Change was in the air as the 1980s began, the drawn-out 1960s hangover that had been the 1970s giving way to the Reagan Revolution. The closing of Studio 54 and the release of Can’t Stop the Music, the movie that inspired John J.B. Wilson to start the Razzies, marked the end of disco decadence. John Lennon, whilst pontificating in interviews on the joys of baking bread, released an album milquetoast enough to play alongside Christopher Cross and Neil Diamond on Adult Contemporary stations — prior to getting shot, that is, thus providing a more definite punctuation mark on the end of 1960s radicalism. Another counterculture icon, Jerry Rubin, was left to give voice to the transformation in worldview that so many of his less famous contemporaries were also undergoing. This man who had attempted to enter a pig into the 1968 Presidential election in the name of activist “guerrilla theater” became a stockbroker on the same Wall Street where he had once led protests. “Money and financial interest will capture the passion of the ’80s,” he declared. The 1982 sitcom Family Ties gave the world Steven and Elyse Keaton, a pair of aging hippies who are raising an arch-conservative disciple of Ronald Reagan; it was thus the mirror image of 1970s comedies like All in the Family. Michael J. Fox’s perpetually tie-sporting Alex P. Keaton became a teenage heartthrob because, as Huey Lewis would soon be singing, it was now “Hip to be Square.” Yes, that was true even in the world of rock and roll, where bland-looking fellows like Huey Lewis and Phil Collins, who might very well have inhabited the cubicle next to yours at an accounting firm, were improbably selling millions of records and seeing their mugs all over MTV.

No institution benefited more from this rolling back of the countercultural tide than the American military. Just prior to Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the military’s morale as well as its public reputation were at their lowest ebb of the century. All four services were widely perceived as a refuge for psychopaths, deadbeats, and, increasingly, druggies. A leaked internal survey conducted by the Pentagon in 1980 found that about 27 percent of all military personnel were willing to admit to using illegal drugs at least once per month; the real numbers were almost certainly higher. Another survey found that one in twelve of American soldiers stationed in West Germany, the very front line of the Cold War, had a daily hashish habit. In the minds of many, only a comprehensively baked military could explain a colossal cock-up like the failed attempt to rescue American hostages in Iran in April of 1980, which managed to lose eight soldiers, six helicopters, and a C-130 transport plane without ever even making contact with the enemy. Small wonder that this bunch had been booted out of Vietnam with their tails between their legs by a bunch of shoeless rebels in black pajamas.

The military’s public rehabilitation began immediately upon Ronald Reagan’s election. Reagan not only continued but vastly expanded the military buildup his predecessor Jimmy Carter had begun, whilst declaring at every opportunity his pride and confidence in the nation’s fighting men and women. He was also willing to use the military in ways that hadn’t been dared since the withdrawal from Vietnam. As I recounted recently in another article, the Reagan administration began probing and feinting toward the Soviet Union, testing the boundaries of its airspace as well as its resolve in ways almost unprecedented since the Cold War had begun all those decades before. On October 25, 1983, the United States invaded the tiny Caribbean island nation of Grenada to depose a Soviet-friendly junta that had seized power just days earlier. In later years this attack by a nation of 235 million on a nation of less than 100,000, a nation which was hardly in a position to harm it even had it wanted to, would be roundly mocked. But at the time the quick-and-easy victory was taken as nothing less than a validation of the American military by large swathes of the American public, as a sign that the military could actually accomplish something, could win a war, definitively and (relatively) cleanly — no matter how modest the opponent.

We need only look to popular culture to see the public’s changing attitude toward the military writ large. Vietnam veterans, previously denounced as baby killers and conscienceless automatons, were by mid-decade shown all over television as good, dutiful men betrayed and scorned by their nation. For a while there it seemed like every popular action series on the air featured one or more psychically wounded but unbowed Vietnam vets as protagonists, still loyal to the country that had been so disloyal to them: The A-Team; Magnum, P.I.; Airwolf; Miami Vice. During the commercial breaks of these teenage-boy-friendly entertainments, the armed forces ran their slick new breed of recruiting commercials to attract a new generation of action heroes. The country had lost its way for a while, seduced by carping liberalism and undermined by the self-doubt it engendered, but now America — and with it the American military — were back, stronger, prouder, and better than ever. It was “morning again in America.”

