In the years following Jack Tramiel’s departure, Commodore suffered from a severe leadership deficit. The succession of men who came and went from the company’s executive suites with dizzying regularity often meant well, were often likable enough in their way. Yet they were also weak-willed men who offered only timid, conventional ideas whilst living in perpetual terror of the real boss of the show, Commodore’s dilettantish chairman of the board and interfering largest stockholder Irving Gould.

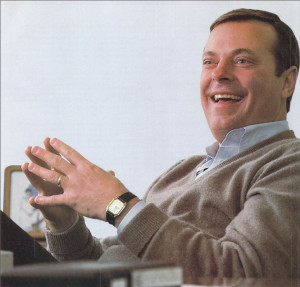

The exception that proves the rule of atrocious management is Thomas Rattigan, the man who during his brief tenure saved Commodore and in the process the Commodore Amiga from an early death. Rattigan wasn’t, mind you, a visionary; he never got the time to demonstrate such qualities even if he did happen to possess them. His wasn’t any great technical mind, nor was he an intrinsic fan of computers as an end unto themselves; in common with a rather distressing number of industry executives of the time, Rattigan, like Apple’s John Sculley a veteran of Pepsi Cola, seemed to take a perverse pride in his computer illiteracy, saying he “never got beyond the slide rule” and not even bothering to place a computer on his desk. He may not have even been a terribly nice guy; the thousands of employees he laid off, among them virtually the entire team that had once been Amiga, Incorporated, certainly aren’t likely to invite him to dinner anytime soon. No, Rattigan was simply competent, and carried along with that competence a certain courage of his own convictions. That was more than enough to make him stand out from his immediate predecessor and his many successors like the Beatles at a battle of the bands.

Rattigan was appointed President and Chief Operating Officer of Commodore International on December 2, 1985, and Chief Executive Officer on April 1, 1986, succeeding the feckless former steel executive Marshall Smith, whose own hapless tenure would serve as a blueprint for most of the Commodore leaders not named Rattigan who would follow. After replacing Tramiel in February of 1984, Smith had fiddled while Commodore burned, going from the billion-dollar face of home computing in North America to the business pages’ favorite source of schadenfreude, hemorrhaging money and living under the shadow of a gleeful deathwatch. The stock had dropped from almost $65 per share at the peak of Tramiel’s reign to less than $5 per share at the nadir of Smith’s. It was Rattigan, in one of his last acts before assuming the mantle of CEO as well as president, who negotiated the last-ditch $135 million loan package that gave Commodore — in other words, Rattigan himself — a lease on life of about one year to turn things around.

Some of the changes that Rattigan enacted to effect that turnaround were as inevitable as they were distressing: the waves of layoffs and cutbacks that had already begun under Smith’s reign continued for some time. Unlike Smith, however, Rattigan understood that he couldn’t cost-reduce Commodore back to profitablity.

The methods that Rattigan used to implement triage on the profit side of the ledger sheet were unsexy but surprisingly effective. One was entry into the burgeoning market for commodity-priced PC clones, hardware that could be thrown together quickly using off-the-shelf components and sold at a reasonable profit. Commodore’s line of PC clones would never do much of anything in North America — the nameplate was too associated with cheap, chirpy home computers for any corporate purchasing manager to glance at it twice — but it did do quite well in Europe; in some European countries, especially West Germany, the Commodore brand remained as respectable as any other.

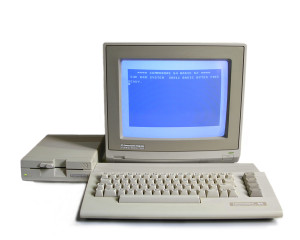

Rattigan’s other revenue-boosting move was even more simple and even more effective. Commodore’s engineers had been working on a new version of the 64. Dubbed internally the 64CR, for “Cost Reduced,” it was built around a redesigned circuit board that better integrated many of the chips and circuitry using the latest production processes, resulting in a substantial reduction in the cost of production. The chassis and case were also simplified — for example, to use only two instead of many different types of screws. While they were at it, Commodore dramatically changed the look of the machine and most of its common peripherals to match that of the newer Commodore 128, thus creating a uniform appearance across their 8-bit line. As Rattigan said, “I think you’ve got to give people the opportunity not to have a black monitor, a green CPU, and a red disk drive.”

