Henk Rogers returned to Moscow on March 15, 1989, under very different circumstances from those of his first visit of a month before. Then he had officially been a tourist, a complete unknown to ELORG with no right to do business in the Soviet Union; now he had a meeting with Nikolai Belikov and his fellow bureaucrats scheduled prior to his arrival. Then he had traveled alone; now he brought with him an American named John Huhs, a lawyer and fluent Russian speaker with no experience in videogames but heaps of experience brokering complex international deals with insular non-democratic countries like the Soviet Union. Then he had been working, ostensibly at least, as a free agent, trying to secure the handheld rights to Tetris for his own Bullet-Proof Software so he could license them on to Nintendo; now he was working as a more direct proxy for the Japanese videogame giant, hoping to broker an agreement in principle to license the North American console rights to Tetris directly from ELORG to Nintendo. If he could achieve that goal, Minoru Arakawa and Howard Lincoln of Nintendo of America, two of the three most powerful people in videogames (the third being, of course, Nintendo’s overall president Hiroshi Yamauchi), were willing to drop everything and join him in Moscow for the final signing.

When Rogers walked into his meeting with Belikov, he threw Nintendo’s eye-popping offer for the console rights down onto the table without preamble. In addition to a generous royalty, Nintendo would guarantee that ELORG would make at least $5 million from the deal when all was said and done. If, in other words, royalty payments didn’t reach $5 million within a certain time frame, Nintendo would make up the difference out of their own pocket. This was big money by almost anyone’s standards, but in the context of the Soviet Union of 1989 it was an astronomical sum. The offer was intended to turn Belikov’s head, and in this it succeeded magnificently. Previous negotiations had dwelt on relative nickels and dimes: $50,000 here, $100,000 there. Nintendo’s offer elevated the discussion to another financial plane entirely. It was so much more generous than Belikov could have imagined in his wildest dreams that he was highly motivated to get an agreement finalized before cooler heads in the West prevailed. And this, needless to say, was just what Arakawa and Lincoln had intended.

As their initial offer testifies, Arakawa and Lincoln wanted those Tetris rights very, very badly. While their actions were partially motivated by their firm belief that Tetris was one hell of a game that deserved as wide an audience as possible, this was hardly the sum total of what was driving them. Nor did even the profits they expected the game to rake in fully explain their generosity. Unbeknownst to Nikolai Belikov, Alexey Pajitnov, or anyone else in the Soviet Union, the Tetris rights were about to be tossed like the mother of all live grenades into the greatest war the American videogame industry had ever known. The combatants were nothing less than the two most legendary trademarks in videogames. It was the architect of the first great videogame craze versus the architect of the second: Atari versus Nintendo.

The roots of the conflict ran deep. Forbidden from entering the console market by the agreement which had split the old Atari into two companies in the wake of the Great Videogame Crash, Atari Games had tried to content themselves with building standup arcade machines while Nintendo breathed life back into the supposedly dead North American console market. At last, unable to resist that exploding market’s allure any longer, they had formed their Tengen subsidiary to make console games of their own in 1987.

Whatever their personal feelings toward the company, Tengen had known that Nintendo was the only game — or, rather, the only game console — in town. They had thus signed a contract to become an authorized maker of games for the Nintendo Entertainment System in January of 1988. Tengen was limited, like most such licensees, to five games per year, which were to be manufactured by Nintendo at the times and in the quantities Nintendo chose. Therein lay the first concrete bone of contention between the two companies.

When Tengen delivered their first finished games to Nintendo in June of 1988, Nintendo ordered far fewer to be manufactured than Tengen had requested. They pinned the need for the reduction partially on overoptimism on Tengen’s part and partially on a worldwide microchip shortage they claimed was forcing them to scale back all cartridge production. To say the least, their licensee wasn’t convinced. A livid Atari claimed they could have sold ten times as many game cartridges as Nintendo deigned to provide them with, and openly suspected malice aforethought in Nintendo’s whole production-allotment process. Atari decided that in order to thrive again in the console market they must break Nintendo’s stranglehold on the manufacture of cartridges.

