Earth Orbit, on a satellite

The satellite you're riding is about twenty feet long, and shaped like a beer can.

>z

Time passes.

A red flash draws your eyes to the ground below, where the contrail of a missile is climbing into the stratosphere.

>z

Time passes.

The maneuvering thrusters on the satellite fire, turning the nose until it faces the ascending missile.

>z

Time passes.

The satellite erupts in a savage glare that lights up the ground below. A beam of violet radiation flashes downward, obliterating the distant missile. Unfortunately, you have little time to admire this triumph of engineering before the satellite's blast incinerates you.

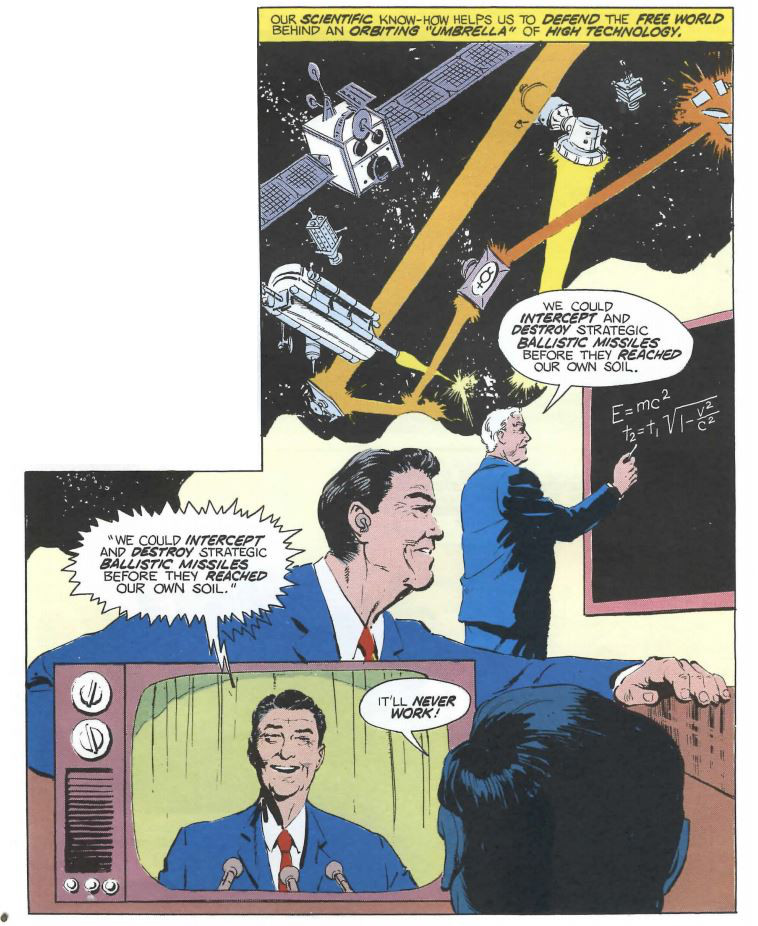

Trinity aims in 256 K of text adventure to chronicle at least fifty years of humanity’s relationship to the atomic bomb, as encapsulated into seven vignettes. Two of these, the one dealing with the long-dreaded full-on nuclear war that begins with you on vacation in London’s Kensington Gardens and the one you see above involving a functioning version of Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative (a proposition that all by itself justifies Trinity‘s “Fantasy” genre tag, as we’ll soon see), are actually speculative rather than historical, taking place at some point in the near future. The satirical comic that accompanies the game also reserves space for Reagan and his dream. It’s a bold choice to put Reagan himself in there, undisguised by pseudonymous machinations like A Mind Forever Voyaging‘s “Richard Ryder” — even a brave one for a company that was hardly in a position to alienate potential players. Trinity, you see, was released at the absolute zenith of Reagan’s popularity. While the comic and the game it accompanies hardly add up to a scathing sustained indictment a la A Mind Forever Voyaging, they do cast him as yet one more Cold Warrior in a conservative blue suit leading the world further along the garden path to the unthinkable. Today I’d like to look at this “orbiting ‘umbrella’ of high technology” that Trinity postulates — correctly — isn’t really going to help us all that much at all when the missiles start to fly. Along the way we’ll get a chance to explore some of the underpinnings of the nuclear standoff and also the way it came to an anticlimactically sudden end, so thankfully at odds with Trinity‘s more dramatic predictions of the supposed inevitable.