All of which was very practical and commonsensical. Looking at the new machine, however, Rattigan saw an opportunity to do something Commodore had never done before: to raise its price, and thereby to recoup some desperately needed profit margin. This really was a revolutionary thought for Commodore. Ever since releasing their VIC-20 model that had created the home-computer segment in North America, Commodore had competed almost entirely on the basis of offering more machine for less money than the other folks — an approach that did much to create the low-rent image that would dog the brand for the rest of the company’s life. Commodore had always kept their profit margins razor thin in comparison to the rest of the industry, trusting that they would, as the old saying/joke goes, “make it up in volume.” Now, though, Rattigan realized that the 64 had much more than price alone going for it. Almost everyone buying a 64 in 1986 was motivated largely by the platform’s peerless selection of games. Most, he theorized, would be willing to pay a little more than what Commodore was currently charging to gain access to that library. Thus when Commodore announced the facelifted 64 — now rechristened simply the 64C for obvious reasons — they also announced a 20 percent bump in its wholesale price. To ease some of the pain, they would bundle with it something called GEOS, an independently developed graphically-oriented operating environment that claimed to turn the humble 64 into a mini-Macintosh. (It didn’t really, of course, but it was a noble, impressive effort for a machine with a 1 MHz 8-bit processor and 64 K of memory.) Anyone who’s been around manufacturing at all will understand just what a huge difference a price increase of that magnitude, combined with a substantial reduction in manufacturing cost, would mean to Commodore’s bottom line if customers did indeed prove willing to continue buying the new model in roughly the same numbers as the old. Thankfully, Rattigan’s instincts proved correct. The 64C picked up right where the older model had left off, a brisk — and vastly more profitable — seller.

Sometimes, then, the simplest fixes really are the most effective. Taken together with the cost-cutting, these two measures returned Commodore to modest profitability well before Rattigan’s one-year deadline expired. Entering 1987, the company looked to be in relatively good shape for the short term. Yet questions still swirled around its long-term future. If Commodore didn’t want to accept the depressing fate of becoming strictly a maker of PC clones for the European market, they needed a successful platform of their own that could become the successor to the 64, which was proving longer lived than anyone had ever predicted but couldn’t go on forever. That successor had to be the Amiga. And therein lay problems.

The Amiga was in a sadly moribund state by the beginning of 1987. The gala Lincoln Center debut was now eighteen months in the past, but it felt like an eternity. The excitement with which the press had first greeted the new machine had long since been replaced by narratives of failure and marketing ineptitude. Commodore had stopped production of the Amiga in mid-1986 after making just 140,000 machines, yet was still able to fill the trickle of new orders from warehouse stock. Sure, some pretty good games had been made for the Amiga, at least one of which was genuinely groundbreaking, but with numbers like those how long would that continue? Already Electronic Arts had quietly sidled away from their early declarations that together they and the Amiga would “revolutionize the home-computer industry,” turning their focus back to other, more plebeian platforms where they could actually sell enough games to make it worth their while. Ditto big players in business and productivity software like Borland, Ashton-Tate, and WordPerfect. The industry at large, it seemed, was just about ready to put a fork in Commodore’s erstwhile dream machine.

The Amiga’s most obvious failing was one of marketplace positioning. Really, just who was this machine for? There were two obvious markets: homes, where it would make the best games machine the world had yet seen; and the offices of creative professionals who could make use of its unprecedented multimedia capabilities. Yet the original Amiga model had managed to miss both targets in some fairly fundamental ways. Svelte and sexy as it was, it lacked the internal expansion slots and big power supply necessary to easily outfit it with the hard drives, memory expansions, accelerator cards, and genlocks demanded by the professionals. Meanwhile its price of almost $2000 for a reasonably complete, usable system was far too high for the home market that had so embraced the Commodore 64. Throw in horrid Commodore marketing that ignored both applications in favor of positioning the Amiga as some sort of challenger to the PC-clone business standard, and it was remarkable that the Amiga had sold as well as it had.

