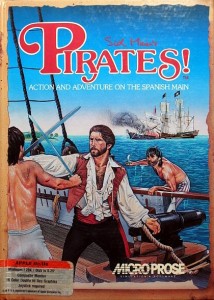

Shortly after designing and programming F-15 Strike Eagle and Silent Service, the two huge hits that made MicroProse’s reputation as the world’s premier maker of military simulations, Sid Meier took a rare vacation to the Caribbean. Accompanying him was his new girlfriend, whom he had met after his business partner Wild Bill Stealey hired her as one of MicroProse’s first employees. A few days after they left, she called Stealey in a panic: “I can’t find Sid!” It eventually transpired that, rather than being drowned or abducted by drug smugglers as she had suspected, he had gotten so fascinated with the many relics and museums chronicling the era of Caribbean buccaneering that he’d lost all track of time, not to mention the obligations of a boyfriend taking his girlfriend on a romantic getaway. She would just have to get used to Sid being a bit different from the norm if she hoped to stay together, Stealey explained after Meier finally resurfaced with visions of cutlasses and doubloons in his eyes. Meier had had a not-so-secret agenda in choosing this particular spot in the world for a romantic getaway. He was, you see, already working on his next game, a game about Caribbean piracy. The end result would be a dizzying leap away from military simulations into a purer form of game design — a leap that would provide the blueprint for his brilliant future career. If there’s something that we can legitimately label as a Sid Meier school of game design, it was for the game called simply Pirates! that it was first invented. As for the girlfriend, she apparently decided that she could indeed accept the vagaries of life with a game-design genius: she became his first wife.

Pirates! was first conceived by another MicroProse designer, Arnold Hendrick, as a fairly rigorous simulation of ship-to-ship combat in the Age of Sail, heavily inspired by the old Avalon Hill naval board game Wooden Ships and Iron Men. Such a game would have marked a bit of a departure for MicroProse, whose military simulations and strategy games had to date reached no further back into history than World War II, but would still broadly speaking fit in with their logo’s claim that they were makers of “Simulation Software.” Problem was, there were already computer games out there that claimed to scratch that itch, like SSI’s Broadsides and Avalon Hill’s own Clear for Action. While few outside the ultra-hardcore grognard set had found either of those games all that satisfying, Hendrick couldn’t seem to figure out how to do any better. And so Pirates! found itself on the back burner, and Hendrick moved on to do Gunship instead.

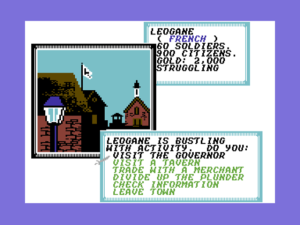

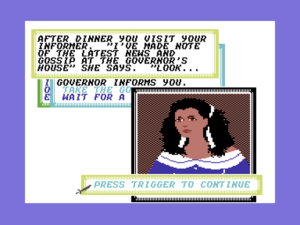

Sid Meier was inspired to pick up Hendrick’s idea of a pirate game by a seemingly innocuous bit of technological plumbing developed by Gregg Tavares, a MicroProse programmer who specialized in user interfaces and the decorative graphics and menus that went around the heart of their simulations. Like programmers at many other companies around this time, Tavares had developed what amounted to a very simplistic windowing engine for the Commodore 64, allowing one to wrap text messages or menus or graphics into windows and place them in arbitrary spots on the screen quickly and easily. “We had this way of bringing the game to life in a series of pictures and text, almost like a literary-ish — for the time — approach,” Meier says. It started him thinking in terms for which MicroProse was not exactly renowned: in terms of storytelling, in terms of adventure.

With the idea starting to come together at last, Meier soon declared Pirates! to be his official next project. In contrast to the large (by 1986 standards) team that was still busy with Gunship, the original Commodore 64 Pirates! would be created by a team of just 2.5: Meier as designer and sole programmer and Michael Haire as artist, with Arnold Hendrick coming aboard a bit later to do a lot of historical research and help with other design aspects of the game (thus returning a number of huge favors that Meier had done his own Gunship project). Meier, never a fan of design documents or elaborate project planning, worked as he still largely works to this day, by programming iteration after iteration, keeping what worked and cutting what didn’t to make room for other ideas. By project’s end, he would estimate that he had cut as much code from the game as was still present in the finished version.

