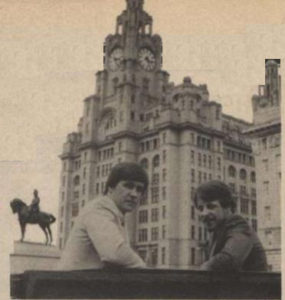

Once upon a time, the BBC played host to a half-hour current-affairs program called Commercial Breaks, which endeavored to document innovative businesses and emerging markets in Margaret Thatcher’s new, capitalist-friendly Britain. In April of 1984, Paul Anderson, one of the program’s stable of directors, began to shoot an episode about the computer-game industry, as seen through the eyes of Liverpool’s Imagine Software and Manchester’s Ocean Software. These two Northern software houses, each situated in a city that had been struggling mightily in recent years, had been specifically chosen to drive home the point that the craze for microcomputers and computer games was a national one rather than just a hobby of posh Londoners. Computers were transforming the way British youth from the Shetland Islands to Cornwall spent their free time, and computer games could earn those entrepreneurs who were successful at selling them millions of pounds. This, went the message from Thatcher on down, was an area where the new Britain stood poised to excel.

Whether by chance or design, the two publishers chosen for the program could hardly have been more different. Ocean was a quietly shipshape little operation, run by a balding fellow named David Ward who looked and talked more like an accountant than a brash entrepreneur. No matter: Imagine had brashness enough for both. The company’s absurdly young management and staff had been all over the tabloid media for months with their exotic sports cars, their extravagant claims about the money they were raking in, and an anti-establishment take on capitalistic excess worthy of rock stars.

Paul Anderson thought he was making a light documentary about an emerging business sector. But what he would end up with, at least for the part of the program devoted to Imagine, was something else entirely. Some fifteen years before Anderson started shooting his program, Michael Lindsay-Hogg had begun making a documentary about Liverpool’s four most famous sons as they went into the studio to record their latest album. Meant to show the Beatles’ triumphant return to playing together as a live band, the prelude to a major tour, Let It Be had instead wound up chronicling their demise for all the world to see. Now, sent to Liverpool to document the life of a vibrant young company, Paul Anderson would similarly wind up shooting its death, capturing for posterity on videotape the first notable instance of a game studio with a line of credit longer than their common sense imploding in spectacular fashion.

Yet what would follow said implosion would be in its way even more remarkable than all the excess and foolishness that had led Imagine to such an unhappy ending. For out of the ashes of Imagine Software would be born one of the most iconic British game makers of the latter 1980s and 1990s. Psygnosis, the direct heir to Imagine, would take an owl as their logo, but a better choice might have been a phoenix.

Back in 1961, one Brian Epstein had run a record store on Great Charlotte Street in downtown Liverpool, just blocks from where Imagine’s sprawling offices would be located 22 years later. Hearing his teenage customers talking more and more about a local beat group called the Beatles, Epstein finally made the ten-minute walk to the Cavern Club to hear them play a lunchtime concert one gray November day. Smitten immediately, he took on the role of the Beatles’ manager, bringing order to their chaos and transforming his four leather-clad proto-punks into the cheeky but lovable Fab Four that would go on to conquer the world.

For a few brief years thereafter, Liverpool had taken an unlikely place at the center of international pop culture, with Londoners suddenly trying to perfect Liverpool accents instead of the other way around, with teenagers from all over the world descending on the city en masse to see the place that had spawned their four youthful gods who still walked the earth. But the good times, alas, didn’t last for very long.

Liverpool had always been a rough-edged working-class city, but life there after the breakup of the Beatles in 1970 got harder for many of its inhabitants than anyone could remember. Britain as a whole had a very rough go of things during the 1970s, a decade marked by constant strikes, runaway inflation, and breakdowns of basic services like shipping, garbage collection, and power production. And as the country went, so went Liverpool, only with all the negative numbers multiplied by five or so. A moribund national economy meant a dramatic slowdown in the import and export of goods, any port city’s lifeblood. The advent of containerized shipping meant that thousands of dock-working jobs — relatively good-paying, unionized jobs — disappeared. Unemployment soared, and whole districts of the city filled up with dead-enders resigned to life on the dole, while huge swathes of the dockside area turned into a no man’s land of empty warehouses and rusting equipment, inhabited only by the homeless and the rising criminal class. Parts of Liverpool came to resemble a war zone.

