What makes a hero? Is a hero a cool cucumber who feels no fear, who charges into peril without giving a thought to life and limb? Or is a hero someone who quakes with terror but charges in anyway? I know which side I come down on. There are stories from the Second World War’s Battle of Britain of exhausted British pilots — Winston Churchill’s storied “few” — who were so petrified at the prospect of going up to meet the German attackers yet again that they literally had to be carried out to their planes and strapped into the cockpits, shaking, with tears streaming down their faces. Yet somehow, finally, they found the strength to enter the maelstrom again. If you ask me, courage isn’t the opposite of fear. Courage is rather feeling terrified but doing it anyway.

Edward “Mick” Mannock would never truly banish his fear, for fear, like addiction, is something one can never eradicate; one can only overcome it on an ad hoc, day-to-day basis. Yet Mannock would, like Churchill’s few, find a way to do his part despite his fear. This being a real rather than a Hollywood story, there is no single watershed moment we can point to and say that this marks the instant when he was transformed from a quivering greenhorn into a steel-eyed veteran. Instead there is a whole series of gradual steps. Mannock himself would come to regard May 9, 1917, when he returned to his aerodrome in such a state that his commanding officer took him off active duty for a short time, as being of some significance, marking as it did a crossroads where he faced a choice between accepting the shame of a transfer back to the home front or continuing to struggle with his raw terror in the air; he chose, of course, the latter. And it’s certainly tempting to mark June 7 on the calendar as well, the day that Mannock downed a German Albatros — his first official victory over an enemy airplane. (“My man gave me an easy mark,” he wrote in his diary. “I was only ten yards away from him — on top so I couldn’t miss! A beautifully coloured insect he was — red, blue, green, and yellow. I let him have 60 rounds at that range, so there wasn’t much left of him. I saw him going spinning and slipping down from 14,000 [feet]. Rough luck, but it’s war, and they’re Huns.”) Still, the process really was most of all a very gradual one. As Mannock grew less erratic in the air, and as he simply continued to live far beyond the normal life expectancy of a new scout pilot, his comrades in 40 Squadron slowly let go of their early judgments of him and accepted him into the life of the mess hall. And that acceptance in turn helped him to control his fear, a virtuous circle that transformed him in time into one of the squadron’s reliable old hands.

As Mannock was allowed to join in with the life of the squadron’s core, he joined them in the many coping mechanisms that soldiers at war develop. Rather amusingly, he was first encouraged to let his hair down by one B.W. Keymer, the squadron’s unusually earthy and thoroughly beloved chaplain, who understood and accepted that young men have needs of the flesh as well as the spirit. Keymer told Mannock that he should abandon his lingering resentments of class and politics to join the others on their drinking excursions into Saint-Omer. Meanwhile, through the example of his patronage, the good chaplain helped to convince others in the squadron to accept Mannock into their own good graces. In time, Mannock became one of the lives of the party at 40 Squadron, always willing to join in with whatever horseplay was afoot. One of the squadron’s favorite airborne pranks was astoundingly cruel really, but such are the ways of war: Mannock and his mates loved to swoop down out of the sun on unsuspecting friendly observation planes, just like they were Germans on the attack. From his diary:

Amused ourselves by dodging about the low clouds and frightening the engine out of sundry crawling “quirks” doing artillery work. Great sport. You come down vertically at approx. 160 mph on a poor unsuspecting observer and bank away to the right or left when almost cutting off his tail. You can almost hear him gasp.

One does have to wonder why no one ever got a nose full of machine-gun fire for his trouble…

But most of the squadron’s hijinks took place on the ground. Inevitably, alcohol became a key coping mechanism. Frederick Powell, one of Mannock’s squadron mates:

The centre of the squadron seemed to be in the bar. When you think of the tensions they lived through day to day — they would come in in the evening and ask about their best friend, “Where’s old George?” “Oh, he bought it this afternoon!” “Oh, heavens!” The gloom would come, the morale would die, and the reaction was immediate: “Well, come on, chaps, what are you going to have?” That was the sort of spirit that kept you going, and although people are against alcohol I think that it played a magnificent part in keeping up morale.