In November of 1985, while Trinity was in development, Ronald Reagan and the new Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev met for the first American/Soviet summit of Reagan’s Presidency. The fact that the summit took place at all was almost entirely down to the efforts of Gorbachev, who quite skillfully made it politically impossible for Reagan not to attend. It marked the first time Reagan had actually talked with his Soviet counterpart face to face in his almost five years as President. The two men, as contemporary press reports would have it, “took the measure of each other” and largely liked what they saw, but came to no agreements. The second summit, held in Reykjavik, Iceland, in October of the following year, came to within a hair’s breadth of a major deal that would have started the superpowers down the road to the complete elimination of nuclear armaments and effectively marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War. The only stumbling block was the Strategic Defense Initiative. Gorbachev was adamant that Reagan give it up, or at least limit it to “laboratory testing”; Reagan just as adamantly refused. He repeatedly expressed to both Gorbachev and the press his bafflement at this alleged intransigence. SDI, he said, was to be a technology of defense, a technology for peace. His favorite metaphor was SDI as a nuclear “gas mask.” The major powers of the world had all banned poison gas by treaty after World War I, and, rather extraordinarily, even kept to that bargain through all the other horrors of World War II. Still, no one had thrown away their gas-mask stockpiles, and the knowledge that other countries still possessed them had just possibly helped to keep everyone honest. SDI, Reagan said, could serve the same purpose in the realm of nuclear weapons. He even made an extraordinary offer: the United States would be willing to give SDI to the Soviets “at cost” — whatever that meant — as soon as it was ready, as long as the Soviets would also be willing to share any fruits of their own (largely nonexistent) research. That way everyone could have nuclear gas masks! How could anyone who genuinely hoped and planned not to use nuclear weapons anyway possibly object to terms like that?

Gorbachev had a different view of the matter. He saw SDI as an inherently destabilizing force that would effectively jettison not one but two of the tacit agreements of the Cold War that had so far prevented a nuclear apocalypse. Would any responsible leader easily accept such an engine of chaos in return for a vague promise to “share” the technology? Would Reagan? It’s very difficult to know what was behind Reagan’s seeming naivete. Certainly his advisers knew that his folksy analogies hardly began to address Gorbachev’s very real and very reasonable concerns. If the shoe had been on the other foot, they would have had the same reaction. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger had demonstrated that in December of 1983, when he had said, “I can’t imagine a more destabilizing factor for the world than if the Soviets should acquire a thoroughly reliable defense against these missiles before we did.” As for Reagan himself, who knows? Your opinion on the matter depends on how you take this famous but enigmatic man whom conservatives have always found as easy to deify as liberals to demonize. Was he a bold visionary who saved his country from itself, or a Machiavellian schemer who used a genial persona to institute an uglier, more heartless version of America? Or was he just a clueless if good-natured and very, very lucky bumbler? Or was he still the experienced actor, out there hitting his marks and selling the policies of his handlers like he had once shilled for General Electric? Regardless, let’s try to do more justice to Gorbachev’s concerns about SDI than Reagan did at their summits.

It’s kind of amazing that the Cold War never led to weapons in space. It certainly didn’t have to be that way. Histories today note what a shock it was to American pride and confidence when the Soviet Union became the first nation to successfully launch a satellite on October 4, 1957. That’s true enough, but a glance at the newspapers from the time also reveals less abstract fears. Now that the Soviets had satellites, people expected them to weaponize them, to use them to start dropping atomic bombs on their heads from space. One rumor, which amazingly turned out to have a basis in fact, claimed the Soviets planned to nuke the Moon, leading to speculation on what would happen if their missile was to miss the surface, boomerang around the Moon, and come back to Earth — talk about being hoisted by one’s own petard! The United States’s response to the Soviets’ satellite was par for the course during the Cold War: panicked, often ill-considered activity in the name of not falling behind. Initial responsibility for space was given to the military. The Navy and the Air Force, who often seemed to distrust one another more than either did the Soviets, promptly started squabbling over who owned this new seascape or skyscape, which depending on how you looked at it and how you picked your metaphors could reasonably be assumed to belong to either. While the Naval Research Laboratory struggled to get the United States’s first satellite into space, the more ambitious dreamers at the Air Force Special Weapons Center made their own secret plans to nuke the Moon as a show of force and mulled the construction of a manned secret spy base there.