Stealey was, to say the least, ambivalent about the project. “I said to Bill, ‘I’m going to work on this game about pirates,'” says Meier. “And he said, ‘Pirates? Wait a minute, there are no airplanes in pirates. Wait a minute, you can’t do that.’ And I said, ‘Well, I think it’s going to be a cool game.'” Stealey’s disapproval was an obvious result of his personal fixation on all things modern military, but there were also legitimate reasons to be concerned from the standpoint of image and marketing. He had worked long and hard to establish MicroProse as the leader in military simulations, and now Meier wanted to peel away, using time and resources on this entirely new thing that risked diluting his brand. Even a less gung-ho character might have balked. But, as Stealey had had ample opportunity to learn by now, the shy, mild-mannered Meier could be astonishingly stubborn when it came to his work. If he said he was doing a pirates game next, then, well, he was going to do a pirates game. Stealey could only relish the small victories — he had only recently convinced Meier at last to give up his beloved but commercially moribund Atari 8-bit machines and start developing on the Commodore 64 — and hope for the best.

Pirates! represented more than just a shift in subject matter. It introduced an entirely new approach to game design on Meier’s part, amounting to a radical rejection of the status quo at MicroProse. Fred Schmidt, MicroProse’s director of marketing at the time, described the company’s standard research-first approach to design thus in a 1987 interview:

We do nothing but research on a subject before we begin a project. We spend time in the library, with military personnel, with Major Stealey (U.S.A.F. Reserve) and his contacts to really find out what a subject is all about. We try to take all that information and digest it before we begin to design a game.

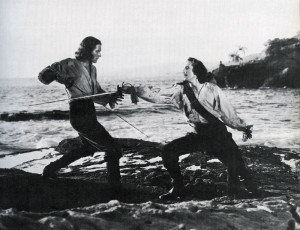

But Pirates! would be a very, very different sort of proposition. As Meier has often admitted in the years since, its design is based largely on his memories of the old Errol Flynn pirate movies he’d loved as a kid, refreshed by — and this must have really horrified Stealey — children’s picture books. Those, says Meier today with a sheepish look, “would really highlight the common currency” of the topic: “What are the cool things? That would give us some visual ideas, but also tell us what to highlight in the game.” “The player shouldn’t have to read the same books the designer has read in order to play,” he notes in another interview. Indeed, piracy is a classic Sid Meier topic in that everyone has some conception of the subject, some knowledge that they bring with them to the game. Far from undercutting swashbuckling fantasies with the grim realities of scurvy and the horrors of rape and pillage, Pirates! revels in a romanticized past that never actually existed. Most of its elements could be the result of a game of free-association played with the word itself in the broadest of pop-culture strokes: “There’s gotta be swordfighting, there’s gotta be ship battles, there’s gotta be traveling around the Caribbean, and the evil Spaniard guy.”

Meier and his colleagues at MicroProse derisively referred to adventure games — a term which in the mid-1980s still largely meant parser-driven text adventures — as “pick up the stick” games, noting that for all their promises of fantastic adventure they were awfully fixated on the fiddly mundanities of what the player was carrying, where she was standing, and how much fuel was left in her lantern. Theirs wasn’t perhaps an entirely fair characterization of the state of the art in interactive fiction by 1985 or 1986, but it was true that even most of the much-vaunted works of Infocom didn’t ultimately offer all that much real story in comparison to a novel or a film. If Meier was going to do an adventure game, he wanted to do something much more wide-angle, something with the feel of the pirate movies he’d watched as a kid. In fact, the idea of Pirates! as an “interactive movie” became something of a bedrock for the whole project, odd as that sounds today after the term has been hopelessly debased by the many minimally interactive productions to bear the label during the 1990s. At the time, it was a handy shorthand for the way that Meier wanted Pirates! to be more dramatic than other adventure games. Instead of keeping track of your inventory and mapping a grid of rooms on graph paper he wanted you to be romancing governors’ daughters and plotting which Spanish town to raid next. You would, as he later put it, be allowed to focus on the “interesting things.” You’d go “from one scene to the next quickly, and you didn’t have to walk through the maze and pick up every stick along the way.”