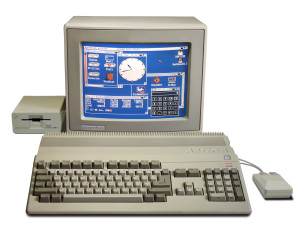

If there was a bright spot, it was that the Amiga’s obvious failing had an equally obvious solution: not one but two new models, each perfectly suited for — and, hopefully, marketed toward — one of its two logical customer bases. Rattigan, industry neophyte though he was, saw this reasoning as clearly as anyone, and pushed his engineers to deliver both new machines as quickly as possible. They were officially announced via a low-key, closed-door presentation to select members of the press at the January 1987 Winter Consumer Electronics Show. The two new models would entirely replace the original, which had always been officially called the Amiga 1000 but had seldom been referred to by that name heretofore. The Amiga 2000 would be the big, professional-level machine, with a full 1MB of memory standard — four times that of the 1000 — and all the slots and expansion possibilities a programmer, artist, or video-production specialist — or, for that matter, a game developer — could possibly want.

But it was the Amiga 500 that would become the most successful Amiga model ever released, as well as the heart of its legacy as a gaming platform. Designed primarily by George Robbins and Bob Welland at Commodore’s West Chester, Pennsylvania, headquarters — the slowly evaporating original Los Gatos Amiga team had little to do with either of the new models — the 500 was code-named “Rock Lobster” during development after the B-52’s song (reason enough to love it right there if you ask me). Key to the work was a re-engineering of Agnus, the most complex of the Amiga’s custom chips, to make it smaller, simpler, and cheaper to manufacture; the end result was known as “Fat Agnus.” That accomplished, Robbins and Welland managed to stuff the contents of the 1000’s case into an all-in-one design that looked like a bulbous, overgrown Commodore 128.

The Amiga 500 wasn’t, especially in contrast to the 1000, going to win any beauty contests, but it got the job done. There was a disk drive built into the side of the case, a “trap door” underneath to easily increase memory from the standard 512 K to 1 MB, and an expansion port in lieu of the Amiga 2000’s slots that let the user add peripherals the old-fashioned Commodore way, by daisy-chaining them across the desktop. Best of all, a usable system could be had for around $1000, still a stratum or two above the likes of a 64 or 128 but nowhere near so out of the reach of the enthusiastic gamer or home hacker as had been the first Amiga. Compromised in some ways though it may have been from an engineering standpoint, enough to prompt a chorus of criticism from the old Los Gatos Amigans, the Amiga 500 was a brilliant little machine from a strategic standpoint, the smartest single move the post-Tramiel Commodore would ever make outside of electing to buy Amiga, Incorporated, in the first place.

But unfortunately, this was still Irving Gould’s Commodore, a company that seldom failed to follow every good decision with several bad ones. Amiga circles and the trade press at large were buzzing with anticipation for the not-yet-released new models, which were justifiably expected to change everything, when word hit the business press on April 23 that Thomas Rattigan had been unceremoniously fired. Like the firing of Jack Tramiel three years before when things were going so very well, it made and makes little sense. Gould would later say that Rattigan had been fired for “disobeying the chairman of the board” — i.e., him — and for “gross disregard of his duties,” but refused to get any more specific. Insiders muttered that Rattigan’s chief sin was that of being too good at his job, that the good press his decisions had been receiving had left Gould jealous. Just a couple of weeks before Rattigan’s firing, Commodore’s official magazine had published a lengthy interview with him, complete with his photo on the cover. To this Gould was reported to have taken grave exception. Yet Rattigan hardly comes across as a prima donna or a self-aggrandizer therein. On the contrary, he sounds serious, thoughtful, grounded, and very candid, explicitly rejecting the role of “media celebrity” enjoyed by Apple’s John Sculley, his former colleague at Pepsi: “When you have lost something in the range of $270 million in five quarters, I don’t think it’s time to be a media celebrity. I think it’s time to get back to your knitting and figure out how you’re going to get the company making money.” Nor does he overstate the extent of Commodore’s turnaround, much less take full credit for it, characterizing it as “tremendous improvement, but not an acceptable performance.” It seems hard to believe that Gould could be petty enough to object to such an interview as this one. But at least one more piece of circumstantial evidence exists that he did: Commodore Magazine‘s longtime editor Diane LeBold was forced out of the company on Rattigan’s heels, along with other real or perceived Rattigan loyalists. It made for one hell of a way to run a company.