But then, on July 29, 1958, President Eisenhower signed the bill that would transform the tiny National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics into the soon-to-be massive National Aeronautics and Space Administration — NASA. While NASA’s charter duly charged the new agency with making any “discoveries” available for “national defense” and with “the preservation of the role of the United States as a leader in aeronautical and space science and technology,” those goals came only after more high-toned abstractions like “the expansion of human knowledge” and the use of space for “peaceful and scientific purposes.” NASA was something of an early propaganda coup at a time when very little seemed to be going right with astronautics in the United States. The Soviet leadership had little choice but to accept the idea, publicly at least, of space exploration as a fundamentally peaceful endeavor. In 1967 the United States and the Soviet Union became signatories along with many other nations to the Outer Space Treaty that enshrined the peaceful status quo into international law. By way of compensation, the first operational ICBMs had started to come online by the end of the 1950s, giving both superpowers a way of dealing impersonal death from the stratosphere without having to rely on wonky satellites.

This is not to say that the Cold War never made it into space in any form. Far from it. Apollo, that grandest adventure of the twentieth century, would never have happened without the impetus of geopolitics. The Apollo 11 astronauts may have left a message on the Moon saying they had “come in peace for all mankind,” may have even believed it at some level, but that was hardly the whole story. President Kennedy, the architect of it all, had no illusions about the real purpose of his Moon pronouncement. “Everything that we do ought to be really tied into getting onto the Moon ahead of the Russians,” he told NASA Administrator James Webb in 1962. “Otherwise we shouldn’t be spending this kind of money because I’m not that interested in space.” The Moon Race, like war, was diplomacy through other means. As such, the division between military and civilian was not always all that clear. For instance, the first Americans to fly into orbit, like the first Soviets, did so mounted atop repurposed ICBMs.

Indeed, neither the American nor the Soviet military had any interest in leaving space entirely to the civilians. If one of the goals of NASA’s formation had been to eliminate duplications of effort, it didn’t entirely succeed. The Air Force in particular proved very reluctant to give up on their own manned space efforts, developing during the 1960s the X-15 rocket plane that Neil Armstrong among others flew to the edge of orbit, the cancelled Dyna-Soar space plane, and even a manned space station that also never got off the drawing board. Planners in both the United States and the Soviet Union seemed to treat the 1967 Outer Space Treaty as almost a temporary accord, waiting for the other shoe to drop and for the militarization of space to begin in earnest. I’ve already described in an earlier article how, once the Moon Race was over, NASA was forced to make an unholy alliance with the Air Force to build the space shuttle, whose very flight profile was designed to allow it to avoid space-based weaponry that didn’t yet actually exist.

Yet the most immediate and far-reaching military application of space proved to be reconnaissance satellites. Well before the 1960s were out these orbiting spies had become vital parts of the intelligence apparatus of both the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as vital tools for the detection of ICBM launches by the other side — yet another component of the ever-evolving balance of terror. Still, restrained by treaty, habit, and concern over what it might make the other guys do, neither of the superpowers ever progressed to the logical step of trying to shoot down those satellites that were spying on their countries. If you had told people in 1957 that there would still be effectively no weapons in space almost thirty years later, that there would never have been anything even remotely resembling a battle in space, I think they would be quite surprised.

But now SDI had come along and, at least in the Soviets’ view, threatened to undermine that tradition. They need only take at face value early reports of SDI’s potential implementations, which were all over the American popular media by the time of Reagan’s 1984 reelection campaign, to have ample grounds for concern. One early plan, proposed in apparent earnest by a committee who may have seen The Battle of Britain (or Star Wars) a few too many times, would have the United States and its allies protected by squadrons of orbiting manned fighter planes, who would rocket to the rescue to shoot down encroaching ICBMs, their daring pilots presumably wearing dashing scarves and using phrases like “Tally ho!” A more grounded plan, relatively speaking, was the one for hundreds of “orbiting battle stations” equipped with particle-beam weapons or missiles of their own — hey, whatever works — to pick off the ICBMs. Of course, as soon as these gadgets came into being the Soviets would have to develop gadgets of their own to try to take them out. Thus a precious accord would be shattered forever. To the Soviets, SDI felt like a betrayal, a breaking of a sacred trust that had so far kept people and satellites in space from having to shoot at each other and in doing so had just possibly prevented the development of a new generation of horrific weaponry.