Arguably the most important individual military popularizer of all inhabited, surprisingly, the more traditionally staid realm of books. Tom Clancy was a husband and father of two in his mid-thirties, an insurance agent living a comfortable middle-class existence in Baltimore, when he determined to combine his lifelong fascination with military tactics and weaponry with his lifelong desire to be a writer. Published in 1984 by, of all people, the Naval Institute Press — the first novel they had ever handled — his The Hunt for Red October tells the story of the eponymous Soviet missile submarine, whose captain has decided to defect along with his vessel to the West. A merry, extended chase ensues involving the navies of several nations — the Soviets trying to capture or sink the Red October, the West trying to aid its escape without provoking World War III. It’s a crackerjack thriller in its own right for the casual reader, but it was Clancy’s penchant for piling on layer after layer of technical detail and his unabashed celebration of military culture that earned him the love of those who were or had been military personnel, those who admired them, and many a teenage boy who dreamed of one day being among them. Clancy’s worldview was, shall we say, uncluttered by excessive nuance: “I think we’re the good guys and they’re the bad guys. Don’t you?” Many Americans in the 1980s, their numbers famously including President Reagan himself, did indeed agree, or at least found it comforting to enjoy a story built around that premise. I must confess that I myself am hardly immune even today to the charms of early Tom Clancy.

By 1986, the year that Clancy published his second novel Red Storm Rising, the military’s rehabilitation was complete and then some. The biggest movie of that year was Top Gun, a flashy, stylish action flick about F-14 fighter pilots that played to the new fast-cutting MTV aesthetic, its cast headlined by an impossibly good-looking young Tom Cruise and its soundtrack stuffed with hits. I turned fourteen that year. I can remember my friends, many of them toting Hunt for Red October or Red Storm Rising under their arms, dreaming of becoming fighter pilots and bedding women like Top Gun‘s Kelly McGillis. Indeed, “fighter pilot” rivaled the teenage perennial of “rock star” for the title of coolest career in the world. The American military in general was as cool as it’s ever been.

Joining the likes of Tom Clancy and Tom Cruise as ambassadors of this idealized vision of the military life were the inimitable John William “Wild Bill” Stealey and his company MicroProse. Stealey himself was, as one couldn’t spend more than ten seconds in his presence without learning, a former Air Force pilot. Born in 1947, he graduated from the Air Force Academy, then spent six years as an active-duty pilot, first teaching others to fly in T-37 trainers and then guiding gigantic C-5 Galaxy transport aircraft all over the world. After his discharge he took an MBA from the Wharton School, then set off to make his way in the world of business whilst continuing to fly A-37s, the light attack variant of the T-37, on weekends for the Pennsylvania Air National Guard. By 1982 he had become Director of Strategic Planning for General Instruments, a company in the Baltimore suburb of Hunt Valley specializing in, as their advertisements proclaimed, “point-of-sale, state-lottery, off-track, and on-track wagering systems utilizing the most advanced mini- and microcomputer hardware and software technologies.” Also working at General Instruments, but otherwise moving in very different circles from the garrulous Wild Bill, was a Canadian immigrant named Sid Meier, a quiet but intense systems engineer in his late twenties who was well known by the nerdier denizens of Hunt Valley as the founder of the so-called Sid Meier’s Users Group, a thinly disguised piracy ring peopled with enthusiasts of the Atari 800 and its sibling models. Sid liked to say that he wasn’t actually playing the games he collected for pleasure, but rather analyzing them as technology, so what he was doing was okay.

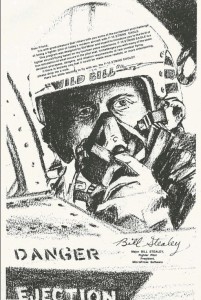

The first real conversation between Stealey and Meier has gone down in gaming legend. In May of 1982, the two found themselves thrown together in Las Vegas for a series of boring corporate meetings. They ended up at an arcade in the basement of the MGM Grand Hotel and Casino, in front of a game called Red Baron. Stealey sat down and scored 75,000 points, and was quite proud of himself. Then Meier racked up 150,000, and could have kept on going if he’d wanted to. When Stealey asked him how he, the quiet nerd, had beat a hotshot pilot, Meier said the opponents in the game had been programmed to follow just a handful of patterns, which he’d memorized whilst watching Stealey play. “It’s not very good,” he said. “I could write a better game in a week.” “If you could, I could sell it,” replied Stealey.

