With the notable exception of Electronic Arts, the established American software industry was uncertain what to make of the Amiga in the wake of its initial release. Impressive as the machine was, it was also an expensive proposition from a parent company best known for much cheaper computers — and a parent company that was in a financial freefall to boot. Thus most publishers confined their support to inexpensive ports of existing titles that wouldn’t break the bank if, as so many expected, neither Commodore nor their Amiga were still around in a year or so.

Disappointing as this situation was to many early Amiga adopters, it spelled Opportunity for many an ambitious would-be Amiga entrepreneur. Just as early issues of Amazing Computing, the Amiga’s most respected technical magazine, carry with them some of the spirit of the original Byte magazine, of smart people joining together to figure out what this new thing is and what they can do with it, the early Amiga software scene represents the last great flowering of the Spirit of ’76 that had birthed the modern software industry. Like their peers of a decade before, the early Amiga developers were motivated more by love and passion than by money, and often operated more as a collective of friends and colleagues working toward a shared purpose than as competitors — i.e., as what Doug Carlston had once dubbed a “brotherhood” of software. Cinemaware became the breakout star of this group who committed themselves to the Amiga quickly and completely; that company was soon known to plenty of people who had never actually touched an Amiga for themselves. But there were plenty of others whose distinctly non-focus-group-tested names speak to their scruffy origins: companies like Aegis, Byte by Byte, and the one destined to be the great survivor of this pioneering era, NewTek. That NewTek would be just about the only one of these companies still in business in six or seven years does say something about the trajectory of the Amiga in North America, but perhaps says just as much about the nature of the companies themselves. Once again like their peers in the early 8-bit software industry, these early Amiga publishers carried along with their commitment to relentless innovation an often shocking ineptitude at executing fundamentals of running a business like writing marketing copy, keeping books, drawing up contracts, and paying taxes.

The story of our company of choice for today, MicroIllusions, is typical enough to almost stand in for that of the early Amiga software industry as a whole. At the same time, though, “typical” in this time of rampant innovation meant some extraordinarily original software. That’s particularly true of the works of MicroIllusions’s highest-profile programmer, David Joiner (or, as he was better known by his friends then and still today, “Talin,” his online handle). Joiner, who describes his view of the universe as of “some giant art project,” has dedicated his life to being “compulsively creative,” in both the digital and analog worlds. His vacuum-forming costumes, which transform him into alien space-bugs or knights in armor, have been the hit of many a science-fiction convention. He’s also an enthusiastic painter — “for a long time I thought my career was going to be in art” — as well as a musician and composer.

Joiner was first exposed to computers during the four years he spent at the end of the 1970s in the Air Force, programming the big mainframes of the Strategic Air Command in Omaha. He spent the several years following his discharge kicking around the margins of the burgeoning PC industry, writing amateur and semi-professional games for the Radio Shack Color Computer among other models and working briefly for DataSoft before they went bankrupt in the industry’s great mid-decade shakeout. That left him in the state in which a Los Angeles-area computer-store owner named Jim Steinert first met him: 27 years old, sleeping on friends’ couches, picking up contract programming work when he could get it, and spending much of the rest of his time hanging out at Steinert’s store — KJ Computer, located in the suburb of Granada Hills — drooling over their new Amigas.

The seeds of MicroIllusions were planted during one day’s idle conversation when Steinert complained to Joiner that, while the Amiga supposedly had speech synthesis built into its operating system, he had never actually heard his machines talk; in the first releases of AmigaOS, the ability was hidden within the operating system’s libraries, accessible only to programmers who knew how to make the right system calls. Seeing an interesting challenge, not to mention a chance to get more time in front of one of Steinert’s precious Amigas, Joiner said that he could easily write a program to make the Amiga talk for anyone. He proved as good as his word within a few hours. Impressed, Steinert asked if he could sell the new program in his store for a straight 50/50 split. Given his circumstances, Joiner was hardly in a position to quibble. When the program sold well, Steinert decided to get into Amiga software development in earnest with the help of his wunderkind.