The key to breaking through on that front, they realized, was to break the lockout system employed by the NES. Nintendo’s ability to control their captive market without running afoul of antitrust laws hinged on this patented and copyrighted combination of code and circuitry, which prevented unauthorized cartridges from working on the console. If Atari could develop a lockout-defeating technology from scratch, making no use of any of Nintendo’s schematics or documentation, their lawyers believed that they would be legally in the clear to produce their own Nintendo games in whatever quantity they desired, and without paying Nintendo the customary licensing fee.

Unfortunately, reverse-engineering the lockout system was a tall order; it was by far the most advanced piece of a game console that was otherwise years out of date in purely technical terms. At last, they decided to cheat.

The code that operated the lockout system had been registered by Nintendo with the United States Copyright Office, an act which had required Nintendo to send to the Copyright Office a copy of the code. There it was kept under lock and key, inaccessible to third parties — except under one condition: if the code should become the subject of litigation, both sides were entitled to a copy. In other words, had Nintendo accused Atari of violating their copyright on the code, Atari’s lawyers would have been able to request a copy in order to defend their client.

Nintendo had not done any such thing. Nevertheless, Atari filed an affidavit with the Copyright Office in connection with legal proceedings allegedly about to get under way, for which a copy of the code was needed. The affidavit indicated that the code was “to be used only in connection with the specified litigation.” Failing to do their due diligence in verifying Atari’s claim, the Copyright Office complied, providing a copy of the code to be used in a legal case which didn’t exist. Not coincidentally, Atari’s ongoing efforts to reverse-engineer Nintendo’s lockout system finally bore fruit shortly thereafter.

On December 12, 1988, Atari Games filed suit against Nintendo, charging them with monopolistic business practices. “Through the use of a technologically sophisticated ‘lockout system,'” the complaint claimed, “Nintendo has, for the past several years, prevented all would-be competitors, including Atari, from competing with it in the manufacture of videogame cartridges compatible with the Nintendo home-videogame machine. The sole purpose of the lockout system is to lock out competition.” The complaint went on to make note of Nintendo’s stranglehold on the supply of third-party game cartridges: “The impact of Nintendo’s conduct has been to block any competition in the manufacturing market for videogame cartridges compatible with the Nintendo machine.” Atari asked for a staggering $100 million in damages.

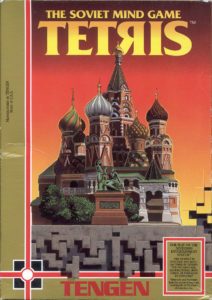

On the same day they filed their lawsuit, Atari announced that they would start manufacturing and selling their own Nintendo games, without involving Nintendo at all or paying them anything at all. Tengen shipped new, unauthorized versions of their three extant Nintendo games — Pac-Man, Gauntlet, and R.B.I. Baseball — using their lockout-defeat technology. And they soon announced another four unauthorized games — Super Sprint, Rolling Thunder, Vindicators, and Tetris — which were to be released in May of 1989. Even more so in its way than the lawsuit, Atari’s decision to start making unauthorized games for the NES was the shot heard round the industry.

The conflict between Nintendo and Atari was a deeply personal one. Whatever Nintendo’s real or alleged legal sins, Atari, barely half a decade removed from their glory days, resented them most of all as the usurpers of what they regarded as their rightful crown. For their part, Arakawa and Lincoln had known Hideyuki Nakajima, Atari’s president, for years, had imagined there was a bond of mutual respect that would prevent him from ever taking a step like this. When Atari had signed on as a Nintendo licensee, they believed they had shown Nakajima exceptional deference, freely divulging, as Lincoln would later put it, “the crown jewels of our business.” In their eyes, then, Nakajima’s declaration of war was a personal betrayal.

It was also nothing less than an existential threat to Nintendo’s entire business model. If Atari got away with this, other publishers would inevitably find their own ways to defeat the lockout system — who knew, maybe Atari would even sell their stolen secrets to them — and the walls around Nintendo’s carefully curated and absurdly profitable videogame garden would be demolished. That scenario must be prevented at all costs. Largely thanks to Howard Lincoln, Nintendo of America already enjoyed a reputation for ruthlessness when their interests were challenged. Now, Arakawa told Lincoln to stop at nothing to quell Atari’s uprising. Atari had opted to go to total war with, in Lincoln’s colorful diction, “a tiger who will skin you piece by piece.”

