After the first Ultima and Wizardry games debuted within months of one another in 1981, dizzying formal or technical leaps were few and far between in the realm of the CRPG for the next half-decade. Richard Garriott steadily expanded on Ultima I‘s decidedly limited scope of possibility with each new iteration of his series, but never came close to abandoning the basic structure that made an Ultima an Ultima. In terms of technology and interface — theme and content were a different matter — the Ultima series was all evolution, not revolution; anyone who’s played any of Ultima II through Ultima V will immediately recognize Ultima I as an earlier, rougher swathe cut from the same cloth. Sir-Tech, meanwhile, did far less work than Garriott on their own defining classic Wizardry, content to simply pump out iteration after iteration of the same game.

If Sir-Tech’s particular brand of sloth was almost incomprehensible, in the broader strokes the Ultima and Wizardry developers’ decision to stick with their provably enjoyable, commercially successful approaches is hardly surprising. What’s much more so is how slavishly most other CRPGs chose to model themselves after one or the other. One only had to glance at mid-1980s hits like Questron or The Bard’s Tale to know where their ideas were coming from (for the record, Ultima and Wizardry respectively). Those games that did try to go their own way, like Shadowkeep with its unholy union of Wizardry-style dungeon delving to a Zork-style parser interface, made you wonder why they bothered, served only to make you appreciate the two proven CRPG templates all the more. It was as if those two pivotal early efforts had gotten so much right that there just wasn’t much innovation left to be done beyond tinkering at the margins. Questron and The Bard’s Tale were better games in some ways than their inspirations, offering better graphics and more to see and do, but they were, once again, evolutions, not revolutions. Where were the really bold and exciting new ideas?

They began to arrive only in the latter half of the decade, firstly in the form of The Faery Tale Adventure, the game I wrote about in my last article, and shortly thereafter in that of Dungeon Master, the one I want to write about today. Even in them, one can still see the old templates in the broad strokes. The Faery Tale Adventure, a free-roaming game of open-world exploration, quite clearly draws from the Ultima games with its selection of magical gems and totems, its overhead perspective, and its system of magical gates for traveling around its sprawling world. But just as much about it is entirely new: its day-to-night cycles (a year before Garriott nicked the idea for his own Ultima V); its free-scrolling movement; its action-based combat. Likewise, Dungeon Master is very much a tactical dungeon crawl in the best tradition of Wizardry.

But what a dungeon crawl it is! Having agreed to work from that very traditional premise, its developers gave themselves permission to innovate wildly within it and to question every assumption of its forefather. The result is as dramatic a leap beyond Wizardry as that game had been beyond the earliest proto-CRPGs like Temple of Apshai. Wizardry had brought with it a feeling that its developers had finally figured something out that the rest of the software world had been groping toward for some time — had gotten something fundamentally right at last. More than six years later, Dungeon Master arrived carrying much the same aura.

Indeed, Dungeon Master would prove to be almost too good at what it did, would have the same almost stultifying effect as earlier had Wizardry on the dungeon crawls that followed. It would seldom if ever be even equaled in the years immediately following its release, and wouldn’t be clearly bettered until something called Ultima Underworld dropped five long years further on. The dungeon crawl, it seemed, was just a quantum sort of genre.

Dungeon Master is such an important game that I feel I need two articles to do it justice. This first one will tell the story of its long gestation and birth and the huge rewards its parents finally reaped for their efforts. The second will delve into the game itself, to properly explain why it’s such an important entry in its field and why I consider it one of the most remarkable feats of its era.

The road to Dungeon Master begins more than six years before its eventual release, with, appropriately enough, those original Ultima and Wizardry games. Doug Bell and Andy Jaros were already good friends as well as undergraduates in chemistry at the University of California, Irvine, when Jaros was given an Apple II by his parents just in time for those seminal releases. The pair played them obsessively, and soon decided, much like thousands of others, that they could create a dungeon crawl just as good as Wizardry for themselves. They decided to call it Crystal Dragon; in a move that must have seemed hilariously clever to a couple of young chemists, they named the company they would form “PVC Dragon” to match. Bell would be the programmer, Jaros the artist, and they would share the role of designer.