He leased an office for his new venture MicroIllusions a few blocks from his store, and also picked up the lease on a small house to form a little software-development commune consisting of Joiner and three of his friends, talented artists and/or programmers all. Joiner describes the first year or two he spent creating inside that little house as “probably the best time of my life. We really felt like we were building the future.”

In these heady days when the Amiga was fondly imagined by its zealots as likely to become the new face of mainstream family-friendly computing, Steinert pushed Joiner to make as his first project an edutainment title similar to a Commodore 64 hit called Cave of the Word Wizard, in which the player must explore a cave whilst answering occasional spelling questions to proceed. Joiner’s response was Discovery, which replaced the cave with a spaceship and allowed for the creation of many additional data disks covering subjects from math to history to science to simple trivia for adult players. Setting a pattern that would hold for the remainder of his time with MicroIllusions, Joiner brought all his creative skills to bear on the one-man project, drawing all of the art himself in Deluxe Paint and also writing a music soundtrack in addition to the game’s code — and all in just four months. Because the Amiga would never quite conquer North America as Steinert had anticipated, the market for the Discovery line would always be a limited one, but it would prove a consistent if modest seller for MicroIllusions for years to come.

Having proved himself with Discovery, Joiner was allowed to embark on his dream project: a hybrid game — part action, part adventure, part CRPG — that would harness the Amiga’s capabilities in the service of something different from anything that had come before. He wanted to incorporate two key ideas, one involving the game’s fiction, the other its presentation. In the case of the former, he wanted to push past the oh-so-earnest high-fantasy pastiches typical of CRPG fictions in favor of something more whimsical, more Brothers Grimm than J.R.R. Tolkien. This territory was hardly completely unexplored in gaming — Roberta Williams in particular had built a career around her love of fairy tales — but it was unusual to see in a game that owed as much to action games and CRPGs as it did to the adventure games for which she was known. Joiner’s other big idea, meanwhile, really was something entirely new under the sun: he wanted to create a world that the player would traverse not in discrete steps or even screens but as a single scrolling, contiguous landscape of open-ended, real-time possibility.

The Faery Tale Adventure is the story of three brothers who set out to save their village of Tambry from an evil necromancer. Their quest will require one or more of them — if you get one of them killed, you automatically take the reins of another — to traverse the vast world of Holm from end to end, a process that by itself could take you the player hours of real time if journeying entirely on foot. Whilst traveling, you must also fight monsters and assemble the clues necessary to complete your quest.

It’s difficult to convey using words just how lovely and lyrical your journeys around Holm can be. Even screenshots don’t do The Faery Tale Adventure justice; this is a game that really must be seen and heard in action. Here, then, is just a little taste, in which I take a magical ride on the back of a giant turtle to visit a sorceress in her crystalline lair.

If it’s difficult to fully describe the experience of playing The Faery Tale Adventure using words, it’s doubly difficult to explain just how stunning it was in its day. Note the depth-giving isometric perspective, still a rarity in games of the mid-1980s. Note the way that characters and things cast subtle shadows. And note how the entirety of the world is presented at the same scale. Gone is the wilderness/town dichotomy of the Ultima games, in which the latter blow up from tiny spots on the map to self-contained worlds of their own when you step into them. In The Faery Tale Adventure, if it’s small (or big) on the outside, it’s small (or big) on the inside. I’d also tell you to note the wonderful music, except that I’m quite sure you already have (assuming you have the sound turned on, of course). Seldom has music made a game what it is to quite the extent it does this one.

Leaving aside the goal of actually solving the game, which is kind of hopeless — we’ll get to that in a moment — The Faery Tale Adventure is all about the rhythm of wandering, following roadways and peeking into hidden corners as the music plays and day turns to night and back again. Like another early Amiga landmark, Defender of the Crown, and unlike far too many other games on this platform and others, it has a textured aesthetic all its own that’s much more memorable than the bloody action-movie pyrotechnics so typical of games then and now. Play it just a little, and you’ll never, ever forget it.

That every bit of this vast world and all that makes it up — code, art, and music alike — was created virtually unaided by David Joiner in about seven months never ceases to amaze me. This Leonardo had found his niche at last:

It’s ironic because when I was growing up I was never able to focus on one single creative outlet and ignore the others — and this was considered a disadvantage. People would tell me that I had to learn to focus on one thing. Otherwise I would never be successful, just be a dilettante. I struggled to find a profession which would use all of my skills, not just some of them.