Allowing the player to only worry about the “interesting things” meant that the decisions the player would be making would necessarily be plot-altering ones. Therefore a typical fixed adventure-game narrative just wouldn’t do. What Meier was envisioning was nothing less than a complete inversion of a typical adventure game’s narrative structure. In an Infocom interactive fiction, the author has made the big decisions, mapping out the necessary beginning and end of the story and the high points in between, leaving the player to make the small decisions, to deal with the logistics, if you will, of navigating the pre-set plot. As the previous contents of this blog amply illustrate, I think the latter approach can be much more compelling than it sounds from the description I’ve just given it. I think the interactivity adds an experiential quality to the narrative that can make this type of approach, done right, a far more immersive and potentially affecting experience than a traditional static narrative. However, I also think there’s something to be said for the approach that Meier opted for in Pirates!: to have the player make the big decisions about the direction the story goes, and let the game make — or abstract away — all of the small decisions. Put another way, Pirates! should let you write your own story, a story you would own after it was complete. To return to the movie metaphor, you should indeed be the star. “You could go wherever you wanted to and you were clearly the central character in the story and you could take it wherever you wanted to go,” says Meier.

What would a pirate story be without a treasure map? “X” — or in this case a chest icon — marks the spot!

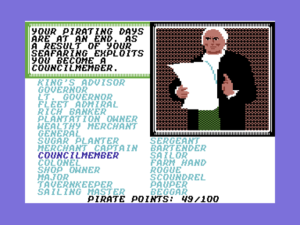

But how to offer that freedom? One key was, paradoxically, to limit the player’s options. When one is not in one of its action-oriented sub-games, Pirates! is entirely menu-driven, resulting in an experience simultaneously more accessible and more limiting than the parser’s cryptically blinking cursor with its admittedly unfulfillable promise of limitless interactive possibility. With his menus filled only with appropriately piratey choices, Meier could fill his game, not with stories per se, but with story possibilities drawn from the rich heritage of romanticized maritime adventure. Dodgy characters who hang out in the bars will occasionally offer to sell you pieces of treasure maps; evil Spaniards have enslaved four of your family members, and it’s up to you to track them down by following a trail of clues; the Spanish Silver Train and Treasure Fleet move across the map each year carrying fortunes in gold and silver, just waiting to be pounced on and captured. There are obvious limits to Pirates!‘s approach — you certainly aren’t going to get a narrative of any real complexity or depth out of this engine — but having the freedom to write your own story, even a shallow one, can nevertheless feel exhilarating. With no deterministic victory conditions, you can become just what you like in Pirates! within the bounds of its piratey world: loyal privateer aiding your nation in its wars, bloodthirsty equal-opportunity scoundrel, peaceful trader just trying to get by and stay alive (granted, this option can be a bit boring).

Which isn’t to say that there’s no real history in Pirates!. Once the design was far along, Arnold Hendrick came aboard to become a sort of research assistant and, one senses, an advocate for including as much of reality as possible in the game. It was Hendrick who convinced Meier to go against the grain of basing his game on the legends of piracy rather than the realities in at least a few respects. For instance, Pirates! takes place in the Caribbean between, depending on the historical period chosen, 1560 and 1680, thus forgoing the possibility of meeting some of the most famous names associated with piracy in the popular imagination: names like Edward Teach (the infamous Blackbeard), William Kidd, Jean Lafitte. The eventual 80-page manual, largely the work of Hendrick and itself something of a classic of the golden age of game manuals with its extensive and fascinating descriptions of the history of Caribbean piracy, dismisses pirates like Teach as unworthy of attention.

Those men were psychotic remnants of a great age, criminals who wouldn’t give up. They were killed in battle or hung for evils no European nation condoned. There was no political intrigue or golden future to their lives, just a bullet or a short rope. We found them unattractive and uninteresting compared to the famous sea hawks and buccaneers that preceded them.

That’s perhaps laying it on a bit thick — those getting raped and pillaged by the “sea hawks” might beg to differ with the characterization of their era as a “great age” — but the historical texture Hendrick brought added much to the game. Amongst other things, Hendrick researched the six different starting years available for free-form play, each with their own personality; designed six shorter historical scenarios based on famous expeditions and battles; researched the characteristics of the nine different vessels available to fight and sail, including the dramatic differences in the sailing characteristics of square-rigged versus fore-and-aft-rigged ships. And then there was the appropriately weathered-looking cloth map of the Caribbean that shipped in the game’s box and that was faithfully recreated in the game proper. MicroProse would hear from many a schoolchild in the years to come who had amazed her teacher with her knowledge of Caribbean geography thanks to Pirates!.

