Bill Williams’s Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon marked the end of the first era of Cinemaware’s existence. Bob Jacob’s original vision for his company had been as a sort of coordinator and advisory board, helping independent developers craft games inspired by the movies — an approach to game development as conceptually original as he hoped the games themselves would prove. The finished results from his initial stable of four such development contracts, however, quickly disabused him of the scheme. The mishmash of styles, platforms, and technical approaches among his developers resulted in games that shared little in common either visually or philosophically — and that was without even considering the near-disaster that had resulted from Sculptured Software’s mishandling of the most ambitious of the four projects, Defender of the Crown. The rescue operation that Cinemaware had been forced to mount to get that game out in time for the Christmas of 1986, involving as it did the taking over of day-to-day management of the project, had proved the old adage that if you want something done properly you just have to do it yourself. By the time that Sinbad, the last of those original contracts by far to reach fruition, trickled out in mid-1987, Jacob was already well along in the task of remaking Cinemaware into a full-fledged development house. This mid-course correction necessitated a dramatic expansion of the operation in terms of assets, office space, and personnel — in other words, the addition of all of the headaches he had hoped to avoid via his original vision. But needs must, right?

Jacob now stopped hedging his bets among the combatants in the 68000 Wars. Cinemaware the full-fledged development house would be built around the Amiga, becoming in the process the American game developer most closely identified with the platform during its best years in its homeland. Given Defender of the Crown‘s huge success, it was natural for Cinemaware to turn to that game among their early titles as their technical and artistic model for the future. Indeed, Cinemaware’s in-house tools were built on the broad base of a reusable “game-playing engine” for the Amiga that R.J. Mical had started developing in the process of making that game. Each Cinemaware game would be developed and released first on the Amiga, with the Amiga graphics and sound then degraded as artfully as possible to the variety of other platforms the company continued to support. Cinemaware’s programmers developed quite a variety of tools to automate this process as much as possible, yielding, if not quite a true cross-platform game engine, a standard approach with many of the benefits of one. It gave Cinemaware what seemed the best of both worlds: the prestige of being the premier developer for the most audiovisually impressive platform of its day combined with the ability to still sell games on the other, less capable but more numerous machines whose owners lusted after a taste of the Amiga’s magic.

Thanks to Defender of the Crown‘s huge success on the Amiga, Jacob had some time and a solid incoming revenue stream to use in executing the transition. He would need it, especially as both artist Jim Sachs and programmer R.J. Mical, the two masterminds who had together brought Kellyn Beck’s Defender design to life at the last, had severed all relations with Cinemaware as soon as their work was done, angered over the extreme pressure Jacob had put on them and what they considered to be a paltry financial reward for their herculean efforts. Rather than hiring computer people who happened to be good at drawing graphics, as most companies did at the time, Cinemaware began to hire conventional artists and to train them if necessary on how to use computerized tools, a key to what would become an almost uniquely refined visual aesthetic. One Rob Landeros, who had worked under Sachs on Defender, became the new art director, while several programmers toiled, as they increasingly would in a transitioning industry in general, in relative anonymity. The days of people like Bill Budge becoming stars for their programming skills alone were quickly fading by the late 1980s, as Design as a discipline unto itself came more and more to the forefront. And no company was closer to the leading edge of that movement than Cinemaware.

Jacob’s first goal for his re-imagined company must be a practical one: to port each of those first four games, a set of one-off designs custom-programmed for the particular platform on which each had been born, to the full suite of machines that Cinemaware planned to support. Doing so was no simple task, involving as it did not only developing the tool chain that would allow it but also effectively re-writing each title from scratch using the new technologies. The process could lead to some strange outcomes. The ports of Defender of the Crown, for instance, had many of the elements that had had to be ruthlessly cut from the Amiga original restored, resulting in games that played much better than the Amiga version even if they didn’t look quite as nice. Purchasers of the Amiga original of Sinbad, meanwhile, didn’t even have the comfort of knowing that their version still looked better: Cinemaware redid Bill Williams’s crude “folk-art” graphics from scratch for the ports, resulting in the very unusual phenomenon of a game that was prettier on the Atari ST and even Commodore 64 than it was on the Amiga. To add a further dollop of irony to the situation, the graphics for those better-looking versions had actually been drawn on Cinemaware’s Amigas, in keeping with their standard practice for all of their art. Ah, well, at least the Amiga version of King of Chicago both looked and played better than the Macintosh original.

