In 1983 the powers that were at Gulf and Western Industries, owners of both Paramount Pictures and Simon & Schuster, decided that it was time to bring Star Trek, a property of the former, to the computer under the stewardship of the latter. To appreciate this decision and everything that would follow it, we first should step back and briefly look at what Star Trek already meant to gamers at that time.

In late 1971, just as Star Trek was enjoying the first rush of a syndicated popularity that would soon far exceed that of its years as a first-run show, Mike Mayfield was a high-school senior with a passion for computers living near Irvine, California. He’d managed to finagle access to the University of California at Irvine’s Sigma 7 minicomputer, where he occasionally had a chance to play a port of MIT’s Spacewar!, generally acknowledged as the world’s first full-fledged videogame, on one of the university’s precious few graphical terminals. Mayfield wanted to write a space warfare game of his own, but he had no chance of securing the regular graphical-terminal access he’d need to do something along the lines of Spacewar! So he decided to try something more strategic and cerebral, something that could be displayed on a text-oriented terminal. If Spacewar! foreshadowed the frenetic dogfighting action of Star Wars many years before that movie existed, his own turn-based game would be modeled on the more stately space combat of his favorite television show. With the blissful unawareness of copyright and intellectual property that marks this early era of gaming, he simply called his game Star Trek.

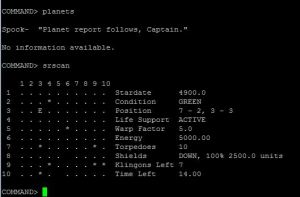

A full-on Klingon invasion is underway, the Enterprise the only Federation ship capable of stopping it. You, in the role of Captain Kirk, must try to turn back the invasion by warping from sector to sector and blowing away Klingon ships. Resource management is key. Virtually everything you do — moving within or between sectors; shooting phasers or photon torpedoes; absorbing enemy fire with your shields — consumes energy, of which you have only a limited quantity. You can repair, refuel, and restock your torpedoes at any of a number of friendly starbases scattered about the sectors, but doing so consumes precious time, of which you also have a limited quantity. If you don’t destroy all of the Klingons within thirty days they’ll break out and overrun the galaxy.

Within a year of starting on the game Mayfield moved on from the Sigma 7 to a much slicker HP-2100 series machine to which he had managed to convince the folks at his local Hewlett-Packard branch to give him access. He quickly ported Star Trek to HP Time-Shared BASIC, in which form, along with so many other historically important games, it spread across the country. It was discovered by David Ahl, who would soon go on to found the immensely important magazine Creative Computing. Ahl published an expanded version of the game, Super Star Trek, in 1974 as a type-in listing in one of Creative Computing‘s earliest issues. In 1977, Byte published another version, one of the few game listings ever to appear in the pages of that normally staunchly tech-oriented magazine. In 1978, Ahl republished his Super Star Trek in his book BASIC Computer Games. This collection of old standards largely drawn from the HP Time-Shared BASIC computing culture arrived at a precipitous time, just as the first wave of pre-assembled PCs were appearing in stores and catalogs. Super Star Trek was the standout entry in BASIC Computer Games, by far the longest program listing as well as the most complex, replayable, and interesting game to be found within its pages.

On the strength of this, the first million-selling computer book in history, Star Trek spread even more widely and wildly across the little machines than it had the big ones. From here the history of Star Trek the computer game gets truly bewildering, with hundreds of variants on Mayfield’s basic template running on dozens of systems. Some added to the invading Klingon hordes Star Trek‘s other all-purpose villains the Romulans, complete with their trademark cloaking devices; some added graphics and/or sound; some added the personalities of Spock, McCoy, Scott, and the rest reporting developments in-character. And the variations continually one-upped one another with ever more elaborate weapon and damage modeling. In 1983 a small company who called themselves Cygnus (later renamed to Interstel) reworked and expanded the concept into a commercial game called Star Fleet I: The War Begins! to considerable success. In this version the serial numbers were to some extent filed off for obvious reasons, but Cygnus didn’t really make the most concerted of efforts to hide their game’s origins. Klingons, for instance, simply became “Krellans,” while their more creatively named allies the “Zaldrons” have, you guessed it, cloaking devices.