In this environment, heaps of Liverpool youth still dreamed of using rock and roll as a means of escape, resulting in a local music scene that was as vibrant in the 1970s as it had been back in the 1960s — even if it no longer dominated the international charts like it once had. Yet music alone could hardly cure what ailed the city — not anymore, not this time. Liverpool’s next Brian Epstein would have to take a different tack.

In 1978, another young businessman opened a shop of his own very close to where Epstein’s NEMS record store had once stood. Trailing Silicon Valley’s famous Byte Shop by less than three years, Bruce Everiss’s Microdigital, located on Dale Street in the heart of Liverpool, was by some accounts the first specialized computer retailer anywhere in Britain. In the beginning, Everiss mostly sold the handful of build-it-yourself kit computers that were the only models available from British manufacturers; for the well-heeled, he imported a trickle of pre-assembled but expensive Commodore PETs from the United States. Much of his business was conducted via mail order, feeding the needs of hobbyist hackers all over the country.

Everiss was very aware of the problems plaguing his hometown, and had founded Microdigital with the intention of doing something about them. A committed backer of Margaret Thatcher from well before her ascent to prime minister in 1979 — in temperament and rhetoric he was a veritable prototype for Thatcher’s school of New British Entrepreneurs — his personality reflected a somewhat odd mixture of businessman and social crusader. For all of Liverpool’s well-documented problems, the city was also home to major electronics manufacturers like Plessey and Marconi, while the computer-science departments at institutes like Liverpool University and Liverpool Polytechnic were among the most respected in the country. Microdigital could be a bridge between the worlds of big business and academia and that of the street — the working-class heart of Liverpool.

Like so many of his fellow Liverpudlians, Everiss too took the legend of the Beatles to heart. Yet he did so in a more tangential fashion, seeing what had happened during the 1960s more as metaphor than blueprint. He believed the emerging computer industry could be to the Liverpool of the 1980s what music had been to the town of the 1960s. Seeing computers as a way off the dole for Liverpool youths with few other prospects, he made community outreach one of his shop’s most important missions, donating equipment to worthy causes like the computer courses that were run out of the Victoria Settlement, a local youth charity. Those same youth were always welcome in his shop, allowed to hang out there, learn a bit about programming, and play with computers they couldn’t possibly afford. An inveterate scenester, Everiss was fostering a real computer scene in Liverpool to go along with the city’s long-established musical tradition. And Ground Zero of this burgeoning computer scene, its version of the Cavern Club, was his little shop on Dale Street. The hangers-on there who showed the most potential could hope to become his employees.

Mark Butler was one of these lucky ones, an unusually personable “cheeky-chappy salesman type,” after Everiss’s description. He eventually became the shop’s day-to-day manager, freeing up his boss to focus on strategy.

One day in the summer of 1979, a curious 19-year-old named Dave Lawson wandered into the shop. Like non-musical Liverpool youths from time immemorial, he had gone to sea two years before, joining the merchant navy as the only other obvious escape from the workaday drudgery that was the lot of so many of his peers. But life at sea hadn’t agreed with him either, and he’d found himself back in his hometown and rather at loose ends: living with his parents, working odd jobs, and hitchhiking around Western Europe whenever his finances allowed. When he saw an advertisement for a Nascom kit computer in Electronics Today, it spoke to him for some reason he couldn’t entirely explain even to himself. Instead of hitting the road again with his meager savings, he carried it into Microdigital and walked out with his first computer. He took to it like a natural. He claimed it took him a week to learn machine language: “I didn’t bother with BASIC. I couldn’t see the point.” He became a regular at Microdigital, meeting Mark Butler there for the first time while playing a game of Star Raiders on one of the shop’s computers. “Good game,” said Butler. “I’m going to write one much better,” said Lawson. Everiss too was soon very aware of this new kid, who struck him as “very intense and very bright.”