Nintendo’s legal response to Atari was swift, multi-pronged, and comprehensive. On January 5, 1989, they filed a counter-suit alleging breach of contract (for reneging on Tengen’s existing agreement to sell authorized Nintendo cartridges) and trademark infringement (for printing the Nintendo logo on Tengen’s unauthorized packaging). More audaciously, the suit alleged that Atari had violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, better known in law-enforcement circles as RICO and normally applied to gangland money-laundering operations, in setting up Tengen as essentially a shell corporation with the intention of defrauding Nintendo. Another suit, filed on February 2, accused Atari of patent infringement of the NES lockout system.

But the courts were hardly the only weapon which Nintendo, the company which for all intents and purposes was the American game-console industry, had at their disposal. They took to calling the major retailers, telling them that selling products “which infringe Nintendo’s patent or other intellectual-property rights” would have dire consequences for their supply of official Nintendo hardware and games. “Companies would not carry our games because there was pressure from Nintendo which could jeopardize their business,” says Nakajima. “Even the big companies like Toys ‘R’ Us couldn’t stand up to them.” Atari executive Dan Van Elderen imagines the way a conversation between a major retailer and Nintendo might have gone: “You know, we really like to support those who support Nintendo, and we’re not real happy that you’re carrying a Tengen product. By the way, why don’t we sit down and talk about product allocations for next quarter. How many Super Marios did you say you wanted?” “If a retailer carried Tengen games, their Nintendo allocations would suddenly disappear,” remembers one retail buyer who was caught in the crossfire. “Since it was illegal, there were always excuses: the truck got lost, or the ship from Japan never arrived.” Tengen was slowly but methodically squeezed out of retail.

A third theater of battle was the press, which the combatants used to lob statements back and forth, jockeying for advantage with the public and especially with the American political establishment, many of whose members had long expressed concern at their country’s longstanding trade deficit with Japan. Atari tried to frame a folksy narrative of a domestic upstart just looking for a fair shake against the calculated malfeasance of a shifty-eyed foe from the Orient: “Let’s say you buy a Ford, and the company says, ‘If you buy a Ford automobile from us, you have to buy Ford gas.’ That’s not the way business is done.” Nintendo replied by claiming — being partly if not entirely truthful about their motivations — that they had put their controls in place to keep the junk games that had done so much to precipitate the Great Videogame Crash of 1983 off the market this time around: “It was the only way we could ensure that there would be consistent, quality software.” Hoping doubtless to curry favor, some American publishers who were closely identified with Nintendo parroted this company line, among them Acclaim Entertainment: “Nintendo is trying to make this into a category, not a fad, where videogaming becomes another part of our entertainment life.”

But the majority of the American software industry stood — tacitly at least — with Atari. Indeed, Atari’s cause was increasingly becoming that of the American software industry as a whole — by which I mean many companies that had never heretofore made console games at all, that had concentrated on the less volatile home-computer market. Yet in recent months, in the face of a Nintendo market that had gone from nothing to three times the size of the total American market for computer games with incomprehensible speed, it had been hard for the computer-game publishers to resist the lure of the other side. Most of those who jumped into publishing agreements with Nintendo were frustrated by the same restrictions and policies that so infuriated Atari. The whole enterprise seemed consciously engineered to let them make some money but never too much — and certainly to keep them from ever making a truly iconic Nintendo game to rival the likes of Super Mario Bros.

The Software Publishers Association, the traditional American software industry’s biggest lobbyist and trade group, left no doubt where it stood on the question: “The SPA believes that Nintendo has, through its complete control and single-sourcing of cartridge manufacturing, engineered a shortage of Nintendo-compatible cartridges. Retailers, consumers, and independent software vendors have become frustrated by the unavailability of many titles during the [1988] holiday season, and believe that these shortages could be prevented by permitting software vendors to produce their own cartridges.” The SPA warned ominously and to some extent presciently of what the walled-garden philosophy of software marketing could come to mean if it spread further: “We don’t want any computer company to get the idea that what Nintendo is doing would be acceptable in the computer business. Software is an intellectual property that thrives in an unrestricted environment.”

That said, few companies were willing to attract the attention of the Nintendo tiger by stating their views too stridently or too publicly, much less by taking the sort of aggressive action Atari Games had opted for. There was, however, one notable exception.