The pair had big ambitions, incorporating themselves from the beginning and even managing to attract some investors. Emulating their hero, Wizardry programmer Robert Woodhead, they programmed their would-be Wizardry killer in Apple Pascal. They worked doggedly on it through their mutual graduation in 1983 and beyond. But, as Jaros puts it, “the money was always running out.” The pair had to accept that they couldn’t make the game all by themselves. “We sent six letters out to some software companies in the Los Angeles and San Diego areas,” remembers Jaros. “One of them got us in touch with Wayne Holder at FTL Games. The rest, as they say, is history.” In short, Bell and Jaros found themselves in Software Heaven.

Software Heaven was the name of the little company of several years standing that was owned and operated by Holder, a programmer a generation removed from the PVC Dragon boys. Holder and his company, known in its earliest years as Oasis Systems, had made their first money in the young software industry in 1981 through a program he called simply The Word, a spellchecker he had first developed to help his wife Nancy, an author of romantic fantasy and horror novels and an ever-helpful supporter of his own projects, in her work. Oasis/Software Heaven made quite a number of similar tools for writers in the years that followed. But already in 1982 conversations with an old college buddy named Bruce Webster, a dedicated player and amateur designer of games of both the analog and digital varieties, led Holder to diversify, to start a new division of his company to make games under Webster’s guidance. He named it “FTL Games” — FTL for “Faster Than Light.” It would, as we’ll soon see, prove to be a very ironic title.

The first and, as it would transpire, last game that Webster wrote for the new FTL has become something of a cult classic in its own right. Inspired by Webster’s Mormon faith, Sundog: Frozen Legacy is the story of a small group of space colonists adrift on the galactic frontier, whom you, a pilot with a little star freighter, must succor by trading for the goods they need to survive and expand. It was released in March of 1984 on the Apple II, whereupon its mixture of trading, space combat, and CRPG-type character mechanics yielded stellar reviews and respectable sales. Webster, however, had found the process of coding 80 to 90 percent of such a complex game all by himself unbelievably draining. Unable to face the prospect of another such project, he left FTL that fall, shortly after completing a version 2.0 of Sundog that fixed some bugs and added some new features.

Webster’s abrupt departure left Holder high and dry, with a successful game but no programmers to make a follow-up. Meanwhile the writing seemed to be on the wall for the other part of his business. His writing aids had done very well for him for a couple of years, but the serious productivity market was getting to be a tougher and tougher one for a small company, dominated as it now was by big names like Microsoft, Ashton-Tate, and Lotus, with big marketing budgets to match. While he would keep his hand in as a spellchecking expert for several years to come, often by writing pieces of the firmware for dedicated hardware word processors from companies like Magnavox, he was already coming to see his company’s long-term future as necessarily a games-oriented one if it was to have a long-term future at all. It was for this reason that he found these two bright young sparks Doug Bell and Andy Jaros, along with their CRPG in progress, so appealing. Their game was even coded in Pascal, the same language as Sundog. He signed PVC Dragon to not so much a development as a devouring deal, bringing Bell and Jaros in-house to become the nucleus of a new version of FTL. The initial plan was to finish up Crystal Dragon and get it out as quickly as possible, then move on to the next game. But very, very few things at FTL ever happened in quite such a tidy — or timely — way as that.

Crystal Dragon almost immediately proved a more complicated proposition than Holder had anticipated. Bell and Jaros had lots of ideas, but not all of them were practical on the little Apple II. For all the cockiness with which they had embarked on their Wizardry killer, they found themselves facing a problem well known to all too many other 8-bit CRPG developers: it just wasn’t clear how to dramatically improve on the Wizardry formula on such limited hardware.

When Jack Tramiel, newly installed owner of the post-videogame-crash Atari Computer, announced the 68000-based Atari ST line in dramatic fashion at the January 1985 Winter Consumer Electronics Show, Holder decided that they might just be able to dispense with said limited hardware. Like plenty of other pundits and industry figures, he felt sure that the ST, which in the terms of 1985 offered a staggering amount of computing power for the price, must become the mass-market successor to Tramiel’s earlier masterstroke the Commodore 64. Sundog had done quite well in the crowded, uncertain Apple II market. How well might the same game, with improved graphics and sound and a mousefied interface, do in the virgin territory of the ST? Determined to find out, Holder pulled Bell and Jaros off of their game and set them to work porting Sundog to the ST just as soon as he could get his hands on actual ST hardware.