True to form of being less of a pushover than Gould’s other executive lapdogs, Rattigan soon filed suit against Commodore for $9 million, for terminating his five-year employment contract four years early for no good reason. Commodore promptly counter-sued for $24 million, the whole ugly episode overshadowing the actual arrival of the Amiga 500 and 2000 in stores. After some five years of court battles, Rattigan would finally be awarded his $9 million — yes, every bit of it — just at a time when everything was starting to go sideways for Commodore and they could least afford to pay him.

With Rattigan now out of the picture — Gould had had him escorted off the campus by security guards, no less — Gould announced that he would be taking personal charge of day-to-day operations, a move that filled no one at the company other than his hand-picked circle of sycophants with any joy. But then, for Gould day-to-day oversight meant something different than it did for most people. He continued to live the lifestyle of the jet-setting super-rich, traveling the world — reportedly largely to dodge taxes — and conducting business, to whatever extent he did, by phone. Thus Commodore was not only under a cloud of rumor and gossip at this critical moment when these two critical new machines were being introduced, but they were also leaderless, their executive wings gutted and reeling from Gould’s purge and their ostensible new master who knew where. There was, needless to say, not much in the way of concerted promotion or messaging as the months marched on toward Christmas 1987, the big test of the Amiga 500.

While it didn’t abjectly fail that test, it didn’t really skate through with honors either. On the one hand, Amigas were selling again, and in better numbers than ever before. The narrative of the Amiga as a flop that was soon to be an orphan began to fade, and companies like Electronic Arts began to return to the platform, if not always as a target for first-run games at least as a consistent target for ports. WordPerfect even ported their industry-standard word processor to the Amiga. But on the other hand, the Amiga certainly wasn’t going to become a household name like the 64 anytime soon at this rate. In addition to the nearly complete lack of Commodore advertising, distribution remained a huge problem. Many people who might have found the Amiga very interesting literally never knew it existed, never saw an advertisement and never saw it in a store. Jack Tramiel’s decision to dump the 64 into mass-market channels like Sears and Toys “R” Us had been a breaking of his own word and a flagrant betrayal of his loyal dealers from which Commodore’s reputation had never entirely recovered. Yet it had also been key to the machine’s success; the 64 was available absolutely everywhere during its heyday, an inescapable presence to tempt plenty of people who would never think to walk into a dedicated computer store. Now, though, having laboriously and with very mixed results struggled to rebuild the dealer network that Tramiel had demolished, Commodore refused to do the same with the Amiga 500, even after some of those dealers had started to whisper through back channels that, really, it might be okay to offer some 500s through the mass market in the name of increasing brand awareness and corralling some new users who would quite likely end up coming to them for further hardware, software, and support anyway. But it didn’t happen, not in 1987, 1988, or the bulk of 1989.

The Amiga thus came to occupy an odd position on the American computing scene of the late 1980s, not quite a failure but never quite a full-fledged success either. Always the bridesmaid, never the bride; the talented actor never quite able to find her breakout role; pick your metaphor. Commodore blundered along, going through more of Irving Gould’s sock-puppet executives in the process. Max Toy, unfortunately named in light of the image that Commodore was still trying to shake, took over in October of 1987, to be replaced by Harold Copperman in July of 1989. Meanwhile the two Amiga models settled fairly comfortably into their roles.