Sid Meier and Bill Stealey pose in 1988 with the actual Red Baron machine that had led to the formation of MicroProse six years earlier.

Much more than a week went by, and Stealey forgot about the exchange. But then, three months later, Meier padded up to him in the halls of General Instruments and handed him a disk containing a simple World War II shoot-em-up called Hellcat Ace. Shocked that he had come through, Stealey took it home, played it, and “wrote him a four-page memo about what was wrong with the flying and combat.” Seeing the disappointment on Meier’s face when he handed him the memo, Stealey thought that would be the end of it. But a week later Meier was back again, with another disk: “I fixed all of those things you mentioned.” His bluff well and truly called, Stealey had no choice but to get started trying to sell the thing.

First, of course, they would need a name for their company. Stealey initially looked for something with an Air Force association, but couldn’t come up with anything that rang right. For a while the two mulled over the awful name of “Smuggers Software,” incorporating an acronym for “Sid Meier’s Users Group.” But eventually Meier came up with “MicroProse.” After all, he noted, his code was basically prose for microcomputers. The “prose” also served as a pun on “pros” — professionals. With no better ideas on offer, Stealey reluctantly agreed: “It’ll be hard to remember, but once they got it, nobody will forget it.”

Packaging Meier’s game in a plastic baggie with a mimeographed cover sheet, Stealey started visiting all of the computer stores around Baltimore, giving them an early version of what would soon become known inside the industry as the Wild Bill Show — a combination of the traditional hard sell with buckets of Air Force bravado and a dollop of sheer charm to make the whole thing go down easy. Meier paid a local kid 25 cents per game to copy the disks and assemble the packages. By the end of 1982 sales had already reached almost 500 per month, at $15 wholesale per piece. Not bad for a side venture that Stealey had first justified to himself as a convenient way to get a tax write-off for his Volvo.

Early the following year Stealey managed by the time-honored technique of buying an advertisement to get Antic magazine to review Hellcat Ace. The review was favorable if not glowing: “While the graphics are not stunning, the game plays well and holds your interest with multiple skill levels and a variety of scenarios.” On the heels of this, MicroProse’s first real exposure outside the Baltimore area, Stealey took to calling computer stores all over the country, posing as a customer looking for Hellcat Ace. When they said they didn’t carry it, he would berate them in no uncertain terms and announce that he’d be taking his business to a competitor who did carry the game. After doing this a few times to a single store, he’d call again as himself: “Hello, this is John Stealey. I’m from MicroProse. I’d like to sell you Hellcat Ace.” The hapless proprietor on the other end of the line would breathe a sigh of relief, saying how “we’ve been getting all kinds of phone calls for that game.” And just like that, MicroProse would be in another shop.

While Stealey sold like a madman, Meier programmed like one, churning out new games at a staggering clip. With MicroProse not yet having self-identified as exclusively or even primarily a maker of simulations, Stealey just craved product from Meier — any sort of product. Meier delivered. He reworked the Hellcat Ace code to turn it into Spitfire Ace. He combined the arcade hit Donkey Kong with the Atari VCS hit Pitfall! to produce Floyd of the Jungle, whose most unique feature was the chance for up to four players to play simultaneously, thanks to the Atari 800’s four joystick ports. He made a top-down air-combat game called Wingman that also supported up to four players, playing in teams of leader and wingman. He made a game called Chopper Rescue that owed more than a little something to the recent Apple II smash Choplifter and supported up to eight players, taking turns. (It would later be reissued as Air Rescue I, its original name having been perhaps just a bit too close to Choplifter‘s for comfort.) He made a surprisingly intricate strategic war game called NATO Commander that anticipated the scenario of Red Storm Rising — a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, with the specter of nuclear weapons conveniently hand-waved away — three years before that book’s publication. And finally there was Solo Flight, a take on civilian aviation that was more simulation-oriented than its predecessors, including a VHF navigation system and an entertaining mail-delivery challenge in addition to its free-flight mode. All of these gushed out of him in barely eighteen months, during most of which he was still working at General Instruments during the day. They found their places on the product lists with which Stealey continued to bombard shops and, soon, the big distributors as MicroProse slowly won a seat with the big boys of the industry.