In addition to all the ports, Jacob of course also needed to think about new games. With his company now established as a big name in the industry, he turned to licensed properties. This may have marked the joining-in with a mania for licenses that many industry observers were already beginning to find distressing, but it did make a certain degree of sense for Cinemaware, a company whose stated goal was after all to bring movies to monitor screens. Jacob found what he thought was a nice little property to start with, not particularly huge but with its fair share of name recognition and public familiarity thanks to countless television reruns: the old slapstick comedy trio the Three Stooges, a vaudeville act that had made the leap from stage to screen in the 1930s and remained active through the 1960s, creating more than 200 films — mostly shorts of twenty minutes or so, ideal for later television broadcast — in the process. It didn’t hurt that Jacob, something of a connoisseur of B-grade entertainment in all its multifarious forms, had a genuine, abiding passion for Larry, Moe, and Curly, as shown by the unusually lengthy manual he commissioned, dominated by a loving history of the trio that has little to do with how one actually plays the game.

Eager to get his Three Stooges game finished to maintain Cinemaware’s momentum but with his small programming team swamped by the demands of all that infrastructure and porting work, Jacob made the counter-intuitive and potentially dangerous decision to place a game’s programming in outside hands just this one last time. The Three Stooges went to Incredible Technologies, a small programming house based in Chicago. This project, though, would be different from Cinemaware’s previous outside contracts: Incredible wouldn’t be paid to be creative. Instead Cinemaware would provide all of the art and sound assets as well as a meticulously detailed design document, courtesy of Jacob’s right-hand man John Cutter, describing exactly how the game should look and play on the Amiga, the Commodore 64, and the IBM PC. As he had during the latter stages of the Defender of the Crown project, Cutter would then closely supervise — read, “ride herd over” — Incredible’s development process.

Cutter, who wasn’t a fan of the Stooges going into the project but developed a certain affinity for them over the course of it, was inspired by the games of Life he remembered from his childhood to make of The Three Stooges a computerized roll-and-move board game. Many squares lead to one of half-a-dozen or so arcade sequences, each based on an iconic Three Stooges short. About half of these minigames are reasonably entertaining, the other half unspeakably, uncontrollably awful. Among other potential fortunes and misfortunes on the game board, there’s a Three Stooges trivia contest that’s persnickety enough to be daunting even in the age of Google and Wikipedia. The rather noble first goal of the game is to earn enough money during your thirty turns on the game board — it’s single-player only, despite the board-game theme — to save “Ma’s Orphanage.” The rather creepy second goal is to go so far above and beyond that Ma gives her three beautiful daughters to the Stooges, one each for Larry, Moe, and Curly.

Released in early 1988, The Three Stooges is easily the most simplistic of all the Cinemaware games, enough so as almost to read as a caricature of Cinemaware by one of their critics who were always so eager to decry their work as a bunch of pretty graphics and sound all dressed-up with no particular place to go (a criticism that was, it must be admitted, far from entirely unfounded for Cinemaware’s games in general). Cutter has little good to say about his own design today, citing as its greatest strength a brilliant fake-out of a cold open that remains the funniest single instant Cinemaware ever put on disk.

Back in the day as well, Cinemaware was at great pains to emphasize the graphics and sound in The Three Stooges as opposed to the actual gameplay, and understandably so. It marked the first game from Cinemaware to make use of digitized images and sounds, captured from the Stooges’ own films, thus becoming perhaps the first game to deserve to be called a truly multimedia production for this the world’s first multimedia computer. Like all of Cinemaware’s games, it looked and sounded absolutely spectacular in its day on the Amiga. But all that multimedia splendor did come at a cost. Programmed with competence but, one senses, not a lot of inspiration by Incredible, you spend most of your time waiting for all that jaw-dropping media to be shuffled into memory off of floppy disk rather than actually playing. Just to add insult to injury and to further illustrate where Cinemaware’s priorities really lay, the set-piece sequences that introduce each minigame can’t be skipped. No matter how impressive they are (or were in their day), they get a little tedious by the time you’ve seen each a dozen times or more.

Larry finds his “Stradivarius” is busted, in the opening to a minigame based on Punch Drunks.