Released in time for Christmas 1985 thanks to herculean efforts on everyone’s part, the re-imagined Sundog arrived to a still tiny base of ST users, but one that was absolutely starving for quality games for their new toys. It did very well, even better than the Apple II version despite the tiny fraction of potential customers the ST offered in comparison. The small-pond theory had worked brilliantly, cementing a loyalty to the ST that would lead them to create this oft-overlooked platform’s best-selling game of all time.

FTL turned back to Crystal Dragon, which they soon renamed to Dungeon Master — a name so obvious it was amazing that no one had yet claimed it. Now, however, it was to be rewritten from scratch on the ST. Thanks to the power of the ST, FTL should at last be able to explode the old Wizardry template without being slowly pulled back to the status quo by the limitations of the hardware. Key to the re-imagined Crystal Dragon from the beginning was that it should be a real-time experience, giving it a very different personality from the cool tactical challenge that is Wizardry. “The games at that point had all been turn-based and you could take as long as you wanted to think about what you were going to do next,” says Bell. “We knew we wanted to put the player under the pressure of time.” Wizardry‘s tiny window on its dungeons would be blown up to a view that filled at least half the screen. The player would no longer be isolated from the environment; she would be able to click directly on the world view to interact with the things — and creatures — in it. These new ideas, and the many more that would continue to spiral out from them for months to come, were part of an overarching determination to create an embodied CRPG experience. “How do you go from being a player to being ‘in’ a game?” asked Nancy Holder. Almost every new aspect of Dungeon Master exists as an answer to that question.

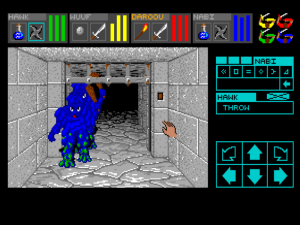

Dungeon Master the embodied experience: I’ve just reached directly into the world to hit the button and lower the door, which is now crushing the Blue Meanies beneath it as it tries to close.

Dungeon Master on the ST first came to life before the ST Sundog had even made it into shops, as a proof of concept created by Bell to see whether the large pseudo-3D, first-person view would be possible. Bell used what’s known in graphics theory as a “painter’s algorithm” to draw each screen. The background was first pieced together jigsaw-style from separate sprites depicting walls, floor, ceiling, doors, etc. Objects and monsters that should appear over it were then sorted in order from farthest to nearest, and finally drawn in one by one, thus ensuring that those closer obscured those farther away. It worked, but the performance of the demo, which was still coded in Pascal, left something to be desired, even on the mighty ST. Bell therefore “spent three weeks learning C,” the native language of the ST’s operating system. The performance of the re-coded demo proved “better than expected.” Dungeon Master was a go.

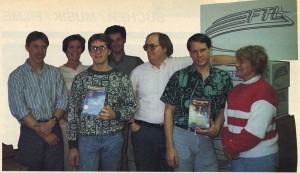

Some of the FTL crew. From left: Joe Holt, Deirdre Poelter, Mike Newton, Russ Boelhauf, Wayne Holder, Andy Jaros, and Sylvia Esposito.

With its founder and head himself a fine programmer, FTL was nothing if not a classic example of a purely technology-driven company. That can create a danger in the form of a tendency to continue iterating endlessly over the same project instead of just getting things finished and out the door. FTL would hardly be immune to that danger — in some fourteen years of existence they would manage to release exactly three original games and two sequels — but their obsessive perfectionism in executing all of their bold new ideas would nevertheless come to define Dungeon Master almost as much as the ideas themselves. Bell had chafed at the way that Sundog had been coded on the Apple II, and the form in which, pressed for time, he’d had to recreate it on the ST: as a big pile of hand-crafted, machine-specific code. Resources at FTL being limited, this approach would prevent them from ever porting it beyond those two platforms, despite the success it enjoyed there. Better, thought Bell and Wayne Holder alike, to first write a set of tools for writing Dungeon Master, along with an engine that could run the tools’ output on both current computers and those still to come. They could be loyal to the ST, but not to the point of stupidity. And the same tools could later, of course, be used to make more games as well as ports. “We knew,” says Wayne Holder, “that there was absolutely no chance of getting our money back with just one version of Dungeon Master. We had to set up a system that would serve as a foundation for later games.”