Still, stunning technical and aesthetic achievement that it is, there’s no denying that The Faery Tale Adventure is kind of a mess as a piece of game design. Its problems are all too typical of a game designed and implemented by a single idiosyncratic individual with, at best, limited external input. Some of the mechanical wonkiness I can live with. For instance, I’m not too bothered by the fact that, if you don’t get killed in one of the first few extremely difficult fights, you level up enough inside of an hour or so to the point that fighting becomes little more than a trivial annoyance for the rest of the game. The broken character-building aspect is forgivable in light of the fact that that doesn’t feel like what the game really wants to be about anyway. (That said, CRPG addicts should certainly approach this one with caution.)

But we can’t so easily wave aside the broken main spine of the game, the fact that it’s all but insoluble on its own terms. The Faery Tale Adventure presents itself as a breadcrumb-following game like the Ultimas, but its breadcrumbs are so scattered at some stages, so literally nonexistent at others, that it’s all but impossible to piece together where to go or what to do. After exploring Holm for a while, the charm of the music and the colorful graphics begins to fade and you begin to realize what a dismayingly empty place it really is. Almost every building is vacant, virtually every hotly anticipated new voyage of discovery proves ultimately underwhelming. Moments of wonder, like the first time you hitch a ride on that turtle you see above — or, even better, on a majestic swan — do crop up from time to time, but far too infrequently. The final impression is of nothing so much as a beautiful world running inside a marvelous engine that’s now just waiting for a designer to come along and, you know, write an actual game for it all. You can see contemporaneous reviewers struggling with this impression whilst giving the game the benefit of every possible doubt; The Faery Tale Adventure is nothing if not a game that makes you want to love it. Computer Gaming World‘s Roy Wagner, for instance, felt compelled to attach a rough walkthrough to try to make it actually playable to his very positive critical take on the game. Later, when the game was ported to the Sega Genesis, Sega found its design so intractable that they demanded that a similar walkthrough be included in the very manual. (One could wish that they had demanded that the design be properly fixed instead.) Joiner notes that his approach was to “start with a basic engine and then add detail like crazy,” which does rather sound like code for “write a game engine and then try to shoehorn an actual semblance of game in there at the last minute, when you realize your deadline is looming.”

Yet the fact remains that technical game-changers and audiovisual charmers like The Fairy Tale Adventure can usually get away with a multitude of design sins in the face of the gaming public’s insatiable appetite for the new. Knowing he had a potential hit on his hands, Steinert determined to make a veritable Electronic Arts-style rock star out of its creator. Joiner strapped himself into his knightly armor for an inadvertently hilarious photo shoot; the end results look tacky and painfully nerdy in exactly the way that the game itself doesn’t. But no matter: The Faery Tale Adventure became a hit on the Amiga after its release in early 1987 — just in time for a new influx of unabashed Amiga gamers in the form of new Amiga 500 owners — whereupon Steinert took advantage of his favored platform’s halo effect by selling less compelling ports for the Commodore 64 and MS-DOS and, years later, that rather more impressive Sega Genesis translation. The game’s success led to Activision signing MicroIllusions on as an “affiliated publisher,” a real shot at the big time.

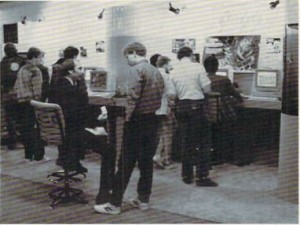

For better or for worse, though, Steinert just couldn’t bring himself to leave behind his scruffy roots in the Amiga hacking community. Games remained only one aspect of MicroIllusions, who also developed and published such only-Amiga-makes-it-possible software as Photon Paint, the first program to let one draw and edit pictures directly in the Amiga’s 4096-color HAM mode, and Cel Animator, a classical animation package crafted with the aid of Heidi Turnipseed, a veteran of Disney and Don Bluth Productions. The high-water point for MicroIllusions unsurprisingly corresponded with that of the Amiga itself in North America: 1988, when sales were trending upward and the big breakthrough seemed just around the corner. MicroIllusions was known during this period for their lavish trade-show displays — in truth, probably more lavish than they could realistically afford even then — that made them among the most prominent of the Amiga-centric software houses not named Cinemaware. That summer MicroIllusions products took up almost half of a Computer Chronicles television feature on the Amiga scene.