Video production became the 2000’s particular strong suit. Amigas were soon regular workhorses on television series like Amazing Stories, Max Headroom, Lingo; on films like Prince of Darkness, Not Quite Human, Into the Homeland; on lots of commercials. If most of this stuff wasn’t exactly the pinnacle of cinematic art, it was certainly more Hollywood work than any other consumer-grade PC was getting. More important, and more inspiring, were the 2000s that found homes in small local newsrooms, on cable-access shows, and in small one- or two-person video-production studios. Just as the Macintosh had helped to democratize the means of production on paper via desktop publishing, the Amiga was now doing the same for the medium of video, complete with a new buzzword for the age: “desktop video.”

The strong suit of the Amiga 500, of course, was games. At first blush, the Amiga might seem a hard sell to game publishers. Even in 1988, after the 500 and 2000 had had some time to turn things around for the platform, a hit Amiga game might sell only 20,000 copies; a major blockbuster by the platform’s terms, 50,000. The installed base still wasn’t big enough to support much bigger numbers than these. An only modestly successful MS-DOS game, by contrast, might sell 50,000 copies, while some titles had reportedly hit 500,000 copies on the Commodore 64 alone. Yet, despite the raw numbers, many publishers discovered that the Amiga carried with it a sort of halo effect. Everyone seriously into computer games knew which platform had the best graphics and sound, which platform had the best games, even if some were reluctant to admit it openly. Publishers found that an Amiga game down-ported to other platforms carried with it a certain cachet inherited from its original version. Cinemaware, the premiere Amiga game developer and later publisher in North America, used the Amiga’s halo effect to particularly good commercial effect. All of their big releases were born, bred, and released first on the Amiga. They found that it made good commercial sense to do so, even if they ultimately sold far more copies to MS-DOS and Commodore 64 owners. While it’s true that Cinemaware could never have survived if the Amiga had been the only platform for which they made games, neither could they have made a name for themselves in the first place if the Amiga versions of their games hadn’t existed. Some of the same triangulations held sway, albeit to a lesser extent, among other publishers.

All told, the last three years of the 1980s were, relatively speaking, the best the Amiga would ever enjoy in North America. By the end of that period, with the 64 at last fading into obsolescence, the Amiga could boast of being the number two platform, behind only MS-DOS, for computer games in North America — a distant second, granted, but second nevertheless — while Commodore stood as the number three maker of PCs in North America in terms of units sold, behind only IBM and Apple. And Commodore was actually making money for most of this period, which was by no means always such a sure thing in other periods. But perhaps more important than numbers and marketshare was the sense of optimism. Every month seemed to bring some breakthrough program or technology, while every Christmas brought the hope that this would be the one where the Amiga finally broke into the public consciousness in a big way. To continue to be an Amiga loyalist in later years would require one to embrace Murphy’s Law as a life’s creed if one didn’t want to be positively smothered under all of the constant disappointments and broken promises that could make the platform seem cursed by some malicious higher power. But in these early, innocent times everything still seemed so possible, if only there would come the right advertising campaign, the right change in management at Commodore, the right hardware improvements.

But, ah, Commodore’s management… there lay the rub, even during these good years. Amiga owners watched with concern and then alarm as Apple and the makers of MS-DOS machines alike steadily improved their offerings whilst Commodore did nothing. In 1987, Apple debuted the Macintosh II, their first color model, with a palette of millions of colors to the Amiga’s 4096 and a hot new 16 MHz 68020 CPU inside. Yes, it cost several times the price of even the professional-grade Amiga 2000, and yes, 68020 or no, the Amiga could still smoke it for many animation tasks thanks to its custom chips. But then, even Apple’s prices always came down over time, and everyone knew that their hardware would only continue to improve. That same year, IBM introduced their new PS/2 line, and with it the new VGA graphics standard with about 262,000 colors on offer. More caveats applied, as Amiga fans were all too quick to point out, but the fact remained that the competition was improving by leaps and bounds while Commodore remained wedded to the same core chipset that they had purchased back in 1984. The Amiga 1000 had been a generation ahead of anything else on the market at the time of its release, but, unfortunately, generations aren’t so long in the world of computers. Gould and his cronies seemed unconcerned about or, still more damningly, blissfully unaware of the competition that was beginning to match and surpass the Amiga in various ways. In 1989, IBM spent 10.9 percent of their gross revenue on R&D, Apple 6.7 percent. And Commodore? 1.7 percent. The one area where Commodore did rank among the biggest spenders in the industry was in executive compensation, particularly the salary of one Irving Gould.