Microdigital seemed successful enough on the surface, but, in what would be a common theme throughout Everiss’s business history, the shop never managed to make much if any money, doubtless thanks not least to all the extracurricular scene-building activities. Everiss sold it in July of 1980 to Laskys, an electronics chain with shops across Britain and Western Europe that had heretofore specialized in high-end stereo equipment; now, seeing a similar demographic of young men with money on their hands uniting the audiophile and computer-hobbyist markets, they were interested in branching out into computers as well. As part of the terms of sale, Everiss was required to stay on as a general manager for two and a half years. Over the course of that period, Laskys spread the Microdigital name across the country, first in the form of kiosks in existing Laskys shops, then as free-standing shopfronts of their own. A proud Scouser, Everiss was thrilled to be able to say that this expanding nationwide enterprise had its roots in humble Liverpool.

But Microdigital wasn’t the only enterprise that was growing as a direct result of Everiss’s efforts. Exactly one year after Laskys purchased Microdigital, a couple of Oxford University scions named Tony Baden and Tony Milner moved to Liverpool with their company Bug-Byte, the first British software publisher truly worthy of the name. They set up their new offices just around the corner from Everiss’s shop. Drawn to that location as much by Liverpool’s growing national reputation for being a well of self-taught programming talent as they were by the cheap rents, Bug-Byte grew to twelve employees within a year of their arrival. These had an average age of 19, and virtually all of them, along with many of the free-lance programmers whose games Bug-Byte churned out by the handful, were recruited from the floor of Everiss’s shop. Indeed, the two Tonys themselves fell under the sway of Everiss, who had big ideas about the future of consumer software, as he did about so many things. Just as the record collection of most music fans was worth far more than the stereo used to play it, he expected the software industry soon to dwarf the market for computer hardware.

Sometimes Everiss’s translations from the world of music to that of computer games could be almost literal. Taking the role of Bug-Byte’s marketing consultant, he convinced them to upgrade their packaging, fashioning full-color inlays for their cassette-based games that made them at a glance indistinguishable from a new pop album. The two Tonys came to sound like echoes of their marketing advisor, talking endlessly about “presentation” and “advertising” — and, one can’t help but notice, very little about the contents of the cassettes being presented and advertised.

Thankfully, Bug-Byte had recruited some very talented programmers from the Microdigital scenesters. The standout among them was none other than Dave Lawson, who established a reputation for being able to ingest whole the design of a new computer — of which there were many coming down the pipe in those days — and expel a playable game for it in a staggeringly short period of time. When the Commodore VIC-20 reached British shores in late 1981, he was there with a Pac-Man clone called VIC Men, the first third-party game to be published for the machine in Britain. (That game, alas, had to be pulled off the market when Bug-Byte received threatening legal notices from Atari, the holder of the rights to Pac-Man on home computers.) When the BBC Micro started shipping in early 1982, Lawson was there with a simplification of the old mainframe classic Star Trek which he called Space Warp, the first third-party game for that platform. And when the Sinclair Spectrum, the machine destined to become the heart of the British mass market for computer games, appeared shortly thereafter, Lawson made plans to welcome its arrival with a Space Invaders clone called Spectral Invaders. After the first thirteen Spectrums which Sinclair shipped to Bug-Byte all proved dead on arrival — quality control was not one of Sinclair’s strengths — a frustrated Lawson sat down with the machine’s technical manual and wrote his game’s code out by hand. He then typed it in when he finally got a functioning Spectrum, finding that it worked with only minimal alterations. Of such feats are coding legends made. Shortly thereafter, he produced one of the Speccy’s biggest early hits: Spectres, a witty twist on Pac-Man in which an electrician has to lay down light bulbs in the maze instead of eating dots therefrom in order to banish those pesky ghosts.

