Because the CD-ROM version of The Manhole sold in relatively small numbers in comparison to the original floppy version, the late Russell Lieblich’s surprisingly varied original soundtrack is too seldom heard today. So, in the best tradition of multimedia computing (still a very new and sexy idea in the time about which I’m writing), feel free to listen while you read.

Were HyperCard “merely” the essential bridge between Ted Nelson’s Xanadu fantasy and the modern World Wide Web, it would stand as one of the most important pieces of software of the 1980s. But, improbably, HyperCard was even more than that. It’s easy to get so dazzled by its early implementation of hypertext that one loses track entirely of the other part of Bill Atkinson’s vision for the environment. True to the Macintosh, “the computer for the rest of us,” Atkinson designed HyperCard as a sort of computerized erector set for everyday users who might not care a whit about hypertext for its own sake. With HyperCard, he hoped, “a whole new body of people who have creative ideas but aren’t programmers will be able to express their ideas or expertise in certain subjects.”

He made good on that goal. An incredibly diverse group of people worked with HyperCard, a group in which traditional hackers were very much the minority. Danny Goodman, the man who became known as the world’s foremost authority on HyperCard programming, was actually a journalist whose earlier experiences with programming had been limited to a few dabblings in BASIC. In my earlier article about hypertext and HyperCard, I wrote how “a professor of music converted his entire Music Appreciation 101 course into a stack.” Well, readers, I meant that literally. He did it himself. Industry analyst and HyperCard zealot Jan Lewis:

You can do things with it [HyperCard] immediately. And you can do sexy things: graphics, animation, sound. You can do it without knowing how to program. You get immediate feedback; you can make a change and see or hear it immediately. And as you go up on the learning curve — let’s say you learn how to use HyperTalk [the bundled scripting language] — again, you can make changes easily and simply and get immediate feedback. It just feels good. It’s fun!

And yet HyperCard most definitely wasn’t a toy. People could and did make great, innovative, commercial-quality software using it. Nowhere is the power of HyperCard — a cultural as well as a technical power — illustrated more plainly than in the early careers of Rand and Robyn Miller.

Rand and Robyn had a very unusual upbringing. The first and third of the four sons of a wandering non-denominational preacher, they spent their childhoods moving wherever their father’s calling took him: from Dallas to Albuquerque, from Hawaii to Haiti to Spokane. They were a classic pairing of left brain and right brain. Rand had taken to computers from the instant he was introduced to them via a big time-shared system whilst still in junior high, and had made programming them into his career. By 1987, the year HyperCard dropped, he was to all appearances settled in life: 28 years old, married with children, living in a small town in East Texas, working for a bank as a programmer, and nurturing a love for the Apple Macintosh (he’d purchased his first Mac within days of the machine’s release back in 1984). He liked to read books on science. His brother Robyn, seven years his junior, was still trying to figure out what to do with his life. He was attending the University of Washington in somewhat desultory fashion as an alleged anthropology major, but devoted most of his energy to drawing pictures and playing the guitar. He liked to read adventure novels.

HyperCard struck Rand Miller, as it did so many, with all the force of a revelation. While he was an accomplished enough programmer to make a living at it, he wasn’t one who particularly enjoyed the detail work that went with the trade. “There are a lot of people who love digging down into the esoterics of compilers and C++, getting down and dirty with typed variables and all that stuff,” he says. “I wanted a quick return on investment. I just wanted to get things done.” HyperCard offered the chance to “get things done” dramatically faster and more easily than any programming environment he had ever seen. He became an immediate convert.

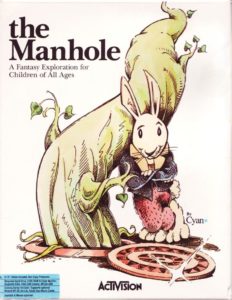

With two small girls of his own, Rand felt keenly the lack of quality children’s software for the Macintosh. He hit upon the idea of making a sort of interactive storybook using HyperCard, a very natural application for a hypertext tool. Lacking the artistic talent to make a go of the pictures, he thought of his little brother Robyn. The two men, so far apart in years and geography and living such different lives, weren’t really all that close. Nevertheless, Rand had a premonition that Robyn would be the perfect partner for his interactive storybook.