Coupled with the drink were other coping mechanisms of a more aggressive character. Games of rugby, sometimes played indoors right there in the mess hall, could get very rough indeed, yielding black eyes and broken fingers. Political discussions, in which Mannock was as strident as ever in advocating his socialist worldview, sometimes degenerated into brawls. Mannock and another flyer, a Second Lieutenant de Burgh, took to beating the sod out of one another as a matter of course on nearly a nightly basis. De Burgh:

Mannock was very keen on boxing, and as I had done a good deal [of it], we often used to blow off steam by having a set-to in the mess. It fact, it used to be a stock event, if the evening was livening up, for Mannock and me to have a round or two — and he nearly always said, “Let’s hit it out,” and we used to have a good slog at one another. I think, on the whole, that I used to get more than I gave, as he had the height of me and a slightly longer reach, but I had him at footwork.

The bad feelings engendered by the more violent nightly episodes seldom persisted beyond the alcoholic haze that did so much to create them. Living under almost unbelievable tension, knowing each successive flight had a good chance of being their last, the pilots were simply doing what they needed to to get through each successive day.

Mannock’s greatest fear was the same as that of many other pilots: to go down in what was called with typical forced jocularity a “flamer.” In an airplane made from a wooden frame covered with doped fabric, with a thin unarmored tank filled with many gallons of fuel, an aerial conflagration was never more than a single stray bullet away. Many pilots of stricken aircraft chose to jump to their deaths — parachutes were nonexistent prior to some German experiments very late in the war — rather than be burned alive with their planes. Mannock himself always carried a revolver up with him; “I’ll blow my brains out rather than go down roasting,” he said. To cope with this greatest fear, he indulged in elaborate black humor that made even many of his squadron mates, whose own humor was hardly of the most sensitive stripe, a bit queasy. The German aircraft that he shot down in flames he called “sizzlers” or “flamerinos.” He would describe their endings with a pyromaniac’s glee, finishing on a note of near-hysteria, whereupon he might turn to one of his comrades and suddenly burst out, in a jarringly high and strangled voice, “That’s what will happen to you on the next patrol, my lad.” The squadron would, remembered one pilot, dutifully “roar with laughter,” but it was uncomfortable laughter, its tone all wrong. “He is getting obsessed with this form of death,” thought one of them. “It is getting on his nerves.”

For all that Mannock loved to loudly and proudly proclaim his hatred of Germans, the killing he did in the air quite clearly affected him as much as did his constant fear for his own life. This was the other side of the supposedly glorious, chivalrous war in the air. The folks on the home front who tallied up the latest victory counts and ranked the aces failed to understand that war is not sport but rather a brutal exercise in kill or be killed. On July 13, after scoring his fourth victory, over a German two-man observation plane — he killed the pilot, but the observer somehow survived the crash — Mannock ventured into the trenches on foot for the first time to inspect his handiwork. While his diary describes the event with typical terseness, it can’t entirely disguise the effect the experience had on him.

I hurried out at the first opportunity and found the observer being tended by the local M.O., and I gathered a few souvenirs, although the infantry had the first pick. The machine was completely smashed, and rather interesting also was the little black-and-tan terrier — dead — in the observer’s seat. I felt exactly like a murderer. The journey to the trenches was rather nauseating — dead men’s legs sticking through the sides with putties and boots still on — bits of bones and skulls with the hair peeling off, and tons of equipment and clothing lying about. This sort of thing, together with the strong graveyard stench and the dead and mangled body of the pilot (an N.C.O.), combined to upset me for a few days.

This earliest incarnation of aerial warfare was an unnervingly intimate affair; it was often possible to hear the screams of pilots and crew as they were burned alive. Mannock’s attitude toward the killing he engaged in was, like so many things about this complex man, contradictory, swinging between manic glee at the death of another of the hated Huns and the guilt of, as he himself expresses it in the diary passage above, committing murder. On September 4, he shot down another flamer, killing both the pilot and the observer; it marked his eleventh victory. “He went down in flames, pieces of wing and tail, etc., dropping away from the wreck,” he wrote in his diary. “It was a horrible sight and made me feel sick.” He ventured out to the trenches to try to locate this kill as well, an act that now seemed to be becoming a compulsion for him. This time, however, he failed in his quest to examine his gruesome handiwork — probably, one has to think, for the best. While other aces were somehow able to fool themselves into believing they were destroying only machines, not men, Mannock was unable to delude himself in this way. At some level he seemed to revel in the knowledge that he was a mass killer, even as the same knowledge rent his psyche daily.