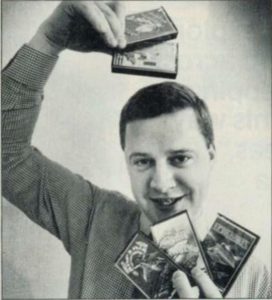

But Lawson wasn’t happy with the royalties he was getting from Bug-Byte, and so he and his friend Mark Butler decided to strike out on their own as Imagine Software in the fall of 1982. His first time out as an Imagine programmer, Lawson came through once again. Indeed, many will tell you that Arcadia, the first game Imagine released, was the best game they ever released. Another space-shoot-em-up for the Spectrum, this one was more frenetic, more intense, and had better graphics than anything Lawson had done before. “I’d buy it just to watch the graphics,” wrote one reviewer.

Meanwhile Everiss too was getting frustrated with Bug-Byte. The two Oxford boys who had the final say there were far more conservative at bottom than he was. They insisted on going everywhere in the tailored suit and tie of traditional British businessmen, a stance that immediately signaled their difference from the scruffy kids of the Microdigital scene who worked for them. And they balked at Everiss’s more outlandish ideas about populist marketing, like his scheme to hire a slate of sexy models — never mind the cost! — to star in a newspaper-and-television publicity blitz.

By the time the contract binding him to Laskys ran out, Everiss was itching to find a full-time gig with a software publisher who would give him carte blanche to implement all of his ideas about consumer software as the music industry of the future. The nascent Imagine Software, founded by two talented kids whom he knew well and who were accustomed to taking their instructions from him rather than the other way around, seemed just the ticket. Imagine seemed a blank slate waiting for his signature. In January of 1983, he joined the infant company, which at that point still sold Arcadia only via mail-order.

That Imagine shared a name with the most famous song by one of Liverpool’s four most famous sons was no accident. Interestingly, it was Lawson, ostensibly the introverted coder of the trio, who had come up with the name, and, indeed, who was most fond of explicit comparisons with the Beatles in general. But Everiss, for this part, had little trouble embracing Lawson’s vision of turning the company into pop culture’s next Beatles, all the while “taking Scousers off the dole.” No one would ever accuse these two young men — or their third partner Mark Butler — of dreaming small dreams.

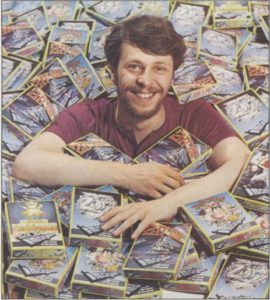

They unquestionably had a hot game on their hands in Arcadia, but a hot game alone wouldn’t be anywhere near enough to fulfill the trio’s ambitions for Imagine; that would depend on marketing, distribution, and image-making at least as much as it would on the games themselves. Everiss recognized that the key to making a mass-market phenomenon of computer games was getting them from specialty shops like Microdigital into the mainstream High Street shops. In the Britain of the 1980s, this latter could mean booksellers like WH Smith, consumer-electronics chains like Dixons, even chemists like Boots, all of whom had set up computer kiosks in some of their locations to commemorate 1982, the government’s official and much-hyped Information Technology Year. Continuing the obsession with presentation and packaging that had marked his association with Bug-Byte, Everiss made sure that Imagine’s games wouldn’t look out of place in such environs. Then, using all the insights he had acquired as a retailer, he worked the phones relentlessly to get them onto the shelves in all three of the aforementioned chains. He also called up toy shops, newsagents, and corner shops, offering them freestanding spinners of games they could simply take out of the box and stand up by the door. “Most said get lost, but some would say yes,” he remembers. When those who did say yes started to turn a tidy profit, even the naysayers began to ring him up to change their tune. In small towns and villages all over Britain, Imagine games, sold from such humble locations as these, were the only ones immediately available to school-age punters during much of 1983. It would take some months for the rest of the industry to catch on to Everiss’s tricks. And by the time the competition did start duplicating his inroads into rural Britain, Everiss had hired people who spoke French, German, Italian, and Spanish, and set them to work getting Imagine’s games into stores on the Continent.