And yet, despite all these problems, I have an odd fondness for the game, counting it among the few Cinemaware productions I still find tempting to play from time to time today. My fondness certainly isn’t down to any intrinsic interest in the subject matter. The manual opens with a quote from movie critic Leonard Maltin, stating that there are two groups of people in the world: “one composed of persons who laugh at the Three Stooges and one of those who wonder why.” Among the former group was Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who, according to news reports from 1988, “sat in his tent day after day — sulking and staring at old Three Stooges movies.” As for myself… well, what can I say? I’m afraid I’m among the perplexed.

What saves the game, to whatever extent that’s possible, is the real passion for the Stooges that one can sense on the part of its creators, even if one doesn’t quite share it. Passion — or lack thereof — always comes through in a game, as it does in any creative work. Jacob emphasizes that he wanted to create a game that was “100 percent pure” to the Stooges — a game from Stooges lovers for Stooges lovers, if you will. To this day he speaks with real delight of a visit by Moe’s widow to Cinemaware’s offices, and most of all of the approval she expressed of the game’s anarchic spirit.

And there is at least a modicum more strategy in The Three Stooges than you’ll find in the likes of Life. Replacing Life‘s spinner to determine where you go next is a disembodied hand that you can stop just where you want it as long as it’s moving slowly enough. By this means you can avoid the terrible arcade games and the other undesirable squares on the board and maximize your earnings. Unfortunately, the hand gradually gains speed unless you periodically devote a turn to playing a Moe-beating-on-Larry-and-Curly minigame to slow it down. (No, I have no idea why that should have any effect.) The key strategic question of the game, such as it is, is thus when to beat and when to stay your hand. Hey, when you’re playing Cinemaware you have to take your depth where you can find it. The Three Stooges is only slap and stroll, but I like it.

Curly in a cracker-eating contest, based on Dutiful but Dumb.

In very limited doses, that is.

For Cinemaware’s next game, Jacob again turned to an existing property, albeit a more obscure one: the Commando Cody serials of the early 1950s, which portrayed the adventures of the titular hero as he flew around with his personal rocket pack to battle against enemies both terrestrial and extraterrestrial. Commando Cody not exactly being a hot property in the late 1980s, Jacob thought the license a slam dunk, to such an extent that he allowed the game to get very far along in the development process without signing a final contract with the owners of the property. He even gave at least one extended preview to a magazine of Cinemaware’s upcoming “Commando Cody” game. But when he returned to Cody’s holding company to finally settle the legalese, he found that none other than Steven Spielberg had “stolen it” from him by making a deal of his own. Jacob then turned to the contemporary comic-book character The Rocketeer, whose creator Dave Stevens had himself been heavily influenced by Commando Cody in creating his own rocket-pack-equipped flyboy. But that also fell through because Stevens was already in talks with Disney, talks that would eventually lead to the 1991 movie The Rocketeer. (I suspect that the explanation for Spielberg never doing anything with his Commando Cody license can be found here as well.) And so Rocket Ranger was completed as an entirely original, unlicensed work — hardly a huge loss, as the various flying rocketmen that preceded Cinemaware’s weren’t really notable for their vibrant personalities anyway.

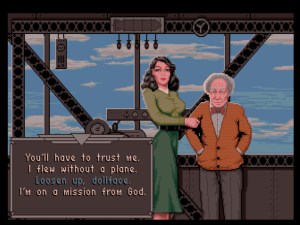

Like Defender of the Crown, the mechanics of Rocket Ranger were designed by Kellyn Beck under the watchful thematic eye of Jacob himself. Its basic structure is also the same: a light strategy game surrounded by action games that stand in for the dice rolls in the likes of Risk. And once again it plays with the tropes of history without making a whole lot of sense as history. This time we’re in an alternate version of the 1940s where the Nazis have developed space travel and made it all the way to the Moon. Unsurprisingly given advantages like that, they’ve already won World War II. But never fear! Now we’re in the future, time travel has been invented, and we’ve been sent back with a few trusty hi-tech tools — most notably, a personal rocket pack — to sway the balance of power and change the course of history. No, it doesn’t make much sense, but don’t worry about it. The important thing is that you get to fly around the world and — maybe, if you’re good enough — to the Moon to fight evil Nazis. And, this being a Cinemaware game, there’s also the usual sultry love interest along with a whole army of fetching female slaves to rescue, plenty of fuel for the libido of Cinemaware’s many teenage fans.