At the same time, though, Meier held Hendrick’s appetite for historical reality on a tight leash, and therein lies much of the finished game’s timeless appeal. We can see his prioritization of fun above all other considerations, a touchstone of his long career still to come, in full flower for the first time in Pirates!. Over the years I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve described a number of examples of systems that ended up being more interesting and more fun for their programmers to tinker with than for their players: think for instance of the overextended dynamic simulationism of The Hobbit or the Magnetic Scrolls text adventures. Pirates!, whose open dynamic world made for a fascinating plaything in its own right for any programmer, could easily have gone down the same path, but Meier had the discipline to always choose player fun over realism. “We could totally overwhelm the player if we tossed everything into the game, so it’s a question of selecting,” he says. “What are the most fun aspects of this topic? How can we present it in a way that the player feels that they’re in control, they understand what’s happening?”

In a 2010 speech, Meier made a compelling argument that early flight simulators such as the ones from MicroProse on which he’d cut his teeth managed to be as relatively straightforward and entertaining as they were as an ironic byproduct of the sharply limited hardware on which they had to run. When more powerful machines started allowing designers to layer on more complexity, everything started to go awry.

One of the things we pretend as designers is that the player is good. You’re really good! That’s kind of a mantra from us. We want the player to feel good about the play experience and themselves as they’re playing.

One example of where this perhaps went off the tracks is the history of flight simulators, going back a number of years. Early on they were easy to play, very accessible. You’d shoot down a lot of planes, have a lot of fun. But then we got to where every succeeding iteration of flight simulators became a little more realistic, a little more complex, a little more of a “simulation.” Pretty soon the player went from “I’m good!” to “I’m not good! I’m confused! My plane is on fire! I’m falling out of the sky!” The fun went out of them.

We have to be aware that it’s all about the player. The player is the star of the game. Their experience is what’s key. Keeping them feeling good about themselves is an important part of the experience we provide.

Notably, Meier abandoned flight simulators just as vastly more powerful MS-DOS-based machines began to replace the humble Commodore 64 as the premier gaming computers in North America. Still more notably for our purposes, Pirates! is an astonishingly forgiving game by the standards of its time. It’s impossible to really lose at Pirates!. If you’re defeated in battle, for instance, you’re merely captured and eventually ransomed and returned to your pirating career. This, suffice to say, is one of the most ahistorical of all its aspects; historical pirates weren’t exactly known for their long life expectancies. Pirates!‘s approach of using the stuff of history to inform but not to dictate its rules, of capturing the spirit of a popular historical milieu rather than obsessing over its every detail, wasn’t precisely new even at the time of its development. There are particular parallels to be drawn with Canadian developer Artech’s work for Accolade on what designer Michael Bate called “aesthetic simulations”: games like Ace of Aces, Apollo 18, and The Train. Still, Pirates! did it ridiculously well, serving in this sense as in so many others as a template for Meier’s future career.

Pirates! in general so successfully implements Meier’s player-centric, fun-centric philosophy that the few places where it breaks down a bit can serve as the exceptions that prove the rule. He admits today that its relatively strict simulation of the prevailing air currents in the region that can often make sailing east an exercise in frustration, especially at the higher of the game’s four difficulty levels, is arguably going somewhat too far out on the limb of realism. But most disappointing is the game’s handling of women, who exist in its world as nothing more than chattel; collecting more treasure and honors gives you better chances with better looking chicks, and marrying a hotter chick gives you more points when the final tally of your career is taken at game’s end. It would have been damnably difficult given the hardware constraints of the Commodore 64, but one could still wish that Meier had seen fit to let you play a swashbuckling female pirate; it’s not as if the game doesn’t already depart from historical reality in a thousand ways. As it stands, it’s yet one more way in which the games industry of the 1980s subtly but emphatically told women that games were not for them. (Much less forgivable from this perspective is Meier’s 2004 remake, which still persists in seeing women only as potential mates and dancing partners.) Despite it all, MicroProse claimed after Pirates!‘s release that it was by far the game of theirs with the most appeal to female purchasers — not really a surprise, I suppose, given the hardcore military simulations that were their usual bread and butter.