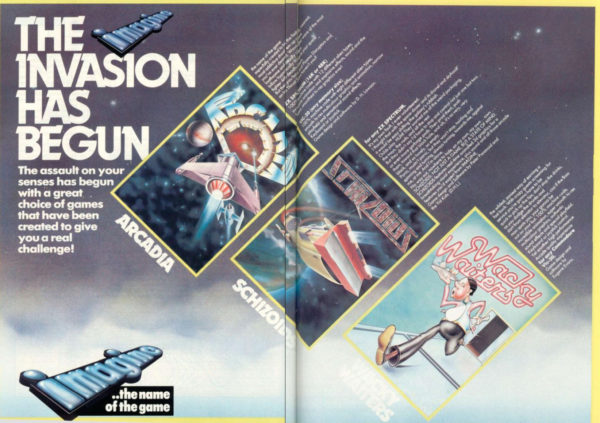

In advertising as well, Imagine set new standards. Stephen Blower, an artist and friend of the core trio, set up an ostensibly independent advertising agency called Studio Sing to manage the company’s public relations, in return for a 10-percent stake in Imagine proper. They would buy six-page spreads at the center of magazines like Computer and Video Games which popped off the page like nothing else between the covers. Almost from the moment that Everiss came on board, the name of Imagine was inescapable in the trade press. “They can only be described as having exploded onto the market,” wrote the magazine ZX Computing.

But that was just the trade press. In keeping with his mass-market ambitions, Everiss wanted to make the name of Imagine Software just as popular in the tabloid press. And the fuel that the tabloids ran on was personality. Newspapers were increasingly full of generic stories of teenage computer geniuses who were making good money out of their bedrooms writing games. If he could give the tabloids a single specific, memorable personality fitting that mold, someone they could really latch onto as the symbol of his generation, Everiss knew that Imagine would be rewarded with a deluge of exactly the sort of press they craved. Yet Dave Lawson, the one person at the company who most obviously fit the role, didn’t relish the prospect, said he was still too busy coding games to take on the full-time job of being the face of Imagine. Meanwhile the more extroverted Mark Butler was, like Everiss himself, a businessman rather than a coder, and that stubborn fact rather took the shine off the prospect of using him for the part. So, Bruce Everiss the would-be Svengali still lacked his star; he was a Brian Epstein without any Beatles of his own. Fine, said Everiss. If he didn’t have a coder star to hand, he would simply have to invent one. Enter one Eugene Evans.

Evans was yet another of those kids who hung around Microdigital, working the occasional Saturday when the shop needed an extra pair of hands, playing with the computers and goofing off when it didn’t. Only 16 years old, he’d learned a bit of coding, but was far from brilliant at it; mostly he just liked to play the latest games and chat about them with the other blokes. Still, Everiss thought he had a certain something that made him perfect for the central-casting role of Teenage Hacker. He was articulate, he was funny and easy to talk to, and he was, at least as Everiss remembers it, “far better looking than David and Mark.” Everiss thought he saw similarities to the young John Lennon — the perfect mascot for a Liverpool company trading under the name of Imagine.

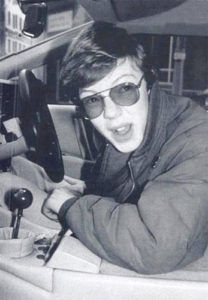

As an artificial persona of Everiss’s creation, the Eugene Evans the media came to know was in reality more Monkee than Beatle. Nevertheless, he played his part to perfection. With Everiss’s tireless publicity machine and his own considerable charm behind him, Evans was suddenly everywhere in 1983, a human-interest story everyone scrambled to cover. Everiss coached him carefully to convey the desired message of the working-class Scouser made good. After growing up in a council house, went the narrative, talent and hard work had made him an unexpectedly wealthy and increasingly famous young man, of the sort who gets stopped on the street. “I’ve been recognized from my picture,” he said. “People have said, ‘I saw you in the paper. It’s nice to see someone getting somewhere.’ I started as a tea boy in a computer shop and you can’t start from much lower.” Stories abounded in the press about how, despite his earning thousands of pounds every month, Evans’s bank wouldn’t let him have a credit card or even a proper checking account because of his age. So, said the articles, when he went out to buy hundreds of pounds worth of hi-fi equipment he had to pay for it all in cash — and in £5 notes at that, for reasons that were never clearly explained but somehow served to make the story sound even better.