It was far from a new idea in game development, but few others of FTL’s era would take it quite as far as they did. A new programmer, Mike Newton, was hired just to work on the design tools. Applications like the Dungeon Construction Set, which let one design and populate an entire dungeon level from a unified GUI interface, grew into impressive feats in their own right. Equally impressive was the compression technology that FTL developed from scratch, which allowed them not only to run the game on Atari’s low-end 512 K 520 ST model but to ship it on a single single-sided disk; the entire game, code and graphics included, consumed less than 400 K on disk. Helping the cause greatly was the fact that the game, being virtually story-less until you arrive at the final showdown, needed contain very little text, a greedy eater of disk space.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you may have already remarked certain parallels between the approach of Infocom and that of FTL — namely, the idea that the best tools are necessary to craft the best games. The comparison was not at all lost on Wayne Holder, who set out with the explicit goal of making his company the Infocom of the CRPG world, a comparison that also extended to heavily emphasizing testing and player feedback.

We set a high goal. We want to become in the field of role-playing games the counterpart to what Infocom has achieved in the field of text adventures: the best technically, who also have the best game designs and — contrary to Infocom — also the best graphics. Therefore we spent several months just working on polishing and improving/detailing the interaction for Dungeon Master. We let dozens of folks playtest, from complete pros to people who had never seen a computer nor dungeon before. We listened to every proposal and modified the user interface several times. We did think about things that do not appear in Dungeon Master at all, which we however will need in other RPGs, and have programmed them along the line, too. Now we have a complex development system that enables us to program relatively quickly RPGs with a user interface similar to Dungeon Master’s. And it won’t stop at fantasy titles alone. We are thinking about science-fiction games, detective stories, and about a couple of new things nobody has yet done.

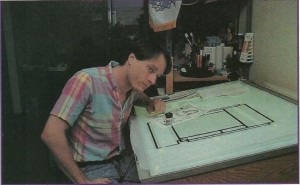

The tricky, performance-sensitive code of the engine itself was created by Bell and another new hire, Dennis Walker, while Jaros continued in the role of artist, drawing his images on the ST using Activision’s Paintworks. Rounding out the little team was Wayne Holder, who oversaw the whole thing and also served as the de facto sound programmer, coaxing out of the machine’s limited sound chip some of the first examples of sampled audio to appear in an ST game. Far from a typical executive, he remained always intimately involved with the process of creation. “I think some of the biggest conceptual contributions were made by Wayne,” notes Bell, “particularly with regard to the user interface.” Nancy Holder was also on-hand to offer occasional insight and to write the accompanying fiction, something about a Grey Lord and a Firestaff that can be safely ignored until the climax, when you suddenly have to ask yourself what the hell just happened. To offer more story would have been to go against one of the guiding philosophies of the game. “I wanted people to have a lot of tall tales to tell when they’d finished the game,” says Wayne Holder. “And I wanted those tales to be unique. We are working toward the point where the story is scripted entirely by the player. We take you to the starting point, but from then on it’s up to you.” Perhaps more valuable than Nancy Holder’s story-making were her insights into the psychology of horror that lent the game tension and texture: “We tried to make it scary so that the player could feel engaged. We tried with background noises and all kinds of other things to make it creepy.”

The further the design progressed, the further it moved away from the structure of Wizardry, and with it from Wizardry‘s own inspiration of tabletop Dungeons and Dragons. Instead of having a set class, characters can advance simultaneously in all four disciplines of fighter, wizard, ninja, and priest. Experience is earned not through killing monsters or accomplishing goals, but simply by practicing the skills in each discipline and thus getting better at them. Combat, taking place now in real time, is a much more frenzied, hectic affair, dependent as much on the player’s reflexes as the characters’ skills. I’ll have much more to say about these new ideas and many others in my next article, but suffice for now to say that, if Wizardry is Dungeons and Dragons adapted to the computer, Dungeon Master is a clean-slate re-imagining that takes only a handful of fundamental concepts — a dungeon to be delved, monsters to be fought, treasure to be collected, characters to be improved — as sacrosanct. Everything else is up for renegotiation. Bell sets great store by the fact that, while he and Jaros were hardcore aficionados of Dungeons and Dragons and previous CRPGs, the others at FTL had little to no experience with the genre. They continually asked why their game needed to abide by this or that more or less arbitrary tradition; such constant questioning “saved the game from being an extension of what had already been done.” Dungeon Master is a computer game through and through, its tabletop roots left far behind. Tellingly, it’s just as obviously a progenitor of Doom as it is a successor to Wizardry.

