a company that had been built on smoke and mirrors — verging on outright fraud if not crossing that line — from the very beginning. Still, at least Everiss was here, facing the music after a fashion — not to mention those ever-present fish-eye lenses of the BBC. Or he was for a while anyway: on June 29, he quit. With him left the last semblance of Imagine Software as a functioning company. Those who remained behind did so only because it was more fun to hang out here than it was at home.

On July 9, 1984, Imagine was forcibly dissolved by order of the court; the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back was a relatively modest advertising bill for £10,000 to VNU Business Publications, publisher of a short-lived magazine called Personal Computer Games. The long list of other unpaid creditors included Kilsdale, the Gloucestershire cassette duplicator whose capacity Imagine had bought up the previous Christmas; Marshall Cavendish, who were still waiting to be paid back some £250,000 they had given Imagine at the beginning of the cancelled magazine deal; the Liverpool City Council; Henry Matthews and Son, a printer; United Arab Shipping, who owned Imagine’s posh downtown office space; Scalchards, the wine merchant who had catered Imagine’s lavish private parties; G.D. Studios, the agency that had created Imagine’s advertising after Studio Sing had died or been killed; and most of the Spectrum magazines, all clamoring for payment for said advertising. Some of these last, most notably the widely beloved Crash magazine, would later claim that the money they didn’t receive from Imagine very nearly forced them to go under as well. In all, Imagine owed more than £500,000 to the aforementioned entities. When unpaid bank loans, back taxes, and other outstanding government obligations were eventually added to the total, it would reach more than £1 million. Those of you needing help putting these figures in perspective might wish to consider that a typical Liverpool dockworker at the time might earn a salary of about £4000 per year.

Mark Butler, right, with another of Imagine’s racers on the Isle of Man. This picture was taken just before he smashed up his bike and wound up in the hospital, giving him an excuse to avoid being present for much of the final phase of Imagine Software.

Still swaddled in bandages from his motorcycle escapade of a month earlier, Mark Butler chose the day of the bankruptcy order to return to Imagine’s offices. That same day, when the remaining handful of employees and the BBC film crew had all nipped off to the pub for lunch, the bailiffs showed up. When the Imagine people tried to reenter the premises, they found the door locked to them, and Anderson hastily signaled his crew to start rolling video. The offices and everything inside them, they were all informed by the bailiffs, were being forcibly repossessed right now for the benefit of Imagine’s many creditors; Anderson had considerable trouble convincing the bailiffs to let him come inside and extricate the rest of his film crew’s equipment from the jumble. The bailiffs also took that most conspicuous of all signs of Imagine’s alleged success: all of their fancy cars. According to Anderson’s recollection, Butler seemed more stunned and dismayed by the loss of his BMW than by anything else that was transpiring. He stood in a daze in the midst of it all, seeming for all the world like he genuinely had no idea how the situation had reached such an impasse.

Which isn’t to say that the rest of the Imagine crew reacted all that much more cogently. If the enduring image of the company’s brief heyday would always be that parking garage full of exotic cars, that of the collapse would be a few dozen confused young men milling around outside a door that had just been locked in their faces, trying to figure out what was happening and what they should do about it — all of it as captured by Paul Anderson’s remorseless cameras. He hadn’t known quite what he might be getting into in making his documentary about the British computer-game industry, but he had certainly never dreamed it would turn out like this. But then, it seems safe to say that those who still worked for Imagine felt much the same way.

Facing a court order, Lawson and Hetherington resurfaced at last for the final winding-up meetings, huddling together in a small room while creditors lined up in the hall outside to state their grievances and request financial redress. In the end, the court managed to recover about £300,000 for them by selling Imagine’s office furniture, computers, and all those exotic cars. Meanwhile the accusations continued to fly among the Imagine principals. Stephen Blower, the one-time head of Studio Sing, filed a criminal complaint against Butler and Lawson for ignoring a court order, issued back in February as a result of the fallout from his agency’s bankruptcy, to remove his name from a £100,000 bank guarantee. Asked directly about the matter, a police spokesman replied in terms that weren’t entirely reassuring if you were Butler or Lawson: “The Commercial Squad does not have warrants of arrest out for any of the directors. It is, however, looking at the case in a wider sense.” Butler and Lawson were eventually found guilty of being in contempt of court, but the judge ruled that he wouldn’t send them to prison or fine them if they would now remove Blower’s name as previously agreed and pay his legal fees. This latter they presumably finagled a way to do, as the matter then disappeared from the press.