And yet this was if anything the more modest of the two outrages they saw being inflicted on the world by SDI. The biggest problem was that it could be both a symptom and a cause of the ending of the old MAD doctrine — Mutually Assured Destruction — that had been the guiding principle of both superpowers for over twenty years and that had prevented them from blowing one another up along with the rest of the world. On its surface, the MAD formulation is simplicity itself. I have enough nuclear weapons to destroy your country — or at least to do unacceptable damage to it — and a window of time to launch them at you between the time I realize that you’ve launched yours at me and the time that yours actually hit me. Further, neither of us has the ability to stop the missiles of the other — at least, not enough of them. Therefore we’d best find some way to get along and not shoot missiles at each other. One comparison, so favored by Reagan that he drove Gorbachev crazy by using it over and over again at each of their summits, is that of two movie mobsters with cocked and loaded pistols pointed at each others’ heads.

That well-intentioned comparison is also a rather facile one. The difference is a matter of degree. Many of us had MAD, that most fundamental doctrine of the Cold War, engrained in us as schoolchildren to such a degree that it might be hard for us to really think about its horribleness anymore. Nevertheless, I’d like for us to try to do so now. Let’s think in particular about its basic psychological prerequisites. In order for the threat of nuclear annihilation to be an effective deterrent, in order for it never to be carried out, it must paradoxically be a real threat, one which absolutely, unquestionably would be carried out if the order was given. If the other side was ever to suspect that we were not willing to destroy them, the deterrent would evaporate. So, we must create an entire military superstructure, a veritable subculture, of many thousands of people all willing to unquestioningly annihilate tens or hundreds of millions of people. Indeed, said annihilation is the entire purpose of their professional existence. They sit in their missile silos or in their ready rooms or cruise the world in their submarines waiting for the order to push that button or turn that key that will quite literally end existence as they know it, insulated from the incalculable suffering that action will cause inside the very same sorts of “clean, carpeted, warmed, and well-lighted offices” that Reagan once described as the domain of the Soviet Union’s totalitarian leadership alone. If the rise of this sort of antiseptic killing is the tragedy of the twentieth century, the doctrine of MAD represents it taken to its well-nigh incomprehensible extreme.

MAD, requiring as it did people to be always ready and able to carry out genocide so that they would not have to carry out genocide, struck a perilous psychological balance. Things had the potential to go sideways when one of these actors in what most people hoped would be Waiting for Godot started to get a little bit too ready and able — in short, when someone started to believe that he could win. See for example General Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command from its inception until 1965 and the inspiration for Dr. Strangelove‘s unhinged General Jack Ripper. LeMay believed to his dying day that the United States had “lost” the Cuban Missile Crisis because President Kennedy had squandered his chance to finally just attack the Soviet Union and be done with it; talked of the killing of 100 million human beings as a worthwhile trade-off for the decapitation of the Soviet leadership; openly campaigned for and sought ways to covertly acquire the metaphorical keys to the nuclear arsenal, to be used solely at his own dubious discretion. “If I see that the Russians are amassing their planes for an attack, I’m going to knock the shit out of them before they take off the ground,” he once told a civil-defense committee. When told that such an action would represent insubordination to the point of treason, he replied, “I don’t care. It’s my policy. That’s what I’m going to do.” Tellingly, Dr. Strangelove itself was originally envisioned as a realistic thriller. The film descended into black comedy only when Stanley Kubrick started his research and discovered that so much of the reality was, well, blackly comic. Much in Dr. Strangelove that moviegoers of 1964 took as satire was in fact plain truth.

If the belief by a single individual that a nuclear war can be won is dangerous, an institutionalized version of that belief might just be the most dangerous thing in the world. And here we get to the heart of the Soviets’ almost visceral aversion to SDI, for it seemed to them and many others a product of just such a belief.