This, then, was the situation when Simon & Schuster secured a mandate in 1983 to get into home computers, and to bring Star Trek along for the ride. Star Trek in general was now a hugely revitalized property in comparison to the bunch of orphaned old syndicated reruns that Mayfield had known back in 1971. There were now two successful films to the franchise’s credit and a third well into production, as well as a new line of paperback novels on Simon & Schuster’s own Pocket Books imprint regularly cracking bestseller lists. There was a popular new stand-up arcade game, Star Trek: Strategic Operations Simulator. And there was a successful tactical board game of spaceship combat, and an even more successful full-fledged tabletop RPG. There was even a space shuttle — albeit one which would never actually fly into space — sporting the name Enterprise. And of course Star Trek was all over computers in the form of ports of Strategic Operations Simulator as well as, and more importantly, Mike Mayfield’s unlicensed namesake game and its many variants, of which Paramount was actually quite remarkably tolerant. To my knowledge no one was ever sued over one of these games, and when David Ahl had asked for permission to include Super Star Trek in BASIC Computer Games Paramount had cheerfully agreed without asking for anything other than some legal fine print at the bottom of the page. Still, it’s not hard to understand why Paramount felt it was time for an official born-on-a-home-computer Star Trek game. Even leaving aside the obvious financial incentives, both Strategic Operations Simulator and Mayfield’s Star Trek and all of its successors were in a sense very un-Star Trek sorts of Star Trek games. They offered no exploring of strange new worlds, no seeking out of new life and new civilizations. No, these were straight-up war games, exactly the scenario that Star Trek‘s television writers had had to be careful not to let the series devolve into. Those writers had often discussed the fact that if any of the Enterprise‘s occasional run-ins with the Romulans or the Klingons ever resulted in open, generalized hostilities, Star Trek as a whole would have to become a very different sort of show, a tale of war in space rather than a five-year mission of peaceful (for the most part) exploration. Star Trek the television show would have had to become, in other words, like Star Trek the computer game.

But now, at last, Simon & Schuster had the mandate to move in the other direction, to create a game more consonant with what the show had been. In that spirit they secured the services of Diane Duane, an up-and-coming science-fiction and fantasy writer who had two Star Trek novels already in Pocket’s publication pipeline, to write a script for a Star Trek adventure game. Duane began making notes for an idea that riffed on the supposedly no-win Kobayashi Maru training scenario that had been memorably introduced at the beginning of the movie Star Trek II. The game’s fiction would have you participating in an alternative, hopefully more winnable test being considered as a replacement. Thus you would literally be playing The Kobayashi Alternative, the goal of which would be to find Mr. Sulu (Star Trek: The Search for Sulu?), now elevated to command of the USS Heinlein, who has disappeared along with his ship in a relatively unexplored sector of the galaxy.

Simon & Schuster’s first choice to implement this idea was the current darling of the industry, Infocom. As we’ve already learned in another article, Simon & Schuster spent a year earnestly trying to buy Infocom outright beginning in late 1983, dangling before their board the chance to work with a list of properties headed by Star Trek. An Infocom-helmed Star Trek adventure, written by Diane Duane, is today tempting ground indeed for dreams and speculation. However, that’s all it would become. Al Vezza and the rest of Infocom’s management stalled and dithered and ultimately rejected the Simon & Schuster bid for fear of losing creative control and, most significantly, because Simon & Schuster was utterly disinterested in Infocom’s aspirations to become a major developer of business software. As Infocom continued to drag their feet, Simon & Schuster made the fateful decision to take more direct control of Duane’s adventure game, publishing it under their own new “Computer Software Division” imprint.

Development of The Kobayashi Alternative was turned over to a new company called Micromosaics, founded by a veteran of the Children’s Television Workshop named Lary Rosenblatt to be a sort of full-service experience architect for the home-computer revolution, developing not only software but also the packaging, the manuals, and sometimes even the advertising that accompanied it; their staff included at least as many graphic designers as programmers. The packaging they came up with for The Kobayashi Alternative was indeed a stand-out even in this era of oft-grandiose packaging. Its centerpiece was a glossy full-color faux-Star Fleet briefing manual full of background information about the Enterprise and its crew and enough original art to set any Trekkie’s heart aflutter (one of these pictures, the first in this article, I cheerfully stole out of, er, a selfless conviction that it deserves to be seen). Sadly, the packaging also promised light years more than the actual contents of the disk delivered.

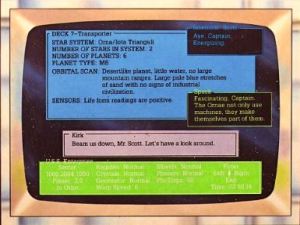

This alleged screenshot from the back of The Kobayashi Alternative‘s box is one of the most blatant instances of false advertising of 1980s gaming.