But Robyn, who had never owned a computer and had never had any interest in doing so, wasn’t immediately enticed by the idea of becoming a software developer. Getting him just to consider the idea took quite a number of letters and phone calls. At last, however, Robyn made his way down to the Macintosh his parents kept in the basement of the family home in Spokane and loaded up the copy of HyperCard his brother had sent him. There, like so many others, he was seduced by Bill Atkinson’s creation. He started playing around, just to see what he could make. What he made right away became something very different from the interactive storybook, complete with text and metaphorical pages, that Rand had envisioned. Robyn:

I started drawing this picture of a manhole — I don’t even know why. You clicked on it and the manhole cover would slide off. Then I made an animation of a vine growing out. The vine was huge, “Jack and the Beanstalk”-style. And then I didn’t want to turn the page. I wanted to be able to navigate up the vine, or go down into the manhole. I started creating a navigable world by using the very simple tools [of HyperCard]. I created this place. I improvised my way through this world, creating one thing after another. Pretty soon I was creating little canals, and a forest with stars. I was inventing it as I went. And that’s how the world was born.

For his part, Rand had no problem accepting the change in approach:

Immediately you are enticed to explore instead of turning the page. Nobody sees a hole in the ground leading downward and a vine growing upward and in the distance a fire hydrant that says, “Touch me,” and wants to turn the page. You want to see what those things are. Instead of drawing the next page [when the player clicked a hotspot], he [Robyn] drew a picture that was closer — down in the manhole or above on the vine. It was kind of a stream of consciousness, but it became a place instead of a book. He started sending me these images, and I started connecting them, trying to make them work, make them interactive.

In this fashion, they built the world of The Manhole together: Robyn pulling its elements from the flotsam and jetsam of his consciousness and drawing them on the screen, Rand binding it all together into a contiguous place, and adding sound effects and voice snippets here and there. If they had tried to make a real game of the thing, with puzzles and goals, such a non-designed approach to design would likely have gone badly wrong in a hurry.

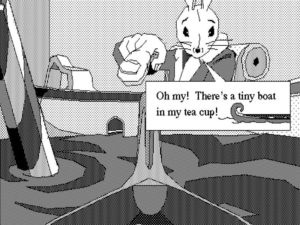

Luckily, puzzles and goals were never the point of The Manhole. It was intended always as just an endlessly interesting space to explore. As such, it would prove capable of captivating children and the proverbial young at heart for hours, full as it was of secrets and Easter eggs hidden in the craziest of places. One can play with The Manhole on and off for literally years, and still continue to stumble upon the occasional new thing. Interactions are often unexpected, and unexpectedly delightful. Hop in a rowboat to take a little ride and you might emerge in a rabbit’s teacup. Start watching a dragon’s television — Why does a dragon have a television? Who knows! — and you can teleport yourself into the image shown on the screen to emerge at the top of the world. Search long enough, and you might just discover a working piano you can actually play. The spirit of the thing is perhaps best conveyed by the five books you find inside the friendly rabbit’s home: Alice in Wonderland; The Wind in the Willows; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; Winnie the Pooh; and Metaphors of Intercultural Philosophy (“This book isn’t about anything!”). Like all of those books excepting, presumably, the last, The Manhole is pretty wonderful, a perfect blend of sweet cuteness and tart whimsy.

With no contacts whatsoever within the Macintosh software industry, the brothers decided to publish The Manhole themselves via a tiny advertisement in the back of Macworld magazine, taken out under the auspices of Prolog, a consulting company Rand had founded as a moonlighting venture some time before. They rented a tiny booth to show The Manhole publicly for the first time at the Hyper Expo in San Francisco in June of 1988. (Yes, HyperCard mania had gotten so intense that there were entire trade shows dedicated just to it.) There they were delighted to receive a visit from none other than HyperCard’s creator Bill Atkinson, with his daughter Laura in tow; not yet five years old, she had no trouble navigating through their little world. Incredibly, Robyn had never even heard the word “hypertext” prior to the show, had no idea about the decades of theory that underpinned the program he had used, savant-like, to create The Manhole. When he met a band of Ted Nelson’s disgruntled Xanadu disciples on the show floor, come to crash the HyperCard party, he had no idea what they were on about.