Months after his eleventh kill, a plaintive message that had been dropped over the front reached him while on leave in London.

I lost my friend Fritz Frech. He fell between Vimy and Lieven. His respectable and unlucky parents beg you to give any news of his fate. Is he dead? At what place found he his last rest? Please to throw several letters that we may found one. Thank before.

His friend, K. L.

P.S. If it is possible, please a letter to the parents:

Mr. Frech

Königsberg

Pr. Vord Vorstadt 48/52

The Fritz Frech in question had been the observer in the plane Mannock had shot down and watched burn up on September 4. Mannock did indeed write to the parents, explaining that their son was dead but sparing them the full details of how he had met his end at their correspondent’s own hands. If only such small human mercies could outweigh the horrors of war.

Despite those ongoing horrors of war, things were, relatively speaking, looking up for Mannock as 1917 entered its second half. On July 19, in an event that surprised him as much as anyone, he was awarded the Military Cross for his “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty,” despite having yet to score his coveted fifth kill and thus win the designation of ace (he would not accomplish that feat until August 5). In truth, such awards were being handed out with rather shocking liberality as a morale-boosting hedge against the enormous casualties among the airmen, but Mannock was nevertheless duly proud of the honor. Shortly after, he was promoted to a patrol leader with 40 Squadron. In less than three months, he had gone from faceless cannon fodder to mistrusted shirker to respected veteran in the eyes of his squadron mates. Such was the war in the air, where lifetimes were often measured in days.

But even that ugliest of statistics was starting to look better. By the fall, the average lifespan of a new British scout pilot on the Western Front had extended from the mere days of Bloody April to a downright generous ten weeks. This welcome development could be credited to a number of causes. The Arras offensive had, like all of the offensives before it, long since petered out into stalemate, and the fighting in the air had grown slightly less intense as well as a result. British standards of flight training were also improving, with more attention paid to the crucial skill of aerial gunnery and with trainees finally being given a reasonable amount of time in the sorts of aircraft they would actually be flying into battle at the front.

Yet the biggest cause of the improving British fortunes of war was the arrival of two new aircraft that at last proved a match for the dreaded German Albatros scouts. The Sopwith Camel, destined to become the most iconic airplane of the entire war thanks largely to a certain cartoon dog, was indeed a dogfighter’s dream. Extraordinarily maneuverable, it could do things in the air that literally no other plane could do. But it was also notoriously tricky to fly; the torque from its rotary engine, combined with its deceptively heavy tail, killed dozens if not hundreds of green pilots, who inadvertently slammed a wing or the tail into the ground on takeoff or landing or threw the plane into a hopeless spin when practicing aerobatics. “It was always teetering on being out of control,” writes the military historian Peter Hart of the Camel — and that was a good thing, for “if the pilot barely knew what was happening how could his opponent?”

The other new British plane is less famous than the Sopwith Camel, but in reality played an even more important role in swaying the balance of power in the air. Certainly it was much better suited to a no-nonsense aerial tactician of the sort that Mannock was rapidly becoming. The Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a wasn’t the purist pilot’s plane that the Sopwith Camel was. It was heavier on the controls and a bit lumbering really; if the Camel could turn on a dime, the S.E.5a needed at least a quarter. On the other hand, it could fly faster than the Camel, could climb faster and higher, and could take more punishment. It was also as forgiving of new pilots as the Camel was dangerous, and offered a wonderfully stable platform for its potent armaments, which consisted of the traditional British Lewis machine gun mounted on the upper wing along with, at long last, a Vickers mounted on the cowl of the fuselage, synchronized to fire between the propeller blades. The two guns were operated by one trigger, and were angled to intersect on a sweet spot about 100 yards ahead — or the pilot could aim and fire the Lewis manually for, for instance, raking the underside of an enemy aircraft that had on him the crucial advantage of height. Mannock would wind up scoring 46 of his eventual 61 victories in an S.E.5a. It was ideally suited for his favored tactic of swooping down on a German formation at high speed, raking it with gunfire from medium range, then using the kinetic energy of the dive to zoom back up into the sun for another go if necessary.