As the fallout from Imagine’s messy end continued, Paul Anderson had retired back to London to put his documentary together. The finished product, which first aired on BBC2 on December 13, 1984, is as fascinating as it is frustrating. This being an era well before video became ubiquitous, we have precious few similar glimpses into the vintage British games industry. The documentary would thus be of interest even had it not involved such a storied crack-up as Imagine’s. Yet Anderson’s hands were tied to a large extent by the strictures of the Commercial Breaks series for which he had shot his video, with its 30-minute running time and its brief of presenting an essentially positive, upbeat take on modern British entrepreneurship. These factors dictated that he include barely ten minutes of the reported many hours of footage he had shot in and around Imagine; Ocean Software, a far less high-profile but also a far more successful operation, got the balance of the program’s running time. (The television critic for the Times of London hilariously described the two companies in Commercial Breaks as a contrast between “much skin cream, little aftershave” on the one side and “receding hairlines, spreading waists, grit of experience” on the other.) It’s likely that the rest of the Imagine footage, which would have been seen by the BBC’s management at the time as the leavings of a minor episode of a minor, ephemeral program, was destroyed long ago. So, we must content ourselves with what we have.

Few would shed any tears for Imagine Software. Competitors, creditors, and even more than a few ordinary gamers who had been burned by the mismatch between Imagine’s hype and their games’ reality rejoiced to see the company’s humiliating comeuppance on national television. As a final ironic note, Ocean Software, Imagine’s companion company in that episode of Commercial Breaks, wound up buying the name, which they judged to still have cachet in some Continental markets. In British gaming circles, however, the name of Imagine was destined to remain synonymous with hubris, greed, tomfoolery, and plain old dishonesty, and for very good reason.

In the wake of Imagine’s collapse, people were left to wonder how it could possibly be that this group of clueless, vindictive naifs could have enjoyed the trappings of success for as long as they had — could, for that matter, have ever enjoyed the trappings of success at all. Imagine’s story is one of those which come along every once in a while to illustrate how much of business — and, indeed, society — is ordered not so much by rigidly stipulated, explicit rules as intuitive, implicit norms of behavior. When a company like Imagine comes along, willing to violate all of those norms, it can take the people around them considerable time to catch on. Imagine’s name proved ironically appropriate: the entire company, the entire Imagine “boom,” was a supreme act of imagination on the part of those — and by no means does this group consist entirely or even mostly of those who actually worked at Imagine — who desperately wanted the dream to be true. Imagine told people they were successful, and people believed them, and so in a sense they did indeed become successful — for a time.

Anderson’s own final take on what he had witnessed over the course of his weeks in Liverpool was far less harsh than that of many others:

It was a fascinating time in a city at the focus of the software business. It’s a shame it all fell apart. There were a lot of talented people there who were let down. It’s a bit like a movie that never got made, all the technicians and all the energy, but the producers failed. It’s going to be interesting to see what will come of them all.

After such a spectacular fiasco as this one, you might expect the people who had made Imagine to hide themselves away in shame. But of course they weren’t that sort of people. On the contrary: most of the people who built Imagine and then burned it to the ground were destined to remain around the games industry for a long time to come. Only Mark Butler, something of an innocent soul at bottom, a fellow who had always seemed almost as over-matched as had been Eugene Evans for the role that was thrust upon him, went at all quietly into that good night, starting a non-gaming software business with his father.

Out of everyone involved with Imagine, it was Eugene Evans who seemed most doomed to fade back into obscurity. He had already entered the media’s “where are they now?” file by the beginning of 1985, when Your Computer reported that he had been forced to trade his famous Lotus for a second-hand Volkswagen Beetle; on the plus side, he could at least actually drive his latest car, having finally gotten a license. But Evans wound up surprising everybody. He went into the management side of the videogame business, a role for which he was far better-suited than that of programmer, and rose through the ranks to become a vice president at Electronic Arts, his brief period of celebrity as Britain’s Teenage Hacker Extraordinaire a mere footnote — an anecdote to share at parties — to a long and successful career.

Some of the other members of Imagine’s old programming staff, including John Gibson, went on to form a development studio of their own called Denton Designs. Without, as they put it, “people of the caliber of Bruce Everiss to cock it up for us,” they established a pretty good reputation, particularly as a maker of the British specialty that was action-adventures, surviving well into the 1990s.

For his part, the indefatigable Bruce Everiss wasn’t about to relinquish the spotlight, even if his choices in business ventures often remained problematic. He first reemerged as an enthusiastic spokesman for the Oric Atmos, an ill-fated attempt to challenge the likes of Sinclair, Acorn, and Commodore in the British home-computer market. After that effort went bust, he formed his own software company, Everiss Software, for just long enough to release a single mediocre game — the unfortunately named Wet Zone — for the BBC Micro. He then moved on to the new budget publisher Code Masters, whom he helped to create a new image for what used to be the dregs of the games industry, the titles on the £1.99 racks. But he remains most proud of having founded the All Formats Computer Fair, a series of events that ran for many years in Britain and helped to reconnect him to his roots as a tireless promoter of computing for the people — an aspect of his makeup that had, like so much else, rather gotten lost amidst all the hype of Imagine Software.