But the Eugene Evans stories the press loved most all had to do with his car. It seemed that he’d bought himself a brand new Lotus, but, being too young to drive, couldn’t do much with it other than enjoy looking at it in his driveway. Asked years later about the topic, Everiss claimed that the car really did exist — but admitted that it “belonged” to Evans only on lease. This anecdote, as we’ll soon see, would come to serve as a metaphor for much of what went on at Imagine.

For his part, Evans seemed less concerned about the car than he was with being accepted by Imagine’s crew of real hackers. When not out giving interviews, he tried earnestly to live up to his press by writing games. The results ranged, in Everiss’s words, from “tolerable” to “a travesty.” A natural with the media he perhaps was; a natural programmer he most definitely was not.

When the computer magazines would visit Imagine, the articles and especially the photographs would wind up taking on the aspirational character of a gentleman’s lifestyle magazine. Here, Mark Butler takes his racing bike for a spin. The caption for this photo in Crash magazine describes him as Imagine’s “millionaire founder.”

If Butler and Lawson resented this poseur, they never made it obvious. It did make a certain perverse sense to have Imagine’s coder star be someone who didn’t actually do a lot of coding, thus freeing up the real coders to do what they did best. And besides, Butler, Lawson, and Everiss all had more than enough to keep them entertained as they threw themselves with enthusiasm into a lifestyle of conspicuous consumption. “The money means nothing to me,” Lawson dutifully claimed, as artistic types are expected to do in these situations. “It’s the satisfaction of being the best.” Maybe that was true — but the things he bought with the money, like the £34,000 Ferrari Mondial that he started driving to work, certainly seemed to have their appeal. Butler opted for a BMW 735i and a customized racing motorcyle, while Everiss went with a Ferrari 308 GTS. “We are a dynamic industry,” said the latter, “so we all drive dynamic cars.” Imagine took to handing out new cars as rewards for finishing tricky projects on time, the way other companies might give a gift card for a fancy restaurant. Their parking garage was soon filled with Ferraris, Porsches, and Lotuses, prompting many in Liverpool to joke that Imagine alone had managed to double their town’s population of exotic sports cars in a matter of months. To this day, when people who were around the British games industry back in the day think of Imagine, the cars tend to be the first image that comes to mind.

Yet Imagine’s taste for excess went far beyond the cars they drove. They leased an entire floor of a newly renovated building on Sir Thomas Street, colloquially known around Liverpool as “the Glass Tower,” for what they proudly referred to as their “world headquarters.” Programmers, seeing the tales of Eugene Evans in the tabloid press and even from time to time on the telly, flocked to the place in search of their share of all that filthy lucre. Imagine’s legend was already becoming such that the reality could be disappointing. A typical job seeker was one Chris Butler:

There was a TV Eye program on them where they claimed that Eugene Evans was earning 35 grand a year. And I thought, “Oh, yeah, that’ll suit me,” so I wrote off to them, and they said, “Yeah, yeah.” So I went up there and said, “What kind of salary are you going to offer me?” And they said, “Five grand.” I could get more by working in a bank in Southend.

Butler didn’t take the job, although he would go on to a career programming games for other companies.

But a lot of programmers did accept jobs, along with a support staff of secretaries, artists, salespeople, and PR reps, ballooning Imagine’s employee roll from two at the beginning of 1983 to more than 100 by the beginning of the following year. Most of the support staff knew nothing about computers or computer games. Indeed, the old dream of using computers to take Scousers off the dole seemed rather in danger of getting drowned under a deluge of degreed professionals. Yet the core trio claimed they had no choice but to start bringing in such folks. They considered themselves to be building a new form of popular media, not a technology company, and thus to need their growing collection of degree-holders in fields as diverse as business management and psychology; the latter group were there to study players in the hope of “producing more playable, more addictive games.” Some of the schemes that were hatched were kind of hilarious. “Imagine was looking at alternative input devices,” Everiss would later claim, “including electrodes to monitor brain waves and thus allow thought control of games.”