Stealey and Meier had an odd relationship. Far too different in background, personality, and priorities to ever be real friends, they were nevertheless the perfect business partners, each possessing in spades what the other conspicuously lacked. Meier brought to the table technical wizardry and, as would only more gradually become apparent, a genius for game design that at the very least puts him in the conversation today for the title of greatest designer in the history of the field. Stealey brought business savvy, drive, practicality, and a genius for promotion. Alone, Stealey would probably have had an impressive but boring career in big business of one stripe or another, while Meier would have spent his life working comfortable jobs whilst war-gaming and hacking code as a quiet hobby. They were two of the luckiest people in the world to have found each other; neither would have had a chance of making his mark on history without the other.

It might seem a dangerously imbalanced relationship, this pairing of an Air Force jock who hit a room like a force of nature with a quiet, bookish computer freak. At his worst, Stealey could indeed sound like a Svengali putting the screws to his lucrative pet savant. Look closer, however, and you had to realize that Stealey genuinely respected Meier, was in awe of his sheer intellectual firepower:

One Christmas, I gave him a book detailing the days of the Civil War. Five days later, he gave it back to me. I asked if he did not like the book. He said he loved it, but had already memorized all the key dates and events in it, and thought I might like to read it too. Sid is brilliant!

And Meier wasn’t quite the pushover he might first appear to be. Retiring and shy as he was by disposition, he was also every bit or more as strong-willed as Stealey, sometimes to an infuriating degree. As conservative and risk-averse in his personal life as he was bold and innovative in his programming and design, Meier refused to give up his day job at General Instruments for an astonishingly long time. After pitching in $1500 to help found MicroProse, he also refused to invest any more of his own capital in the company to set up offices and turn it into a real business. That sort of thing, he said, was Stealey’s responsibility. So Stealey took out a $15,000 personal loan instead, putting up his car as partial collateral. Most frustratingly of all, Meier clung stubbornly to his Atari 800 with that passion typical of a hacker’s first programming love, even as the cheaper Commodore 64 exploded in popularity.

It was the need to get MicroProse’s games onto the latter platform that prompted Stealey to bring on his first programmers not named Sid Meier, a couple of Meier’s buddies from his old Users Group. Grant Irani specialized in porting Meier’s games to the 64, while Andy Hollis used Meier’s codebase to make another Atari shoot-em-up, this time set in the Korean War, called MIG Alley Ace. Showing a bit more flexibility than Meier, he then ported his own game to the Commodore 64. He would go on to become almost as important to MicroProse as Meier himself.

Unlike so many of his peers, Stealey steered clear of the venture capitalists with their easy money as he built MicroProse. This led to some dicey moments as 1983 turned into 1984, and consumers started growing much more reluctant to shell out $25 or $30 for one of MicroProse’s simple games. The low point came in July of 1984, when, what with the distribution streams already glutted with products that weren’t selling anymore, MicroProse’s total orders amounted to exactly $27. About that time HESWare, never shy about taking the venture capitalists’ money and still flying high because of it, offered Stealey a cool $250,000 to buy Solo Flight outright and publish it as their own. When he asked Meier his opinion, Meier, as usual, initially declined to get involved with business decisions. But then, as Stealey walked away, Meier deigned to offer some quiet words of wisdom: “You know what? I heard you shouldn’t sell the family jewels.” Stealey turned HESWare down. HESWare imploded before the year was out; MicroProse would continue to sell Solo Flight, never a real hit but a modest, steady moneyspinner, for years to come.