Still, Mannock’s relationship with the S.E.5a started out decidedly rocky. When 40 Squadron received the new aircraft as replacements for their trusty old Nieuport 17s some weeks before Christmas, they found them still beset with teething problems. Their water-cooled piston engines — much more complex than the air-cooled rotaries found on the Nieuports — were chronically unreliable, and, more than two years after the Germans had perfected their machine-gun synchronizer technology, the British were still struggling with theirs; the cowl-mounted gun could shoot off the propeller if something went wrong, leading many pilots to refuse to use it at all when over enemy lines. Mannock ranted bitterly about the S.E.5a to any superior who would listen, demanding fruitlessly that 40 Squadron be given back their Nieuports. He would manage to score just one victory in an S.E.5a in this final stretch of his first tour at the front.

Nevertheless, when Mannock left 40 Squadron in January of 1918 he left as, in the words of fellow flier Gwilym Lewis, “the hero of the squadron,” with 16 official victories to his credit.

He came on to form having been older than most of us and a more mature man. He had given great, deep thought to the fighting and had re-orientated his mental attitudes, which was necessary for a top fighter pilot. He had got his confidence and he had thought out the way he was going to tackle things. He became a very good friend of mine, and I owed a lot to him that he was so friendly. I was unnecessarily reserved, and he liked to give people nicknames — he called me “Noisy”! He was a lot of fun.

As a pilot and a fighter, Mannock was the polar opposite of the impulsive Albert Ball, who despite having been killed in May of 1917 still remained Britain’s most famous ace by far. Loath though he doubtless would have been to acknowledge the similarity, the ace Mannock most resembled was none other than Manfred von Richthofen — the legendary Red Baron, the greatest of all the German aces and, indeed, the greatest of the entire war. Like Mannock, Richthofen devoted much effort to codifying a system of rules for aerial combat as a disciplined team effort, leaving to the romantics who celebrated his achievements all the stirring poetics about jousting “knights of the air.” It would be no great exaggeration to say that the serious study of aerial combat as a tactical discipline unto itself really begins with these two men. The axioms they developed were often amazingly similar. Mannock, for instance, had learned after one or two early misfortunes the importance of checking his weaponry over thoroughly before flying into battle, and pounded this theme home relentlessly with his charges after being given command of his own flight. Here is Richthofen on the same subject:

It is the pilot and not the ordnance officer or the mechanic who is responsible for the faultless performance of his guns. Machine-gun jams do not exist! If they do occur, it is the pilot whom I blame. The pilot should personally examine his ammunition and its loading into the belt to ensure that the length of each round is consistent with that of the others. He has to find time to do this during bad weather or in good weather at night. A machine gun that fires well is better than an engine that runs well.

Both men regarded “stunt pilots,” those who placed their faith in reflexes and fancy maneuvers rather than sound tactics, with near contempt. Richthofen said that he “paid considerably less attention to flying ability” than he did to tactics and gunnery: “I shot down my first twenty whilst flying itself caused me the greatest trouble.” Both men were thoroughgoing pragmatists, willing to engage in battle only when the odds in terms of numbers and position were in their favor, and willing to break off any engagement rather than bring undue risks upon themselves. Most of all, both men were great leaders and teachers. Already during his first tour, Mannock was noted for his patience with the new fliers who came under his charge; his own rocky first weeks with 40 Squadron gave him much empathy for these greenhorns’ plight. He would place them in relatively sheltered positions during their first flights and work to indoctrinate them into his teamwork-oriented, “no individual heroes” approach. Similarly, Richthofen could at times sound more like a fussy schoolmarm than a dashing fighter ace:

It is important and instructive that a discussion be held immediately after each Jagdgeschwader flight. During this everything should be discussed from takeoff to landing and whatever had happened during the flight should be talked through. Questions from individuals can be most useful in explaining things.

If it’s difficult to reconcile Mannock the patient teacher and cerebral tactician with the hooligan who liked to beat people bloody in a bar every night, count it up as yet one more contradictory aspect of this hopelessly contradictory man.