But the brothers’ most important Hyper Expo encounter was a meeting with Richard Lehrberg, Vice President for Product Development at Mediagenic, [1]Activision was renamed Mediagenic at almost the very instant that Lehrberg first met the Miller brothers. When the name change was greeted with universal derision, Activision/Mediagenic CEO Bruce Davis quickly began backpedaling on his hasty decision. The Manhole, for instance, was released by Mediagenic under their “Activision” label — which was odd because under the new ordering said label was supposed to be reserved for games, and The Manhole was considered children’s software, not a traditional game. I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article as the least confusing way to address a confusing situation. who took a copy of The Manhole away with him for evaluation. Lehrberg showed it to William Volk, whom he had just hired away from the small Macintosh and Amiga publisher Aegis to become Mediagenic’s head of technology; he described it to Volk unenthusiastically as “this little HyperCard thing” done by “two guys in Texas.” Volk was much more impressed. He was immediately intrigued by one aspect of The Manhole in particular: the way that it used no buttons or conventional user-interface elements at all. Instead, the pictures themselves were the interface; you could just click where you would and see what happened. It was perhaps a product of Robyn Miller’s sheer naïveté as much as anything else; seasoned computer people, so used to conventional interface paradigms, just didn’t think like that. But regardless of where it came from, Volk thought it was genius, a breaking down of a wall that had heretofore always separated the user from the virtual world. Volk:

The Miller brothers had come up with what I call the invisible interface. They had gotten rid of the idea of navigation buttons, which was what everyone was doing: go forward, go backward, turn right, turn left. They had made the scenes themselves the interface. You’re looking at a fire hydrant. You click on the fire hydrant; the fire hydrant sprays water. You click on the fire hydrant again; you zoom in to the fire hydrant, and there’s a little door on the fire hydrant. That was completely new.

Of course, other games did have you clicking “into” their world to make things happen; the point-and-click adventure genre was evolving rapidly during this period to replace the older parser-driven adventure games. But even games like Déjà Vu and Maniac Mansion, brilliantly innovative though they were, still surrounded their windows into their worlds with a clutter of “verb” buttons, legacies of the genre’s parser-driven roots. The Manhole, however, presented the player with nothing but its world. What with its defiantly non-Euclidean — not to say nonsensical — representation of space and its lack of goals and puzzles, The Manhole wasn’t a conventional adventure game by any stretch. Nevertheless, it pointed the way to what the genre would become, not least in the later works of the Miller brothers themselves.

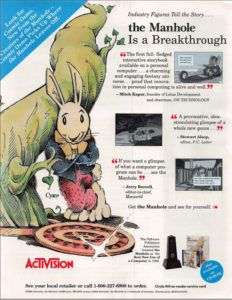

Much of Volk’s working life for the next two years would be spent on The Manhole, by the end of which period he would quite possibly be more familiar with its many nooks and crannies than its own creators were. He became The Manhole‘s champion inside Mediagenic, convincing his colleagues to publish it, thereby bringing it to a far wider audience than the Miller brothers could ever have reached on their own. Released by Mediagenic under their Activision imprint, it became a hit by the modest standards of the Macintosh consumer-software market. Macworld magazine named The Manhole the winner of their “Wild Card” category in a feature article on the best HyperCard stacks, while the Software Publishers Association gave it an “Excellence in Software” award for “Best New Use of a Computer.”

Well aware that The Manhole was collecting a certain chic cachet to itself, Mediagenic/Activision didn’t hesitate to play that angle up in their advertising.

Had that been left to be that, The Manhole would remain historically interesting as both a delightful little curiosity of its era and as the starting point of the hugely significant game-development careers of the Miller brothers. Yet there’s more to the story.

William Volk, frustrated with the endless delays of CD-I and the state of paralysis the entire industry was in when it came to the idea of publishing entertainment software on CD, had been looking for some time for a way to break the logjam. It was Stewart Alsop, an influential tech journalist, who first suggested to Volk that the answer to his dilemma was already part of Mediagenic’s catalog — that The Manhole would be perfect for CD-ROM. Volk was just the person to see such a project through, having already experimented extensively with CD-ROM and CD-I as part of Aegis as well as Mediagenic. With the permission of the Miller brothers, he recruited Russell Lieblich, Mediagenic’s longstanding guru in all things music- and sound-related, to compose and perform a soundtrack for The Manhole which would play from the CD as the player explored.