For the 1989 Christmas season, Commodore launched what would prove to be their first and last major mainstream advertising campaign for the Amiga 500. The $20 million campaign featured television spots produced by no less leading lights than Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment and George Lucas’s Lucasfilm. The slogan was “Amiga: The Computer for the Creative Mind.” The most lavish of the spots featured cameos by a baffling grab bag of minor celebrities, including Tommy Lasorda, Tip O’Neill, the Pointer Sisters, Burt Bacharach, Little Richard, and astronauts Buzz Aldrin, Gordon Cooper, and Scott Carpenter. Commodore’s advertising agency announced confidently that 92 percent of Americans would see an Amiga commercial an average of twenty times during November and December. Commodore would even begin selling 500s through mass-market merchandisers at last, albeit in a limited way, going through Sears and Service Merchandise alone. The campaign was hyped in the Amiga press as a last all-out effort to make that ever-elusive big breakthrough in North America. Sure, it was something they really needed to have done back in 1987, when the 500 first debuted, but at least they were doing it now. That was something, right? Right? In the end, it proved a heartbreaker of the sort with which Amiga fans would grow all too familiar over the years to come: it had no appreciable effect whatsoever. And with that Commodore slipped out of the mainstream American consciousness along with the decade with which their computers would always be identified.

The next year the first of a new generation of unprecedentedly ambitious games arrived — games like Wing Commander, Ultima VI, Railroad Tycoon — that looked, sounded, and played better on MS-DOS machines than they did on Amigas, thanks to the ever-improving graphics cards, sound cards, and new 32-bit 80386 processors in those heretofore bland beige boxes. Cinemaware that same year released Wings, the last of their big Amiga showcases, and then quietly died. The Amiga’s halo effect was no more. Just like that, an era ended.

And yet… well, here’s where things get a little confusing. As the Amiga was drying up as a gaming platform in North America, it was in many ways just getting started in Europe, with most of the classics still to come. Let’s rewind and try to understand how this parallel history came to be.

Commodore had always been extremely strong in Europe, going all the way back to their days as a maker of calculators. Their first full-fledged computer, the PET, had been little more than a blip on the radar in North America in comparison to its competitors the Radio Shack TRS-80 and the Apple II, yet it had fostered a successful and respected line of business computers across the pond. Commodore’s most consistently strong markets then would also prove the strongest of their twilight years: Britain and, especially, West Germany. Both operations were granted much more autonomy than the North American operation, and were staffed by smart people who were much better at selling Commodore’s American computers than Commodore’s Americans were. Germans in particular developed a special affinity for the Commodore brand, one that was virtually free of the home-computer/business-computer dichotomy that Commodore twisted themselves into knots trying to navigate in the United States. In Germany a good home computer was simply a good home computer, and if the same company happened to offer a good business computer, well, that was fine too.

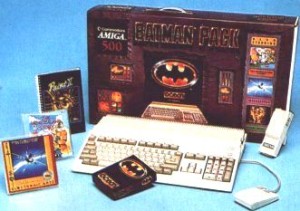

When Commodore’s European leadership looked to the new Amiga 500, they saw a machine sufficient to make the traditional videogame demographic of teenage boys, who were currently snatching up Commodore 64s and Sinclair Spectrums, positively salivate. They unapologetically marketed it on that basis. Knowing what their buyers really wanted the machine for, they quite early on took to bundling together special packages, usually just in time for Christmas, that combined a 500 with a few of the latest hot games. A particular home run was 1989’s so-called “Batman Pack,” which included the game based on the hit Batman movie, a fresh new arcade conversion called The New Zealand Story, the graphically stunning casual flight simulator F/A-18 Interceptor, and, since this was an Amiga after all, the platform’s signature application, Deluxe Paint II. Deluxe Paint aside, there was no talk of video production or productivity of any other stripe, no mention of the Amiga’s groundbreaking multitasking operating system, no navel-gazing discussions of the platform’s place in the multimedia zeitgeist. Teenage boys didn’t want any of that. What they wanted was great games with great graphics, and that’s exactly what Commodore’s European operations gave them. You were just buying a fun computer, a game machine, so you didn’t need to go through a dealer. From the beginning, the Amiga 500 was widely available at all of the glossy electronics stores on European High Streets. The West German operation went even further: they started selling Amigas through grocery stores. Buy an Amiga 500, hook it up to a television, pop in a disk, turn it on, and start playing.