By this time, seasoning a new squadron with two or three combat veterans had become standard practice in the Royal Flying Corps. Thus, after some weeks of much-deserved leave, Mannock was sent to join the brand new 74 Squadron in England. The commander of the squadron, a tough Kiwi named Keith Caldwell, deferred greatly to him, treating him almost as his equal in the chain of command. It was a golden opportunity for Mannock to indoctrinate a mass of unformed clay into his theories of air combat. This he proceeded to do over the several weeks prior to his return to the front with his new squadron, driving home easily remembered rules of thumb like “always above; seldom on the same level; never underneath.” He wasn’t unwilling to use occasional tough love on his skittish charges; a pilot who broke formation might be terrified by a burst of live machine-gun fire, deployed by Mannock to get his attention and force him back into position.

Among the fliers he instructed was one Ira Jones, who would go on to write the most famous biography of Mannock, albeit one so drowning in Jones’s unabashed hero worship that it’s sometimes more interesting as a psychological study of its author than it is for its ostensible subject. Here, for instance, is Jones’s breathless description of his first impression of his squadron’s new flight leader:

His tall, lean figure; his weather-beaten face with its deep-set Celtic blue eyes; his modesty in dress and manner appealed to me, and immediately, like all the other pupils, I came under his spell. He had a dominating personality, which radiated itself on all those around. Whatever he said or did compelled attention. It was obvious that he was a born leader of men.

Aided by Caldwell’s strict discipline and Mannock’s tactical mastery, along with the latest iteration of the S.E.5a, from which the Royal Aircraft Factory had finally shaken out the bugs, 74 Squadron would be a remarkably successful combat unit, losing very few pilots in proportion to the kills they scored against the Germans.

They would need to be. The front to which Mannock returned with his new squadron on March 30, 1918, was a very different place from the one he had left, thanks to two titanic political events of the previous year. One had been the declaration of war by the United States upon Germany and its allies; the other had been the Russian Revolution, following which the government of the new Russian Soviet Republic had signed peace terms with Germany. The army of the United States, still a sleeping giant on the world stage just waking up to its own potential, had been very nearly nonexistent prior to the declaration of war. It would take the Americans more than a year to train, equip, and ship enough soldiers across the Atlantic to make a significant difference in Western Europe. Once that happened, however, the jig would be up; Germany couldn’t hope to continue to hold the front against the combined armies of France, Britain, and the United States. The German commanders believed, logically enough, that they stood just one chance: to shift all of their forces from the old Eastern Front to the Western and throw absolutely everything they had against the Allies during that spring of 1918, in the hope of breaking through and sweeping to the coast in these last few precious weeks before American forces began to arrive en masse. This, then, was the desperate battleground that 74 Squadron flew into.

When the squadron flew into action for the first time on April 12, the young Ira Jones, much like the Mannock of almost exactly one year earlier, performed poorly and returned to the aerodrome in a very bad way.

The feeling of safety produced an amazing reaction of fear, the intensity of which was terrific. Suddenly I experienced a physical and moral depression which produced cowardice. I suddenly felt I was totally unsuited to air fighting and that I would never be persuaded to fly over the lines again. For quite five minutes I shivered and shook.

Departing markedly from the treatment his old squadron mates had meted out to him in the same situation, Mannock quietly pulled Jones aside and told him about his own early struggles, sharing some tips on how he had learned to manage his fear and thus how Jones might as well. Jones’s ardent lifelong hero-worship of Mannock seems to date from this exchange — and understandably so. Motivated perhaps as much by his horror of disappointing his hero as by anything else, Jones soon rounded into one of the squadron’s steady hands.

Jones’s story was hardly unique. Mannock was brilliant at motivating and instilling confidence in new fliers in general. A favorite technique was to “break the duck” of a hesitant newcomer by taking out the gunner of a German observation craft himself, then signaling the greenhorn to finish the job and thus come away with his first victory. Doing so wasn’t quite the sacrifice that it might first appear; the rules for scoring the war in the air stipulated that every pilot who helped to bring down an enemy airplane received credit for that victory, meaning Mannock could feel free to spread the wealth around without sacrificing his own tally. Nevertheless, it was a generous act, even as it was also a rather macabre act — but, again, such are the ways of war.