The MicroIllusions booth at the January 1988 AmiExpo show in Los Angeles, which filled half of one wall inside the Westin Bonaventure’s convention space.

David Joiner demonstrated his latest project-in-progress on-air on that program: Music-X, a MIDI music sequencer that he’d created largely out of concern that the hated Atari ST was getting ahead of the Amiga when it came to music software (never underestimate the motivation provided by good old platform jingoism). By the time that Music-X appeared at last to rave reviews at the tail end of 1989, MicroIllusions was already in dire straits, their phones perpetually coming on- and off-line and rumors swirling about their alleged demise. That situation would remain largely unchanged for another two desperate years. Their plight must to some extent be linked to that of the Amiga itself, which had failed to ever take off as Steinert had confidently expected when purchasing all that lavish trade-show floor space. It also didn’t help that, while they released a number of other modestly well-reviewed games, they never managed another transformative hit to come close to The Faery Tale Adventure. Thanks to that failure, Activision humiliatingly dropped them as an affiliated publisher barely a year after signing them up, citing the low sales of their latest games as just not making it worth anyone’s while anymore. Even an unexpected high-profile deal with Hanna-Barbera to produce games based on cartoon franchises like Scooby Doo, The Flintstones, and The Jetsons — truly a lifeline if ever there was one — collapsed amid allegations of breached contracts and botched schedules.

One suspects that the real cause behind these failures and so many others was a nemesis of MicroIllusions’s own making that also plagued many others in the Amiga’s home-grown software industry: a simple lack of business acumen, and with it an associated tendency to place dreams before ethics. Rather than belabor the point too much more personally, I’ll deliver David Joiner’s take on Jim Steinert’s idea of running a business:

My financial relationship with MicroIllusions was long and complicated. Jim wasn’t a good businessman. That was not unusual for the software industry at the time, but there was so much wide-open opportunity that any half-competent person could start a software business and be moderately successful.

Jim and I also differed in our approach to business ethics. He imagined himself to be a sharp dealer, and once boasted to me how he “saved money” in dealing with disk-duplication companies. You see, at the time there were companies which would do all the duplication work — that is, make copies of the floppy disks, print the packaging, and assemble the boxes. And many of these companies offered ninety-day terms — that is, you didn’t have to pay for ninety days, so you could use the money you made selling the product to pay back the duplicators. This made it possible to be an entrepreneur with very little startup capital, other than the sweat equity of writing software.

Well, Jim’s idea was that when the ninety days come up you simply refuse to pay — and then, eight months later when the duplicators eventually get around to suing you, you settle out of court for like one-third of the money. This same kind of playing fast and loose with the rules is what caused him to lose the Hasbro [sic. — I believe he means Hanna-Barbera] contract, which up to that point had been an incredibly valuable asset to the company.

Many years later, I went over all the royalty statements I had gotten from MicroIllusions, and discovered that there were lots of basic arithmetic errors in them — and not always in Jim’s favor.

The story of MicroIllusions is hardly unique among the companies we’ve encountered in this history, having much in common with that of many of the immediately preceding generation of software pioneers: companies like California Pacific, Muse, and Adventure International. Enthusiasm and programming talent can only make up for a lack of basic business acumen for so long. Despite it all, MicroIllusions somehow survived, at least nominally, through 1991, when their remaining assets, including The Faery Tale Adventure, were acquired by a new company called HollyWare who used the contracts they had purchased to launch a fruitless $10 million lawsuit against a now sorely ailing Activision for allegedly mishandling that old distribution deal. As an Amazing columnist wrote as the suit went into discovery, “The really interesting thing to discover is how MicroIllusions expects to get ten megabucks out of a company with a negative net worth.” HollyWare, needless to say, didn’t last very long.