Whatever Rocket Ranger‘s structural similarities to Defender of the Crown, the criticisms of the latter game and other Cinemaware titles as all show and no substance were beginning to hit home for Jacob and company. This they demonstrated both by their somewhat prickly defensiveness when the subject came up and by their determination to emphasize the greater depth of this latest game. Rocket Ranger is indeed longer, more varied, and much more challenging — more on that in a moment — than the games that preceded it.

At the same time, though, it is still a Cinemaware game, which means the majority of the team’s efforts were still expended on presentation. Unlike so many flashy games then and even today, there’s a real aesthetic behind all of its screens, echoing the gargantuan Futurist sets of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis almost as much as the pulpy serials of Jacob’s childhood. It remains to this day lovely to look at, while the music — composed and programmed by Bob Lindstrom, editor of the Apple II magazine A+ but a “secret Amiga fanatic” in his free time — is also pitch perfect, owing a lot to John Williams’s work for movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark. As in The Three Stooges, digitized sound is used sparingly but effectively, including real airplane noises recorded at Los Angeles Airport, just down the road from Cinemaware’s offices. There’s also a bit of digitized speech here and there, performed by whomever was judged to have the right chops among Cinemaware’s staff; John Cutter’s wife Melanie, for instance, played the love interest. To pack all of these elements onto the game’s two Amiga disks and, just as importantly, to move it all in and out of memory during play with reasonable alacrity, Cinemaware developed a custom data format they called “Quick-DOS.” It let them compress 4 Mb of code and data into less than 2 Mb of standard Amiga disk space, and to read it in at three times the usual speed.

Cinemaware was very proud of Rocket Ranger, the first original game they’d developed completely in-house using all of their shiny new tools. And no employee was prouder than their leader and founder, who viewed the game as something of a coming to fruition of the original vision for interactive movies that had prompted him to start the company in the first place. “We really got the format right with Rocket Ranger,” he said. Never one to mince words, Jacob declared Rocket Ranger nothing less than “the best game ever done” and, as if that wasn’t hyperbole enough, “the biggest project ever tackled by a computer company” to boot. To his mind the game had “so many twists and turns, permutations of the story, and branch points that you can’t believe it.” John Cutter, who oversaw this project as he did all other Cinemaware games as the company’s only producer, said he was “more satisfied with Rocket Ranger when it was done than any other project I have ever worked on.” Both men remain very proud of the game today, especially Jacob, for whom it quite clearly remains his personal favorite of all the Cinemaware games.

For my part, I think it comes very, very close to nailing the gameplay as thoroughly as it does the presentation, but is ultimately undone by balance issues — ironically, balance issues of the exact opposite kind to those that plagued Defender of the Crown. Simply put, this game is just too hard. The arcade-style minigames are mostly entertaining but also extremely punishing, while the strategic game feels all but impossible in itself, even without the added pressure of needing to succeed at every single minigame in order to have the ghost of a chance. Just an opportunity to practice the minigames — as usual for Cinemaware games of this era, in-progress saving isn’t possible — would have made a huge difference. As it is, very few players have ever beaten Rocket Ranger. It feels like a game whose difficulty level has been set to “Impossible” — except that there are no difficulty levels. An extreme over-correction in response to the criticism of the ease with which Defender of the Crown can be won, it serves as one more object lesson on the need to test games with real players and to work however long it takes to get their balance exactly right.

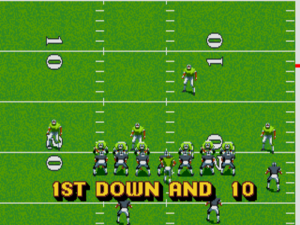

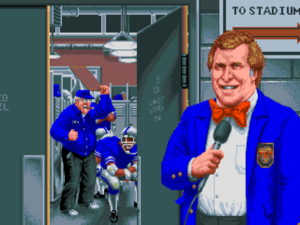

Cinemaware’s final release of 1988 marked both a major departure from their usual brand of interactive movies and an innovation easily as prescient in its own sphere as Defender of the Crown had been in its. It was called TV Sports: Football, and it introduced a whole new approach to the idea of the sports simulation.