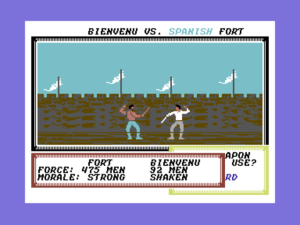

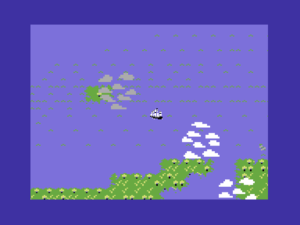

Pirates! is a famously difficult game to pigeonhole. There’s a fair amount of high-level strategic decision-making involved in managing your fleet and your alliances, choosing your next targets and objectives, planning your journeys, keeping your crew fed and happy. When the rubber meets the road, however, you’re cast into simple but entertaining action games: one-on-one fencing, ship-against-ship or ship-against-shore battling, a more infrequent — thankfully, as it’s not all that satisfying — proto-real-time-strategy game of land combat. And yet the whole experience is bound together with the first-person perspective and the you-are-there, embodied approach of an adventure game. Small wonder that MicroProse, who weren’t quite sure what to do with the game in marketing terms anyway, gave it on the back of the box the mouthful of a label of “action-adventure simulation.” It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, does it?

The adventure elements in particular can make Pirates! seem like something of an anomaly in the catalog of Sid Meier, generally regarded as he is as the king of turn-based grand-strategy gaming. In reality, though, he’s much less a slave to that genre than is generally acknowledged. Pirates!‘s genre-blending is very much consistent with another design philosophy he has hewed to to this day, that of prioritizing topic over genre.

I find it dangerous to think in terms of genre first and then topic. Like, say, “I want to do a real-time-strategy game. Okay. What’s a cool topic?'” I think, for me at least, it’s more interesting to say, “I want to do a game about railroads. Okay, now what’s the most interesting way to bring that to life? Is it in real-time, or turn-based, or is it first-person…” To first figure out what your topic is and then find interesting ways and an appropriate genre to bring it to life as opposed to coming the other way around and saying, “Okay, I want to do a first-person shooter; what hasn’t been done yet?” If you approach it from a genre point of view, you’re basically saying, “I’m trying to fit into a mold.” And I think most of the really great games have not started from that point of view. They first started with the idea that “Here’s a really cool topic. And by the way it would probably work really well as a real-time strategy game with a little bit of this in it.”

I think a good example of this is Pirates!. The idea was to do a pirate game, and then it was “Okay, there’s not really a genre out there that fits what I think is cool about pirates. The pirate movie, with the sailing, the sword fighting, the stopping in different towns, and all that kind of stuff, really doesn’t fit into a genre.” So we picked and chose different pieces of different things like a sailing sequence in real-time and a menu-based adventuring system for going into town, and then a sword fight in an action sequence. So we picked different styles for the different parts of the game as we thought were appropriate, as opposed to saying, “We’re going to do a game that’s real-time, or turn-based, or first-person, or whatever,” and then make the pirates idea fit into that.

This approach to design was actually quite common in the 1980s. See for example the games of Cinemaware, who consistently used radically different formal approaches from game to game, choosing whatever seemed most appropriate for evoking the desired cinematic experience. As game genres and player expectations of same have calcified over the years since, this topic-first — or, perhaps better said, experience-first — approach to design has fallen sadly out of fashion, at least in the world of big-budget AAA productions. Mainstream games today are better in many ways than they were in the 1980s, but this is not one of them. Certainly it would be very difficult to get an ambitious cross-genre experience like Pirates! funded by a publisher today. Even Meier himself today seems a bit shocked at his “fearlessness” in conjuring up such a unique, uncategorizable game. In addition to sheer youthful chutzpah, he points to the limitations of the Commodore 64 as a counter-intuitive enabler of his design imagination. Because its graphics and sound were so limited in contrast to the platforms of today, it was easier to prototype ideas and then throw them away if they didn’t work, easier in general to concentrate on the game underneath the surface presentation. This is something of a wistfully recurring theme amongst working designers today who got their start in the old days.