Of course, innovation on such a scale would take time even without FTL’s perfectionist tendencies. Dungeon Master was first discussed publicly at the Summer CES in June of 1986, to which FTL brought a very limited, non-interactive demo that’s mostly devoted to a lengthy text scroll full of purple prose. The brief glimpse we get of the game itself in action shows that, while the basic concept is in place, much of what’s been done needs further refinement. And there’s still more that would be seen in the finished game that’s yet to be even begun. The interface, for instance, is more cluttered than what we’d seen in the final game, the mouse pointer that in the shape of a disembodied hand would be your means of poking and prodding at the environment not there at all. And there’s not a single actual monster to be seen.

FTL’s original plan to make the game available in time for Christmas 1986 slipped and slipped. To keep the buzz alive, they regularly demonstrated the work in progress for ST user groups. “That was my method of knowing we were on the right track,” says Wayne Holder. “When we started showing the game, it was always invariably quiet, then the users would ask a ton of questions.” Dungeon Master was the most hotly anticipated piece of vaporware in ST circles for months on end.

In the end, Dungeon Master spent more than two years in active development. All that time was spent doing many of the things you might expect, adding features and puzzles and new types of monsters, but much was also spent paring back the design, honing in on what really mattered. Like most elegant designs, Dungeon Master is marked as much or more by the surface complexities it lacks as those it contains. For good reason has it long been a truism in software design that the best programs are usually those that appear the simplest on the surface. Wayne Holder proved to be the group’s Steve Jobs, with a knack for slicing through the cruft to arrive at what mattered. He demanded a game as easy and instinctive to use as a “screwdriver.” Doug Bell:

I was working on this complex system where you could look down at the floor and you could pick up things around you, and Wayne says, “Well, it’s right there, why can’t I just reach in and pick it up?” That was sort of a “well, yeah” moment. And Wayne was actually responsible for a lot of those moments. He would just come in and say, “Why don’t you do it that way?”

With Sundog out and doing well, FTL had a sustaining source of income through all the experimentation and refinement. The fourteen dungeon levels that make up the game, whose design was a joint effort on the part of the entire team, were refined just as obsessively as the technology and user interface. Dungeon Master got played constantly for months, first by the team themselves and their close friends, and then, near the end of the process, through a serious outside beta test, all in the name of getting that elusive balance between fun and frustration just right. (That said, you can never please everybody: one tester reportedly sent back a broken disk accompanied by the message, “Take this aggravating piece of shit and shove it up your ass.”)

The work paid off. As impressive as Dungeon Master is for its technical and formal innovations, it’s at least as impressive as a piece of pure design craft. It is, simply put, one superbly crafted CRPG, rivaled only by the first couple of Wizardry games among its predecessors in its sheer attention to detail. I will, once again, have much more to say on this front in my next article, but it’s important to note even here how rare it is to see such attention to design in a technical game-changer like Dungeon Master. Normally bold new gaming concepts are attached to somewhat wonky designs, to be shaped and refined by succeeding efforts; even Infocom’s early games had their share of lousy puzzles. But FTL, like Sir-Tech before them, hit a home run in their first at-bat.

David Darrow’s Dungeon Master cover art has become some of the most iconic of its era. It was painted from photographs he took in his studio, with his wife playing the candelabra-holding spellcaster, Andy Jaros the squirrely fellow pulling on the torch, and a “really huge guy” from a local gym the barbarian fighter.

Dungeon Master slipped quietly into American stores on December 15, 1987, far too late to take advantage of the Christmas rush. Nor was it all that lavishly advertised. FTL seemed to have a certain sense of austerity baked into their very DNA, reflected equally by the modest advertising campaign as it was by the aesthetic minimalism of the game itself, which offered no music or other extraneous flashiness, just those things that really needed to be there.