An important difference separates the way the music worked in the CD-ROM version of The Manhole from the way it worked in virtually all computer games to appear before it. The occasional brief digitized snippet aside, music in computer games had always been generated on the computer, whether by sound chips like the Commodore 64’s famous SID or entire sound boards like the top-of-its-class Roland MT-32 (we shall endeavor to forget the horrid beeps and squawks that issued from the IBM PC and Apple II’s native sound hardware). But The Manhole‘s music, while having been originally generated entirely or almost entirely on computers in Lieblich’s studio, was then recorded onto CD for digital playback, just like a song on a music CD. This method, made possible only by evolving computer sound hardware and, most importantly, by the huge storage capacity of a CD-ROM, would in the years to come slowly become simply the way that computer-game music was done. Today many big-budget titles hire entire orchestras to record soundtracks as elaborate and ambitious as the ones found in big Hollywood feature films, whilst also including digitized recordings of voices, squealing tires, explosions, and all the inevitable rest. In fact, surprisingly little of the sound present in most modern games is synthesized sound, a situation that has long since relegated elaborate setups like the Roland MT-32 to the status of white elephants; just pipe your digitized recording through a digital-to-analog converter and be done with it already.

As the very first title to go all digitized all the time, The Manhole didn’t have a particularly easy time of it; getting the music to play without breaking up or stuttering as the player explored presented a huge challenge on the Macintosh, a machine whose minimalist design burdened the CPU with all of the work of sound generation. However, Volk and his colleagues got it going at last. Published in the spring of 1989, the CD-ROM version of The Manhole marked a major landmark in the history of computing, the first American game — or, at least, software toy (another big buzzword of the age, as it happens) — to be released on CD-ROM. [2]The first CD-based software to reach European consumers says worlds about the differences that persisted between American and European computing, and about the sheer can-do ingenuity that so often allowed British programmers in particular to squeeze every last ounce of potential out of hardware that was usually significantly inferior to that enjoyed by their American counterparts. Codemasters, a budget software house based in Warwickshire, came up with a very unique shovelware package for the 1989 Christmas season. They transferred thirty old games from cassette to a conventional audio CD, which they then sold along with a special cable to run the output from an ordinary music-CD player into a Sinclair or Amstrad home computer. “Here’s your CD-ROM,” they said. “Have a ball.” By all accounts, Codemasters’s self-proclaimed “CD revolution,” kind of hilarious and kind of brilliant, did quite well for them. When it came to doing more with less in computing, you never could beat the Brits. Volk, infuriated with Philips for the chaos and confusion CD-I’s endless delays had wrought in an industry he believed was crying out for the limitless vistas of optical storage, sent them a copy of The Manhole along with a curt note: “See! We did it! We’re tired of waiting!”

And they weren’t done yet. Having gotten The Manhole working on CD-ROM on the Macintosh, Volk and his colleagues at Mediagenic next tackled the daunting task of porting it to the most popular platform for consumer software, MS-DOS — a platform without HyperCard. To address this lack, Mediagenic developed a custom engine for CD-ROM titles on MS-DOS, dubbing it the Multimedia Applications Development Environment, or MADE. [3]MADE’s scripting language was to some extent based on AdvSys, a language for amateur text-adventure creation that never quite took off like the contemporaneous AGT. Mediagenic’s in-house team of artists redrew Robyn Miller’s original black-and-white illustrations in color, and The Manhole on CD-ROM for MS-DOS shipped in 1990.

In my opinion, The Manhole lost some of its unique charm when it was colorized for MS-DOS. The VGA graphics, impressive in their day, look just a bit garish and overdone today in comparison to the classic pen-and-ink style of the original.

The Manhole, idiosyncratic piece of artsy children’s software that it was, could hardly have been expected to break the industry’s optical logjam all on its own. Its CD-ROM incarnation, for that matter, wasn’t all that hugely different from the floppy version. In the end, one has to acknowledge that The Manhole on CD-ROM was little more than the floppy version with a soundtrack playing in the background — a nice addition certainly, but perhaps not quite the transformative experience which all of the rhetoric surrounding CD-ROM’s potential might have led one to expect. It would take another few excruciating years for a CD-ROM drive to become a must-have accessory for everyday American computers. Yet every revolution has to start somewhere, and William Volk deserves his full measure of credit for doing what he could to push this one forward in the only way that could ultimately matter: by stepping up and delivering a real, tangible product at long last. As Steve Jobs used to say, “Real artists ship.”