Still, it was obvious that MicroProse needed to up their game if they wished to continue to exist past the looming industry shakeout. While with NATO Commander and Solo Flight he had already begun to move away from the simple action games that had gotten MicroProse off the ground, it was Sid Meier’s next game, F-15 Strike Eagle, that would set the template for the company for years to come. Stealey had been begging Meier for an F-15 game for some time, but Meier had been uncertain how to approach it. Now, with Solo Flight under his belt, he felt he was ready. F-15 Strike Eagle was a quantum leap in sophistication compared to what had come before it, moving MicroProse definitively out of the realm of shoot-em-ups and into that of real military simulations. The flight model was dramatically more realistic; indeed, the F-15 Strike Eagle aeronautics “engine” would become the basis for years of MicroProse simulations to come. The airplane’s array of weapons and defensive countermeasures were simulated with a reasonable degree of fidelity to their real-life counterparts. And the player could choose to fly any of seven missions drawn from the F-15’s service history, a couple of them ripped from recent headlines to portray events that happened in the Middle East a bare few months before the game’s release. F-15 Strike Eagle turned into a hit on a scale that dwarfed anything MicroProse had done before, a consistent bestseller for years, the game that made the company, both financially and reputationally. It became one of the most successful and long-lived computer games of the 1980s, with worldwide sales touching 1 million by 1990 — a stunning number for its era.

The games that followed steadily grew yet more sophisticated. Andy Hollis made an air-traffic-control simulation called Kennedy Approach that was crazily addictive. A new designer, William F. Denman, Jr., created an aerobatics simulation called Acrojet. Meanwhile the prolific Sid Meier wrote Silent Service, a World War II submarine simulation, and also three more strategic war games, MicroProse’s so-called “Command Series,” in partnership with one Ed Bever, holder of a doctorate in history: Crusade in Europe, Decision in the Desert, and Conflict in Vietnam. Unsurprisingly, neither the strategy games nor the civilian simulations sold on anywhere near the scale of F-15 Strike Eagle. Only Silent Service rivaled and, in its first few months of release, actually outdid F-15, rocketing past 250,000 in sales within eighteen months. Meier, who “didn’t value money too highly” in the words of Stealey, who never saw much of a reason to change his lifestyle despite his increasing income, who often left his paychecks lying on top of his refrigerator forgotten until accounting called to ask why their checks weren’t getting cashed, couldn’t have cared less about the relative sales numbers of his games or anyone else’s. Stealey, though, wasn’t so sanguine, and pushed more and more to make MicroProse exclusively a purveyor of military simulations.

It’s hard to blame him. F-15 Strike Eagle, Silent Service, and the MicroProse military simulations that would follow were the perfect games for their historical moment, the perfect games for Tom Clancy readers; Clancy was, not coincidentally, also blowing up big at exactly the same time. Like Clancy, MicroProse was, perverse as it may sound, all about making war fun again.

Indeed, fun was a critical component of MicroProse’s games, one overlooked by far too many of their competitors. MicroProse’s most obvious rival as a maker of simulations was SubLogic, maker of the perennial civilian Flight Simulator and a military version called simply Jet that put players in the cockpit of an F-16 or F-18. SubLogic, however, emphasized realism above all else, even when the calculations required to achieve it meant that their games chugged along at all of one or two frames per second on the hapless likes of a Commodore 64, the industry’s bread-and-butter platform. MicroProse, on the other hand, recognized that they were never really going to be able to realistically simulate an F-15 or a World War II submarine on a computer with 64 K. They settled for a much different balance of playability and fun, one that gave the player a feeling of really “being there” but that was accessible to beginners and, just as importantly, ran at a decent clip and looked reasonably attractive while doing so. Stealey himself admitted that “I can’t even land Flight Simulator, and I’ve got 3000 flying hours behind me!” Fred Schmidt, MicroProse’s first marketing director, delivers another telling quote:

We’re not trying to train fighter pilots or submarine captains. What we’re trying to do is give people who will never have a chance to go inside a submarine the opportunity to get inside one and take it for a spin around the block to see what it is like. Our simulations give them that chance. They get a close-up look at simulated real life. They feel it, they experience the adventure. And at the end of the adventure, we want them to feel they got their money’s worth.

There’s an obvious kinship here with the idea of “aesthetic simulations” as described by Michael Bate, designer of Accolade hits like Ace of Aces. MicroProse, though, pushed the realism meter much further than Bate, to just before the point where the games would lose so much accessibility as to become niche products. Stealey was never interested in being niche. The peculiar genius of MicroProse, and particularly of Sid Meier, who contributed extensively even to most MicroProse games that didn’t credit him as lead designer, was to know just where that point was. This was yet another quality they shared with Tom Clancy.