On January 31, 1989, the other Atari — the home-computer company run by Jack Tramiel and his sons — filed their own suit against Nintendo, asking that the latter be forced to pay the towering sum of $250 million in damages. At issue this time was Nintendo’s policy of requiring that many licensees not port their games to other systems for two years from the date of their first appearance on the NES. This policy, Tramiel’s Atari claimed, was an abuse of Nintendo’s near-monopoly of the videogame market and thus a violation of antitrust laws. Atari Corporation’s claim to being an aggrieved party in the issue was perhaps debatable; Tramiel’s company produced mostly hardware, not software, and its main strategic focus was its ST line of computers, whose most successful games tended to be dramatically different in character from those which sold best on the NES. It was, in other words, hard to imagine that the lack of hot Nintendo-style games on the Atari ST was a primary reason behind its lackluster North American sales. But Jack Tramiel had a long history of using the courts as business competition by other means, and, gauging the political mood in the country with respect to Japanese imports, he thought he smelled blood in the water here.

So, it was now the two Ataris against Nintendo — the past of videogames against their future, one might say. Thematics aside, the two Ataris made for some very unexpected bedfellows. Each part of the old, monolithic Atari felt that they were the only part truly worthy of carrying the name’s legacy onward. To put it bluntly, the two companies “don’t like each other,” admitted Atari Games’s Dan Van Elderen. But, as they say, the enemy of my enemy…

Isolated in Moscow, Nikolai Belikov was unaware of this dramatic backdrop to Nintendo’s generous offer for the Tetris console rights. From his perspective, the only thing preventing the negotiation from moving forward immediately was the promise which he had made to Kevin Maxwell to give Mirrorsoft an opportunity to bid on the rights. Thankfully, the Russians hadn’t heard anything at all from Mirrorsoft since Maxwell had departed Moscow over two weeks ago.

On the same day that Henk Rogers first presented Nintendo’s offer, Belikov fired off a telex to London, saying that ELORG was about to sign a deal for the console rights to Tetris and that, in accordance with the arrangement he and Maxwell had arrived at, Mirrorsoft urgently needed to send their own best offer — if they wished to make an offer at all, that was. He gave them exactly 24 hours to do so, an intentionally impossible time frame. When the deadline expired, Belikov considered himself to have done his legal duty. Now nothing lay between him and a deal worth at least $5 million.

When word came to Arakawa and Lincoln from Rogers that an agreement for the console rights looked very possible, they scrambled to secure the visas and airplane tickets they needed to come personally to Moscow. This latest round of Tetris negotiations offered not just the opportunity to secure an all-but-guaranteed massive hit for Nintendo, but also that of taking away an all-but-guaranteed massive hit from Atari. Neither Arakawa nor Lincoln was an especially forgiving man, and they relished this opportunity with their every last fiber of vindictiveness. Their preparations for their journey smacked more of a spy thriller than a typical business trip. The comings and goings of two men such as them within what was once again a multi-billion-dollar American videogame industry hardly went unobserved even when the industry wasn’t racked by total war. On the contrary: their every statement, action, and, yes, movement was closely scrutinized for clues to what Nintendo might do next. Arakawa and Lincoln thus felt compelled to slip away in the dead of night, telling only two of their closest confidants where they were going and why.

They arrived in Moscow on Sunday, March 19. As befit the sense of occasion that surrounded their visit, Henk Rogers forewent the taxis that were his usual mode of transportation around Moscow in favor of picking them up at the airport in a big black Mercedes he had managed to rent at an exorbitant price. The two huddled in the back seat, jet-lagged and bleary-eyed, and marveled at the Mirror World outside the windows, which Lincoln said reminded him of the mean streets of old black-and-white gangster films. Their self-appointed chauffeur, feeling himself by comparison an old hand with Moscow life, merely smiled and nodded. At the hotel, Arakawa and Lincoln were given a room with a single bed, a disconnected stove, and a refrigerator without a door. Don’t complain, Rogers told them; it can only get worse.