The importance of The Manhole, existing as it does right there at the locus of so much that was new and important in computing in the late 1980s, can be read in so many ways that there’s always a danger of losing some of them in the shuffle. But it should never be forgotten whilst trying to sort through the tangle that this astonishingly creative little world was principally designed by someone who had barely touched a computer in his life before he sat down with HyperCard. That he wound up with something so fascinating is a huge tribute not just to Robyn Miller and his enabling brother Rand, but also to Bill Atkinson’s HyperCard itself. Apple has long since abandoned HyperCard, and we enjoy no precise equivalent to it today. Indeed, its vision of intuitive, non-pretentious, fun programming is one that we’re in danger of losing altogether. Being one who loves the computer most of all as the most exciting tool for creation ever invented, I can’t help but see that as a horrible shame.

The Miller brothers had, as most of you reading this probably know, a far longer future in front of them than HyperCard would get to enjoy. Already well before 1988 was through they had rechristened themselves Cyan Productions, a name that felt much more appropriate for a creative development house than the businesslike Prolog. As Cyan, they made two more pieces of children’s software, Cosmic Osmo and the Worlds Beyond the Makerei and Spelunx and the Caves of Mr. Seudo. Both were once again made using HyperCard, and both were very much made in the spirit of The Manhole. And like The Manhole both were published on CD-ROM as well as floppy disk; the Miller brothers, having learned much from Mediagenic’s process of moving their first title to CD-ROM, handled the CD-ROM as well as the floppy versions themselves when it came to these later efforts. Opinions are somewhat divided on whether the two later Cyan children’s titles fully recapture the magic that has led so many adults and children alike over the years to spend so much time plumbing the depths of The Manhole. None, however, can argue with the significance of what came next, the Miller brothers’ graduation to games for adults — and, as it happens, another huge milestone in the slow-motion CD-ROM revolution. But that story, like so many others, is one that we’ll have to tell at another time.

(Sources: Amstrad Action of January 1990; Macworld of July 1988, October 1988, November 1988, March 1989, April 1989, and December 1989; Wired of August 1994 and October 1999; The New York Times of November 28 1989. Also the books Myst and Riven: The World of the D’ni by Mark J.P. Wolf and Prima’s Official Strategy Guide: Myst by Rick Barba and Rusel DeMaria, and the Computer Chronicles television episodes entitled “HyperCard,” “MacWorld Special 1988,” “HyperCard Update,” and “Hypertext.” Online sources include Robyn Miller’s Myst postmortem from the 2013 Game Developer’s Conference; Richard Moss’s Ludiphilia podcast; a blog post by Robyn Miller. Finally, my huge thanks to William Volk for sharing his memories and impressions with me in an interview and for sending me an original copy of The Manhole on CD-ROM for my research.

The original floppy-disk-based version of The Manhole can be played online at archive.org. The Manhole: Masterpiece Edition, a remake supervised by the Miller brothers in 1994 which sports much-improved graphics and sound, is available for purchase on Steam.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Activision was renamed Mediagenic at almost the very instant that Lehrberg first met the Miller brothers. When the name change was greeted with universal derision, Activision/Mediagenic CEO Bruce Davis quickly began backpedaling on his hasty decision. The Manhole, for instance, was released by Mediagenic under their “Activision” label — which was odd because under the new ordering said label was supposed to be reserved for games, and The Manhole was considered children’s software, not a traditional game. I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article as the least confusing way to address a confusing situation. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The first CD-based software to reach European consumers says worlds about the differences that persisted between American and European computing, and about the sheer can-do ingenuity that so often allowed British programmers in particular to squeeze every last ounce of potential out of hardware that was usually significantly inferior to that enjoyed by their American counterparts. Codemasters, a budget software house based in Warwickshire, came up with a very unique shovelware package for the 1989 Christmas season. They transferred thirty old games from cassette to a conventional audio CD, which they then sold along with a special cable to run the output from an ordinary music-CD player into a Sinclair or Amstrad home computer. “Here’s your CD-ROM,” they said. “Have a ball.” By all accounts, Codemasters’s self-proclaimed “CD revolution,” kind of hilarious and kind of brilliant, did quite well for them. When it came to doing more with less in computing, you never could beat the Brits. |

| ↑3 | MADE’s scripting language was to some extent based on AdvSys, a language for amateur text-adventure creation that never quite took off like the contemporaneous AGT. |