So, Bruce Everiss’s real achievements both before and after his involvement with Imagine are considerable. Yet even before the final collapse of Imagine he began engaging in an often-tortured exercise in triangulation with regard to what still remains for many — fairly or not — his most memorable legacy. He wishes to take credit for the new standards of presentation and advertising he installed at Imagine and for the distribution inroads he engineered, all of which had a major impact on the British games industry as a whole, while separating himself from the excess, waste, foolishness, and sheer incompetence that are an equally indelible part of the Imagine story. “Comparatively little was spent on advertising,” he stated in 1984 in an attempt to minimize his own culpability in Imagine’s legendary profligacy. One suspects that the many magazines who were stiffed for tens of thousands of pounds each by Imagine might beg to differ. (Then again, since Imagine for the most part never actually paid their advertising bills, maybe his claim is perversely true…)

Threading the needle of innovation and complicity at Imagine has led to changing messages over the years. In an opinion piece that took the form of a letter to Eugene Evans which he wrote for Your Computer in 1986, Everiss tried to disavow his role in sculpting the latter’s persona for public consumption, blaming it on his colleagues at Imagine in the abstract whilst indulging in a cruel and pointless critique of Evans’s coding skills while he was at it:

Imagine seized on you as a PR opportunity. The story of a working-class teenager earning a fortune in Liverpool was a natural for the mass media. You had a fleeting fame in newspapers and on television, with strong undertones of John Lennon involved. What you didn’t seem to realise is that Imagine didn’t do it as a favour for you, they did it for themselves. In fact, what they did for you was the exact opposite of a favour.

Back in reality, you wrote a simple game on the 3 K VIC called Wacky Waiters that was just tolerable. Catcha Snatcha which followed was unplayable. Frantic was so bad the company had to withdraw it. Then you converted to the Commodore 64 with an attempt to put Arcadia on it; it was a travesty.

The last few months at Imagine were wasted playing around while pretending to work on a game called Psyclapse. All these attempts at programming were on the relatively simple 6502. You never could handle the more complex Z80. The 68000 must seem as difficult as playing Rachmaninoff backwards on a mouth organ.

Yet, when interviewed for a 2012 book-length history of the British games industry, Everiss was back to being the proud Svengali, thrilled to take all the credit for his greatest personal marketing creation. He claimed that all of the aspects of the Eugene Evans persona that the media latched onto were consciously crafted by him and him alone to make them do just that. Tellingly, the only person who ever publicly compared Evans to John Lennon was Everiss himself. All these decades later, one does have to wonder why Everiss and his colleagues won’t simply admit that they were foolish lads who got carried away and made heaps of awful choices. Few would continue holding a grudge; given similar circumstances, I and plenty of you reading this today likely wouldn’t have done any better at their age.

But, again, neither Eugene Evans nor the rest of the deceptions Everiss indulged in with his colleagues at Imagine should be taken as the sum total of the man’s long career. Something that can easily get lost in an article like this one is the extent to which Everiss did succeed in turning humble Liverpool into one of Britain’s biggest hotbeds of game-development talent. Evans’s replacement in the popular press became Matthew Smith, a Liverpudlian programmer and Microdigital regular who had the advantage over his predecessor of being every bit as brilliant as his press notices would have him be. His games Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, the former published by Bug-Byte, were a sensation in Spectrum circles at the very time Imagine was imploding, and Smith himself became almost as big a mass-media celebrity as Evans had been. Imagine may have died, but Liverpool-based game development would live on.

As would the final two major players in the Imagine saga. For even as Imagine was burning down around them, and even as Everiss was already working to lay the blame elsewhere, Dave Lawson and Ian Hetherington were also working hard — working on a scheme to birth a phoenix out of the ashes.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Rebecca Levene and Magnus Anderson; Computer and Video Games of February 1984; Home Computing Weekly of March 20 1984, April 3 1984, December 4 1984, and February 13 1985; Personal Computer Games of March 1984, May 1984, June 1984, and July 1984; Your Spectrum of June 1984; Crash of August 1984, January 1985, and February 1985; Popular Computing Weekly of July 5 1984, July 19 1984, August 9 1984, October 4 1984, December 13 1984, and December 12 1985; Sinclair User of September 1984, October 1984, January 1985, and July 1985; CU Amiga of September 1992; Your Computer of November 1984, March 1985, and January 1986; Times of London of October 16 1984 and December 13 1984. See also Bruce Everiss’s “A History of the UK Video Game Industry Through My Eyes,” parts 1 and 2. The Commercial Breaks episode on Ocean and Imagine is available on YouTube.)