Imagine continued constantly to drive home their preferred parallels with the field of pop music during the 1960s, claiming as stridently as ever that they would foster the British Invasion of the 1980s. In a sentence that reads like it was dictated to him by Everiss, a wide-eyed young journalist from the popular Spectrum magazine Crash wrote that “Bruce Everiss and Imagine have created an awareness first in Liverpool and now throughout the world about British games software.” While the part about Liverpool was certainly true enough, that business about “throughout the world” was an eyebrow-raising assertion indeed, given that nothing Imagine made had yet been exported any further than Western Europe. But then, to hear Imagine tell the story Britain alone seemed to have more than potential enough for now. Everiss predicted that a Speccy game — presumably one from Imagine — would sell 1 million copies in Britain alone before the end of 1984, in keeping with an overall market he expected to double in size each year for the foreseeable future. “It’s the new mass market,” he said, summing up in those five words Imagine’s entire business strategy. He believed the most dangerous competition for Imagine would come not in the form of the other existing software publishers but, predictably enough given Imagine’s fixation on the music industry, in that of the record companies who must inevitably decide sooner or later to jump on this new bandwagon. “The record companies are experiencing a big drop in sales because more and more young people are becoming bored with pop and turning to games on home computers,” he said, in a comment which had to strike even the most fervent computer boosters as smacking more than a little of wishful thinking.

And yet, if Imagine was telling the truth about their business perhaps Everiss’s claim wasn’t so outlandish. The numbers that came attached to Imagine’s claims of success were astronomical, dwarfing those of any other British software house. They claimed to have earned £6 million in their first six months. The core trio of Butler, Lawson, and Everiss, said trio themselves claimed, were each worth £10 million by the end of 1983. And many of Imagine’s employees, to hear the same three gentlemen tell the tale, weren’t far behind.

In addition to the inescapable Eugene Evans, a second carefully groomed media favorite was John Gibson. Another working-class bloke made good of the sort Everiss so loved to highlight, Gibson in earlier years had played in a rock band, driven a chemist’s van, worked as a social-security officer, and tried to make a go of it as a self-employed carpenter specializing in suspended ceilings. Mud, the band he had played with back in his school days, had later gone on to release the best-selling British single of 1974 among other hits. He’d been saved from a lifetime of stewing over that missed opportunity when he’d discovered computers, learned to program them, and come to Imagine to make games. Now, he drove to work every day in a Porsche. The press loved one anecdote in particular about Gibson: that he, being the only person at Imagine over thirty years old, was called “Granddad” by all his colleagues. “I can’t believe my luck,” he said, “especially at my age,” evidently feeling every one of his 36 years every time he climbed out of his Porsche in the Imagine parking garage.

Gibson was unquestionably a better coder than Evans — Evans “can play the games I’ve written better than I can,” he once said noncommittally when an unsuspecting journalist served up a chance to compliment the latter’s skills — yet it was hard to fathom how he could be making so very much money from the games he churned out. The harsh fact was that Gibson’s games, as most of the teenage critics who bought them agreed, never really rose above the level of competent. His first, Molar Maul, was more notable for its bizarre theme — it stuck you inside someone’s nasty morning mouth, expecting you to ward off plaque attacks with toothbrush and toothpaste — than for its gameplay. The next, Zzoom, was just another shooter, while the third was the poorly received Stonkers, an attempt at delivering a strategic war game that was virtually unplayable in concept and horrendously buggy in execution, rather leaving one with the impression of a programmer and game designer completely out of his depth.

And as Gibson’s games went, so went those of Imagine as a whole. Butler, Lawson, and Everiss wanted the company to publish two new games every month, and their programmers worked hard to meet this goal. To help them, Lawson put together a state-of-the-art development system, in which programmers could do all of their coding on SAGE IV workstation computers, boasting 1 MB of memory and hard disks, instead of the tiny cassette-based machines the games must eventually run on. But if the workstations helped them to make games faster, they didn’t really seem to help them make games that were better than the competition in terms of anything other than their packaging and advertising. Even Lawson seemed to have grown a bit lazy after Arcadia, preferring to play the gentleman-about-town in his Ferrari and generally enjoy the good life rather than taking the time to make more games of similar quality. One Bruce Everiss quote was perhaps inadvertently telling: “Like pop records and tapes, games must have imaginative and colorful covers to attract sales. Almost as much time is spent designing the covers, packaging, and publicity materials as devising and testing the games themselves.”