But it didn’t matter. If ever a game was sellable by word of mouth, it was this one. Already in the February 1988 issue, the Michigan Atari Magazine was noting that “messages asking question and giving playing hints are appearing in unprecedented numbers on CompuServe and other information services, as well as local BBS systems.” Dungeon Master did staggeringly well right out of the gate, especially considering how small the installed base of STs really was. That same magazine noted that “Dungeon Master has become so popular, it took me several weeks to locate it in stock anywhere” — and this just two months after a very quiet release. FTL was positively overwhelmed by the demand, fighting for months a losing battle to ship games fast enough. They printed a sign to send to software dealers, saying “Yes! We have Dungeon Master!,” which they could hang in the window during those usually brief periods when that was indeed the case.

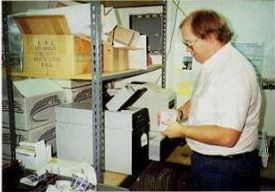

Wayne Holder personally copies Dungeon Master disks. FTL’s state-of-the-art in-house disk duplicator, capable of copying 100 disks at a time, was key to their state-of-the-art copy protection.

Yes, the ST community went crazy for Dungeon Master, first in North America, soon enough in Europe, where it was packaged and distributed by the big British publisher Mirrorsoft. With the ST itself so much more popular overseas, more than two-thirds of Dungeon Master‘s eventual sales would be made through Mirrorsoft. To help them along, FTL funded full translations into German and French, still a relative rarity in the industry at that time. Doug Bell would have it that Dungeon Master sales at at least one point reached more than 50 percent of the total installed base of Atari STs — in other words, that more than one out of every two people with an ST had purchased Dungeon Master to play on it. While that seems a little unbelievable — especially given that, thanks to Jack Tramiels’s tight-lipped business practices, no one was ever quite sure how many STs were actually out there anyway — it’s a marker of Dungeon Master‘s insane popularity that it is indeed only a little unbelievable. During 1988 it really did seem that everyone who owned or had access to an ST was playing Dungeon Master. Its effect on their ranks can perhaps be compared only to the original Adventure, the game that famously stopped the institutional world of the PDP-10 dead for two weeks while everyone tried to solve it.

Helping Dungeon Master‘s commercial cause greatly was the game’s copy protection, which like just about everything else about it was innovative and technically state of the art, such that it would take months rather than the usual hours for a completely cracked version to emerge — an eternity on the calendar of the most notorious piracy demographic, the adolescent boy. Throughout those long months, the only way to play Dungeon Master was to buy a copy. A Dungeon Master original therefore became the only original game in quite a number of otherwise ill-gotten collections. The release of Dungeon Master marks one of the few occasions in the history of the software industry when copy protection clearly and incontrovertibly did do its job, generating tens if not hundreds of thousands of sales that wouldn’t have been there otherwise.

The 68000 Wars hadn’t been going all that well for the ST following the release of the Commodore Amiga 500, superior in most technical respects to a similarly low-end ST and for the first time much too close for comfort in price. Amiga owners loved to taunt ST owners about the latter platform’s inferior graphics and sound and lack of multitasking and, now, its inferior sales as well. Hard as it may seem to believe that a single game could serve as a viable riposte to such comprehensive taunts, this one was so impressive that it made exactly that: “Yes, well, we have Dungeon Master!” There wasn’t much to be said by Amiga owners in response; everyone knew they wanted it, lusted after it, were jealous as hell.

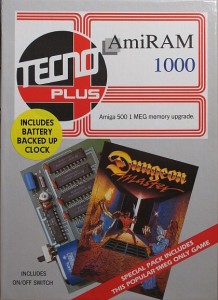

But, soon enough, they got it, and ST owners lost their bragging rights again. FTL had designed their game engine to be portable from the beginning, and the Amiga, by far the computer most technically similar to the ST, was the obvious first target. The biggest stumbling block proved to be memory. The vast majority of Amigas out there at the time still had only 512 K, the same as the low-end ST for which Dungeon Master had originally been designed, but thanks to a more memory-hungry operating system FTL just couldn’t find a way to get the game running in that space. They made the painful decision to require a full 1 MB of memory, becoming the first prominent Amiga game to do so. The decision doubtless hurt sales to some extent, but such was Dungeon Master‘s burgeoning cult that it likely did just as much to drive sales of Amiga memory expansions. Just as Commodore’s own European subsidiaries had taken to packaging Amiga 500s with the latest hit games, at least one maker of RAM expansions, Tecno, acknowledged why their customers were really interested in their product by selling a sort of Dungeon Master playing kit that included the game in the same box as the memory expansion needed to play it. Many more games began to follow Dungeon Master‘s lead in demanding 1 MB, and by 1990 it had become the effective standard minimum.