Pirates! was not, of course, immaculately conceived from whole cloth. Its most obvious gaming influence, oft-cited by Meier himself, is Danielle Bunten Berry’s Seven Cities of Gold, a design and a designer whom he greatly admired. There’s much of Seven Cities of Gold in Pirates!, at both the conceptual level of its being an accessible, not-too-taxing take on real history and the nuts and bolts of many of its mechanical choices, like its menu-driven controls and its interface for moving around its map of the Caribbean both on ship and on foot. Perhaps the most important similarity of all is the way that both games create believable living worlds that can be altered by your own actions as well as by vagaries of politics and economy over which you have no control: territories change hands, prices fluctuate, empires wax and wane. I would argue, though, that in giving you more concrete goals to strive for and a much greater variety of experiences Pirates! manages to be a much better game than its inspiration; Seven Cities of Gold often feels to me like a great game engine looking for something to really do. Both games are all about the journey — there’s no explicitly defined way to win or lose either of them, another significant similarity — but in Pirates! that journey is somehow much more satisfying. The extra layers of story and characterization it provides, relatively minimal though they still are, make a huge difference, at least for this player.

After you retire, you’re ranked based on your accomplishments and the amount of wealth you’ve accrued. This is as close as you can come to winning or losing at Pirates!.

Just about all of the other elements in Pirates!, from the trading economy to the sword-fighting, had also been seen in other games before. What was unusual was to build so many of them into one game and, most importantly, to have them all somehow harmonize rather than clash with one another. Meier himself is somewhat at pains to explain exactly why Pirates! just seemed to work so well. A few years after Pirates! he attempted a similar cross-genre exercise, a spy game that combined action and strategy called Covert Action. He himself judged the end result of that effort to have been much less successful. It seemed that, while the various elements played well enough on their own, they felt disconnected in the context of the whole, like two or more games rudely crammed together: “You would have this mystery you were trying to solve, then you would be facing this action sequence, and you’d do this cool action thing, and you’d get out of the building, and you’d say, ‘What was the mystery I was trying to solve?'” Pirates! was charmed in contrast; its various elements seem to fortuitously just work together. Meier has since theorized that this may be because all of its individual elements, taken in isolation, are quite simple — one might even say simplistic. But when blended together they turn out to be a perfect mixture of easily digestible experiences that never last long enough to lose the overall plot, a classic example of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

I’d be remiss not to also briefly mention just what a little technical marvel Pirates! is in its original Commodore 64 incarnation. It’s all too easy to overlook Sid Meier the brilliant programmer when thinking about Sid Meier the brilliant game designer. Yet it’s as much a credit to the former as the latter that the Commodore 64 Pirates! remains amazingly playable to this day. The disk loads are snappy enough to barely be noticeable; the fonts and graphics are bright and atmospheric; the occasional music stings are well-chosen; the various action games play fast and clean; the windowing system that got this whole ball rolling in the first place does its job perfectly, conveying lots of information elegantly on what is by modern standards an absurdly low-resolution display. And of course behind it all is that living world that, if not quite complex by the standards of today, certainly is by the standards of a 64 K 8-bit computer. While I’ve placed a lot of emphasis in my other recent articles on how far Commodore 64 graphics and sound had come by 1987, Pirates! is a far better work of pure game design than any I’ve talked about so far in this little series, worthy of attention for far more than its polished appearance or its important place in history, even if it is well-possessed of both. In fact, I’d go so far as to call it the greatest game ever born on the little breadbox, the peak title of the Commodore 64’s peak year.

Once Pirates! was ready in the spring of 1987 there was still the matter of trying to sell it. Director of marketing Schmidt was clearly uncertain about the game when Commodore Magazine interviewed him just before its release. Indeed, he was almost dismissive. “It takes us into territory MicroProse has never gone before,” he declared, accurately enough. “It is a combination text, graphic, simulation, action game.” (More of those pesky genre difficulties!) But then he was eager to move on to the firmer ground of Meier’s next project of Red Storm Rising, a modern-day submarine simulation based on Tom Clancy’s bestselling technothriller that was about as firmly in MicroProse’s traditional wheelhouse as it was possible for a game to be. As that project would indicate, Meier didn’t immediately abandon his old role of Wild Bill’s simulation genius to fully embrace the purer approach to game design that had marked the Pirates! project, not even after Pirates! defied all of Stealey and Schmidt’s misgivings to become MicroProse’s blockbuster of 1987, joining 1984’s F-15 Strike Eagle, 1985’s Silent Service, and 1986’s Gunship in a lineup that now constituted one of the most reliable moneyspinners in computer gaming; all four titles would continue to sell at a healthy clip for years to come. One suspects that Meier, still feeling his way a bit as a designer in spite of his successes, did Red Storm Rising and the game that would follow it, another flight simulator called F-19 Stealth Fighter, almost as comfort food, and perhaps as a thank you to Stealey for ultimately if begrudgingly supporting his vision for Pirates!. That, however, would be that for Sid Meier the military-simulation designer; too many other, bolder ideas were brewing inside that head of his.