During the mid-1970s, when détente was still the watchword of the day, a group of Washington old-timers and newly arrived whiz kids formed something with the Orwellian name of The Committee on the Present Danger. Its leading light was one Paul Nitze. A name few Americans then or now are likely to recognize, Nitze had been a Washington insider since the 1940s and would remain a leading voice in Cold War policy for literally the entire duration of the Cold War. He and his colleagues, many of them part of a new generation of so-called “neoconservative” ideologues, claimed that détente was a sham, that “the Soviets do not agree with the Americans that nuclear war is unthinkable and unwinnable and that the only objective of strategic doctrine must be mutual deterrence.” On the contrary, they were preparing for “war-fighting, war-surviving, and war-winning.” Their means for accomplishing the latter two objectives would be an elaborate civil-defense program that was supposedly so effective as to reduce their casualties in an all-out nuclear exchange to about 10 percent of what the United States could expect. The Committee offered little or no proof for these assertions and many others like them. Many simply assumed that the well-connected Nitze must have access to secret intelligence sources which he couldn’t name. If so, they were secret indeed. When the CIA, alarmed by claims of Soviet preparedness in the Committee’s reports that were completely new to them, instituted a two-year investigation to get to the bottom of it all, they couldn’t find any evidence whatsoever of any unusual civil-defense programs, much less any secret plans to start and win a nuclear war. It appears that Nitze and his colleagues exaggerated wildly and, when even that wouldn’t serve their ends, just made stuff up. (This pattern of “fixing the intelligence” would remain with Committee veterans for decades, leading most notably to the Iraq invasion of 2003.)

Throughout the Carter administration the Committee lobbied anyone who would listen, using the same sort of paranoid circular logic that had led to the nuclear-arms race in the first place. The Soviets, they said, have secretly abandoned the MAD strategy and embarked on a nuclear-war-winning strategy in its place. Therefore we must do likewise. There could be no American counterpart to the magical Soviet civil-defense measures that could somehow protect 90 percent of their population from the blasts of nuclear weapons and the long years of radioactive fall-out that would follow. This was because civil defense was “unattractive” to an “open society” (“unattractiveness” being a strangely weak justification for not doing something in the face of what the Committee claimed was an immediate existential threat, but so be it). One thing the United States could and must do in response was to engage in a huge nuclear- and conventional-arms buildup. That way it could be sure to hammer the Soviets inside their impregnable tunnels — or wherever it was they would all be going — just as hard as possible. But in addition, the United States must come up with a defense of its own.

Although Carter engaged in a major military buildup in his own right, his was nowhere near big enough in the Committee’s eyes. But then came the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan. Reagan took all of the Committee’s positions to heart and, indeed, took most of its most prominent members into his administration. Their new approach to geopolitical strategy was immediately apparent, and immediately destabilizing. Their endless military feints and probes and aggressive rhetoric seemed almost to have the intention of starting a war with the Soviet Union, a war they seemed to welcome whilst being bizarrely dismissive of its potentially world-ending consequences. Their comments read like extracts from Trinity‘s satirically gung-ho accompanying comic. “Nuclear war is a destructive thing, but it is still in large part a physics problem,” said one official. “If there are enough shovels to go around, everybody’s going to make it. It’s the dirt that does it,” said another. Asked if he thought that a nuclear war was “winnable,” Caspar Weinberger replied, “We certainly are not planning to be defeated.” And then, in March of that fraught year of 1983 when the administration almost got the nuclear war it seemed to be courting, came Reagan’s SDI speech.

The most important thing to understand about SDI is that it was always a fantasy, a chimera chased by politicians and strategists who dearly wished it was possible. The only actual scientist amongst those who lobbied for it was Edward Teller, well known to the public as the father of the hydrogen bomb. One of the few participants in the Manhattan Project which had built the first atomic bomb more than 35 years before still active in public life at the time that Reagan took office, Teller was a brilliant scientist when he wanted to be, but one whose findings and predictions were often tainted by his strident anti-communism and a passion for nuclear weapons that could leave him sounding as unhinged as General LeMay. Teller seldom saw a problem that couldn’t be solved just by throwing a hydrogen bomb or two at it. His response to Carter’s decision to return the Panama Canal to Panama, for instance, was to recommend quickly digging a new one across some more cooperative Central American country using hydrogen bombs. Now, alone amongst his scientific peers, Teller told the Reagan administration that SDI was possible. He claimed that he could create X-ray beams in space by, naturally, detonating hydrogen bombs just so. These could be aimed at enemy missiles, zapping them out of the sky. The whole system could be researched, built, and put into service within five years. As evidence, he offered some inconclusive preliminary results derived from experimental underground explosions. It was all completely ridiculous; we still don’t know how to create such X-ray beams today, decades on. But it was also exactly the sort of superficially credible scientific endorsement — and from the father of the hydrogen bomb, no less! — that the Reagan administration needed.