That said, make no mistake: the veneer of realism, however superficial it might sometimes be, was every bit as important to MicroProse’s appeal as it was to Clancy’s. And the veneer of authenticity provided by Wild Bill Stealey, however superficial it might be — sorry, Wild Bill — was critical to achieving this impression. Stealey had started playing in earnest the role of the hotshot fighter jock by the time of F-15 Strike Eagle, the manual for which opened with an illustration of him in his flight suit and a dedication saying the game would “introduce you to the thrill of fighter-aircraft flying based on my fourteen years experience.” Under his signature is written “Fighter Pilot,” before the more apropos title of “President, MicroProse Software.” All of which probably read more impressively to those not aware that Stealey had never actually flown an F-15 or any other supersonic fighter, having spent his career flying subsonic trainers, transport aircraft, and second-string light attack planes. All, I have no doubt, are critical roles requiring a great deal of skill and bravery — but, nevertheless, the appellation of “fighter pilot” is at best a stretch.

Stealey today freely admits that he was playing a character — not to say a caricature — for much of his time at MicroProse, that going to conventions and interviews wearing his flight suit, for God’s sake, wasn’t exactly an uncalculated decision. He also admits that other industry bigwigs, among them Trip Hawkins, loved to make fun of him for it. But, he says, “how do you remember a small company? It needs something special. All we had was Sid and Wild Bill.” And Sid certainly wasn’t interested in helping to sell his games.

Stealey seemed to particularly delight in doing his swaggering Right Stuff schtick for the press in Europe, where MicroProse had set up a subsidiary to sell their games already by 1986. Wild Bill in full flight was an experience that deserves a little gallery of its own. So, here are the reports of just a few mild-mannered journalists lucky or unlucky enough to be assigned to interview Stealey.

“See that,” he bawled, tapping the largest ring I’ve ever seen on my desk, waking up the technical experts in the Commodore User offices, “that’s a genuine American Air Force Fighter Pilot’s Ring. Do that in a barroom in the States and you get instant service… they know you’re a fighter pilot.”

As far as Stealey is concerned, the only real pilots are fighter pilots. “What about airline pilots?” I ask. “Bus drivers,” says Wild Bill. Alright then — what about the pilots who talk endlessly about the freedom, the solitude, and the spiritual experience of flying?

“You wanna talk spiritual? I’ll tell you what’s spiritual… flying upside down in an F-15, doing mach 1.5 high above the Rocky Mountains, with the sun behind and the Pacific Ocean ahead of you… that’s spiritual… the rest is just sightseeing.

“Whooosh,” says Wild Bill, thrusting his hand through the air to illustrate his point.

“I’m selling these games to men. If you haven’t got the right stuff, I don’t want to know. I’m not interested in the kind of guy who just wants a short thrill. If you want to spend £6 on an arcade game that you’re going to play for half an hour, I don’t want you buying my software.”

Despite MicroProse’s size, growth has been accomplished at an intentionally conservative rate. Bill Stealey attributes this to his fighter-pilot background. Wait a minute — fighter pilots as conservative? “Of course fighter pilots are conservative. We wait until we accumulate sufficient data and then we wax the bad guys.”

Bill Stealey tells you all this in his usual verbal assault mode. Being on the other end of this barrage is to feel disoriented and dazed. Gradually, your senses return. You realize that there are other software houses out there, a possibility Bill hardly admits.

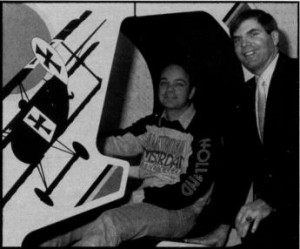

As soon as finances allowed, MicroProse took the Wild Bill Show to the next level by purchasing for him an unusual sort of company plane: a Navy surplus T-28 Trojan trainer. The plane cost a small fortune to keep in service, but it was worth it to let Stealey take up queasy, knock-kneed gaming journalists — and, occasionally, the lucky MicroProse fan — and toss the T-28 through some high-performance aerobatics.

Wild Bill prepares to terrorize another journalist, in this case Jim Gracely, Managing Editor of Commodore Magazine.