In the summer of 1983, a new company with the linguistically tortured name of Ultimate Play the Game — possibly a play on Imagine’s favored advertising tagline, “The Name of the Game” — arrived on the scene with an initial spurt of four very impressive games in two months. These titles, whether taken separately or in unison, gave the lie to any lingering claim by Imagine to be the best maker of Spectrum games, full stop. Ultimate took exactly the opposite tack to that of Imagine in terms of public relations, replacing the latter’s ostentation with reclusiveness, and managing in the process to replace their rival almost overnight as the coolest name in Spectrum gaming. While Imagine continued to make a spectacle of themselves, Ultimate quietly delivered groundbreaking game after groundbreaking game from a secret location with a “Private: Keep Out!” sign posted on the door. Meanwhile Imagine’s games seemed to be getting worse over time rather than better, with embarrassing turkeys like Stonkers becoming more and more common.

One didn’t have to be an expert in financial forensics to sense that the numbers didn’t quite add up for Imagine. Their mediocre games had undoubtedly benefited greatly from the distribution inroads engineered by Everiss, but by late 1983 the competition had already done much to erase that advantage, at least in terms of the domestic British market. How could Imagine’s games possibly be selling in such quantities that they could afford to zip about in Ferraris while everyone else puttered around in Fords? When journalists did question them on specifics, the answers they received were never very satisfying. For instance, after Mark Butler made the incredible claim that 70 percent of all Spectrum owners had purchased a copy of Arcadia, Your Computer magazine asked how it could be that such an unprecedentedly popular game hadn’t been all that high in the industry’s official retail-sales charts for some time. Butler answered that this was because most of Arcadia‘s sales were made via mail order — a claim that stood in stark contradiction to Imagine’s other assertion that their Britain- and Western Europe-spanning retail network was one of the biggest keys to their allegedly ongoing success.

Such questions were getting put to them more and more as Imagine powered into the 1983 Christmas season, still only their first as a publisher to retail. Yet even now the trade press’s skepticism wasn’t too pronounced. These “journalists” were mostly just young men who loved games and the computers that played them; they were far from trained investigative reporters. And there remained the tangible proof of Imagine’s success all around them, in the form of fast cars, faster motorcycles, plush offices, and a bevy of well-coifed secretaries who seemed to have been hired on the basis of looks rather than skills. Something had to be paying for all this ostentation, right? To a large extent, the brash young lads of Imagine were living the dream they all shared. No one really wanted to burst the bubble — even if Ultimate’s actual games were a lot better.

But burst the bubble must. And when it happened, the result would be a spectacular crackup that still remains one of the most storied in the long history of games-industry excess, a veritable blueprint for the similar crackups to come. Enormous though the sums connected with Imagine’s failure seemed at the time, the money involved in those later scandals would of course dwarf that of this one. Still, Imagine’s story would have one delicious aspect even they wouldn’t be able to match: it would be captured on videotape.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Rebecca Levene and Magnus Anderson; Your Computer of October 1981, August 1982, January 1983, April 1983, and December 1983; Computer and Video Games of December 1981, May 1983, and February 1984, and the 1984 Yearbook; The Games Machine of August 1990; ZX Computing of April/May 1983; Popular Computing Weekly of January 6 1983, March 3 1983, and April 7 1983; Home Computing Weekly of April 12 1983, May 17 1983, July 12 1983, and December 20 1983; CU Amiga of August 1992; Sinclair User of March 1984 and May 1984; ZZap! of September 1986; Your Computer of April 1983 and November 1984; Crash of March 1984; Times of London of August 16 1983. See also Bruce Everiss’s “A History of the UK Video Game Industry Through My Eyes,” parts 1 and 2. The Commercial Breaks episode on Ocean and Imagine is available on YouTube.)