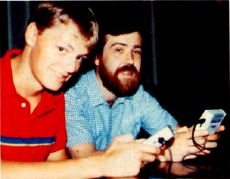

Whatever their other prowesses as negotiators, Arakawa and Lincoln weren’t gifted with Henk Rogers’s all-but-irresistible charm. Arakawa was reserved, stoic, even shy among new people, while Lincoln, who looked every inch the corporate lawyer he was, made the most of his native suspicious nature as Nintendo’s attack dog, willing to challenge every point and question every assertion in trying to secure for his company every possible advantage. Alexey Pajitnov, for one, sensed the change in the atmosphere around the table as soon as they all entered the conference room the next day.

Still, it was fascinating in a way to watch Belikov and Lincoln, two sly old foxes with far more in common than the gulf of culture, language, and politics that lay between them might suggest, sniff one another out. Lincoln questioned Belikov long and hard about the previous deal with Stein and the potential trouble it might present. Belikov, meanwhile, notwithstanding the incredible offer that lay on the table, pressed relentlessly for further advantage, persisted in testing every boundary. Apparently not understanding how unique Tetris was, he seemed to see game design as a commodity amenable to the typical Soviet model of mass production, proposing that Nintendo and ELORG set up a joint subsidiary to crank out many more games. Apparently not understanding that the key to Nintendo’s control of their walled garden was their ownership of the means of production of game cartridges — the very thing they were fighting so savagely to maintain far away in the United States — he proposed that the Tetris cartridges be manufactured by ELORG in the Soviet Union, a recipe for quality-control disaster if ever there was one. Then he proposed that ELORG make actual Nintendos in the Soviet Union for sale behind the Iron Curtain. The most surreal moment of the talks came when a cosmonaut trooped in to pitch an idea for plastering the Nintendo logo all over Soviet rockets; when the Soviet Union embraced capitalism, it seemed, it really embraced capitalism.

Another bizarre incident hearkened ironically back to that earlier pivotal instant when Henk Rogers had produced Bullet-Proof Software’s “pirated” Nintendo Famicom version of Tetris to gasps all around the conference table. Wanting to demonstrate how adept his people were at this consumer-electronics thing, one of the Russian bureaucrats reached under the table and came up with a Soviet knockoff of a Donkey Kong standalone handheld game which Nintendo had released back in 1982. In its Soviet form, it was bereft of any acknowledgment of its origins — and bereft of any agreement to pay Nintendo royalties for it. Under normal circumstances, such a thing would have set Howard Lincoln into a paroxysm of enraged threats. But today, managing to see the bigger picture, he swallowed hard and held his tongue with difficulty.

To be fair to Belikov, many of the kookier ideas that he was forced to pitch likely didn’t originate with him. In this era of perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev had tasked the masterminds of his nation’s economy, so long accustomed to looking inward to quotas and five-year plans, with looking out, with finding areas where the Soviet Union could compete with the other members of the community of free nations Gorbachev was intent on joining. Computer software had always seemed like an area with real potential in this regard, responsive as it seemingly was to the country’s long tradition of mathematical excellence. And now here was the Tetris deal. As a game rather than a more “serious” piece of software, it perhaps wasn’t the completely ideal vehicle for Soviet software’s coming-out party, but it would do. As soon as that $5 million figure started to spread through the Soviet bureaucracy, Belikov’s negotiations over what had heretofore been regarded as a silly little game — a minor transaction at best — took on a dramatically higher profile. Lots and lots of people with lots of different agendas were now trying to muscle their way into the room with these foreigners who so evidently had more money than sense. Lincoln batted away each crazy proposal as politely as he could, and kept trying to steer the discussion back to the deal that was already on the table.

The atmosphere was warmer that evening when Rogers, still playing the role of chaperone and tour guide, located the only sushi restaurant in Moscow and took Arakawa, Lincoln, Pajitnov, and Nintendo’s legal consultant John Huhs out for dinner there. Pajitnov was skeptical of the notion of eating raw fish, but soon got with the program — at least until he popped an entire ball of wasabi into his mouth just ahead of his companions’ urgent warning cries, nearly causing his head to explode. Back at the Pajitnov family apartment, Arakawa gave the children a prototype Game Boy with a prototype of Tetris in the cartridge slot, telling them that they were now quite possibly the first people in the entire Soviet Union to own a Nintendo product. Pajitnov still stood to gain absolutely nothing from this game that so many others were now confidently expecting to earn them millions, but he did appreciate the attention and respect he was shown by the Nintendo delegation, so different from Robert Stein and the ELORG bureaucrats who did little more than tolerate his presence at the negotiating table. And he took Henk Rogers at his word that someday soon he would find a way to get him his financial due — if not with Tetris, than with the next game he designed.