Of course, one person’s charming fighter jock is another’s ugly American. Not all journalists, especially in Europe, were entirely taken with either Stealey’s persona or with what one Commodore User journalist pointedly described as the “militaristic and Cold War tinge of MicroProse’s products.” This undercurrent of grumbling would erupt into a real controversy in Europe upon the release of Gunship, MicroProse’s big game of 1986.

By far MicroProse’s most ambitious, expensive, extended, and problem-plagued project yet, Gunship was helmed by a new arrival, a veteran designer of board games named Arnold Hendrick. Another helicopter game, it was originally conceived as a science-fictional “cops and robbers” scenario, playing on the odd but significant fascination the American media of the mid-1980s suddenly had with futuristic helicopters — think Blue Thunder and Airwolf. Work on the game began in earnest in April of 1985, with an announced shipping date of November of the same year, but Hendrick’s little team struggled mightily to devise a suitable flight model and graphics engine. At last, with two months to go, Meier wrote a new 3D aviation engine from scratch in just one month on a prototype of Commodore’s new 68000-based computer, the Amiga. It was decided to delay the game “indefinitely,” to make a “massive redeployment” in Stealey’s typical military jargon and port Meier’s work back to the little Commodore 64, the platform MicroProse knew best and the one that consistently sold best. With Stealey increasingly eager to define MicroProse exclusively as a maker of realistic simulations, the premise of the game was overhauled as well, to become a more sober — relatively speaking — depiction of the real-world AH-64 Apache assault chopper. By the time it finally arrived on the market in late 1986, it had absorbed three times as much time as expected and its development team had grown to four times the size anticipated. MicroProse had come a long way from the days of Floyd of the Jungle.

Just about everyone inside the games industry agreed that the delay had been worth it; this was MicroProse’s best game yet. Gunship‘s most innovative feature, destined to have a major impact not only on future games from MicroProse but on future games in general, was the way it let you simulate not just an individual mission but an entire career. When you start the game, you create and name a pilot of your own, a greenhorn of a sergeant. You then take on missions of your choice in any of four regions, picking and choosing as you will among four wars that are apparently all going on at the same time: Southeast Asia, Central America, the Middle East, or Western Europe (i.e., the Big One, a full-on Soviet invasion). If you perform well, you earn medals and promotions. If you get shot down you may or may not survive, and depending on where you crash-land may end up a prisoner of war. Either death or capture marks the definitive end to your Gunship career; this invests every moment spent in the combat zones with extra tension. The persistent career gives Gunship an element lacking from MicroProse’s previous simulations: a larger objective, larger stakes, beyond the successful completion of any given mission. It invests the game with an overarching if entirely generative plot arc of sorts as well as the addictive character-building progression of a CRPG, adding so much to the experience that career modes would quickly become a staple of simulations to come.

But some bureaucrats in West Germany were not so taken with Gunship as most gamers. There the “Bundesprüfstelle für Jugendgefährdende Schriften,” a list of writings and other communications that should not be sold to minors or even displayed in shops which they could enter, unexpectedly added Gunship to their rolls, to be followed shortly thereafter by F-15 Strike Eagle and Silent Service for good measure, for the sin of “promoting militarism” and thus being “morally corruptive and coarsening for the young user.” West Germany at the time constituted only about 1 percent of MicroProse’s business, but was likely the most rapidly expanding market for computers and computer games in the world. The blacklisting meant that these three games, which together constituted the vast majority of MicroProse’s sales in West Germany or anywhere else, could be sold only in shops offering a separate, adults-only section with its own entrance. Nor could they be advertised in magazines, or anywhere else where the teenage boys who bought MicroProse’s games in such numbers were able to see them. The games were, in other words, given the legal status of pornography: not, strictly speaking, censored, but made very difficult for people, especially young people, to acquire or even to find out about. If anything, it would now be harder for even an adult to get his hands on a MicroProse game than a porn film. There was after all a shopping infrastructure set up to support porn aficionados. There were no equivalent shops for games; certainly no computer store was likely to make a new entrance just to sell a few games. Thus the decision effectively killed MicroProse in West Germany. Stealey embarked on a long, exhausting battle with the German courts to have the decisions overturned. By the time he was able to get the Silent Service ban lifted, in 1988, that game was getting old enough that the issue was becoming irrelevant. Gunship and F-15 Strike Eagle took even longer to get stricken from the blacklist.