The British and especially the Germans took to the Amiga 500 in numbers that Commodore’s North American executives could only dream of. By early 1988, Commodore could announce that they had sold 500,000 Amigas worldwide, a strong turnaround for a marque that had been all but left for dead a year before. A rather astonishing 200,000 of those machines, 40 percent of the total, had been sold in West Germany alone; Britain accounted for another 70,000. Even now, with the Christmas season behind them, Commodore West Germany was selling a steady 4000 Amiga 500s every week. A few months later came the simultaneously impressive and depressing news that the total market for Amiga hardware and software in West Germany (population 60 million) was now worth more than that for the United States (population 240 million). And where Germany led, the rest of Europe followed. Eighteen months later, with worldwide Amiga sales closing in on 1.5 million, it was the number one gaming computer in Europe, a position it would continue to enjoy for several years to come. Just about to begin its fade from prominence as a game machine in the United States, in Europe the Amiga’s best years and best games were still in front of it, as bedroom coders learned to coax performance out of the hardware of which its designers could hardly have conceived. The old Boing demo, once so stunning that crowds of trade-show attendees had peeked suspiciously under tables looking for the workstation-class machine that was really generating that animation, already looked singularly unimpressive. The story of the Amiga 500 in Europe was, in other words, the story of the Commodore 64 happening all over again. Commodore was now making the vast majority of their money in Europe, the North American operation a perpetual weak sister.

When journalists for the Amiga trade press in North America visited Europe, they were astounded. Here was the mainstream saturation that they had only been able to fantasize about back home. A report from a correspondent visiting a typical department store in Cologne must have read to American readers like a dispatch from Wonderland.

I came across a computerized book listing that was running on an Amiga 500. As I approached the computer department, I was greeted by a stack of Amiga 500s. I could not believe the assortment of Amiga titles on the book rack (hardcover ones, too!). I found two aisles full of Amiga software, consisting mostly of games. The Amiga selection was more than that of any other computer.

In a sense, it was just a reversion to the status quo. After all, prior to the introduction of the VIC-20 in 1981, Commodore’s income had been similarly unevenly distributed between the continents. Seen in this light, it’s the high times of the 1980s that are the anomaly, when American buyers flocked to the VIC-20 and the 64 and for a time made what had always been fundamentally a European brand — although, paradoxically, a European brand engineered and steered from the United States — into an intercontinental phenomenon. Not that that was of much comfort to the succession of executives who came and went from Irving Gould’s hotseat, fired one after another for their failure to make North American sales look as good as European sales.