In return for their patience and their indulgence in expanded memory, Amiga owners were rewarded with bragging rights of their own over their ST rivals. While the graphics in the Amiga Dungeon Master remained unchanged, FTL had taken advantage of the Amiga’s superior sound hardware to enhance the experience: monsters moving about the rooms and corridors near your party were now heard in realistic stereo. Far from just a gimmick, the subtle stereo soundscape was a real boon to situational awareness, making Dungeon Master the first of the great headphone games.

Additional ports to the Apple IIGS and MS-DOS followed. Ever the tech-driven company, FTL designed their own “sound adapter” to package with Dungeon Master on the latter platform; it replaced the beeps and squeaks that were the only noises that PC clones could normally make with sampled digital sound effects, just like all the other platforms got to enjoy.

An entire cottage industry sprang up around this single game and its single fourteen-level dungeon that’s perhaps comparable only to the one that came to surround the original Wizardry. Companies sprouted like weeds out of garages and back offices to offer character editors, map editors, and, most of all, information: tactical hints on how best to combat the various monsters, maps of the dungeon levels and solutions to the many puzzles and traps found therein. At one time there were a dozen or so alternative hint books and hint disks duking it out with FTL’s own official volume. FTL themselves released the ultimate Dungeon Master lifestyle accessory, a CD — Dungeon Master: The Album — containing tunes inspired by the game, with tracks bearing titles like “Hall of Champions,” “The Adventure Begins,” and “Riddle Room.” The music had originated as embellishments to yet more ports, this time to various Japanese consoles and computers. Dungeon Master soon became a big hit in the Land of the Rising Sun as well, making it as close to a truly global phenomenon as it was realistically possible for a computer game to be in those days.

All this success prompted the inevitable legion of copycats hoping to get a piece of the same action. Some of them, like Westwood Associates’s Eye of the Beholder and Lands of Lore series, did indeed do very well for themselves, and are still remembered with considerable fondness today. To my mind, though, none ever quite matched the taut, minimalist elegance of the original. The first game of its kind, Dungeon Master is also probably the last that a student of gaming history really needs to play, until we get to Ultima Underworld, which replaces Dungeon Master‘s step-wise movement and pseudo-3D with a smoothly scrolling truly three-dimensional view and thereby revolutionizes the genre yet again. As Wayne Holder said a few years after Dungeon Master‘s release:

I haven’t really seen anything where they have done much more than follow in our footsteps. We expected to be imitated, and we figured that people would advance the state of the art, but it was amazing how many of the things we did got completely borrowed. The movement arrows on the screen, for example. We must have experimented with dozens of different combinations before arranging them the way we did. That’s really where your investment of time is, working out what works and what doesn’t. It’s amazing how many games I look at and see those same movement arrows.

Unfortunately, FTL proved to be like their competitors in that their own later efforts also pale in comparison to the first Dungeon Master. Making the game had been an exhilarating experience, but as draining as any other difficult artistic birthing. Comparisons to the world of film abound among the FTL alumni. Nancy Holder learned a new sympathy for movie directors, who, after finishing a movie, “sometimes take years before they direct another,” while Wayne Holder recalls “Robert Rodriguez’s comment that all he wanted to do when he made El Mariachi was to make enough money to make another film. He was not prepared for it to be successful, and I felt exactly like that.” Given FTL’s focus on technology almost for its own sake, and given that they already had a proven, hugely successful design on their hands, it was easy — perhaps a little too easy — to just focus on making all of the ports as good as they could be, on engineering gadgety distractions like that MS-DOS sound adapter. Wayne Holder’s claim in 1988 that the technology they’d developed for Dungeon Master would soon allow FTL to pump out four to six games every year sounded hugely overoptimistic even then, but FTL’s failure to serve up anything new at all for long, long stretches of time is nevertheless a little shocking. He often claimed that FTL had “several” titles in development using the Dungeon Master technology, among them an intriguing-sounding horror game that comes up in a number of interviews; it might just have marked the beginning of the survival-horror genre several years before Alone in the Dark. We also heard regularly of a science-fiction scenario, possibly a sequel to Sundog. Neither ever materialized; it appears there was quite a lot of wheel-spinning going on at FTL. Wayne Holder’s dream of making FTL the Infocom of CRPGs petered out in the face of their failure to actually, you know, make games. FTL became an Infocom that could never quite get past Zork.