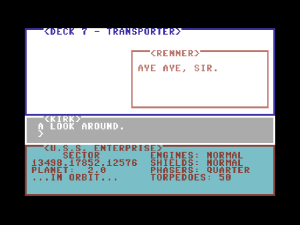

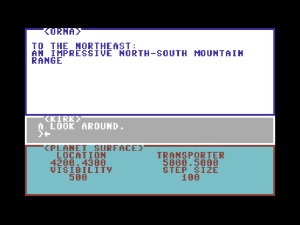

Whatever else you can say about it, you can’t say that The Kobayashi Alternative played it safe. Easily dismissed at a glance as just another text adventure, it’s actually a bizarrely original mutant creation, not quite like any other game I’ve ever seen. Everything that you as Captain Kirk can actually do yourself — “give,” “take,” “use,” “shoot,” etc. — you accomplish not through the parser but by tapping function-key combinations. You move about the Enterprise or planetside using the arrow keys. The parser, meanwhile, is literally your mouth; those things you type are things that you say aloud. This being Star Trek and you being Captain Kirk, that generally means orders that you issue to the rest of your familiar crew. And then, not satisfied with giving you just an adventure game with a very odd interface, Micromosaics also tried to build in a full simulation of the Enterprise for you to logistically manage and command in combat. Oh, and the whole thing is running in real time. If ever a game justified use of the “reach exceeded its grasp” reviewer’s cliché, it’s this one. The Kobayashi Alternative is unplayable. No one at Micromosaics had any real practical experience making computer games, and it shows.

The Kobayashi Alternative is yet another contender for the title of emptiest adventure game ever. In fact, it takes that crown handily from the likes of Level 9’s Snowball and Electronic Arts’s Amnesia. In lieu of discrete, unique locations, each of the ten planets you can beam down to consists of a vast X-Y grid of numerical coordinates to dully trudge across looking for the two or three places that actually contain something of interest. Sometimes you get clues in the form of coordinates to visit, but at other times the game seems to expect you to just lawnmower through hundreds of locations until you find something. The Enterprise, all 23 decks of it, is implemented in a similar lack of detail. It turns out that all those empty, anonymous corridors we were always seeing in the television show really were almost all there was to the ship. When you do find something or somebody, the parser is so limited that you never have any confidence in the conversations that result. Some versions of the game, for instance, don’t even understand the word “Sulu,” making the most natural question to ask anyone you meet — “Where is Sulu?” — a nonstarter. And then there are the bugs. Crewmen — but not you — can beam down to poisonous planets in their shirt sleeves and remain unharmed; when walking east on planets the program fails to warn you about dangerous terrain ahead, meaning you can tumble into a lake of liquid nitrogen without ever being told about it; crewmen inexplicably root themselves to the ground planetside, refusing to follow you no matter how you push or cajole or even start shooting at them with your phaser.

Following The Kobayashi Alternative‘s 1985 release, gamers, downright desperate as they were to play in this beloved universe, proved remarkably patient, while Simon & Schuster also seemed admirably determined to stay the course. Some six months after the initial release they published a revised version that, they claimed, fixed all of the bugs. The other, more deep-rooted design problems they tried to ret-con with a revised manual, which rather passive-aggressively announced that “The Kobayashi Alternative differs in several important ways from other interactive text simulations that you may have used,” including being “completely open-ended.” (Don’t cry to us if this doesn’t play like one of Infocom’s!) The parser problems were neatly sidestepped by printing every single phrase the parser could understand in the manual. And the most obvious major design flaw was similarly addressed by simply printing a list of all the important coordinates on all of the planets in the manual.

Interest in the game remained so high that Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia, one of the premier fan voices in adventure gaming, printed a second multi-page review of the revised version to join her original, a level of commitment I don’t believe she ever showed to any other game. Alas, even after giving it the benefit of every doubt she couldn’t say the second version was any better than the original. It was actually worse: in fixing some bugs, Micromosaics introduced many others, including one that stole critical items silently from your inventory and made the game as unsolvable as the no-win scenario that provided its name. Micromosaics and Simon & Schuster couldn’t seem to get anything right; even some of the planet coordinates printed in the revised manual were wrong, sending you beaming down into the middle of a helium sea. Thus Scorpia’s second review was, like the first, largely a list of deadly bugs and ways to work around them. The whole sad chronicle adds up to the most hideously botched major adventure-game release of the 1980s, a betrayal of consumer trust worthy of a lawsuit. This software thing wasn’t turning out to be quite as easy as Simon & Schuster had thought it would be.