A contract giving Nintendo exclusive worldwide-except-for-Japan console rights to Tetris was signed on March 22, 1989, alongside another giving the Japanese rights to Rogers, thus fully legitimizing in the eyes of ELORG the Bullet-Proof version of Tetris that had started this whole ruckus. Two heavyweight bureaucrats, the head of the State Committee for Computer Systems and Informatics and the head of computer research at the Soviet Academy of Sciences, came out to witness the signings, which were conducted with some pomp and circumstance. To commemorate the occasion, Rogers, who in his standard inimitable fashion was now wheeling and dealing on the Moscow black market like a native, presented Arakawa and Lincoln with tickets for that evening to the Bolshoi Ballet. Much to their amazement, Mikhail Gorbachev himself showed up for the performance — and took a seat that was worse than theirs. That was Henk Rogers for you.

From being the property of Robert Stein in their totality barely a month earlier, the rights to Tetris had now been sliced and diced into a whole pile of discrete parts. The computer-game rights lay with Mirrorsoft in Europe and, through Mirrorsoft, Spectrum Holobyte in North America and Bullet-Proof Software in Japan. The arcade rights lay with Atari Games in North America and Europe and, through Atari, Sega in Japan. The worldwide handheld rights lay with Bullet-Proof, who planned to use them to let Nintendo bundle a copy of Tetris with every Game Boy sold when the new gadget came to North America in four months or so. And now, as a product of this latest round of negotiations, the non-Japanese console rights belonged directly to Nintendo, the Japanese console rights to Bullet-Proof.

This, anyway, was the new world order according to ELORG and Nintendo. But there was soon trouble from the parties whose earlier deals had been retroactively voided, just as Rogers had warned Belikov there would be the previous month.

On the morning of March 22, even as the contract-signing ceremony was about to get under way, a belated response had finally arrived to the telex which Belikov had sent to Mirrorsoft six days before. In the message, Jim Mackonochie of Mirrorsoft, adopting a posture of bemused confusion, said that Mirrorsoft didn’t need to bid for the console rights because they already possessed them. His obvious intention was to pretend that the disastrous meeting between Belikov and Kevin Maxwell had never happened, and to hope that thereby the old status quo would be allowed to reassert itself. But he learned that that most definitely wasn’t a possibility later the same day, when Belikov sent a reply stating that the console rights had never been Stein’s to license to Mirrorsoft, and that those selfsame rights had in fact just been licensed to Nintendo. To rub salt into the wound, Belikov also dropped the bombshell that the handheld rights already belonged to Henk Rogers.

The Mirrorsoft camp’s response was predictably swift and aggressive. Evidently not recollecting how well his last decision to shove Mackonochie aside had gone, Kevin Maxwell jumped personally back into the fray the very next day with a telex telling Belikov he was “in grave breach twice over of our agreements with you.” Having apparently remedied the ignorance that had led him to call the Bullet-Proof Tetris a pirated version on his last trip to Moscow, he wrote that “we already hold the worldwide rights to Tetris on the Nintendo family computer. Indeed, we have been marketing it accordingly, [through] Bullet-Proof Software in Japan since January 1989.” But he was willing, he graciously conceded, to come to Moscow to meet once again with Belikov and learn from him “how you intend to remedy your double breach of our agreement.” Should Belikov refuse to invite him to such a meeting, he warned of legal and political — yes, political — consequences.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Robert Maxwell. The latter was so chummy with the Kremlin that questions would later surface over whether he had acted at times as a Soviet spy.

He wasn’t just blowing smoke. His father, Robert Maxwell, was an absurdly well-connected man, the ruler of a communication and publication empire that spanned the globe and that had placed him on a first-name basis with countless current and former heads of state. When told by his secretary that “the prime minister” was on the phone for him, legend has it that Maxwell would ask, “Which one?” His Rolodex contained the home address and phone number of one Mikhail Gorbachev, just as it had Gorbachev’s predecessors Yuri Andropov, Leonid Brezhnev, and Nikita Khrushchev.