But I did promise you 68000 Wars in the title of this article, didn’t I? So where, you might well be wondering, was the Amiga’s arch-rival the Atari ST in all this? Well, in North America it was a fairly negligible factor, although Atari would continue to sell their machine there almost as long as Commodore would the Amiga. The hype around the ST had dissipated quickly with the revelation in late 1986 that Atari really wasn’t selling anywhere near as many of them as Jack Tramiel liked to let on, and the Amiga 500, so obviously audiovisually superior and now much closer in price, soon proved a deadly foe indeed. The ST retained its small legion of loyal users: desktop publishers unwilling to splurge on a Macintosh, who took full advantage of its rock-solid monochrome high-resolution screen and Atari’s inexpensive laser printer, thereby truly making the ST live up to its old “Jackintosh” nickname; musicians, both amateur and professional, who loved its built-in MIDI port; programmers and hardware hackers who favored its simple, straightforward design over the Amiga’s more baroque approach; people who needed lots and lots of memory for one reason or another, on which terms Atari always offered the best deal in town (they released 2 MB and 4 MB ST models as early as 1987, when figures like that were all but inconceivable); inveterate Commodore haters and/or Atari lovers who bought it for the badge on its front. Still, there was little doubt which platform had won the 68000 Wars in North America. In the wake of the Amiga 500’s release, Atari began increasingly to turn to other ways of making money: buying the Federated chain of consumer-electronics stores; capitalizing on nostalgia for the glory days of the Atari VCS by continuing to sell both the old hardware and the cartridges to run on it; wresting away from Epyx a handheld gaming machine, the first of its kind, that was ironically designed by members of the old Amiga, Incorporated, team. When all else failed, there was always Jack Tramiel’s old hobby of lawsuits, of which he launched quite a few, most notably against the former owners of Federated for overstating their company’s value and against the new kid on the block in console gaming, Nintendo, for their alleged anti-competitive practices.

In Europe, the ST also came out second best to the Amiga, but the race was a much closer one for a while. Along with their love for all things Commodore, Germans found that they could also make room in their hearts for the Atari ST. It found a home in many German markets it never came close to cracking in the United States, being regarded as a perfectly respectable business computer there for quite some time. It also continued to do fairly well with gamers, thanks to Atari’s pricing strategies that always seemed to keep its low-end model just that little bit cheaper than the Amiga 500, enough to be a difference-maker for some buyers. When the Amiga became the biggest gaming computer in Europe, it was the Atari ST that slipped into the second spot. It would take the much more expensive MS-DOS machines some years yet to overtake these two 68000-based rivals. The economic chaos brought on by the reunification of West and East Germany, which caused many consumers there to tighten their wallets, only helped their cause, as did the millions of new price-conscious buyers who were suddenly scrambling for a piece of that Western computing action following the fall of the Iron Curtain.

The story of the Amiga, and to some extent also that of the ST, is often framed as a narrative of frustration, of brilliance that never got its due. There are some good reasons for that, but it can also be a myopic, America-centric view, ignoring as it does a veritable generation of youngsters on the other side of the Atlantic who grew up knowing these two platforms very well indeed. When I was writing my book about the Amiga, I couldn’t help but note the markedly different responses I got from friends in Europe and the United States when I told them about the project. Most Americans have no idea what an Amiga is (“Omega?”); most Europeans of a certain age remember it all too well, flashing me smiles redolent of nostalgia for afternoons spent before the television with their mates, when the summer seemed endless and the possibilities limitless. Instead of lamenting might-have-beens too much more, I expect to spend quite some articles over the next few years talking about the Amiga’s innovations and successes — and, yes, I’ll also have more to say about the Amiga’s perpetually overlooked little frenemy the Atari ST as well. Whether you grew up with one of these machines or you too aren’t quite sure yet what to make of this whole “Omega” thing, I hope you’ll stick around. Some amazing stuff is in store.

(Sources: Invaluable as always for these articles was Brian Bagnall’s book On the Edge: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Commodore. I can’t wait for the better, longer version. The long-running “Roomers” column in Amazing Computing is my go-to source for a month-by-month chronology of developments on the Amiga scene, and the source of most of the nit-picky factoids in this article. The issues of Amazing used include: March 1987, June 1987, July 1987, August 1987, October 1987, November 1987, December 1987, February 1988, April 1988, May 1988, June 1988, July 1988, August 1988, September 1988, November 1988, December 1988, January 1989, February 1989, March 1989, April 1989, May 1989, June 1989, July 1989, August 1989, September 1989, October 1989, November 1989, December 1989, January 1990, April 1990, May 1990, June 1990, February 1991, March 1991, April 1991, May 1991, December 1991. Commodore Magazine‘s fateful interview with Thomas Rattigan appeared in the May 1987 issue. Other sources include Retro Gamer 39 and of course my own book The Future Was Here. Hey, it’s not every day a writer gets to cite himself…)