While The Kobayashi Alternative stands today as perhaps the most interesting of Simon & Schuster’s Star Trek games thanks to its soaring ambitions and how comprehensively it fails to achieve any of them, it was far from the last of its line. Understandably disenchanted with Micromosaics but determined to keep plugging away at Star Trek gaming, Simon & Schuster turned to another new company to create their second Star Trek adventure: TRANS Fiction Systems.

The story of TRANS Fiction begins with Ron Martinez, who had previously written a couple of Choose Your Own Adventure-style children’s gamebooks for publisher Byron Preiss, then had written the script for Telarium’s computerized adaptation of Rendezvous with Rama. Uninspiring as the finished result of that project was, it awakened a passion to dive deeper and do more with interactive fiction than Telarium’s limited technology would allow. Martinez:

If this was really an art form — like film, for example — you’d really want to know how to create the entire work. In film, you’d want to understand how to work a camera, how to shoot, how to edit, how to really make the finished product. For me, as a writer, I understood that I had to know how to program.

Like just about everybody else, I worshiped the Infocom work, was just amazed by it. So, my goal was to do two things simultaneously:

1. Learn how to program, so that I could —

2. Build an interactive-fiction system that was as good or better than Infocom’s.

Working with a more experienced programmer named Bill Herdle, Martinez did indeed devise his own interactive-fiction development system using a programming language we seem to be meeting an awful lot lately: Forth. Martinez, Herdle, and Jim Gasperini, another writerly alum of Byron Preiss, founded TRANS Fiction to deploy their system. They sincerely believed in interactive fiction as an art form, and were arrogant enough to believe themselves unusually qualified to realize its potential.

We started as writers and then learned the programming. Of other companies, we used to say that the people who built the stage are writing the plays. We used to look down our nose at people who were technical but had no sense of what story was all about attempting to use this medium which we thought would redefine fiction — we really believed that. Instead of having people who were technical trying to write stories, we thought it really had to come the other way, so the technology is in the service of the story and the characters and the richness of the world.

Thanks to their connections in the world of book publishing and their New York City location, TRANS Fiction was soon able to secure a contract to do the next Simon & Schuster Star Trek game. It wasn’t perhaps a dream project for a group of people with their artistic aspirations, but they needed to pay the bills. Thus, instead of things like the interactive version of William Burroughs’s novel Nova Express that Martinez fruitlessly pursued with Electronic Arts, TRANS Fiction did lots of work with less rarefied properties, like the Make Your Own Murder Party generator they did for EA and, yes, Star Trek.

I can tell you that it wasn’t with great joy that we were working with these properties. There’s something soulless about working with a big property owned by a conglomerate. Even though we might love Spock, it was still a property, and there were brand police, who had to review everything that Spock might say or do. We would extend the world and try to introduce new aspects of the history of these characters, but they’d have to sign off on it.

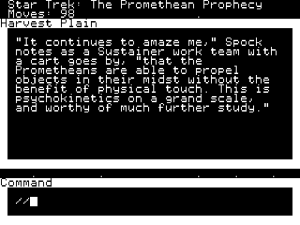

Given Martinez’s attitude as well as that set of restrictions, it’s not terribly shocking that TRANS Fiction’s first Star Trek game, The Promethean Prophecy, is not all that terribly inspired or inspiring. Nor is its parser or game engine quite “as good as,” much less “better than,” Infocom’s. A much more conventional — perhaps too conventional — text adventure than its crazy predecessor, its status as the most enjoyable of all the Simon & Schuster-era Treks has more to do with the weaknesses of its peers than its own intrinsic strengths.

The Promethean Prophecy doesn’t try to be a starship simulator to anywhere near the same degree as its predecessor. While it does open with a space battle, said battle is largely an exercise in puzzle solving, in figuring out the next command that will drive the hard-wired plot forward and not get you killed, rather than a real tactical simulation. After that sequence, you beam down to Prometheus, the only planet in the game, and start on a fairly standard “figure out this alien culture” puzzle-driven text adventure which, other than having Kirk, Spock, and company as its stars, doesn’t feel all that notably Star Trek-like at all. What with its linear and heavily plotted opening followed by a non-linear body to be explored at your own pace, it reminds me more than anything of Infocom’s Starcross. This impression even extends to the puzzles themselves, which like those of Starcross often involve exchanging items with and otherwise manipulating the strange aliens you meet. And yet again like in Starcross, there is no possibility of having real conversations with them. Unfortunately, coming as it did four years after Starcross, The Promethean Prophecy is neither as notable in the context of history nor quite as clever and memorable on its own terms as a game. From its parser to its writing to its puzzles it’s best described as “competent” — a description which admittedly puts it head and shoulders above many of Infocom’s competitors and its own predecessor. The best of this era of Star Trek games, it’s also the one that feels the least like Star Trek.