After the Nintendo delegation returned home from Moscow and it became clear to Kevin Maxwell that Belikov had no intention of granting him his mea-culpa meeting, he went to his father to explain what the Russians had done to him, eliciting a desk-pounding fit of rage: “They won’t get away with it! Rest assured of that!” Robert Maxwell wrote directly to the highest levels of the Kremlin, issuing a thinly veiled threat to the many investments he was making into Gorbachev’s new Soviet Union: “We attach high importance to our excellent commercial relations with the Soviet government and many leading agencies in the fields of information, communications, publishing, and, indeed, pulp and paper production. We face the prospect of all this being jeopardized by the unilateral action of one particular agency.” Nice economy you’re building there, Gorbachev, ran the subtext. It’d be a shame if anything happened to it — and all because of one silly videogame.

Maxwell contacted the secretary of state for trade and industry within Britain’s own government, pushing him to place the Tetris issue on the agenda for an upcoming summit between Margaret Thatcher and Gorbachev. Alexey Pajitnov’s little game of falling shapes was now threatening to impinge on agendas at the highest levels of international statecraft. In late April, Maxwell flew to Moscow to meet personally with Gorbachev, ostensibly to discuss his growing number of publication ventures within and on behalf of the Soviet Union. But he brought up the issue of Tetris there as well, and claimed that before he left Gorbachev assured him that he would personally take care of the issue of “the Japanese company” for him.

In actuality, though, Gorbachev did little or nothing, presumably judging that Maxwell wouldn’t really blow up deals potentially worth billions in the long run over a videogame-licensing spat. Still, plenty of others within the Soviet government — among them many representatives of the hard-line communist order that was at odds with Gorbachev — wanted an embattled Belikov to back down and give Maxwell what he wanted.

When Howard Lincoln returned to Moscow about a month after his first visit for a follow-up meeting, a tension that verged on paranoia was palpable around the conference table. Belikov spoke of “calls from the Kremlin, calls from people who never before knew we existed. Many of them have shown up to examine our records and to question us on this deal. We have told them we have done the right thing. We have stood up to them, but we do not know what will happen.” There were even rumors that the KGB had been put on the case to dig up dirt on Belikov and his colleagues at ELORG, rumors of bugs in telephones and men in descriptly nondescript trench coats trailing people through the streets. Belikov had hired a pair of personal bodyguards for protection.

He clung to a simple but potent line of argument against his persecutors: Gorbachev had said that producers in the Soviet Union needed to have a degree of economic freedom, needed to make decisions in response to the market rather than a hidebound bureaucratic class. That was what perestroika, the buzzword of the age, was all about. He, then, was just doing perestroika. Nintendo had offered ELORG a better deal, and he was bound — duty-bound by perestroika, one might say — to take it.

Helping Belikov stay strong was the fact that he and Howard Lincoln had gone from cagey adversaries to something approaching friends. In the months after signing their deal, Belikov arranged for Lincoln and his son to take a private tour of Star City, the heart of the Soviet space program. He took Lincoln on a traditional Russian fishing trip — “traditional” in this case indicating much more vodka-drinking than fish-catching. He felt a bond with Howard Lincoln and also Henk Rogers, two men who had talked straight to him and treated him as an equal, that he most definitely didn’t feel with Robert Stein or the Maxwell clan. He felt that Lincoln and Rogers had been in his corner, so he would stay in theirs. Crusty old bureaucratic knife fighter though he was, his sense of loyalty ran surprisingly deep.

While Belikov was weathering the storm unleashed by Robert Maxwell upon Moscow, Arakawa and Lincoln were left to deal with the issue of Atari, Mirrorsoft sub-licensee of the Tetris rights, in the United States. It seems safe to say that they relished their situation far more than their Soviet partner did his, not least because it afforded them the luxury of going on the offensive in yet one more way against their bitterest enemy. With delicious satisfaction, Lincoln drafted a cease-and-desist letter that was sent to Atari on March 31, saying that the console rights to Tetris belonged to Nintendo rather than to Tengen, and that the latter thus needed to give up their own plans for Tetris if they didn’t wish to spark another legal battle in the ongoing war. He knew, as he would later put it, that Atari “would go nuts” when they received the letter. On April 6, Nintendo announced via an official press release their plans to release their version of Tetris for the NES that summer. Atari took the bait, suing Nintendo for infringing on their licensing deal with Mirrorsoft on April 18. They honestly believed that the rights they had licensed from Mirrorsoft were perfectly legitimate — “There was no inkling that we were in the wrong,” Tengen head Randy Broweleit would later say — and they had no intention of lying down for Nintendo. Quite the contrary. Having engulfed so much of the American videogame industry already, it hardly surprised anyone that the war between Atari and Nintendo had now sucked Tetris as well into its maw.