Reagan coasted to reelection in 1984 in a campaign that felt more like a victory lap, buoyed by “Morning Again in America,” an energetic economy, and a military buildup that had SDI as one of its key components. The administration lobbied Congress to give the SDI project twice the inflation-adjusted funding as that received by the Manhattan Project at the height of World War II. With no obviously promising paths at all to follow, SDI opted for the spaghetti approach, throwing lots and lots of stuff at the wall in the hope that something would stick. Thus it devolved into a whole lot of individual fiefdoms with little accountability and less coordination with one another. Dr. Ashton Carter of Harvard, a former Defense Department analyst with full security clearance tasked with preparing a study of SDI for the Congressional Budget Office, concluded that the prospect for any sort of success was “so remote that it should not serve as the basis of public expectations of national policy.” Most of the press, seduced by Reagan’s own euphoria, paid little heed to such voices, instead publishing articles talking about the relative merits of laser and kinetic-energy weapons, battle stations in space, and whether the whole system should be controlled by humans or turned over to a supercomputer mastermind. With every notion as silly and improbable as every other and no direction in the form of a coherent plan from the SDI project itself, everyone could be an expert, everyone could build their own little SDI castle above the stratosphere. When journalists did raise objections, Reagan replied with more folksy homilies about how everyone thought Edison was crazy until he invented the light bulb, appealing to the good old American ingenuity that had got us to the Moon and could make anything possible. The administration’s messaging was framed so as to make objecting to SDI unpatriotic, downright un-American.

And yet even if you thought that American ingenuity would indeed save the day in the end, SDI had a more fundamental problem that made it philosophically as well as scientifically unsound. This most basic objection, cogently outlined at the time by the great astronomer, science popularizer, space advocate, and anti-SDI advocate Carl Sagan, was a fairly simple one. Even the most fanciful predictions for SDI must have a capacity ceiling, a limit beyond which the system simply couldn’t shoot down any more missiles. And it would always be vastly cheaper to build a few dozen more missiles than it would be to build and launch and monitor another battle station (or whatever) to deal with them. Not only would SDI not bring an end to nuclear weapons, it was likely to actually accelerate the nuclear-arms race, as the Soviet Union would now feel the need to not only be able to destroy the United States ten times over but be able to destroy the United States ten times over while also comprehensively overwhelming any SDI system in place. Reagan’s public characterization of SDI as a “nuclear umbrella” under which the American public might live safe and secure had no basis in reality. Even if SDI could somehow be made 99 percent effective, a figure that would make it more successful than any other defense in the history of warfare, the 1 percent of the Soviet Union’s immense arsenal that got through would still be enough to devastate many of the country’s cities and kill tens or hundreds of millions. There may have been an argument to make for SDI research aimed at developing, likely decades in the future, a system that could intercept and destroy a few rogue missiles. As a means of protection against a full-on strategic strike, though… forget it. It wasn’t going to happen. Ever. As President Nixon once said, “With 10,000 of these damn things, there is no defense.”

As with his seeming confusion about Gorbachev’s objections to SDI at their summits, it’s hard to say to what degree Reagan grasped this reality. Was he living a fantasy like so many others in the press and public when he talked of SDI rendering ICBMs “impotent and obsolete”? Whatever the answer to that question, it seems pretty clear that others inside the administration knew perfectly well that SDI couldn’t possibly protect the civilian population as a whole to any adequate degree. SDI was in reality a shell game, not an attempt to do an end-run around the doctrine of mutually assured destruction but an attempt to make sure that mutually assured destruction stayed mutually assured when it came to the United States’s side of the equation. Cold War planners had fretted for decades about a nightmare scenario in which the Soviet Union launched a first strike and the United States, due to sabotage, Soviet stealth technology, or some failure of command and control, failed to detect and respond to it in time by launching its own missiles before they were destroyed in their silos by those of the Soviets. SDI’s immediate strategic purpose was to close this supposed “window of vulnerability.” The system would be given, not the impossible task of protecting the vast nation as a whole, but the merely hugely improbable one of protecting those few areas where the missile silos were concentrated. Asked point-blank under oath whether SDI was meant to protect American populations or American missile silos, Pentagon chief of research and engineering Richard DeLauer gave a telling non-answer: “What we are trying to do is enhance deterrence. If you enhance deterrence and your deterrence is credible and holds, the people are protected.” This is of course just a reiteration of the MAD policy itself, not a separate justification for SDI. MAD just kept getting madder.