By then Joiner had long since moved on to greener pastures in games and other forms of software development, although he would never again helm quite so impactful a project as The Faery Tale Adventure. The writing had been on the wall for software Leonardos even as he was creating his masterwork. Working with a new development team who called themselves The Dreamer’s Guild, he did belatedly create Halls of the Dead: The Faery Tale Adventure II in 1997. In the tradition of its predecessor, it looked and initially seemed to play great, but showed itself over time to be half-finished and well-nigh uncompleteable.

In the end, then, the business legacy of MicroIllusions is a bit of a tawdry one, one more example of a phenomenon that would always plague the Amiga: the platform seemed to attract idealists and shysters in equal numbers — and, somehow, often in the same individual. Yet it’s because its story is both so groundbreaking and so typical that the company makes such a worthwhile case study for anyone wishing to understand the oft-dirty life and times of the Amiga in its heyday. During MicroIllusion’s brief existence they produced some visionary software that, like so much else that came out of the Amiga scene, gave the world an imperfect glimpse of its multimedia future. That’s as true of Photon Paint, the progenitor of photographic-quality visual editors like PhotoShop, as it is of Music-X, a forerunner of easy-to-use music packages like GarageBand. And, most importantly for our purposes, it’s true of The Faery Tale Adventure, a rough draft of what games might come to be in the future. It’s a game that’s perhaps best appreciated in the context of its time, as I’m so able to do thanks to all of the research — okay, playing of old games — I do for this blog. It stands out so dramatically from its contemporaries that it gave me a catch in my throat when I first saw it again that wasn’t that different from the one I felt when I saw it for the first time back in 1987. That’s a feeling that may be hard for you to entirely duplicate if you’re not a really — I mean, really — dedicated reader who’s playing all these games right along with me. But no matter. If you have an hour or two to kill, give it a download, [1]The music at the beginning of the game is a distorted mess in this version, the only otherwise working one I could find. This is down to one of the few differences between the Amiga 1000, for which the game was originally designed, and later Amiga models — a sound pointer doesn’t get automatically set in the latter. If you just give it a moment, the music will resolve from dissonance to consonance and will play as it should henceforward. I think it’s kind of a cool effect, actually — but then I occasionally blast Sonic Youth, much to my wife’s chagrin, so take that with a grain of salt.

Note that you will need to answer a few copy-protection questions at the beginning by using the map included in the zip.

For those of you who are hopeless completionists, I’ve also included with this zip the Computer Gaming World review that gives much valuable guidance on how to pursue your (otherwise almost certainly futile) quest.

By far the easiest way to get started in Amiga emulation and to play this game and the other Amiga games I’ll be featuring in this blog for quite some time to come is by purchasing Cloanto’s Amiga Forever package. It makes the whole process pretty painless. fire up an Amiga emulator, and just have a little wander through Holm. Never did a bad game feel — and sound — so good.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of February 1988 and October 1991; Commodore Magazine of September 1989; Amazing Computing of August 1987, April 1988, June 1988, August 1989, October 1989, March 1990, April 1990, October 1991, December 1991, and April 1992; Info of April 1992. The home page of David Joiner (Talin) hasn’t been updated since 2000, but was nevertheless very useful. Still more useful was an interview with Joiner done by Amiga Lore.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The music at the beginning of the game is a distorted mess in this version, the only otherwise working one I could find. This is down to one of the few differences between the Amiga 1000, for which the game was originally designed, and later Amiga models — a sound pointer doesn’t get automatically set in the latter. If you just give it a moment, the music will resolve from dissonance to consonance and will play as it should henceforward. I think it’s kind of a cool effect, actually — but then I occasionally blast Sonic Youth, much to my wife’s chagrin, so take that with a grain of salt.

Note that you will need to answer a few copy-protection questions at the beginning by using the map included in the zip. For those of you who are hopeless completionists, I’ve also included with this zip the Computer Gaming World review that gives much valuable guidance on how to pursue your (otherwise almost certainly futile) quest. By far the easiest way to get started in Amiga emulation and to play this game and the other Amiga games I’ll be featuring in this blog for quite some time to come is by purchasing Cloanto’s Amiga Forever package. It makes the whole process pretty painless. |

|---|