There’s just one more part of the Pirates! story to tell, maybe the strangest part of all: the story of how the introverted, unassuming Sid Meier became a brand name, the most recognizable game designer on the planet. Ironically, it all stemmed from Stealey’s uncertainty about how to sell Pirates!. The seed of the idea was planted in Stealey by someone who had a little experience with star power himself: comedian, actor, and noted computer-game obsessive Robin Williams. Stealey was sitting at the same table as Williams at a Software Publishers Association dinner when the latter mused that it was strange that the world was full of athletic stars and movie stars and rock stars but had no software stars. A light bulb went on for Stealey: “We’ll make Sid a famous software star.” It wasn’t exactly a new idea — Trip Hawkins, for one, had been plugging his “electronic artists” for years by that point with somewhat mixed results — but by happenstance or aptitude or sheer right-place/right-time Stealey would pull it off with more success than just about anyone before or since. When the shy Meier was dubious, Stealey allegedly gave him a live demonstration of the power of stardom:

I had my wife, he had his girlfriend, and we’re sitting at dinner at a little restaurant. I said, “Sid, watch this. I’ll show you what marketing can do for you.” I went over to the maître d’ and I said, “Sir, my client doesn’t want to be disturbed.” He said, “Your client, who’s that?” I said, “It’s the famous Sid Meier. He’s a famous author. Please don’t let anybody bother us at dinner.” Before we got out of there, he had given 20 autographs. You know, we were a small company. You do whatever you can do to get a little attention, right?

As with many of Stealey’s more colorful anecdotes, I’m not sure whether we can take that story completely at face value. We are, however, on firmer ground in noting that when Pirates! made its public debut shortly thereafter it bore that little prefix that in later years would come to mark a veritable genre onto itself in many people’s eyes: the game’s full name was Sid Meier’s Pirates!. Gaming has generally been anything but a star-driven industry, but for some reason, just this one time, this bit of inspired star-making actually worked. Today Sid Meier’s name can be found tacked onto the beginning of a truly bewildering number of titles, including quite a few with which he had virtually nothing to do. The supreme irony is that this should have happened to one of the nicest, most unassuming, most humble souls in an industry replete with plenty of big egos that would kill for the sort of fame that just kind of walked up to Meier one day and sat down beside him while he hacked away obliviously in front of his computer. Not that it’s undeserved; if we’re to have a cult of personality, we might as well put a genius at its center.

Like Meier’s new approach to design, it wasn’t initially clear whether the “Sid Meier’s” prefix was destined to really become a long-term thing at all; Stealey judged the names and topics of Red Storm Rising and F-19 Stealth Fighter strong enough stand on their own. But then old Sid went off the military-simulation reservation and started to get crazy innovative again, and Stealey faced the same old questions about how to sell his stuff, and… but now we’re getting ahead of the story, aren’t we?

(Paper Sources: Gamers at Work by Morgan Ramsay; Game Design: Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; Computer Gaming World of November 1987; Commodore Magazine of September 1987; Retro Gamer 38, 57, and 82; Game Developer of February 2002, October 2007, January 2009, November 2010, and February 2013.

Online sources: Metro’s interview with Meier; Adam Sessler’s interview with Meier; Meier playing the 2004 Pirates! on IGN; Meier’s 2010 GDC keynote; Matt Chat 78.

You can download from this site disk images of the Commodore 64 Pirates! that Meier himself still considers the “definitive” version of the original game. Note, however, that this zip doesn’t include the essential manual and map. You can get them by buying Pirates! Gold Plus from GOG.com. Trust me, it’s worth it.)