The essential absurdity of American plans for SDI seems to have struck Gorbachev by the beginning of 1987. Soviet intelligence had been scrambling for a few years by then, convinced that there had to be some important technological breakthrough behind all of the smoke the Reagan administration was throwing. It seems that at about this point they may have concluded that, no, the whole thing really was as ridiculous as it seemed. At any rate, Gorbachev decided it wasn’t worth perpetuating the Cold War over. He backed away from his demands, offering the United States the opportunity to continue working on SDI if it liked, demanding only a commitment to inform the Soviet Union and officially back out of some relevant treaties (which might very possibly have to include the 1967 Outer Space Treaty that forbade nuclear explosions in space) if it decided to actually implement it. Coupled with Gorbachev’s soaring global popularity, it was enough to start getting deals done. Reagan and Gorbachev signed their first substantial agreement, to eliminate between them 2692 missiles, in December of 1987. More would follow, accompanied by shocking liberalization and reform behind the erstwhile Iron Curtain, culminating in the night of November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall, long the tangible symbol of division between East and West, came down. Just like that, almost incomprehensible in its suddenness, the Cold War was over. Trinity stands today as a cogent commentary on that strange shadow conflict, but it proved blessedly less than prescient about the way it would end. Whatever else is still to come, there will be no nuclear war between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

If the end of the Cold War was shockingly unexpected, SDI played out exactly as you might expect. The program was renamed to the more modest Ballistic Missile Defense Organization and scaled back dramatically in 1993, by which time it had cost half again as much as the Manhattan Project — a staggering $30 billion, enough to make it the most expensive research program in history — and accomplished little. The old idea still resurfaces from time to time, but the fervor it once generated is all but forgotten now. SDI, like most of history, is now essentially a footnote.

A more inspiring closing subject is Mikhail Gorbachev. His Nobel Peace Prize notwithstanding, he strikes me as someone who hasn’t quite gotten his due yet from history. There are many reasons that the Cold War came to an end when it did. Prominent among them was the increasingly untenable Soviet economy, battered during the decade by “the Soviet Union’s Vietnam” (Gorbachev’s phrase) in Afghanistan, a global downturn in oil prices, and the sheer creaking inertia of many years of, as the old Soviet saying went, workers pretending to work while the state pretended to pay them for it. Nevertheless, I don’t agree with Marx that history is a compendium of economic forces. Many individuals across Eastern Europe stepped forward to end their countries’ totalitarian regimes — usually peacefully, sometimes violently, occasionally at the cost of their lives. But Gorbachev’s shadow overlays all the rest. Undaunted by the most bellicose Presidential rhetoric in two decades, he used politics, psychology, and logic to convince Reagan to sit down with him and talk, then worked with him to shape a better, safer world. While Reagan talked about ending MAD through his chimerical Star Wars, Gorbachev actually did it, by abandoning his predecessors’ traditional intransigence, rolling up his sleeves, and finding a way to make it work. Later, this was the man who didn’t choose to send in the tanks when the Warsaw Pact started to slip away, making him, as Victor Sebstyen put it, one of very few leaders in the history of the world to elect not to use force to maintain an empire. Finally, and although it certainly was never his intention, he brought the Soviet Union in for a soft landing, keeping the chaos to a minimum and keeping the missiles from flying. Who would have imagined Gorbachev was capable of such vision, such — and I don’t use this word lightly — heroism? Who would have imagined he could weave his way around the hardliners at home and abroad to accomplish what he did? Prior to assuming office in 1985, he was just a smart, capable Party man who knew who buttered his bread, who, as he later admitted, “licked Brezhnev’s ass” alongside his colleagues. And then when he got to the top he looked around, accepted that the system just wasn’t working, and decided to change it. Gorbachev reminds us that the hero is often not the one who picks up a gun but the one who chooses not to.

(In addition to the sources listed in the previous article, Way Out There in the Blue by Frances FitzGerald is the best history I’ve found of SDI and its politics.)