Caldwell and Mannock molded their squadron into a disciplined fighting unit the equal of the Red Baron’s dreaded “Flying Circus.” Jones:

He [Mannock] not only mystified and surprised the enemy, but also the formations he led. Once over the lines, he would commence flying in a never-ending series of zigzags, never straight for more than a few seconds. Was it not by flying straight for long periods that formation leaders were caught napping?

Suddenly his machine would rock violently, a signal that he was about to attack. But where was the enemy? His companions could not see them, although he was pointing in their direction. Another signal and his SE would dive to the attack. A quick half-roll, and there beneath him would be the enemy formation flying serenely along, the enemy leader with his eyes no doubt glued to the west. The result [was] a complete surprise attack.

Mannock would take the leader if possible in order to give his pilots coming down behind him a better chance of an easy shot at someone before the formation split up and the dogfight began. Having commenced the fight with the tactical advantage of height in his favour, Mannock would adopt dive-and-zoom tactics in order to retain the initiative.

Thanks not least to Mannock, 74 Squadron was one of the happiest on the front, even if that happiness was always tinged with the usual unnatural mania, always shadowed by the stress and terror it worked so diligently to cover up. Jones again:

Mannock was always full of pranks. His favourite one was to enter a comrade’s hut in the early hours of the morning after returning from a “night out”. He would enter, usually accompanied by Caldwell, who would be carrying a jug of water. Once inside, Mannock would pretend that he had wined and dined too well, and would make gurgling noises as if he was going to be sick. As each retching noise was made, Caldwell would splash an appropriate amount of water on the wooden floor. The poor lad asleep would suddenly wake up and jump out of bed to the accompaniment of roars of laughter as his legs would be splashed with the remaining water.

Despite the emphasis on teamwork in the air, Mannock’s personal victory count soared during this his second tour of duty — as incontrovertible a proof as any of just how effective his tactics really were. In barely two months, he increased his tally from 16 to 52, an astonishing run that often saw him shooting down multiple German aircraft on a single day or even a single patrol. His pace during this period was unequaled during any similar stretch of time by any other ace of the war. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order on May 24, then the same medal again just two weeks later after destroying eight German aircraft in five days.

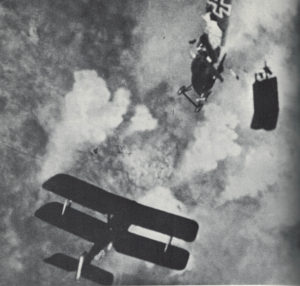

Given the doctrine he preached to his pilots, one might think that Mannock would have been uninterested in his personal tally and the personal glory that went with it. But, once again, to do so would be to underestimate the complexity of this endlessly complex and contradictory man. On April 21, 1918, shortly after Mannock’s return to the front, a gunner on the ground shot down Manfred von Richthofen largely by luck, firing a bullet toward his Fokker Triplane that pierced his heart and lungs, killing him almost instantly. When the pilots in 74 Squadron’s mess hall that night proposed a toast to their fallen nemesis, Mannock merely scowled and said, “I hope he roasted the whole way down!” He now had a static target to strive for: Richthofen had tallied 80 victories. First, however, he would need to oust his old friend and rival James McCudden, currently back in England with 57 victories to his name. Ominously, he wrote home that he intended to beat all the other aces’ tallies or to “die in the attempt.” Did he, a working-class man, want so desperately to unseat the Red Baron — who, as evidenced by his nickname, was a member of the Prussian aristocracy — as a comeuppance to the class system that had so often used him so badly? We can only speculate.

The British buried Richthofen with full military honors, and even dropped pictures of his grave behind German lines. Mannock, needless to say, wasn’t susceptible to such sentimentality.

By June, the final frenzied German attack on the ground had largely exhausted itself. It had been a near thing on multiple occasions, with the Allied lines buckling at times far more than they had in all the previous years of war. Still, the Germans had never quite managed to achieve the full-on breach for which they had died in so many thousands. Now, with fresh American troops at last beginning to pour into France to take up the fray against the battered German armies, the war could only end one way; it was merely a question of when. For the first time, the soldiers and aviators on the front could realistically look forward to the prospect of peace in the near future.