Those wishing to trace the history of the modern “EA Sports” stripe of sports simulations, cash cows that generate billions of dollars every year, generally reach back to one of Electronic Arts’s first titles, a little 1983 basketball game called One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird. From there the history proceeds to John Madden Football, the 1988 genesis of the series that would come to personify the whole genre of mainstream sports games when it reached Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo in 1991. All of this is valid enough, but it nevertheless misses the other important blueprint for sports gaming as it would come to be known in the 1990s. “Early on,” says Jacob, “I saw that people relate to sports through television and the way to do it was to emulate the TV broadcast. I think of EA Sports and I go, ‘Yes, that was my idea.'”

What’s striking about TV Sports: Football and all those games that would follow is that these aren’t really simulations of their sports as real players or coaches know them. They’re rather simulations of the televised presentations of their sports, interactive spectacles that cleave as closely to the programs we see on our televisions as they possibly can. This is, when you stop to think about it… well, it’s kind of weird, isn’t it? Cinemaware went so far as to include spoof commercials (“Stop Sine Nasal Spray: We’re not #1… but we’re right up there!”) in their game. The modern sports-simulation landscape is an amalgamation of Electronic Arts’s early forays into league licensing and star-athlete branding with TV Sports: Football‘s faux-television presentation.

There’s much of social or philosophical import that we might say about lives that have become so mediated that we crave an extra layer of it even within our mediated simulations. But then, for many — most? — of us this is what sports are today: not a beat-up glove, a homemade bat, and a brand new pair of shoes out there on the field, but rather afternoons gathered around the television. We’re the people who go to a real event and find that it just doesn’t feel right without the comforting prattle of the announcers, the people who make it a point to remember to bring a radio next time. Is this part of the tragedy of the modern condition? I don’t know. You can debate that question for yourself. Suffice to say that Cinemaware struck a rich cultural vein with TV Sports: Football that continues to geyser to this day. Sports as spectacle, sports as multimedia entertainment… this is what the people really want, not sports as icky sweat and effort.

How appropriate then that it was the Amiga, the world’s first multimedia computer, that first brought it to them. Another design by the stalwart John Cutter, TV Sports: Football comes complete with everything you’d expect from a Cinemaware take on football: two disks worth of thrilling graphics and sound, buxom cheerleaders to keep the old spirits up, and gameplay that’s a little sketchy but serviceable enough until you figure out the can’t-miss tricks that can yield a touchdown on every drive and rack up scores of 70-0.

Although no later Cinemaware game would ever approach the sales numbers of Defender of the Crown, each of this new generation of titles did quite well in its own right, not only in North America but also in Europe, where Cinemaware was becoming just as well known as they were on their home continent thanks to a distribution deal with the major British publisher Mirrorsoft. Like Americans, Europeans found Cinemaware’s games just too sexy to pass by even if they ought to have known better — and, with Amigas already selling so much better in some European markets than they were in North America, there were a lot more customers there with the computer best equipped to strut Cinemaware’s stuff. It was easy enough to overcome some subject-matter choices that weren’t terribly well-calibrated to European sensibilities. The Three Stooges, for instance, were virtually unheard of even in English-speaking Britain, and American football also remained a mystery to most Europeans, much less the television broadcasts on which Cinemaware was riffing in TV Sports: Football. (One British reviewer decided there was nothing for it but to start from first principles: “The ball has to cross an imaginary barrier that rises horizontally from the opposition’s base line. This move is known as a Touchdown.”) Rocket Ranger represented the most uncomfortable culture clash of all; Cinemaware was forced to strip out all of the Nazi imagery and make the bad guys into generic aliens in order to sell the game in the Amiga hotbed of West Germany.

Sizzle without steak or hat without cattle though their games still to some extent may have been, Cinemaware was clearly doing something right. Jacob was happy to reinvest their earnings in yet bigger, bolder plans, all still in service of his vision of games as overwhelming multimedia experiences. We’ll see where that vision took him and his company next in future articles.

(Sources: Amazing Computing of July 1988, November 1988, and June 1989; Amiga Power of November 1991; Commodore Magazine of November 1988; Computer and Video Games of April 1988; The Games Machine of April 1988; The One of January 1989 and June 1989; Retro Gamer 123; the book On the Edge by Brian Bagnall; Matt Chat 292; two Gamasutra interviews of Bob Jacob, one by Matt Barton and the other by Tristan Donovan.

Rocket Ranger and TV Sports: Football are available as part of a Cinemaware anthology on Steam. You can download the Amiga version of The Three Stooges from here if you like.)