The debate over free speech and its limits is of course a complicated one, and one on which Germany, thanks to its horrific legacy of Nazism and its determination to ensure that nothing like that ever happens again, tends to have a somewhat different perspective than the United States. The authorities’ concerns about “militarism” also reflected a marked difference in attitude on the part of continental Western Europe from that of the anglosphere of the United States and Britain, both beneficiaries (or victims, if you prefer) of recent conservative revolutions led by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher respectively. Europeans found it more difficult to be so blasé about the prospect of war with the Soviet Union — a war which would almost certainly be fought on their soil, with all the civilian death, destruction, and suffering that implied. In West Germany, blithely choosing to send your fictional Gunship pilot to the Western Europe region to fight against what the manual gushingly described as the “first team” in the “big time” struck much closer to home.

MicroProse was also involved in another, more cut-and-dried sort of controversy at the time of Gunship. Long before MicroProse, there had already existed a company called “MicroPro,” maker of the very popular WordStar word processor. As soon as MicroProse grew big enough to be noticed, MicroPro had begun to call and send letters of protest. At last, in 1986, they sued for trademark infringement. MicroProse, who really didn’t have a legal leg to stand on, could only negotiate for time; the settlement stipulated that they had to choose a new name by 1988. But in the end the whole thing came to nothing when MicroPro abruptly changed their own name instead, to WordStar International, and let MicroProse off the hook.

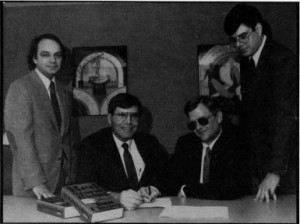

In the big picture these were all minor hiccups. MicroProse would continue to make their accessible, entertaining, and usually bestselling military simulations for years to come after Gunship: Airborne Ranger, F-19 Stealth Fighter, F-15 Strike Eagle II, M1 Tank Platoon, just to begin the list. In 1988 they cemented once and for all their status as the game publisher for the Tom Clancy generation with the release of Red Storm Rising, the game of the book.

The ultimate meeting of the simulation-industrial complex: Sid Meier, Wild Bill Stealey, Tom Clancy, and Larry Bond (Clancy’s consultant and collaborator on the Red Storm Rising scenario, as well as author of the Harpoon naval board game).

By then, however, the restlessly creative Sid Meier was also finding ways to push beyond the military-simulation template to which Stealey would have happily held him in perpetuity. In doing so he would create some of the best, most important games in history. Sid Meier and MicroProse are thus destined to be featured players around here for quite some time to come.

(Lots and lots of sources this time around. Useful for the article as a whole: the books Gamers at Work by Morgan Ramsay, Computer Gaming World of November 1987, Commodore Magazine of September 1987. Tom Clancy and cultural background: the book Command and Control by Eric Schlosser, New York Times Magazine of May 1 1988, Computer Gaming World of July 1988. General Instruments and the Red Baron anecdote: ComputerWorld of May 16 1977, Computer Gaming World of June 1988. On MicroProse’s name and the dispute with MicroPro: Computer Gaming World of October 1987 and November 1991, A.N.A.L.O.G. of September 1987. Reviews, advertisements, and anecdotes about individual games: Antic of May 1983 and June 1984 and November 1984, Computer Gaming World of January/February 1986 and March 1987, Commodore Magazine of December 1988, C.U. Amiga of August 1990. On the “promoting militarism” controversy: Computer Gaming Forum of Fall 1987 and Winter 1987, Commodore User of June 1987, Computer Gaming World of May 1988, Aktueller Software Markt of May 1989. Examples of the Wild Bill Show: Commodore User of May 1985, Your Computer of May 1985 and November 1987, Commodore Disk User of November 1987, Popular Computing Weekly of May 1 1986, Games Machine of October 1988 and November 1988. On the development of Gunship: the book Gunship Academy by Richard Sheffield. This article’s “cover art” was taken from the MicroProse feature in the September 1987 Commodore Magazine. If you’d like to see a premiere MicroProse simulation from this era in action, feel free to download the Commodore 64 version of Gunship from right here.)