And yet Mannock, still the picture of leadership and camaraderie on one level, was falling apart on another. Increasingly obsessed with his victory count even as the terror and guilt he constantly felt threatened always to master him, he was caught in a downward spiral from which he didn’t know how to extricate himself. His obsession with going down in a “sizzler” became more pronounced than ever; even the starry-eyed Ira Jones had to admit that his hero was “getting very peculiar about the whole business.” He took to asking the other pilots, “Are you ready to die for your country today? Will you have it in flames or in pieces?” Even more disturbingly, he began to abandon some of his own tactical dicta. On June 16, for example, he initiated an attack on a German formation that outnumbered his flight by three to one, a clear violation of everything he had always taught his charges; he shot down two planes that day, but the rest of his pilots felt lucky just to escape with their lives. Premonitions of death began to creep more and more into his correspondence. He wrote to his old friend and mentor Jim Eyles:

Things are getting a bit intense just lately and I don’t quite know how long my nerves will last out. I am rather old now, as airmen go, for air fighting. Still, one hopes for the best. These times are so horrible that occasionally I feel that life is not worth hanging on to myself, but “hope springs eternal in the human breast”.

On June 21, Mannock was informed that he was to assume command of 85 Squadron, another unit at the front. He would now be given the rank of Major, a remarkable ascent for a working-class man less than three years removed from the Territorial Forces. His new squadron was another very effective unit; it had lately been commanded by Billy Bishop, a Canadian who with 72 victories to his credit would go down into history as the ace of aces of all the British Commonwealth airmen. That said, Bishop’s actual tally may well have been much lower. There is reason to believe that, eager to inspire the fighting men of the Commonwealth, British commanders may have deliberately inflated his victory count; some historians are willing to credit him with as few as 27 real, confirmable victories. Regardless, Bishop was considered to be of huge symbolic importance. For this reason, he had been withdrawn from active duty; witnessing what a blow to German public morale the death of the Red Baron had been, there was concern about the potential fallout if Bishop should be killed in action. But about Mannock, who despite his achievements remained peculiarly obscure among all but the airmen actually at the front, there was no similar concern. Thus the expendable Mannock was to inherit Commonwealth hero Bishop’s command.

Canadian Billy Bishop, the British Commonwealth’s alleged ace of aces, who probably wasn’t the conscious fraud some have claimed he was but who may very well have benefited from a less than rigorous kill-verification process in light of his immense propaganda value.

Before he took over 85 Squadron, Mannock was granted the small mercy of two weeks’ leave back in England. He repaired to the town of Wellingborough, where he had enjoyed the most peaceful three years of his life living under the roof of Jim Eyles — a stretch that must truly have felt like another lifetime to him by this point. Eyles was as shocked by the version of “Pat” Mannock who knocked on his door on this summer day in 1918 as he had been by the one who had returned sick and malnourished from a Turkish prison three years before. To judge by Eyles’s description, Mannock may have been in the throes of a full-blown nervous breakdown by this point; his hands and body trembled constantly. One day Eyles came upon him unaware, standing in the house’s cozy little kitchen:

He cried uncontrollably, muttering something that I could not make out. His face, when he lifted it, was a terrible sight. Saliva and tears were running down his face; he couldn’t stop it. His collar and shirt front were soaked through. He smiled weakly at me when he saw me watching and tried to make light of it. He would not talk about it at all.

Eyles would later say that, although they didn’t express it in words, the two old friends shared a mutual understanding that this would be the last time they would be together. There was “something very final about it” when the two shook hands on the last morning of Mannock’s leave and Eyles’s old companion in socialism and cricket set off down the garden path, just as he had done hundreds of times before while working as a rigger for the National Telephone Company right there in Wellingborough. But, alas, the job to which he was returning today was a far more deadly business. Hadn’t he done enough for his country? Apparently not. He was in a state of complete psychic collapse, yet the powers that were in England still didn’t respect him enough that anybody had bothered to notice. Again — for the last time this time — Major Edward “Eddie/Paddy/Pat/Jerry/Murphy/Mickey/Mick” Corringham Mannock was going to war.

(Sources: The same as the first article in this series.)