Still, The Promethean Prophecy did have the virtue of being relatively bug free, a virtue that speaks more to the diligence of TRANS Fiction than Simon & Schuster; as Martinez later put it, “Nobody at Simon & Schuster really understood how we were doing any of it.” It was greeted with cautiously positive reviews and presumably sold a reasonable number of copies on the strength of the Star Trek name alone, but it hardly set the industry on fire. An all-text game of any stripe was becoming quite a hard sell indeed by the time of its late 1986 release.

After The Promethean Prophecy Simon & Schuster continued to doggedly release new Star Trek games, a motley assortment that ranged from problematic to downright bad. For 1987’s The Rebel Universe, they enlisted the services of our old friend Mike Singleton, who, departing even more from The Promethean Prophecy than that game had from its predecessor, tried to create a grand strategy game, a sort of Lords of Midnight in space. It was full of interesting ideas, but rushed to release in an incomplete and fatally unbalanced state. For 1988’s First Contact (no relation to the 1996 movie), they — incredibly — went back to Micromosaics, who simplified and retrofitted onto the old Kobayashi Alternative engine the ability to display the occasional interstitial graphic. Unfortunately, they also overcompensated for the overwhelming universe of their first game by making First Contact far too trivial. The following year’s adaptation of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, oddly released through Mindscape rather than using Simon & Schuster’s own imprint, and 1990’s The Transinium Challenge, another product of TRANS Fiction and the first game to feature the cast of The Next Generation, were little more than interactive slide shows most notable for their heavy use of digitized images from the actual shows at a time when seeing real photographs of reasonable fidelity on a computer screen was still a fairly amazing thing.

It was all disappointing enough that by the beginning of the 1990s fans had begun to mumble about a Star Trek gaming curse. And indeed, it’s hard to know what to make of the handling of the franchise during this period. Gifted with easily one of the five most beloved properties on the planet amongst the computer-gaming demographic, Simon & Schuster refused to either turn it over to an experienced software publisher who would know what to do with it — virtually any of them would have paid a hell of a lot of money to have a crack at it — or to get really serious and pay a top-flight developer to create a really top-flight game. Instead they took the pointless middle route, tossing off a stream of rushed efforts from second-tier developers that managed to be unappealing enough to be sales disappointments despite the huge popularity of the name on their boxes, while other games made without a license — notably Starflight — proved much more successful at evoking the sense of wonder that always characterized Star Trek at its best. It wouldn’t be until 1992 that Star Trek would finally come to computers in a satisfying form that actually felt like Star Trek — but that’s a story for another day.

For today, I encourage you to have a look at one or more of the variants of Mike Mayfield’s original Star Trek game. There are a number of very good versions that you can play right in your browser. One of the first really compelling strategy games to appear on computers and, when taking into account all of its versions and variations, very likely the single most popular game on PCs during that Paleolithic era of about 1978 to 1981, it’s still capable of stealing a few hours of your time today. It’s also, needless to say, far more compelling than any commercial Star Trek released prior to 1992. Still, completionism demands that I also make available The Kobayashi Alternative and The Promethean Prophecy in their Commodore 64 incarnations for those of you who want to give them a go as well. They aren’t the worst adventures in the world… no, I take that back. The Kobayashi Alternative kind of is. Maybe it’s worth a look for that reason alone.

(The history of Mike Mayfield’s Star Trek has been covered much more thoroughly than I have here by other modern digital historians. See, for instance, Games of Fame and Pete Turnbull’s page on the game among many others. Most of my information on Simon & Schuster and TRANS Fiction was drawn from Jason Scott’s interview with Martinez for Get Lamp; thanks again for sharing, Jason! Scorpia’s review and re-review of The Kobayashi Alternative appeared in Computer Gaming World‘s March 1986 and August 1986 issues respectively.

For an excellent perspective on how Star Trek‘s writers saw the show as well as the state of Star Trek around the time that Mayfield first wrote his game, see David Gerrold’s The World of Star Trek. Apart from its value as a research source, it’s also a very special book to me, the first real work of criticism that I ever read as a kid. It taught me that you could love something while still acknowledging and even dissecting its flaws. I’m not as enchanted with Star Trek now as I was at the Science Fiction Golden Age of twelve, but Gerrold’s book has stuck with me to become an influence on the work I do here today. I was really happy recently to see it come back into “print” as an e-book.)