Doug Bell notes the failure to build on Dungeon Master in a timely way as his greatest regret from his days with FTL: “We got so busy doing ports of the game that we didn’t end up creating enough scenarios.” Wayne Holder believes FTL’s single biggest mistake to have been not to have sold their in-house Dungeon Construction Set, quite a polished creation in its own right, and “let people create their own stuff. I was afraid it would dilute the whole cachet, and people would come up with tacky stuff, but people like to author stuff.” One can imagine an alternate timeline where FTL did what they so obviously most loved to do — work on technology — and let others make games with it. Ironically, some of the more ambitious Dungeon Master obsessives reverse engineered the data format and essentially did just that; as already mentioned, a number of dungeon editors of various degrees of utility were among the products of the third-party cottage industry spawned by Dungeon Master. None, however, had anything like the polish or clout to create a community for entirely new games running in the Dungeon Master engine. An official FTL Dungeon Construction Set might just have had both.

When it did arrive on the Atari ST two years after the original, the first semi-sequel felt a little anticlimactic and a little disappointing. Originally planned as a mere expansion pack and turned into a standalone game only at the last minute, Chaos Strikes Back ran under almost exactly the same engine as its predecessor, yet was considerably smaller. Even its box art featured the same picture as the original, cementing a difficult-to-avoid impression that FTL hadn’t exactly gone all-out to make it everything it could be. Perhaps worse, Chaos Strikes Back catered strictly to hardcore Dungeon Master veterans. It implemented nothing like the masterful learning curve of its predecessor, and stands today alongside Wizardry IV as one of the toughest, most nasty-for-the-sake-of-it CRPGs of its era. There are hardcore players that love it; I’ve seen the original Dungeon Master gleefully described as nothing more than an extended training ground for the real fun of Chaos Strikes Back. But, while making a hard-as-nails game may not be an illegitimate design choice on its own terms, it was a commercially problematic one. In being so off-putting to newcomers who might wish to jump aboard midstream, FTL was all but ensuring that every successive title in the series would sell worse than its predecessors. This marks the one unfortunate place where FTL blindly followed the lead of Sir-Tech and Wizardry instead of blazing their own trail.

What FTL themselves came to consider the first proper sequel, Dungeon Master II: The Legend of Skullkeep, arrived only in 1994, almost seven years after the original. By now the Dungeon Master mania had long since died away, and FTL, for all those years a one-product company, was in increasingly dire straits as a result. The situation gave this belated release something of the feel of a final Hail Mary. And like most such, it didn’t work out. Rather astonishingly for a company that had built its reputation around technical innovation, Dungeon Master II was painfully outdated, still wedded to the old step-wise movement long after everyone else had gone to smooth-scrolling 3D environments in the wake of Ultima Underworld and Doom, the very titles the original Dungeon Master had done so much to inspire. It garnered lukewarm reviews and worse sales, and FTL went out of business in 1996.

That, then, is that for the commercial history of FTL and Dungeon Master. Yet it doesn’t begin to do justice to the game itself as a work of enormous technical innovation, and as a great piece of game design on anyone’s terms. We’ll try to correct that failing next time, when we’ll do a little real-time dungeon delving together to hopefully see why everyone was making such a fuss back in 1988 — and, for that matter, why I’m continuing to do so today.

(Sources: Michigan Atari Magazine of February 1988; Retro Gamer 10, 34, and 105; Power Play of April 1988 and March 1990; ST Action of November 1989 and June 1990; ACE of April 1990; Byte of November 1981 and July 1982; interview with Wayne Holder in Dungeon Master II: The Official Strategy Guide by Zach Meston and J. Douglas Arnold. The go-to place on the Internet for all things Dungeon Master is The Dungeon Master Encyclopedia, a rather staggering assemblage of technical and historical information, while Maury Markowitz’s interview with Bruce Webster fills in the story of FTL before Dungeon Master.)