Ironically, the version of Tetris which Tengen was finalizing against the will of the game’s designer was by far the best version of the game that had yet been created. Indeed, plenty among the Tetris cognoscenti will tell you that the Tengen Tetris still stands among the best versions ever created, far superior to the versions Nintendo was preparing in-house at the time of its release. Tengen had assigned Ed Logg, creator of iconic arcade games like Asteroids, Centipede, and Gauntlet, to head up a team that wound up spending three person-years on the project, a rather extraordinary amount of time in light of what a simple game Tetris really was. Under Logg’s stewardship, Alexey Pajitnov’s core design took on a much more polished look than it had enjoyed to date. The pieces were no longer solid blocks of color, but were given texture and a pseudo-3D appearance that made them look more like falling blocks than falling abstractions, harking back to the physicality of the pentomino puzzles that had inspired the game. Logg also added a head-to-head competitive mode to the game, and an innovative cooperative mode in which two players could work together to clear away lines. And he made the speed of the falling shapes increase slowly and subtly the longer you played, instead of taking a more noticeable, granular leap only when you went up a level. Whatever you could say about the circumstances of its creation, taken purely on its own terms it was truly a Tetris to be proud of.

It needed to be great. Tengen was counting on this game becoming an unstoppable force that would bust right through the blockade Nintendo was erecting around their lifeline to retail. The launch was as lavish as they could make it, beginning with the game’s unveiling at Manhattan’s Russian Tea Room restaurant. As that location would imply, the line of marketing attack developed by Mirrorsoft and Spectrum Holobyte was employed once again by Tengen. In their hands, though, it came to read a little tone deaf, being amped up with far more testosterone than the game destined to go down in history as the very personification of a non-violent, casual puzzler really had need of. “It’s like Siberia, only harder,” ran one tagline. “It’s the nerve-wrackingest mind game since Russian roulette,” ran another. A third said it should only be played by “macho men with the first-strike capability to beat the Russian programmers who invented it. If you can’t make the pieces fit together, an avalanche of blocks thunders down and buries you weaklings!”

But, overheated rhetoric aside, Tengen clearly saw the potential of Tetris to expand the Nintendo demographic beyond boys and teenagers, buying full-page spreads in such mainstream non-adolescent publications as USA Today. And, now that they controlled the means of Nintendo cartridge production, they weren’t going to be caught out by any shortage on that front. They ordered an initial production run of fully 300,000 Tetris cartridges, at an expense of $3 million.

The Tengen Tetris was released on May 17, 1989. It took Nintendo exactly eight days to sue in response; in combination with Atari’s earlier suit against Nintendo, this latest legal salvo meant that each company was now accusing the other of making or planning to make what amounted to a pirated version of Tetris. While American courts tried to sort through the dueling lawsuits, American gamers faced the prospect of deciding between dueling versions of Tetris on the NES, each claiming to be the one and only legitimate version.

Alexey Pajitnov’s little game of falling shapes, having already sparked a bewildering amount of international intrigue, had found yet another role to play as a coveted prize in the greatest war the American videogame industry had ever known. Nintendo and Atari were both willing to use every resource at their disposal to ensure that Tetris belonged to them and them alone. All of the conspiratorial maneuvering that had taken place in Moscow the previous February and March was about to be put to the test. Did all of the rights to Tetris belong to Robert Stein to sub-license as he would, as Atari claimed, or did Stein possess only the computer-game and arcade rights, as Nintendo claimed? It must now be up to a court of law in the United States to decide.

(Sources: the books Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff and The Tetris Effect: The Game That Hypnotized the World by Dan Ackerman; the BBC television documentary From Russia with Love; Hardcore Gamer Vol.5 No.1; Nintendo Power of September/October 1989; The New York Times of February 3 1989 and March 9 1989.)